The story of Isaac and his sons, Esau and Jacob, was fraught with meaning for both the Christians and the Jews in the Middle Ages. Esau and Jacob were twins who struggled already in their mother Rebecca’s womb. Esau was born first, hairy and red, while Jacob came right after, holding onto Esau’s heel. Genesis 27 tells the story of Isaac, going blind in his old age, who summons Esau, his favorite, and sends him off to hunt: “Thou seest that I am old, and know not the day of my death. / Take thy arms, thy quiver, and bow, and go abroad: and when thou hast taken some thing by hunting, / Make me savoury meat thereof, as thou knowest I like, and bring it, that I may eat: and my soul may bless thee before I die” (Genesis 27:1–4). The conversation is overheard by Rebecca, who hastens to warn her own favorite, Jacob, and they hatch a plan. Rebecca helps Jacob dress into Esau’s smelly hunter’s garments, wraps his hands in lamb skin, cooks up Isaac’s favorite meal, and sends Jacob to see Isaac in his brother’s stead. So deceived, the unseeing Isaac blesses Jacob instead of Esau, discovering the deception only when Esau returns from the hunt. But it is too late. Distraught at his brother’s deception, Esau exclaims: “Hast thou only one blessing, father? I beseech thee bless me also.” And Isaac, who has just appointed Jacob Esau’s lord, pronounces the fateful words: “In the fat of the earth, and in the dew of heaven from above / Shall thy blessing be. Thou shalt live by the sword and shalt serve thy brother: and the time shall come, when thou shalt shake off and loose his yoke from thy neck” (Genesis 27:38–40). Jacob, fleeing Esau, goes into exile but returns triumphant, the father of the twelve tribes.

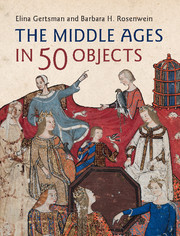

This historiated T initial presents a pivotal moment in the story. Isaac, who towers over his son, lies in an enormous bed. His eyes are closed, to indicate his blindness, and he turns away from Esau, his right hand resting on top of the red coverlet, his left ostensibly touching Esau to ascertain his identity. Isaac’s head is framed by a halo; his hair is well-coifed, his beard neatly parted and curling at the ends, his skin white and unblemished. Esau, by contrast, is hairy and scruffy, his hands, face, and neck covered in stubble. He kneels before the bed, his bow in a sling at his back. The blue of Esau’s cloak stands out against the red coverlet, itself set in contrast with the green wall behind Isaac. The stem of the letter T, painted with white floral motifs, serves to accentuate Esau, as does the blue flourish below his feet.

The narrative was understood as a tense religious struggle by both Christians and Jews, although the two groups interpreted it quite differently. For Christians, the triumph of the young Jacob over his older brother was the victory of the New Testament over the Hebrew Scriptures. Jews, conversely, conceived of Esau as the embodiment first of Edom, then of Rome, then of Christians as a whole, while Jacob symbolized Israel and Judea. The episode spoke particularly strongly to the late medieval European Jewry, banished from England in 1290, from France in 1306, from Spain in 1492, and from many cities everywhere else in Europe. For Jews, Jacob signified redemption, the ultimate triumph of the chosen people. To such a beholder, any image of Esau and Jacob—and these images appeared frequently in the illuminated Haggadot, the ritual books for the Passover—was pregnant with messianic meaning, with the promise of deliverance.

But the book that included the image pictured here was neither made nor used by a Jewish community. A large illuminated initial, here incised from a choral manuscript, it was doubtless painted by one of the many professional Christian artists working in northern Italy at this time. Books such as these were quite enormous in order to allow all the members of a choir to see the words and music. The large T in this miniature marked the beginning of the first word, “Tolle,” in a chanted response for the matins of the second Sunday in Lent: “Tolle arma tua,” or “Take up your weapons.” All antiphonaries contained these words and music for that day, and some featured illustrations, like this one, of the moment when Isaac calls on his firstborn to take his weapons and go out to hunt. Just as the liturgy was made up primarily of psalms that were understood as prefigurations of the Christian message, so too was this passage from Genesis.

Although neither the artist nor the users of this book would have cared much about the Jewish significance of Isaac and Esau, the artist was obliged to imagine how to reconstruct the scene. That may not have been as difficult as it sounds. Although the fifteenth century saw a proliferation of laws to keep Christians and Jews apart, many Jews lived in (or, rather, on the outskirts of) northern Italian cities, where they were appreciated for their economic contributions and were allowed to observe their religious practices, build synagogues, construct cemeteries, and celebrate their holidays. Christians consulted Jewish doctors and borrowed from Jewish money-lenders (along with pawn-brokering, money-lending was one of the very few professions that Christian communities left open to Jews). The creator of this initial, in other words, may have known something about local Jewry and their death rituals.

Some of these were described in an account by Elijah Capsali (d.1555), who studied in Padua with Rabbi Judah Mintz. When the rabbi lay dying in 1509, writes Capsali, he summoned “all the rabbis of Padua, among them my teacher Rabbi Isserlein, and these brave men of Israel gathered around his bed […] Then in their presence he conferred rabbinical ordination upon Rabbi Isserlein and ordered them to do him honor. He laid his hand upon him, blessed him and commanded him saying: ‘Now I am dying. May the Lord be with you’ […] Rabbi Abba Shaul [del Medigo] and I also were there to receive his blessing. After which, his son Rabbi Abraham Mintz approached, with his own children. The dying man had them come next to him on the bed, placed his hands upon their heads, kissed them and embraced them. When he had finished blessing his descendants, he composed his feet upon the bed and died.”

The death of Rabbi Mintz (on Friday) was followed by burial (on Sunday). The whole community of the synagogue fasted, suspended work, constructed a coffin, and began the burial rites at the home of the dead man. There “the rabbis and notables stepped to the fore, raised up the deceased, and carried him on their shoulders to the room in the courtyard, whose walls had been draped in black.” After stacking up holy books next to the bier, the men (including young Capsali) lit torches and listened to a long homily. Then they processed to the cemetery, during which all the men “considered worthy” took turns carrying the coffin. Once at the grave site, “Rabbi Hirtzen then came forward, recited the prayer, and raised up a great lamentation.” At last, the body was transferred to the grave, its head placed on a special copy of the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. Rabbi Mintz was a great man in the eyes of his community, a righteous man in the mold of Abraham and Isaac; were Isaac to have lived and died in late medieval Italy, he would undoubtedly have merited an equally elaborate ritual.