Overview

Chapter 1 argued that the way in which bodies and body parts have been obtained for medical research and teaching creates three core forms of dispute. These have incrementally (and sometimes sharply, as for instance with the NHS Alder Hey organ retention controversy) shaped public understandings of the ethics and practices of medical science and thus the possibilities of, and constraints on, medical research. This chapter analyses the first of our categories: the implicit dispute. An implicit dispute is what happens when a person dies, their body enters a medical research and teaching culture, but informed consent is implied, never documented in full for the bereaved. A lot is therefore left unsaid, and deliberately so. It is normal for these sorts of bureaucratic processes to be very light touch, and to have audit procedures that look robust, but are the opposite. The aim being to make it a difficult logistical task to track at the time, or retrace later, exactly what is happening, or has happened, to human material once it enters a system of body supply. Even an insider might not know who exactly had shared a body and body parts, and what scientific studies these relate to. Those grieving thus never got an opportunity to make an informed choice. They are given the impression at the time of a loved one’s death that informed consent existed, when it did not. Instead, it was often implied, particularly by those staffing large teaching hospitals. In modern Britain, a proper system of consent was an aspiration, not a uniform working practice. As we shall see, implicit disputes thus constituted what modern research scientists would term ‘bio-commons’, and reconstructing their human stories is the central focus of this fourth chapter.

There are many ways in which such disputes can be analysed, but in this chapter we focus (detailing the 1950s and 1960s in particular) on disputes over bodies that became available because of bad weather. A first section explores the connection between foggy weather patterns, the deaths of the poorest members of society and the consequent supply of bodies and body parts for medical research and teaching.1 While everyone may have disliked fog, it was a boon for a medical community needing more research material.2 The chapter then moves on to develop this theme across a number of sections, focussing on the case study of a young boy who died in the ‘Great Fog’ of 1952 and was dissected for teaching and research purposes. Remapping the material journey of his brief life-story and body reveals the extra time of the dead created by the actor network of hospital staff, anatomists, coroners, and scientists. Subsequently, the chapter generalises this individual experience, reconstructing the body supply network for St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London from 1930 (when the New Poor Law ended) until 1965 (when a ‘mechanism of body donation’ was put in place that other medical schools in the capital subsequently copied). The next step in this critical analysis is to expand upon the new data, focussing on a number of representative stories of those taken for dissection and who did not consent to the ‘donation’ process. They ended up being dissected by virtue of being alone, friendless, socially isolated, or they died inside NHS premises where medical research was a priority. The penultimate section compares St Bartholomew’s data to national statistics on ‘body donation’ figures for the whole of England during the 1990s, arguing amongst other things that women come to be the mainstay of the body bequest process, and that current practices for encouraging organ and body donation do not reflect that material fact. The final section thus asks how the implicit disputes that arise out of the covert (if at the time perfectly legal) supply of bodies and body parts for medical research and teaching have shaped trust in medicine and the development of professional boundaries, a theme taken up again at length in Chapter 5. In this way, this fourth chapter builds on some of the core themes of this book, as outlined in Chapter 1, including: notions of expertise, the ambiguities of consent, the rise of the information state, deferential power relations and the particular authority of individual actors in the wider medical science and research community. We begin our engagement with these themes by exploring the medical hazard of fog; in a hidden history of disputed bodies, few could escape the old English weather lore –

Fog – Weather Warning!

In December 1952, The Times newspaper featured a severe weather warning about the harmful effects of a deepening winter fog across the capital:

A ‘LONDON PARTICULAR’

Of all the afflictions which visit the inhabitants of this temperate climate, fog is the most exasperating. There are some who think well of frost or snow, and rain is an undoubted necessity. It refreshes the earth and the air, and at one time was the only decent scavenging system London knew. But there is no decent use for fog. It cripples business and brings even winter sports to a standstill. Fog is a dirty and stifling cloud without any silver lining at all. We could do well without fog. … Fog is altogether too big a job for Science to handle.3

By the 1950s, air-pollution trapped in fog attracted considerable column inches in the British medical press.4 Smog from the constant burning of coal fires in houses, shops and factories across the capital was blighting Britain’s major cityscapes. Newspapers described the daily distress of commuting under a ‘green-yellow miasma’ lingering on London’s streets.5 The toxic haze eventually led to a concerted public health campaign around the time of this ‘Great Fog’, known as the ‘pea-souper’, of 1952.6 Scientists could not, as The Times observed, disperse fog, but it had boons for medical research and teaching. Weather crises such as that in 1952 increased emergency admissions to hospitals and more people died of heart and lung complaints, prompting a synchronicity of greater body supply on the one hand and calls for better medical research on the other hand. Moreover, there was also a deeper history.7 Trading dead bodies in fog, moving them under the cover of darkness, buying and selling at the back of Poor Law infirmaries and workhouses or on the streets of London had been commonplace for centuries. After the NHS was created in 1948, the old welfare institutions of the New Poor Law had become County Council care-homes, and they continued their supply-lines. Still the anatomical sciences waited in wintertime for the Grim Reaper to stalk British cities in the fog. Yet seldom did the scientific community speak openly about this fact of life because of public sensitivities surrounding dissection.

There is no doubt that the dense smog that hung over London at the start of December 1952 was an exceptional weather event, even for the damp British climate. A low, dank cloud covered the capital. It sat stubbornly on top of impenetrable smoke pollution. Out-of-doors everywhere was wet with a cold miasma. Foggy rain dripped from trees and formed a drizzly haze under lampposts. Along the packed streets, passers-by coughed, spluttered and wheezed, to and from work. The Times ran a daily health feature on how to combat colds, sneezes and asthma. They did so because of widespread concern about the high number of extra emergency admissions to large teaching hospitals that had stretched medical services to almost their breaking point. In North West London, Times journalists reported on how Harrow public school pupils experienced a cacophony of illness even though they lived on top of a steep hill, 406 feet above the rest of the capital. Most had contracted sore throats, chest cackles, and high temperatures. Cancelling sports in the foggy conditions meant that everyone stayed indoors in their boarding houses to manage the spread of infection. Tragically, however, the Headmaster of Harrow, Dr R. W. Moore, died aged just 46 during the foggy pall of 1952. His obituary explained that ‘early in 1951 he had an attack of bronchial pneumonia’ and despite being X-rayed and operated on to alleviate his condition, the symptoms returned with renewed vigour in the winter fog of 1952.8 All the pupils at Harrow ‘underwent X-ray examination’, but Moore died of the latest outbreak. The Times health correspondent highlighted that many London residents were experiencing the same severe symptoms of bronchial pneumonia. It was the worst outbreak since ‘the influenza pandemic of 1918’. Civil servants at the Ministry of Health meantime emphasised the virulence of the 1952 pneumonia strain. They warned central government that the peak in mortality rates from fatal lung diseases was akin to the sort of death statistics of ‘the last great cholera epidemic of 1866’.9 A public health report was thus urgently prepared for the London County Council. It revealed that some ‘2,484’ residents in the capital died from a ‘tenfold increase in bronchitis’ in the reporting period from 5 November to 5 December 1952.10 Within days, however, the foggy conditions worsened. Medical science was on hand to treat patients but also to benefit from higher fatalities in its dissection spaces.

During early to mid-December 1952, all of the daily newspapers devoted their front pages to the deepening winter fog that descended over London and would not shift.11 A combination of high pressure, near-freezing temperatures, light winds and thickening smog had intensified the hazardous public health crisis. The Automobile Association told The Times on 8 December 1952 that ‘it is the worst fog they had ever known’. The Daily Telegraph reported on how the dense smog had ‘blacked out central London and a band 40 miles across. … All buses had stopped by 10 p.m. Hundreds of cars were abandoned. … Thousands of people did not get milk.’12 Nightly there was a shutdown of all the capital’s transport systems because bus and train drivers could not see more than 100 yards ahead on the roads or railway networks. Only the underground stayed open, but even underneath London the fog seeped into the drainage system tunnels. Airport traffic-control staff took the unprecedented decision to divert ‘500 planes’ from London Heathrow to Hurn aerodrome in Bournemouth. Few planes could land safely in the capital because they did not have the radar capabilities to guide them blind onto the ground. The ambulance service faced a crisis it could not cope with as well: ‘It took five or six times as long as usual to get cases to hospital’, according to the Daily Telegraph; so bad was it that: ‘… women gave birth to babies in fog-bound ambulances’. Yet, it was the rising daily death toll, disproportionate amongst children and their grandparents, which caused the greatest public concern. In two weeks, ‘some 4,000 died’. The death toll then rose to ‘10,000’ in total by the close of the Christmas holidays of 1952.13 A single case-history from this tragic period – a young boy aged 7 living in the Harrow area and dying in December 1952 – symbolises the central themes of this chapter because we can trace what happened next to his human remains. Out of the medical miasma of fog emerges the material journey, reconstructed from detailed record linkage work on the mechanisms of body donation.

TAB – A Hidden History Remapped

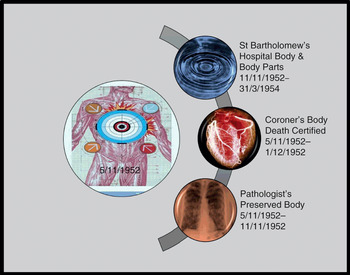

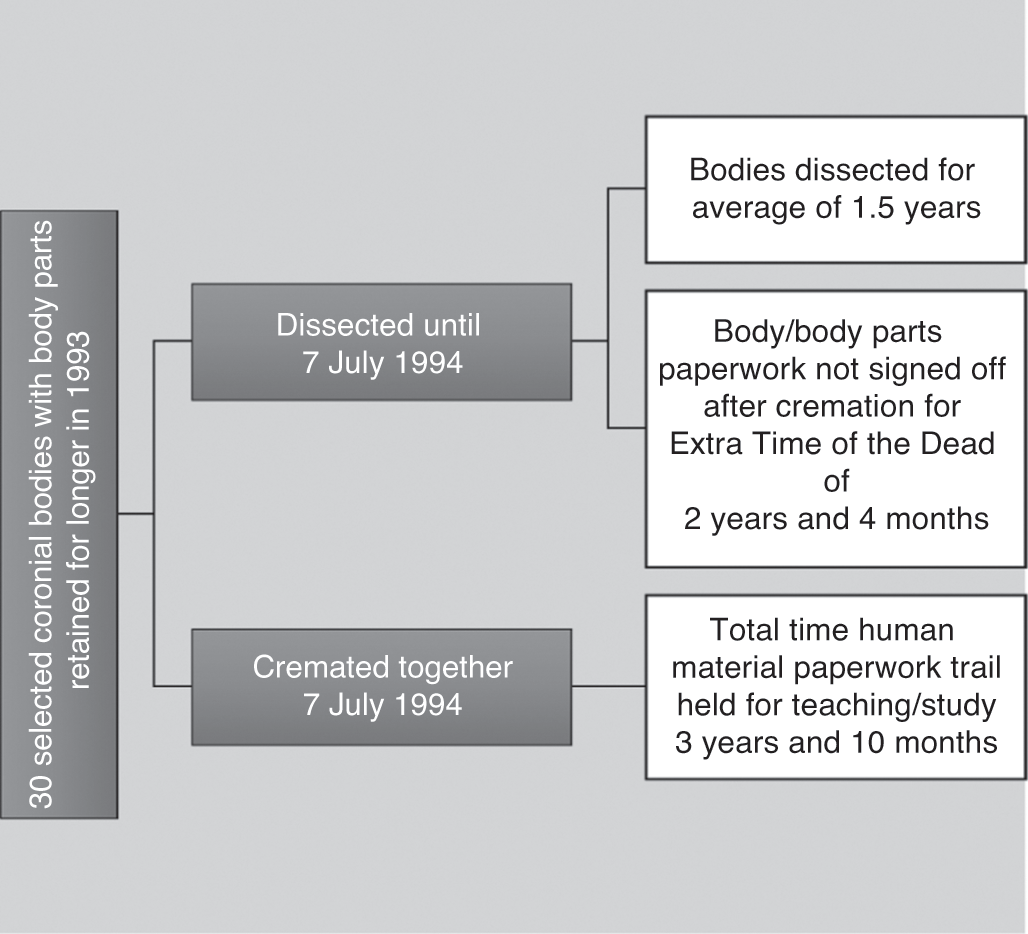

TAB was born in North London at the end of the WWII to parents (Mr WAB and Mrs HAB) who had married in their twenties sometime in 1938.14 They spent their savings on a small deposit to mortgage a three-bedroom house in Hendon. Having rented a property during the first year of their marriage, they wanted stability at home to start a family. Like many of their wartime generation, the ABs did not want to waste time. Their philosophical attitude was that if Mr WAB died at the front, then Mrs HAB would have the consolation of children. In Hendon during WWII, Mrs HAB gave birth to two boys – one in 1941, the other in 1945. She conceived each sibling during Mr WAB’s leave of absences from the armed forces. Detailed record linkage work reveals that whilst the eldest child (RAB) was to survive the ‘Great Fog’ of 1952, his younger sibling (TAB) did not. On 5 November 1952, TAB ‘died from pneumonia’ aged 7 in hospital. Under normal circumstances, once the funeral had been staged at a local church, his short life story would have ended but for the fact that he had died from prevalent pneumonia and his small body was thus a very valuable research and teaching tool for a medical profession facing a deepening epidemic of this deadly disease. Remapping its material journey from emergency admission to dissection and burial reveals the multilayered, hidden histories of a hospital coroner’s case. For the first time, we can trace a series of discrete research steps that were never officially recorded (Figure 4.1) but which go to the heart of attitudes towards body ethics in the immediate post-WWII era.

Figure 4.1 Remapping the threshold points of the dissected body and body parts of TAB, 5 November 1952–31 March 1954.

On the night TAB died, an ambulance transported him from Hendon to Harperbury Hospital near St Albans in Hertfordshire.15 Bonfire Night was a busy time for the emergency services in North London. Yet, this does not explain why a small boy breathing poorly went on a thirty-minute road journey about fifteen miles from home to hospital. There were four logistical issues shaping the local GPs decision-making. These helped to create research threshold points, stage-managed by an actor network of hospital staff, anatomists, a coroner and his pathologist. The first consideration was that out-of-doors most local people walked to and from work with a handkerchief over their face, often covered in a layer of coal dust from London’s dirty air. The ‘Great Fog’ of 1952 would culminate in politicians on all sides of the House of Commons passing the Clean Air Act (4 & 5 Eliz. 2 c. 52: 1956) as a national priority.16 The GP thus judged it prudent to move TAB out of the immediate area of the contagious pollution in Hendon. If air pollution was foul at the top of Harrow hill, 406 feet above London, then it was self-evidently best to remove the patient out of the capital altogether. Even so, a second practical factor shaped the decision-making too.

During WWII, St Bartholomew’s Hospital developed very close links with medical services at Hill End Hospital in St Albans.17 Once the site of an asylum and then re-designated a mental hospital in 1913, Hill End was requisitioned by the Ministry of Health during the Blitz to evacuate as many civilian casualties as was feasible out of central London. Hill End staff and those of St Bartholomew’s thus worked closely together. Medical personnel networked likewise with nearby Harperbury Hospital. In the 1950s, NHS staff continued to co-ordinate as they had done in wartime when the healthcare system was struggling to cope in the capital, as it was during the severe winter fog. Even so, a third logistical problem was a severe ambulance shortage in 1952.18 There was little point ordering a transfer into central London. Its inevitable delay meant TAB might never reach on time the critical medical help he needed at either Great Ormond Street in Bloomsbury or St Bartholomew’s Hospital in the City.19 He headed therefore for St Albans in the ambulance.

A fourth logistical factor was the fact that TAB’s family doctor faced a technical problem. His young patient had a bad attack of pneumonia, but there was a medical supply problem. The Chief Medical Officer (hereafter CMO) for England and Wales highlighted the key issue in the BMJ at the end of 1951:

There is a serious world shortage of x-ray films, due to increasing usage in all countries. In this country, usage during the first six months of 1951 was 16% greater than in the corresponding period of 1950 and was at a rate about 60% greater than in 1947. Production has been expanded and manufacturers have greatly improved their productivity. Nevertheless, it has not been possible recently to satisfy all hospital demands. New plant is shortly to be installed by manufacturers and should afford some measure of relief. Meanwhile, the present difficulties can be eased if all hospitals will exercise strict economy in the use of films and eliminate waste, particularly in processing.20

The CMO stressed that: ‘Economy in film production should not take precedence over the efficient examination of the patient’; nevertheless, it was necessary to ration X-ray films. An NHS directive stated that ‘only experienced clinicians’ were to be permitted to order X-rays in general hospitals. Nobody beneath the rank of a registrar could apportion precious film. In an emergency, the patient would be triaged and sent to hospital premises that had enough X-ray film to manage the critical condition. TAB thus had to journey out of central London to Harperbury Hospital at St Albans.

Once sent farther afield, another NHS stipulation complicated the accident and emergency protocols on 5 November 1952. On the night TAB died, the radiologist on duty was not authorised to X-ray a common condition like bronchial pneumonia just because they suspected its presence in the lungs of a young patient. A consultant on call was the only person who could make TAB’s case a clinical resource priority. The hospital management committee’s attitude was that there was little point in filming a fatal condition which medical intervention could do nothing to heal in a pre-antibiotic era. The BMJ had been critical of radiologists using what it called an ‘omnibus technique’: that is, doing radiology on all suspected cases as a matter of course regardless of the clinical prognosis. NHS resources were scarce and the subject of intense funding debates, straining central-local relations in 1952.21 In the case of TAB, there was an ambulance available to take him to St Albans where a supply of film was available. On arrival, there would be a specialist waiting for him with the authority to order a priority X-ray at Harperbury Hospital. Judged against these logistical criteria, moving TAB out of the Hendon area seemed to offer his best chance of survival. Even so, it is evident that the GP of the AB family had to work with a complex set of resource-allocation shortages on 5 November 1952. They explain why TAB’s body became available for dissection and medical research outside inner London.

On closer inspection of the case files, what cannot be determined from the surviving medical notes is whether (or not) TAB had an underlying medical condition from birth. This may have made him more vulnerable to pneumonia and might provide a further explanation as to why he was sent specifically to Harperbury Hospital rather than Hill End in St Albans with whom St Bartholomew’s had very close working relationships. Harperbury had a long history of treating those defined as suffering from mental incapacity in childhood according to the Mental Deficiency Act (3 & 4 Geo. 5 c. 28: 1913). The categories were:

a) Idiots – Those so deeply defective as to be unable to guard themselves against common physical dangers.

b) Imbeciles – Whose defectiveness does not amount to idiocy, but is so pronounced that they are incapable of managing themselves or their affairs, or, in the case of children, of being taught to do so.

c) Feeble-minded persons – Whose weakness does not amount to imbecility, yet who require care, supervision, or control, for their protection or for the protection of others, or, in the case of children, are incapable of receiving benefit from the instruction in ordinary schools.

d) Moral imbeciles – Displaying mental weakness coupled with strong vicious or criminal propensities, and on whom punishment has little or no deterrent effect.22

The hospital’s typical patient profile also included disabled children born with genetic conditions such Down’s syndrome or cystic fibrosis, impacting on their health profiles, learning needs and schooling proficiency. As one of the hospital’s first medical attendants, Dr H. E. Beasley, explained in Kelly’s Directory of 1937, Harperbury Hospital first opened as the Hangers Certified Institute in 1925. It was located on the site of an old WWI aircraft hangar, and the land was recycled to create a ‘colony for mental defectives’ in the 1930s:

The Middlesex Colony, begun in 1929, was opened on 20th May, 1936, by the Rt. Hon. Sir Kingsley Wood, M.P. Minister of Health. The Colony is intended for mental defectives who are socially inadaptable in the community, or who are neglected or without visible means of support. Male defectives who are capable of being employed are provided with suitable agricultural occupations on the land, or at various industrial occupations in the Colony’s workshops. Female defectives are suitably employed in the laundry, general kitchen or workrooms. Children who are capable of it are given various simple occupations. The patients live in separate ‘homes’ of the villa or pavilion type. The Administrative Centre, consisting of the main administrative offices, dental and surgical clinics, dispensary, central kitchen, reception hall, workshops, laundries, &c. has been built on an axial line running north and south, the Colony buildings for male and female being placed east and west around and overlooking playing fields. An isolated site on the south side is allocated for the children’s section.23

Nursing staff and a medical superintendent lived permanently on site. They supervised the medical cases using a wide variety of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions including art, drama, sport and daily farming activities for residents. The aim was to promote the benefits of occupational therapy for mental well-being. Under the NHS in 1948, the Middlesex Colony was renamed Harperbury Hospital in 1949.24 There was, however, more continuity than discontinuity in its healthcare provision. It often took in mental-health patients referred from the North London area during the 1950s. TAB thus entered a well-known facility for treating physical and mental disabilities in childhood on 5 November 1952, and one in St Alban’s with close wartime associations with St Bartholomew’s Hospital: again circumstances that materially influenced what happened next.

When TAB died on 5 November 1952, official jurisdiction over his material body started to change medico-legal hands. This was a child, the death was unexpected and his body passed from the emergency team to the pathology department but overseen by a hospital coroner. As there would need to be a hospital post-mortem, the cadaver was preserved in formaldehyde from 5 November to 11 November. In these six days, TAB had no official legal status in the public domain. No death certificate was issued. The body did not technically belong to his parents. In property law, it was ‘Res Nullius – Nobody’s Thing’, as we saw in Chapter 2. The coroner with the co-operation of the pathologist now had to establish the cause of death. Ideally, they would do so with the parent’s co-operation to reassure them that the hospital was not guilty of medical neglect. Even so, this was not strictly speaking a legal requirement, and such ambiguities could be misleading for the family involved. Indeed, on closer inspection it is apparent that standard procedures involving this seemingly routine post-mortem were not straightforward in 1952. As Figure 4.2 suggests, step by step TAB’s body and body-parts moved into the jurisdiction of medical science, creating an elongated and hidden afterlife of the body which was not ended until TAB was buried some fourteen months later.25 In his hidden history of the body, there are three noteworthy time gaps from detailed record linkage work. These provide important clues about the research threshold points of medical science’s work on TAB.

Extra Time of the Dead

In the early 1950s, GPs made a number of complaints to the British Medical Association that the NHS seldom informed them officially about the death of one their registered patients on a hospital ward. As a result, there was a lot of concern and considerable confusion about who should issue a death certificate to bereaved families and when exactly a family doctor should do it. In the interim, a bureaucratic space opened up for the medical research community to obtain jurisdiction over the dead for longer than it appeared. The General Medical Committee Conference thus informed the BMJ on 17 April 1954 that to resolve the confusion, from now on: ‘it has been agreed that a letter will be sent … drawing attention to the importance of ensuring that general practitioners are promptly notified of the death or discharge of hospital patients’.26 TAB’s dead body entered this extra time of the dead in its paperwork too, as Figure 4.2 illustrates.

Harperbury Hospital did not issue a death certificate for twenty-six days until their coroner eventually registered it officially on 1 December 1952. This happened at St Albans Registry Office, even though the child had resided prior to death with its parents in Hendon. In the meantime, TAB’s body became a site of negotiation and tension over the professional remit and standing of different groups of actors in the post-death process. We see such tensions clearly played out in early November 1952, just before TAB’s death. A concerned correspondent to the BMJ noted:

Pathologists’ Fees for Coroners’ Necropsies

SIR,-The salaries of the coroners in the County of London have again been increased. Everybody will approve, although the approval of the pathologists who serve them will be mixed with envy. Since the Coroners (Amendment) Act of 1926, the fees payable to pathologists for coroners’ necropsies have not been increased. Are not these pathologists the only group of the community who have had no increase of pay for more than a quarter of a century?

The Committee on Coroners, under the chairmanship of Mr. Justice Jones, has reported to the Home Secretary, but, as a matter of equity, the fees payable by coroners to pathologists should be increased without waiting for the report as a whole to be carried into effect. Cannot the B.M.A. exert some pressure on behalf of the admittedly small number of its members who carry out necropsies for H.M. coroners?27

A matter of days before TAB’s body entered Harperbury Hospital professional disputes were holding up supply-lines of bodies for potential dissection. Disagreements about fees and salaries created the context for generating implicit disputes. Liminal spaces opened up because of the delay in the official process of moving the dead whilst pathologists and coroners argued about the economic basis of their status. In TAB’s case, we can explicitly observe the timeline and time-travels. Slowed down, these created a twenty-six-day gap between death and official registration. This did not mean that the body did not physically move along the chain of command or supply; it did. The crucial point to appreciate is that it had no official status in law and hence did not technically exist for its relatives. If the parents had wanted to object to what was happening to TAB’s remains in the twenty-six-day gap, they would have had no official knowledge to react to. There was no record-keeping for this missing period of almost four weeks. This was commonplace and it created the potential for a series of discrete research thresholds without the full knowledge of the bereaved. Remapping what happened next brings these threshold circumstances into sharper focus.

On 11 November 1952, ‘further examination’ of TAB’s body began once chemical preservation was completed. The hospital coroner deliberately used this legal phrasing because it was permitted by AA1832 and the Coroners Amendment Act (16 & 17 Geo. 5 c. 59: 1926), even though critics like Pearl Craigie had objected to it (unsuccessfully) in 1906 (as we saw in Chapter 3). The same legal framework remained in force and therefore covered the removal of TAB’s body on the morning of 12 November 1952 to the dissection room of St Bartholomew’s Hospital in central London. Listing hospital transfers like this as a ‘B’ (bequest) in the dissection register (generally marked in pencil), was, however, misleading. There is no surviving evidence to suggest that this young body was the result of a written bequest. Paperwork detailing informed parental consent prior to dissection is missing, or it was never created in the first place; alternatively, the anatomist on duty may have been lazy about form-filling and did it verbally, or he was in a rush on the morning of TAB’s arrival and did not do his filing properly at the end of the day. This ambiguity in the bureaucracy is nonetheless informative since it reflects the common way that many bodies were supplied at the time through an implied consent process (as we shall see later in this chapter).

Whatever the paperwork discrepancies in TAB’s case, it is noteworthy that St Bartholomew’s Hospital had been keen to improve its ‘mechanisms of body donation’ after WWII. Records show conclusively that a new scheme of bequests did not get officially under way until 1954 (Figure 4.4). This made it very unlikely that TAB’s body supply involved a full bequest from Harperbury Hospital involving the parents. TAB thus appears to have been transported into central London to be dissected under an older system of supply that did not require explicit immediate family involvement, similar to what happened under the New Poor Law. There was, as we saw above, a close working partnership already established between medical staff working in the St Albans area. This made it feasible and normal for an existing network of suppliers to play a pivotal role in the presentation of TAB’s body to St Bartholomew’s anatomists, following long-established protocols stretching back to AA1832. A commercial transaction in TAB’s case can, however, be ruled out; supply-fees were not permitted by the 1950s. On 1 July 1947, James Cave, Professor of Anatomy at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, ordered that: ‘Payments for injecting subjects was to be stopped.’ Henceforth all such ‘petty cash [was] to be handed to Miss [Dorothy] Woolaway’, Cave’s departmental administrator.28 The old system of paying petty cash fees to Poor Law officials for dead bodies, supplied from infirmaries and workhouses, was phased out.29 At the same time, the wartime practice of compensating hospital staff in St Albans doing chemical preservation work was revised (although actual supply-lines from the same premises renamed under the NHS did continue to the close of the 1990s: a theme we return to below). In the transition, TAB’s body was not a crude commodity as it would have been under the Victorian system of supply. Rather, it was now symbolic of the changeover from the dead-end of the old business of anatomy to modern-day ‘mechanisms of body donation’ organised by hospital staff. The rest of this chapter examines this process in more detail.

Research Recycling

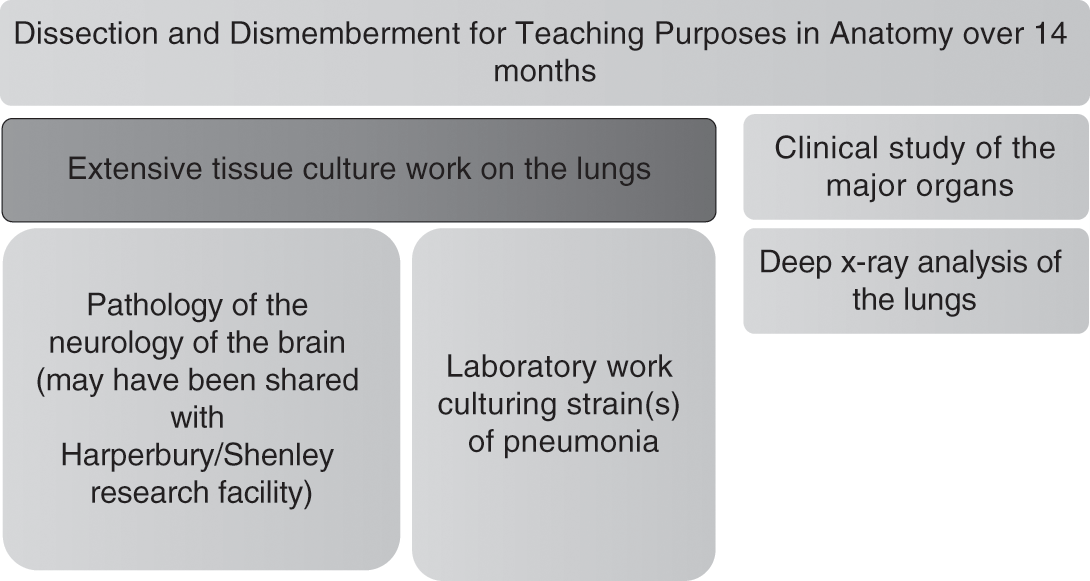

The fate of TAB’s body in terms of medical teaching and study highlights three key threshold points for the ethics of the body. The first is that TAB’s human remains were retained for 14 months in total before burial. That extended time frame effectively meant that the small corpse of a 7-year-old boy was dissected and dismembered extensively. In reality, there would not have been much material remains to bury at the end: less than one third at best. Seldom did doctors, coroners or pathologists explain this explicitly to grieving parents. Few could face such news on the night of a child’s death in hospital. Even if the family had been amenable to a body donation (and again, there is no evidence to confirm this in the record-keeping for TAB), in their initial bereavement their primary concern would have been for the dignity of their young offspring. This would have been a life-changing moment even for the most philosophical of family members. The very fact therefore of doing so much teaching and research on TAB’s human material created the potential for an implicit dispute to be generated. The process of consent was implied, not fully documented; even if it was done in some respect, it was at best ambiguous about all the research and teaching steps about to happen next. The extant evidence therefore points to the material fact that TAB’s parents were not given an opportunity to make informed decisions about their child’s potential to become bio-commons at this threshold point. Today, this is no longer permissible in the dissection rooms of medical schools, not simply because HTA2004 outlaws it but also because teaching facilities have now adopted a voluntary code-of-practice, which states that ‘no more than one third of a “human gift” to the medical sciences will be dissected’ for reasons of human dignity.30 While we must avoid judging past practice by standards which were not in force at the time, these new standard practices help to identify the liminal spaces and research threshold points that were routinely scheduled in case histories like TAB’s over the course of the second half of the twentieth century.

A second threshold for body ethics in the TAB case is the utility of the extensive dissection conducted as it became the focus of further work once teaching sessions on it had concluded. Figure 4.3 traces, through detailed record linkage work, the uses of body parts and tissue. The results are tangible. A 1961 study authored by clinicians working in the wards, pathology department and dissection room of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, and based upon research over the period 1949 to 1958, provided a new analysis of pneumonia. The research team reviewed the cases of ‘1,330 patients, 861 were males and 469 females; 303 were children under the age of 15’ who had all contracted persistent pneumonia. They concluded that typically: ‘some 634 (63 per cent) of the adults and 90 (30 per cent) of the children had a pre-existing disease. Respiratory disorders, particularly chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and cardiovascular diseases were by far the commonest concomitants.’31 Further clinical research led the research team to observe that: ‘In children, associated diseases and pulmonary complications were less common than in adults, but the mortality was high in infancy.’ Using deep X-ray equipment for which St Bartholomew’s was renowned at the time, medical evidence was found that: ‘The bacteriology of the sputum and the radiological appearances were similar to those seen in adults who did not have chronic respiratory diseases.’32 In other words, TAB was one of a number of cases whose lungs had been weakened by pneumonia straining his heart, making him ideal for further medical research study. He had thus been chosen by the hospital pathologist for ‘further Special Examination’ and in so doing he became a small but no less significant part of a medical mosaic that would eventually result in the drive for better precision medicine in the treatment of pneumonia. Yet against this benefit we must set the fact that the threshold points in Figure 4.3 were never mapped by medical science for his parents. Rather, they were kept behind the closed doors of private research facilities. This culture of secrecy was at the very least something that prevented the AB family from understanding the importance of their son for medical research, helping them to make some medical sense of their young son’s death.

A final threshold for body ethics is also highlighted by Figure 4.3. TAB’s brain was a valuable teaching and research tool even before it left Harperbury Hospital to travel to St Bartholomew’s on 12 November 1952. As we have seen, the Harperbury Hospital was at the forefront of occupational therapies to combat childhood learning disabilities and mental ill-health in the early 1950s. The hospital’s medical records are not sufficiently detailed to reconstruct whether parts of TAB’s brain may have been sliced and retained for research in-house, but nor can that possibility be ruled out either since it is noteworthy that clinical studies of brain matter happened regularly on site. It is conceivable in TAB’s case that his brain became a ‘control’, that is, retained but not sliced extensively. Equally, it is well documented in the extant records that childhood epilepsy was a feature of extensive brain research at Harperbury, with a particular focus on ‘hemispherectomy’. This method involved the removal of part of the brain, sometimes up to half in cases of severe epilepsy, on the basis that neurons in the young retain a neuro-plasticity to repair successfully after major invasive brain surgery.33 Known as ‘anatomical hemispherectomy’, it was carried out on both the living and the dead on site at Harperbury’s twin-research facility for brain studies called Shenley.34 It would be uncharacteristic of the research culture on site at that time if TAB had not been brought to the attention of the in-house team, either as a ‘control’ or a potential discrete brain-retention. Whatever the neurological circumstances, both at Harperbury and St Bartholomew’s, the actor networks existed since wartime to share in each other’s research priorities. TAB was thus a potential opportunity cost for the medical sciences. His cameo role in medical history illustrates the material fate of many others that entered similar premises, and highlights the process by which implicit body disputes might develop and the complex counter-currents of medical ethics, familial knowledge, openness and closed research processes that shaped the scale and meaning of body supply for research and teaching purposes in the recent past. In turn, we can generalise the lessons to be learned from the TAB case by switching our attention to material contained in St Bartholomew’s Hospital archives. This is where Richard Harrison (from Chapter 3) trained and, tellingly, what some medical students dubbed the Ministry of Offal in the press because it was one of the busiest teaching and research facilities in Britain. Here, we will hence bring to bear an ethnographic approach to the ‘mechanisms of body donation’ employed by the hospital and show how they operated both within the law and negotiated their way through it during the 1950s and 1960s. New data illustrates material afterlives, representative of the lost property of disputed bodies in modern British research.

St Bartholomew’s Bodies

St Bartholomew’s Hospital was a religious foundation first established at West Smithfield in 1123; thus, it is one of the oldest healthcare institutions in Britain.35 For almost nine hundred years, it has occupied a pivotal place in the heart of the City of London. On its flank stands the City Livery Companies near the Bank of England in Threadneedle Street along Lothbury, where many of the world’s leading finance houses are still located today. For centuries the hospital took in the dispossessed and sick poor, those often blighted by the hurly-burly of financial markets, sometimes bordering on the criminal that Punch exposed to ridicule in Victorian times. The courts of the Old Bailey were thus symbolically located just a short jaunt across the road from the hospital, which was within easy walking distance of St Paul’s Cathedral. Standing opposite the hospital gate was Smithfield meat market, too. Few missed the annual fair staged nearby. Strangers, passers-by and residents all came to enjoy the entertainments at the hospital’s King Henry VIII gate, erected in the Tudor period. After the dissolution of the monasteries, St Bartholomew’s survived the turmoil of the Counter-Reformation to emerge by the eighteenth century as a voluntary hospital with a long-term commitment to treat the sick poor from its endowments. This entailed embracing science and promoting a culture of teaching and research. That raison d’être spearheaded the expansion of medical education in the nineteenth century, so much so that St Bartholomew’s became the fourth-largest teaching facility in Britain by the close of Queen Victoria’s reign in 1901. Yet, for every new medical student recruited, there needed to be a constant supply of dead bodies to dissect. London’s destitute supplied the dissection table and thus helped to bring medical education at this famous hospital into the modern era.

The Medical Act (21 & 22 Vict. c. 90: 1858) stipulated that anatomical education was mandatory for every doctor. By the time those legal processes were extended in 1885, it was also a statutory requirement that each trainee should dissect a minimum of two cadavers (either whole bodies or enough body-parts to constitute two complete anatomies). This had to be done over a two-year anatomical teaching cycle at a designated teaching hospital like St Bartholomew’s, in order to qualify for general practice, surgery or midwifery. There remained, however, tensions over whether bedside training on the wards or research at the laboratory bench was the best way forward for a modern medical education. This tension was not resolved until after WWI when a redesigned curriculum tried to ensure that ‘medical education had a direct impact on clinical care’.36 As Keir Waddington explains, the ‘gap between science and the bedside had been bridged’ as a priority by WWII; nonetheless, ‘debate continued over the nature of academic medicine’. Waddington elaborates that by the early 1950s: ‘If science had been accepted as an integral part of a doctor’s training, old divisions between clinical and pre-clinical study were challenged as uncertainty grew about the location and content of training.’37 In many respects, dissection was at the centre of these ongoing debates because St Bartholomew’s had been extensively bombed in the war and its teaching facilities needed rebuilding to be world leading again. The NHS after 1948 tended to be slow about repairing this wartime damage, but committed staff pushed ahead to better integrate anatomical teaching with more specialised research facilities into the curriculum once more. Looking back, despite the problems of regeneration, many who worked on the premises in the 1950s recalled ‘golden years, with a sense of ever-expanding horizons’.38

Studying the dead in detail in this period is feasible because of the remarkable longevity of the accurate record-keeping at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. It has one of the best-documented archives in Britain and remains committed to sharing its past histories. Using such material, Figure 4.4 shows that 1,072 bodies were supplied for dissection from 1929, when the New Poor Law ended, until 1965. This reflected an organised network of suppliers. Four observations set in context the acquisition of these bodies and the implied system of consent that kept it functioning. The first observation is that the end of the New Poor Law had an immediate impact on the supply of the destitute for dissection from asylums, infirmaries and workhouses. As this author has documented elsewhere, on average St Bartholomew’s Hospital had been able to acquire at least 50 cadavers each teaching year from the time of the passing of the AA1832 until 1929. Indeed, in the early years of the new legislation, supply levels had peaked at 70 per year. A total of just over 6,000 bodies (from around 60,000 generated across the capital as a whole) were bought from the dead-houses of Poor Law institutions to the hospital in the period 1832 to 1929.39 In other words, St Bartholomew’s share was a minimum of 10 per cent of the entire system of body trafficking in the capital. Since these figures represent just whole bodies, another 10 per cent should be added for trades in body parts too. The latter were always more profitable because more money was made from the corpse broken up into piecemeal transactions. St Bartholomew’s trading figures were thus never less than 20 per cent of the dead of London until 1930. The system functioned because generous petty cash payments persuaded people in the employ of body dealers to co-operate. It became a well-organised business of anatomy and the dead were a commodity that medical education expansion relied on.

This deep history matters, both for the interpretation in Figure 4.4 and the subsequent issues around body ethics in the twentieth-century. St Bartholomew’s had a lot of go-betweens in its employ to make this trafficking in the dead operate efficiently each night. It was commonplace for a so-called ‘undertaker’, really a body dealer, to be employed by the dissection room. That disguise hid the fact that they were buying and selling corpses on the London streets. Once the New Poor Law ended, all of these trading arrangements had to be renegotiated, and this took time. Consequently, St Bartholomew’s trading position went down from 70 bodies in 1929–30 to 52 bodies by 1934–5, a loss of nearly 20 per cent. The dissection room staff then put a lot of effort in 1936–7 to try to improve supply-lines again, but they could not prevent them dropping by another 10 per cent to around 40 per year by 1937. By the start of WWII, these figures had stabilised to about 45 bodies each teaching cycle, but it was more difficult to maintain supply-lines in the Blitz once more people evacuated out of London. Putting this trading activity into its broader perspective, the 1939–40 supply-rate was just 64 per cent of the supply levels there had been in 1929–30. This was a crucial 36 per cent reduction overall at a time when medical student numbers were expanding. When Richard Harrison (see Chapter 3) signed up for a new medical career in 1939, he was unaware of this supply problem. It never featured in the recruitment literature sent out to prospective students. As the 1930s had been a very difficult economic decade after the Wall Street Crash, everyone inside the medical profession assumed that the dead of the destitute would be available in large numbers due to startling poverty levels (as they had been in late Victorian times), but this was not the case. Subscriptions to burial clubs run by trade unions and small co-operative societies provided the means to bury the dead and hence alleviated the stress of those subsisting on the threshold of relative to absolute poverty.40 This meant that St Bartholomew’s relied on a much narrower range of former Poor Law institutions, many of which became County Council care-homes for the aged, for its regular supply needs.

A second observation is that during WWII supply levels dropped sharply. This supply pattern matched that of WWI. Those medical students, like Richard Harrison, evacuated out of London to study at Queens’ College, Cambridge, together dissected no more than thirty bodies per year for the duration of 1939–45. It was thus much more common to dissect parts of bodies rather than whole cadavers over a two-year training cycle. This sets in context Harrison’s recollections of daily tensions in the dissection room about when to turn a body over to make sure everyone got a chance to do an anatomical procedure. In other words, dissection was piecemeal and this reflected the fact that men recruited into the armed forces died abroad in greater numbers, rather than at home in poorer parishes where they had traditionally been sold on in death. The majority of dissections during the war were therefore on the aged. Middle-aged women did not tend to feature in the dissection registers because they had vital war work in munitions factories, took on more childcare responsibilities and were generally nursed at home even when seriously ill because of their value to the makeshift economies of the labouring poor. In terms then of calculative reciprocity, women until their 60s continued to be cared for by their kinship networks. Only those worn out by a life of hard work, aged, friendless and lonely would eventually come into the purview of the ‘mechanisms of body donation’ supply-lines of St Bartholomew’s.

This situation did not improve in 1945. Until 1954 and the introduction of a new body bequest drive, supply-lines were under pressure, such that just thirteen bodies were acquired in the teaching year of 1953, and this despite the high death toll in the ‘Great Fog’ of 1952. At no time in the entire history of dissection had supply-lines been as difficult to sustain. Even under the Murder Act (25 Geo. 2 c. 37: 1752), supply-lines were relatively buoyant compared to this.41 Anatomists indeed often complained that the murder rate did not keep up with demand from medical students whose numbers increased sixfold; nonetheless, AA1832 resolved this situation. In the meantime, supply-lines nationally tended to be on average fifteen a year from 1752 to 1832. In the capital, however, by 1800 supply-lines were much worse than in provincial England: they peaked at seventeen a year in 1815 in the provinces compared to just three bodies per year in London. This meant that St Bartholomew’s in 1953 found itself with a very old supply problem more akin to that of the early nineteenth century than one normally associated with modern medical research in the standard historical literature. It meant that bodies like TAB took on a symbolic importance and a lot of use was made of them, as we have seen.

Finally, it is evident from Figure 4.4 that the introduction of a body bequest scheme from 1954 had an important effect, bringing supply to about 30 per cent of its early twentieth-century peak. During the 1960s, students at the hospital would have had access to around thirty corpses each teaching cycle. Yet, this is only a partial picture because there were also important changes to the composition and character of the bodies supplied, as further detailed record linkage on individual cases reveals. They illustrate epidemiological trends. In other words, we need to compare TAB’s material journey (from pneumonia death to dissection on into further research cultures) which was happening in parallel with other medical research activities at the time. It is important to examine these too because otherwise we will not gain a comprehensive enough historical picture about how a system of implied consent operated, the motivations driven by underlying disease trends, and thus nosology factors potentially shaping research priorities inside the actor network of anatomists, coroners and pathologists working together.

When each new body entered the dissection room, there was an important opportunity for the staff on duty to check the death certificate, which was often inaccurate. They stated the proximate cause of death, that is, the last ill-health episode the person died of. These were not reliable in terms of epidemiological trends in the general population because each GP would not have necessarily known the outcome of a detailed post-mortem. The poor were often signed off as ‘heart problems’, ‘diseased’ or ‘dying from neglect’, for instance. And, thus, expensive post-mortem costs were saved. Anatomists therefore as a matter of course always conducted their own autopsy before commencing teaching. They re-checked the pathology of death and arrived at a more accurate underlying morbidity result. This having been done, that then raised the possibility of doing further medical research on the body, its parts, organs and tissue in question. In Table 4.1 we thus see in the left-hand column the common certified causes of death before they underwent autopsy in the dissection room. In the right-hand column are listed the common ways that anatomists assessed the underlying potential for further medical research once they had arrived at more accurate morbidity results. In this way, staff on duty were able to identify a range of complications and to follow an enhanced set of research and teaching priorities. Thus, when the dead body of a male aged 70 named CD arrived on 25 March 1950, what appeared to be death due to a combination of mental and physical degeneration reflecting ‘decline in old age’, on closer examination proved to be caused by ‘tubercular enteritis’.42 CD had lived in abject poverty and died in the old St George’s Workhouse Infirmary on Mint Street in South East London. The medical premises, even in the 1950s, were still in use. The NHS occupied them to treat some of the most vulnerable residents of Southwark, a parish traditionally linked with high levels of death in Victorian times. Today, this association with typical disease patterns of endemic poverty continues, since ‘gastrointestinal and peritoneal tuberculosis remain common problems in impoverished areas’.43 Presentation of the disease TB in the abdomen has always been very difficult to diagnose. Even so, it is often present in the urban, elderly poor. Before the introduction of laparoscopy, it was hard for doctors to see the bacterium growing in the GI tract (in the ileocecal area, the ileum and the colon); in virulent cases, any area of the gut might be infected. Generally, it is still connected to poor immune levels (notably in HIV patients), but in the past tended to be a reflection of economic patterns of deep social deprivation and diseases associated with consumption.

| Death certification date(s) | Disease classification(s) | Potential for research |

|---|---|---|

| 1930–65 | Diarrhoea, Mental & Physical Degeneration | Old Age, Dementia & Decline |

| 1945–50 |

| Heart Attack Prevention |

| 1950–55 |

|

|

| 1955–60 |

|

|

| 1960–65 | Cerebral Haemorrhage |

|

CD was, therefore, typical of the sorts of bodies still generated for dissection at St Bartholomew’s from long-established links to the basic healthcare facilities of the New Poor Law. The dissection register states CD’s retention for teaching and research purposes lasted from 25 March 1950 until the start of 1951. In nine months, every opportunity was taken to culture the strain of ‘tubercular enteritis’ in the abdomen area, and to do further research on major organs including the heart and lungs. As with TAB, medical students cut up CD extensively. Eventually Robert Hogg (a so-called ‘undertaker’, really body dealer) buried what little remained. Hogg, according to the dissection accounts, also selected bodies from Guy’s Hospital too and took them to the Examination Hall if he thought they would be useful specimens for students’ oral tests. CD appears to have been one such case, and since the records confirm his destitution, this typical profile matches others in the sample size. It is likewise informative that the taking of his body from St George’s Infirmary was part of an implied process of consent from many other similar institutions because he was friendless in death. There was nobody to dispute what was happening except the infirmary staff, and it was not in their interests to upset a network that by the 1950s was deeply embedded into a chain of body supply that stretched as far back as 1834 when the New Poor Law was established. Nobody therefore searched for CD’s far relatives to check on his last wishes; although ethical standards at that time did not require this, the inaction does reveal a lot about questions of loneliness and autonomy in death, and the potential for implicit body disputes.

We often think that the current healthcare crisis in loneliness is a recent social phenomenon, but it occurred often in the early 1950s. In fact, the social anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer wrote in Exploring the English Character (1955 edition) about how ‘most English people are shy and afraid of strangers, and consequently very lonely … especially in old age’.44 Anatomists therefore deployed that social situation without fear of official censure. Indeed, the Lancet in one of its most forward-looking editorials in 1949 forewarned, ‘The plight of old people is one of the [sic] biggest and most embarrassing problems facing the National Health Service.’45 That fact of life was a boon for the medical sciences, as many similar entries to CD in the dissection books confirm. Indeed, it is feasible not only to retrace the three discrete thresholds in his case (teaching, heart-lung research, culturing tubercular enteritis) but also to reconstruct other ‘undertakers’ that were used to bury what little remained at the end of life because a tally of those who doubled up as body dealers was kept, as Table 4.2 shows. Many worked for New Poor Law institutions. Most stayed on the staff when premises were renamed, transferred to the NHS. The records facilitate therefore the opening of the door marked ‘KEEP OUT – Private!’ highlighted in Chapter 3.

Table 4.2 Undertakers that buried dissections from St Bartholomew’s Hospital, 1930–1965 (including those in the employ of Guy’s Hospital)

| Undertaker | Trading premises | Hospital supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Merett & Son | 519 Hackney Road, NE London | St Bartholomew’s |

| R. Hogg | 30 St George’s Road, Southwark London | St Bartholomew’s & Guy’s |

| • Burials at East London Cemetery Plaistow | ||

| J. Gaulborn | 61 Greyhound Road, Hammersmith London | St Bartholomew’s |

| J. Field | 183 Blackfriar’s Road, SE1 London | St Bartholomew’s & Guy’s |

| • Burials at East London Cemetery Plaistow | ||

| J. Kenyon | 45 Edgware Road, Paddington London W2 | St Bartholomew’s |

| • Burials of Roman Catholics | ||

| Askton Brothers | 252 Clapham Road, SW9 London | St Bartholomew’s & Guy’s |

| • Burials at East London Cemetery Plaistow | ||

| E. Napier and Sons | 157 Lancaster Road, Notting Hill W11 London | St Bartholomew’s |

The system of supply therefore afforded dignity and respect in death, and did so across religious denominations, but equally the network of body dealers disguised as ‘undertakers’ that facilitated a system of implied consent stretched across London, with some longevity. In the next section, we therefore explore this hidden history of the dead in further archive detail, because the historiography has tended to lose interest in the dead at burial – failing to appreciate that to get to burial could involve a complex medical research culture of pathways still to be mapped materially.

May-Die! Mayday! Mayday!

Disregarding such privacy notices personified by Table 4.2, it is notable how many healthcare institutions listed in the St Bartholomew’s dissection registers had close links with the New Poor Law. Often these premises were recycled under the NHS, continually hidden from public view. Some key examples stand in for many at the time and illustrate the sorts of network suppliers generated that made a complex system of implicit consent function over time inside the modern system of supply. The Mayday Hospital situated at Thornton Heath in Croydon did this on a regular basis.46 For appearance’s sake it was styled the Croydon Union Infirmary and then renamed the Mayday Road Hospital in 1923. This was because in an era of widening democracy, voting rights had to go hand in hand with better healthcare provision or else welfare facilities looked like an empty political promise to ordinary people. By the time that the Croydon Corporation took over the premises in 1930 and then the NHS absorbed the local healthcare infrastructure in 1948, it seemed that the Mayday Hospital had embraced the modern era of universal medical provision. Yet, many local people did not see it this way. For despite the careful rebranding of the hospital under the NHS, its popular name was the ‘May-Die Hospital!’ So sensitive were the local NHS health committee to this slur of medical negligence that eventually the premises were renamed the Croydon Hospital to sever all associations with social deprivation and poverty. Even so, this did not stop St Bartholomew’s lobbying for body supply there in the 1950s. Thus, when a 76-year-old female died in Mayday Hospital on 3 October 1956, her body went to St Bartholomew’s at 10 a.m. on Thursday 4 October 1956. The patient had died from a ‘cerebral haemorrhage’ and the body was retained over 20 months for teaching and brain research until 7 July 1958. It was again buried by Hogg, the ‘undertaker’ and body broker go-between.47

This case in many respects is intriguing because of its mundane conclusion, despite a number of curious features. It resulted in a dreary death and disposal, representative of many examples in the dissection registers. The female named EF had a Jewish birth name.48 Yet, it was a cultural taboo in the Jewish community to delay the burial or cremation of the dead for more than twenty-four hours. Ideally, the interred body would be intact. The woman lived, however, at the time of her death in a Church of England home for retired deaconesses located at Staines near Heathrow airport. The balance of the evidence suggests that this association with the Anglican faith made donation feasible. Even so, the body was not marked with a ‘B’ to indicate a written bequest in the dissection register. The female in question was respectable, but poor. It was common for care-homes of the elderly to offset funeral fees by agreeing to donate bodies in return for the medical school bearing the costs of burial or cremation. There seems therefore to have been an implied assumption in this case that handing over the body was conventional, given the deceased’s relative poverty. Besides, if EF’s orthodox faith had been strong, it is unlikely that she would have been retained for twenty months without her Jewish family’s consent. Perhaps she gave such consent herself verbally and willingly, with the paperwork not processed properly. Or her ‘donation’ was implied from her modest personal circumstances and carried out by the care-home to save money. Whatever the motivation, Hogg buried EF at East London Cemetery in Plaistow, which was some considerable distance across the capital from her last place of residence in West London and far from the Jewish cemetery at Kensal Green. There does not therefore seem to have been any further family involvement by her Jewish kin. Here we glimpse someone connected to an Anglican community, amendable perhaps to the ‘gift’ of the body, but for whom the end-of-life experience was not so far removed from the friendless dead-end of others less fortunate than herself such as CD. Death was not just a common denominator; it could be a social leveller too. Determining who entered the system of implied consent often involved something as simple as slipping beneath everyone’s social radar out of reach in old age, a situation that the Sutton and Croydon Guardian reported on even as recently as November 2013. Today, Croydon University Hospital (CUH) still faces insufficient staffing levels, substandard cleanliness and long waiting times in accident and emergency, affecting the elderly; for, according to a newspaper investigative journalist: ‘CUH is not officially stated as the worst hospital in London but it is the most complained about earning the misnomer The May-Die, referring back to its former name Mayday Hospital before it was renamed University College Hospital in 2010.’49 In hidden histories of the dead, such repeated scenarios are noteworthy. They suggest considerable longevity, little chance to dispute what was happening with regards to implied consent, and a system that was all about recovering a welfare debt in death. Others who equally were perceived as a burden to taxpayers entered the same supply chain too.

Perhaps one of the most interesting features of the body supply to St Bartholomew’s in this period is that many cases came from former asylums and prisons. They thus encapsulate a central dilemma in modern medical research – namely, the exploitation of the unfortunate for scientific gain. We saw this criticism in Chapters 2 and 3 during the 1950s when articles and letters published in the medical press expressed ethical concerns about how to protect with legislation those suffering from anxiety, depression, and more serious mental-health conditions like schizophrenia. Some patients consented to drugs trials they could not comprehend fully, since informed consent was very difficult to monitor in the mentally vulnerable. The standard approach in the historical literature to this sensitive issue is to tally up all of the premises of incarceration that were involved in body-supply schemes, mapping their geographical alignment to assess the business of anatomy on a regional basis. Yet in the modern era, that geo-approach could be misleading. What really mattered to modern medical research was not just the physical location of potential bodies, but the over-laying of hidden histories inside medical spaces of incarceration. It was possible for a patient to enter a mental health establishment for general treatment, for instance, and then get caught up in the dissection system by virtue of how research pathways had accumulated inside the premises over time. One representative case illustrates how this worked in detail.

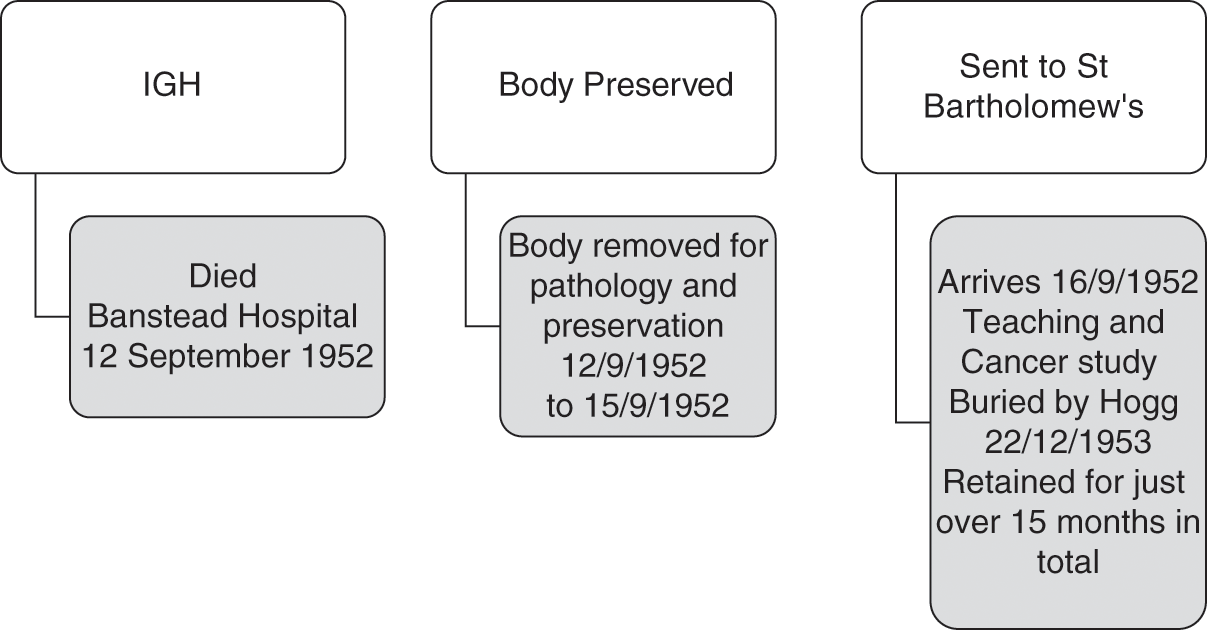

Thus, IGH was a 68-year-old female who died on 12 September 1952.50 She resided in a relatively affluent area of Notting Hill in London. Her home was grade-II listed and faced a garden square of some architectural merit. She was not therefore the sort of person that one would expect to end up on a dissection table unless she had agreed to a body bequest in her will, which does not seem to have been the case. So, how did she come into the medical purview of St Bartholomew’s? IGH had taken a decision to enter Banstead Hospital in Sutton towards the end of her life. She had contracted cancer and needed specialist nursing care.51 This institution, however, had a complicated healthcare history layered with meaning for the dissection system of supply. This IGH seems to have been unaware of in its entirety, but it did nevertheless have a bearing on her destination in death. Banstead Asylum first opened in 1877 with the capacity for 1,700 patients (615 males and 1,075 females).52 It was one of three asylums in Middlesex. The premises remained open to ‘mental defectives’ (broadly defined) under the New Poor Law until WWI. However, from 1889, Banstead came under the jurisdiction of London County Council. By 1912, it was a site covering 200 acres. On its 130-acre farm, patients did occupational therapy and learned self-sufficiency. After the war, however, with so many men returning from the trenches suffering from shell shock, institutional rebranding was commonplace. The premises became Banstead Mental Hospital. In 1937, it was restyled again as just Banstead Hospital, and it transferred to the South West Metropolitan Hospital Board under the new NHS by 1948. Various NHS reorganisation schemes from 1974 until the 1980s preceded its eventual closure in 1986. Often described as a ‘lost hospital of London’ its hidden history in the 1950s proved to be relevant for IGH’s body.

After being requisitioned during the war, by the start of 1950 the military had packed up and left Banstead Hospital.53 It once more became a civilian facility under the NHS. The bed capacity was now ‘2,599’, but in 1951 a decision was taken to designate the premises as a Regional TB Unit too.54 Here men that had contracted persistent TB, and were psychiatric patients, were treated. The female wards on the Unit also contained ‘21 typhoid carriers who were constant excretors’. Often standard treatments had failed to stem their contagious conditions. There were likewise a small number of ‘dysentery carriers’.55 A decision was taken to designate its 15 wards (each with a maximum of 60 patients) with special areas of clinical responsibility ranging from TB, epilepsy, typhoid, dysentery, VD, senility to surgical and psychiatric care. There were also ‘special rooms for disturbed patients’. An additional logistical issue was a ‘chromic shortage of nursing staff’ in the early 1950s. It took time to refurbish the wards to attract more specialist and general nurses, and, in the meantime, the plan was to open a new Clinical Psychology Unit from 1953. Once opened, art and social therapies were introduced. Treatments for persistent mental ill-health included: ‘leucotomy, deep insulin coma and ECT’. In 1951 the TB Unit for men was expanded to house 100 patients and surgical interventions were introduced such as ‘pneumo-peritoneum, pneumothorax and phrenic crush – or with chemotherapy, using a cocktail of streptomycin, PAS and INAH’. The antibiotic era had arrived at Banstead.

When IGH entered Banstead Hospital in the late summer of 1952, therefore, she came into premises deeply committed to the most modern research. Up to fifteen research pathways existed inside the hospital wards run on clinical research lines to facilitate better specialist medical work in-house. This also connected to external research facilities like those of St Bartholomew’s. IGH was not thus simply a lady suffering from terminal cancer; she had a patient profile that matched research pathways of some longevity and reflecting clinical priorities. Moreover, her cancer was clearly not ‘simple’. Even after extensive dissection her cause of death was described as ‘secondaries [sic] of carcinoma’. Evidently, the primary tumour was not found, and this, allied to the fact that she was in late middle age, but not elderly, seems to have made her an interesting subject for further cancer study. Indeed, St Bartholomew’s had an excellent reputation for cancer treatment in this period, and so she was an ideal body supply.56 In practice, IGH’s time travels were not dissimilar to TAB’s when we map her hidden history, as Figure 4.5 shows. In a period of low supply, the hospital was thus taking what it could get, but equally when it did have an opportunity to self-select the bodies chosen, these matched its research focus.

One final feature of the complex network of institutions that underpinned the St Bartholomew’s dissection registers is that there were increasingly very close links between this institution and the hospice movement in London. These started around 1948. One representative example involves IJ, aged 66, who died from ‘carcinoma of the stomack [sic] on 6 December 1948 in St Joseph’s Hospice in Hackney’.57 Located on Mare Street, it still treats the terminally ill today. It was established in 1905, and the Ministry of Health recognised the dedicated work of the nuns by 1923, officially designating St Josephs ‘a home for the reception of advanced cases of TB’. During wartime, the patients and nursing staff evacuated to Bath, and on their return in 1945 extensive bomb damage had to be repaired. Across Hackney, the nursing staff took in those needing end-of-life care, and they soon expanded by developing close links and clinical studies with Cicely Saunders, renowned for founding the St Christopher Hospice from 1958. The ethos of St Joseph’s Hospice has always been to help the poorest and dispossessed in society regardless of their religious belief, and this very much reflected its location in Hackney, the third-most-deprived area of London.58 Unsurprisingly perhaps it has always had close links to St Bartholomew’s, the main hospital for the sick poor in central London serving the East End. Thus, when IJ died on 6 December 1948, her body was retained by the hospice for an initial post-mortem and then chemical preservation until 19 December 1948, a time gap of thirteen days, before being sent to St Bartholomew’s for dissection. Once there, again teaching and cancer research were the features of the discrete research steps taken, with ultimate body burial some twelve months later. This was the same supply pattern occurring with KL, aged 82, who died in a hospice in Bournemouth on 14 December 1952, arriving at St Bartholomew’s to be dissected and diagnosed with ‘carcinoma of the colon’ by the anatomist on duty, some three days later.59 On this occasion, because KL had expressed a wish to the hospice to have a Roman Catholic burial, J. Kenyon, the ‘undertaker’, took charge of the internment after a total of some fifteen months of teaching and research on 7 July 1953.

Meanwhile, another major source of supply at this time was Salvation Army hostels. Thus, when MN, a male aged 56, died of ‘hypertension’ in a Salvation Army hostel on 20 May 1953, his last known address had a direct impact on his body going to St Bartholomew’s, where he arrived on 26 May 1953.60 It was studied until buried by Hogg in a multiple grave on 29 December 1954. The case was not dissimilar to OP, a male aged 85, ‘whose last place of abode was Whitechapel Infirmary’ when he died at Leavesdon Hospital on 1 December 1960.61 This was a deprived area of London where the Salvation Army were very active in rescuing the homeless found in dire straits on the streets and placing them in whatever former Poor Law premises where available close to death. Thus, OP was moved on to St Bartholomew’s within three days; his death from ‘myocardia degeneration’ was common but his body and body parts were still worth studying until 3 January 1962. Buried in a batch of six bodies in a common grave, there was little to inter at the end. This more extensive use of the human material reflected the much more detailed pathology from the 1960s in the dissection registers. At that time in 1963/4 when the scribe who wrote up the entries changed hands, the bodies became a surname in capital letters and just their initials. The clinical discourse of the medical sciences was being streamlined once more, and the ‘gift’ of the whole person disappeared into discrete research steps whose human identities were gradually downgraded to a summary in the record-keeping. The modern era of clinical research was now looking towards a more sophisticated biomedical future, and this extended the potential for an implied system of consent to be generated and re-generated, especially amongst the homeless of London. To engage with that context, it is essential now to track forward in the record-keeping to the 1990s and examine in our penultimate section the scale, scope and clinical reach of anatomical records on a national basis.

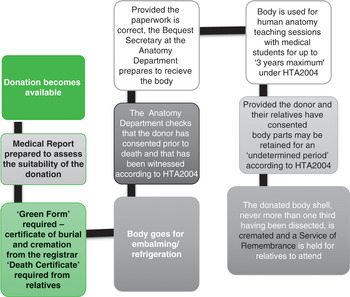

A National Picture – Remapping Donation and Dissection

The NHS public enquiries into organ retention that were the catalysts for HTA2004 established three things that are important for understanding the national scale of the implicit system of consent and its potential for body disputes by the 1990s. The first was that hospital coroners were crucial to the supply mechanisms of medical schools post-WWII. The second was that the need for high-tech pathologies on organs, body parts and tissue cultures complicated issues of consent by grieving relatives. The third was that even those amenable to donation had little material sense of what actually happened to each cadaver divided up in the name of medical science. One predominant issue was that detailed record-keeping had effectively lapsed during the 1980s because AA1984 did not reflect adequately the rapid pace of biotechnology. At the same time, the transplant era had begun and the scientific parameters of innovations, like drug-rejection therapies, were changing the course of research agendas inside the scientific community. In subsequent chapters, we will be engaging with this new biotech landscape in more detail, but before doing so, it is essential to try to understand the nature of dissection work in the recent past. The aim in this section is to examine the scale of the system of implied consent across England, and thus reflect historically on how many people could have been involved in disputing what was happening. Although some of the bereaved may have been in agreement, others might not have been; in fact, few got an opportunity to make that informed choice. Figure 4.6 thus provides an overview of rates of body donation around the country in the 1990s from figures made available by the Anatomy Office. This data is also displayed in Figure 4.7, with locations and rates of donation itemised for individual institutions in London. Then these figures are broken down again into annual rates of donation for all medical schools, and summarised in terms of regional versus metropolitan trends across Britain in Table 4.3.

| Medical school | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | Total(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REGIONS | 100 | 465 | 435 | 352 | 343 | 471 | 339 | 2505 |

| Birmingham | 0 | 5 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 72 |

| Bristol | 3 | 17 | 22 | 22 | 17 | 20 | 19 | 120 |

| Cambridge | 7 | 65 | 33 | 50 | 36 | 45 | 39 | 275 |

| Cardiff | 11 | 47 | 55 | 20 | 29 | 46 | 38 | 246 |

| Leeds | 10 | 47 | 22 | 18 | 33 | 48 | 41 | 219 |

| Leicester | 6 | 35 | 35 | 25 | 22 | 42 | 21 | 186 |

| Liverpool | 20 | 52 | 44 | 42 | 45 | 41 | 19 | 263 |

| Manchester | 9 | 38 | 32 | 26 | 29 | 48 | 15 | 197 |

| Newcastle | 5 | 19 | 30 | 20 | 21 | 18 | 11 | 124 |

| Nottingham | 8 | 44 | 49 | 43 | 44 | 55 | 39 | 282 |

| Oxford | 4 | 24 | 31 | 18 | 13 | 21 | 2 | 113 |

| Sheffield | 8 | 40 | 47 | 26 | 26 | 50 | 52 | 249 |

| Southampton | 9 | 32 | 21 | 29 | 16 | 23 | 29 | 159 |

| LONDON | 77 | 212 | 208 | 225 | 210 | 311 | 225 | 1468 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charing Cross Hospital | 10 | 19 | 21 | 16 | 40 | 46 | 29 | 181 |

| King’s College | 7 | 25 | 21 | 18 | 17 | 29 | 36 | 153 |

| QMWC* | 12 | 29 | 33 | 46 | 30 | 47 | 33 | 230 |

| Royal Free Hospital | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| St George’s Hospital | 13 | 37 | 35 | 33 | 13 | 33 | 23 | 187 |

| St Mary’s Hospital | 9 | 16 | 19 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 0 | 95 |

| UCL** | 9 | 27 | 27 | 24 | 22 | 41 | 33 | 183 |

| UMDS*** | 17 | 53 | 52 | 70 | 72 | 98 | 71 | 433 |

| Totals overall | 177 | 677 | 643 | 577 | 553 | 782 | 564 | 3973 |

* QMWC = Queen Mary and Westfield College London

** UCL = University College London

*** UMDS = United Medical & Dental Schools of Guy’s & St Thomas’ hospitals London including Royal Dental Hospital of London (all merged again into King’s College post-1998)