INTRODUCTION

Market interactions occur within a framework of legislative and policy constraints and bureaucratic rules; within this framework, firms actively pursue political strategies (Henisz & Zelner, Reference Henisz and Zelner2005; Hillman, Keim, & Schuler, Reference Hillman, Keim and Schuler2004), which are defined as coordinated firm actions that target a country's political system and seek to influence political decisions and policies to advance a firm's private ends (Hillman, Zardkoohi, & Bierman, Reference Hillman, Zardkoohi and Bierman1999). The rapidly growing literature in this field has examined how firms engage in political activities and how they develop political capabilities (Henisz & Delios, Reference Henisz, Delios, Ingram and Silverman2002; Henisz & Zelner, Reference Henisz and Zelner2005; Hillman & Hitt, Reference Hillman and Hitt1999; Holburn & Zelner, Reference Holburn and Zelner2010; Li, Meng, & Zhang, Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006). This article adds to this stream of research by examining the relationships between firms' characteristics and their political strategies. I investigate whether firms' market capabilities (i.e., those attributes that enhance a firm's ability to succeed in competitive markets – such as production efficiency, consistently superior R&D, or brand awareness) substitute for or complement firms' political actions, and whether the institutional context moderates this relationship.

Prior research on corporate strategies in the political arena has drawn different conclusions about the nature of political activities. On the one hand, a substantive body of research has focused on how firms engage in political activities to seek refuge from competitive forces, such as by lobbying for trade protection, pursuing preferential treatment, and seeking government bailouts (e.g., Faccio, Masulis, & McConnell, Reference Faccio, Masulis and McConnell2006; Grier, Munger, & Roberts, Reference Grier, Munger and Roberts1994; Hillman, et al. Reference Hillman, Keim and Schuler2004; Lenway, Morck, & Yeung, Reference Lenway, Morck and Yeung1996). This prior research suggests that such political strategies are most attractive to those firms that are ill-equipped to compete in the market without the aid of government intervention because the benefits gained by pursuing political strategies compensate them for their weak market competitiveness (Lenway et al., Reference Lenway, Morck and Yeung1996; Morck et al., Reference Morck, Sepanski and Yeung2001). For instance, in the U steel industry, research has shown that firms that engage in active lobbying tend to be industry laggards with lower levels of innovation and profitability than non-lobbying firms (Lenway et al., Reference Lenway, Morck and Yeung1996; Morck et al., Reference Morck, Sepanski and Yeung2001). More generally, those industry participants facing threats to their survival from international competition frequently turn to the government for trade protection (see, for example, Cashore [Reference Cashore1997] on softwood producers and Baron [Reference Baron1995] on the cement industry). Such political activities frequently generate economic returns for these firms by redistributing wealth – i.e., by benefiting certain firms at the expense of other stakeholders (because consumers and competitors are disadvantaged by trade protection) – and are thus labeled ‘directly unproductive profit-seeking (DUP)’ by public choice theorists (e.g., Bhagwati, Reference Bhagwati1982, Reference Bhagwati1983).

On the other hand, political strategies do not result in DUP activities under all circumstances. Some studies argue that firms in developed markets use political strategies to access information and improve their legitimacy, which actually creates value (e.g., Hillman et al., Reference Hillman and Hitt1999). Similarly, in countries in which the quality of the market-supporting institutional environment is circumscribed by inadequately protected property rights and weak legal systems (as is true in many emerging economies), it is frequently observed that firms have strong incentives to employ political strategies to protect their earnings from state expropriation – i.e., from politicians and bureaucrats infringing on firm property – which helps safeguard firm value (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006; Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007). Safeguarding property constitutes a more ‘productive’Footnote [1] or ‘value-creating’ role for political strategies because, in this manner, such strategies are engaged in order to protect firm value from state expropriation, which actually incentivizes firms to produce more value in the market and results in greater overall benefit. This approach is thus sharply different from the DUP purpose: firms benefit from the additional value created rather than from redistributions of wealth at the expense of other stakeholders.

The risks of state expropriation are particularly salient when the government is above the law and uses its power to extract rents from firms, which is dubbed ‘the grabbing hand’ in theories of political economy (e.g., Frye & Shleifer, Reference Frye and Shleifer1997). Although prior research on firms' political strategies in the context of emerging economies has investigated how political risks affect firms' market activities and how prior experience helps firms implement political strategies to address such risks (e.g., Henisz & Zelner, Reference Henisz and Zelner2005; Holburn & Zelner, Reference Holburn and Zelner2010), little is known about the relationship between firms' market competitiveness and the political strategies that firms employ to alleviate state expropriation in these contexts.

This study aims to address this gap in the research. I argue that there are reasons to believe that firms' market capabilities can be positively related to their political strategies rather than being negatively associated with such strategies (as is postulated by research of the DUP-type political strategies). I also argue that firms with greater market capabilities reap higher benefits from engaging in political strategies aimed at reducing the hazards of expropriation because such firms have higher-value assets at risk of expropriation and would thus benefit disproportionately from protecting such assets. Building on this baseline assumption, I utilize the inter-provincial variation in multiple aspects of the market-supporting institutional environments in China to investigate how the relationship of interest varies in different Chinese provinces. I tested the hypotheses with a sample of privately owned enterprises (POEs) in China. The results show that firms' market capabilities – as indicated by their asset turnover ratios and R&D intensity – are positively related to their political participation and that this relationship is weaker in provinces that have more effective constraints on governmental power, more supportive policies for private sector growth, and more developed legal systems.

This study intends to make the following theoretical contributions. First, it highlights an important but largely neglected scope condition in theories of corporate political strategy: political strategies can vary dramatically in terms of the specific mechanisms through which they generate economic benefit for firms, while determining which firms are more likely to pursue political strategies depends strongly on this difference. The body of previous studies that has described firms' political activities as DUP strategies that are rent-seeking in nature (and have thus found weak firms to be more politically active in pursuing insulation from market competition, e.g., Baron, Reference Baron1995; Lenway et al., Reference Lenway, Morck and Yeung1996; Morck et al., Reference Morck, Sepanski and Yeung2001) typically assumed contexts in which strong market-supporting institutions are in place and expropriation hazards are largely non-existent. This study extends the theoretical scope of corporate political activities by focusing attention on the ‘productive’ or ‘value-creating’ roles for political strategy – specifically, firms might aim their political activities at gaining protection against the hazards of expropriation, thereby enabling them to achieve efficiency gains that might be unattainable when there are high expropriation hazards. In this case, stronger firms are found to be more active in pursuing hazard-reducing political strategies because they have generated greater value in the market that may be at risk of expropriation.Footnote [2]

Second, by investigating the circumstances affecting how a firm's market competitiveness relate to its political strategies, this study contributes to the emerging literature on ‘integrated strategies’ (e.g., Baron, Reference Baron1995, Reference Baron1997). Despite the powerful ideas behind integrated strategies, research on why and how firms coordinate their nonmarket and market strategies remains in its infancy. For example, distinguishing the different mechanisms through which political strategies might yield economic returns (and thereby relate directly to firms' market activities) has received little attention. This study addresses this research gap by explicitly examining how firm characteristics (and the market capabilities of those firms, in particular) affect the way in which they pursue political strategies.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The next section introduces the institutional context. I then develop hypotheses, establish the empirical analysis, discuss the results, and finally conclude with the theoretical and managerial implications of this study.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Institutional Background: The Chinese Private Sector

The Chinese private sector provides an excellent empirical context for studying firms' political strategies because it is a prominent example of an institutional environment that exhibits public expropriation hazards due to underdeveloped market-supporting institutions. China is recognized as a country with limited property rights protection in which the development of contract law and its enforcement has lagged far behind its economic growth (Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, & Shleifer, Reference Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2003). Prior to 1978, China suppressed privately held assets and excluded private entrepreneurs from legitimate economic exchange; the term ‘private’ was itself taboo, and there was no protection of private property rights. However, the state's position regarding privately owned firms evolved gradually from strict prohibition to tolerance, accommodation, and encouragement (Peng, Reference Peng2004). Coexisting with weak protection of private property is the absence of constraints on government power, both in policymaking and implementation and within the legal and judicial systems (Potter, Reference Potter1999). Insubstantial constraints on governmental power offer the governments and bureaucrats many opportunities to expropriate private property, including collecting bribes and seizing assets (Nee & Cao, Reference Nee and Cao2011; North & Weingast, Reference North and Weingast1989; Zhang, Chen, Chen, & Ang, Reference Zhang, Chen, Chen and Ang2014).

Moreover, provinces in China vary significantly in their economic and institutional development (Heston & Secular, Reference Heston, Sicular, Brandt and Rawski2007); the checks and balances on governments' power are significantly stronger in some locations than in others (Cull & Xu, Reference Cull and Xu2005). The genesis of regional disparities can be traced to several causes. As the central government adopted the ‘decentralized experimentation’ approach and conducted trial reforms in a limited number of localities in China's economic reforms, legal and regulatory arrangements have favored certain regions (particularly the coastal regions) over others, and the provinces have the authority to develop their own variations of new institutions (Li, Reference Li2003).

The set of political strategies available to Chinese private entrepreneurs is more limited than in most developed economies. Chinese law prohibits campaign contributions (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006; Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006), and lobbying was not a viable alternative prior to recent legislative changes (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2005). Thus, one of the most important political strategies available to Chinese private entrepreneurs is to participate directly in one of the two key policy-making institutions, the People's Congress (the Congress) or the People's Consultative Conference (the Conference) as deputies (e.g., Jia, Reference Jia2014; Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2014). The Congress plays a particularly important role in the political system because it drafts and approves laws and policies, oversees their enforcement, and monitors administrative bureaus (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006; Potter, Reference Potter1999; Shi, Reference Shi1999). Once characterized as mere ‘rubber stamp’ operations, even local Congresses have become increasingly assertive in their relationship with other political institutions since the reforms of the mid-1990s (Manion, Reference Manion2008). The Conference plays a more consultative role in policy-making by providing opinions to shape the decisions of the Congress. The Conference also monitors and advises every level of government through regular meetings with the Chinese Communist Party and other government officials (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006; Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006). The Congress is required to respond to advice from the Conference, typically within a limited amount of time (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006). Serving as a deputy in either the Congress or the Conference thus significantly increases a private entrepreneur's political connections with government officials and allows him/her to be directly involved in political decision making (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006).Footnote [3] Finally, informal political connections with politicians and bureaucrats (often referred to as guanxi with government ties) are also important in China, as in many other emerging economies (e.g., Chen, Chen, & Huang, Reference Chen, Chen and Huang2013; Fisman, Reference Fisman2001; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2005; Li, Yao, Sue-Chan, & Xi, Reference Li, Yao, Sue-Chan and Xi2011; Siegel, Reference Siegel2007). Unfortunately, good measures of informal political networks are difficult to construct and are not available from the survey data used here. Direct political participation nonetheless enhances firms' opportunities to build influential informal ties.

Chinese private entrepreneurs have always been enthusiastic about participating in politics (e.g., He & Tian, Reference He and Tian2008; Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2014). Successful efforts by entrepreneurs to gain deputyships have also received increasing attention from the public in recent years. Indeed, this phenomenon has become somewhat controversial because private firm owners are overrepresented in the Congress and the Conference relative to citizens from other walks of life, particularly peasants and factory workers.Footnote [4] There is some concern that private firm owners might use their positions to pursue private interests rather than those of their constituents, even though recent research also suggest that the political pursuit of successful entrepreneurs could be fueled by a pro-social or pro-public motive (Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2014).

Entrepreneurs seeking to become deputies in their local Congress must be elected. Serving as a deputy does not require a full-time commitment and terms range from three to five years. Local citizens elect Deputies to the Congress in their administrative area, although local and central governments – and the Chinese Communist Party – also have significant influence on the outcomes of elections (Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006; Shi, Reference Shi1999). By contrast, conference deputies are selected by a standing committee, based on nominations from various social and economic organizations. In either case, an entrepreneur seeking to become a deputy must invest considerable resources in the process because successful election or appointment to the Congress or the Conference relies heavily on efforts to build good relationships with the government, social groups, and the citizens of a precinct. In particular, governments play an important role in selecting deputies in the organizations; therefore, the considerable amount of resources and time that private entrepreneurs devote to obtain a deputyship are typically geared toward building relationships with governments and obtaining government endorsement. Firms' proactive efforts aimed at building good relationships with governments and local citizens play a crucial role in boosting their chances of obtaining deputyships in these political organizations. Indeed, the government and the Chinese Communist Party both play significant roles in the selection process (Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006), although the Conference is considered to be more independent from the Party and the government than the Congress (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006). I address government selection issues in the theory and the robustness checks sections below.

Baseline Relationship: Market Capabilities and Political Strategies

Investing in political strategies and political capabilities that allow firms to actively engage with government can help firms reduce public expropriation hazards in many ways. First, political strategies can provide superior access to timely and accurate information from the government. Such information helps a firm stay abreast of changes in laws and policies and to anticipate changes in the policy environment (Schuler, Rehbein, & Cramer, Reference Schuler, Rehbein and Cramer2002), which is particularly salient in emerging economies in which policies and regulations change constantly and the general communication of these changes to the public is inadequate (Luo, Reference Luo2003). Second, political strategies may enable firms to more effectively seek justice against public expropriation through their influence on government and/or political actors (Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). Indeed, anticipating such political influence may ex ante reduce the incidence of expropriation experienced by politically connected firms (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006), which is highly relevant when the government has broad discretion over how laws and policies are interpreted, implemented and enforced (Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007).

Political strategies also enable firms to obtain greater political and legal support to alleviate the hazards of expropriation by other private parties by enforcing their contractual relationships with transaction partners more effectively, including preventing contracting partners from reneging on contractual agreements. Political strategies may help firms be more effective in seeking justice in response to private expropriation by leveraging their influence on the government and/or the political system because the institutional environment in many emerging economies encourages politically powerful entities (whether firms or government officials) to influence law enforcement in the judicial system (Malesky & Taussig, Reference Malesky and Taussig2008). In many countries with less developed market-supporting legal institutions, courts are not politically independent and have become tools of governance (Clarke, Murrell, & Whiting, Reference Clarke, Murrell, Whiting, Brandt and Rawski2008) such that firms have the opportunity to use political strategies to influence court rulings to their advantage. For instance, Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann (Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2003) found that firms in some Eastern European transition economies that have better access to public officials are able to better ensure fair treatment against transgressions. In China, private entrepreneurs with stronger political connections may gain special attention and priority treatment by the courts, and the legal protection against private expropriation in these ‘special’ cases is more active and effective than in average cases (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006). Indeed, anticipating these outcomes may reduce ex ante the incidence of private expropriation experienced by firms with greater political influence. In sum, private firms can use political strategies to compensate for a lack of institutional protection from both public and private expropriation hazards.

Firms' incentives to use political strategies to alleviate expropriation hazards are not equal: firms with greater market capabilities reap greater economic gains from reducing expropriation hazards and thus have higher incentives to pursue hazard-reducing political strategies than less capable firms. In this context, market capabilities refer to a firm's ability to succeed in competitive markets. Thus, a firm with greater market capabilities does not necessarily exhibit superior current performance, but it must have the potential to achieve greater future performance by removing expropriation hazards. Firms closer to the production frontier, for example, may not exhibit superior current performance if the expropriation hazards curtail their incentives to produce and invest; however, in a market supported by effective institutions, those same firms would generate greater value. Market capabilities can come from an initial endowment that a firm inherits at its inception, or they may be generated by successful strategies in the market.

Higher market capabilities lead to a greater need to use political strategies and activities to safeguard firms from expropriation hazards for several reasons. First, greater market capabilities imply that the latent value of assets at risk of expropriation will be higher. As such, the marginal return associated with a reduction in expropriation hazards will be higher for more capable firms than for less capable firms. For example, all else being equal, a more efficient manufacturer produces more output from a given asset base than less efficient manufacturers. Thus, a decrease in the risk of expropriation of the firm's assets leads to greater value retained by the more efficient manufacturer. In other words, if one thinks of the market returns from doing business absent expropriation hazards as the opportunity cost of operating in an institutional environment with these hazards, then the opportunity cost is higher for firms with greater market capabilities. Moreover, because some types of market capabilities generate greater quasi-rents, the quasi-rents reduce the firm's bargaining power vis-à-vis the government and further increase the future value at risk of expropriation (Williamson, Reference Williamson1996). These arguments imply that a more capable firm obtains a higher return from investing in political strategies that reduce expropriation hazards. In short, because employing political strategies to reduce the hazards of expropriation safeguards the firm's value created in the marketplace, the value of such political strategies is positively correlated with the market value that the firm expects to create in the marketplace and is thus greater for those firms with greater market capabilities.

In addition, firms with superior market capabilities likely face higher probabilities of expropriation, which would further contribute to a positive relationship between firms' market capabilities and their use of political strategies. Firms with greater market capabilities may be more lucrative objects of state predatory behavior because of their higher earning potential. Another reason why firms with greater capabilities may face a higher probability of expropriation is that they are more likely to explore new business opportunities, such as investment and innovation in new market sectors. The absence of established practices or regulations in these new sectors coupled with continued broad government discretion further increases the risk of expropriation. Participants in the quickly growing Chinese software industry, for example, face rampant copyright infringement because enforcement of intellectual property rights lags far behind industry growth (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2005). Furthermore, in exploring new business opportunities in different administrative locations or industry sectors, more capable firms face a greater number and variety of government bureaus, which expands their exposure to potential public expropriation. Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The greater the market capabilities of a firm, the more likely it will be to pursue political strategies to reduce the hazards of expropriation.

However, I do not deny that some firms in developing countries may also use political strategy for DUP purposes – to seek refuge from competition, which is a phenomenon that is similar to those observed by many studies in developed countries. I make two points about the implications of having both DUP political activities and value-creating political activities co-existing in an emerging economy. First, using political strategies as a substitute for market competition yields a negative relationship between firms' market capabilities and their political strategies (e.g., Lenway et al., Reference Lenway, Morck and Yeung1996; Morck et al., Reference Morck, Sepanski and Yeung2001), which makes it more difficult to find support for the positive relationship posited above. Any empirical evidence of a positive relationship between firms' market capabilities and their political strategies would indicate that the theory positing the negative relationship is not more predominant than the theory proposing the positive relationship between market capabilities and the hazard-reducing political strategy.

Second, because the expropriation hazard drives firms to use political activities that create value, the institutional context that generates these hazards is a critical factor. Thus, we may reasonably anticipate two consequences to emanate from institutional contexts characterized by expropriation hazards. First, because the risk of state expropriation is particularly strong in the private sectors of many emerging economies (such as the private sector in China), it is likely that, in an emerging economy, the value-creating motivation driving the positive association between market capabilities and political activities (H1) will dominate the negative association between market capabilities and political activities resulting from DUP motivation. Second, as state expropriation hazards become more pronounced in certain institutional contexts, there should be an even stronger positive association between firms' market capabilities and their use of political strategies. Thus, in the next section, I explore how the inter-provincial variation in multiple aspects of the market-supporting institutional environment in China may temper the relationship between market capability and firms' political strategies to reduce expropriation hazard.

Moderating Roles of the Institutional Environment

Political strategies are embedded in institutional contexts and may not be equally valuable to all firms. Because the benefit of political strategies in this context is predicated on reducing public expropriation hazards, it follows that the magnitude of the benefit (and, therefore, the incentives to engage in political strategy) will also vary with the expected level of expropriation hazards in a particular location. Moreover, the relationship between firms' market capabilities and their political strategies also depends substantially on the level of expropriation hazards in the institutional environment. The strength of the positive relationship between market capabilities and the benefits of hazard-reducing political strategies should increase with the significance of these hazards because the ‘gap’ between the marginal return of the political strategy of a more capable firm and that of a less capable firm widens in a more adverse institutional environment.

The first of these factors, the absence of checks and balances on the government, is a key institutional factor that leads to expropriation hazards. Greater checks and balances on a government's power constrain the government and its officials from expropriating a firm's private assets in general, such that the expropriation hazard is lower even if the firm has no political strategy. A lower relative level of expropriation hazard diminishes the need to use political strategies to combat the hazards of expropriation, particularly among the more capable firms. Therefore, the magnitude of the positive relationship between firms' market capabilities and their political strategies is smaller in locations in which governmental power is more constrained.

Hypothesis 2: The positive relationship between firms' market capabilities and their political strategies will be weaker if the location in which the firm conducts its business has greater constraints on governmental power.

Second, some governments may be concerned about the negative consequences of public expropriation (and the hazards of such expropriation) on the development of privately owned firms and therefore adopt more supportive policies to promote private sector growth and restrain bureaucratic predation. As discussed above, fiscal decentralization in China provides local and provincial governments with long-term incentives to pursue local GDP growth and to expand their tax bases, in addition to short-term revenue. Supportive local policies are, in effect, endogenous constraints on public expropriation and thus alleviate the need for more capable firms to use political strategies to protect their private assets.

Hypothesis 3. The positive relationship between firms' market capabilities and their political strategies will be weaker if the location in which the firm conducts its business has policies that are more supportive of promoting the growth of private businesses.

Third, the development of the legal system allows firms to resolve their disputes without having to resort to special political power. A formal legal system secures and protects private property, supports firms' market activities, and enables ordinary citizens and firms to seek justice against actions and activities that infringe on rights and property (e.g., Djankov et al., Reference Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2003). In locations in which the formal market-supporting institutional environment is more developed, firms with little or even no political power can effectively protect their assets from predation, which reduces the need to use political strategies to achieve this purpose. Therefore, capable firms pursuing political strategies to alleviate the hazards of expropriation will benefit less when their institutional environment features a higher than a lower quality legal system.

Hypothesis 4. The positive relationship between firms' market capabilities and their political strategies will be weaker if the location in which the firm conducts its business has a more developed market-supporting legal system.

METHOD

Data and Sample

The data used in the empirical analysis below are drawn from two sources. The primary source for firm-level data is a survey on Chinese POEs collected by the Privately Owned Enterprises Research Project Team (POERPT) in 1999. Additional province-level data come from the National Economic Research Institute (NERI) Index of Market Development of Chinese Provinces (published as Fan & Wang, Reference Fan and Wang2001) and the China Statistical Yearbook. The POERT survey is based on a nationwide random sample of 3,073 Chinese POEs generated by a multi-stage, stratified sampling across all provinces and industries in 1999; because of missing values, the final sample included in the regression analysis is reduced to approximately 835 observations. The POERPT conducted direct interviews with the major owner of each sampled POE using a questionnaire. The POERPT consists of scholars from an array of governmental and nongovernmental organizations, and the survey is part of a national project that collects information from representatives of the Chinese private sector to help the central government make and implement more effective policies.Footnote [5] The data from this survey are appropriate for this study not only because they provide relevant information of a representative sample of Chinese POEs but also because the original aim of the survey is not to focus on POEs' political activities per se, but to collect information about various aspects of POEs' business operations. As a result, interviewer-induced biases related to firms' political strategies are less likely. The unit of analysis is the firm.

Measures

The dependent variable is Direct Political Participation, which is a dichotomous variable indicating whether the firm's owner is a deputy of either the Congress or the Conference.[Footnote 6,Footnote 7] Conceptually, firms' market capabilities do not equal their current performance, and it would thus be ideal to include a measure for production efficiency without any price element – such as how far away a firm is from the production frontier – but such information is not available in the data. Therefore, as a proxy for a firm's market capabilities, the independent variable, I used a common measure of operational efficiency, Asset Turnover Ratio (Sales/Asset), which captures the firm's ability to generate sales from a given asset base. The asset turnover ratio has long been used in accounting and finance to capture the firm's ability to generate sales from a given asset base, i.e., how successfully the firm uses its assets to generate revenue (e.g., Altman, Reference Altman1968); in addition, the asset turnover ratio has also been used in economics on firm productivity issues (e.g., Braguinsky, Ohyama, Okazaki, & Syverson, Reference Braguinsky, Ohyama, Okazaki and Syverson2013) and has been adopted frequently by management scholars (e.g., Cochran & Wood, Reference Cochran and Wood1984). I use an alternative measure of market capabilities, the firm's R&D intensity, in a robustness test (discussed later).

Measures of the quality of the market-supporting institutional environment in each province in 1999 are based on both the institutional indices in the NERI database (see Fan & Wang, Reference Fan and Wang2001, for details) and the POERT survey. First, two institutional indices measure governmental power in each province. Reduction of Government Interference is an index based on the level of bureaucratic red tape that creates opportunities for state predation. The NERI database constructed this variable based on a nationwide survey that asked firms to rank the importance of having to address issues with government officials in their business operations relative to other business tasks, and the firm-level responses were aggregated at the province level. As such, a higher value on Reduction of Government Interference indicates lower public expropriation hazards in a province (this variable was called ‘Overregulation’ in Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006). Another measure of the government's power is Political Constraint, an index compiled in the NERI database that is based on the percentage of nontax fees and charges in rural residents' annual income and then aggregated at the province level. The key assumption here is that the ability of the government (typically, the local government) to collect nontax levies from peasants is an important indicator of the checks and balances on governmental powers (Fan & Wang, Reference Fan and Wang2001). Such fees and charges have been a major source of revenue for local governments and constitute the dominant financial burden of Chinese peasants, which has become a central issue exemplifying excessive fiscal predation by local governments (e.g., Yep, Reference Yep2004).

Second, I construct two variables based on the POERT survey to proxy the degree of policy support in the provinces. To construct Reduction of Unauthorized Levies, I first calculate the ratio of the amount of unauthorized levies divided by sales for each firm, then aggregate it at the province level by taking the mean value of the ratio for all the firms surveyed in each province; finally, I invert and standardize the index such that a higher value indicates lower expropriation in the province and, therefore, a more market-supportive institutional and policy environment. As the primary means by which local governments expropriate privately held assets, unauthorized levies consist of various ‘fees’ that are unlawfully charged to firms by local governments.Footnote [8] The second index measuring the policy environment is Reduction of Tax Levies, which is calculated in the same way as above except that the amount of total tax and authorized fees (the levies that firms are legally obligated to pay) is used. A higher level of Reduction of Tax Levies indicates lower tax burdens and, therefore, a more market-supportive institutional and policy environment.

Third, Legal and Market Services and Business Law Enforcement are two composite indices compiled by the NERI dataset that measure the development of a market-supporting legal system. Legal and Market Services includes the sub-indices of the number of lawyers divided by the province's population and the number of accountants divided by the province's population. The demand for these professionals tends to increase as business law becomes more developed and more enforceable (this variable was called Legal Environment in Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006). Business Law Enforcement is constructed based on the number of business lawsuits filed in 1999 divided by the province's GDP, and the number of business lawsuits concluded in 1999 also divided by the province's GDP. A greater value reflects more frequent use of the legal system to support business activities. At the province level, I control for the development of each province's economy and private sector using Province GDP, Private Sector Industrial Output, and Private Sector Employment. I also include Reduction of Local Trade Protection, an index from NERI that measures firms' evaluations of a province's trade barriers, which is an important indicator of the policy environment of a province (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006).

Firm-level control variables include the firm's age, number of employees, taxes, average growth in the number of employees, and access to bank loans, in addition to the major owner's age, years of formal education, managerial experience (years), and political capital endowment (i.e., whether the owner formerly worked for the government or the Chinese Communist Party before starting the firm). At the industry level, I control for industry size and investment with three variables: Ind Inv in Capital Construction is the industry's total fixed asset investment in new capital construction (billions RMB), Ind Inv in Replace & Upgrade is the industry's total fixed asset investment in replacement and upgrade of existing asset (billions RMB), and Industry Total Employees is the industry's total number of employees (millions). Summary statistics and correlations are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations of study variables

Analysis: Empirical Models

I first estimated the probit models that relate a firm's probability of Direct Political Participation to the key market capabilities measure and a variety of controls. One of the necessary assumptions for valid inferences to be drawn from the model specified above is that the measures of market capabilities are not endogenously determined by the political participation decision. The performance-related Asset Turnover Ratio may indeed be an endogenous predictor of firms' political participation due to reverse causality: if deputies in the Congress or Conference are able to leverage their position to increase firm sales, then direct political participation may lead to an enhanced Asset Turnover Ratio. To address this potential endogeneity, I used an instrumental variables approach and a probit model with endogenous regressors for estimations involving the measure for Asset Turnover Ratio. In the current context, I utilized the significant variation among Chinese industries in terms of labor and capital productivity, profit rates, and value added (e.g., Bin, Reference Bin2008) – along with the high intra-industry correlation in these measures noted elsewhere (e.g., McGahan & Porter, Reference McGahan and Porter1997) – to instrument for firm-level Asset Turnover Ratio using the asset turnover ratio of all other firms operating in the same industry in different provinces. As expected, this extra-provincial industry average turnover ratio is a good predictor of Asset Turnover Ratio: in the first-stage results for regressing the endogenous variable of individual firms' Asset Turnover Ratio on the instrumental variable of extra-provincial industry average asset turnover ratio along with all other exogenous predictors from the second stage, the coefficient for the instrument is positive at a significance level of 1%, and the F statistics reach 10, which is the commonly used rule-of-thumb (Staiger & Stock, Reference Staiger and Stock1997). It is also reasonable to assume that the performance of firms outside the province will not directly affect an individual firm's political participation decisions, particularly because political participation occurs at the provincial level or lower for over 99% of the firms participating in the sample. To test the interaction effect on Asset Turnover Ratio, I again adopted a standard instrumental variable approach and use the extra-provincial industry average asset turnover ratio and its interaction with each institutional index to instrument for the two endogenous variables in a two-stage least squares model (Blank, Reference Blank1991).Footnote [9]

RESULTS

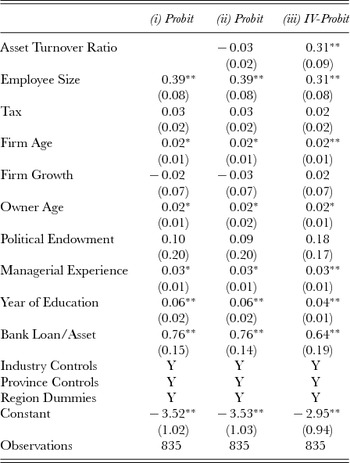

As the baseline for the moderating effect, Table 2 reports the estimates of the probit model and the instrumented probits and links the probability of direct political participation to firms' asset turnover ratio (a measure of market capability). The results indicate that firms with higher operational efficiency – measured by Asset Turnover Ratio (market capability) have a greater propensity to engage in direct political participation. Column (i) presents a model with control variables only, and the variables of interest are added in subsequent columns. In a probit model reported in Column (ii), the coefficient on Asset Turnover Ratio fails to be statistically significant (p < 0.01), whereas in a two-stage probit model using the extra-provincial industry average asset turnover ratio as an instrument for the firm-level variable Asset Turnover Ratio (Column (iii)), the coefficient on Asset Turnover Ratio is positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05), and an increase of Asset Turnover Ratio from its minimum to its maximum (the predicted value of Asset Turnover Ratio in the first stage) results in a 41.71% increase in the probability of Direct Political Participation. A Wald test of exogeneity rejects Asset Turnover Ratio as exogenous (p < 0.05). Although firms with lower market capabilities may also use political strategies as a substitute for competing in the marketplace, the positive and statistically significant relationship between market capabilities and political participation suggests that using political strategies to alleviate the hazards of expropriation is particularly (more) prevalent among firms of greater market capability. These results corroborate H1.

Table 2. Baseline H1: Market capabilities (Asset Turnover Ratio) and political participation

Notes:

•Industry-level controls include Industry Investment in Capital Construction, Industry Investment in Replacement & Upgrade, and Industry Total Employees.

•Province-level controls include Province GDP, Private Sector Industrial Output, Private Sector Employment, Political Constraint, Legal and Market Services, Reduction of Tax Levies, and Reduction of Local Trade protection.

•Clustered standard errors in parentheses.

•* significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; and *** significant at 1%

•In Model (iii), the instrumented variable is Asset Turnover Ratio, the instrumental variable is the extra-provincial industry average asset turnover ratio.

The results of testing the interaction effects of H2, H3, and H4 on the relationship between Asset Turnover Ratio and Direct Political Participation are reported in Columns (i) to (vi) in Table 3. Columns (i) and (ii) show the results for the moderating effects of the two institutional indices that measure the constraints of government power on Asset Turnover Ratio. In Column (i), the main effect of Asset Turnover Ratio is positive and significant, and its interaction with Reduction of Government Power is negative and significant; in Column (ii), the main effect of Asset Turnover Ratio is again positive and significant and its interaction with Political Constraint is negative and significant. These results indicate that the positive relationship between a firm's market capability and its political participation is weaker in provinces in which the government's discretion and power is more restrained, which is consistent with H2.

Table 3. Moderating hypotheses (H2 to H4): Institutional context on market capabilities and political participation

Notes:

•The following variables were not reported to save space but are available upon request: firm-level control variables include Employee Size, Tax, Firm Age, Firm Growth, Owner Age, Political Endowment, Managerial Experience, Year of Education, and Bank Loan/Asset; industry-level control variables include Industry Investment in Capital Construction, Industry Investment in Replacement & Upgrade, and Industry Total Employees; and province-level control variables include Province GDP, Private Sector Industrial Output, Private Sector Employment, and Reduction of Local Trade protection.

•Clustered standard errors in parentheses.

•* significant at 10%;* * significant at 5%; and *** significant at 1%

Columns (iii) and (iv) in Table 3 report the results of the interaction effect of the institutional indices that measure the policy support of the private sector and Asset Turnover Ratio. The moderating effect of Reduction of Unauthorized Levies on Asset Turnover Ratio is reported in Column (iii), and the moderating effect of Reduction of Tax Levies on Asset Turnover Ratio is reported in Column (iv). The interaction terms are both negative and statistically significant, which indicates that the positive relationship between Asset Turnover Ratio and political participation is weaker in provinces that extract less from private firms either in terms of unauthorized levies or in terms of tax levies, which supports H3.

Columns (v) and (vi) in Table 3 report the results from the test of the interaction effects of the institutional indices that measure the development of the legal system and Asset Turnover Ratio. The interaction of Legal and Market Services and Asset Turnover Ratio is negative and significant in Column (v), and the interaction of Business Law Enforcement and Asset Turnover Ratio is negative and significant in Column (vi); both of these results indicate that firms with a stronger market capability (higher level of operations efficiency) are less likely to pursue political participation in provinces in which the formal legal system is more established, which is consistent with H4.

Finally, Column (vii) includes all interaction terms. The coefficients of some interaction terms fail to be statistically significant – possibly because of multicollinearity. The VIF of the full model is 15.98, which is larger than the commonly recommended thresholds of 5 or 10. As a result, the full model becomes less relevant to interpretation, and researchers must focus on separate models of the interaction effects.Footnote [10]

These results show that, in general, firms' market capability (operational efficiencies) is positively related to firms' propensity to engage in direct political participation. Moreover, the positive relationship tends to be weaker in provinces with more effective constraints on governmental power, with more supportive policies that promote private sector growth, and with more developed formal legal systems.

We also note that the coefficients of the control variables are consistent across all columns and are also of interest (based on Table 2). Firms that are larger, older, pay more taxes, and have a higher bank loan to asset ratio are more likely to participate in the Congress or the Conference, as are owners who are older, more experienced, and more educated. Political Endowment is not a statistically significant predictor of direct political participation, which may result from two competing effects: on the one hand, private entrepreneurs who formerly worked for the government or the Communist Party may face lower expropriation hazards simply by dint of their prior connections, which would reduce the incentives to seek a deputy position; on the other hand, they may also have easier access to deputy positions in the Congress or the Conference.

Robustness Checks

An alternative reason that might contribute to a positive association between firms' market capabilities and their political activities is that governments may facilitate the political activities of certain favored firms. For example, along with Chinese private entrepreneurs actively participating in the political system, both the Chinese Communist Party and the various levels of government have considerable influence in the election or selection of deputies to the Congress and/or the Conference (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006; Ma & Parish, Reference Ma and Parish2006), which makes participation in these political organizations easier for some firms than others. Driven by the developmental side of the ‘dual incentives’ – which refers to the governments' incentives to both expropriate firms for short-term gains and to protect firm value so that the firms could contribute to fiscal revenue in the longer term (Ang, Reference Ang2010; Jia & Mayer, Reference Jia and Mayer2015), governments are most likely to be attracted to private firms that are best positioned to generate immediate revenues and/or contribute directly to local GDP and employment (e.g., Cull & Xu, Reference Cull and Xu2005). If the various levels of government believe that firms with greater market capabilities meet these criteria, then they are more likely to make it easier or less costly for these firms to pursue political strategies, thereby contributing to a positive relationship between market capabilities and firms' political strategies.

Although this theory also predicts a positive relationship between market capabilities and political strategies, it would further predict that this positive relationship should be stronger – instead of weaker – in locations in which governments are more supportive of private businesses, as would be manifest in more effective constraints on public expropriation of firm properties, more favorable policies and stronger market-supporting legal systems. This is because more development-oriented governments should be more likely to facilitate the political participation of firms with greater market capabilities. This alternative theory would make it more difficult for us to find empirical support for H2, H3, and H4. Therefore, finding empirical support for these moderating hypotheses strengthen the inference that firms with greater market capabilities more actively pursue political strategy to alleviate expropriation hazards, particularly in regions that lack the market-supporting institutions to curb these expropriation hazards.

Second, to further address this concern, I conduct additional statistical analyses to examine how the market capability measures relate to the reported willingness to pursue seats in the Congress or the Conference among firms that do not already hold seats in these organizations. I constructed an alternative dependent variable of Willingness to Pursue Direct Political Participation based on a survey question that asked firm owners whether they would attempt to become a deputy of the Congress or the Conference to increase their political and social influence. I then re-ran the regressions in Table 3 using this alternative dependent variable on the subsample of firms that do not yet have seats in the Congress or the Conference. The results (available upon request) show that, among firms that currently do not hold any seat in the Congress or the Conference, those with higher Asset Turnover Ratio are more likely to report that they are attempting to obtain deputy positions (coefficient = 0.480, p < 1%).

I also use an alternative measure of a firm's market capabilities – R&D Intensity – which is the percentage of a firm's employees dedicated to R&D activities. Greater R&D capabilities may enable firms to produce higher quality products at lower cost, which would increase the firm's market value; many R&D investments may also generate greater quasi-rents. I used probit models to regress the likelihood of direct political participation on R&D intensity – in addition to other control variables and a simulation-based approach from Zelner (Reference Zelner2009) – to examine the interaction effect. The results are highly consistent with the hypotheses (available upon request): firms with higher-level R&D intensity are significantly more likely to pursue direct political participation, and this propensity is even stronger in provinces with more developed market-supporting institutions. I argue that R&D intensity suffers less from the concern that it is endogenously determined by the political participation decision than the asset turnover ratio. In general, the consistent and robust findings of R&D intensity as an alternative measure of firms' market capabilities provide additional support for the hypotheses.

DISCUSSION

This study investigates the relationship between entrepreneurial firms' market capabilities and entrepreneurs' political participation in the Chinese private sector. I found firms' asset turnover ratios in the Chinese private sector to be positively related to the entrepreneurs' propensity to engage in direct political participation. Moreover, the positive relationships are less prominent in provinces in which governmental powers are better constrained, public policies and institutions are more supportive of the private sector and the market, and legal systems are more developed.

This study points to an important yet largely neglected scope condition in theories of corporate political strategy. Previous studies undertaken in contexts in which strong market-supporting institutions are in place have generally described political strategies as a way of substituting for market competition, i.e., such strategies are considered to be employed by market laggards to protect themselves from the rigors of market competition (Lenway et al., Reference Lenway, Morck and Yeung1996; Morck et al., Reference Morck, Sepanski and Yeung2001). This study extends the theoretical scope of corporate political goals by focusing on another role of political strategizing in which firms attempt to use political strategies to gain protection against the hazards of expropriation. In this case, political strategies become complements to firms' market competitiveness. In contexts in which the hazards of expropriation are substantially more prominent than in more developed countries, such as in many emerging economies, stronger firms are predicted to be more active in investing in political capabilities.

This study contributes to a growing body of literature on firms' investments in fostering their political capabilities in emerging economies. Many emerging economies differ from developed countries in fundamental ways that shape firms' strategies and behaviors, particularly with respect to underdeveloped market-supporting institutions and the consequent political risks that characterize the business environment. Many prior studies have investigated how political risks and political uncertainties influence firms' market activities and the development of their political capabilities (e.g., Henisz & Delios, Reference Henisz, Delios, Ingram and Silverman2002; Henisz & Zelner, Reference Henisz and Zelner2005; Holburn & Zelner, Reference Holburn and Zelner2010). This study adds to that knowledge by focusing on the relationship between firms' market capabilities and their political capabilities in the context of a developing country.

In addition, this study contributes to the emerging literature on ‘integrated strategies’. Corporate political strategy is a form of corporate ‘nonmarket strategy’ that firms undertake in public policy arenas (e.g., Baron, Reference Baron1995) or as ‘government-oriented’ public relations strategies (He & Tian, Reference He and Tian2008). An active literature on corporate nonmarket strategy advocates the concept of ‘integrated strategy’, i.e., that nonmarket strategy should be integrated with market strategy to achieve overall competitive advantages for firms (Baron, Reference Baron1995, Reference Baron1997). Empirical research following this line of reasoning has provided evidence that the use of political strategy is related to market activities (e.g., Shaffer & Hillman, Reference Shaffer and Hillman2000). This paper further extends this body of research by arguing and showing that firms' political strategies are directly related to their market capabilities.

Finally, this article adds to the literature that examines how the quality of the institutional environment affects the cost of doing business (e.g., North, Reference North1990; North & Weingast, Reference North and Weingast1989) and the variety of ways in which firms respond to the hazards generated by the institutional environment, such as by forming business groups, using relational contracting, leveraging personal networks, and pursuing political activities (e.g., Choi, Jia, & Lu, Reference Choi, Jia and Lu2015; Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu2000; McMillan & Woodruff, Reference McMillan and Woodruff1999). In the context of China, studies find that managers' social networks, particularly political networks, play an important role in shaping responses to expropriation hazards and firm performance (e.g., Li & Zhang, Reference Li and Zhang2007; Li et al., Reference Li, Yao, Sue-Chan and Xi2011; Luo, Reference Luo2003; Peng & Luo, Reference Peng and Luo2000). Building on the research that shows that Chinese POEs have different propensities for entering into politics in different provinces (Li et al., Reference Li, Meng and Zhang2006), I further explore how the level of development of institutional environments in different provinces moderates stronger firms' incentives to pursue political strategies in these provinces. This study's findings thus contribute to our understanding of why and how institutional environments matter in firms' operations in both market and nonmarket arenas.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations. First, the data do not provide a direct measure of the incentives for why a particular firm might develop its political capabilities, which, if available, would provide a more direct way to test the hypotheses. Instead, this study must rely on evidence of the net effect of two competing forces and moderating factors to obtain support, particularly for hazard-reducing political strategies. Another limitation is our consideration of only one political strategy, i.e., direct participation by the entrepreneur in one of the two most important political bodies in the country. Although we have confidence that this approach is one of the most important and prominent political strategies available to private entrepreneurs in China, there are other alternatives, most notably the development of informal private or personal relationships with government officials. Information on firms' investments in informal political connections would be useful to further corroborate the findings of the current study and to explore related topics, such as the relationships among a variety of feasible political strategies.

Although the data are from 1999, I believe that the insights developed in this paper continue to remain relevant. First, the key assumptions of the theory developed herein remain largely unchanged: the state's power does not face substantial checks and balances and the legal system is not sufficiently developed to protect firms from expropriation. In fact, the state has largely resumed, and even strengthened, its control of the economy (e.g., the World Bank recently called on the Chinese government to scale back its controlFootnote [11] ). As a result, firms continue to face substantial expropriation hazards that they must alleviate to safeguard firm value, such that the fundamental driver for using political strategies to shield the firm from expropriation—which also drives the findings in this paper – continues to persist. According to our theory, if the state faces fewer constraints on its power such that state expropriation hazards become more severe, then the positive relationship between firms' political strategies and their market capabilities will only persist – and may even have become stronger – during the years subsequent to 1999. Second, recent papers examining the political strategies of Chinese POEs continue to find that deputyships in the Congress or the Conference remain one of the most important political strategies (e.g., Jia, Reference Jia2014; Li & Liang, Reference Li and Liang2014). Moreover, beyond the context of China, examining these data from 1999 may help us assess corporate political strategies in other emerging economies that are at a similar stage of economic development and that are characterized by similar political regimes.

This study opens up interesting directions for future research. The proposed benefits of hazard-reducing political strategies featured in this paper rest on the premise that the institutional environment lacks high-quality and formal market-supporting institutions. Although the absence of such institutions is particularly prevalent in emerging economies, weak formal institutions may also characterize more developed economies, particularly in new sectors of the economy in which the development of laws and regulations lags behind industry growth and creates incentives for leading firms to take political action. In the U, for example, Google has recently engaged lobbyists to pursue action in the U Congress on issues such as network neutrality and online copyright protection.Footnote [12] Thus, whereas one must be somewhat cautious in generalizing the results of the empirical analysis beyond the context of China, I expect the theoretical arguments developed here to have a more general application. Another interesting future extension of the research would broaden the focus beyond local entrepreneurs to consider the strategic political options of foreign investors because political hazards in host countries affect multinational corporations' investment decisions (Henisz & Macher, Reference Henisz and Macher2004). This paper focuses on how local firms in a host country may reduce expropriation hazards through political strategies, and it would be helpful for future research to examine how multinational corporations respond differently to these hazards in host countries. Furthermore, it would be interesting to explore how political strategies affect the choice of which local firms these multinationals may seek as partners.

Practical Implications

This study also has practical implications. For example, multinational corporations from developed countries that are considering investing in emerging economies such as China typically face the tension of political uncertainties associated with excessive governmental power and weak protection of private property, including weak enforcement of property rights. Such firms must consider employing political strategies to protect against hazards that may not be relevant in their home countries that are characterized by developed institutional environments. Therefore, a firm's plan for geographic expansion must include deploying political strategies in ways that are different from what such multinationals are accustomed to in their home countries. For example, a strong multinational corporation might not have invested in political strategies to shelter itself from market competition in its home country, but as it expands overseas, it may discover a much greater need for political strategies in host countries for purposes other than seeking refuge from market competition. In addition, institutional environments in different locations within a single country may also vary significantly, as is shown in the case of China, which should also draw the attention of firms expanding into new geographic regions.

CONCLUSION

Research on political strategies pursued by firms in developed countries typically assumes that political strategies are unproductive and rent-seeking in nature in that they help less-capable firms to seek refuge to shield these firms from competitive forces. However, I argue that in emerging economies whose formal market-supporting institutions are underdeveloped – thus rifle with expropriation by the state and/or private parties, more-capable firms have a greater stake at risk of being expropriated, thus have higher incentives to use political strategies to protect their value from expropriation, which is a more productive use of political strategies. My analysis of privately owned firms in China indeed shows that, firms with greater market capabilities as measured by the asset turnover ratio and the R&D intensity are more likely to pursue direct political participation in key political organizations including the People's Congress and the People's Consultative Conference. Moreover, this pattern is particularly pronounced in provinces that have weaker market-supporting institutions – and thus greater risks of state and private expropriation. This paper contributes to the literature by showing that the nature of political strategies may not be exclusively unproductive and rent-seeking thereby attracting less capable firms, instead, they can be put to a more productive use by firms that are more capable in market competition. This conclusion suggests an opportunity for firms to integrate their market strategies with political strategies.