I. Introduction

In 2015, the United Kingdom engaged in a targeted killing operation against one of its citizens in Syria as part of its counter-terrorism campaign against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Reyaad Khan was killed in the first drone strike of its kind in an action that was officially taken in self-defence against an imminent threat in an area where the United Kingdom was not engaged militarily at the time. As then-Prime Minister David Cameron explained, this strike was a ‘new departure’ for the United Kingdom, which raised many questions from a variety of sources, including politicians, parliament, academic commentators and civil society groups.

The strike was not an isolated, single incident but can be seen as an important precedent for an emerging practice. As then-Defence Secretary Michael Fallon stated, ‘We wouldn’t hesitate to do it again. If we know there is an armed attack that is likely, if we know who is involved in it, then we have to do something about it … If we have no other way … than using a military strike to prevent it then that’s what we’ll do’ (Fallon, Reference Fallon2015). Similarly, a parliamentary inquiry into the strike concluded that ‘it is the Government’s policy to use lethal force abroad, outside of armed conflict … against individuals suspected of planning an imminent attack against the UK, as last resort, when there I no other way of preventing the attack’ (JCHR, 2016: 7).

The use of drones for targeted killing in counter-terrorism, as opposed to counter-insurgency operations, is a relatively new and highly contentious area of international law and politics. It is well known that the United States has been using drones extensively to combat terrorism and – at least under President Barrack Obama – published guidance on its policy for doing so (White House, 2016), but the United Kingdom has so far denied that it has a targeted killing policy. The 2015 strike is therefore noteworthy as the United Kingdom seems to have changed its counter-terrorism approach to follow more closely the path of the United States. Even though legal justifications were closely aligned with those advanced by the United States, the strike and justifications for it raised a lot of questions with regard to the interpretation of its context and relevant laws. The United Kingdom was not at war with Syria as a state at the time, and the violation of Syria’s sovereignty was based on claims of self-defence to avert an imminent threat. The main focus of this article is not on assessing whether or not the United Kingdom was complying with international law – such discussions have occurred in legal circles (e.g. Blum and Heymann Reference Blum and Heymann2010; Gunneflo Reference Gunneflo2016; Melzer Reference Melzer2008) – but rather on analysing the processes of norm contestation and legal justifications in this context. It focuses on the discursive practices being used to advance particular explanations for actions taken by the government. Understanding law as a discursive process is built on a critical understanding of international law that has not received a lot of attention in international relations circles. Questions of legality are, of course, important in this context, but drones and their use for targeted killing currently exist outside a clear legal framework (i.e. there is no applicable, agreed-upon treaty or customary law), which leads to debates over which legal resources are relevant and can be used to legitimate political actions. To assess connections between law and politics in this context, this article thus analyses government speeches and statements as well as parliamentary inquiries into the incident to look at the ways the UK government contested established meanings of existing norms and utilised international law as a resource to justify its conduct.

In the context of the article, normsFootnote 1 are seen as standards of appropriate behaviour and emerge from state practice, communication and interactions between actors that generate shared understanding (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998). These intersubjective understandings become guidance for the content of the norm and what is deemed to constitute ‘appropriate’ behaviour. Norms are permissive as well as constraining: they can encourage acts of violence (such as targeted killing) as much as they can limit them. Rules govern behaviour as a set of changeable guidelines; at the same time, they are used as discursive resource by states to justify their conduct (Hurd Reference Hurd2017b: 310). In the present case, by engaging with relevant laws and norms, the United Kingdom justified its conduct to make its own actions appear more legitimate in the eyes of the international community. In the process of doing this, the UK Government challenged particular concepts, arguing that this had to be done in order to adjust to a changed environment of new terrorist threats as well as technological advances to respond to them. In this way, technological changes – such as the advancement and availability of drones that can be used for targeted killing operations – have political impact: new technologies and new threats emanating from transnational terrorism create and define norms (see also Bode and Huelss, Reference Bode and Huelss2018; Schmidt and Trenta, Reference Schmidt and Trenta2018) Of particular importance are the ways the norm of self-defence, as enshrined in Article 51 of the UN Charter and customary international law, and its contested component of ‘imminence’ in justifying anticipatory action, are interpreted and implemented.

The main literature that deals with drones and targeted killing (e.g. Bergen and Rothenberg Reference Bergen and Rothenberg2014; Blum and Heymann Reference Blum and Heymann2010; Melzer Reference Melzer2008; Radsan and Murphy Reference Radsan and Murphy2012) focuses on questions of violations of the existing framework, which does not allow to grasp issues related to the law-making character of new technologies and new modes of warfare: that those who use drones for targeted killing have in mind the transformation of laws without necessarily violating them. In this way, new technologies become productive sites of political contestation. Understanding law as a discursive process moves away from assessing legal compliance – that is, whether laws are upheld or not – but makes it possible to uncover and examine ambiguities in legal practice (McBride Reference McBride2017: 321).

The following sections analyse the United Kingdom’s justifications for its targeted killing operation and discuss what effects those justifications have on normative developments. Norms and behaviours need to be studied together because novel standards of appropriate action emerge through practice. As Hurd (Reference Hurd2017b: 310) argues, ‘the dynamism that makes targeted killing so interesting today comes from the fact that the rules and norms around weapons and war are deeply implicated in the very practices and actors which they are designed to regulate’. The contribution of this article to academic debates is therefore twofold. First, it contributes to the literature on targeted killing by focusing on the United Kingdom’s practice and its implications for law and norm development, thereby making an important empirical contribution to the otherwise predominantly US-focused literature on the law and politics of targeted killing. Second, it adds to the constructivist literature by examining norm contestation and resulting normativity – in other words, how states interpret and enact different bodies of law and meanings of relevant norms in a given context. Debates in International Relations tend to focus on questions of states’ compliance with international law, and whether states follow or break rules. This article adds to this by examining legal justifications related to new technologies and resulting novel practices. It connects drone debates with larger questions surrounding the impact of new technologies on jus ad bellum — the law governing the use of forceFootnote 2 – and highlights the permissive and constraining power of international law, demonstrating the political power of legalisation.

The article starts by outlining the context of the UK drone strike before discussing the importance and relevance of norm contestation as well as international law as process. The subsequent sections then focus on some of the main controversies emerging from the particular targeted killing operation and especially the use of force in self-defence in accordance with Article 51, as well as the meaning and interpretation of what constitutes an ‘imminent’ threat. As argued below, the meaning of ‘imminence’ has been discussed for decades, with the Caroline incident from 1837 still cited as the relevant customary law rule. The concept has been broadened by various actors in recent years, however, so it is no longer seen as a purely temporal concept but as one that includes considerations of causality and necessity by determining the ‘last window of opportunity to act’ to avert the threat. The fact that the United Kingdom advanced such arguments in this instance does not just point to novelty of action but also a decision to justify actions in terms of a revised interpretation and contestation of the existing legal doctrine.

II. The UK policy on drones and targeted killing in counterterrorism

On 21 August 2015, the United Kingdom targeted and killed two UK nationals in Raqqa, in the territory of Syria, with a remotely controlled drone. At the time, the United Kingdom was not involved in the country militarily, and the drone strike that killed Reyaad Kahn (the primary target of the attack) and Ruhul Amin was classed by the UK government as an act of self-defence in line with Article 51 of the UN Charter in a counter-terrorism operation. Reyaad Khan and Ruhul Amin were targeted because they were suspected members of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and their killing was justified by then-Prime Minister David Cameron as an act of self-defence against an imminent threat. Article 51 establishes the right to self-defence in an interstate context, but it does not specify that this right is limited to attacks perpetrated by states or whether they also include actions by non-state actors. In her advisory opinion to the Wall Opinion, Judge Higgins pointed out that ‘there is, with respect, nothing in the text of Article 51 that … stipulates that self-defence is available only when an armed attack is made by a State’ (Higgins, Reference Higgins2004: para 33; see also Buergenthal Reference Buergenthal2004: para. 6; Kooijmans, Reference Kooijmans2004: para. 35). There is much academic support for the notion that Article 51 also allows acts in self-defence against ‘armed attacks’ perpetrated by non-state actors (Wilmshurst Reference Wilmshurst2006: 969–71). Furthermore, there is ample evidence to suggest that states have accepted that international terrorism can constitute an armed attack, thereby justifying self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter.Footnote 3 What ‘imminence’ means in this context of anticipatory action to avert a threat that has not yet materialised, however, is far less clear. Cameron (Reference Cameron2015) argued that targeting Khan by airstrike was ‘the only feasible means of effectively disrupting the attacks planned and directed by this individual. So it was necessary and proportionate for the individual self-defence of the UK.’

The use of force as part of broader military involvement of interstate action in Syria had been subject to debate in the UK Parliament on a number of occasions prior to the strike. On 29 August 2013, MPs did not support UK involvement in Syrian airstrikes as part of a US–UK coalition.Footnote 4 At the time, opposition leaders were concerned that acting unilaterally would breach international law, and doing so would set a precedent of invading a country without UN Security Council authorisation (House of Commons Debate, 2013: Column 1454). Similarly, in September 2014, the House of Commons explicitly rejected a request by the government to extend its military action against ISIL in IraqFootnote 5 to include airstrikes in Syria. As a result, the UK Parliament expressly excluded Syria from its ongoing military engagement in Iraq and resolved that any airstrikes in Syria needed to pass a separate vote (House of Commons Debate, 2014). At the time, concerns were based mainly on fears of repeating mistakes made in the 2003 Iraq War including a lack of transparent legal advice, with no concrete timetable for action and no UN sanctions (Mason, Reference Mason2013). The government kept the option of extending its mission into Syria open, however, by stating that if ‘critical interests’ were at stake, Cameron could act immediately and explain to the House of Commons afterwards (House of Commons Debate, 2014).

He did so on 7 September 2015. Cameron announced the drone strike in the House of Commons, claiming that it had been an act of self-defence to protect the United Kingdom from imminent attacks being plotted by Khan. Cameron also stated that this was a ‘new departure’ as it was the first time the United Kingdom had conducted a lethal drone strike against a terrorist target in a state with which the United Kingdom was not in an armed conflict. Conflicting explanations as to what that ‘new departure’ entailed led to some confusion, which will be discussed further below. Given the gravity and importance of the strike that occurred outside of an already established military operation, two Parliamentary Committees launched inquiries into the UK action. On 29 October, the Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR) announced an inquiry into the ‘UK Government’s Policy on the Use of Drones for Targeted Killing’ to understand the policy and legal basis for the UK government’s decision. The Committee stated:

We decided to hold an inquiry into the matter in view of the extraordinary seriousness of the taking of life in order to protect the lives of others, which raises important human rights issues; the fact that the Government announced it as a ‘new departure’ in its policy; and because of the importance we attach, as Parliament’s human rights committee, to the rule of law. (JCHR 2016: 5)

The Committee clarified that it was not going to focus on the use of drones in particular instances, but that it was interested in the government’s overall policy with regard to the use of drones for targeted killing. The Committee acknowledged that the changing nature of armed conflict and technological advances have transformed warfare, necessitating ‘an urgent need for greater international consensus precisely on how the relevant international legal frameworks are interpreted and applied in this new situation’ (JCHR 2016: 6). On the same day, the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament (ISC) announced that it would investigate the intelligence basis for the strike, encompassing ‘the assessment of the threat posed by Reyaad Khan, the intelligence that underpinned that assessment, and how that intelligence was used in the ministerial decision-making process’ (ISC 2017: 1). The Prime Minister agreed to the latter investigation only with a narrowed scope, which he justified on grounds of national security concerns.

III. International law and legal justifications

The United Kingdom has long held the very general idea of the ‘rule of law’ in interstate relations as a central concern and was therefore eager to justify its actions as being in line with its existing legal obligations. For instance, the 2015 National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review (HM Government 2015) underlines the United Kingdom’s respect for law in general terms.Footnote 6 In the specific context of the right to use force in self-defence, then-Attorney General Jeremy Wright (Reference Wright2017: 4) argued that ‘international law sets the framework for any action taken by Sovereign States overseas, and the UK acts in accordance with it’. Similarly, the JCHR (2016: 5–6) maintained that ‘it is obviously right in principle that the Government is subject to the rule of law and must comply not only with domestic law but with the international obligations it has voluntarily assumed’. There is also a recognition that the United Kingdom can exert leadership and influence over other countries, and that its action ‘sends an important signal to the rest of the world’ (JCHR (2016: 5–6) Similarly, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Drones (APPG)Footnote 7 concluded that ‘if the UK is to influence others to encourage compliance with international law, it is imperative that it leads by example’ (APPG 2018: 44). These different statements clearly demonstrate that the United Kingdom recognises the importance of its legal obligations and also that it is conscious of the potential for setting precedents that others might follow.

Law and politics, and the importance of legitimating action

Debates persist regarding which rules apply to new technologies (such as drones), as well as new modes of warfare (such as terrorism), and how those rules need to be interpreted. This opens up a space for discursive practices that result not necessarily in a weakening of those laws and norms, but in a renewed argumentation of how they can be interpreted in the altered context. Actions are justified with reference to international law, but this is not the same as compliance, because ‘what it means to comply, to act consistently with one’s obligations, is the currency of contestation in the politics of international law’ (Hurd Reference Hurd2017a: 8). International law incorporates written treaty law as well as unwritten expectations about appropriate behaviour, such as customary law or norms. Norms influence what actors deem to constitute moral conduct – that is, acting appropriately in the given context as well as engaging in legally accepted behaviour; they are thereby standards of appropriate behaviour. Norms emerge from practice, communication as well as interaction between actors and they generate shared understandings. The interpretation of norms requires establishing a relationship between formal validity which means, for instance, documented language in a treaty, and its social recognition, its appropriateness in a given context, achieved through social interaction (Wiener and Puetter Reference Wiener and Puetter2009: 10–11). Laws often overlap with norms, they define behaviour that is legal or illegal, set out potential exceptions and also what kinds of punishments for breaking laws exist.

International law is not static but a continuing process and as such it is necessarily flexible to adapt to and be able to address changes, such as new technologies that enable different forms of warfare (e.g. see Brunnée and Toope, Reference Brunnée and Toope2010; Higgins, Reference Higgins1968). Law consists of practices of legality as well as normative contestation; it embodies shared understandings between different actors that use legal provisions to justify their actions. To understand change in international law, the dual quality of norms needs to be considered: they are ‘both structuring and socially constructed through interaction in a context’ (Wiener Reference Wiener2008: 27). Norms influence state practice, and changing norms can lead to changes in state behaviour, which in turn influences international law. Because state behaviour is influenced by norms, acts that might violate existing rules can – with sufficient support from other states – lead to a reformulation of those rules. Even though legal rules may be vulnerable to contestation, they are ‘underwritten by shared understandings’ (Sanders Reference Sanders2018: 12). Understanding how norms evolve and change is therefore crucial to understanding developments in international law. (see also Glennon Reference Glennon2005: 957). This connects to debates in international legal scholarship that argue law itself allows for processes of change and evolution through practice – that is, claims and counter-claims about what constitutes state practice in relation to customary law or treaty interpretation. As international law is created mainly by states (in the absence of an equivalent to a central body that is entitled to modify or create rules in domestic law) practice leads to changes in international law. ‘International lawyers advance, debate, apply, and modify rules to deal with every aspect of international relations.’ This supports ‘the idea of international law … as a political tool’ (Scott Reference Scott1994: 321)

The UK Government argued within the boundaries of international law and referred to other states’ actions as precedents, but only had limited success in convincing the Houses of Parliament that the targeted killing operation was indeed lawful. The government’s pronouncements regarding the legality of its actions were met with criticisms and scepticism from a range of MPs, followed by calls for more scrutiny and transparency in the form of formal committee inquiries. Such conflicts and arguments over interpretations are important because they lead to an engagement with norms through contestation (Wiener Reference Wiener2018: 10). Norm contestation is ‘both a social practice of merely objecting to norms (principles, rules, or values) by rejecting them or by refusing to implement them, and … a mode of critique through critical engagement in a discourse about them’ (Wiener Reference Wiener2017: 1).

In this way, law becomes a discursive process that embodies shared understandings and states’ interests. Governments interpret legal provisions in a manner that justifies their actions, but at the same time they are constrained by the boundaries of law. In other words, in order to a make legal case, states are limited in their choices and the ways they can justify those choices. Law provides a frame of reference; it ‘serves a communicative function: to express one’s claims in legal terms means to signal which norms one considers relevant and to indicate the procedures one intends to follow and would like others to follow’ (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2011: 23).

Examining the United Kingdom’s use of drones for targeted killing demonstrates interactions between technologies, behaviour and norms, with the aim of analysing ‘the productive power of international rules and norms’ (Hurd Reference Hurd2017b: 311) New technological advances impact the threats faced by the United Kingdom, as well as the ways in which it can respond to them. As outlined above, warfare has changed over the years, away from purely state-centred uses of traditional weapons against clearly identifiable enemies and territories. (e.g. see Strachan and Scheipers Reference Strachan and Scheipers2011). At the same time, new technologies to confront those threats are being developed, which necessitate a reassessment of legal provisions and how they can be regulated. This is essential because ‘every legal system needs to be able to develop its rules to take into account the evolution and changing exigencies of the society it regulates’ (Duffy Reference Duffy2015: 17). The JCHR (2016: 6) therefore argued for ‘an urgent need for greater international consensus about precisely how the relevant international legal frameworks are interpreted and applied in this new situation’. This is an important task, as Rosa Brooks (Reference Brooks2014: 98) asserts in the context of the United States’ use of drones: even though drone strikes challenge the international rule of law, ‘they also represent an effort to respond to gaps and failures in the international system’.

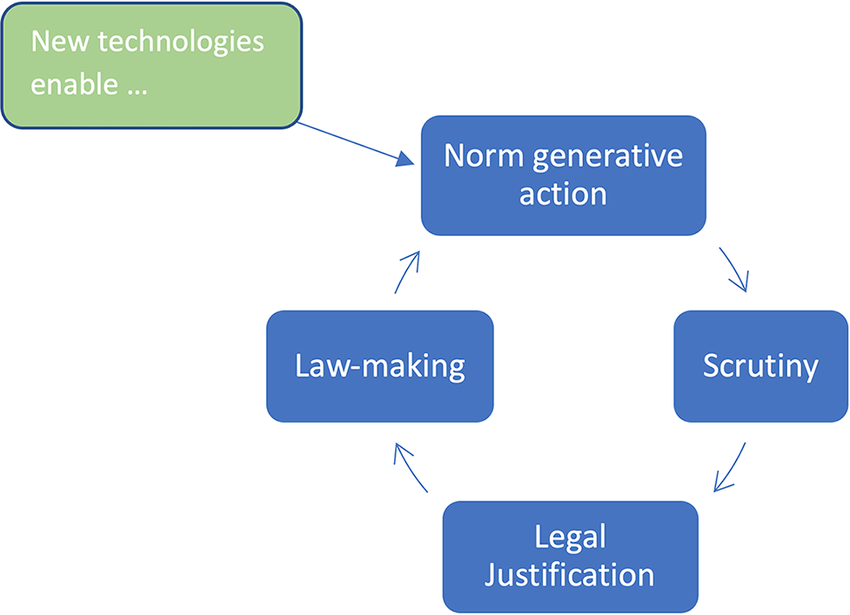

States challenge, contest and disagree over meanings of law in response to technological developments. This leads to changes in the interpretation of existing rules and norms, and the way their meanings are enacted to arrive at behaviour that can be deemed appropriate in a given context. By assessing such strategic use of international norms and laws to pursue certain objectives, it is possible to examine how new technologies, such as drones, can create, shape and define norms and laws (see also Bode and Huelss Reference Bode and Huelss2018). In this sense, a cycle emerges in which the combination of new technologies and legal justification has potential law-making effects: new technologies enable norm-generative actions, such as (in the present case) targeted killings in counter-terrorism. This then triggers increased scrutiny that leads to legal justification, which has the potential for law-making, which then in turn legitimises targeted killing operations.(See figure 1)

Figure 1. Contribution of new technologies to law and norm development

States aim to justify their conduct within the reference frame of international law in order for their actions to be perceived as legitimate. Such legal justification is always a political act; states use legal language as a resource to further their own ends, but this ‘does not mean law is unimportant. Precisely the opposite. State practice invests in law’s discursive authority’ (Hurd Reference Hurd2014: 51). In this way, states aim to transform law in order to better fit their policy choices into the changed environment in which they are acting. Conceiving of law in such a way is in line with the United Kingdom’s approach to its legal justification. As Wright states:

International law is not static and is capable of adapting to modern developments and new realities. In my view, this capacity to adapt is both positive and necessary. It ensures that we are able to lawfully and effectively respond to changing scenarios and needs in a principled way, applying the law in a way that recognises the world we live in now. Being unable to do so could weaken the rules-based international order … This places states in a unique position, in which the law is shaped, in significant part, by what those states do, and a clear understanding of why they do it. That is why speeches like this one need to be made. Not to complain that international law cannot keep pace with the danger the world faces today, but to argue that it can, that it does, and that it has. (Wright Reference Wright2017)

IV. A ‘new departure’

As Parliament had rejected sanctions on airstrikes against Syria in the earlier House of Commons vote, the government needed to frame the drone strike against Reyaad Khan in a way that clearly distinguished it from other military operations in which the United Kingdom was already involved in in the region as a counter-terrorism measure. As Cameron argued:

I want to be clear that this strike was not part of coalition military action against ISIL in Syria – it was a targeted strike to deal with a clear, credible and specific terrorist threats to our country at home. The position with regard to the wider conflict with ISIL in Syria has not changed. (Cameron Reference Cameron2015)

He crucially stated that this action therefore constituted a ‘new departure’ for the United Kingdom:

Is this the first time in modern times that a British asset has been used to conduct a strike in a country where we are not involved in a war? The answer to that is yes. Of course, Britain has used remotely piloted aircraft in Iraq and Afghanistan, but this is a new departure, and that is why I thought it was important to come to the House and explain why I think it is necessary and justified. (House of Commons 2015)

Cameron referred to the ‘new departure’ in terms of an act of individual self-defence of the United Kingdom in response to a direct threat in line with Article 51 of the UN Charter. Such action is permissible against an imminent threat, taken as a last resort and in a proportional manner.Footnote 8 Cameron said:

We took this action because there was no alternative. In this area, there is no Government we can work with; we have no military on the ground to detain those preparing plots; and there was nothing to suggest that Reyaad Khan would ever leave Syria or desist from his desire to murder us at home, so we had no way of preventing his planned attacks on our country without taking direct action. (Cameron, Reference Cameron2015)

Using this line of reasoning, Cameron appealed to notions of Syria as a government that was unwilling or unableFootnote 9 to deal with the threat itself, that the action was done as last resort and finally, that it was done as part of a new reading of what constitutes an ‘imminent’ threat. Such a widened interpretation of ‘imminence’ includes not just a temporal dimension (‘something is going to happen anytime soon’), but – as will be argued further below – also a causality link of a ‘last window of opportunity’ to act to avert a threat. In this way, Cameron used legal justification to maintain that the strike was in compliance with the applicable international legal frameworks. He also confirmed that the Attorney General had advised on the legal issues surrounding the operations and had concluded that there was a ‘legal basis for action’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron2015).

As the UK Parliament had expressly voted to authorise the use of airstrikes in Iraq but not in Syria, the government placed heavy emphasis on this ‘self-defence’ justification in the context of a terrorist threat. Cameron set out that he would ‘always be prepared to take that action. That is the case whether the threat is emanating from Libya, from Syria or from anywhere else’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron2015). In this sense, the ‘new departure’ can be understood as part of a policy of using drones for targeted killing outside of an armed conflict, and it was therefore perhaps not surprising that concerns were raised that the United Kingdom might be heading the same way as the United States in this regard. As Caroline Lucas MP criticised:

There are serious questions to be answered about the legality of the strikes, as well as the lack of robust oversight. Given the evidence from the USA, where former heads of defence and others have called their secret use of drones a ‘failed strategy’, it’s crucial that the UK’s actions to date and moving forward are subject to proper debate and scrutiny, particularly as its apparent new ‘Kill Policy’ goes beyond even what the US has been doing. (Lucas, Reference Lucas2015)

If the United Kingdom were not engaged in a war or armed conflict with Syria at the time of the strike (as Cameron had argued), an isolated military strike in self-defence would not reach the threshold of a non-international armed conflictFootnote 10 and would therefore fall within International Human Rights Law, which prohibits lethal targeting outside of war (except in very narrow cases of self-defence). Furthermore, in that case the United Kingdom would be bound by the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which has a higher threshold for permitting lethal force in self-defence than the Laws of War. In its report, the ISC agreed that even though there was no doubt that Khan posed a serious threat to the United Kingdom, whether this amounted to an ‘armed attack’ was a subjective assessment which the ISC was unable to reconstruct due to the lack of government transparency (ISC 2017).

Even though the JCHR was very critical of the government’s reluctance to provide a clear answer to the question of which body of law applied to targeted killing operations (JCHR 2016: 9), it accepted the government’s assertions that this particular incident was part of the armed conflict in which the United Kingdom was already involved in Iraq. This view is supported by others, who argue that

from an international law standpoint, the UK is already in a non-international armed conflict with ISIL, as part of a collective self-defence action on behalf of the Government of Iraq. To the extent that this conflict spills over into Syrian territory and Syria has effectively lost all control over some parts of its territory governed by ISIL (and Raqqa would meet that test), it seems to me that one does not need any additional ad bellum justification, specific to the UK, to attack ISIL fighters in their Syrian stronghold. (Bhuta, Reference Bhuta2015)

Furthermore, the Council of Europe agreed that fighting conflicts with ISIS could be seen as ‘warfare and not police work, so the use of armed drones would be assessed under international humanitarian law.” (Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly 2015). During his evidence session with the Committee, Michael Fallon (Justice Committee 2015) argued that accepting that the conflict with ISIL had spilled over Iraq’s borders did not mean the United Kingdom had adopted the United States’ broad understanding of a global war on terrorist organisations (US Department of Justice 2011); rather, the conflict was confined only to Iraq and Syria.

According to this explanation, the action did not constitute a targeted killing outside of an armed conflict, and was therefore no ‘new departure’. Cameron’s explanations of a ‘new departure’ and resulting questions surrounding applicable bodies of law led to even more confusion and criticism when the UK Mission to the UN reported in a letter dated 7 September 2015 to the UN Security Council that the action was taken partly as collective self-defence on behalf of Iraq. Unlike Cameron’s explanation to the Houses of Parliament, which was based solely on the United Kingdom’s inherent right to individual self-defence, the letter that was officially sent to the United Nations set out that the United Kingdom had

undertaken military action in Syria against the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in exercise of the inherent right of individual and collective self-defence … This air strike was a necessary and proportionate exercise of the individual right of self-defence of the United Kingdom. As reported in our letter of 25 November 2014, ISIL is engaged in an ongoing armed attack against Iraq, and therefore action against ISIL in Syria is lawful in the collective self-defence of Iraq. (Rycroft Reference Rycroft2015)

The two statements contradict each other, with the Prime Minister claiming that the strike was not part of coalition action in Iraq and the UN letter stating that it was. As Christine Gray argues,

if the targeted killing was – as the UK implied to the UN Security Council – part of an ongoing armed conflict in Syria, then it would not in fact mark a change of policy by the UK despite the language of the Prime Minister. It would be consistent with UK practice of using drones to kill identified individuals in the ongoing armed conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. (Gray Reference Gray2016: 199)

During the JCHR inquiry evidence session, Jennifer Gibson (a lawyer working for the charity Reprieve) argued that there was a

huge inconsistency between what the Prime Minister said on 7 September and his Cabinet then submitted to the UN. He stood up in Parliament and said quite explicitly that this was not about collective self-defence of Iraq, this was not about ISIS, this was about a direct threat to the UK. Under that invocation of Article 51 in the UN charter, there has to be an imminent threat to the UK. (JCHR 2015)

Confusion surrounding the discussions of what the ‘new departure’ meant had the effect that the government’s legal justification and the way it interpreted relevant norms and laws was being questioned, which led to increasing concerns about the legality of the strike. (Knowles and Watson Reference Knowles and Watson2018: 23)

The different justifications seem to have been given with different audiences in mind (Gray Reference Gray2016: 199). The collective self-defence argument is not overly new or contentious. The UK was, at the time, already engaged in military action as part of coalition forces against ISIL in Iraq, and argued that the drone strike was part of that very same conflict, which had extended into an area in Syria that the government was unable to control. That strike could therefore be seen as an extension of the agreed mandate of collective security.Footnote 11 The individual self-defence argument that Cameron advanced in Parliament is more controversial, but it is best understood in the context of the previous House of Commons vote that had expressly rejected an extension of UK involvement in Iraq to Syria. The justification for the drone strike was made to maintain that the government had not exceeded its given mandate and that it was adhering to its legal obligations. Discussions were framed in legal terms which is important for legal justification and norm contestation that have potential law-making effects. The JCHR Inquiry (JCHR 2016), however, accepted the subsequent government explanation that the ‘new departure’ did not relate to the United Kingdom using force outside of an armed conflict, but that it was about the constitutional convention governing the use of force that the government could act immediately and explain to the House of Commons later. In his evidence to the Committee, Sir David Omand, former UK Security and Intelligence Coordinator, said Cameron’s address to the House of Commons was ‘a political statement to explain to the House that, although this strike was in Syria, it was not going against the will of the House, which had failed to authorize strikes against President Assad’s forces’ (JCHR 2015).

V. Imminence and self-defence

Regardless of whether or not the action was indeed taken in individual or collective self-defence, the drone strike raises a number of issues that show how the United Kingdom is using law as a way to justify its actions. Self-defence has a significant place in international law, as it is the only line of argument that states can pursue to use force unilaterally without Security Council authorisation (Hurd, Reference Hurd2016). In this way, law (in the form of Article 51 and the ban on war) is not only constraining, but also a permissive resource that states can use to justify their conduct. Governments use law to legitimate their actions, to claim they are acting lawfully. ‘The permissive power of international law is of central importance to governments: legality, when it lines up with state interests, enhances state power and governments strive energetically to use it to their own ends’ (Hurd Reference Hurd2016: 14). By using self-defence arguments, the UK government is using international law as a resource to legitimise its targeted killing operation.

Most importantly, discussions surrounding the question of what constitutes an ‘imminent’ threat in this context not only demonstrate the contested nature of international law, but also highlight its legitimising and constraining powers. The debates illustrate the United Kingdom’s strategic use of particular norms and laws as resources to justify its actions. The question of imminence is often discussed with reference to the so-called Caroline incident of 1837, which established a rule of customary state practice regarding preventing self-defence against an imminent threat.Footnote 12 According to this precedent, the need to use force in self-defence needs to be ‘instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation’ (Shaw Reference Shaw2017). This precedent established that there is no requirement to wait until an attack has happened before a state can act in self-defence, but that an imminent threat can be addressed before it materialises. This notion of ‘imminence’ and what it means in the current context of counter-terrorism, as well as the availability of new technologies to respond to it, has become subject to major debates.

Expanded conceptions of imminence and self-defence were first advanced by the United States, particularly during the George Bush administration that developed notions of preventive and pre-emptive actions in response to terrorist threats (see Warren and Bode Reference Warren and Bode2015 for an extensive discussion of the concept and its origins). The concept became part of the 2002 US National Security Strategy (US Government 2002) and numerous speeches and government documents further established the United States’ line of argumentation towards a general right of pre-emption. The United Kingdom has been less open about its approach, with only few mentions of how it conceives of discussions surrounding anticipatory self-defence (see for example successive House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee reports between 2002 and 2006, including its 2002–03 report (Foreign Affairs Committee, 2002–03: at)). In 2004, the Government’s legal framework in relation to self-defence was set out as follows by then Attorney-General, Lord Goldsmith:

it has been the consistent position of successive United Kingdom Governments over many years that the right of self-defence under international law includes the right to use force where an armed attack is imminent … but [this] does not authorise the use of force to mount a pre-emptive strike against a threat that is more remote. However, those rules must be applied in the context of the particular facts of each case. That is important. The concept of what constitutes an ‘imminent’ armed attack will develop to meet new circumstances and new threats. (House of Lords, 2004: Col. 370)

In this way, Goldsmith left the door open for competing interpretations of the concept to adjust to a changing environment in which states act. Self-defence and imminence are seen not as static or given concepts but that they have to adjust to changing circumstances.

In 2012, Sir Daniel Bethlehem, former Legal Adviser to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, set out sixteen principles relevant to the use of force against non-state actors.Footnote 13 These principles include the nature and probability of an attack, its likely scale and the potential injury, loss or damage from it. Particularly noteworthy in this context is Principle 8, which deals with ‘imminence’:

The absence of specific evidence of where an attack will take place or of the precise nature of an attack does not preclude a conclusion that an armed attack is imminent for purposes of the exercise of a right of self-defense, provided that there is a reasonable and objective basis for concluding that an armed attack is imminent. (Bethlehem Reference Bethlehem2012: 775)

Even though this principle demands ‘a reasonable and objective basis’ that an armed attack is likely to happen, what this actually entails is open to interpretation. It is not necessary to provide specific evidence of where an attack will take place or of its precise nature. In this way, law’s imprecision opens the door for contestation and competing legal justification.

Under the Obama Administration, the United States made the case for expanding the notion of imminence by stating that:

Once a State has lawfully resorted to force in self-defense against a particular actor in response to an actual or imminent armed attack by that group, it is not necessary as a matter of international law to reassess whether an armed attack is occurring or imminent prior to every subsequent action taken against that group, provided that hostilities have not ended. (White House 2016: 11)

Here, the assumption is made that al Qaeda and other terrorist organisations are constantly plotting against Americans and that possible terrorist attacks therefore pose a new kind of threat that is difficult to predict. The 2013 Tallinn Manual (Schmitt Reference Schmitt2013–14), written by an international group of experts led by an American, similarly advanced the argument that ‘imminence’ needed to be assessed with regard to the ‘last feasible window of opportunity’ to act to avert the threat and that this could be either just before an attack was taking place or long before. This is a further attempt to move away from the purely temporal definition of imminence. As Schmitt, a proponent of the US position, argues, ‘in an era when a catastrophic armed attack may fall without warning, as with a terrorist attack using a weapon of mass destruction, a strict temporal interpretation no longer makes sense’ (Schmitt Reference Schmitt2013–14: 89).

Following the Khan strike and in response to the JCHR inquiry, the UK government similarly argued for a change away from strict temporal assessments and that imminence should rather be understood as ‘the last window of opportunity to act’ to prevent a threat from materialising. The Government stated that the circumstances of the threat were important and that it ‘must take a view on a broader range of indicators of the likelihood of an attack, whilst also applying the twin requirements of proportionality and necessity’ (JCHR 2016: 16). Jeremy Wright, in his written evidence to the JCHR, said that the:

Caroline case, as you will appreciate, goes back to the 19th century, and we are talking about very different circumstances now. Certainly, what has not changed is that, in order for any state to act in lawful self-defence, it is necessary to demonstrate that there is an imminent threat that needs to be countered and that, in countering that threat, the action taken is both necessary and proportionate, and it is necessary to demonstrate that what you do complies with international and humanitarian law. In all of those respects I was satisfied that this was a lawful action. To that extent, we are clear about what has happened on the basis of principles of self-defence that are well established. (Justice Committee 2015)

Addressing the need to interpret and implement laws in ways that respond to changing circumstances, he further argued that:

One of the things we probably need to think about as a society in any event is what imminence means in the context of a terrorist threat, compared with back in the 1890s when you were probably able to judge imminence by a measure of how many troops you could see on the horizon. That is something that everyone – including the academic world, no doubt – will want to consider, but the basic tenets of acting in self-defence have not changed. (Justice Committee 2015)

As the Bethlehem Principles and their interpretation of ‘imminence’ have been endorsed in similar ways by the United States and Australia,Footnote 14 Wright claimed that the United Kingdom further advancing this legal rule was evidence of

UK leadership in action – working with our international partners to advance the security of our nation and of others, within a legal framework. It is leadership with practical benefits, too – because if we know that others share a common understanding of the legal tests to be met that allows us to work together more effectively. (Wright Reference Wright2017)

Wright maintained that the UK was not developing new legal concepts, but that it was advancing new interpretations of already existing obligations. In this way, the United Kingdom is using international law to justify its conduct and, by claiming ‘leadership in action’, is also trying to change it in the process.

The availability of modern technologies as well as new threats emanating from terrorist organizations might require different legal justification and interpretation of what ‘imminence’ means in the context of counter-terrorism operations, but removing all temporal constraints is a major challenge to the concept of self-defence. It is questionable whether it is indeed justifiable to remain in a constant state of ‘imminence’ without evidence of any particular attacks being planned. Moreover, such an interpretation conflates temporal considerations with principles of necessity and propotionality, which are substantively different concepts in International Humanitarian Law, that the action needs to be necessary to accomplish the goal and that it needs to be proportionate to the kind of threat it addresses. These are two different considerations regarding the question of whether an attack is indeed temporarily imminent, which leads to contested legal justification between proponents and opponents of a broadened understanding of ‘imminence’.

The United Kingdom is using the United States as a precedent, claiming its policies and understanding of ‘imminence’ reflect the ‘modern law in this area’ (Wright Reference Wright2017). Referring to the Bethlehem Principles, he argues that it is ‘informed by detailed official-level discussions between foreign ministry, defence ministry, and military legal advisers from a number of states who have operational experience in these matters’ (Wright Reference Wright2017). However, even though the Principles may be accepted by a number of states, it is only a small group of (largely Western) states that repeatedly refer to each other to claim they are endorsing ‘established practice’ or ‘accepted opinion’, thereby trying to establish opinio juris and new rules of customary international law. Such an approach ignores a large number of other states that object, or at least do not voice agreement.Footnote 15 As Marko Milanovic stated in his evidence to the APPG evidence session:

You have a group of states, state legal advisors, they are meeting over the course of several years. They are talking next to each other. By the way, the states they’re meeting there are all powerful states. You don’t have Iraq at the table or, you know, Zimbabwe. It’s the UK, US, France … and then they meet together and then they formulate some principles that look good to them. (APPG 2017)

In its final report, the APPG (2018: 44) was equally critical of the UK government’s approach, questioning whether the government was ‘seeking to stretch the principles contained in existing legal frameworks abroad, rather than conforming its practice to existing principles’, which it saw as a ‘radical expansion of the rights to self-defence’ to enable pre-emptive strikes. Such stretching of legal concepts to fit its use of force which can lead to ‘the further erosion of international legal norms. However, even though the United Kingdom and the United States are trying to mainstream their understanding of imminence, ‘two states do not a customary rule make, however powerful those states may be. And we cannot simply ignore the states in the Global South, however inconvenient powerful states in the Global North may find their views’ (Heller Reference Heller2015).

A major problem related to the United Kingdom’s approach is the lack of transparency in its decision to target Khan.Footnote 16 The ISC aimed to assess the intelligence basis for the lethal strike and the threat he posed to determine the grounds for individual and collective self-defence in accordance with Article 51. The final report was published on 26 April 2017; the Committee concluded that, ‘while we believe that the threat posed by Khan was very serious, we are unable to assess the process by which Ministers determined that it equated to an “armed attack” by a state’ (ISC 2017: 30). The report is critical that the Committee had not been given access to primary materials and it had little confidence that it had been given the full facts surrounding the strike (ISC 2017: 72). This is, of course, problematic as the question of whether a particular norm was legitimately contested cannot be assessed if not all facts are known. Any changes to the rule of law as a social practice will only be successful in the longer term if actors provide persuasive reasons and justifications for their actions.

VI. Conclusions

The debates surrounding the international legal framework underpinning and justifying the United Kingdom’s use of drones for targeted killing are important for a number of reasons. First, they demonstrate the effects of new technologies on legal justification in the area of targeted killing. New technologies make new ways of state action possible, yet these choices are communicated as if they were already part of existing legal categories. Law is a process that needs to adapt to changes, and in this way drones and targeted killing are legalised, becoming productive sites of argumentation with potential law-making effects. Second, the debates underline the importance of legal justification in times of conflict and change more generally. To justify state conduct, law is being used politically, not only with the aim to change it but also to fill gaps in the law to regulate new technologies and the ways in which they are being used (see also Hurd Reference Hurd2017a: 84). The result is not necessarily a decline in the importance of the existing framework, but it highlights the political utility in using legal resources to justify policy choices. This has important implications for other areas of new technologies and associated threats, such as cybercrime and cyber warfare. In recognition of a need to find agreement in this area, the United Kingdom highlights cyber as an area of priority, which was addressed in its Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy of March 2021 (HM Government, 2021). As part of the Review, the United Kingdom established a National Cyber Taskforce, which is charged with supporting the United Kingdom’s national security priorities with offensive cyber operations. The Taskforce set out that, ‘The UK is committed to using its cyber capabilities in a responsible way and in line with UK and international law’ (GCHQ 2020). It is clear that new and evolving technologies will continue to bring novel challenges and that international law must constantly adjust to be able to regulate them.