Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations and editions used

- Introduction: a life, in fragments

- Chapter 1 Autonomy, authority, and representing the past under the Principate

- Chapter 2 Agricola and the crisis of representation

- Chapter 3 The burdens of Histories

- Chapter 4 “Elsewhere than Rome”

- Chapter 5 Tacitus and Cremutius

- Conclusion: on knowing Tacitus

- Works cited

- Index of passages discussed

- General index

- References

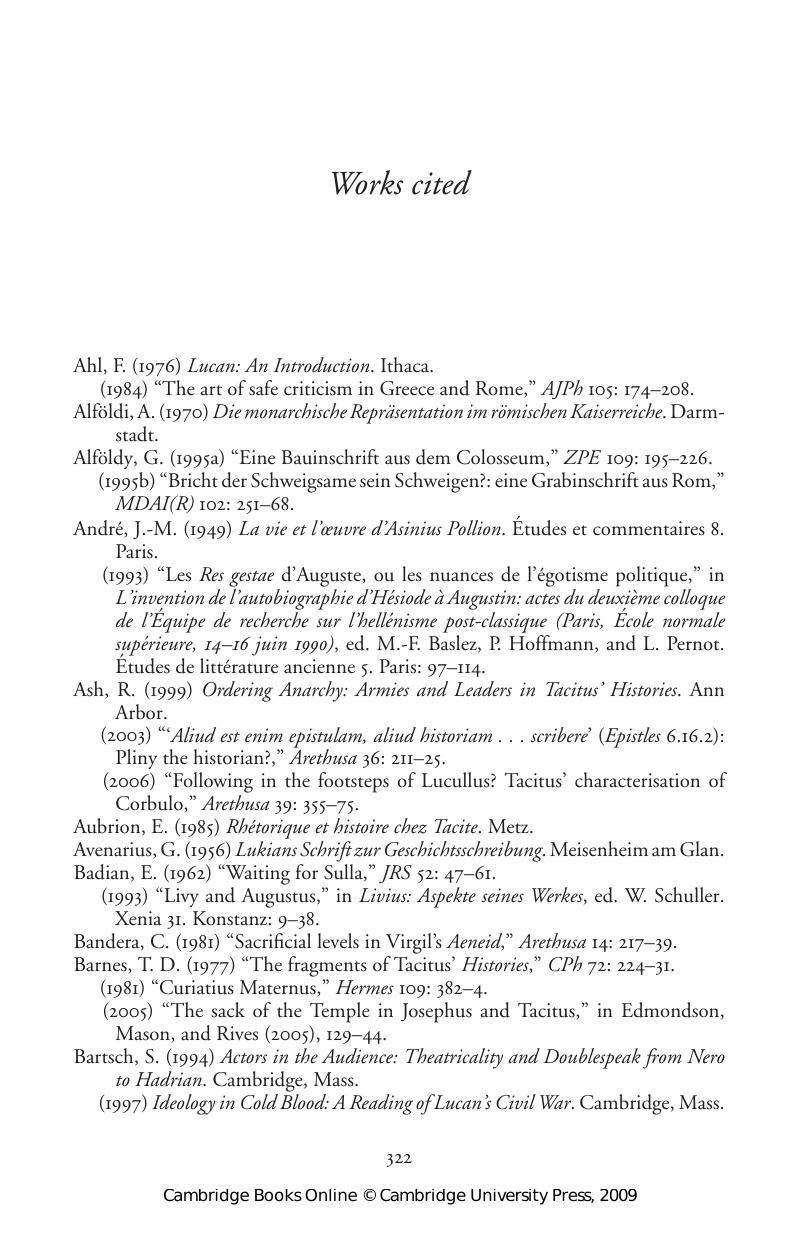

Works cited

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 September 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations and editions used

- Introduction: a life, in fragments

- Chapter 1 Autonomy, authority, and representing the past under the Principate

- Chapter 2 Agricola and the crisis of representation

- Chapter 3 The burdens of Histories

- Chapter 4 “Elsewhere than Rome”

- Chapter 5 Tacitus and Cremutius

- Conclusion: on knowing Tacitus

- Works cited

- Index of passages discussed

- General index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Writing and Empire in Tacitus , pp. 322 - 343Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2008