Book contents

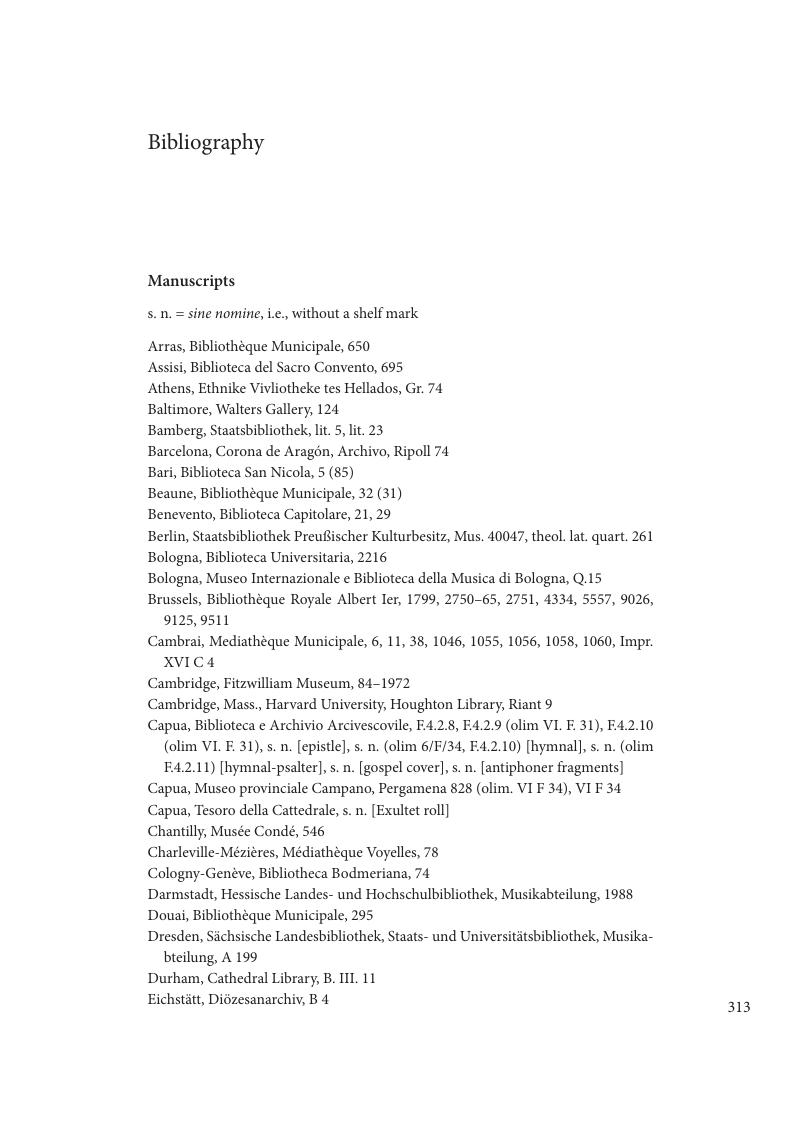

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 November 2016

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Music and Culture in the Middle Ages and BeyondLiturgy, Sources, Symbolism, pp. 313 - 350Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2016