Introduction

In China, where there is a strong tradition emphasising filial piety, informal eldercare is ubiquitous. Because of this, and the less-developed nature of the formal eldercare system, it is easy to make a distinction between formal and informal care in China. Informal eldercare is provided by family members, whereas formal eldercare represents the elderly services provided by central or local government. Informal eldercare is usually defined as care provided by family members, especially by daughters and daughters-in-law.Footnote 1

Informal eldercare, along with household tasks and childcare, is seen as women's work within the household. To understand informal eldercare in China, one must revisit gender ideology and attitudes to domestic work, which is usually performed by women. The following paragraphs briefly introduce the background of shifts in gender ideology since China's entry into the post-socialist era, which has exerted a great influence on Chinese women's eldercare provision in the 1990s and the early 21st century.

In the Maoist era (1949–1976), the socialist state's solution to promoting gender equality was to mobilise as many women as possible into productive fields, and thus to achieve economic independence. Nearly all women were mobilised to take a job outside the household. This gender ideology did not challenge the traditional gendered boundaries, however. Instead, it has been frequently shown that under the ‘female labour model’ (nü lao mo, an ideal model of female worker) of the Maoist era, women still strove to meet the traditional standards of womanhood (Entwisle and Henderson, Reference Entwisle and Henderson2000). That is, they took charge of domestic work.

With Mao's death in 1976, and the ideological shift from a collectivist to a market-oriented economy, there was a shift in gender discourse from state feminism, which embraced women's participation in production, to a post-socialist feminism. Long-held beliefs about ‘appropriate’ gender divisions – ‘men outside the home and women inside the home’ – were revived. Thus, it is still assumed that domestic work is women's work (Jacka, Reference Jacka1990), suggesting that the separate spheres model for traditional gender roles has been embraced once again. Some studies have found that there is a marked withdrawal from the state's empowerment of women, a resurgence of patriarchal values and a return to traditional gender roles (Summerfield, Reference Summerfield1994; Berik et al., Reference Berik, Dong and Summerfield2010; Jacka, Reference Jacka2014).

Against this background, it is unclear to what extent the structural changes in China have influenced women's care-giving behaviour. The present study seeks to fill this void by examining the trends in women's engagement in eldercare in the last two decades, in line with the overarching research question, ‘How has women's care-giving for their parents and in-laws changed across their lifecourse, time periods and birth cohorts?’ By exploring the extent to which informal eldercare, one of the main forms of domestic work performed by women, has changed in post-socialist China, this study facilitates the understanding of changes in gender ideologies, which have shifted from a rejection of the separate spheres model to a re-embracement of the traditional gender roles.

Informal eldercare in China

As a major part of domestic work, traditional patterns of women's eldercare practices have been widely attributed to the cultural value of xiao (filial piety) (Zhan and Montgomery, Reference Zhan and Montgomery2003). Xiao is a Confucian concept that defines a broad range of social ethics, prescribing children's obligation to defer to parental wishes, to attend to parental needs and to provide eldercare (Whyte, Reference Whyte and Ikels2004). The Chinese character for xiao (孝) is composed of lao (old) at the top and zi (son) at the bottom, indicating children's responsibility to their parents (Li et al., Reference Li, Hodgetts, Ho and Stolte2010).

Historically, besides spouses, both adult sons and daughters played critical roles in providing care to frail elderly relatives when the multigenerational household was the predominant form. This is still the case in rural China, where formal long-term care facilities are notably absent, leaving sons and daughters-in-law to co-reside with and care for their elders (Gruijters, Reference Gruijters2017). Evidence shows that, for the collective welfare of the household, daughters are more likely to provide direct eldercare (i.e. housework and emotional support), while sons are more likely to provide direct financial support (Xu, Reference Xu2015), which is in line with the traditional gendered social division of labour, whereby women are designated as homemakers and men are breadwinners.

However, the tradition of informal eldercare is facing increasing challenges. On the one hand, China is facing increasing demand for eldercare as a result of demographic shifts. The elderly population aged 65 and over has more than doubled since reform began, from 4.29 per cent in 1978 to 9.55 per cent by 2015, while life expectancy has increased from 65.5 to 76.0 years (World Bank, 2017). On the other hand, the trend of smaller families due to the one-child policy, cultural transitions towards greater gender equality which have challenged the traditional division of domestic labour, and new work and life opportunities for women outside the family sphere due to industrialisation and urbanisation, have reduced the supply of potential informal care-givers in China. Meanwhile, shifts in gender ideology promote a ‘men outside home and women inside home’ model, suggesting that more women may take on a care-giver role. In any case, the informal eldercare provided by women in transitional China merits further investigation. In addition, the increasing age dependency ratio in China, which is the ratio of older dependents (people over 64) to the working-age population (those aged 15–64), up from 7.44 per cent in 1978 to 13.05 per cent in 2015 (World Bank, 2017), reflects this growing imbalance between the demand for and supply of family care-givers.Footnote 2 This gap needs more attention from researchers.

As a consequence, it is far from clear whether and how the structural changes in China influence changes in women's care-giving behaviour. The present study seeks to make contributions by examining how informal eldercare changes across a woman's lifecourse (age effects) and how it has changed across different periods and birth cohorts (period and cohort effects). Age effects represent ageing-related changes in individuals’ lifecourse, while temporal trends across periods and cohorts represent changes occurring in the broad social context. Period effects reflect changes that are unique to certain historical periods. Cohort effects represent the essence of social change and formative experiences (Ryder, Reference Ryder1965; Yang, Reference Yang2008).

Education and the urban–rural divide

Based on modernisation theory, some scholars have divided the history of views towards the elderly into two broad periods: the pre-industrial and the modern (Binstock et al., Reference Binstock, George, Cutler, Hendricks and Schulz2011: 59). In the former, elders were esteemed as the possessors and transmitters of tradition and respected for their knowledge, but with modernisation, technology has replaced them and elders have gradually become obsolescent, to the point that today they are viewed merely as needy individuals requiring support and care (Binstock et al., Reference Binstock, George, Cutler, Hendricks and Schulz2011: 59–61). Medical technology, scientific technology, urbanisation, literacy and education are all potential forces contributing to the declining status of the elderly (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Lai and Guo2016).

Following the logic of modernisation theory, the traditional culture of xiao is affected too (Cheung and Kwan, Reference Cheung and Kwan2009), as the suppliers of eldercare – adult children – become rational individuals through increased urbanisation and education. However, it remains unclear whether adult children's care for their ageing parents or in-laws is eroded or intensified by societal modernisation. Therefore, in addition to presenting the trends and changes in adult women's care, we must also examine how modernisation has affected adult women's provision of eldercare. Specifically, we must examine how rural–urban residency and educational level relate to adult women's eldercare for their parents or in-laws.

From the 1980s till the end of the twentieth century, not only were Chinese laws protecting women's interests enhanced, women's health, education and income also improved significantly.Footnote 3 The most significant change has been the increase in women's educational attainment. In 1986, the Compulsory Education Law was formulated. In 1999, China began to accelerate the pace of higher education growth. More importantly, in a move to promote gender equality, women's education was given priority by policy makers (Postiglione, Reference Postiglione2015: 9). As a consequence, there has been a dramatic closing of the gap in the educational levels of young men and women. From 1990 to 2000, the gap in average educational years was reduced from 1.9 in 1990 to 1.3 in 2000. This reduction is even more apparent if we consider that the rate of young girls’ school enrolment was only 15 per cent in 1949, but it stood at 98.53 per cent in 2002. Michelson and Parish (Reference Michelson, Parish, Entwisle and Henderson2000) found that in the more-developed rural areas, women enjoyed clear advantages due to the smaller gap in education level, leading them to conclude that economic development weakened the patriarchy and improved women's status in the 1990s.

The effects of education on care-giving have been found to be mixed, however. Some researchers suggest that education can fundamentally change people's views on traditional values and responsibilities (Li and Wu, Reference Li and Wu2012), while others argue that the enlightenment function of education will make the educated feel greater sympathy for the disadvantaged (Robinson and Bell, Reference Robinson and Bell1978). Several empirical studies lend support to the latter perspective. In other words, the effects of the Chinese socialist education are favourable to the xiao tradition. For instance, a recent study using national data demonstrated that, although higher education erodes patrilineal and traditional gender values, it enhances filial piety (Hu and Scott, Reference Hu and Scott2016). Another study examined whether modernisation had eroded filial piety and if this erosion was lower among citizens with higher education levels, and revealed that although the main effect of education on xiao was insignificant, education did weaken the negative contextual effects of modernisation (Cheung and Kwan, Reference Cheung and Kwan2009).

In recent decades, the Chinese urban population has more than tripled and the rate of urbanisation continues to accelerate. Following the sweeping economic reforms (first in rural areas and then in cities) and the break-up of the rationing system, residence policies also changed in the late 1980s, considerably reducing the importance of household registration and its role in regulating rural–urban migration. As a consequence, rural peasants, be they men or women, young or old, healthy or infirm, were able to receive an education, find a job, and rent a room or buy a house in cities, where the free market created a great demand for manpower (Yang, Reference Yang, Entwisle and Henderson2000).

However, as for education, the effects of urbanisation are mixed. Through simulations, one study has shown that the probability of rural elders receiving support from adult children will decrease from 0.695 in the current generation to 0.643 in the next, while the corresponding change for urban elders was from 0.611 to 0.525 (Zimmer and Kwong, Reference Zimmer and Kwong2003). Other studies have indicated that the xiao tradition has declined more notably in rural than urban areas. If this is the case, it is worth noting that rural elders are more vulnerable since they have less easy access to formal care facilities than their urban counterparts. Indeed, using hierarchical multiple regression analysis, one study that explored how the view that they are a burden affects elders’ depressive symptoms discovered that rural elders are more likely to suffer depressive symptoms than urban elders (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Lai and Guo2016). Thus, the imbalance between demand for and supply of eldercare will pose a more serious threat to the elderly in rural China.

In sum, the second objective of the present study is to examine whether and how education and the rural–urban divide affect women's care-giving behaviour. In addition, the interaction effects between age and education, and age and residency, will also be explored in order to determine whether there is change in the effects of educational level and rural–urban residency on informal eldercare across a woman's lifecourse. The next section gives details of the data, measures and methods of this study.

Data, measures and methods

Data

The current study is based on the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), an ongoing open-cohort project co-conducted by the Carolina Population Center, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and China's National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety. The goal of the CHNS is to understand how the dramatic economic, demographic and social transformations witnessed in China are affecting a wide range of health-related outcomes by collecting multi-level data from individuals, households and their communities. The open-cohort design of the CHNS allows recruitment of new participants and the departure of current participants at each wave of the survey.

Although the CHNS is not a nationally representative study, it employs a rigorous stratified multi-stage cluster design that covers nine provinces and three autonomous cities. In each province, the provincial capital, a lower-income city and four counties (stratified by income: one high, one low and two middle) were randomly selected. Villages and townships within the counties and urban and suburban neighbourhoods within the cities were selected randomly. This sampling strategy ensures substantial variation in samples in terms of geography, and economic and social development. Each CHNS participant has completed a written informed consent, and the study was approved by institutional review boards at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the National Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhai, Du and Popkin2014).

The CHNS began in 1989, but it is not possible to include that year because no measures of informal eldercare were taken. Therefore, the following eight waves, conducted in 1991, 1993, 1997, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2009 and 2011, were included in the current study. This creates a unique opportunity to separate age, period and cohort effects. Because the survey only asked ever-married, working-age (18–52) female participants to answer questions related to informal eldercare, the research described here is based on women who were married, widowed or divorced; aged 18–52; were born between 1939 and 1992; had at least one parent or in-law alive; and were interviewed in any of the eight waves (N = 14,433).

Measures

The CHNS asked the following questions of ever-married women regarding informal eldercare for their mother, father, mother-in-law and father-in-law: ‘During the past week, did you help her/him with her/his daily life and shopping?’ If the answer was ‘yes’, a second question was asked: ‘During the past week, how much time did you spend taking care of her/him?’ Informal eldercare was coded 1 if a woman said she had provided care for any of the four people identified or if the answer to the second question was above zero.Footnote 4

As noted above, the age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 52. To make the parameters more interpretable, age was centred around the grand-mean age and divided by ten. We grouped respondents into six ten-year birth cohorts, but with several exceptions. First, to ensure a sufficient number of respondents, the initial and last cohorts were broadened over a greater range of years. Second, following previous researchers’ examples, the 1951–1955 and 1956–1960 cohorts were separated because of the historical significance of the Great Leap Forward and the Three-Year Famine (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Yang and Liu2010). Cohorts were from earliest to most recent: women born in 1939–1950, 1951–1955, 1956–1960, 1961–1969, 1970–1979 and 1980–1992 were coded 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively.

Other key individual-level variables included respondents’ education and residency. Residency referred to whether a woman was interviewed in a rural or urban area. Following the example of previous research that used the same database to study informal eldercare among Chinese women (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhao, Fan and Coyte2017), education was divided into four levels: primary or below (reference group), junior high school, senior high school and above senior high school. In the present study, the number of respondents in the reference, junior high school, senior high school and above senior high school groups were 3,827, 5,815, 2,075 and 1,739, respectively.

The current study also adjusted for other factors that may be related to women's eldercare behaviour. Work status was dichotomised as currently having a job or unemployed. Another variable, work unit (state sectors versus non-state sectors), was included to denote whether the respondent worked for a government department, state service/institute or state-owned enterprise. Health status was dichotomised as poor (if the respondent had been sick or injured in the four weeks preceding the investigation) or good.

Family factors were also taken into consideration. One dichotomous variable was used to denote whether respondents had to take care of children aged six or under (coded as 1) or not (coded as 0). Co-residence with parents/in-laws denoted whether respondents lived with their mother, father, mother-in-law or father-in-law (coded as 1) or not (coded as 0). The care needs of parents or in-laws was coded as 1 if respondents reported that they needed care. The number of parents and in-laws alive was an ordinal variable ranging from 0 to 4. To facilitate the interpretation of income disparity across survey waves, women from families whose annual household income was higher than or equal to the third quartile (75%) were coded as being from high-income families (coded as 1) and others were coded as being from low- or medium-income families (coded as 0) after household income in each wave was inflated to 2011 yuan values. In addition, regional differences in economic development were categorised into five dummy variables: mega-city (Beijing, Shanghai and Chongqing, the three largest autonomous cities), coastal (Shandong and Jiangsu, the two most economically developed provinces), north-east (Liaoning and Heilongjiang), inland (Henan, Hubei and Hunan) and the mountainous south (Guangxi and Guizhou, the most economically underdeveloped regions).

Analytic methods

This study used hierarchical age–period–cohort (HAPC) logistic regression models to examine lifecourse and temporal changes in women's informal eldercare that can be attributed to the process of ageing and the social transformations that occurred in China between 1991 and 2011 (Yang, Reference Yang2008; Yang and Land, Reference Yang and Land2013). Such an analytic approach has frequently been used to address the major challenge of separating age, period and cohort effects: that linear dependency among age, period and cohort leads to an ‘identification problem’ when taking all three variables into consideration at the same time. This HAPC approach is based on the assumption that studies using fixed period and cohort effects ignore the multi-level structure of the data (Yang, Reference Yang2008). However, given that respondents who are surveyed at the same point in time and who belong to the same cohort are likely to offer similar responses, this approach recommends that researchers put the period and cohort effects at a higher level when doing the analysis. Following this rule, our model estimates the fixed effects of age and other individual-level measures and random effects of period and cohort.

The level 1 (within-cell or person-level) fixed effects can be expressed in the following form:

$$\eqalign{{\rm LogitPr}\left( {{\rm Eldercar}{\rm e}_{ijk} = 1} \right) = &{\rm \beta} _{0jk} + {\rm \beta} _{1j}AGE + {\rm \beta} _{2j}AGE^2 + {\rm \beta} _{3j}RES + {\rm \beta} _{4j}EDU \cr &+ \mathop \sum \nolimits_{\,p = 9}^P {\rm \beta} _pX_p}$$

$$\eqalign{{\rm LogitPr}\left( {{\rm Eldercar}{\rm e}_{ijk} = 1} \right) = &{\rm \beta} _{0jk} + {\rm \beta} _{1j}AGE + {\rm \beta} _{2j}AGE^2 + {\rm \beta} _{3j}RES + {\rm \beta} _{4j}EDU \cr &+ \mathop \sum \nolimits_{\,p = 9}^P {\rm \beta} _pX_p}$$where the logit of the probability of providing eldercare for an ith individual in the jth period and kth cohort is modelled as a function of age, age squared, residency, education and other correlates X. The square term of age is included to account for potential curvilinear effects of age. RES indicates where the respondent lives (urban or rural area); EDU denotes the educational attainment of the respondent (primary or below, junior, senior and above senior). X denotes the vector of other individual-level measures, including age by residency interactions, age by education interactions and control variables (work status, work unit, health status, care for children, whether living with parents/in-laws, whether parents/in-laws need care, number of parents/in-laws alive, high-income family and region). Finally, in this model, β0jk is the intercept indicating the cell mean for the reference group at mean age, interviewed in year j and born in cohort k. β denotes the level 1 coefficients and p is the maximum number of covariates.

The level 2 (between-cell) random intercept and coefficients model for estimating the period and cohort effects is expressed in the following forms:

Overall mean:

Residency effect:

Equation (2) is the model for the random intercept β0jk, which specifies that the overall mean varies from period to period and from cohort to cohort. γ 0 is the expected logit of providing informal eldercare at the zero values of all level 1 measures averaged over all periods and cohorts. μ 0j is the overall period effect averaged over all cohorts with variance τ u0. υ0k is the cohort effect averaged over all periods with variance τ υ0.

To test whether residency effects vary across periods, the equation also specifies that the coefficients of residency have period effects whose random variance components are denoted as τ u3. All the period random variance components were assumed to be distributed normally. Two standard measures, Akaike's information criterion (AIC) and Schwarz's Bayesian information criterion (BIC), were used to compare nested and non-nested models for goodness of fit. Supplementary analysis found no significant random period effects for education or random cohort effects for residency and education. Therefore, we only examined random period effects for residency. Based on the combined models of Equations (1)–(3), we next estimated the HAPC model using Stata's xtmelogit command.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the variables in the analysis. About 10.5 per cent of the sample of ever-married women aged 18–52 provided care for their parents or parents-in-law. The average age of adult women in our sample was 42.38 (standard deviation (SD) = 6.71). About 78 per cent had a job when interviewed. The co-residence rate was 37.4 per cent (SD = 0.48).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics: China Health and Nutrition Survey, 1991–2011

Notes: N = 14,433. SD: standard deviation. Ref.: reference group.

Table 2 presents fixed effects coefficient estimates in the form of odds ratios (OR) of providing informal eldercare to parents or parents-in-law and random effects variance components. We first report the overall trends in informal eldercare and then examine age variations in residency and education effects on eldercare, following which time trends of residency differentials in eldercare are explored. Results from selected models are visualised in graphs to illustrate key findings.

Table 2. Odds ratio estimates from hierarchical age–period–cohort models of informal eldercare

Notes: Ref.: reference group. AIC: Akaike's information criterion. BIC: Bayesian information criterion.

Significance levels: † p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Overall trends and differentials in eldercare

Models 1–3 in Table 2 present estimates of the level 1 individual variables: age, residence and education. Model 4 estimates the main effects of all three key variables. The results of Model 1 suggest a significant age effect net of the random effects of period and cohort. This shows that, adjusting for period and cohort variations, with every extra ten-year age increase, the odds of a woman providing care to her parents or in-laws increase by 126 per cent (OR = 2.26, 95% confidence intervals (CI) = 1.69, 3.01). However, the square term of age is indistinguishable from zero, indicating a non-quadratic age effect. In addition, net of the age effect, random effects of period and cohort in terms of residual variance components are significantly different from zero. But both period and cohort effects are smaller than the age effect. As reported in Table 2, net of the age effect, random variance components are significant at the period and cohort level. The size of variance components by period and cohort shows that cohorts explains more than periods of the overall trends in informal eldercare among Chinese women (0.45 versus 0.03).

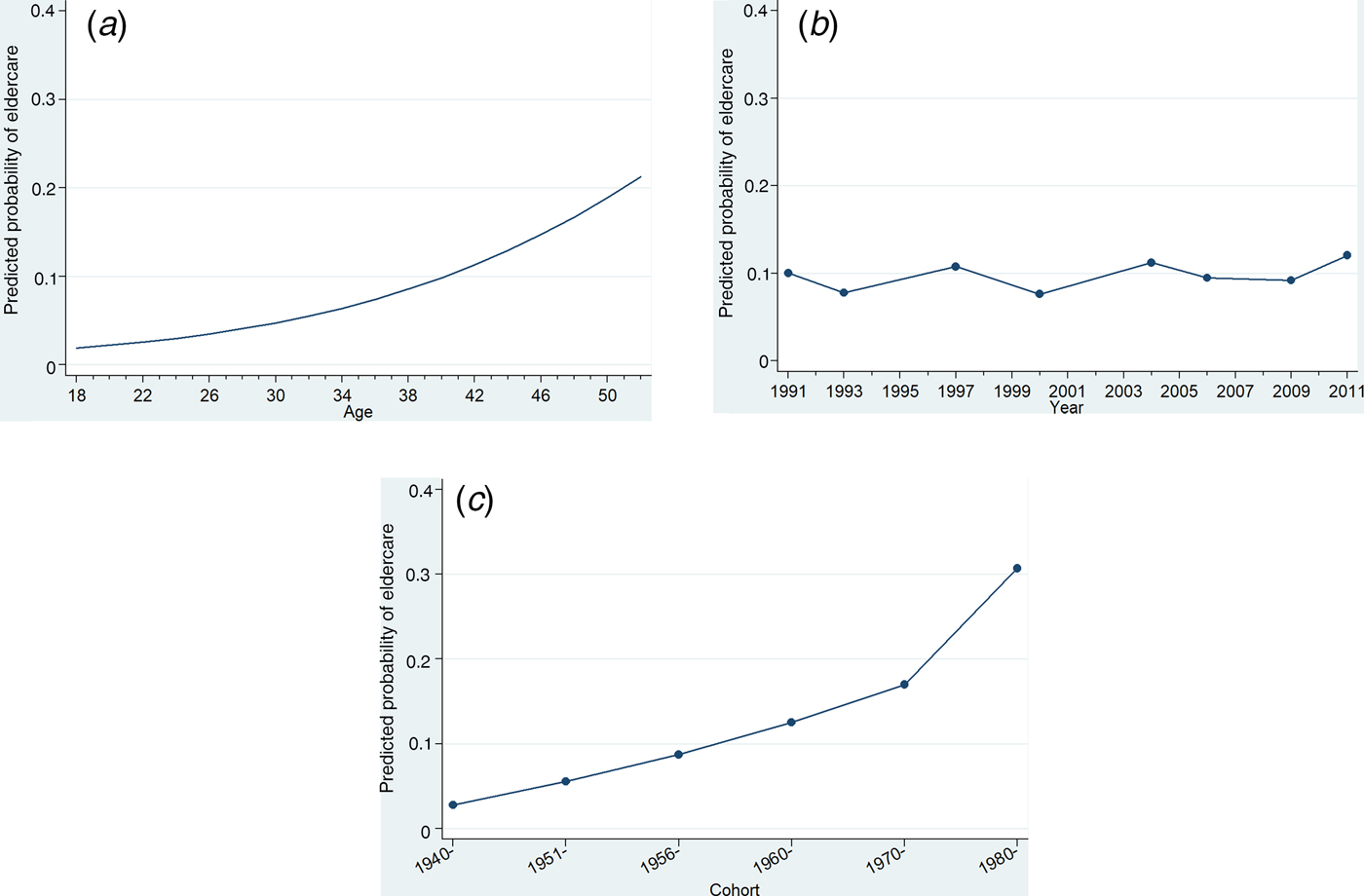

Figure 1 presents the overall age, period and cohort trends of eldercare in terms of predicted probability of providing eldercare, estimated from Model 1. Figure 1a shows the estimated age effect. The predicted log-odds are converted to probability = 1/(1 + exp(β)). The age effect also shows a linear upward tendency. That is to say, a married woman aged 18–52 is increasingly likely to take care of her parents or in-laws as she herself ages, controlling for the random effects of period and cohort. Figure 1b presents period effects estimated from Model 1 in terms of the predicted probability of women providing care to their parents or in-laws at their mean age and averaged over all cohorts, which is calculated as β0j = γ 0 + u0j, where γ 0 is the intercept and u0j is the period-specific random effect coefficient estimated from Model 1. The period effects display an overall stable trend, although there are some fluctuations. Figure 1c presents cohort effects estimated from Model 1 in terms of the predicted probability of women providing care to their parents or in-laws at their mean age and averaged over all periods, which is calculated as β0k = γ 0 + v0k, where γ 0 is the intercept and v0k is the cohort-specific random effect coefficient estimated from Model 1. Unlike the period effects, the cohort effects show an evident upward trend. It appears that the latest cohort (1980–1993) presents a significantly higher probability of providing eldercare.

Figure 1. Overall age (a), period (b) and cohort (c) effects on informal eldercare.

Models 2 and 3 estimate the effects of residency and education on informal eldercare separately. Both the residency and education effects are highly significant. In terms of residency, the estimate from Model 2 shows that women who live in urban areas are nearly twice as likely to provide eldercare to their parents or in-laws than women who live in rural areas controlling for period and cohort effects (OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.65, 2.05).

Model 3 shows a positive effect of education on informal eldercare controlling for period and cohort effects. Specifically, the odds of women who have a junior high school education providing elderly care are about 28 per cent higher than women who have completed only primary school or less (OR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.11, 1.49) and the odds for women who have a senior high school education are about 76 per cent higher than women who have completed only primary school or less (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.48, 2.11). Furthermore, women who have more than a senior high school education are twice as likely to provide eldercare than women who are less educated (OR = 2.11, 95% CI = 1.77, 2.53).

The above results still hold in Model 4 when all the variables are considered. The smaller AIC and BIC statistics indicate a better model fit for Model 4 than the former three models. Meanwhile, Model 4 suggests two other findings. One is that age, residency and education effects still exist when period and cohort effects are taken into account. The other is that significant variations in the odds of women providing informal eldercare can be attributed to period and cohort effects.

Models 5–7 are additive models to Model 4. Model 5 includes the interaction effects between age and residency and between age and education. Model 6, on the basis of Model 5, introduces a random coefficient on the binary variable, residency, to allow for separate random effects within each period for urban and rural areas. Model 7 introduces other control variables that may be related to women's informal care-giving behaviour. The very low AIC and BIC statistics suggest that Model 7 has a better fit than all previous models.

Age variations in residency and education effects on eldercare

To explore whether there are changes in the effects of education and residency on eldercare provision when people age, Model 5 includes the interaction effect between age and residency and between age and education. The results of Model 5 show that the interaction effect between age and residency is significant, while that between age and education is insignificant. This means that, adjusting for other factors, the difference between urban women and rural women in eldercare provision decreases with women's age.

Such a result is further corroborated by Model 6 when the random period variations in residency slope are taken into account. Inclusion of the random slope for residence hardly affects the interaction effect. This once again indicates that residency differentials in informal eldercare provided by adult women vary significantly with age. However, education gaps in eldercare do not significantly vary with age.

Model 7 differs from previous models in that the effects of other correlates are included.Footnote 5 As expected, most control variables are related to women's provision of informal eldercare. In our sample, 78 per cent of women had a job when they were interviewed. Although working status does not show a significant relationship with women's informal eldercare behaviour, the type of work unit matters marginally. Relative to women who work in non-state sectors, women who work in government departments, state service/institutes or state-owned enterprises are slightly more likely to provide care to their parents or in-laws (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 0.97, 1.44). With regard to care-giver health status, it is surprising to find that women who had been sick or injured in the previous four weeks were more likely to care for their parents or in-laws (OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.03, 1.41). One possible reason is that if women are at home because they are convalescing, these women are more available to care for elders, who are also at home. In addition, comparing women with and without a child aged six or younger at home, adjusting for other factors, women who care for young children are associated with a 16 per cent reduction in the odds of providing eldercare (OR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.69, 1.01). Living with parents or in-laws increases the odds of providing eldercare by about 50 per cent (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.27, 1.76).

In addition, it appears that the care needs of parents/in-laws have an extremely strong effect on women's informal eldercare behaviour. The odds of providing care are ten times higher among women whose parents or in-laws need care than women whose parents or in-laws do not (OR = 10.55, 95% CI = 9.07, 12.26). The relationship between family income and family informal eldercare is insignificant. It is possible that although they provide less direct care, women from high-income families provide more indirect care such as financial support or purchased formal care. The number of living parents or in-laws is negatively related to the provision of care. Each additional living parent is associated with a 25 per cent reduction in women's ability to provide informal eldercare (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.57, 0.98). In terms of region, the estimates show that, relative to women from the mountainous south, those from autonomous cities, coastal regions and the north-east are about 105, 90 and 68 per cent more likely to care for their parents or in-laws, respectively.

Time trends of residency differentials in eldercare

Compared with Models 1–5, the SD of the random intercept for period and cohort in Model 7 decreases after controlling for other covariates (not reported). Controlling for these covariates removes some of the unexplained variability at the period level that was previously explained by larger variance of the random intercepts for period. Therefore, in the last model there is less variance of the random intercepts for period and cohort.

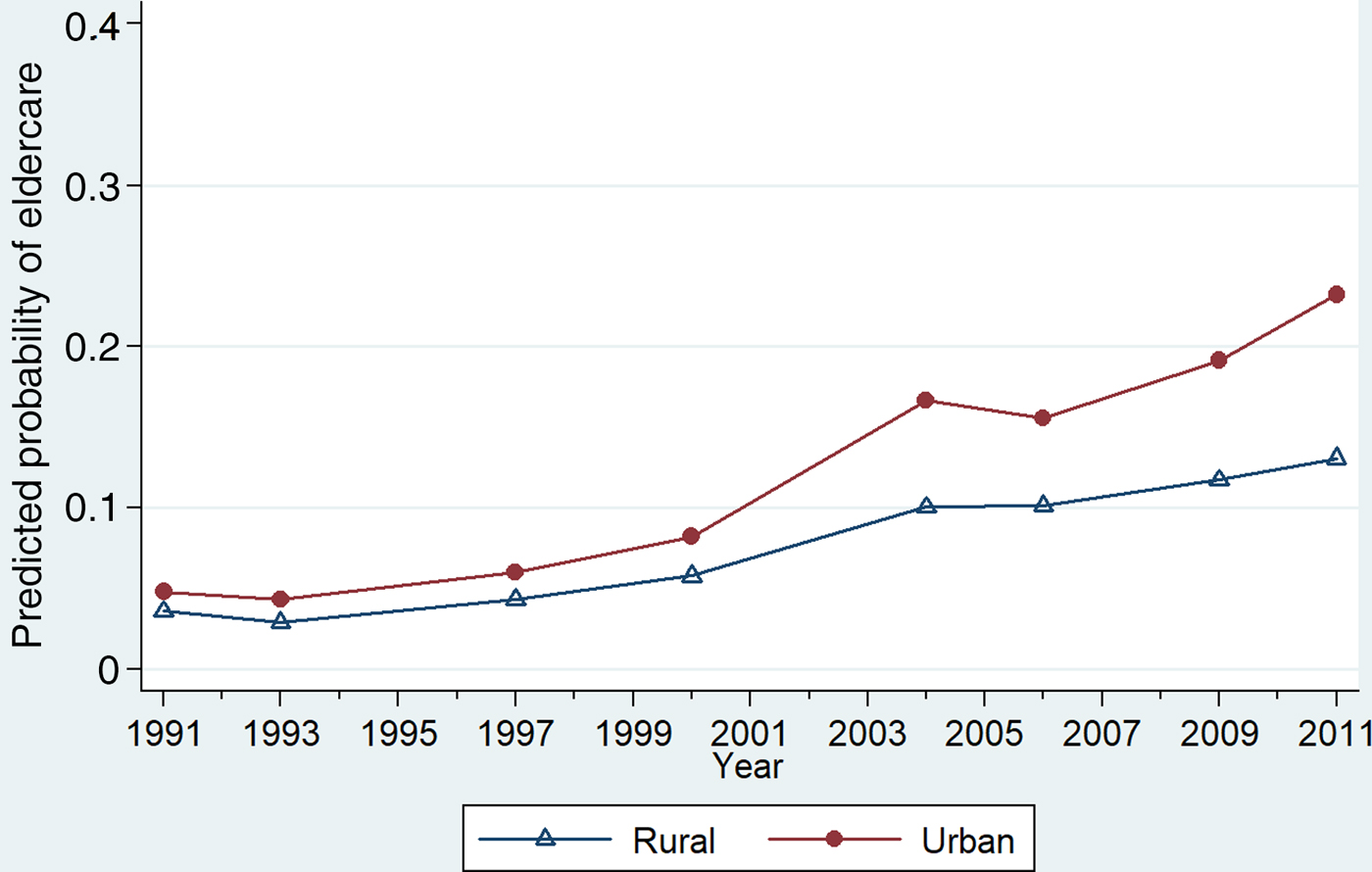

Residency differentials are not statistically significant in Model 6, but when adjusted for other factors, these differentials become significant in Model 7 (p < 0.05). Figure 2 visualises the estimated results from Model 7. The predicted probabilities are calculated from the estimates presented in Model 7 (the fully adjusted model) of Table 2. It shows that residency disparities in eldercare behaviour have increased during the last 20 years in China. The residency differentials are small in the first decade, but the gap increases sharply, especially after 2000. Although there is a small decline from 2004 to 2006, by 2011 the gap reaches a historical peak and shows no signs of decline. However, for both urban and rural women, there is an upward trend in providing informal care, although it is faster among the former.

Figure 2. Predicted period variations in residency disparities.

Discussion and conclusion

From the Maoist to the post-socialist era, China seems to present a reversed gender-revolution. Post-socialist Chinese seem to have turned once again to the separate-spheres ideology of men working outside the household and women inside the household. As China is both a post-socialist country that is still influenced by the socialist discourse of gender equality and a ‘third world country’ that is facing strong demands in modernising its economy, the provision of informal eldercare in transitional China merits further investigation. Thus far, however, it is unclear to what extent the traditional filial pattern of eldercare still holds in the post-socialist China.

The current study places analysis of informal eldercare in the context of China's transition from state socialism to a dual-structure economy. Specifically, using eight waves of CHNS data for the period 1991–2011, this study has investigated the lifecourse and temporal changes in ever-married women's engagement in informal eldercare as well as variations across different sub-groups in China. A HAPC model used to disentangle the confounding effects of age, time period and birth cohort revealed five key findings.

First, with an increase in age, the probability of a woman providing informal eldercare increases, which supports previous findings (Zuo et al., Reference Zuo, Wu and Li2011). The average age of female care-givers was 42.38 (SD = 6.71), which is close to the average age of 46 found among female informal care-givers in another study, conducted in the United States of America (Navaie-Waliser, Spriggs and Feldman, Reference Navaie-Waliser, Spriggs and Feldman2002). The results show that among 18–52-year-old women, there is a strong upward trend of providing informal eldercare to parents or in-laws. Every ten-year increase in age raises the odds of providing care to parents/in-laws by 126 per cent. Although the maximum age in the CHNS data is 52, we can expect women to continue to provide informal care to their parents or in-laws beyond that age. As revealed by a previous study, when people retire, ‘young’ elderly still care for ‘old’ elderly (Liu, Reference Liu2016). Therefore, the prevalence of women's care-giving behaviour is expected to continue.

Second, the provision of informal eldercare changes over time. The period effects display a relatively stable trend, with some variations. Observed rates show that since 2000, women have become increasingly likely to provide care to their parents or in-laws, which illustrates the rising prevalence of informal eldercare in China. One possible explanation involves the relationship between the formal eldercare provided by the government and informal eldercare provided by family members. Although no final conclusions have yet been reached on this issue, the number of recipients of Minimum Living Security, one of foremost formal elderly welfare systems in China, has steadily increased since the turn of the millennium, from 0.7 million in 2000 to 7.58 million in 2011 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2000–2011), suggesting concomitant increments in both formal and informal eldercare. Indeed, early studies revealed that old people's three main sources of income had changed from children and relatives, labour income and pensions in 1994 to children and relatives, pensions and labour income in 2004 (Du and Wu, Reference Du and Wu2006). Du and Wu (Reference Du and Wu2006) have further indicated family members’ central role in eldercare despite the increasing significance of formal institutional support.

Another possible explanation lies in the increasing demand for eldercare, as suggested by the Fifth and Sixth National Population Censuses: the number of households with at least one individual aged 65 or over has increased rapidly, from 68.39 million in 2000 to 88.04 million in 2010 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2000, 2010). When formal eldercare is insufficient, changes in population structure lead more women to take care of elderly family members. The persistence of the tradition of xiao is another possible contributor. Previous studies suggest that even though China has undergone drastic social changes, the culture of xiao is not declining (Zhan, Reference Zhan2004), and other traditions, such as patrilineal and gender values, remain prevalent and resilient (Hu and Scott, Reference Hu and Scott2016). Finally, changes in public holidays after 1999 may be another possible factor. From 1999 onwards, with the gradual growth in popularity of the ‘golden week’, statutory public holidays have increased, from seven days in 1949, when China was established, to 11 days in 1999, when labour and national holidays were extended (State Council, 1999). The longer holiday allowances provide more opportunities for adults to visit their elderly parents or in-laws.

Third, the cohort differentials in women's informal eldercare are significant. It appears that even after China experienced a period of rapid change in women's participation in the labour market and attitudes towards work and family life, women from more recent birth cohorts are increasingly likely to provide care to their parents or in-laws. Women are still the main force in providing care for ageing family members and the rates of care provision become particularly striking among the last four cohorts (the mid-1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s). This finding further confirms the ideology of the ‘good daughter-in-law’ and ‘good daughter’ in China, suggesting that although there are no longer barriers to women's engagement in paid work, they are still expected to be primary care-givers. Similar findings have been obtained in other studies. For instance, using a national survey, Hu and Scott (Reference Hu and Scott2016) discovered that more recent cohorts do not appreciate the tradition of xiao any less than their predecessors. In fact, they found that, contrary to general expectations, more recent cohorts hold more traditional attitudes regarding xiao. One possible reason is that recent cohorts are being greatly influenced by the one-child policy and have fewer siblings to share the care-giving burdens, leaving them a higher chance to be involved in eldercare.

The above findings are related to a more comprehensive debate about the gender-based divisions of labour in China. That is, debate over whether household divisions of labour have changed dramatically with China's economic transition. On the one hand, some researchers have argued that, along with economic improvement and the one-child policy, increased work opportunities in the market have enabled women to reject their traditional family role for new and even reputable positions in broader society and thus achieve the goals of women's liberation (Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, Wu, Hwang and Scherer2007; Tsui and Rich, Reference Tsui and Rich2002). On the other hand, some researchers consider the division of domestic labour to be an unchanging fact (Zuo and Bian, Reference Zuo and Bian2001; Zuo, Reference Zuo2003; Chen, Reference Chen2005), arguing that Confucian familial philosophy, which underlines women's roles in filial care, service to parents, the moral instruction of children and personal normative practices, is far from marginalised or discarded. Thus, as recent studies have shown, the resurfacing of women's domestic roles in political discourses in the post-socialist era partially led to women's withdrawal from the employment market and their return to traditional wifely and motherly roles (Wu, Wang and Huang, Reference Wu, Wang and Huang2015). The results of the present study provide evidence supporting the latter proposition.

Further, there are age variations in the residency differentials of informal eldercare behaviour. Women who live in urban areas are nearly twice as likely to provide eldercare to their parents or in-laws than women who live in rural areas, controlling for period and cohort effects. However, this gap decreases as age increases, indicating increasingly heavy responsibilities for both rural and urban women. The rural elderly face a more serious challenge in changes to the traditional pattern of eldercare (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Lai and Guo2016). Consequently, some scholars have called for more attention to address the urgent needs in rural areas (Zhang and Goza, Reference Zhang and Goza2006). Education is one means to address the challenges faced by the relatively disadvantaged rural elderly. Some empirical studies suggest that formal school education can act as a means of sustaining filial piety in the face of modernisation (Cheung and Kwan, Reference Cheung and Kwan2009).

Last, but not least, although no age variations in the education differentials of the supply of informal eldercare have been found here, the results indicate that women with higher educational attainment are more likely to provide care to their parents or in-laws. A woman who has received 13 years of education or more is twice as likely to provide eldercare than a woman who has received six years or less. This is consistent with previous findings that the Chinese socialist education cultivates filial piety and that informal eldercare continues despite modernisation (Cheung and Kwan, Reference Cheung and Kwan2009; Hu and Scott, Reference Hu and Scott2016). This result also confirms previous findings that married women who have completed more education tend to make greater efforts to provide both eldercare and childcare when allocating intergenerational family resources (Di and Zheng, Reference Di and Zheng2016).

The present study has two significant limitations. First, due to the survey design, 97 per cent of the women in our sample were married. However, there is evidence that more and more women are delaying marriage, choosing co-habitation with their boyfriend but not marriage, or remaining part of the never-married group. How often and how long these women provide care may differ. It is possible that women who choose to remain single may provide more care to their ageing parents. Meanwhile, as mentioned earlier, the maximum age in the sample is 52, which represents another limitation, as previous studies have shown that women beyond 52 remain the main force in caring for elderly relatives. Additionally, the CHNS considers only adult women for parents’ care, which is insufficient to explain the traditional pattern of informal care since some studies have revealed that elderly people are mostly cared for by their spouse, even if they co-reside with adult children (Gruijters, Reference Gruijters2017).

Second, the CHNS asked about women's informal eldercare behaviour, but not about men's. Further interesting findings related to gender disparities and trends in the supply of informal eldercare could be obtained by comparing and contrasting the care-giving experiences of male and female carers if we had data on men's care behaviour. Previous studies have found gendered divisions of labour in eldercare behaviour (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Ma and Shi2009; Xu, Reference Xu2015). For instance, women, who usually receive lower pay in paid market work tend to do more unpaid work in the domestic sector (such as housework), while men, in contrast, who usually receive higher pay, tend to provide direct financial help to parents (Xu, Reference Xu2015). However, we do not yet have relevant data to explore these differences in informal eldercare between men and women and its trends across age, period and cohort.

Acknowledgements

This research uses data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS). We thank the National Institute for Nutrition and Health, China Center for Disease Control and Prevention. This work was supported by the National Institute for Health (NIH); the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (R01 HD30880, P2C HD050924); the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (R01 DK104371); the NIH Fogarty (D43 TW009077; for the CHNS data collection and analysis files since 1989); the China–Japan Friendship Hospital; the Ministry of Health (for CHNS 2009), the Chinese National Human Genome Center at Shanghai (since 2009); and the Beijing Municipal Center for Disease Prevention and Control (since 2011).