The number of elderly people is projected to grow from an estimated 524 million in 2010 to nearly 1·5 billion in 2050, with most of the increase in developing countries(1). The ageing process in elderly people can have many deleterious effects including reduction of physical function, negative emotional responses and decreased social interactions and productivity. These can cause a significant burden on the healthcare system(Reference Kristianingrum, Wiarsih and Nursasi2,Reference Ishak, Yusoff and Rahman3) . Malnutrition is one of the most common health problems linked with physiological and psychological changes caused by the ageing process in elderly people.

Based on European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, malnutrition is a state of nutrition in which a deficiency or excess (or imbalance) of energy, protein and other nutrients causes measurable adverse effects on tissue/body form (body shape, size and composition) and function and clinical outcomes(Reference Lochs, Allison and Meier4). Malnutrition in elderly people is reflected by either involuntary weight loss or low BMI. However, prevalence of malnutrition strongly depends on the setting, on underlying diseases, as well as on screening and assessment methods(Reference Norman, Haß and Pirlich5). According to one systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Cereda et al. in 2016, prevalence data of malnutrition and nutritional risk in elderly people across different healthcare settings showed a wide range of malnutrition from 3 % in the community setting to approximately 30 % in rehabilitation(Reference Cereda, Pedrolli and Klersy6).

Malnutrition in elderly people has been recognised as a challenging health concern associated with not only increased mortality and morbidity but also with physical decline. These have serious implications for activities of daily living and quality of life in general(Reference Norman, Haß and Pirlich5). The consequences of untreated malnutrition problems are costly. Malnutrition can have profound detrimental impacts including increased health complications, extended length of hospital stay, increased antibiotic prescriptions and hospital readmission(Reference Arjuna, Soenen and Hasnawati7).

One of the promising ways to manage complex health problems including malnutrition in elderly people is through the collaboration of health care providers. The WHO in 2010 recognised interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) as an innovative strategy that will play an important role in mitigating the numerous current global health crises. Collaborative practice happens when multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families and communities to deliver the highest quality of care(8). In Indonesia, the Ministry of Health has already implemented several strategies to prevent health problems in elderly people through routine community monthly screenings by primary care providers. This programme is conducted by midwives or nurses who have the responsibility as the persons in charge of the elderly programmes(Reference Risnah, Hadju and Maria9).

In Indonesia, the majority of elderly people in the general population live with their children and family at home(Reference Plöthner, Schmidt and de Jong10). Recent research showed that the patient and family centered care will improve interdependence among patients, families and health care professionals to achieve optimal health outcomes. Involving family members as key partners in IPCP is a recommended strategy to improve health outcomes(Reference Marshall, Lemieux and Dhaliwal11).

Even though researchers have reported some studies related to IPCP in the care of older adults, however, the research using the views of elderly people and their families is limited and unclear. The current study aimed to address the following question: What are the experiences of malnourished elderly people and their family after being involved in the management of malnutrition with IPCP approach compared with usual care in primary care setting?

Methods

Design

This was a qualitative study using the phenomenological approach. Creswell in 2007 stated that qualitative research has several characteristics including natural setting where participants experience the issue or problem to be studied, the researcher acts as the key data collection instrument and the analysis is focused on participants’ perspectives(Reference Creswell12). The phenomenological approach is widely used as a method to explore and describe the lived experiences of individuals. In its application to research, the philosophical underpinnings of Husserl phenomenology involve detailed reporting of participants’ natural attitudes, intentionality and phenomenological reduction(Reference Christensen, Welch and Barr13).

Sampling

Whenever possible we interviewed the elderly people and their family members together. Elderly people and their family in primary care setting were recruited with the purposive sampling technique. The elderly people and their family members lived in the working area of primary health care in Sleman District, Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, Indonesia, that have primary accreditation. The elderly people who met the criteria was chosen from the database of the primary health centres. The allocation of participants was completely independent.

The inclusion criteria of elderly people were aged 60 years or over who live with their family, have been categorised as malnutrition based on the Mini Nutritional Assessment screening conducted by primary care providers and can fluently speak in Indonesian or Javanese. The participants who refused to participate or have more than two diseases or an uncontrolled degenerative disease were excluded from the current study.

The inclusion criteria of the elderly people’s family were family members who have marriage relationship or blood relation with the elderly people, live with the elderly people more than one year and participate in nutritional care in their home based on implementation from either IPCP or usual care. The family member who refused to be a participant was excluded in the current study.

Intervention group

In the current study, the IPCP implementation was given by an IPCP team from primary care providers consisting of a general physician, dentist, nurse, dietitian and pharmacist who did home visitations once for 45 min. They conducted comprehensive assessments including head-to-toe examination, nutritional status, oral health check and prescribed routine medication if any were needed. Then, they performed innovative strategies that gave health education, showed simple methods in how to prepare healthy food and provided encouragement to the patients and family. In the process, the patients and family were empowered to prepare the food by themselves.

Control group

In the control group, the malnourished elderly people and their family received their usual care from the primary health centre. The usual care was the community monthly screening programme named integrated service centre (Posyandu) for the elderly people provided by the primary health centre which was done by a nurse or midwife. Posyandu is a programme implemented by the Indonesian Ministry of Health to monitor the health status of elderly people with community-based programmes. In the Posyandu programme, the elderly people’s weight, height and blood pressure are measured, and they also receive supplementary food and participate in general health education through volunteer cadres delivered to the elderly people.

Data collection

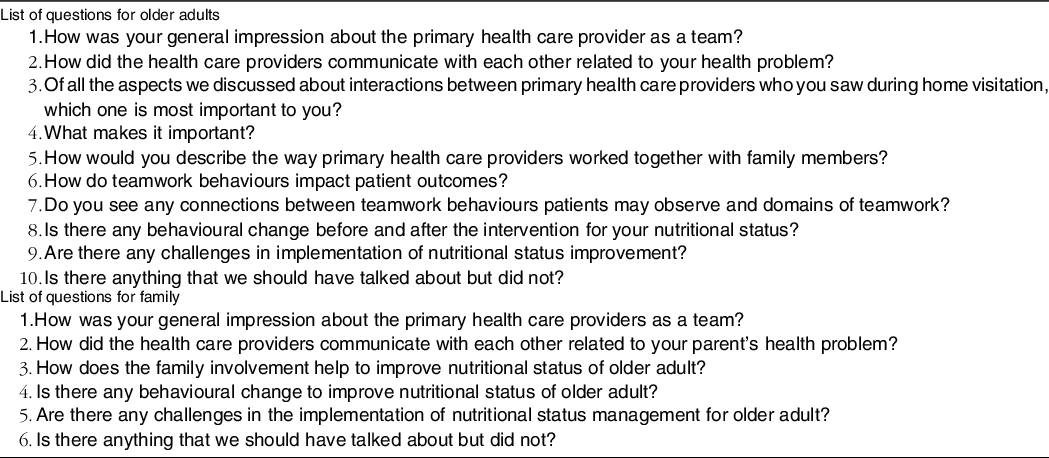

In-depth interviews were held at a place of the participants’ choosing in Sleman District, Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in November 2020. Most of the interviews were conducted in the participants’ home. Questions were open-ended focusing on exploring elderly people and their family’s experiences and perspectives based on a survey developed by Henry et al. (Reference Henry, Mccarthy and Nannicelli14) The list of questions are listed in Table 1. The data collection was conducted until the data reached saturation, which means that no additional data were needed to develop the coded properties of each of the categories(Reference Saunders, Sim and Kingstone15). We decide no further sampling after the data were saturated.

Table 1. List of questions

Patients’ views of teamwork in the emergency department offer insights about team performance (2016).

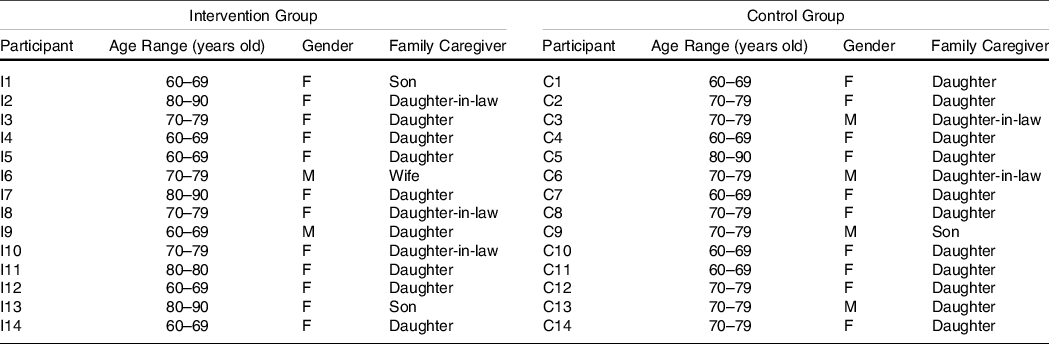

Table 2. Participants’ characteristics

Source: Primary data (2020).

Data analysis

The research team used the phenomenological analysis approach developed and described by Giorgi in 1997, which consists of four steps including to read for a sense of the world, with the clear determination of the essential parts: establishing meaning units, transformation of meaning units into coded categories and determination of structure(Reference Giorgi16).

The leader of the current study is FM who have experience in conducting qualitative study especially in community and family medicine. Two authors (FM and ASL) listened to the recorded interviews separately and made transcripts. We trained the coders who were responsible to arrange codes based on the transcripts of interviews. After discussion concerning the codes, FM, ASL, EPSS and DH reached an agreement about codes that represent the data, and then grouped similar codes together into categories. The categories were examined to develop meaningful themes with quotes from participants to support the main themes and identified categories.

Strategies to enhance quality of study

The trustworthiness of the current study based on the credibility process used triangulation. Triangulation aims to enhance the process of qualitative study using multiple approaches. Investigator triangulation was applied through involving several researchers as research team members and involving them in the process of data analysis. Data were analysed by three different researchers (FM, ASL and HO). The research team held regular meetings during the analysis process. If there were different interpretations, the issue was discussed with other research members (DH, EPSS and HK) until the most suitable interpretation was found.

Ethical issues

The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Padjadjaran with protocol number 914/UN6.KEP/EC/2020. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. To meet the ethical considerations, recruitment of participants was voluntary, anonymity of all participants was maintained and the control group was given the IPCP implementation in the end of the research for equality

Results

The characteristics of the participants

We conducted the in-depth interviews until the data reached saturation. The data were saturated in the interviews with the fourteenth participant of the intervention group and the fourteenth participant of the control group. Fourteen elderly people and their families in the intervention group received the IPCP implementation and fourteen elderly people and their families from the control group provided comparison through their experiences with usual care in primary care. With these two groups, a total of twenty-eight volunteers who are elderly people with malnutrition participated in the current study. The participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

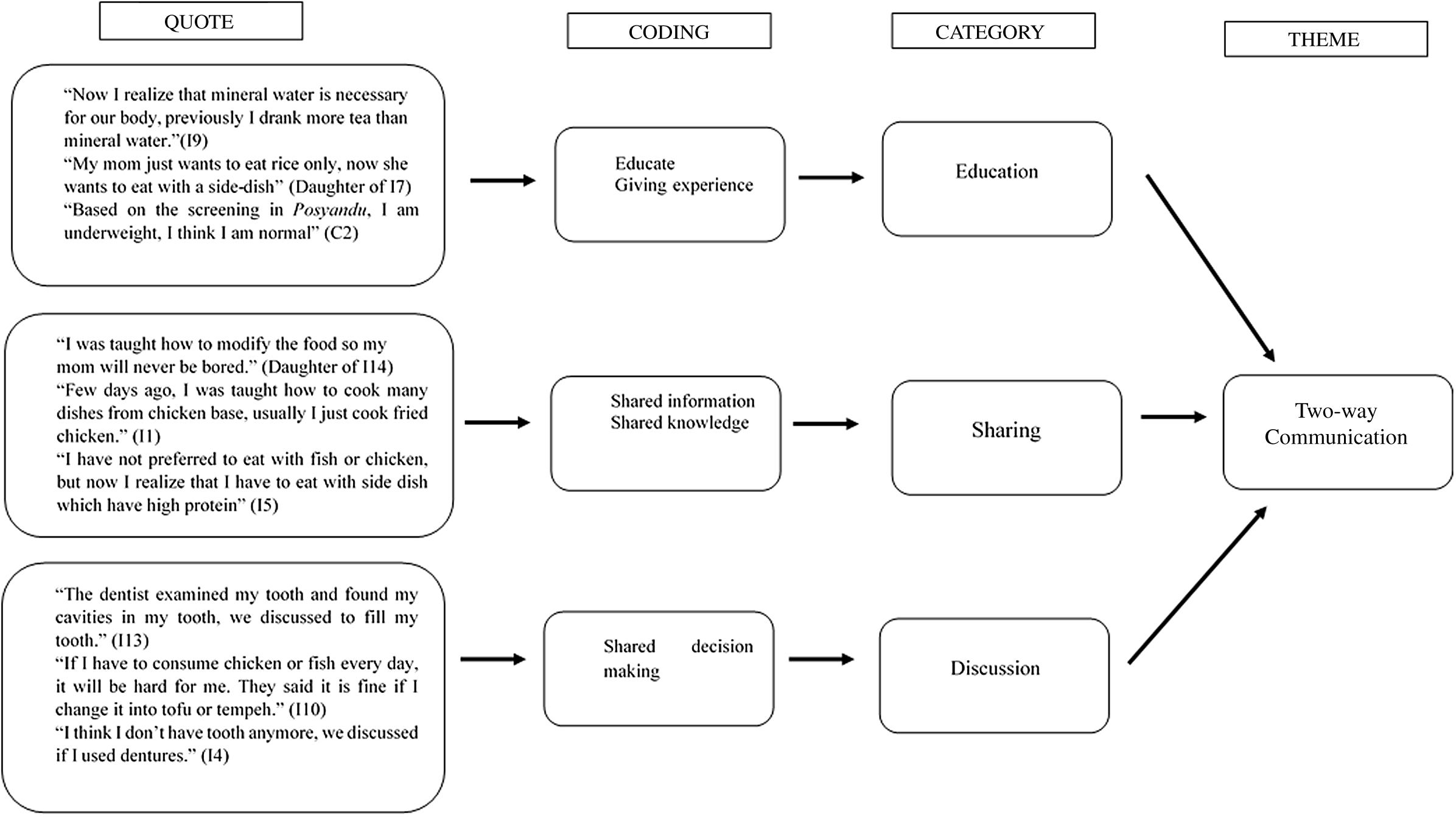

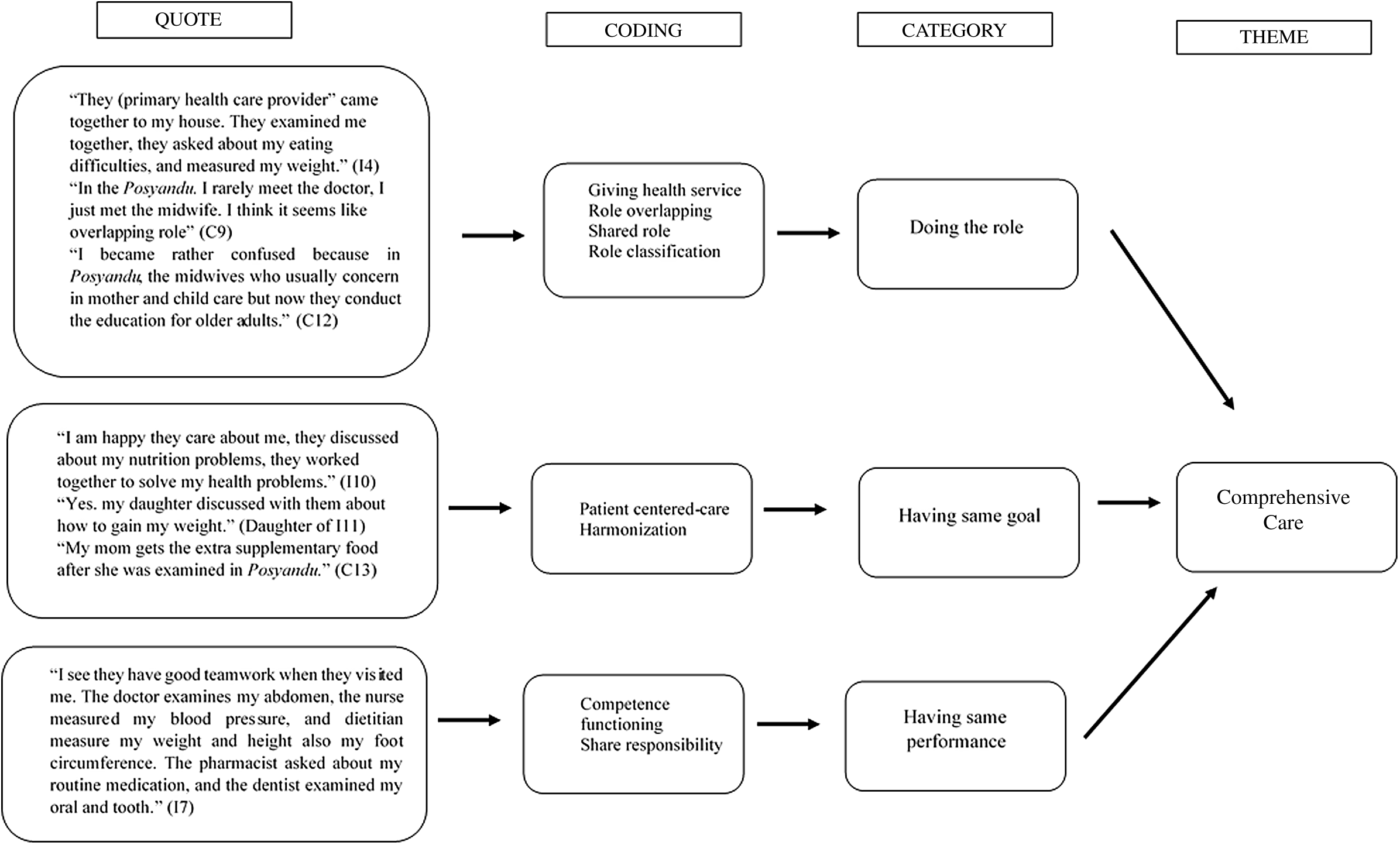

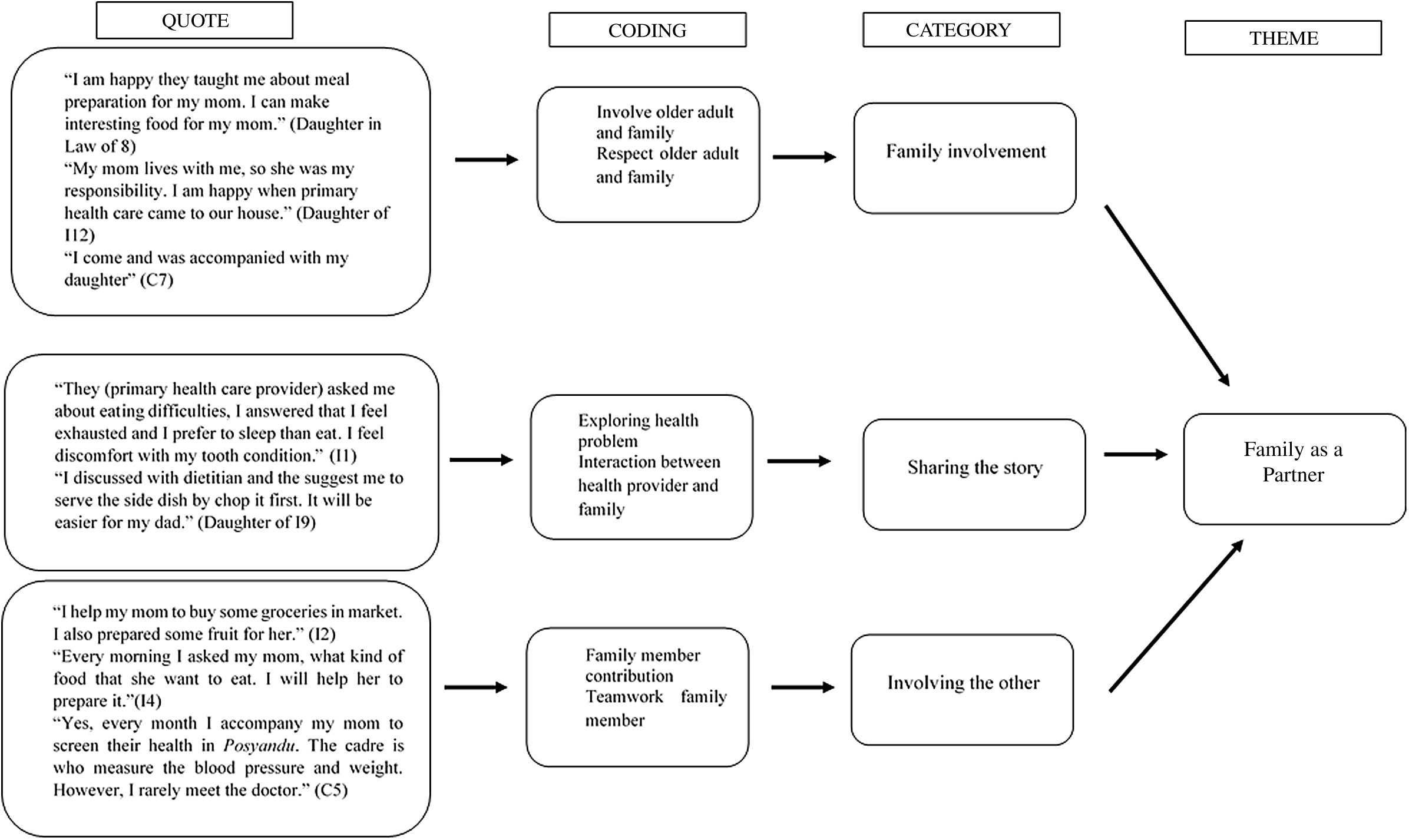

Experiences with the interprofessional team compared with usual care were described from the elderly people and their family’s perspectives. The elderly people and their family talked about their experiences and felt they received more comprehensive care from the interprofessional team and received better health education related to nutrition management. The elderly people and their families from the control group who received the usual standard care experienced overlapping of roles in healthcare and felt unsatisfied from the usual care. These perspectives are further discussed and elaborated in the themes of: (1) Two-way communication, (2) comprehensive care and (3) family as a partner. The process of thematic analysis is described in Fig. 1: Thematic analysis of two-way communication theme, Fig. 2: Thematic analysis of comprehensive care themes and Fig. 3: Thematic analysis of family as a partner theme.

Fig. 1. Thematic analysis of two-way communication theme.

Fig. 2. Thematic analysis of comprehensive care themes.

Fig. 3. Thematic analysis of family as a partner theme.

Two-way communication

The communication between elderly people and their family with health care professionals is essential. Elderly people and their families identified that effective communication of health care providers was necessary in ensuring the elderly people needed nutritional supplementation and involving them in their health care considerations. The IPCP team discussed their problems together and involved the elderly people and family in describing what would meet their needs to improve their nutritional status. The IPCP team gave additional health education and involved the family members to conduct nutritional care for the elderly people.

The elderly people and their family in the control group who received the usual care felt that there was communication from the health care providers, but it was not always clear. Even though the elderly people and their family got information related to ageing and health through the health education in Posyandu; however, they felt it was not enough. Afterwards, they were still confused about nutritional management in their home.

Comprehensive care

Malnutrition is one of the complex health problems that has multi-factorial causes. The elderly people and their families in the intervention group felt that they received more comprehensive care from the IPCP team compared with usual care. The IPCP team members consist of a physician, dentist, nurse, dietitian and pharmacist. They share roles and responsibilities with a primary focus on the patient and their family to address the issue of malnutrition more comprehensively.

In the control group, the respondents felt there was some teamwork in the usual care; however, they felt it was not comprehensive enough to improve their nutritional status. The elderly people felt that there were some overlapping roles in usual care for malnutrition management. The health care providers who have the responsibility to provide malnutrition consultation and management in Posyandu are a midwife or a nurse. Meanwhile, the main responsibility of the midwife is the perinatal concerns in maternal and child health.

Family as a partner

The collaboration of family and health professionals is important to support patient-family-centered care. Family members provide an integral support for the elderly people. Both the intervention and control groups indicated that the family members have some participation in the care of the malnourished elderly people. In the interviews, they shared that they feel happy being involved in the nutritional management for the elderly people with malnutrition.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study providing evidence about the experiences of elderly people and their families while engaging with an interprofessional team for malnutrition management. The findings of the current study show the depth of knowledge related to how the elderly people and their families perceived the three main areas of expressed concerns: the two-way communication, comprehensive care and family as a partner.

In the intervention group who received IPCP implementation, the elderly people have experiences related to the two-way communication from their sharing with the IPCP team. Clear, direct, closed-looped communication is crucial to provide safe patient-centered care. To reach this goal, health care providers in IPCP can express their professional knowledge equally to provide respectful and non-judgemental communication with patients(Reference Stadick17).

Elderly people and their families also have experiences related to more comprehensive care in the intervention group. The current study’s findings are supported by Tsakitzidis et al. in 2017 that found elderly people who receive a comprehensive care intervention perceived significantly higher quality of care(Reference Tsakitzidis, Timmermans and Callewaert18). More comprehensive care can be provided through health professionals from multiple professions working together as a team(Reference Harris, Advocat and Crabtree19).

The importance of family as a partner in elderly people’s nutritional management was supported by Wolff et al. in 2017 who found that elderly people are more vulnerable to malnutrition and other health issues and typically chose to involve family when communicating with health professionals and managing their care. Family members can give beneficial roles by facilitating information exchange and making informed medical decisions. In the IPCP research, home visitations from health providers were found to be significantly more patient centered than treatment visits(Reference Wolff, Guan and Boyd20).

In the control group, the Posyandu programme was not enough to improve the nutritional status for elderly people with malnutrition. These results are supported by a qualitative study conducted by Risna et al. in 2018 that showed IPCP practices were not observed based on their observations of the activities and conditions in Posyandu. Without any team approach, only specific professions had the opportunity to carry out their activities during Posyandu. The Posyandu meetings were usually held in a house of some local people that may limit counseling activities or health promotion. This gap in teamwork indicates that the involvement of all health professions is needed(Reference Risnah, Hadju and Maria9).

The results can provide some suggestions for health policy in primary care settings. One of the strengths of the current study was including the experiences of malnourished elderly people and their family from two points of view, including an intervention group with IPCP experiences and a control group who received their usual care in a primary care setting. While limited by the availability of only a small sample population, the number of participants was appropriate enough for a qualitative study. Further study that involves a variety of cultures could significantly add to our understanding about the experiences of IPCP for elderly people who are malnourished and their families.

Conclusions

The current study explored the elderly people’ and their families’ experiences and revealed that the intervention from the IPCP team involved two-way communication and comprehensive care for malnutrition management. In the control group, there were overlapping roles and not comprehensive enough care based on the usual care in malnutrition management. Both groups shared the experience that family involvement in elderly people care is a positive experience as a partnership in health.

Acknowledgements

We declare that we do not have any sponsor or funding for the current study.

F. M.: lead the research, formulated the research questions, designed the study, data collection, listened to the recorded interviews separately with A. S. L., made transcripts, interpreting the findings and writing the article. A. S. L.: assisted to formulate the research questions, assisted to design the study, data collection, listened to the recorded interviews separately with FM, made transcripts, interpreted the findings, wrote the article and administration of research. H. O.: conducted codes that represent the data, grouped similar codes together into categories, substantially contributed to the research conception and approved the final manuscript. E. P. S. S.: supervisor of research, conducted codes that represent the data, grouped similar codes together into categories, substantially contributed to the research conception and approved the final manuscript. H. K.: supervisor of research, conducted codes that represent the data, grouped similar codes together into categories, substantially contributed to the research conception and approved the final manuscript. D. H.: head of supervisor of research, conducted codes that represent the data, grouped similar codes together into categories, substantially contributed to the research conception and approved the final manuscript.

The current study was approved by the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee with protocol number 914/UN6.KEP/EC/2020. To meet the ethical considerations, recruitment of participants was voluntary, and anonymity of all participants was maintained.

We declare there are no potential conflicts of interest of this article.