Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: ‘What we have lost is all the more reason for cherishing what survives’

- 1 Quod severis metes: Birth of the United Nations

- Chapter 2 South African Indians

- 3 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- 4 International covenants on human rights

- 5 United Nations surveys of human rights issues

- 6 Evolution of human rights at the United Nations

- 7 State sovereignty at issue

- 8 Apartheid on the agenda

- 9 Shadow of Sharpeville

- 10 General relations with the United Nations

- 11 Concluding observations

- Appendix: Selected provisions of the United Nations Charter

- Sources and references

- Index

11 - Concluding observations

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 March 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: ‘What we have lost is all the more reason for cherishing what survives’

- 1 Quod severis metes: Birth of the United Nations

- Chapter 2 South African Indians

- 3 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- 4 International covenants on human rights

- 5 United Nations surveys of human rights issues

- 6 Evolution of human rights at the United Nations

- 7 State sovereignty at issue

- 8 Apartheid on the agenda

- 9 Shadow of Sharpeville

- 10 General relations with the United Nations

- 11 Concluding observations

- Appendix: Selected provisions of the United Nations Charter

- Sources and references

- Index

Summary

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to extract major elements of SA's early relations with the UN as they have emerged from an examination of available documentation and themes addressed in previous chapters and, somewhat cursorily, to consider their relevance, if any, to later developments. To do so it will be necessary to refer to events outside the time frame of this work. Some overlapping with earlier chapters is thus unavoidable.

South Africa and interpretation of the Charter

‘History,’ observed F. Fernandez-Armesto, ‘is moulded more by the falsehood men believe than by the facts that can be verified.’ The remark serves as a counterpoint to Kelsen's prefatorial comment: ‘It is not the logically “true”, it is the politically preferable meaning of the interpreted norm which becomes binding.’ Against this background, the concept of the ‘amendment of the Charter by interpretation’ against which SA representatives so often inveighed, tends to lose practical relevance. No document survives the test of time untouched; words change their sense with the passage of the years. Several of those used in the Charter were already open to various interpretations when they were first included. Most drafters had specific meanings in mind, but even they recognised that their brainchild would have to adapt to a changing world if it and the UN were to last. As G. Ress has pointed out, the fact that the text has survived for 50 years with minimal changes proves its adaptability. The declaratory resolutions attendant on the admission of the newly independent states at the end of the 1950s did not indicate their rejection of certain Charter provisions as at first drafted, but rather their desire to relate them to conditions with which they were familiar, with, for the most part, the assent of the original members.

Kelsen's rider that the choice of interpretation ‘as a legal act’ depended on political motives begged the fact that the UN is not a law-making body. It can purport to codify existing international law, and to adopt conventions or declaratory recommendations, but the effectiveness of its actions is limited to the members who choose to abide by them. Thus, despite its moral significance, the UDHR, like the resolutions which flowed from the UNCORS reports, was a political rather than a juridical document, the legal force of the international instruments it spawned binding only the states that ratified them.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

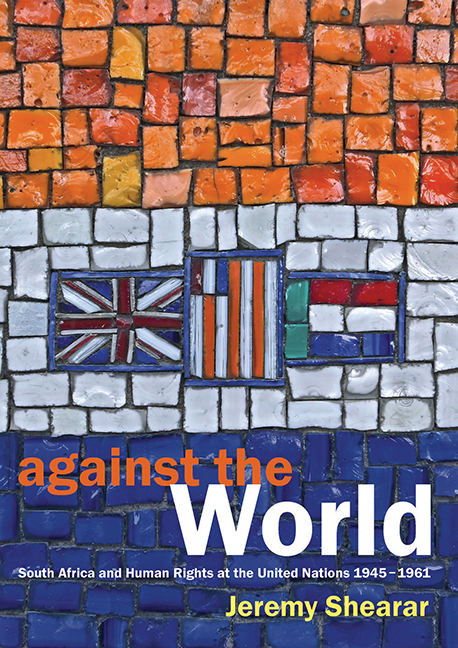

- Against the WorldSouth Africa and Human Rights at the United Nations 1945–1961, pp. 236 - 259Publisher: University of South AfricaPrint publication year: 2017