INTRODUCTION

International business scholars have intensified calls to critically examine business model innovation in transforming economies (Volberda, Van den Bosch, & Heij, Reference Volberda, Van den Bosch and Heij2017). A global business model is a holistic concept that depicts how firms create and capture value, achieving strategic fit across different types of business units, activities, or networks across borders (Aspara, Lamberg, Laukia, & Tikkanen, Reference Aspara, Lamberg, Laukia and Tikkanen2013; Teece, Reference Teece2010; Volberda et al., Reference Volberda, Mihalache, Fey and Lewin2017). MNEs are facing many challenges in innovating and implementing their business models due to the complicated coordinating processes and effective resource deployment in an extended global setting. The implementation of a global business model by MNEs is closely related to the management of headquarters–subsidiary relationships (HQS) because global business models are established on interconnectivity and synchronization between headquarters and foreign subsidiaries (Tallman, Luo, & Buckley, Reference Tallman, Luo and Buckley2018).

Previous research has highlighted the strategic role of the subsidiary (Birkinshaw, Holm, Thilenius, & Arvidsson, Reference Birkinshaw, Holm, Thilenius and Arvidsson2000), the management processes of MNEs (Chini, Ambos, & Wehle, Reference Chini, Ambos and Wehle2005), and the level of subsidiary autonomy and knowledge flows (Asakawa, Reference Asakawa2001). However, there is still limited understanding of how subsidiary managers manage and overcome the tensions between headquarters and subsidiaries when implementing global business models in transforming economies. Subsidiary managers carry into the MNE's network perceptual and decision-making abilities to construct boundaries between headquarters and customers/partners in the transforming economy (Wei, Samiee, & Lee, Reference Wei, Samiee and Lee2014). They contribute to translating, adapting, and acting on the MNE's global business model in contextually appropriate ways as well as enrolling actors in the global business network in ways that shape and make the markets (Lunnan & McGaughey, Reference Lunnan and McGaughey2019; Mason & Spring, Reference Mason and Spring2011). Thus, we address a key research question in this article: How do subsidiary managers of an MNE manage tensions between headquarters and subsidiaries when implementing the global business model in the transforming economy?

By addressing the above research question, this article makes two important theoretical contributions to the global business model literature. First, we have developed and critically explored a theoretical framework for uncovering how MNEs address the tensions that develop between headquarters and subsidiary managers in implementing global business models in transforming economies. We have extended the understanding of global business model implementation in the transforming economy to complement previous conceptual studies (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, Reference Baden-Fuller and Haefliger2013; Tallman et al., Reference Tallman, Luo and Buckley2018) and empirical research that mainly focuses on developed nations (Dunford, Palmer, & Benveniste, Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010; Khanagha, Volberda, & Oshri, Reference Khanagha, Volberda and Oshri2014).

Second, we have uncovered how the management of structural, behavioural, and cultural tensions by subsidiary managers enables MNEs to deal with the global integration-local responsiveness dilemma (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1998) more effectively when implementing global business models in the transforming economy. Tallman et al. (Reference Tallman, Luo and Buckley2018) suggest that the global business model thinking poses the question of how a firm operating in different countries can utilize just one global business model and the implications for integrating global competitive pressures into global business model thinking. Our findings demonstrate the usefulness of a global business model as a construct for analysing the practices used by subsidiary managers in implementing the MNE's global business model in a transforming economy.

Focusing on China as a transforming economy, we have not only extended the global business model literature by uncovering the tensions arising from the practice of global business model by subsidiary managers, but also looked into how these tensions can be overcome by MNEs. Our empirical evidence is based on a qualitative study of the subsidiaries of one leading Norwegian maritime MNE in China. China is a suitable transforming economy in this study because of the rapid development of the maritime industry and growing opportunities for MNEs. Its contrasting institutional profile, when compared with western countries (such as Norway), provides a relevant setting for examining challenges faced by MNEs (Couper, Reference Couper2019). Our findings reveal that the implementation of MNEs’ global business model in a transforming economy requires subsidiary managers to unpack a perceived rationally coherent global business model from the perspective of the headquarters.

The next section reviews the key literature used to analyse how subsidiary managers of MNEs manage the tensions and global integration-local responsiveness dilemma in implementing global business models, followed by the research methods. The empirical results, discussion of the findings, and conclusions are then presented.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Global Business Models of MNEs

This study analyses how subsidiary managers of MNEs in transforming economies manage tensions when implementing global business models developed in the MNEs’ headquarters (HQS). A business model offers ‘an analytical framework through which managers can seek to make sense of and share understanding between individuals, groups, and organisations of what the situation is in order to “work out” what is to be done’ in the market in which they are operating (Mason & Spring, Reference Mason and Spring2011: 1038). This sense-making and sharing of understanding during implementation introduces a practice-orientation, in which the creation of a model is a pragmatic activity involving adjustments that are based on the objective(s) to be achieved rather than the literal suitability of such adjustments (Ngoasong, Reference Ngoasong2010). The practice of a global business model involves both the headquarters and subsidiary managers undertaking different kinds of corporate versus business unit activities to achieve strategic fit across the MNEs’ global activities (Aspara et al., Reference Aspara, Lamberg, Laukia and Tikkanen2013; Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015). This subjectivity is drawn upon in our analysis to uncover the local responsiveness of MNEs’ global business model through examining the practices of subsidiary managers in a transforming economy.

Tensions in Headquarters–Subsidiary Relationships of MNEs

The dynamic change of HQS within MNEs has been attracting substantial research interest among international business scholars, for example, as seen in a recent review that identifies subsidiary roles and regional structures as critical to the success of MNEs’ international activities (Kostova, Marano, & Tallman, Reference Kostova, Marano and Tallman2016). As summarised in Table 2, the key literature reveals the structure and strategies, means of coordination and integration, as well as the organisation costs through HQS management (e.g., Lunnan, Tomassen, Andersson, & Benito, Reference Lunnan, Tomassen, Andersson and Benito2019). To achieve a balanced relationship, headquarters make decisions on the basis of an understanding of the cultural needs, organizational situations, and a shared organizational global vision, core values, and cultural principles by headquarters and subsidiary managers (Rodrigues, Reference Rodrigues1995). However, there are usually differences in the perceptions by headquarters (HQ) managers of western MNEs and their subsidiaries in a transforming economy, which can lead to poor relationships, conflicts, and ineffective relationships (Chan & Holbert, Reference Chan and Holbert2001). Toth, Peters, Pressey, and Johnston (Reference Toth, Peters, Pressey and Johnston2018) discuss structural, emotional, and behavioural tensions that arise during the implementation of large projects as causes of conflicts and poor relationships within MNEs.

Table 1. Summary of key global business model literature

Table 2. Summary of key literature regarding tensions in headquarters–subsidiary relationships

Thus, differences in perceptions and conflicts between HQ and subsidiaries as sources of tensions are relevant considerations for MNEs’ local responsiveness when implementing global business models in host countries (Tallman et al., Reference Tallman, Luo and Buckley2018). To understand and manage tensions, previous research has focused on subsidiary managers’ knowledge mobilizations that initiate lateral and bottom-up exchanges from HQ to subsidiaries (Tippmann, Scott, & Mangematin, Reference Tippmann, Scott and Mangematin2014). This notion of knowledge flows is also related to the dynamic capabilities perspective on HQS in transforming economies. Fourné, Jansen, and Mom (Reference Fourné, Jansen and Mom2014) identify three dynamic capabilities, including market sensing local opportunities, enacting global complementarities, and appropriating local value, which can help MNEs manage and operate successfully across emerging and established markets. However, it is important to address the tensions among these capabilities effectively. Managing tensions in a transforming economy also includes resolving HQ–subsidiary conflicts through increased communication, greater trust in the mutual capabilities, and deeper collaboration in confronting common challenges (Tasoluk, Yaprak, & Calantone, Reference Tasoluk, Yaprak and Calantone2006).

Role of Subsidiary Manager in the Practice of Global Business Models

The preceding review suggests that unpacking the role of subsidiary managers in the challenging HQS involves identifying a mixed-motive dyad, where interests and perceptions may not be completely aligned (Birkinshaw et al., Reference Birkinshaw, Holm, Thilenius and Arvidsson2000; Luo, Reference Luo2003). MNEs encompass both an internal environment and an external environment, which consist of customers, suppliers, competitors, and other stakeholders in both domestic and international markets (Andersson, Forsgren, & Holm, Reference Andersson, Forsgren and Holm2007; Birkinshaw, Hood, & Young, Reference Birkinshaw, Hood and Young2005). The role of subsidiary managers across host countries depends on the type of international strategy, the degree of headquarters’ control, and subsidiaries’ autonomy that vary across MNEs (Ambos, Andersson, & Birkinshaw, Reference Ambos, Andersson and Birkinshaw2010). Depending on their respective positions, subsidiaries usually possess deeper and more fine-grained knowledge about local markets in the host countries than headquarters because of their closeness to relevant market actors and institutions (Asmussen, Foss, & Pedersen, Reference Asmussen, Foss and Pedersen2013). This suggests that a headquarters–subsidiary perception gap may develop over time due to differences in the perception of challenges arising from different contexts. Linking this discussion about the role of subsidiary managers to the preceding review on the practice of global business models reveals two key steps for how global business models of MNEs can be appropriately adopted and implemented by subsidiary managers in transforming economies.

First, the role of subsidiaries in the practice of global business models can be uncovered in the decision-making processes that define HQS and how subsidiary managers clarify and adapt the core principles of global business models to achieve local responsiveness (Dunford et al., Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010). This is related to the global business model as both a cognitive and a linguistic schema. A business model can serve as ‘cognitive structures that consist of concepts and relations among them that organize managerial understanding about the design of activities and exchanges that reflect the critical interdependencies and value creation relations in their firms’ exchange networks’ (Martins, Rindova, & Greenbaum, Reference Martins, Rindova and Greenbaum2015: 105). However, over focusing on business models as schema can lead to inertia, as schemas tend to be self-reinforcing, guiding managers to ignore relevant discrepant information and data gaps in favour of more familiar or readily available information (Massa, Tucci, & Afuah, Reference Massa, Tucci and Afuah2017). This inertia can be addressed by considering the cognitive dimension (collective and individual) and the linguistic one (communicating within the organization), for example, through analysing the communicative interactions between stakeholders when implementing the global business model (Wallnöfer & Hacklin, Reference Wallnöfer and Hacklin2013).

Second, subsidiary managers need to understand and interpret the component parts of the MNE's global business model and the challenges in transforming economies. The changes undertaken by subsidiary managers to suit a specific host country context and the subjective discretions in which they interpret and make judgements may end up determining the final outcome of implementation processes (Hambrick, Reference Hambrick2007). In the context of the global business model, the outcome of decision-making processes includes adaptations to existing global business model principles, changes to the approach used to articulate key business model elements to respond to business opportunities, and/or deal with challenges in transforming economies. Here the role of subsidiary managers includes sensing and seizing local market opportunities (Fourné et al., Reference Fourné, Jansen and Mom2014; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, Reference Teece, Pisano and Shuen1997), creating and managing customer and supplier interactions systematically to improve market offerings, attract new customers, and respond to regulatory constraints in transforming economies (Dunford et al., Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010; Miozzo & Yamin, Reference Miozzo and Yamin2012). As higher-level intermediaries, headquarters, and subsidiary managers provide coordination across functional and geographical boundaries (Patriotta, Castellano, & Wright, Reference Patriotta, Castellano and Wright2013) by making knowledge sources available, connecting the parties to the transfer, and generating opportunities for knowledge exchange (Forkmann, Ramos, Henneberg, & Naudé, Reference Forkmann, Ramos, Henneberg and Naudé2017). However, there is little understanding of how this occurs during the implementation of global business models by MNEs.

The development, innovation, and implementation of global business models by MNEs require cross-border coordination and cooperation between headquarters and subsidiaries. It is inevitable that tensions will arise from time to time. However, there has been limited research on how MNEs deal with such tensions in the course of implementing global business models in the transforming economies with special focus on the role of subsidiary managers. This article extends the global integration-local responsiveness framework (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989) by not only theorising the tensions that MNEs face when implementing global business models in transforming economies (Fourné et al., Reference Fourné, Jansen and Mom2014; Toth et al., Reference Toth, Peters, Pressey and Johnston2018) but also showing how they are managed by subsidiary managers.

METHODS

Research Setting and Sampling

With the advent of falling global market shares and increased competition from low-cost shipbuilding and manufacturing firms in Asia and Latin America in the late 1970s, Norwegian maritime MNEs have responded by undertaking global business model innovation, switching from the development of customized vessels in Norway to the manufacturing of more standardized vessels by cooperating with external shipyards in transforming economies such as China (Amdam, Bjarnar, & Wang, Reference Amdam, Bjarnar and Wang2018). China is an appropriate transforming economy for this study because there are regulatory and cultural challenges for MNEs doing business in the country, in addition to developing one of the fastest-growing maritime industries in the world (Jia, You, & Du, Reference Jia, You and Du2012; Kynge, Campbell, Kazmin, & Bokhari, Reference Kynge, Campbell, Kazmin and Bokhari2017). Such a local context can be a trigger for the innovative practices of the global business model by the subsidiaries of MNEs.

We purposively selected one leading Norwegian maritime MNE, which has a high presence in China, for this study due to ease of access (Plakoyiannaki, Wei, & Prashantham, Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantham2019). The MNE entered the Chinese market in 2001 with an initial plan to establish a joint venture with a Chinese shipyard to build vessels based on its own designs. In 2005, it had similar observations in Singapore, Brazil, and several European countries. However, the business plan for China was not put into practice before any substantial investment was made. Afterwards, the headquarters of the MNE in Norway changed its overall international strategy from owning its own shipyards in the transforming economies to cooperating with local strategic partners. Its business activities in China are currently being carried out by its three wholly-owned subsidiaries engaged in marketing and after-sale services, maritime engineering, maritime equipment manufacturing, and shipbuilding with local strategic partners during the time period for our research.

Data Collection

The aim of the data collection process was to create rich accounts of subsidiary managers’ experience and knowledge on the practice of the MNE's global business model in the transforming economy, hence focusing on firm-specific documents and key informant interviews (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007). The documents mainly included annual reports and press releases published on the corporate website as well as the external news articles on the Norwegian maritime MNE's operation in the transforming economies in the trustworthy financial media such as Financial Times from 2011–2019.

Evidence arising from an in-depth case study can contribute to theory elaboration (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007) and provide new insights into the practices of the MNE's global business model in the transforming economy. We focused on senior managers at both headquarters and subsidiaries as key decision-makers with persuasive powers in ensuring the international success of the MNE's global business model in the transforming economy (Zhang, Dolan, Lingham, & Altman, Reference Zhang, Dolan, Lingham and Altman2009). We conducted thirteen in-depth, tape-recorded interviews at the MNE's subsidiary offices in China and headquarters in Norway during 2011–2013, each lasting about one or two hours (Table 3). The sample is such that senior executives ensure that the context of the MNE's global business model at both the headquarters and subsidiaries are incorporated in the analysis (Dunford et al., Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010) in a transparent manner (Aguinis & Solarino, Reference Aguinis and Solarino2019).

Table 3. Information on the interviews conducted

Informed by the themes developed in our literature review, the interview guide had two parts. In the first part, we focused on the strategic objective, structure, and operations of the global business model, including identifying the role of the subsidiary. In the second part, we drew on the responses from the first part to ask questions about the tensions and perception gaps between the managers at the headquarters and subsidiaries during the implementation of the global business model. The semi-structured format of the questions gave informants additional freedom to direct the interviews towards the themes that were of specific significance to the tensions in the course of implementing the global business model in China by drawing on their experiences. The interviews in China were organized and conducted by the Chinese author and the two Norwegian authors. The two Norwegian authors conducted the interviews in the headquarters of the MNE in Norway. The differences in any issues that arose were discussed and resolved among the research team to ensure reliable and relevant data analysis (Mihalache & Mihalache, Reference Mihalache and Mihalache2020).

Data Analysis

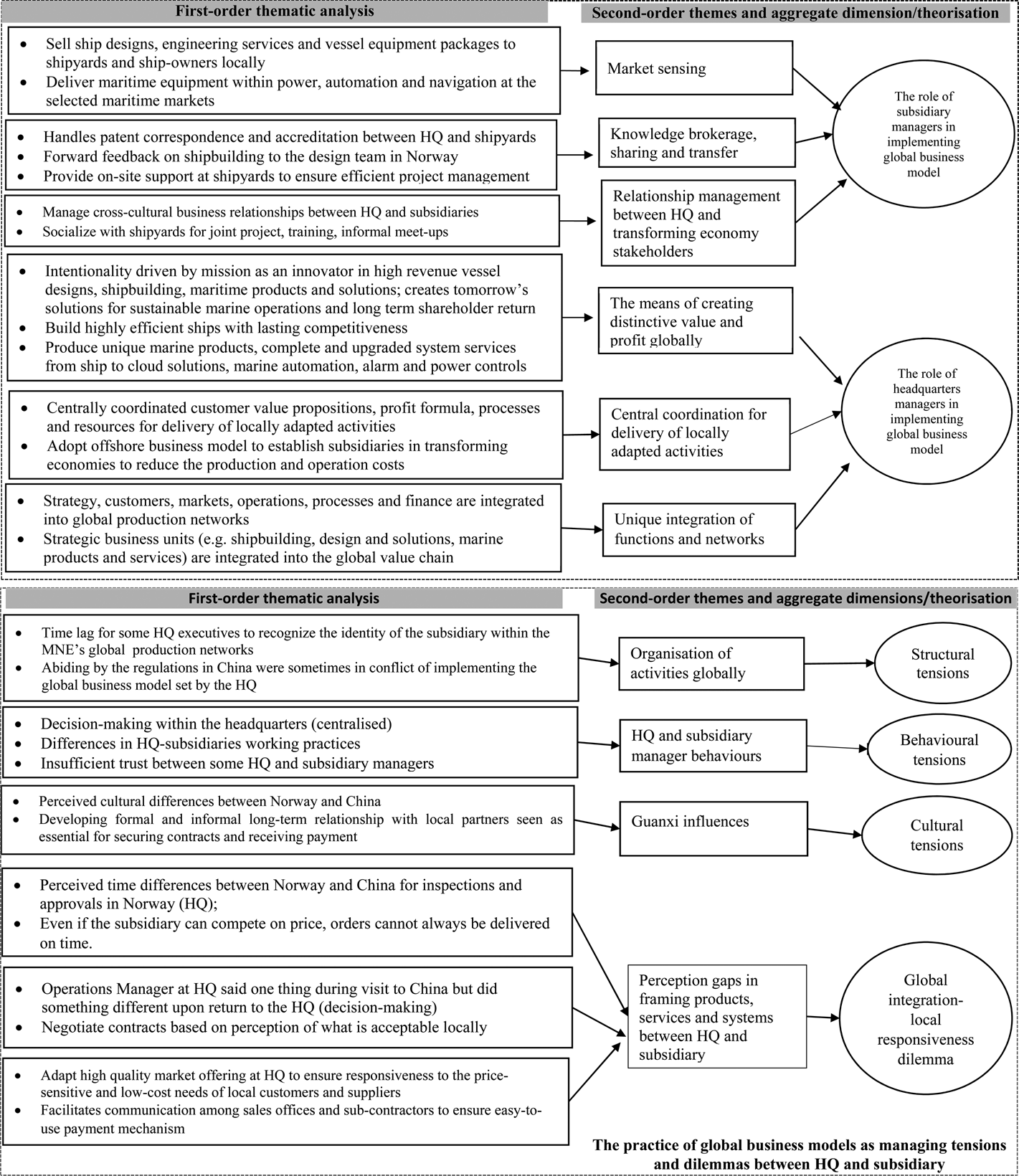

Given that this article aims at theory development rather than theory elaboration, this study adopts the Gioia data analysis technique (Gehman et al., Reference Gehman, Glaser, Eisenhardt, Gioia, Langley and Corley2018; Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). This method can be effectively used to analyse small samples because, instead of focusing on comparing a certain number of cases, it centres on eliciting a data structure composed of first-order, second-order, and aggregate dimensions based on theoretical sampling to stimulate theoretical insights (Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Then the transcribed data is ordered according to hierarchical categories representing informant terms, followed by themes, and subsequently aggregate theoretical dimensions (Aguinis & Solarino, Reference Aguinis and Solarino2019). Figure 1 provides a summary of our data structure.

Figure 1a. Data structure

The first phase consisted of identifying the first-order categories based on descriptive labels for the activities that interviewees reported and which we conceptualized during our analytical procedure as narratives about the global integration-local responsiveness dilemma, structural, behavioural, and cultural tensions in the practice of global business model by the subsidiaries of Norwegian maritime MNE in China. Through the documentary analysis and interview data, we identified the major component parts of the global business model of the Norwegian maritime MNE, from the perspectives of both the HQ and the Subsidiary in a transforming economy (China).

The second phase consisted of an iterative process to identify the constructs that were more abstract. Congruent with our literature review, analysis of the first-order categories revealed the component parts of global business models in the interpretations of interviews, which triggered the judgement of subsidiary managers when implementing the global business models in the transforming economy. The third phase consisted of identifying key theoretical dimensions emerging from the second-order constructs. For this, we undertook the analysis of the communicative interactions (Wallnöfer & Hacklin, Reference Wallnöfer and Hacklin2013) between the MNE headquarters and subsidiaries before aggregating to reveal the practices of MNE subsidiaries with respect to working with and managing the tensions with the headquarters in the process of implementing the MNE's global business model to ensure local responsiveness in the Chinese market. Finally, from the data structure (Figure 1), we condensed the relationships between the key concepts into an emergent theoretical framework (Aguinis & Solarino, Reference Aguinis and Solarino2019; Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). Our findings are presented below.

RESULTS

Global Integration-Local Responsiveness Dilemma

For the Norwegian maritime MNE we interviewed, unpacking the inter-linked component parts of its global business model and the communicative interactions between the headquarters and subsidiary managers revealed the complexities that come into play during the implementation process (Figure 1). The value propositions emphasise the product-service offerings. A fully integrated global business model enables the MNE to protect its product-service offerings because the configuration ensures that each business partner can contribute to the value creation through its global production networks, including shipyards, ship owners.

By expanding into transforming economies in Europe, Asia, and Latin America, the Norwegian maritime MNE is able to build more standardized vessels at a lower cost by using external shipyards than at its home shipbuilding base in Norway, thereby ensuring that the subsidiaries contribute positively to the MNE's value creation (Amdam & Bjarnar, Reference Amdam and Bjarnar2015). To establish a local presence while maintaining global integration, the subsidiary implements the MNE's global business model by acting as an agent and knowledge broker to facilitate the value creation, delivery, and capture in the transforming economy. This includes negotiating contracts that are signed between the headquarters in Norway and shipyards (value creation), manufacturing and supply of maritime equipment (design and technology), sales of maritime know-how and solutions (value delivery), and ensuring lower production and operation costs (value capture) in China. The CEO at the headquarters in Norway captured this vividly as follows:

What we do in China follows our international strategy of using partner yards, and we coordinate what we should do in Norway, Brazil, China, and other places. We have people on-site who control that these things are done.

However, when entering transforming economies in Europe, Asia, and Latin America, the Norwegian maritime MNE faces the global integration and local responsiveness dilemma like other western MNEs (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1998). Our data revealed a typical dilemma where the Norwegian maritime MNE's value creation focuses on high revenue designs and highly-efficient vessels that can be more expensive when compared with those produced in the transforming economies. The Director of Engineering in China commented as follows:

…Then they don't have the connection to the market. Some of the products in Norway is top of the art, state of the art products, but it has been engineered or produced by our engineer and the engineers like technical features. I feel that the link between the developer product and the market has been gone.

The above quote reveals that it is important for the headquarters in Norway to consider some adaptation of state-of-the-art products to meet the local needs of transforming the economy under the global business model due to contextual factors. Perception gaps can constantly arise between the headquarters in a western economy and the subsidiaries in a transforming economy. Therefore, the headquarters needs to keep in close touch and communication with their subsidiaries in the transforming economy because the subsidiary managers can keep sensing the local market and contribute to seizing on local business opportunities (Dunford et al., Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010; Teece, Reference Teece2010). In addition to dealing with the global integration–local responsiveness dilemma, our data shows that subsidiary managers should manage structural, behavioural, and cultural tensions between the headquarters and subsidiaries effectively to ensure the successful implementation of the MNE's global business model.

Structural Tensions

Structural tensions arise from the organization of global business activities and global network governance between the headquarters and subsidiaries of MNEs (Fourné et al., Reference Fourné, Jansen and Mom2014; Toth et al., Reference Toth, Peters, Pressey and Johnston2018). In order to reduce production costs and improve integrated product-service offerings to clients, the Norwegian maritime MNE set up a second subsidiary in Ningbo City, East China in 2007, and appointed a Norwegian subsidiary manager in May 2008. This is related to value creation and the need to sustain value capture over the long term (Tallman et al., Reference Tallman, Luo and Buckley2018). The subsidiary manager had rich work experience as a highly-skilled engineer for different multinational maritime firms in Norway. There were about 40 employees in the subsidiary in 2011, which mainly produced maritime electrical equipment for the headquarters in Norway, accounting for about 70% of its total output. Meanwhile, the subsidiary was also responsible for making procurement of maritime components from local companies in China for the headquarters.

Structural tensions emerged when a subsidiary manager found that it took some time for the headquarters to recognize the identity of his subsidiary within the global production networks of the MNE. He even supposed that one of the main reasons why the headquarters had ignored the subsidiary was because the Chinese subsidiary did not have a competitive position within the MNE's global production networks. From an HQ manager's perspective, a competitive position is important for realizing value creation, and setting up a production unit linked to the MNE's global production networks (Lunnan & McGaughey, Reference Lunnan and McGaughey2019) facilitates the value that can be captured (Mason & Spring, Reference Mason and Spring2011). The subsidiary manager of the production unit in Ningbo City, China, made the following comment in the interview:

Didn't have the support, it was not planned, it was not…, most people didn't know about this factory the first year. How can they use this factory, how can they know how to use this factory if they don't know it's here?

As the business grew, the subsidiary manager and his colleagues gradually developed their knowledge about the local market and established more business relationships with local clients in China. This is related to the knowledge search and transfer role of subsidiary managers (Tippmann et al., Reference Tippmann, Scott and Mangematin2014) in the sense that they initiate additional lateral and bottom-up exchanges, locally with Chinese partners and internationally with HQ managers. The new interactions also facilitated their market sensing role in that continual interactions increasingly urged them to explore new business opportunities in the transforming economy, which did not directly align with the global business model of MNE. This resulted in structural tensions between the subsidiary and the headquarters, as indicated by the subsidiary manager of the production unit in Ningbo City, China:

I hope so because then we remove one link, and if we cannot sell the design to a shipyard or ship owner, maybe they want to buy a Rolls Royce design, or maybe other local design on the vessel; then we can supply the power package to them directly. Now, we cannot do that. That's decided by the board of this company. This is where I'm trying to use my politics now!

Regarding the seizing of local business opportunities, the subsidiary manager of the sales and engineering unit in China stated clearly in the interview that he would like to challenge the global business model that the headquarters was implementing. He showed his intention to target new ship owners directly:

It will on the global but we are also targeting foreign ship owners that build vessels here in China because then we can have a different approach, instead of going directly to the shipyard, we can persuade the ship owner, we can tell them that ‘you have to tell the shipyard that you want only this product from (the name of MNE), you don't want anything else because of the quality of something.’ Then, they can tell the shipyard ‘we want the product from them’. Then we can deal with the shipyard directly.

The above quotation is related to perception gaps in the sense that whereas a headquarters' perspective might suggest a rational decision-making process for negotiating a contract (Lunnan et al., Reference Lunnan, Tomassen, Andersson and Benito2019), the subsidiary manager adopts a pragmatic approach in negotiating a contract based on its perception of what is acceptable within the local business environment. The contradiction between rational and pragmatic decision-making is related to structural tensions, which are organizational in nature (Fourné et al., Reference Fourné, Jansen and Mom2014).

We also find that subsidiary managers must abide by local regulations in China, which were sometimes in conflict with implementing the MNE's global business model set by the headquarters. The interview data reveal an additional consideration, namely the time it takes to complete transactions given the institutional complexities in the transforming economy. This is captured in the following quotation by the Norwegian general manager in China:

In Norway, they can have, they can do a DNV [a classification company] inspection on a switchboard after two to three days. You deliver the drawings for approval, the DNV, and then after two to three days, they can be at the factory and delivery inspection. Here in China, they do the approval in Shanghai. They told us they need 40 days! We have a disadvantage. For some orders, even if we can compete on price, it doesn't matter because we cannot deliver on time.

The above empirical analysis indicates that subsidiary managers need to deal with structural tensions when implementing global business models in transforming economies. However, their roles in sensing local business opportunities contribute to resolving the structural tensions by integrating the subsidiaries’ local responsiveness requirements in the transforming economy into the MNE's global production networks, despite facing institutional complexities.

Behavioural Tensions

Behavioural tensions occur within MNEs when decisions are mainly made by the managers at the headquarters. We see this in the implementation of the global business model by the MNE in the transforming economy (Figure 1). Though it has a global focus without considering country-specific factors fully in the transforming economy, the framing of the component parts allows the subsidiary managers to be able to interpret and judge what adaptations might be needed in a specific transforming economy. This was typified by the Norwegian maritime MNE in the study, where its subsidiary had not been fully informed of the strategy made at the headquarters about manufacturing maritime equipment in China, as remarked by the subsidiary manager of the production unit in China.

It was decided on board level of the group but not taken further down in the organisation [to the subsidiary]. We had to learn from Danish companies that are here in China. They have a much more open strategy. I met [names withheld], and on their side, when they presented their organisation and factory in China, it is written that within two years, all production will take place in China. This was not written anywhere in [our company]. [But we said to ourselves] After some time, maybe this product will have to be produced in China.

The above quotation is related to the knowledge brokerage role in that communicative interactions are made by subsidiary managers to interpret elements of a global business model as the basis for making judgements about the feasibility of a value proposition and legitimising the actions to take in response (Wallnöfer & Hacklin, Reference Wallnöfer and Hacklin2013). The different working practices between the headquarters and subsidiaries can also result in behavioural tensions due to the lack of trust, as remarked by the subsidiary manager:

It's a little bit of that as well but especially the production manager and the manager for the operation in the headquarters. They have said one thing and then done a totally different thing. This I've seen many times when they've been here. And they have been here quite many times, and everything is like sunshine and ‘oh yeah, here we are going to do some businesses. As soon as they go back to Norway, which is changed.

The decision-making is usually centralized within the Norwegian MNEs, which is another source of HQS tensions because the subsidiary manager usually hopes to have more autonomy to implement the global business model in the transforming economy. There is a perception gap arising from differences in the behavior of the subsidiary managers vis-à-vis the headquarters managers, which influences decision-making. Here, the relationship management by subsidiary managers becomes crucial, as stated in the below quotation by the Director of Marketing in China in the interview:

It is, but of course, there is where I should use my politician skills, which I don't have! I am a little bit too open, speak a little bit too open and too straight forward sometimes. When you come up to the level where I am now, you sometimes must be a politician to do some lobbying and things like this. I have something to learn here.

In addition, the interview data indicate that it usually takes a much longer time for senior managers at the headquarters to initiate change in global business models than the subsidiary managers had expected, which led to the tensions. This was typified in relationship management, evidenced in accounts of how the subsidiary manages relationships with the headquarters to facilitate value delivery and value capture (e.g., Dunford et al., Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010). For example, the Director of Engineering in the subsidiary of Shanghai City, East China, made the following comment:

when you settle down, you need to write down what is your product and how to build this product, how to produce it, how to maybe improve this product but anyway you have to write down everything, get all the heads in Norway, squeeze them, get it on the paper and then you can start to produce here because it takes, it will take you a very, very long time, I told him if you are going to do it the Norwegian way. And, actually, here in China, the Chinese government they are not so patient, so after two years you should have positive results.

The above analysis indicates that the factors leading to the behavioural tensions of the MNE include the centralisation of decision-making within the headquarters, lack of trust, and different working practices between the headquarters and subsidiaries in the transforming economy. Subsidiary managers need to make effective relationship management with HQ to solve the behavioural tensions.

Cultural Tensions

The global business model of the Norwegian maritime MNE emphasizes the close involvement in the whole shipbuilding processes in transforming economies. In practice, the subsidiary manager acts as an important knowledge broker to ensure value co-creation with its stakeholders in transforming economies. To reduce the possibility of perception gaps that can be associated with cultural tension (e.g., Lunnan & McGaughey, Reference Lunnan and McGaughey2019), local teams were set up on-site at the shipyards to ensure efficient project management and communication among the subsidiary, headquarters, shipyards, and ship owners. This is related to communicative interactions used by managers to interpret and act on business models (Wallnöfer & Hacklin, Reference Wallnöfer and Hacklin2013). This had to do with the fact that the MNE cooperated with local shipyards in transforming economies. Meanwhile, the MNE's shipyard in Norway also played an important role in contributing to its design success and providing the shipyards and its business partners in the transforming economy the opportunities to visit the shipyard and headquarters in Norway to experience the innovative new-generation of vessels that were being designed and constructed. The Manager of Sales and Engineering Unit in China made the following comment in the interview:

In China, we have staff at the shipyards for all vessels under construction, providing sourcing support and feedback on construction, which we forward to the design team in Norway. There is direct communication every single day. So, you can see the bridge, but there is also a filter. A lot of the patent correspondence is handled by us. We filter everything and provide a draft of what type of design, equipment, or solution is needed.

The above quotation about daily communication is related to the knowledge brokerage role of subsidiary managers, seen as important for facilitating the connecting of formal and informal knowledge search and transfer mechanisms across functional and geographical boundaries of MNEs (Patriotta, Castellano, & Wright, Reference Patriotta, Castellano and Wright2013). This helps address cultural tensions in the sense that though the MNE operates a centralized global business model, the interview data shows that one of the Chinese subsidiary managers, who had been educated and worked in both China and Norway, plays an important role in orchestrating the local production networks in China and making effective cross-cultural management and communication by distilling the business information from cross-functional teams in China to the headquarters in Norway.

In addition, the guanxi network, which requires the informal building of trust to underpin effective business relationships, plays an important part in the marketing, sales, and delivery of maritime product-service offerings in China (Bu & Roy, Reference Bu and Roy2015). For example, the marketing manager of the Norwegian maritime MNE's subsidiary in Shanghai City needs to undertake effective management of the local guanxi network to transfer the tacit knowledge from the headquarters in Norway to the shipyards in China successfully.

Our analysis also reveals that the value creation approach emphasised by HQ managers illustrates how the MNE ‘builds a wide range of highly efficient vessels with lasting competitiveness’ and ‘to secure long-term shareholder return’. However, this comes into conflict with perceptions in China, where products and services are assessed on local prices and costs. This is related to customer sensing (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, Reference Baden-Fuller and Haefliger2013) role of the subsidiary managers as useful for managing cultural tensions by reacting to situations in which the customer does not display the expected reaction to the headquarters’ framing of products or services. A subsidiary marketing manager made the following remarks in the interview:

Our main customers are not Chinese ship owners but build vessels in China. The only thing that seems they care about is the price. The cost of this. If you don't’ have a very good cooperation with the shipyard, if you are not friends with them, then you can never get a contract here because of the price, because we have a slightly higher indirect cost than other Chinese companies.

We see the above quotation is related to guanxi influences as subsidiary managers rely on informal friendships alongside formal interactions in building long-term relationships both as part of sensing what customers desire but also to market products and services. Through understanding the perception gap in the framing of products and services, the subsidiary is able to manage cultural tensions and help address the global integration–local responsiveness dilemma (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1998) that could have potentially had negative impacts on the MNE's revenue generation potential.

DISCUSSION

Theoretical Implications

When MNEs implement their global business models in transforming economies, different types of tensions can arise between the headquarters and subsidiaries, which need to be overcome to ensure that their products, services, and delivery mechanisms can be adapted to the needs of local conditions. In examining how the subsidiaries of one leading Norwegian maritime MNE practise its global business model in China, we have made the following two important theoretical contributions to the study of global business models of MNEs in transforming economies.

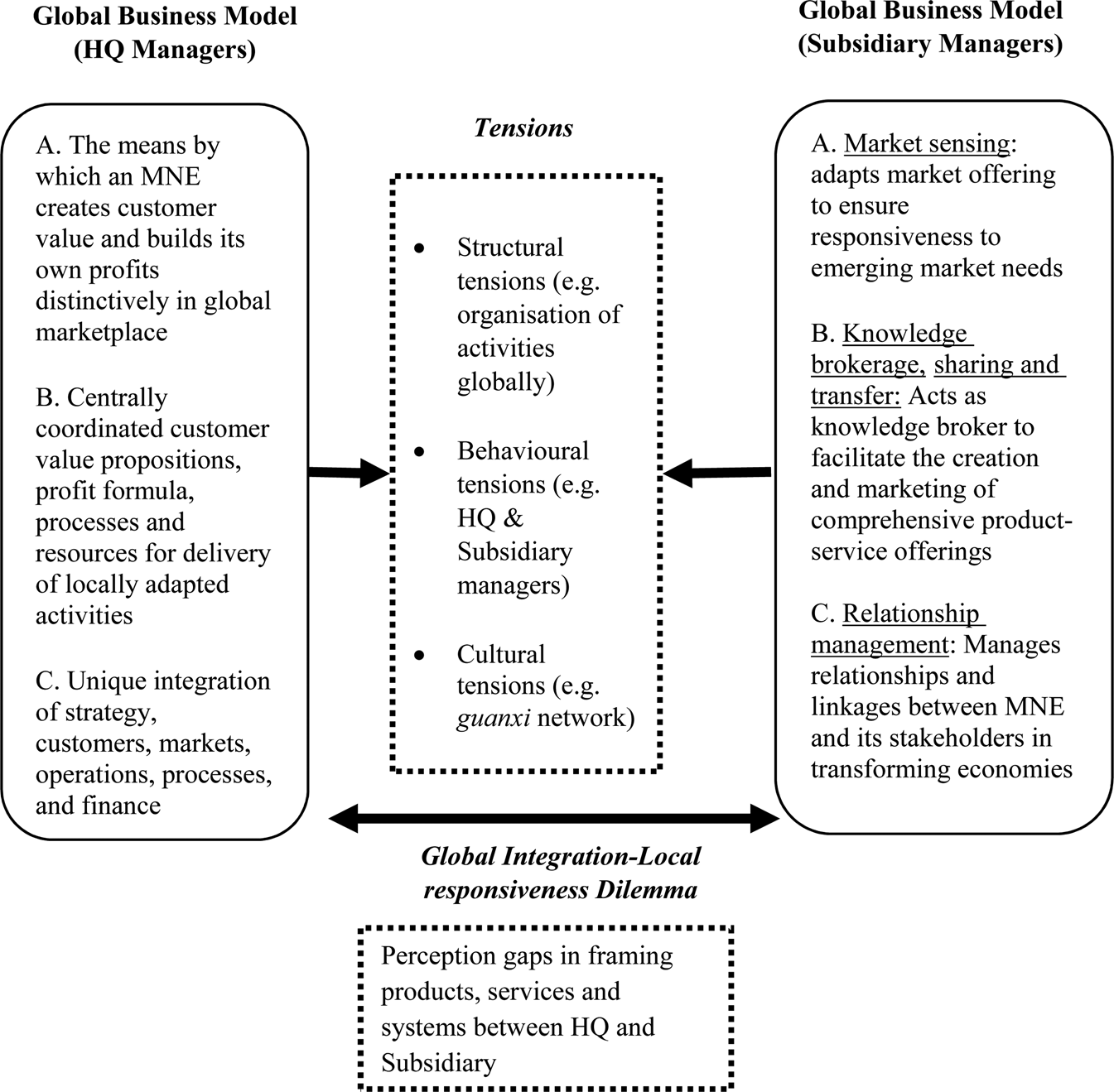

First, we propose a theoretical framework for understanding the practice of MNEs’ global business models in transforming economies, focusing on the role of subsidiary managers (Figure 2). The framework links the headquarters perspectives of the components of a global business model (left), the tensions between the headquarters in a western MNE context, and the subsidiaries in a transforming economy (middle), and the practices of the subsidiary managers in the transforming economy (right). The two-way arrow at the bottom of Figure 2 is the feedback loop to the headquarters, illustrating the global integration-local responsiveness dilemma (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1998). This dilemma is evidenced in the perception gaps between an MNE's headquarters and subsidiaries. The examples of perception gaps in our data include the use of ‘politics’ or ‘making friends’ as alternatives to rational decision-making by subsidiary managers, the alternative framing of product-service offering to secure buy-in from local partners in the transforming economy. Such examples illustrate how the practices of subsidiary managers (A, B, and C in the Subsidiary Managers box) combine with the headquarters perspective on tensions along with the response to the global integration-local responsiveness dilemma. Our findings show clearly that subsidiary managers need to un-pack in the transforming economy what might otherwise seem to be a rational, coherent global business model from the perspective of the headquarters.

Figure 2. Understanding the practice of MNEs’ global business model by subsidiary managers in transforming economies

The framework shows that subsidiary managers implement the MNEs’ global business model through understanding and managing the tensions between the headquarters based in a western country and the subsidiaries located in a transforming economy. Evidence of understanding and managing tensions have been uncovered through examining the communicative interactions (Wallnöfer & Hacklin, Reference Wallnöfer and Hacklin2013) that the subsidiary managers have with key stakeholders within the MNE's global business networks. For this, the subsidiary managers perform three key functions, namely market sensing, knowledge brokerage (sharing and transfer), and relationship management (see A, B, and C in the right column of Figure 2). Our emergent framework complements the existing literature on global business models of MNEs (e.g., Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, Reference Baden-Fuller and Haefliger2013; Tallman et al., Reference Tallman, Luo and Buckley2018) by addressing how MNEs operating in transforming economies can achieve local responsiveness by ensuring that subsidiary managers understand how to manage the tensions associated with the implementation of global business model.

For instance, by assessing that the clients in transforming economies of Asia and Latin America are price-sensitive and do not place quality as their core orientation, this is a challenge for the headquarters and subsidiary managers, who strive for local responsiveness (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Samiee and Lee2014). To deal with this global integration-local responsiveness dilemma, the subsidiary managers of the MNE were inspired by the adaptation of the ship design to a more ‘cost-effective design’ of tangible (ship design) and intangible (value for money) components. Thus, the subsidiary manager deals with global integration and local responsiveness dilemma (Bartlett & Ghoshal, Reference Bartlett and Ghoshal1998) by enlisting customers’ preferences and securing local buy-in. Chang and Park (Reference Chang and Park2012) explore how Chinese customers have become more demanding with both price and value important consideration in their choices of product and service offerings, a change requiring western MNEs in China to develop strategies that enable them to use market heterogeneity and technological complexity to become competitive. This suggests that the practice of global business models goes beyond, enabling MNEs to ‘select technologies and features to be embedded in the product and/or service’ (Teece, Reference Teece2010: 173). The in-depth case study in this article indicates that the subsidiary managers act as high-level knowledge intermediary (Patriotta et al., Reference Patriotta, Castellano and Wright2013) in the successful implementation of global business models in transforming economies.

Our second main contribution is that we have uncovered how the management of structural, behavioural, and cultural tensions by subsidiary managers enables MNEs to deal with the global integration-local responsiveness dilemma more effectively in the transforming economy. These tensions are consistent with those faced by MNEs that try to use globally-oriented and locally-focused capabilities simultaneously. For example, behavioural and cultural tensions mainly arise from mistrust between the headquarters and subsidiary managers. Structural tensions can result from managing multiple organizational sub-systems and the inherent organizational contradictions (Fourné et al., Reference Fourné, Jansen and Mom2014; Toth et al., Reference Toth, Peters, Pressey and Johnston2018). With respect to managing the tensions, our findings reveal it is important for subsidiary managers to communicate the value proposition to the local stakeholders effectively while aligning to the MNE's global business model requirements.

According to Baden-Fuller and Haefliger (Reference Baden-Fuller and Haefliger2013), many MNEs fail commercially in transforming economies because little attention has been given to adapting their global business models to the transforming economies properly. They need help to remedy market-specific challenges by their subsidiaries. To interpret and coordinate actions within an MNE's global production networks (Lunnan & McGaughey, Reference Lunnan and McGaughey2019), subsidiary managers act as knowledge brokers in that they keep sensing the local business environment in transforming economies and contribute to developing the strategic direction and global business model of the MNE. For example, the subsidiary manager is able to try something new or experiment (Dunford et al., Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010) by using alternative interpretations of existing product-service offering to enroll customers and suppliers in the transforming economy into the MNE's international business activities and strategies while keeping close communication with the headquarters.

With respect to knowledge transfer, knowledge sharing, and networking relationships (e.g., Asmussen et al., Reference Asmussen, Foss and Pedersen2013), our results reveal how the subsidiary managers act as ‘bridge’ and ‘filter’ interactions between the headquarters and stakeholders, which helps protect the MNEs’ core competencies in transforming economies. As a ‘filter’, the subsidiary interacts with both internal and external stakeholders in the transforming economy and sends to the headquarters only information that is consistent with the core principles of the MNE's global business model. This role of the subsidiary ensures that customers and suppliers in transforming economies primarily have contact with the subsidiary, and not with the headquarters, enabling the MNEs to protect their internalization advantages. The only exception to this occurred in situations where on-site subsidiary teams at the shipyards have a mandate to secure direct contact between headquarters and local business partners. This is crucial for protecting competencies when operating in transforming economies such as China, where market heterogeneity and technological complexity require broadening and deepening the local knowledge and relationships to enhancing the competitiveness of MNE (Chang & Park, Reference Chang and Park2012; Prashantham, Zhou, & Dhanaraj, Reference Prashantham, Zhou and Dhanaraj2020). While subsidiary roles can be defined by headquarters, our findings are consistent with the view that certain strategic choices should be available to subsidiaries beyond those provided by headquarters in transforming economies (Birkinshaw et al., Reference Birkinshaw, Hood and Young2005; Miozzo & Yamin, Reference Miozzo and Yamin2012). Therefore, we do not suggest that the practices of global business models by subsidiary managers in transforming economies can be similar to those in developed economies due to their specific institutional environments.

Managerial Implications

The empirical case study has provided practice lessons that can inform the headquarters-subsidiary interactions and activities for those MNEs that implement global business models in transforming economies. Subsidiary managers need to constantly undertake market sensing activities to adapt market offerings of MNEs to meet the needs of the transforming economy. To effectively manage the integration of the transforming economy into MNEs’ global production networks and the delivery of value co-creation with the local business partners, subsidiary managers act as knowledge brokers to facilitate the creation and communication of the value proposition to stakeholders, contributing to the successful implementation of the global business model of MNEs in transforming economies.

The business environment in a transforming economy such as China is constantly evolving and has a distinctive governance mechanism, which differs from that in the western developed countries considerably (Lewin, Välikangas, & Chen, Reference Lewin, Välikangas and Chen2017). To succeed in such a business environment, subsidiary managers of western MNEs in the transforming economy must understand and work with structural, behavioural, and cultural tensions along with the global integration-local responsiveness dilemma effectively. They need to be simultaneously cognizant of and engage in those practices which are most fit for the particular type of transforming economy stakeholders. For example, with respect to cultural tensions, the subsidiary managers should make effective cross-cultural management between HQ and transforming economies, understanding that cultural practices in a country such as China can often be judged moral grounds leading to negative influences, which may affect the performance of the subsidiary (Bu & Roy, Reference Bu and Roy2015). This understanding enables the subsidiary manager to better share and transfer knowledge, which is useful for facilitating the creation and marketing of comprehensive product-service offerings from the headquarters to satisfy the local needs.

Limitations and Future Research Opportunities

Our study has opened up two possibilities for future research. First, though we uncovered three tensions and link these to three roles for HQ managers in the implementation of business models, our data does not sufficiently allow us to assess whether all three roles are equally important for all tensions or whether some roles are more important in solving some tensions than others. Future quantitative research utilizing multiple case studies of HQS managers can build and strengthen our findings in this area. We believe our data does not sufficiently allow us to determine whether the roles are equally important for all tensions. We have recognised this as a limitation and suggested for future research.

Second, while we adopt the perspective of the MNE in implementing the global business model, the customers’ perspective in transforming economies is equally critical and important (Kristensson, Matthing, & Johansson, Reference Kristensson, Matthing and Johansson2008). This is relevant because value creation in the practice of the global business model is seen as a mutual co-evolving activity involving an MNE and its business network partners, such as suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders. Our discussion of the relationships among the headquarters, subsidiary, business partners, and clients require further enquiry in relation to the organizational and knowledge management challenges under global network architecture. The existing research on global business models of MNEs suggests that such relationships have implications for industry boundaries and industry evolution (Miozzo & Yamin, Reference Miozzo and Yamin2012; Teece, Reference Teece2010). Future research in this area can improve our understanding of relationship management in global business models implementation in transforming economies.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we have developed an empirically grounded theoretical framework for understanding how subsidiary managers of western MNEs manage the structural, behavioural, and cultural tensions between headquarters and subsidiaries along with the global integration- local responsiveness dilemma when implementing global business models in transforming economies. Our findings reveal how the subsidiaries of one leading Norwegian maritime MNE communicated the value of their market offering to convey both tangible and intangible elements and to do so in a way that reflects the strategic objectives of the headquarters and the responsiveness challenges of the host transforming economy.

However, it is not argued in this article that MNEs in the maritime industry are unique in terms of implementing their global business models. The cases of MNEs such as global retail banks (Dunford et al., Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010) or the recorded music industry (Mason & Spring, Reference Mason and Spring2011) also point to a global business model focus in responding to international competitiveness and local responsiveness. Our focus on the maritime industry complements and extends the existing literature by demonstrating how the practice of global business models by MNEs involves understanding and managing tensions between their headquarters and subsidiaries in transforming economies with special reference to China. More research using multiple case studies can clarify the conditions under which each of the three subsidiary manager roles contributes to solving each of the three tensions in our proposed framework.

Regarding our theoretical contribution around addressing the tensions between headquarters and subsidiaries of MNEs in the transforming economy, the literature mainly deals with the tensions as problems or challenges, but what we have shown is that the tensions can also be a source for innovation and change. Subsidiary managers may be innovative because they keep sensing and seizing local business opportunities while implementing global business models in transforming economies.