Book contents

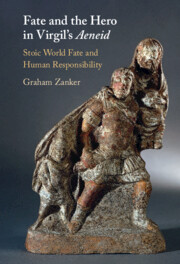

- Fate and the Hero in Virgil’s Aeneid

- Fate and the Hero in Virgil’s Aeneid

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Stoic World Fate and Virgil’s Aeneid

- Chapter 2 Fate and the Human Responsibility of Dido and Aeneas in Aeneid 4: A Case Study

- Chapter 3 Stoic World Fate and the Gods of the Aeneid

- Chapter 4 Stoic World Fate and the Humans of the Aeneid

- Chapter 5 Stoic World Fate and Roman Imperium in the Aeneid: Tragedy and Didacticism

- Book part

- References

- Index Locorum

- Index

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 April 2023

- Fate and the Hero in Virgil’s Aeneid

- Fate and the Hero in Virgil’s Aeneid

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Stoic World Fate and Virgil’s Aeneid

- Chapter 2 Fate and the Human Responsibility of Dido and Aeneas in Aeneid 4: A Case Study

- Chapter 3 Stoic World Fate and the Gods of the Aeneid

- Chapter 4 Stoic World Fate and the Humans of the Aeneid

- Chapter 5 Stoic World Fate and Roman Imperium in the Aeneid: Tragedy and Didacticism

- Book part

- References

- Index Locorum

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Fate and the Hero in Virgil's AeneidStoic World Fate and Human Responsibility, pp. 233 - 244Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023