Book contents

- Early Latin

- Early Latin

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction: What Is ‘Early Latin’?

- Part I The Epigraphic Material

- Part II Drama

- Part III Other Genres and Fragmentary Authors

- Part IV Reception

- Bibliography

- Index Verborum

- Index of Non-Latin Words

- Index Locorum Potiorum

- Subject Index

- References

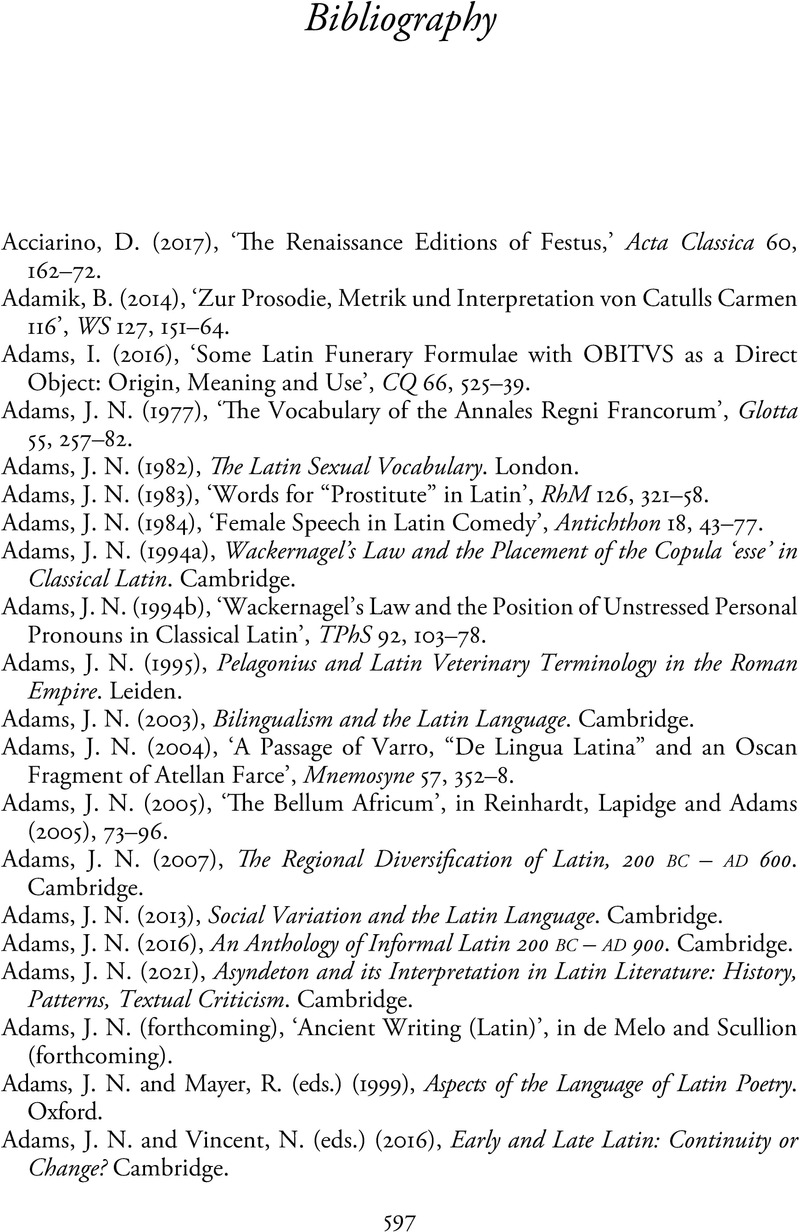

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 July 2023

- Early Latin

- Early Latin

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction: What Is ‘Early Latin’?

- Part I The Epigraphic Material

- Part II Drama

- Part III Other Genres and Fragmentary Authors

- Part IV Reception

- Bibliography

- Index Verborum

- Index of Non-Latin Words

- Index Locorum Potiorum

- Subject Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Early LatinConstructs, Diversity, Reception, pp. 597 - 637Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023