Book contents

- Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860–1960

- Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860–1960

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Romanization and Characters

- Introduction

- 1 A Chinese Language

- 2 Unchangeable Roots

- 3 The Science of Language in Republican China

- 4 The People’s Language

- 5 The Mandarin Revolution

- Epilogue

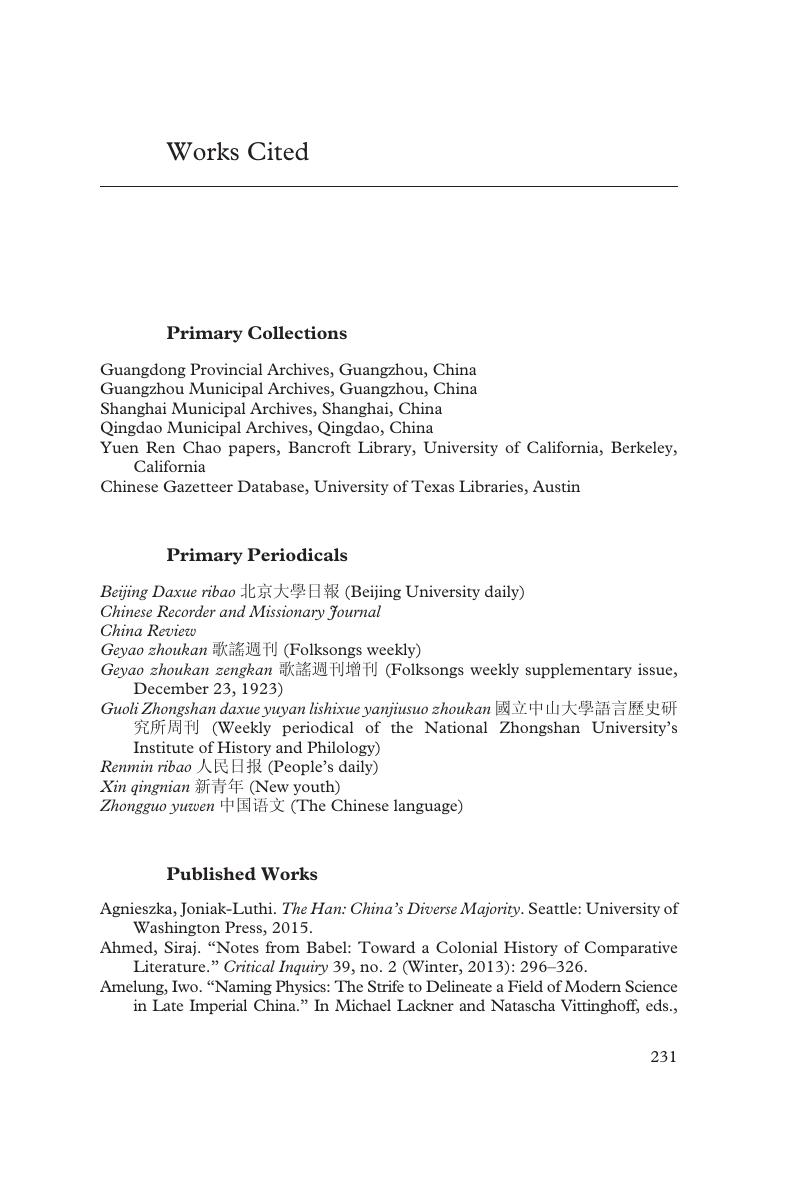

- Works Cited

- Index

- References

Works Cited

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 February 2020

- Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860–1960

- Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860–1960

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Romanization and Characters

- Introduction

- 1 A Chinese Language

- 2 Unchangeable Roots

- 3 The Science of Language in Republican China

- 4 The People’s Language

- 5 The Mandarin Revolution

- Epilogue

- Works Cited

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Dialect and Nationalism in China, 1860–1960 , pp. 231 - 255Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020