‘German Princes and Nobility Rush Funds to Neutral Lands’, the Geneva correspondent of the New York Times noted in October 1918. Citing a Swiss banker, he observed that a ‘large proportion of the depositors bringing their money from Germany and Austria belong to the princely families, posing under assumed names’.Footnote 1 The work of a newsmaker in Europe between 1917 and 1920 must have been exciting and hopeless at once. From the Urals to the Alps, with each deposed monarch, with each exiled prince, European society was becoming increasingly unfamiliar. Many people inhabiting this large territory felt compelled to reinvent themselves under new banners: national democracies, classless societies, people without land. One of the tasks for the relatively new craft of world news reporting was to give readers a provisional image of this continent’s new appearance when its former faces had become mere phantoms. A focus on the German princes allowed grasping imperial decline of the Hohenzollern, Romanoff, Habsburg, and Osman dynasties at once, and in historical perspective. As a shorthand identity, ‘German princes and nobility’ reveals a slice of imperial decline of more than one empire.Footnote 2

At the same time, in Germany itself, even liberals were unsure whether a revolution had actually occurred. Not only did some Germans resent living in times ‘without emperors’,Footnote 3 contemporaries of liberal and even socialist leanings also expressed doubts about the viability of the German revolutions, which seemed feeble and theatrical compared to the images from Russia.Footnote 4 Somebody who is accustomed to images of the October Revolution – many of which, incidentally, were only produced retrospectively, in 1927 – would look in vain for an iconic equivalent from Germany.

In November 1918, the pro-republican Vossische Zeitung featured a confusing photograph of crowds gathered in Berlin on its front page, with a backward-facing Bismarck statue instead of the proclamation of the republic [Fig. 12].

Figure 12 Voss Zeitbilder, 17 November 1918, 1

It took the newspaper several days to change its name from ‘Royal Berlin newspaper for political and intellectual affairs’ to ‘Berlin newspaper for political and intellectual affairs’. Even on the five-year anniversary of the revolution, its weekend supplement showed no photographs from November 1918. Instead of images of crowds, the editors placed a large map of the world on the front page, which advertised the need for radio networks in post-war Germany, featuring the Atlantic Ocean more prominently than the continent of Europe [Fig. 13].Footnote 5

Figure 13 Die Voss, Auslands-Ausgabe, 45 (10 November 1923), 1

There was a debate whether to blow up the statues of Prussian kings adorning the Alley of Victory (‘Siegesallee’), an unpopular project initiated by Wilhelm II to commemorate the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and derisively called ‘Alley of Puppets’ in Berlin. It had only been completed in 1901 and included a genealogical parade of German rulers from Albrecht of Prussia, the last grand master of the Teutonic Order, to the Prussian King Wilhelm I. The satirist Kurt Tucholsky asked himself: ‘What will come of the Siegesallee? Will they drive it out of the city towards the New Lake because it is too royalist, too autocratic and too monarchist? […] Will they maintain the statues but place new heads on the same necks? […] And was all that learning of their names for my exams in vain?’Footnote 6 In the end they remained in place until Albert Speer’s grand plan to make Berlin fit for the Nazi empire forcibly removed them to a new location in 1938, where they were partially destroyed by allied bombs, then demolished under the auspices of the British and Soviet occupation, the remaining figures buried in the ground, only to be restored and reconstructed in 2009.Footnote 7

Hans-Hasso von Veltheim, the officer who had served in the reconnaissance photography department of the Saxon royal army in the First World War, confessed that he experienced the European revolutions as a ‘purifying and revitalising’ force that may yet ‘constitute a large step forward’.Footnote 8 This did not prevent him from serving as a volunteer officer in a dismantled Cavalry Division of the imperial guard in Berlin in 1919. Under the leadership of Waldemar Pabst and Reichswehr minister Gustav Noske, this division was chiefly responsible for crushing the socialist rebellions in Berlin in early January 1919. But when the Spartakists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were assassinated in the same month, Pabst himself was suspected of masterminding the murder. Veltheim chose to attend their funeral in civil attire. He confessed to his wife that he was ‘deeply moved’ by the ‘composure of this immeasurable, enormous crowd’. Deputies from ‘Switzerland, Holland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, Warsaw, Vienna, Sophia’ were among the mourners, and the ‘funeral procession of a Kaiser could not have been more ornate, dignified and moving’. One of the ‘proletariat’, as he described it, even offered him a sandwich, although ‘the man knew’ that he was ‘Oberleutnant and Dr. phil’.Footnote 9 Choosing Munich as his base for the next years, Veltheim sympathetically witnessed the socialist revolution there. He corresponded with the anarchist Gustav Klingelhöfer, who was imprisoned for treason for joining the revolutionaries of the Munich Council Republic, particularly the Red Army group led by Ernst Toller.

While individual aristocrats, like the representatives of other social groups, aligned with a variety of social forces during the revolution, aristocratic families remained objects of critique in central Europe. These ruling families saw themselves as the descendants of families who, for generations, had acquired distinction in ruling over Europe’s vernacular populations of Slavs, Anglo-Saxons, various Germanic tribes, Celts, Galls, Roma, Jews, and other groups. In popular culture, the traits associated with most of these folk groups – visual features, professional affiliations, and such like – usually appeared as marks of stigma or inferiority; but for nobles, their special qualities were always marks of distinction. If in many traditional cultures, unusual physical traits are associated with some kind of evil – one need only to think of the image of the hunchback, or the witch, in the case of nobles, some traits of this kind, such as the Habsburgs’ protruding lip, were used to mark a special kind of familial charisma.Footnote 10

In the early twentieth century, German aristocrats had become objects of satire in Germany and in the Habsburg lands. The Munich-based satirical magazine Simplicissimus ridiculed the Ostelbian Barons as symbols of the old world. ‘Let them cremate you, papa, then you won’t have to turn so much later on,’ reads the caption on one caricature dating from 1906 [Fig. 14].

After the First World War, such jokes became more serious. Election posters made the expropriation of former princes into one of the key rallying cries for voters.

In Czechoslovakia, National Democratic Party member Bohumil Nĕmec argued that ‘nationally foreign […] and rapacious noble families’ had been causing harm to the Czech nation throughout history.Footnote 11 Ironically, his own Slavic surname, which means ‘German’, hints at the history of ethnic relations in his place of origin. The imperial nobility, previously backed by the ancient power of the Habsburgs in the region, became merely another ethnic German minority, which the new governments viewed as being on a par with others, such as the Sudeten Germans.Footnote 12 In both Russia and Czechoslovakia, German nobles were granted citizenship in the new states but were effectively barred from participating in politics and exercising traditional feudal privileges like holding court.

In other states, aristocrats were mistrusted due to the disproportionate privilege they had enjoyed under the imperial governments. In fact, in Germany, for instance, already by the beginning of the twentieth century some members of the nobility had begun to organize themselves like an interest group whose interests go beyond party affiliations, such as the Agrarian Union or the Colonial Society. A number of nobles joined conservative associations of nobles such as the Deutsche Adelsgenossenschaft or the Deutscher Herrenklub, founded in 1924 by Heinrich von Gleichen; many Baltic Germans joined associations such as the Baltische Ritterschaften, which had their seat in Germany, but were active throughout western Europe in the interwar period. Other nobles from the Russian Empire joined the Union de la Noblesse Russe in France, which was founded in 1925, or aristocratic charitable organizations. Others again, particularly members of dynastic families, were active in chivalric associations, such as the Order of the Golden Fleece, the Order of St. John, and others.Footnote 13 The very idea of an aristocratic association was a modern concept, and quite unlike the medieval knighthoods known from such groups associated with the Arthurean legends as the Knights of the Round Table or the Order of the Garter. The modern associations which emerged in late imperial and republican Germany, the most prominent of which was the Deutsche Adelsgenossenschaft, were in fact alternatives to parties. In this way they were a reaction to growing parliamentarization, more than the enactment of a medieval ideal. The very idea of a Genossenschaft of nobles is, conceptually speaking, somewhat absurd. The modern equivalent of that would an imaginary CEO solidarity network, a sort of elite cartel that borrows its language from groups socially and economically inferior to itself. As such, they became what Stefan Malinowski has called ‘laboratories of aristocratic reorientation’, that is, places of mutual aristocrat recognition, as much as organizations serving the purpose of making aristocrats recognized by their non-aristocratic fellow citizens.

In Germany, a communist member of the German Reichstag recalled the words of none other than Robespierre, who justified the execution of Louis XVI as ‘not a decision for or against a man’ but a ‘measure for the public good, an act of national precaution’.Footnote 14 During the revolutionary period before the ratification of the constitution, the new governments of some former German principalities, for instance, Hessen Darmstadt, had already expropriated ‘their’ nobles as part of their revolutionary measures.

Although the constitutions of some smaller German states had ceased recognizing the nobility long before the revolution – for instance, the constitution of the Free City of Bremen from the period of the Kaiserreich did not acknowledge nobility as a politically privileged status – the majority of regional German constitutions had been dominated by the principles of monarchy and nobility, which only changed radically in 1918–19.Footnote 15 A government initiative for a mass expropriation of nobles, documented in photographs of election campaigns, failed to reach a quorum because only 39.3 per cent of the electorate voted [Fig. 15].Footnote 16

Figure 15 ‘Not a penny for the princes!’ Election poster from Germany, 1926. ‘Den Fürsten keinen Pfennig! Sie haben genug! -rettet dem Volk 2 Milliarden Den Notleidenden soll es zugute kommen!’ [Not a penny for the Princes! They have enough! – save 2 billion for the people/It should benefit those in need!] Election propaganda car (1926); Aktuelle-Bilder-Centrale, Georg Pahl.

Members of the Weimar government discussed at length whether it was acceptable to allow members of aristocratic associations to become members of Parliament.Footnote 17 In the end, a compromise was reached whereby the princes lost some of their real state that had representative functions but were financially compensated for this effect of the law. However, as Schmitt and other critics of this measure insisted, abrogating rights from nobles set a precedent for future liberal legislation, which meant that under certain circumstances, states could redefine the basic principles of legitimacy in their society.

In his role as a legal counsel to the Weimar constitutional court, Carl Schmitt saw the attempts to inscribe derecognition of nobility into law as setting a dangerous precedent. Comparing the situation with the French Revolution, he argued that with the execution of a king (such as Louis XVI), both the person and the office of the monarch were simultaneously eliminated. This model of reform-by-regicide could not easily be applied to the much larger number of European aristocrats. Unless one wanted to resort to assassinations of individuals with noble names on a mass scale, as had happened in the Soviet Union, this could not be extended to an entire social class within the framework of a liberal constitution.Footnote 18 However, even when laws abolishing the nobility were effective, their effect amounted to the abrogation of the rights of an entire social group, setting a dangerous precedent for depriving other groups of rights in the future. The legal definition of nobles as a ‘group of exception’ who can be expropriated by the state is particularly problematic for liberal legislation which is predicated on the a priori equality of all of the subjects of the law.Footnote 19

The republic was in a dilemma: the existence of aristocratic privilege threatened to derail the new ideal of political equality, but so did the possibility of expropriating nobles by law. The new constitutional assemblies ratified the abolition of the nobility by economic means, removing the prerogatives of primogeniture and title, and barring members of noble corporations from public office.Footnote 20 To give an example of popular attitudes towards the nobility in the German Republic, one K. Jannott, director of the Gothaer life insurance group, wrote to Reich Chancellor von Papen in 1932 that it would serve as ‘a great example’ if the noble members of government demonstratively renounced their nobility to show that they did not value the mere noble name ‘and that even by name they want to be nothing else but plain civic [bürgerlich-schlichte] citizens’. Thus, Jannott continued, the then-current government’s problems with accusations of being a ‘cabinet of Junkers and Barons’ could be decisively dismissed. ‘Noblesse oblige!’, Jannott cited the famous bon mot which bound nobles to serving the state and to honour their ancestors. He used it to incite nobles to give up their nobility in favour of the new ‘obligations’ associated with a republican regime.Footnote 21

Members of aristocratic families as well as those who deposed them had the spectre of Bolshevism before their eyes when they witnessed the revolutions in their regions. In Germany, where twenty-two dynastically ruled communities changed constitution between 1918 and 1921, this was particularly acute, but nowhere as immediately as in Hessen Darmstadt, since the wife of Nicholas II, who had been murdered with him by revolutionaries in Russia, was the sister of Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig. As Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig’s son Georg recalled, the way in which his parents were held captive on 9 November 1918 ‘was a very good imitation of the pictures of the Russian Revolution which we, too, had seen in the illustrated journals, and which apparently had started quite a trend’.Footnote 22

When Ernst Ludwig and his family found that they were not to be physically harmed by the revolutionary movement in Darmstadt but merely expropriated, the ex-Duke wished to bless the new government ‘for constructive work in the best interests of our nation [“Vaterland”]’. Ernst Ludwig wished to thank the new government ‘for the dignified way in which you have steered the wheel of the state under the most difficult circumstances and the often criss-crossing tendencies of the popular will, having managed a most serious transformation in the history of Hesse while avoiding all but the most necessary other hardships’. By ‘other hardships’, Ernst Ludwig was referring to the possibility of having been stripped not just of his status, but also of his life, as communist politicians at the time were calling for the beheading of Louis XVI. The letter was signed simply ‘Ernst Ludwig’, without titles.Footnote 23 In return for giving up political power and a few castles, Ernst Ludwig received financial compensation of 10 million Reichsmark.Footnote 24 However, the German hyperinflation rendered this transaction quasi meaningless.

The purposes behind abolishing the symbols of monarchy and nobility varied amongst the European states: in some cases, it was justified by the foreign heritage of formerly aristocratic families; in others, by their economic supremacy. Generally, the less radical European governments tried to address the problem of aristocratic privilege by making it impossible to combine membership in aristocratic corporations and service to the new states. In 1929, President Stresemann’s government determined that membership in the German Nobles’ Union, an aristocratic corporation, was unacceptable for members of the Reichstag, the ministries, and the army. The republican government of Austria had also passed a law concerning the ‘abolition [Aufhebung] of the nobility, its external privileges and titles awarded as a sign of distinction associated with civil service, profession, or a scientific or artistic capacity’. Ironically, Schmitt was right concerning the danger of the precedent, even though he himself helped bring to power the Nazi government, which went on to use the laws of the Weimar era to create its own mechanisms of derecognition. As Hannah Arent would later note, depriving Jews of citizenship in 1935 involved a multiple process of derecognition.Footnote 25 At the same time, Nazi officials could not decide whether or not the old ideal of the nobility contradicted their own ideology of the Aryan race.

In Austria, too, after 1919, nobles had become ‘German-Austrian citizens’, equal before the law in all respects.Footnote 26 During the parliamentary debates on the future of noble privilege in Austria, the social democrat Karl Leuthner argued that ‘the glorious names of counts and princes are in fact the true pillars of shame in the history of humanity’. His Christian socialist colleague Michael Mayr described the nobility as a ‘dowry of the bygone state system’ and thought it was ‘completely superfluous and obsolete in our democratic times’.Footnote 27 But the law itself made the difference clear: all other citizens could keep their imperial decorations, such as titles of civic or military honour. For example, the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski got to keep his doctoral distinction sub auspicii imperatoriis granted by Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef.Footnote 28 But citizens with noble names had to give up their imperial distinction and even their very names. In this sense, not all imperial privileges were derecognized, but inheritable privileges associated with the German princes were.

However, perhaps paradoxically, one of the unintended effects of this policy of abolishing aristocratic privilege was the emergence of a group of derecognized nobles who turned their newly obtained ‘classlessness’ and social homelessness into a new source of social capital. Their heightened sense of precarity made them appealing to an international elite in search of its true self, Europeans and non-Europeans. Many of them were jointly attracted to such new ecumenical and post-Christian communities as the Theosophical Society, gurus such as Krishnamurthi and Annie Besant, and the intellectual anthroposophism of the German philosopher Rudolf Steiner.

All these were to serve as instruments for shaping a new ideal of humanity that would build bridges between the proletariat and the old aristocracy, negating the authority of the bourgeois middle class with which the policies of derecognition were mostly associated. As Joseph Schumpeter explained in 1927, much of the transition from the old imperial regime to the modern republic depended on the old elites themselves, on the way in which they embraced giving up power for personality and the degree to which they were able to endorse the ideas of the new elites.Footnote 29 The nobility itself, as he put it, became ‘patrimonialized’, turning into a shared heritage.

Veltheim, like a vocal minority of other aristocratic intellectuals, reflected on the future international order from a European and an internationalist point of view. Even before the revolution, Veltheim and other nobles of his circle had attached themselves to modernist literary associations, where themes of European decline and homelessness, and the search for non-European culture, were prominent. Like Veltheim, many became attached to the political Left in the course of the First World War. Historians have so far looked at cases like Veltheim’s on an individual basis; and each biographer claims each of them to be singularly eccentric.Footnote 30 However, when considered together, their eccentricity appears to be a shared one; their ‘redness’ seems much more ambiguous; and the influence of their, however unusual, ideas happens to be much wider. Veltheim’s social circle is one of the intellectual communities that was very transnational in scope.Footnote 31

Veltheim’s world: homelessness and counter-culture before and after 1918

Hans-Hasso von Veltheim-Ostrau liked to entertain. In 1927, he inherited his paternal estate of Ostrau, near Halle, and was glad finally to be able to host his friends in a location worthy of his family name. Veltheim spent the first night at the castle chiselling out the ancestral crests of his ungeliebte stepmother, before introducing his own, supplemented by new portraits and busts of himself and a bespoke gallery of chosen ancestors, the Ahnengalerie. What followed were weeks and months of replanting, redecorating, rearranging and amplifying the eroded family library. Together with the rent that he was obliged to pay his brother Herbert by the rules of primogeniture, the Fideikommiss, the redecoration of the house cost him a considerable sum of money.

The castle of Ostrau, surrounded by a moat and a large park, had originally been built by Charles Remy de la Fosse in the early eighteenth century, an architect of Huguenot origin who was then also employed by several predominantly south-west German noble families, such as the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt. Like the Veltheims, they wanted to introduce French style to Germany, and now, Veltheim took the opportunity to reconnect to this tradition.Footnote 32 Throughout his life, he had felt a certain sense of homelessness, which he occasionally enjoyed, since it gave him the lightness necessary for travelling. In 1908, he had copied out this poem by Friedrich von Halm in his diary: ‘Without a house, without a motherland/ Without a wife, without a child/ Thus I whirl about, a straw/ In weather and wind.// Rising upwards and downwards/ Now there, and now here/ World, if you don’t call me/ Why called I for you?’Footnote 33 This was not only an age where Grand Tours expanded to exotic lands; new technologies also brought explorations upwards, into the sky.

Twenty years on and happily, though expensively, divorced from Hildegard née Duisburg, the heiress of Carl Duisberg, founder of IG Farben factory, Veltheim finally had found a home that could truly represent his character. Veltheim’s social circle from this time offers a glimpse into the world of elite sociability in Germany and Austria between the two world wars. His guests held a wide range of political views, from a militant opposition to the new republic to international socialism, and included an array of different professions, from artists, choreographers, and publishers to officers and diplomats. His guest book features entries by prominent German politicians, such as Paul Löbe, president of the Reichstag, General Wilhelm Groener, Reichswehr minister from 1928 to 1932, and Erich Koch-Weser, leader of the German Democratic Party (DDP). But what professional politicians like these had in common with his other, more Bohemian guests, had more to do with aesthetic taste than with agreement over political matters. Most of Veltheim’s guests were modernists in spirit; they experimented with new styles inspired by the ‘primitive’ cultures of Africa, Latin America, and the Far East. Many of them co-edited usually short-lived journals dedicated to literature, art, and political debate of a general kind, such as the character of Europe or the future of the world. Veltheim himself co-founded a publishing house, the Dreiländerverlag, with a base in Berlin, Zurich, and Vienna, in 1918, but was, unfortunately, forced to abandon it during the inflation.

In 1918, Veltheim had commissioned a new ex libris, designed by the Munich-based artist Gustav Schroeter, which illustrates the particular combination of modernity and esotericism in his thought.

It featured a Sphinx placed on an obelisk covered in symbolism which included a swastika. Sometimes called ‘sauvastika’ when facing left, as Veltheim’s version did, this symbol from Hindu mythology became fashionable in nineteenth-century esoteric circles, where it was associated with the goddess Kali and signified night and destruction. Russian Empress Alexandra Fedorovna (of Hessen-Darmstadt), who was immersed in the esoteric teachings of her age, had pencilled a left-facing swastika on the walls of Ipatiev house where the family spent its last days in Siberian exile.Footnote 34 The Sphinx was likely a reference to Oscar Wilde, one of the best-represented poets in Veltheim’s library, which was otherwise filled with works on mysticism, Orientalism, and anthroposophical writings.Footnote 35 Wilde’s poem The Sphinx, dedicated to his friend Marcel Schwob, a contemporary French surrealist whose own passion had been Edgar Allan Poe, resonated with Veltheim’s own symbolist influences: ‘In a dim corner of my room for longer than my fancy thinks/ A beautiful and silent Sphinx has watched me through the shifting gloom.’ Yet in the end, the Sphinx, as a fin de siècle Raven, turns out to be a deceptive guide, luring the onlooker away from his Christian faith to multiple secret passions. Veltheim’s fascination with Hindu symbolism reflected influences of German Orientalism of his time alongside Victorian Orientalism. In Veltheim’s ex libris, though, the Sphinx and the obelisk are merely providing a frame for another image, a view from a window onto a hot-air balloon rising up into a starry night, to reflect his passion for hot air ballooning.Footnote 36

Just over ten years later, his residence provided the architectural equivalent to his ex libris. Along with the estate, Veltheim had inherited the patronage of the local church of Ostrau. Veltheim embraced this traditional task of aristocratic patronage, but gave it his distinctive signature. In 1932, he ordered a new design of the patron’s private prayer room above the chapel, which was invisible to the congregation, with anthroposophical features. An architect who was also the designer of Rudolf Steiner’s Goetheanum installed an altar here, featuring Rosicrucian symbolism. Stained-glass windows in the anthroposophical style by Maria Strakosch-Giesler, an artist who had been influenced by Vasily Kandinsky’s synaesthetic theory of art, were also added. As a member of the Theosophical Society, Veltheim thereby performed a kind of hidden oecumenicism, a feature of his semi-public spiritual life, which was further augmented when he joined the Theotiskaner Order in 1935. As a proponent of cremation practices, which the Theosophical Society endorsed as a modernist cremation movement, Veltheim also commissioned the design of an urn in which his ashes were to be stored, and placed in the altar of the chapel.Footnote 37

Linking global mythology and contemporary modernist movements to his personal passions was characteristic not only of Veltheim’s personality, but of the particular syncretism which he actively sought in his social life. Veltheim liked to think of people he invited to his home as items in a unique collection. Unlike some of his friends of high nobility, like the Schulenburgs, he did not restrict himself to company of his social standing. He rather enjoyed the attention of people of all backgrounds, both social and geographical. This he learned from his travels around the world, which he began at a young age with the obligatory Grand Tour to Italy, and which eventually would lead him to Burma, Malaysia, India, Palestine and Egypt. From there, he not only brought artwork, Buddha statues, prints, shadow puppets and such like, but also, and more importantly, new friendships. For all his interest in foreign cultures, his steady circle of friends was mostly German-speaking. Alongside friends of high nobility such as Udo von Alvensleben, the art historian, Count Hermann Keyserling, the philosopher, and Constantin Cramer von Laue, who pursued a military career, the most significant group among his friends were poets, writers, and composers, such as the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, the existentialist novelist Hermann Kasack, the poet Thassilo von Scheffer, the artist Alastair, the Alsatian pacifist novelist Annette Kolb, the Georgian writer Grigol Robakidse, who was living in Germany since the Russian Revolution, and the composer Richard Strauß. Veltheim had met many of his friends during his studies in Munich were he attended lectures in art history. Among his favourites were Lucian Scherman’s lectures on Buddha and Buddhism, and a course on Persian art by Friedrich Wilhelm von Bissung. One photograph from 1931 shows him as the host of the world’s most renowned international spiritual celebrity, Jiddu Krishnamurti, at Ostrau [Fig. 17].

These were the German academics who continued the orientalist fashion that had begun in nineteenth-century German academia, with leading figures such as Indologist C.A. Lassen in Bonn or Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch in Göttingen.Footnote 38 Those who pursued related studies in Veltheim’s circle also attended courses by the ethno-psychologist Wilhelm Wundt in Leipzig and philosopher Henri Bergson in Paris. These Orientalists’ influence on their students was significant in later life; it was what provided a source of cohesion even where political agreement was lacking.

Figure 18 ‘Completed and restored’, plaque on the castle of Hans-Hasso von Veltheim (‘Completed and restored, 1929’), Ostrau, near Halle, Germany,

A related group of Veltheim’s friends were the publishers, Anton Kippenberg, head of Insel publishing house; Peter Suhrkamp; and Hinrich Springer. Other friends came to Veltheim through the Theosophical Society and its German branch, the Anthroposophical Society, of which he was a member. He knew the founder, Rudolf Steiner, quite well, and another prominent anthroposophist, Elisabeth von Thadden, was a cousin. Veltheim’s travels to India and China put him in touch with members of the new political elites there; he met Gandhi and in 1935, hosted one of his financiers, Seth Ambalal Sarabhai, the head of the Bank of India. The American dancers Ted Shawn and his wife Ruth St. Denis, founders of modern dance in the United States, were also among Veltheim’s regulars.

When the work on his ancestral estate was finished, in 1929, Veltheim placed a plaque above the entrance to his house, which read: ‘Completed and restored’. It was a paradox, of course: if it was only now completed, how could it be a restoration? The completion of the restoration came ten years after the first, radical generation of German republican politicians suggested expropriating all noble families in Germany, inspired by the Russian Revolution as a model. In this first wave of expropriations, some of Veltheim’s friends, including those who had their estates in the Baltic region, and members of the former ruling princely houses in Germany, such as Ernst Ludwig, Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt, lost all or significant parts of their estates. But all in all, the German land reforms of the 1920s had been minimal compared to those in some parts of eastern Europe.

Although nobles of high nobility who had inherited or were about to inherit large estates like Veltheim represented those social groups who were most threatened by the revolution, in the early 1920s they were still open to the changes these would bring to European culture. Indeed, the 1920s and early 1930s were years in which they could develop a number of projects as founders of educational and cultural institutions. Nobles who were based in Germany and Austria and who did not belong to the ruling princely families escaped the threats of expropriation that returned with Nazi legislation such as the Reichserbhofgesetz of 1933, with which the Nazis attempted to strengthen small-scale peasants at the expense of large landowners.

It was, indeed, not until 1945, in the Soviet part of divided Germany, that nobles who held estates in north-eastern Germany and what was now definitively Polish and Czechoslovak territory had to accept their expropriation as final. One day in October 1945, Veltheim received a call from Halle’s new mayor urging him to leave his ancestral estate within an hour.

Then I packed the barest necessities, before giving a call to the mayor to announce that I was now leaving the house – and once more, walked through my rooms and solemnly stepped down the large staircase, thinking that my great-great-grandfather Carl Christian Septimus von Veltheim (1751–1796) in 1785 […] had also walked down this same staircase with a heavy heart, before leaving Ostrau forever and going to St. Domingo, in the West Indies.Footnote 39

By the 1780s, Veltheim’s ancestor had gone bankrupt, and to avoid prosecution by his creditors, enlisted as a cavalry officer in the British Army. Suffering a common fate of the ‘Hessian’ regiments – German mercenaries hired by foreign army – he died in the West Indies of a fever and was never to see his family or his house again.

Veltheim’s own chosen place of exile was not the West Indies, but the northern German island of Föhr; here, he spent the remaining eleven years of his life preparing to write an autobiography, which contained numerous critical remarks of Europe’s violent, colonial past. Meanwhile, his old estate became the site of a polytechnic high school named after Nikolai Ostrovsky, the Russian socialist realist playwright from Ukraine who is best known for his autobiographical novel How They Forged the Steel, published in English translation by the Hogarth Press.

After 1990, the descendants of nobles like Veltheim began a laborious process of reclaiming what remained of their properties from the German, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Lithuanian, Estonian, and Russian governments. Many estates and castles throughout Germany and eastern Europe now remain public institutions: they have been turned into universities, recreational facilities, or museums of cultural heritage that are being rented out for weddings and other ceremonies.

Veltheim’s response was characteristic particularly of those nobles who by and large accepted their loss of former privileges, but saw their intellectual activities as a new source of cultural authority. The most obvious sense in which he displayed his adjustment to the loss of privileges is discernible from his production of narratives – in letters, diaries, in conversation, in memoirs, such as the letter to his mother, where he is moved when a worker treats him as an equal, despite looking like an aristocrat sounding like a ‘Dr. Phil’. At the same time, his insecurity concerning his status is confirmed by the opposing tendency to reconstruct nobleness by cultivating his estate, and fulfilling his duties of supporting his younger brother associated with his status as his father’s eldest son.

In addition to being allegories of old Europe and models for the genealogical and symbolic construction of identity, aristocratic intellectuals like Veltheim also developed a particular, elegiac way of thinking about their twentieth-century status as a type of homelessness. This homelessness, coupled with their earlier, poetic interests in Grand Tours and in being both detached from Europe as well as safely rooted in its deepest history, gave their cosmopolitanism a negative form. This became particularly pronounced by 1945, when nobles from East Prussia, East Germany, and the Habsburg lands had lost not only a rootedness in a particular region, which they had to give up incrementally throughout the revolutions of the earlier twentieth century, but also, the very possibility of belonging to several European regions at once. Many memoirs of nobles from this period combine the general trope of homelessness and loss with an idea of belonging to Europe as a whole and embodying its past culture. Among the most representative figures of ‘noble homelessness’ in German thought after 1945 was the work of the social democrat Marion Countess Dönhoff, who, after her flight (on horseback) from East Prussia, embarked on a career as one of West Germany’s most prominent journalists.Footnote 40 She became the founding editor of the weekly newspaper Die Zeit. Another nobleman who defined himself as an expellee from eastern Europe, as ‘Europe’s pilgrim’, was Prince Karl Anton Rohan.Footnote 41 In the 1920s and early 1930s, he was the founding editor of the journal Europäische Revue. In 1945, his family lost the estates in Czechoslovakia, and Rohan was forced to work on his own estate as a gardener and then to spend one and a half years as an American prisoner of war; his reflections on Europe’s history, which he published in 1954, bore the title Heimat Europa.Footnote 42 Rohan’s fellow Bohemian Alfons Clary-Aldringen published his memoirs under a similar title, A European Past.Footnote 43

In the eyes of Prince Rohan and the contributors to his journal, Europe in the 1920s was facing a struggle between past and future. The European past was characterized by complexity regulated through a strict social hierarchy. In this structure, empires persisted not only thanks to formal institutions of power but also, and crucially, informally, because everyone knew in each situation how to behave appropriate to their rank or status. By contrast, in the age of modernity, those expectations were no longer clear. He could have made this point by speaking about institutional change or radical politics in the street, but his preferred example was social dance:

There is a higher meaning in the tradition that those in power […] do not dance with people, or, what is even more important, do not dance in front of people who are not of the same social standing. Today, you can see in any dance café people of high nobility, duchesses, wives of the large industrial and financial magnates, even girls of the underworld entwined in Charleston with their legs, arms, and other body parts, swinging amongst other unknown people to Negro rhythms. And at the same time, those in power in Europe attend meetings with rumpled hats and trousers. The dance of political representation has disappeared, to be replaced by the wacky body parts wobbling in Negro chaos.Footnote 44

This passage highlights the extent to which thinking in terms of race, social status, as well as aesthetic taste became entangled in the 1920s. The threats of modernity for members of Europe’s old elites such as Rohan were multiple. But this passage highlights that they were essentially reducible to two points: an erosion of hierarchy, and an erosion of identity, continental, racial, and sexual. Not all responses to these threats of modernity were pure rejections. In fact, Rohan himself was particularly attracted to aspects of a modernist aesthetic and innovations in the theatre and literature. While deeply committed to Vienna at an emotional level, after the war, Rohan had settled in Berlin and made German political circles the central sphere of his own activity as an intellectual.

The quest for new spiritual as well as new sexual identities was another prominent element in interwar aristocratic intellectual circles. Both themes, the interest in oecumenical and non-Western spirituality and the Orient, and the openness towards non-conventional sexualities, were prominent in the work of aristocratic intellectuals and the circles they supported. Just as the Habsburgs had found a way of making signs of stigma into distinction, intellectuals like Keyserling made their ironic anti-nationalism into a Brahmanic quality rather than that of a pariah.

Double Orientalism: celebrity princes in the Soviet Union and India

The aristocratic mediators like Veltheim joined a generation of new global travellers who were interested to discover alternative civilizations in India and the Soviet Union. During an extended trip to India from December 1937 until August 1938, Veltheim was in Calcutta as an informal delegate of the German Reich and official guest of the Indian government. Among his hosts was Lord Brabourne, then Viceroy of India and Governor of Bengal. A conversation between the two, which the Viceroy declared as a ‘private and personal’ encounter between two aristocrats and old officers’, revealed that they had likely ‘faced each other’ at the battle of Ypres.Footnote 45 Throughout this trip, Veltheim was expected to deliver public lectures and gauge private opinion from a variety of influential personalities in India, on which he reported in extended form in typescripts that were sent back to Germany, to be read by officials, as well as a group of close friends.Footnote 46 In the typescript itself, Veltheim avoided stating his opinion on the German regime directly, however, his rendering of critical questions thrown at him on occasions such as in the immediate aftermath of the Night of Broken Glass, 9 November 1938, makes it sufficiently plain that his own attitude to the regime was critical. This became more pronounced in the revised version of his Indian travel ‘diaries’, which was first published in 1954. Thus, in said conversation with Lord Brabourne, Veltheim claims to have called Hitler a dictator who would not shy away from a war. Brabourne, by contrast, emphasized Hitler’s ‘immediate experience of the front’ as a simple soldier, unlike officers such as themselves; because of this proximity to the front line, Brabourne thought Hitler would not ‘expose the German people to a war’.Footnote 47 At the same time, the typescript suggests that on other occasions, Veltheim defended the German regime from ‘false’ allegations, such as the assumption, which he often encountered in the company of Brahmins and Maharajahs, that the Nazi government expropriated large landowners. ‘Nothing could be further from the truth’, Veltheim assured his conversation partners, signalling to his readers that it was important to keep conversation with his aristocratic ‘peers’ in India in order to prevent them from having false views of Germany.

In addition to India, in the 1920s, many eyes turned to the Soviet Union as an alternative type of civilization: would it remain true to its radical premise and rule out traditional ranks and privileges from the army and other institutions? In 1927, Rohan went on a trip of the Soviet Union, primarily, Moscow and Leningrad, following an invitation from VOKS, the Soviet cultural organization for foreign relations. As he put it in his travelogue, he went to Russia as a Gentleman would go to the land of the Bolsheviks.Footnote 48 For people of his social circle, the Land of the Bolsheviks was another social and cultural system that posed a threat to Europe’s former self.

However, the most famous project of a small court revival had been inspired by an example from India. It belonged to a philosopher from the Baltic region who initially had little to do with the smaller courts. Count Keyserling came from the Baltic region of the Russian Empire, and his wife was the granddaughter of Prussian Iron chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Yet personal connections meant that he was on good terms with the Grand Duke of Hessen Darmstadt, whose artists’ colony he proceeded to reinvigorate with a new concept.

Keyserling wrote in a letter to Kessler ‘strictly confidentially’ that he was about to found a ‘philosophical colony’ with himself ‘at its centre’. Its success would be ‘guaranteed since the Grand Duke of Hesse presides over it’. Keyserling believed that this school would bring about ‘something of importance’ because ‘all that was ever significant in Germany always began and will emerge only beyond the boundaries of the state’.Footnote 49 The foundation did not do entirely without political support, however, even if it was the support of a politician who had only just lost the power over his state: Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hessen-Darmstadt, Queen Victoria’s grandson, a cousin of Wilhelm II of Germany, and brother-in-law of the recently assassinated Nicolas II of Russia, had been deposed along with the remaining ruling princes on 9 November 1918.

In seeking to support Keyserling’s project, Ernst Ludwig drew on his prior project of aesthetic education. In 1899, his knowledge of the British Arts and Crafts movement of Ruskin and Macintosh had inspired him to found an artists’ colony in an area of Darmstadt called Mathildenhöhe, which persisted until the outbreak of the First World War. Its aim was to create a union between ‘art and life, artists and the people’, through a joint project of aesthetic reform through art nouveau. It eventually came to be organized in four exhibitions held between 1901 and 1914, which showcased German exponents of art nouveau. The innovative character of this colony was that it combined relatively new ideas of reform socialism, who envisaged art as a form of craft labour and introduced new concepts of living like ‘garden cities’ to the public imagination, with the older tradition of aristocratic patronage for artists. Ernst Ludwig’s project became influential in German circles of aesthetic resistance to the bombastic masculinity of Wilhelm II.

The focus of the School of Wisdom was from the start less patriotic and more universalist in spirit. This expressed not only Keyserling’s newly acquired knowledge of Oriental culture, but also Ernst Ludwig’s more recent interest in ecumenical thought, which he displayed in his book Easter. A Mystery (Leipzig: Kurt Wolff, 1917), published under the pseudonym K. Ludhart. As such, it became an internationally renowned centre for cultural critics, mystics, psychoanalysts and Orientalists. By 1921 Keyserling’s academy had some 600 permanent members and held three annual conferences. The rabbi and philosopher Leo Baeck, the philosopher Max Scheler, the psychoanalyst C.G. Jung, and the historian Ernst Troeltsch were among its participants. The academy functioned through membership lists and conferences, which took place regularly between 1920 and 1927, with one follow-up conference in 1930. Thereafter the academy turned into a virtual association through which members could obtain information about new books and borrow books from Keyserling’s vast library collection. One of his most intensive contacts was Karl Anton Rohan, the director of the Austrian branch of the Union Intellectuelle Française (Kulturbund) in Vienna. His association sought to promote peace in Europe through publications (for example, German–French co-editions) and other cultural activities. Keyserling’s early mentors included French philosopher Henri Bergson and the German philosopher (and later National Socialist ideologist) Houston Stewart Chamberlain (with whom Keyserling fell out even before the First World War). Thomas Mann’s diaries abound in entries confirming his appreciation of Keyserling’s works.Footnote 50

Keyserling and his wife devoted the greatest part of their time to the management of his public appearance. Keyserling remained prolific throughout this period, publishing fourteen books between 1906 and 1945, though a number of his works are without doubt repetitive. In his thought he was strongly influenced by C.G. Jung’s and other psychoanalytic theories. Together with a psychoanalyst, Erwin Rousselle, Keyserling organized meditation sessions and even experimented with occult phenomena (only so as to question them, as he argued in a book). Among such experiments he invited a miracle healer from northern Germany to test his abilities in a Darmstadt hospital.

Keyserling’s school can be located within a larger circle of private educational reform associations positioned between cultural sceptics, neo-religious and reform movements of the post-First World War period, such as the Eranos group, or the anthroposophical school around Rudolf Steiner.Footnote 51 Its closest analogue in many ways was the Theosophical Society, founded by the ‘clairvoyant’ Helena Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott in New York. Like Keyserling, Helena von Hahn, or Madame Blavatsky, as she came to be known, came from Baltic German nobility as well as an old Russian lineage, the Dolgorukii family.Footnote 52 Unusually for women of her standing, she escaped the family ties of both her own and her husband’s family and embarked on a life of global travel, which took her from Constantinople to America, as well as travels in the Middle East, the Mediterranean, Nepal and India. She used her gifts of eloquence and invention to become a spiritual leader to Western enthusiasts in the East. When in the United States, she encountered the former Civil War military officer Olcott, who had actually undertaken to expose new occultist leanings in America. Born in New Jersey, he was a Presbyterian farmer and expert in agriculture who had once been invited to take the chair of scientific agriculture in Athens but instead became a journalist before joining the Civil War with the Union army. It was as a journalist reporting on the occult that he became persuaded by Blavatsky’s skills as a seer, and eventually the two formed a movement called the Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 in Adyar, Madras (now Chennai), India. Between 1886 and 1908, the society quickly spread, opening chapters in America, New Zealand, Australia, and several European countries, including England, France, and Russia. By 1896, its declared goals were a ‘universal brotherhood without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or colour’, a comparative approach to religion, philosophy, and science, and the belief in ‘powers latent in men’ that could be recovered.Footnote 53 Among the most prominent European members of the society was Rudolf Steiner, who, having opened the German chapter, eventually split off from the society and became the founder of his own, the Anthroposophical Society. In Britain, a number of Fabian socialists and other prominent intellectuals were members of the society. In the United States, Unitarian architect Frank Lloyd Wright was close to the society along with his wife, the dancer Olgivanna (Olga Ivanovna Hinzenburg, of Montenegrin nobility). Throughout its years in existence, the society recruited more members who were considered gurus, such as Jiddu Krishnamurti, who was educated to become a guru from an early age, but eventually also split away from the society. Other figures of similar status, such as the gurus Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, had respect for the theosophists but never joined them.

The similarities between Keyserling’s project and that of the theosophists transpire at multiple levels. Keyserling was a great supporter of Besant, whom he met during his world tour in India in 1914, and many of his guests were theosophists. Intellectually, the influence of the theosophists was visible in his attempts to lead joint meditation sessions and to seek the participation of representatives of all world faiths. Practically, just as in theosophy, the figure of Keyserling himself as a leader whose ‘conversion narrative’ becomes a leading paradigm for attracting followers, was important for the school. Finally, just as the theosophists, the school sought to have an influence on modern society at a metapolitical level, with a particular interest in a comparative view of cultural peculiarities in different states. Annie Besant had been an active supporter of Gandhi’s Home Rule and Indian independence. In Russia, prominent theosophists included Russian poets and thinkers who fled the revolution or were hostile towards it, defending idiosyncratic conceptions of Slavic and Orthodox identity, people such as the poet Andrei Belyi, Aleksandr Blok, the philosophers Vladimir Soloviev and Nikolai Berdyaev, and the composer Alexander Skriabin. In Britain, many Fabians, as well as novelists such as Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood, the poets W.B. Yeats, W.H. Auden, were members. In the United States, the inventor of the lightbulb, Thomas Edison, was among its members. A prominent Dutch member was the artist Piet Mondrian.

All these individuals subscribed to the theosophists’ manifesto of seeking to recover the ‘powers latent in man’ under the belief in the fundamental equality of people of all creeds and races. Although not a majority of theosophists and related mystics were of aristocratic background, aristocrats were important in many cases as hosts of conferences and facilitators of encounters between different theosophists. For example, neither Rudolf Steiner nor Gourdjieff were of aristocratic background. Yet association with aristocrats was an important vehicle to gain wide social support.Footnote 54 Thus a Dutch nobleman had lent his castle to Krishnamurti, Castle Eerde, which belonged to Baron Philip van Pallandt, in 1921.

In founding a separate school that was inspired by, yet not incorporated into, the Theosophical Society proper, Keyserling pursued several goals. First, he wanted to use the conferences to assess the present situation of European politics specifically, rather than universal human culture. Secondly, he wanted to ‘create a new, higher culture from our current internal collapse’. Looking explicitly beyond the differences between ‘races, parties and faiths’, the aim was to instil in his students an ‘atmosphere of high culture’.Footnote 55 Politically, he wanted to emphasise the importance of aristocratic and intellectual leadership in overcoming this process of decline; and to learn from other cultures in preparing for a future transformation in the hand of aristocratic sages. In this sense, the School constituted, as Suzanne Marchand put it, a ‘breathtaking’ break from its humanist foundations, which rested on the superiority of Western civilization’s Greek roots.Footnote 56 It was not just a break from humanism, but above all a radically different project from that of bourgeois intellectuals. After the over-democratised state it was in now, Keyserling concluded, the future belonged to a ‘supranational European idea’, which would overcome the extreme democracy of America and Russian Bolshevism.Footnote 57

The place of Germanic culture in the genealogy of European memory

After the Second World War, the idea of two opposing German traditions of Europe, one, a benign federation of principalities, another, a malignant national empire-state, remained an influential paradigm of international thought in the twentieth century. But it was the work of individual celebrity aristocrats like Keyserling that had kept it particularly alive in the minds of the European elite in the 1930s.Footnote 58 Only a reformed aristocracy could offer such a structure.Footnote 59 Keyserling argued that Europe, which was currently in a period of historical decline and overtaken by many rival civilizations, would again reach a historic high in the future. Germany and Austria, fused in an ideal ‘chord of Vienna-Potsdam-Weimar’, would play the greatest role in bringing about this new constellation – not as a pan-German state, however, but as the heart of a new Holy Roman Empire. He demanded a leading role for Germany in a future European state, because the ‘representatives of German culture’ have displayed the least attachment to the ‘idea of a nation-state’. Instead, they were more at home with the notions of a ‘tribe or a party’ than that of ‘peoplehood’, just as in the times of Arminius as Tacitus has described it.Footnote 60 The future, Keyserling argued in later works, would bring about a ‘Pan-European, if not a universal Western solidarity the like of which has not existed since the Middle Ages’. As he put it in a manuscript version of a public lecture to be given at the Salle Pleyel in 1937, which Nazi authorities prevented him from attending, the role of the intellectuals was to ‘anticipate the best possible future on the basis of fulfilled Destiny’.Footnote 61

As he put it in 1937, for ‘the foundation of the new aristocracy of his dreams, Nietzsche hoped for a preceding era of socialist convulsions; and at this very moment we are passing through it’. In this double sense of an emotional superiority and an overcoming of bourgeois narrowmindedness, Keyserling published an article advocating socialism as a necessary ‘basis’, perhaps also a necessary evil, for the transition to a future aristocratic politics.Footnote 62 In this respect, Keyserling appropriated the prominent discourse on a ‘new nobility’, which was common to the elite circles of German and Austrian sociability in the interwar years, albeit by infusing it with theoretical reflections on his own life.Footnote 63 Despite Keyserling’s emphasis on renewal, however, his School was also an enactment of the old, pre-revolutionary order in which the Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig appeared in his function as a patron of art and culture.

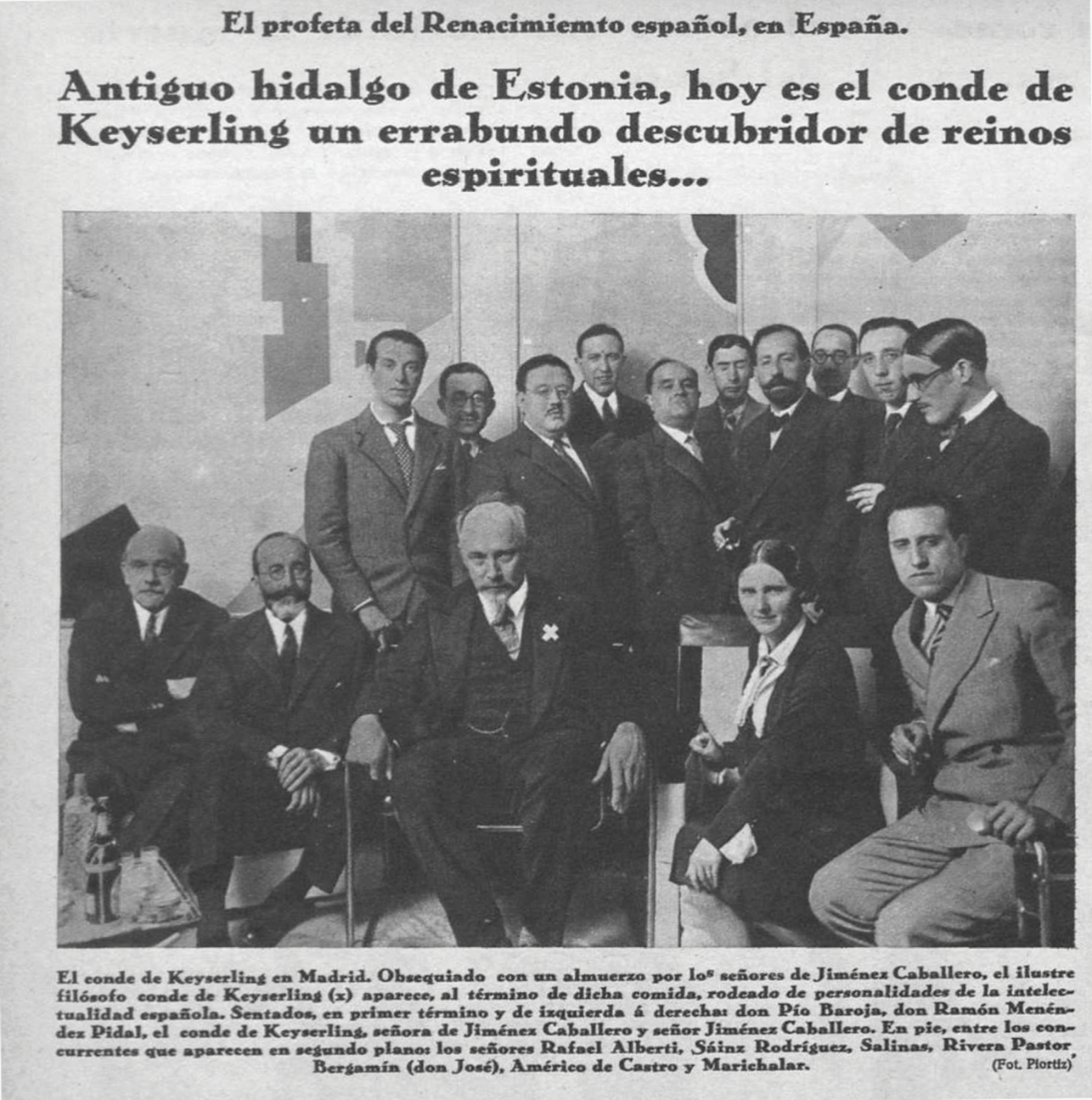

A central part of Keyserling’s project was his cultivation of a vast and international social network through which his project of aristocratic renewal was propagated and developed. On his international lecture tours, he was celebrated as an ‘ex-hidalgo’ who turned his expropriation into a new form of spirituality. Keyserling’s Spanish audiences placed him at the same time on the same plane as Don Quixote and as a specifically Germanic import product. ‘Antiguo hidalgo de Estonia, hoy es el conde de Keyserling un errabundo descubridor de reinos espirituales’, read one of the articles covering Keyserling’s visit to Spain in 1929 [Fig. 19].Footnote 64 For his English and French readers, by contrast, Keyserling becomes more a symbol of restlessness and a wandering elitism.Footnote 65

Figure 19 Juan G. Olmedilla, ‘Antiguo hidalgo de Estonia, hoy es el conde de Keyserling un errabundo descubridor de reinos espirituales …’, in: Cronica, 11 May 1930, 2

Following his trip to South America in 1929, he published his South American Meditations, which Carl Gustav Jung praised as ‘a new and contemporary style of “sentimental journey”’, and in another instance he characterized Keyserling as ‘the mouthpiece of the Zeitgeist’.Footnote 66 Not least due to the personal connections to the influential literary editor Victoria Ocampo, Keyserling’s work found wide, albeit critical, reception among Spanish-speaking, particularly among Argentinian, readers such as Eduardo Mallea and Jorge Luis Borges.Footnote 67

His School of Wisdom, which persisted until 1937, was partially financed through its summer conferences and membership lists, which were managed through subscriptions to two journals associated with the School: Der Leuchter, and Der Weg zur Vollendung. Informal networks were to provide an alternative to official collaborations, since Keyserling was willing to ‘collaborate with all parties’ who wanted to come to his ‘centre of influence’. The purpose was to ‘form a new human type, who is the bearer of the future’.Footnote 68 Keyserling argued that his School was designed to become a ‘movement’ whose ‘economic substructure is the Society of Free Philosophy’. Footnote 69 It ‘addresses itself not to philosophers only, but rather to men of actions, and is resorted to by such’.Footnote 70 As one reviewer commented,

The community of Keyserling’s pupils is being united by his publications. […] From the impulse of Count Keyserling’s personality – this is the firm goal of the Society for Free Philosophy – there will arise a circle of men and women in all of Germany which will smoothen the path towards the eternal goods of life for our people.Footnote 71

The political goals of Keyserling’s School were threefold: to assess the present situation of European politics as a decline into anarchy and mass culture, a period of radical and socialist ideas which had to be accepted; to emphasise the importance of aristocratic and intellectual leadership in overcoming this process of decline; and to learn from other cultures in preparing for a future transformation in the hand of aristocratic sages. In this sense, the School constituted a sharp break from its humanist foundations, which rested on the superiority of Western civilization’s Greek roots. It was not just a break from humanism, but above all a radically different project from that of bourgeois intellectuals. After the over-democratized state it was in now, Keyserling concluded, the future belonged to a ‘supranational European idea’, which would overcome the extreme democracy of America and Russian Bolshevism.Footnote 72 His Baltic correspondence partner, the historian Otto von Taube, agreed that the princely attitude of being rooted to a region and simultaneously standing ‘above nations’, could serve as a model for the future of European regeneration.Footnote 73

As Rom Landau recalled Tagore’s visit in 1921, hosted by the former Grand Duke of Hesse Ernst Ludwig:

After tea we went into the neighbouring fields, and grouped ourselves on the slope of a hill, on the top of which stood Keyserling and Tagore. […] The Indian poet was wearing long silk robes, and the wind played with his white hair and his long beard. He began to recite some of his poems in English. Though the majority of the listeners hardly understood more than a few words – it was only a few years after the war, and the knowledge of English was still very limited – the flush on their cheeks showed that the presence of the poet from the East represented to them the climax of the whole week. There was music in Tagore’s voice, and it was a pleasure to listen to the Eastern melody in the words. The hill and the fields, the poet, the Grand Duke and the many royal and imperial princes, Keyserling and all the philosophers and philistines were bathed in the glow of the evening sun.Footnote 74

Keyserling’s own intentions to learn from Tagore for European renewal had hit a nerve among his post-war audiences.Footnote 75 Among the most important influences on his work was the Academy at Santiniketan (today known as Visva-Bharati University), founded in 1921 by the Bengali writer and poet Rabindranath Tagore on the location of his father’s ashram. Keyserling had first met Tagore, twelve years his senior, during the Indian part of his world tour, in 1912, when he stayed at Tagore’s house in Calcutta, then again in London in 1913, and soon after the foundation of the Darmstadt School, in 1921, he invited Tagore on a lecture tour of Germany. Both men had taken similar roles upon themselves, even though Tagore’s fame surpassed that of Keyserling by far after Tagore won the Nobel Prize in 1913. Both were of noble origin but also critical of the ossification of nobility; both were in some sense nationalists but at the same time considered their mission to be reaching humanity at large, and therefore travelled the world to give public lectures and, not least, receive financial backing for their educational institutions; both also took some inspiration from another Count, Leo Tolstoy, whose revolutionary peasant communities in Russia also inspired movements in South Africa. Moreover, like Keyserling, Tagore had been impressed by Victoria Ocampo’s cosmopolitan cultural patronage in Argentina, where he too stayed as an honorary guest.Footnote 76

Inspired by Tagore, Keyserling positioned himself as bridging East and West. His intention was to turn the position of Europe between the two into an advantage, and criticise the old aristocratic system without rejecting it entirely.Footnote 77 Even though he shared some premises with other elitist educational programmes of the period, Keyserling’s Orientalist School differed markedly from the neo-classical background of other contemporaries. For instance, the classicist Werner Jaeger decried in 1925 that while ‘in Beijing Rabindranath Tagore proclaims the reawakening of Asia’s soul to the gathered crowd of yellow-skinned students, we, tired from the World War and the crisis of culture, are staring at the fashionable theory of the Decline of the West’.Footnote 78 Keyserling’s School proposed an entirely different use of the comparative shift in cultural criticism by bringing Tagore to a gathering of the Darmstadt crowds and selected participants of his School at the princely palace.

Keyserling was particularly interested in proving that different cultures have always been associated with aristocracies. In his book reviews of ‘oriental’ cultural critics, therefore, he reserved critical positions, such as the views of Tagore himself, to footnotes, in which he commented on Tagore’s remark that Indian culture had been shaped by the Kshattryas, not the Brahmins, merely as ‘interesting’.Footnote 79 With regard to the more radical movement of Mahatma Gandhi, he expressly described him as a ‘reactionary’, because in ‘sympathising with the false progressivism of modernization he denied Indian culture’.Footnote 80

Another interest of Keyserling’s in comparing his contemporary ‘post-war’ Europe with other cultures, was his desire to relativize the impression cultivated by many Germans that Germany had been mistreated the most by the post-war political settlements. Other countries, Keyserling argued, had suffered an even more catastrophic decline, drawing attention to Turkey. Nonetheless, as he put it, it was due to this imperial decline that countries like Turkey or Germany would be able to recreate a new European order, as the Turkish intellectual Halidé Edib wrote in a book which she sent to Keyserling with a dedication.Footnote 81

As one of Keyserling’s followers, Prince Karl Anton Rohan wrote in his book Europe, first published in 1923, the old ‘nobility’ now had the task ‘to transform the old values in a conservative way, according to its tradition, using the new impulses of the revolution’. Unlike the class struggle that motivates the Bolshevik conception of the revolution, he thought, the goal of this one was the creation of a ‘unified Europe’ instead of an ‘ideological brotherhood of mankind’.Footnote 82 Count Keyserling, in his correspondence with Rohan, engaged in theorizing the new status of the nobility further. He described to him that he was also, ‘under conditions of utmost secrecy’, working on a ‘vision for all the peoples of Europe’.Footnote 83

Keyserling also promoted his School by lecturing abroad. Such lectures were paid and frequently guaranteed him his income, and they were organized by professional concert agencies.Footnote 84 He corresponded with scholars interested in his work and actively invited them to visit his School. Among those who paid attention to the project was the Flemish socialist and in later years Nazi collaborationist Hendrik de Man, who taught at Frankfurt University in the early 1920s, and became interested in Keyserling’s project. He classified him as one of ‘Germany’s New Prophets’, a generation inspired by Nietzsche’s role as a philosopher lecturing to his contemporaries while also addressing a future humanity.Footnote 85 These three thinkers identified by de Man – Keyserling, Oswald Spengler, and the philosopher of fiction, Hans Vaihinger, – had also received the Nietzsche Prize of the Weimar Nietzsche Society in 1919. De Man was surprised that ‘K. the aristocrat’ was ‘a democrat’, while ‘Sp. the plebeian Oberlehrer – a monarchist’ and a ‘worshipper of aristocracy’ – this to him was a ‘a vindication of the psycho-analytic theory of “compensations”!’Footnote 86 For de Man’s own elitist vision of socialism, Keyserling’s work was of central importance.

Keyserling’s influence on like-minded younger intellectuals such as Prince Karl Anton Rohan had not only intellectual, but also institutional significance. Rohan founded two institutions in the spirit of Keyserling’s School: the literary and political journal Europäische Revue, and the Kulturbund, a Viennese branch of the Paris-based Institut international de cooperation intellectuelle. While the Revue eventually succumbed to Nazi propaganda efforts and eventually ceased publication during the War, the Institut became the institutional progenitor of UNESCO after the Second World War. Keyserling encouraged Rohan ‘under conditions of utmost secrecy’ to work with him on a ‘vision for all the peoples of Europe’.Footnote 87 Specifically, he sought to encourage Rohan to use his private circle of ‘friends’ for studying the ‘problem of nobility’ under his ‘guidance’, which was supposed to contribute a chapter on ‘Germany’s Task in the World’ to a forthcoming publication on Germany and France to be edited by the Prince.Footnote 88 In the proposal for an edited book on Germany and France, Rohan lined up not only well-known historians and legal theorists like the German nationalist historian Hermann Oncken and the constitutional theorist Carl Schmitt, but also now forgotten German and French authors who fall into the suggested category of aristocratic writers. They included names such as Wladimir d’Ormesson, Alfred Fabre-Luce, Henry de Montherlant, or Knight Heinrich von Srbik. Keyserling, in turn, also used Rohan’s network of relatives and acquaintances among the German-speaking Habsburg nobles in Bohemia to promote his own work. In this connection, he approached Rohan’s elder brother Prince Alain as well as members of the oldest Austro-Bohemian noble families like ‘Count Erwein Nostitz’, ‘Count Karl Waldstein’, ‘Count Feri Kinsky, Countess Ida Schwarzenberg, Count Coudenhove’, ‘Senator Count Eugen Ledebur’, and other, exclusively noble, families that he wanted to win over as ‘donors’ for his own project of a ‘School of Wisdom’ for the creation of future European leaders.Footnote 89

I was not born in Germany but in Russian Estonia. Only in 1918, when Bolshevism robbed me of all I had inherited [alles Ererbte], I moved to Germany and found a refuge here, a new circle of influence and a new home; … Since 1918 I have therefore considered it my duty of honour and obvious duty and burden to serve Germany’s prestige wherever I could. […] I hope to be able to contribute to Germany especially today thanks to my special constitution.Footnote 90

The aristocrat as an anti-fascist

During a conference on the future of Europe, which the Union for Intellectual Cooperation had convened in Europe, Keyserling arrived as Germany’s representative.Footnote 91 Aldous Huxley, Paul Valéry, and numerous other famous European public intellectuals were also present. Thomas Mann, who was soon to leave Germany for his first place of exile (and one that attracted most of Germany’s best known writers and intellectuals) in Sanary-sur-mer, had cancelled his participation at short notice. Before travelling to Paris, Keyserling, by contrast, sent a letter to the propaganda ministry, addressed to Goebbels personally, asking for permission to travel. He secured it by promising to report on the meetings. In a letter dated 20 September 1933 and addressed to the ‘Reichsminister für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda’, Keyserling, on the one hand, emphasised that he participated at the congress ‘only as a personality, not as a representative of Germany’ [nur als Persönlichkeit, nicht als Vertreter Deutschlands]; on the other hand, he used the opportunity to assert his essentially positive attitude to National Socialism as a movement, which he dated back to the year 1918, when he belonged ‘to the first who had predicted and promoted a new art of socialism as a future form of life for Germany’, drawing his attention to his publication on ‘Socialism as a universal foundation of life’ of 26 November 1918.Footnote 92

Keyserling held that ‘politics is never the primary cause, but only the execution of popular will’, regardless of whether formally the government is a ‘democracy or a tyranny’. Footnote 93 Locating Europe between two ‘collective primitivisms’, the Russian and the American, and ‘fanatic’ movements – Bolshevism, Marxism, and Hitlerism – Keyserling sketched the possible future of European identity as an essentially intellectual one. It all depends on a superior type of human being, a European who is beyond the above movements, who has not yet been born, in short, ‘un type d’Européen supérieur’. The old elites, to which Keyserling counted himself, would have to recognize their lack of worth due to the lack of applicability of their ideas. The men of the future would incorporate both ancient and modern culture and will be able to aspire for a common life disregarding the differences.

In this context, Keyserling’s own position gestured towards a voluntary identification with the Jews, a posture with which he provoked his social circle. Voluntarily identifying with the Jews, or having his books translated by writers in Yiddish, as Keyserling did, was a form of ‘going native’ under conditions of elite precarity. In a strange way, this tendency to compare Jewish and aristocratic identity echoed the discourse on aristocracy and the Jews in Nazi propaganda. One caricature from a Nazi satirical magazine compared the Jew and the Baron in their status as enemies of the (Aryan) state [Fig. 20].

Figure 20 ‘Enemies of the state in each other’s company’, in: Die Brennessel, 5:36 (10 September 1935). BA R 43 II 1554–5, 61ff.

‘What do you say about our times, Levi,’ the nobleman asks the Jew. ‘Oh, don’t try to talk to me, Herr Baron. I don’t want to be compromised by your company.’ The image displays only one of many examples of efforts within parts of the National Socialist movement to oust nobles from the new Germany, and was sent to the Reich chancery as part of a series of complaints made by the German Nobles’ Union about affronts against the status of the nobility in Nazi newspapers.Footnote 94

One of Keyserling’s relatives, another Baltic German, had become a ‘Siberian and Mongolian condottiere’.Footnote 95 Roman Ungern-Sternberg (1886–1921) served as a self-proclaimed dictator of Mongolia during the Russian Civil War in 1921, which he entered as a member of the White Army but continued as an independent warlord. He wanted to restore not only the Khanate in Mongolia, but also the Russian monarchy, and came to fame as a ruthless anti-Semite and persecutor of communists.Footnote 96 He was tried and executed by the Red Army, however. Keyserling emphasized some positive qualities of the ‘Mad Baron’. His biographers, Keyserling thought, presented him in a one-sided light. In fact, his relative was ‘no Baltic reactionary, but the precursor of new Mongolian greatness, which continues to live on in the songs and tales of the steppe.’Footnote 97 Moreover, Roman, in his eyes, was characterized by an extraordinary ‘Delicadeza’ – the typical softness of brutal men, which he had discerned in South American culture as the kernel for a new renaissance.Footnote 98

These different cultural comparisons Keyserling drew on were all united by a common theme – the need for aristocratic leadership for political renewal which, Keyserling hoped, also awaited Europe. But there was one further, intellectual component to this new aristocracy, which Keyserling himself wanted to cultivate with his School.

In his role as a global thinker, Keyserling joined the anti-fascist intelligentsia which gathered in Paris in the mid-1930s and comprised mostly liberal writers and public figures. In his lecture on ‘La Révolte des forces telluriques et la responsabilité de l’Esprit’, delivered on 16 October 1933, Keyserling positioned himself as a fatalist.Footnote 99 These intellectuals have to show understanding for these telluric forces and they can ‘preempt the event, anticipate the best possible future on the basis of a fulfilled Destiny’.Footnote 100 All the historical phenomena, which Keyserling classified as essentially telluric – Bolshevism, National Socialism, and Fascism – ‘have to be accepted, for no reasoning will change them’.Footnote 101

Only two years later, Keyserling would warn Kessler in a personal conversation that he should never return to Germany for ‘anti-Semitism and the [National Socialist] movement are getting more virulent every day’ and that with support from the ‘majority of the population’.Footnote 102 By 1939, Keyserling was in internal exile in Germany and would only be allowed to leave Germany during the allied bomb raids thanks to the interference of his publisher Peter Diederichs.

Orientalism and cosmopolitanism

Aristocratic modernists like Veltheim and Keyserling played a key role as go-betweens between Europeans and non-Europeans. In this, they formed part of a longer tradition of German Orientalism as it had formed in the period leading up to the First World War.Footnote 103 The twentieth-century lives of some of these Germanic Orientalists suggest a further nuance to the history of international culture between the decline of Europe’s empires and the rise of National Socialism. It was their shared status as derecognized, formerly voluntarily, now involuntarily, rootless European subjects that allowed this generation of German aristocrat-intellectuals to assume an ambivalent role as forgers of a new, global elite. At the same time, the case of Keyserling also demonstrates how this ideal became increasingly compromised, as aristocratic character-builders like Keyserling came to various arrangements with the Nazi regime, or tried to associate themselves with the cultural internationalism of large interstate organizations such as the League of Nations. In this sense, the path from the princely courts into the twentieth century leads to such institutions as UNESCO, and to transnational spiritual elite communities such as the Theosophical Society.