Religious affiliation and participation are thought to work as mobilizing structures through which religious participants accrue both organizational and psychological resources, which augment political participation. Specifically, political resource theory asserts that religious participation cultivates civic skills including experience with public speaking, organizational skills, and persuasive abilities, which translate into secular political activity (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Lehman Schlozman1995). Resource theory, however, operates under a heteronormative assumption of religious and sexual identity congruence. That is, many religious traditions condemn sexual and gender identities that challenge heterosexist norms, possibly depriving LGBT religious adherents of the organizational and cognitive resources necessary for translating religiosity into secular political participation (Wood and Bartkowski Reference Wood and Bartkowski2004).

While a number of qualitative studies demonstrate that LGBT people are able to integrate their sexual and religious identities, few quantitative analyses exist that examine the effects of religious identity on sexual minority politics (Meier and Johnson Reference Meier and Johnson1990; Dejowski Reference Dejowski1992; Rodriguez and Ouellette Reference Rodriguez and Ouellette2000; Minwalla et al. Reference Minwalla, Rosser, Feldman and Varga2005; Schnoor Reference Schnoor2006; McQueeney Reference McQueeney2009; Rahman Reference Rahman2010). Do religious LGBT people actually accrue fewer positive psychological resources than non-religious LGBT people? If so, what are the implications for political participation?

The identity-threat model of stigmatization suggests that religious LGBT people may attempt to mitigate identity conflict through avoidance or identity suppression (Sevelius Reference Sevelius2013). In terms of political participation, identity conflict may induce religious LGBT people to avoid political activism, which highlights their conflicting identities. Indeed, the extant literature supports this assertion, in that, LGBT people who, for whatever reason, “hid(e) their sexual identities” appear “less inclined” to engage in political activism, while “the absence of strong religious ties” may be associated with an “increase (in) LGB activism” (Swank and Fahs Reference Swank, Fahs, Dessel and Bolen2014, 63, 65).

Informed by resource mobilization theory, the identity-threat model of stigmatization, and an intersectional approach, I conduct secondary analyses of two survey data sets of LGBT people, one a probability sample and the other a convenience sample of predominantly LGBT People of Color. The results suggest that religiosity is associated with an increased political participation among LGBT people; however, religious LGBT people exhibit weaker psychological association with the LGBT community and are “out” to fewer people. Furthermore, political participation is less likely among those who experience conflict between their religion and sexuality.

RELIGION AND QUEER POLITICAL PARTICIPATION

Political resource and social capital theorists view religion as a resource that provides skills for civic engagement that can be translated into secular political action (Harris Reference Harris1994; Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Lehman Schlozman1995; Calhoun-Brown Reference Calhoun-Brown1996; Putnam Reference Putnam2000; Smith and Walker Reference Smith and Walker2012). However, in much the same way economic resources are not distributed equally throughout society, religiosity does not uniformly motivate political participation, nor do the secular benefits of religiosity accrue to everyone equally. Specific denominational characteristics, ethnic religious traditions, and religiously influenced issue positions exhibit differential effects on political participation (Harris Reference Harris1994; Calhoun-Brown Reference Calhoun-Brown1996; Layman Reference Layman1997; Green Reference Green, Lillian and Beverly1995; Schwadel Reference Schwadel2005; Brown Reference Brown2006; Jones and Cox Reference Jones, Cox, David and Clyde2012; Smith and Walker Reference Smith and Walker2012; McKenzie and Rouse Reference McKenzie and Rouse2013; Swank and Fahs Reference Swank, Fahs, Dessel and Bolen2014). Specifically among LGBT people, qualitative studies suggest that lesbians, gays, and bisexuals who can integrate their sexuality and Christian religious beliefs (i.e., overcome religious stigmatization) report higher participation rates in gay-affirming churches, and likely express increased political activism (Rodriguez and Ouellette Reference Rodriguez and Ouellette2000; Minwalla et al. Reference Minwalla, Rosser, Feldman and Varga2005; Schnoor Reference Schnoor2006; McQueeney Reference McQueeney2009).

Recent survey data suggest that LGBT people are significantly less likely to identify with a religious tradition than non-LGBT people (Newport Reference Newport2014; Murphy Reference Murphy2015; Pastrana, Battle, and Harris Reference Pastrana, Battle and Harris2017). Given the association between hostile attitudes toward LGBT identity and conservative religious traditions, this is intuitive (Norton and Herek Reference Norton and Herek2013). In the extant literature, however, religiosity has not been associated with political activism among LGBT people. For example, while noting the lack of religious affiliation among members of LGBT activist groups, Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank, Fahs, Dessel and Bolen2014) contend religiosity weakens political activism on behalf of LGBT people (see also Jennings and Anderson Reference Jennings and Anderson2003; Lewis, Rogers, and Sherrill Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011). Their study is limited by a small (n = 159) non-representative sample of non-LGBT college students.

Other studies of political activism among LGBT people suggest that traditional resource variables have a negligible effect (Swank and Fahs Reference Swank and Fahs2013a; Reference Swank and Fahs2013b; Reference Swank and Fahs2012). Instead, Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank and Fahs2013a; Reference Swank and Fahs2013b) note membership in LGBT organizations or community centers is the most significant predictor of sexual minority political participation. Like Harris’ (Reference Harris1994) study of African-American churches, Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank and Fahs2013a, 1385) posit that these “mobilizing structures” allow for the transmission of certain cognitive resources such as perceived political efficacy, “outness,” shared political grievances, and even experience with stigmatization, which motivate political participation. While Swank and Fahs’ (Reference Swank and Fahs2013a, 1386) assertions are tested only in relation to LGBT community centers, they do suggest that “joining…a gay friendly church” may function in much the same way by “sensitize(ing) participants about shared grievances and enhance(ing) group solidarity.” If religiosity functions as a cognitive political resource, then I expect H1: Religious affiliation is related to higher group consciousness and “outness” among LGBT people; and H2: After controlling for these cognitive resources, religiosity and denominational affiliations will not be significantly related to political participation among LGBT people.

In the present study, I am interested in the relationship between religious-based sexual stigma, what I conceptualize as religious and sexual identity conflict, and political participation. While many studies identify stigmatization as a significant positive predictor of political engagement, it is widely recognized that “simply being a member of a stigmatized group is not enough to spur individual action” (Duncan, Mincer, and Dunn Reference Duncan, Mincer and Dunn2017, 1070; see also Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malenchuk1981; Lein Reference Lien1994; Swank and Fahs Reference Swank and Fahs2013a; Reference Swank and Fahs2013b; Reference Swank and Fahs2012). Indeed, the identity-threat model of stigmatization “posits that when a person with a stigmatized identity confronts a situation that seems to threaten one's identity,” such as a religious LGBT person confronting conflict between religious belief and sexuality, “the person will respond by attempting to decrease the threat” (Sevelius Reference Sevelius2013, 676). In terms of participation in LGBT political activities, the theory suggests that sexual minorities will attempt to lessen the threat of identity conflict by avoiding political activity altogether. Because LGBT people who “hid(e) their sexual identities” are “less inclined to join political protest,” (Swank and Fahs Reference Swank, Fahs, Dessel and Bolen2014, 63), it is expected that, H3: Conflict between religious beliefs and sexuality is negatively associated with political participation among LGBT people.

RELIGION, RESOURCES, AND INTERSECTIONALITY

From a resource perspective, socially constructed identity categories such as race, ethnicity, and gender are important indicators of economic resources because these categories represent economically disadvantaged groups in society. African Americans, for example, experience higher rates of unemployment, incarceration, and even mortality, along with lower incomes than Whites in the United States. Similarly, gendered workplace discrimination means that the economic resources available to cisgender men are denied to many women. Furthermore, social and economic disadvantages can be magnified for intersectionally marginalized individuals, such as women of color or lesbian women (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991). Resource-based models of political participation, then, may reflect societal trends of race- and gender-based economic inequality.

Aside from the differential availability of economic resources, religiosity is an important cultural feature, the importance and practice of which often varies in relation to race, ethnicity, and gender. This, too, has important political implications, especially in defining standards of sexual normalcy and the subsequent stigmatization of homosexuality in communities of color. Green (Reference Green, Lillian and Beverly1995, 43–8), for example, notes how White-dominated society perpetuates racists stereotypes of African Americans as promiscuous and how, when combined with the strong presence of “Western Christian religiosity,” this produces an environment that constraints expressions of “deviant” sexualities among Black LGBT people.

Intersectional studies suggest that racial, gender, and sexual minorities “reside in multiple systems of stratification,” which “constantly challenge” them to “simultaneously respond to numerous privileges and constraints that are bestowed on the various social roles they occupy” (Swank and Fahs Reference Swank and Fahs2013b, 661). In terms of religion, sexuality, and politics, this means that the effect of religion on political participation is necessarily experienced differently across socially constructed categories of race and ethnicity. Not only this, but the cognitive resources accrued through association with LGBT groups, for example, may be experienced differently (Harris Reference Harris1994). Indeed, (Cravens Reference Cravens2017) suggests that a sense of shared fate with the LGBT community is not as strong among those who do not represent the “prototypical” exemplar of the identity category, namely LGBT People of Color.

Without the appropriate data, it is difficult to model the intersectional effects of religion, race, and gender; however, from the perspectives of political resource theory and intersectionality, race and gender are significant predictors of political participation. For this reason, two data sets are used in this study to examine the effects of religion on political participation among LGBT people: one, a probability sample of LGBT people (Pew Research Center 2013); and the second, a convenience sample comprised predominantly of LGBT People of Color that allows for a more robust intersectional analysis (Social Justice Sexuality Project 2010).

RESEARCH DESIGN

The research design proceeds in two parts. First, to evaluate H1, I examine the relationship between religiosity and LGBT psychological resources using data collected from both a probability sample of 1197 self-identified LGBT adults living in the United States (Pew Research Center 2013) and a non-probability sample of over 5000 multi-racial self-identified LGBT adults in the United States (SJS 2010). I first present descriptive statistics for LGBT religious affiliation. After describing the operationalization of predictor and response variables, I present the results of tests of association between religious affiliation and the psychological resources “outness” and group consciousness.

Second, to analyze H2 and H3, I use the same data sets to examine the relationship between religiosity, denominational affiliation, identity conflict, and political participation. I first describe the operationalization of response and predictor variables as well as specific hypotheses associated with each independent variable. I then present the results of five ordinary least squares (OLS) regression estimations using additive indices of political activity as response variables (Aiken and West Reference Aiken and West1991). Finally, I conclude with a discussion of the results.

A NOTE ON DATA

Data for this study are taken from two national surveys of LGBT adults in the United States. The first, Pew Research Center (2013: Appendix A), was conducted by GfK Group using a “nationally representative online research panel” recruited through “a combination of random digit dialing and address-based sampling methodologies.” Of the more than 3,500 (3,645) panelists who self-identified as LGBT, just under 2,000 (1,924) were randomly selected to participate in the survey. Screening questions, which asked participants to reconfirm their sexual and gender identity, were used to determine eligibility, leaving a “final qualified sample” of 1,197. The survey instrument was self-administered and conducted entirely online with a completion rate of 74% and a cumulative response rate of 7.4% (Pew Research Center 2013: Appendix A)—a reasonable figure given “contemporary polling standards” (Weinberg, Freese, and McElhattan Reference Weinberg, Freese and McElhattan2014, 298). As Clifford, Jewell, and Waggoner (Reference Clifford, Jewell and Waggoner2015) note, such online-based survey platforms have proven a valid tool for testing social scientific hypotheses.

The second, SJS (2010), was conducted using a diverse sample of LGBT people recruited through “venue-based sampling, where research participants were sought at political, social, and cultural events; snowball sampling…; (and,) community partnerships” with LGBT social movement organizations (Pastrana, Battle, and Harris Reference Pastrana, Battle and Harris2017, 59). Survey instruments, in English or Spanish, were self-administered at “LGBT-of-color Pride marches, parades, picnics, religious gatherings, festivals, rodeos, senior events, and small house parties across the nation,” including Washington, DC and Puerto Rico (Battle, Daniels, and Pastrana Reference Battle, Daniels and Pastrana2015, 26). While the “purposive sample yielded over 5,500” completed surveys, the “total sample” consisted of just under 5,000 (n = 4,953) valid surveys (Battle, Daniels, and Pastrana Reference Battle, Daniels and Pastrana2015, 26). To “ensure reliability” of the survey instrument, many items “were taken word for word from other surveys” including the General Social Survey (GSS) and other LGBT-of-color national surveys (Battle, Daniels, and Pastrana Reference Battle, Daniels and Pastrana2015, 26).

Nevertheless, as Weinberg, Freese, and McElhattan (Reference Weinberg, Freese and McElhattan2014, 293) note “a diverse sample is not the same as a representative sample” when the “focus” is “estimating population parameters.” Weinberg, Freese, and McElhattan (Reference Weinberg, Freese and McElhattan2014, 308) also suggest that when “considering the possible generalizability of findings in a diverse but non-representative sample,” one should examine “broad characteristics” that are “known to diverge markedly between the sample and population.” A comparison of demographics between the two samples reveals some similarities that assist in the generalizability of the following analysis. For example, while the SJS (2010) sample appears to be more educated and more racially diverse, the samples achieve parity with regard to gender, income, and place of residence (i.e., rural/urban) (Pew Research Center 2013: Appendix A). While this alleviates some concern, the SJS (2010) data are used to more completely understand the political effects of religious and sexual identity incongruence among LGBT People of Color, which necessitates a data set with enough variation to make significant comparisons. The results below should be interpreted with caution if the intention is to generalize beyond the sample frame, a point I will reiterate in the final section.

Regarding religious measures in each survey, while the SJS (2010) was designed with the intention of capturing a “spirituality and religion” component of LGBT identity (Pastrana, Battle, and Harris Reference Pastrana, Battle and Harris2017), the Pew Research Center (2013) survey design offers only limited data on religious affiliation among LGBT people. In both cases, data for religious affiliation are only available at a broad categorical level, for example, Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, Atheist, etc., whereas more detailed denominational affiliations are considered individually identifiable information and are unpublished. When operationalizing denominational affiliation, therefore, the data merge some denominations (e.g., Evangelical, Mainline, and African-American Protestants), which might otherwise yield their own significant main effects. When possible, I include other measures, for example, when a participant indicates being “born again,” to capture this variation.

THE DISTRIBUTION OF QUEER RELIGION

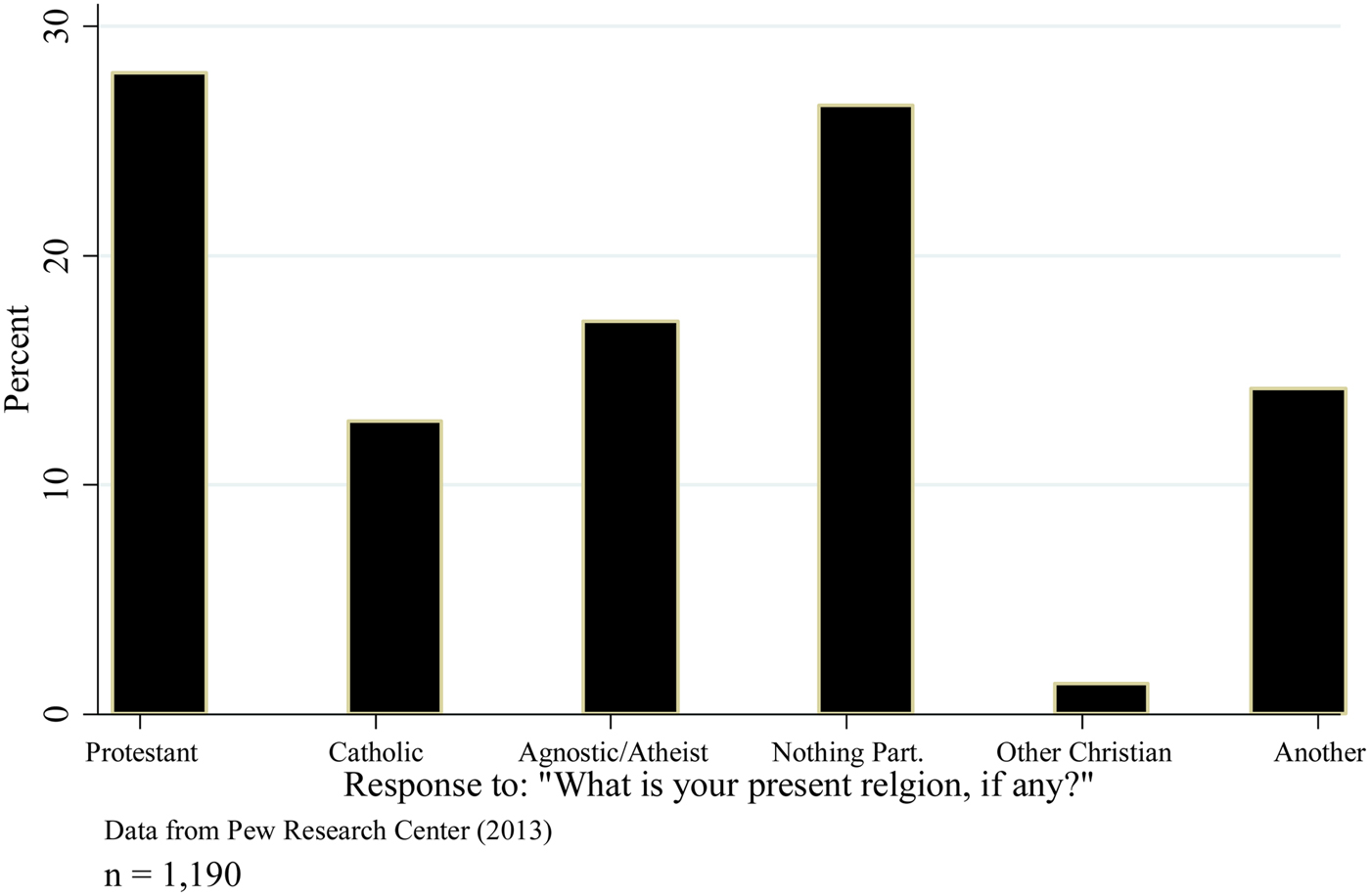

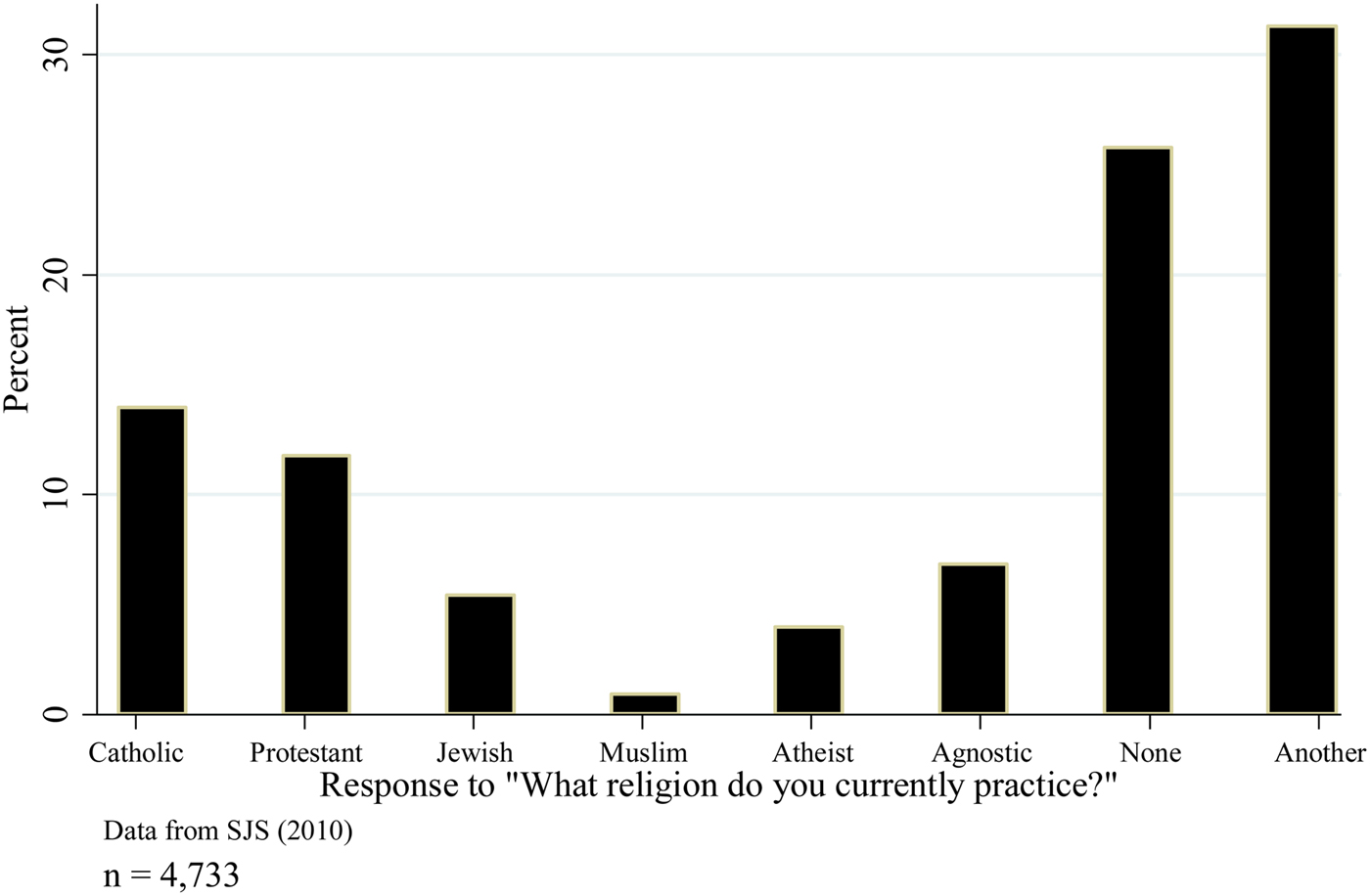

Previous research suggests that LGBT people are less religious than heterosexuals and less likely to identify with a specific faith tradition after publicly disclosing their sexual identity, or coming out (Egan, Edelman, and Sherrill Reference Egan, Edelman and Sherrill2008; Newport Reference Newport2014; Murphy Reference Murphy2015). How common then is religious belief among LGBT people? Figures 1 and 2 graphically depict the distributions of religious affiliation among LGBT people in the two samples. As Figure 1 shows, a plurality of respondents (43.6%) in the first sample indicate no specific religious affiliation or identify as atheist when asked “What is your present religion, if any?” (Pew Research Center 2013). A similar distribution is indicated by Figure 2 in the second sample among responses to the question “What religion do you currently practice?” (SJS 2010) (see Appendix A for all original questions and response sets). However, as both figures demonstrate, a majority of survey participants indicate some religious affiliation.

Figure 1. Distribution of religious denominations. Data from Pew Research Center (2013) n = 1,190.

Figure 2. Distribution of religious denominations. Data from SJS (2010) n = 4,733.

In both cases, Protestant Christianity and Catholicism are prominent faith traditions. Included in the “another” category in Figure 1 are minority faith traditions such as Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Orthodox, and even Unitarianism and Mormonism (Pew Research Center 2013). As Figure 2 shows, religious traditions other than Christianity, including Judaism and Islam are categorically represented and appear in greater frequency among the non-random sample. Data limitations, however, prevent greater specificity in describing the “another” category. This is not inconsequential given this is the category with a plurality of responses. While previous research suggests that LGBT people are less religious than heterosexuals, it is clear from both figures that religious affiliation is, in fact, common among LGBT people.

RELIGIOSITY AND LGBT PSYCHOLOGICAL RESOURCES

Having established that religious affiliation is more common among LGBT people than, perhaps, social science realizes, I now evaluate H1, that is, Religious affiliation is related to higher group consciousness and “outness” among LGBT people. To test the effects of religiosity on the accumulation of psychological resources relevant to political participation, I examine tests of association between two response indicators and a series of dichotomous indicators for denominational affiliation. Outness measures the extent to which one is publicly known to be LGBT; whereas, group consciousness measures the extent to which one psychologically identifies with LGBT people.

From the Pew Research Center (2013) data, the outness index is operationalized as a scale (α = 0.811) derived from two batteries of questions which, first, ask survey participants to identify whether they are openly LGBT to a series of familial and social figures. A second battery asks participants to identify on a scale from “none” to “all,” “how many of the important people in your life,” and “how many people you work closely with are aware” of your sexuality, and, finally, “how many of your close friends are LGBT” (Pew Research Center 2013). The scale ranges from 0 to 10. Large numbers represent higher levels of outness (see Appendix B for descriptive statistics).

Also from the Pew Research Center (2013) data, group consciousness is operationalized as an index (α = 0.802) derived from three questions that ask survey participants to indicate on a scale from “not at all” to “a lot,” “how much you share concerns and identity with” gay men, lesbians, and transgender people (Pew Research Center 2013). The scale ranges from 0 to 12. Large numbers on the index represent greater group consciousness.

Similarly, from the SJS (2010) data, “outness” and group consciousness are, again, operationalized as additive indices. The outness index (α = 0.893) is operationalized from a six-item battery that asks participants to indicate, on a scale from “none” to “all,” how many family members, friends (whether in real life or on social media), co-workers, neighbors, or fellow religious congregants the respondent is “out to” (SJS 2010). The scale ranges from 2 to 54. Again, large numbers represent greater outness. Group consciousness (α = 0.698) is operationalized from three items that ask respondents to indicate, on a scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” agreement with the statements: “I feel connected to my local LGBT community,” “I feel that the problems faced by the LGBT community are also my problem,” and “I feel a bond with other LGBT people,” and one item that asks respondents, on a scale from “not important at all” to “extremely important,” how much their sexual orientation “is an important part of your identity” (SJS 2010). The scale ranges from 1 to 36, where large numbers represent greater group consciousness.

From both data sets, dichotomous denominational predictor variables are operationalized from the categorical variable described above. The variable takes on a value of “0” when participants indicate no specific religious affiliation or identify as atheist, and a value of “1” when respondents identify as either Protestant, Catholic, or another faith tradition. In the case of the SJS (2010) data, dichotomous indicators are also operationalized for Jewish and Muslim participants.

Political resource theory suggests that LGBT people who affiliate with a specific religious tradition are more likely to accrue cognitive resources than LGBT people who do not identify as religious. Tables 1 and 2 show the results of the tests of association and describe the distribution of cognitive resources among religious LGBT people.

Table 1. Cognitive resources among sexual minorities who identify as religiousa

a Data from Pew Research Center (2013).

**p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.01.

Table 2. Cognitive resources among sexual minorities who identify as religiousa

a Data from SJS (2010).

*p ≤ 0.1; **p ≤ 0.05; *** p ≤ 0.01.

As Table 1 indicates, the relationship between religious affiliations, outness, and group consciousness are statistically significant at the 99% and 95% confidence levels, respectively. In this case, religious affiliation is not associated with an increase in the psychological resources of group consciousness or outness. Specifically, among the first sample, significant t-values (t = 1.64, p = 0.047; t = 3.96, p = 0.000) suggest that non-religious LGBT people (n = 520, M = 6.41) exhibit higher scores on the group consciousness scale than both Protestant (n = 333, M = 6.15) and Catholic (n = 152, M = 5.59) LGBT people. Similarly, significant t-values (t = 2.32, p = 0.010; t = 3.20, p = 0.000) suggest that non-religious LGBT people (n = 520, M = 15.7) exhibit higher scores on the outness scale than both Protestant (n = 333, M = 15.1) and Catholic (n = 152, M = 14.5) LGBT people.

Table 2 reveals a similar relationship, in that group consciousness is significantly related to religious affiliation at the 90% and 95% confidence levels using data with an oversample of racial minorities. Specifically, significant t-values (t = 2.08, p = 0.018; t = 1.47, p = 0.07; t = 2.82, p = 0.002) suggest that non-religious LGBT people (n = 1,706, M = 16.8) exhibit higher scores on the group consciousness scale than Catholic (n = 648, M = 16.3), Jewish (n = 253, M = 16.3), and Muslim (n = 44, M = 14.7) LGBT people. While, significant t-values (t = 4.18, p = 0.000; t = 5.49, p = 0.000; t = 4.14, p = 0.000; t = 2.53, p = 0.005) suggest that non-religious LGBT people (n = 1,683, M = 26.1) exhibit higher scores on the outness scale than Protestant (n = 537, M = 23.8), Catholic (n = 647, M = 23.5), Muslim (n = 44, M = 19.9), and other religiously affiliated (n = 1,440, M = 25.3) LGBT people.

Consistent with Lewis, Rogers, and Sherrill (Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011), outness is negatively associated with religious affiliation among Protestants and Catholics across both samples, while the negative association extends across all religious traditions except Judaism in the second sample. The relatively small proportion of Muslim survey participants, however, may temper this finding. In five cases, non-religious sexual minorities psychologically associate with their LGBT identity more closely than religious sexual minorities. Again, Catholics across samples show less LGBT group consciousness, while Protestants in the first sample and Muslim and Jewish participants in the second sample exhibit similar patterns. The data here indicate religious affiliation does not appear to convey the psychological resources of outness and group consciousness, which are positively associated with political participation, in the same way as LGBT organizational membership and H1 is not supported.

QUEER IDENTITY AND RELIGIOUS CONFLICT

Before proceeding to an exploration of H2 and H3, having established the prominence of religious affiliation among sexual minorities, it is also important to quantify the extent to which sexual minorities feel conflict between their sexual and religious identities. Figures 3 and 4 graphically depict the distribution of religious and sexual identity conflict by specific denomination after all responses are collapsed into the four most common categories from both data sets: non-religious/atheist, Protestant, Catholic, or another religious denomination. Conflict is operationalized as a dichotomous indicator from questions that ask if respondents “feel there is a conflict between your religious beliefs and your sexual orientation/gender identity” (Pew Research Center 2013) or to what extent one's religious tradition is a “negative or positive influence for you in coming to terms with your LGBT identity” (SJS 2010).

Figure 3. Distribution of religious and sexual identity conflict by denominational affiliation. Data from Pew Research Center (2013) n = 1,187.

Figure 4. Distribution of sexual and religious identity conflict by denominational affiliation. Data from SJS (2010) n = 2,784.

Overall, almost one-quarter (24.2%) of the Pew Research Center (2013) sample indicate experience with religious and sexual identity conflict. As Figure 3 shows, Protestants report the most experience with conflict, although slightly <10% of both Protestants and Catholics indicate experience with identity conflict. While those who identify as non-religious/atheist report less experience with identity conflict, slightly more than 5% of this group experience the phenomenon, suggesting at some point in their lives, those who identify as non-religious or atheist likely identified as religious and, perhaps, still experience religious-based concerns over their sexual identity.

Roughly the same proportion of the SJS (2010) sample, almost one-quarter (22.3%), indicate experience with sexual and religious identity conflict. As Figure 4 shows, among the SJS (2010) data, while Protestants and Catholics still exhibit identity conflict, those who identify with other religious traditions and especially those who identify as non-religious or atheist exhibit more identity conflict. This finding can be attributed to a number of possible explanations. First, the finding regarding the “another” category is likely due to the larger proportion of the sample that identifies as Jewish, Muslim, or another non-Christian religious denomination. Although the data do not provide detailed categorical descriptors, it may also be that ethnic minority Christian traditions are over-represented in the sample and contribute to the increase in conflict within the “another” category. Second, regarding conflict among those who identify as non-religious or atheist, as previously described, the indicator is derived from a question that measures the extent to which religion was a positive or negative influence on an individual “coming to terms with” their sexual identity. Figure 4, then, likely reflects a post-coming out shift in religious identity toward religious non-affiliation. Such a scenario is consistent with Lewis, Rogers, and Sherrill (Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011) and the graphic depiction in Figure 3.

The findings thus far indicate religious affiliation is more common among LGBT populations than previously considered. However, religious affiliation alone is not positively associated with either of two psychological resources associated with LGBT political participation, group consciousness, or outness. Furthermore, the data suggest that roughly one-quarter of LGBT people experience conflict between their religious and sexual identities. I now turn to an examination of H2 and H3, that is, Controlling for cognitive resources, religiosity, and denominational affiliations will not be significantly related to political participation among LGBT people; and H3: Conflict between religious beliefs and sexuality is negatively associated with political participation among LGBT people.

RELIGIOSITY, CONFLICT, AND LGBT POLITICAL PARTICIPATION

The identity-threat model of stigmatization suggests that when sexual minorities experience conflict between their religious and sexual identities, they will attempt to diminish the threat posed by the conflict through avoidance (Sevelius Reference Sevelius2013). The likely consequence for political engagement is a reduction in political participation. In the following sections, I test this theory with OLS regression analyses using dependent variables operationalized as additive indices of political activity. For each data set, I describe the operationalization of response and predictor variables and then the results of OLS model estimation.

ANALYSIS 1: REPRESENTATIVE SAMPLE

From the Pew Research Center (2013) data, political participation is operationalized from a six-item battery measuring participation in LGBT-specific political activities and two questions related to voting behavior. First, survey participants are asked to indicate, on a scale from “always” to “seldom,” how often they vote (Pew Research Center 2013). Second, participants are asked to indicate their voter registration status on a scale from “absolutely certain I am registered” to “I am not registered” (Pew Research Center 2013; see Appendix A for original questions and response sets).

Three questions relate to political activity through financial means. Specifically, participants are asked to indicate if they have “bought a certain product or service because the company that provides it is supportive of LGBT rights; decided NOT to buy a certain product or service because the company that provides it is not supportive of LGBT rights; or donated money to politicians or political organizations because they are supportive of LGBT rights” (Pew Research Center 2013). Response sets are collapsed into dichotomous categories that take on the value of “0” when survey participants indicate they have not participated in the activity and a value of “1” otherwise.

Three other questions relate to political activity through volunteerism. Specifically, participants are asked if they have “been a member of an LGBT organization; attended a rally or march in support of LGBT rights; or attended an LGBT Pride event” (Pew Research Center 2013). Again, responses are collapsed into dichotomous categories that take on the value of “0” when survey participants indicate that they have not participated in the activity and a value of “1” otherwise. Responses are reverse coded when necessary to maintain scale consistency. The participation index (α = 0.799) ranges from 0 to 10, where large numbers represent more participation (see Appendix B for descriptive statistics).

INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

Consistent with the resource model, social capital, and identity-threat theories, a total of 13 independent variables are operationalized. In the following sections, I describe the operationalization of the variables as well as hypotheses associated with each (see Appendix B for a correlation matrix for independent variables from each analysis).

RESOURCE VARIABLES: INCOME, EDUCATION, AGE, AND UNEMPLOYMENT

The resource model of political participation suggests that personal wealth, education, and socioeconomic indicators of affluence are associated with political mobilization because these resources allow individuals the time and opportunity necessary to participate in the political process (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Lehman Schlozman1995). Furthermore, intersectionality suggests that structures of power interact to systemically deny the benefits associated with traditional socioeconomic resources to socially constructed categories of race, ethnicity, and gender in the United States, especially when these categories intersect (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991). Consistent with these approaches, I operationalize six independent variables: income, education, age, unemployment, race, and female.

Income, education, and age are discrete variables operationalized from questions measuring survey participants’ annual income, level of education, and age, respectively. Higher values of each variable indicate greater income, higher levels of education, and greater age, respectively. All three variables are expected to be positively associated with the participation index.

To further test the resource model, another indicator of socioeconomic affluence is operationalized as a “dummy” variable. The variable unemployment takes on the value of “0” if the survey participant indicates either full-time or part-time employment or retirement, and a value of “1” if the survey participant indicates not being employed and is expected to be negatively associated with the participation index.

Dichotomous indicators for race and gender are operationalized from questions that ask survey participants to identify their race, out of five possible categories including White, Black, Hispanic, Other, and 2+ races, and their gender. Intersectional studies suggest that women as well as racial and sexual minorities are not afforded equality of opportunity by the sexist and racist power structures that dominate American politics and society. Not only this, studies of racial and ethnic minority religious and cultural influence on political participation suggest that different cognitive resources accrue through religious participation (Harris Reference Harris1994). While more robust measures are constructed later, data limitations necessitate that these complex concepts be represented by dichotomous indicators. Race, therefore, takes on a value of “1” for respondents who indicate either Black, Hispanic, 2+ races, and other racial identities or a value of “0” otherwise. Similarly, female takes on a value of “1” for respondents who indicate their sex as female and “0” otherwise. Both variables are expected to be negatively associated with the participation index.

RELIGIOUS RESOURCES AND IDENTITY THREAT: RELIGIOSITY, DENOMINATION, AND CONFLICT

Religious affiliation and participation are thought to provide two types of resources. First, religious participation provides organizational resources, such as group leadership and public speaking, which easily translate to secular political action. Religious affiliation and participation are also thought to provide cognitive resources, such as group consciousness (Harris Reference Harris1994).

To test the effects of religious participation as well as specific denominational effects, two independent variables are constructed. First, religiosity is operationalized as an index (α = 0.803) derived from two questions that ask survey participants to rate the “importance of religion in your life,” on a scale from “very important” to “not at all important;” and “how often you attend religious services” on a scale from “never” to “more than once a week” (Pew Research Center 2013).

Second, a categorical denominational indicator (denomination) is operationalized from a question asking survey participants their “present religion” (Pew Research Center 2013). While Brooks and Manza (Reference Brooks and Manza2004) suggest a seven-category variable, due to data restrictions, the various responses are collapsed into the four categories previously described: Protestant, Roman Catholic, Other religious denomination, and non-religious. Finally, to parse out the denominational overlap, a dichotomous indicator (Evangelical) is operationalized from a question that askes only Christian respondents “would you describe yourself as “born again” or Evangelical Christian” (Pew Research Center 2013). Evangelical takes on a value of “1” if participants indicate they are born again and a value of “0” otherwise. Religiosity as well as Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Other religious denominations are expected to be positively associated with the participation index, while Evangelical is expected to be negatively related to the index.

Finally, sexual and religious identity conflict is operationalized as a dichotomous indicator from a question asking survey participants whether they feel conflict between their religious beliefs and their sexuality. It is expected that conflict is negatively associated with the participation index.

COGNITIVE RESOURCES: OUTNESS, GROUP CONSCIOUSNESS, AND STIGMATIZATION

Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank and Fahs2013a; Reference Swank and Fahs2013b; Reference Swank and Fahs2012) suggest that, among LGBT people, political participation is best predicted by cognitive resources, such as outness and group consciousness that accrue to members of LGBT interest groups. These resources help clarify shared political goals and instill political motivation. While they assert affiliation with or participation in gay-affirming churches would produce similar results, the assertion is not empirically tested and the data here suggest that certain religious LGBT people are less likely to accrue these psychological resources. Because I cannot explicitly examine the effects of affiliation with gay-affirming denominations, to determine if religious participation and affiliation produce different effects than LGBT interest group associations, the model specified in this study holds constant three cognitive resources that are believed to result from LGBT associations, outness, group consciousness, and stigmatization.

The outness index is operationalized as a scale (α = 0.811) described above. As the tests of association show, outness is not equally distributed among LGBT people. Aside from religious affiliation, outness also varies between racial and ethnic categories. Specifically, Grov et al. (Reference Grov, Bimbi, Nanin and Parsons2006) observe that Black gays and lesbians are less likely to be out to their families than are White gays and lesbians. This, again, illustrates the complex nature of the relationship between race, ethnicity, and sexuality and urges caution in interpretation of significant racial or ethnic effects using dichotomous indicators.

A second cognitive resource thought to be important in LGBT political mobilization is group consciousness. Group consciousness is operationalized as a scale (α = 0.802) described above. The outness index ranges from 0 to 24, while the group consciousness scale ranges from 0 to 12. Large numbers on the indices are associated with greater outness and group association, respectively. Both outness and group consciousness are expected to be positively related to the participation index.

A final cognitive resource available to LGBT people with implications for political participation is experience with stigmatization. Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank and Fahs2013a, 1385) note that “experiences of discrimination can delegitimize conventional norms and lead to an oppositional consciousness that challenges the status quo.” Stigmatization is operationalized as a scale (α = 0.771) derived from a battery of questions that present survey participants with six statements about discrimination such as, “been physically attacked,” “been subject to slurs,” and “been made to feel unwelcome in church,” and asks them to indicate whether they have experienced each (Pew Research Center 2013). Lower scores on the stigma index indicate fewer stigmatizing experiences. Stigmatization is expected to be positively associated with the participation index.

CONTROL VARIABLES

In addition to the variables above, three control variables are included in model estimations. First, partisan is operationalized as a dichotomous measure that takes on a value of “0” when respondents indicate no partisan political affiliation and a value of “1” when respondents indicate affiliation as either Republican, Democrat, or Independent. Secondly, conservative self-identification is operationalized from a question that asks respondents to identify their political ideology on a scale from “very liberal” to “very conservative” (Pew Research Center 2013). Low scores on the measure indicate conservatism, while high scores indicate liberalism. Finally, rural is operationalized as a dichotomous indicator that takes on the value of “0” when respondents indicate their residence in a “metro area” and a value of “1” otherwise (Pew Research Center 2013).

RESULTS

Table 3 shows the results of OLS regression estimation using the participation index as the response variable. Model 1 in Table 1 explains almost half of the variation in the dependent variable (r 2 = 0.485) and diagnostics reveal model residuals approximate normality (χ2 = 5.52, p = 0.063). Furthermore, there is no apparent problem with multicollinearity (mean VIF (variance inflation factor) = 1.34) or heteroscedasticity (F = 1.04, p = 0.417).

Table 3. OLS regression estimation, DV = participation index a

a Data from Pew Research Center (2013).

*p ≤ 0.1; **p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.01.

Consistent with the resource model, the coefficient estimates for education and age achieve statistical significance at the 99% confidence level, and the direction of the relationship is as predicted. That is, contrary to Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank and Fahs2013a), but consistent with the political resource hypothesis, education (β = 0.553, p = 0.000) and age (β = 0.461, p = 0.000) are positively related to political participation among sexual minorities.

Consistent with cognitive resource models, the coefficient estimates for outness (β = 0.212, p = 0.000), group consciousness (β = 0.095, p = 0.021), and experience with stigmatization (β = 0.564, p = 0.000) all achieve statistical significance at either the 99% or 95% confidence levels. As predicted, the confidence in one's sexual identity associated with being openly LGBT, a close psychological association with the LGBT community, and even experiencing stigmatizing treatment on the basis of one's sexual identity significantly motivate political participation.

H2 is only partially supported, however. While the categorical denominational indicators exhibit no statistical significance, the coefficient estimate for Evangelicalism (β = −0.519, p = 0.027) and religiosity (β = 0.079, p = 0.077) do achieve statistical significance, although the latter is not at traditional levels. Evangelicals, then, are less likely to engage in LGBT political activity, a finding consistent with Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank, Fahs, Dessel and Bolen2014). Concerning religiosity, the result may be contributed to the nature of religious participation measured by the index. That is, data limitations require the religiosity scale be composed of indicators for attendance. Contemporary research, however, suggests that only measuring attendance can “mask” the effects of religious participation on political participation (Driskell, Embry, and Lyon Reference Driskell, Embry and Lyon2008, 294).

Consistent with H3, the coefficient estimate for religious and sexual identity conflict is statistically significant, although not at traditional levels, and in the expected direction (β = −0.342, p = 0.088). That is, religious and sexual identity conflict is associated with a decrease in political participation even after controlling for religiosity, religious affiliation, and psychological resources such as outness and group consciousness.

ANALYSIS 2: INTERSECTIONAL PARTICIPATION

To better understand the nature of the relationship between racial, gender, and religious identities and their effect on political participation, it is necessary to conduct an analysis using data with a more robust sample of racial and gender minorities. As previously discussed, the SJS (2010) data represent a convenience sample of n = 4,953 survey participants, the majority of which identify as a racial or ethnic minority.

In an important contribution to the multi-issue activism literature, the SJS (2010) distinguishes between participation in activities for LGBT people, People of Color, and LGBT People of Color (Anderson and Jennings Reference Anderson and Jennings2010). Participants are presented with a series of three statements about their participation in political activity based on these specific characteristics and asked to rate, on a scale from “never” to “more than once a week,” how often they take part in “political events, social or cultural events, or donated money to an organization” (SJS 2010; see Appendix A for original survey question and response sets).

From these items, political participation is operationalized along four dimensions using additive indices. First, LGBT participation (α = 0.737), people of color (POC) participation (α = 0.840), and LGBT POC participation (α = 0.755) are constructed as scale measures of political engagement based on sexual and racial identity. Second, an aggregate measure of political participation, the participation index (α = 0.874), is operationalized as a scale including the previous items as well as a dummy measure indicating that a participant voted in the 2008 presidential election. The identity-based scales range from 0 to 18, while the aggregate measure ranges from 1 to 91, where large numbers indicate more participation.

INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

Again, political resources are measured using indicators for income, education, and employment. Due to the unavailability of data, however, age is excluded from the analysis. The robustness of the data, however, allows for a more nuanced examination of both race and gender. Race is operationalized using a series of dichotomous indicators that take on a value of “1” if the respondent indicates their racial identity is Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, White, or Multi-Racial, and a value of “0” otherwise. Similarly, the robustness of the data allows for a more nuanced measure of gender. In addition to a dichotomous female indicator, a dichotomous indicator for cisgender is also included that takes on a value of “1” if a respondent indicates they identify as gender non-conforming or transgender and a value of “0” otherwise.

The SJS (2010) data also allow for a more robust measure of religiosity. Whereas analysis 1 relied on a measure constructed primarily from indicators for service attendance, in analysis 2, religiosity is operationalized as an additive index from five items that ask participants to indicate agreement, on a scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” with the statements “I pray daily,” “I look to my faith as providing meaning and purpose in my life,” “I consider myself active in my faith or religious institution,” “I enjoy being around others who share my faith,” and “My faith impacts many of my decisions” and one item that measures religious service attendance from “never” to “every week” (SJS 2010). The resultant scale (α = 0.883) ranges from 1 to 54, where lower numbers represent less religiosity.

Religious denomination is operationalized by collapsing a multi-response item into a six-category measure denoting Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, other religious, and no religious affiliation. Due to data limitations, there is no available measure for Evangelicalism. Also, whereas religious and sexual identity conflict was previously operationalized as a dichotomous indicator in analysis 1, in analysis 2, conflict is operationalized from an item that asks respondents to identify the nature of the influence, on a scale from negative to positive, their “religious tradition or spiritual practice” has been on “coming to terms with” their “LGBT identity” (SJS 2010).

Finally, outness, group consciousness, and stigmatization are, again, operationalized as additive indices. The outness (α = 0.893) and group consciousness (α = 0.698) indices are operationalized from a six-item and three-item battery described above, while stigmatization (α = 0.739) is operationalized from a battery of three items that ask respondents to indicate their agreement, from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” with the statements: “Homophobia is a problem within my racial or ethnic community,” “Homophobia is a problem within my neighborhood,” and “In general, homophobia is a problem within all communities of color” (SJS 2010).

RESULTS

Table 4 shows the results of OLS regression estimation using the participation index derived from the SJS (2010) as the dependent variable. As Table 4 shows, model 2 explains about 14% of the variation in the dependent variable (r 2 = 0.139). While diagnostics show the model residuals approximate normality (χ2 = 783.1, p = 0.000) and no problem with multicollinearity (mean VIF = 1.47), there appears to be an issue with heteroscedasticity (F = 4.08, p = 0.000). For this reason, model 2 is estimated with robust standard errors.

Table 4. OLS regression estimation, DV = participation indexa

a Data from SJS (2010).

b Model estimated with robust standard errors.

*p ≤ 0.1; **p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.01.

Before explaining the results, it is important to recognize that the data used in this analysis are derived from a convenience sample of primarily LGBT People of Color, which may influence the strength and direction of the relationships presented. Again, consistent with the resource models of participation, the coefficient estimate for income is statistically significant at the 99% confidence level (β = 0.221, p = 0.000) and positively associated with participation. Also, the coefficient estimates of three racial identity indicators achieve statistical significance at the 95% confidence level, but exhibit differing directionalities. Specifically, a positive coefficient estimate indicates that Black respondents are more likely than others in the sample to participate in politics (β = 1.39, p = 0.003), while negative coefficient estimates indicate that Asian or Pacific Islanders (β = −1.96, p = 0.018) and Whites (β = −1.66, p = 0.020) are significantly less likely to participate in the political activities specified by the dependent variable. Furthermore, although the cisgender dummy variable fails to achieve statistical significance, the coefficient estimate for sex is significant at the 99% confidence level (β = −1.90, p = 0.000) and negatively associated with the dependent variable, meaning men in the sample are more likely to participate in politics than women.

While the coefficient estimate for stigmatization does not achieve statistical significance, again, LGBT psychological resources are significant predictors of political behavior. Specifically, model 2 in Table 4 shows that the coefficient estimates for outness (β = 0.046, p = 0.023) and group consciousness (β = 0.498, p = 0.000) are statistically significant at the 95% and 99% confidence levels, respectively, and positively associated with the dependent variable.

Consistent with the findings of model 1 in Table 3, but contrary to H2, after controlling for economic and psychological resources, religious participation remains an independent, statistically significant, predictor of political behavior. As model 2 shows, the coefficient estimate for religiosity is significant at the 99% confidence level (β = 0.269, p = 0.000) and positively associated with the dependent variable. Also consistent with model 1, and with H3, the coefficient estimate for religious and sexual identity conflict achieves statistical significance at the 99% confidence level (β = −0.294, p = 0.009) and is negatively associated with political participation. Finally, while statistically significant at the 95% and 90% confidence levels, respectively, Protestantism (β = −1.58, p = 0.031) and Jewish religious affiliations (β = −1.41, p = 0.043) are negatively associated with the dependent variable. That is, Jewish LGBT people and LGBT Protestants are less likely than non-religious LGBT people to participate in political activity.

SEXUAL AND RACIAL MINORITY POLITICAL PARTICIPATION

While analyses of scale measures of political participation provide a general understanding of the nature of the relationship between religiosity and LGBT politics, the SJS (2010) data allow for a more nuanced examination of multi-issue activism or “overlapping issue involvement” (Anderson and Jennings Reference Anderson and Jennings2010, 63). In the following sections, I present the results of regression modeling using dependent variables that represent LGBT and POC-specific political behaviors.

Table 5 shows the results of OLS regression estimation using the LGBT participation, POC participation, and LGBT POC participation indices as the dependent variables. Like model 2, the residuals in each model approximate normality and there appear to be no problems with multicollinearity; however, because diagnostics reveal heteroscedasticity in each model, models 3–5 are estimated with robust standard errors.

Table 5. OLS regression estimation, DV = LGBT participation index, POC participation index, and LGBT POC participation indexa

a Data from SJS (2010).

b Model estimated with robust standard errors.

*p ≤ 0.1; **p ≤ 0.05; ***p ≤ 0.01.

As Table 5 shows, religiosity is a consistent positive predictor across all three aspects of political participation at the 99% confidence level. Contrary to H2, ceteris paribus, LGBT people who participate in religious activities are more likely to engage in politics. Although as predicted, on the other hand, religious and sexual identity conflict is significantly associated with decreased political participation. This pattern only seems to hold in relation to LGBT political activity, however. As model 4 in Table 5 shows, religious and sexual identity conflict is not a significant predictor of participation in organizations for People of Color. Similarly, specific denominational effects are only statistically significant in predicting LGBT-related political activity. As models 3 and 5 in Table 5 show, Protestant and Catholic LGBT people are less likely to participate in political activity for LGBT-specific causes, while a negative relationship with participation is observed at the intersection of Jewish religious affiliation and POC activism.

As Table 5 shows, income and sex are also consistent predictors of political participation. The directionality of the coefficient estimates in each model is also consistent with the resource hypothesis. That is, income and those with access to economic resources due to an advantaged social identity are better equipped to engage in political activity. Finally, independent of religious effects, group consciousness and outness are also consistent positive predictors of political participation. Taken with the associational findings presented above, it is likely that LGBT people do not accrue these psychological resources from religious participation, but instead, as Swank and Fahs (Reference Swank and Fahs2013a; Reference Swank and Fahs2013b; Reference Swank and Fahs2012) suggest, they are transmitted through group associations that explicitly affirm one's sexual or gender minority identity.

Finally, racial identity exhibits an independent effect from the religiosity measure used in these analyses. As models 4 and 5 in Table 5 show, rather than reducing the likelihood of participation for racial minorities, a Black identity, specifically, greatly increases the likelihood of participating in POC and LGBT POC political activities. Conversely, a White and Asian or Pacific Islander identity are both associated with significantly less political engagement in activities for People of Color. This suggests that multi-issue political activism among LGBT people is motivated by racial identity as much as prior political involvement in politics as Anderson and Jennings (Reference Anderson and Jennings2010) suggest.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The goal of this study is to examine the effects of religiosity on political participation among LGBT people. The extant social scientific literature characterizes religiosity and sexuality as engaged in a culture war over civil rights and the very definition of sexuality and gender in American law and society (Fiorina, Abrams, and Pope Reference Fiorina, Abrams and Pope2005). This characterization often assumes that a sexual or gender minority identity and religious faith are incompatible. This is true in some cases. As the data here show, roughly one-quarter of sexual minorities experience the phenomenon of identity conflict. The data also show, however, that religious belief is a dominant feature of the sexual and gender minority experience.

This study proposes three overarching hypotheses, H1: Religious affiliation is related to higher group consciousness and “outness” among LGBT people; H2: After controlling for these cognitive resources, religiosity and denominational affiliations will not be significantly related to political participation among LGBT people; and H3: Conflict between religious beliefs and sexuality is negatively associated with political participation among LGBT people.

H1 is not supported by the preceding analysis. The data in Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate that Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, and Muslim LGBT people are out to significantly fewer people and exhibit less LGBT group consciousness. The analysis here is consistent with the studies linking atheism/agnosticism and “outness”, and further suggests that the prevalence of religious non-affiliation, agnosticism, or atheism among sexual minorities is likely due to conflict between religious doctrine and sexuality (Lewis, Rogers, and Sherrill Reference Lewis, Rogers and Sherrill2011). Furthermore, after coming out, and even after disassociating with specific religious traditions, the data in Figures 3 and 4 suggest that religious and sexual identity conflict may persist, with significant consequences for political behavior.

If religiosity enables the accrual of cognitive resources among LGBT people that augment political participation, then it would be intuitive to suggest that when controlling for these resources, religiosity would show no significant effect on political participation. However, just as H1 is not supported by the preceding analysis, neither is H2. After controlling for the effects of psychological resources, religiosity consistently exhibits a positive effect on political participation among LGBT people. Ceteris paribus, religious LGBT people are more likely to participate in politics, suggesting that the religious resource model does hold among sexual minorities. This finding is tempered, however, by specific denominational effects. Consistent with previous research, data from the probability sample reveal that Evangelical Christianity is negatively associated with political participation among LGBT people. Data from the non-probability sample suggest further denominational effects especially among Protestant and Jewish LGBT people. With no control for Evangelical Protestantism, it may be that the aggregate Protestant indicator used in models 2–5 is expressing a similar relationship as Evangelicalism in model 1. By deconstructing the participation index, however, the nuances of religious affiliation can be explored as Jewish, White, and Asian or Pacific Islander LGBT people in the SJS (2010) sample that are significantly less likely to participate only in the activities for LGBT People of Color.

Concerning psychological resources, this study contributes to our understanding of multi-issue activism as LGBT group association appears to reflect a sense of political solidarity that extends beyond sexual minorities to other marginalized groups in society. Not that all LGBT people are more politically empathetic, but those LGBT people with a strong sense of group consciousness, that is, who feel strongly connected to the LGBT community and movement, are likely more aware of the multiplicity of disadvantages imposed on minority groups simply because of their minority identity. This awareness, in turn, motivates participation in political activity that endeavors to mitigate or end societal inequalities.

Finally, the evidence here supports H3. Religious and sexual identity conflict consistently exerts a negative influence on political participation. Troublingly, the size of the effects across the four models in which the conflict coefficient achieves statistical significance suggests that identity conflict has the potential to mitigate any positive participatory effects of religiosity. Future research should explore the issue of identity/religious conflict within the context of LGBT-affirming congregations to determine if the trend observed here persists.

This study is limited in a number of ways that implore caution when generalizing the results. First, data from both samples are collected through online survey instruments. While recent research confirms the validity of such instruments, it is also the case that “personality affects self-selection into online panels” and the results could be biased by an overly politically active sample (Clifford, Jewell, and Waggoner Reference Clifford, Jewell and Waggoner2015, 2). This may especially be true among the non-probability sample and its reliance on LGBT and POC organizations and events for participant recruitment.

Furthermore, the SJS (2010) uses a non-probability sample frame. While there are some general similarities between the two data sets used in this study, because the SJS (2010) data set intentionally oversamples LGBT People of Color, the results are necessarily skewed and not readily generalizable beyond the sample. As Battle, Daniels, and Pastrana (Reference Battle, Daniels and Pastrana2015) and Pastrana, Battle, and Harris (Reference Pastrana, Battle and Harris2017) demonstrate, the internal validity of the data combined with the unique perspective provide a lens through which to examine the intersectional effects of race, religion, sexuality, and politics. Future survey research should build on this design in producing externally valid survey instruments.

Finally, while this is an exploration of religion among LGBT people, the preceding analysis is limited by data and assumptions about LGBT people of faith that do not allow for a more thorough explication of religious affiliations. Namely, the data are limited to broad labels of faith traditions, even though it is widely understood that significant variation exists at the denominational level and, as evidenced by the significance of Evangelicalism in this study, is likely a significant source of variation among LGBT people.

The Pew Research Center bears no responsibility for the analyses or interpretations of the data presented here.

Appendix A Original Survey Questions and Response Sets

Pew Research Center (2013)

Participation Index

Here are a few activities some people do and others do not. Please indicate whether or not you have done this each of the following: (KEEP IN ORDER).

a. Been a member of an LGBT organization

b. Bought a certain product or service because the company that provides it is supportive of LGBT rights

c. Decided NOT to buy a certain product or service because the company that provides it is not supportive of LGBT rights

d. Attended a rally or march in support of LGBT rights

e. Attended an LGBT Pride event

f. Donated money to politicians or political organizations because they are supportive of LGBT rights

RESPONSE CATEGORIES

1 Yes, in past 12 months

2 Yes, but not in past 12 months

3 No, never done this

How often would you say you vote …

1 Always

2 Nearly always

3 Part of the time

4 Seldom

Which of these statements best describes you?

1 I am absolutely certain that I am registered to vote at my current address

2 I am probably registered, but there is a chance my registration has lapsed

3 I am not registered to vote at my current address

Resources:

Income

Last year, that is, in 2012, what was your total family income from all sources?

1 Less than $20,000

2 $20,000 to under $30,000

3 $30,000 to under $40,000

4 $40,000 to under $50,000

5 $50,000 to under $75,000

6 $75,000 to under $100,000

7 $100,000 to under $150,000

8 $150,000 or more

Education

Respondent educational attainment

1 Less than high school

2 High school

3 Some college

4 Bachelor's degree or higher

Age

Respondent age

1 18–24

2 25–34

3 35–44

4 45–54

5 55–64

6 65–74

7 75+

Unemployment

Which best describes your current situation?

1 Employed full-time

2 Employed part-time

3 Retired

4 Not employed for pay

Racial Minority

Respondent race/ethnicity

1 White, Non-Hispanic

2 Black, Non-Hispanic

3 Other, Non-Hispanic

4 Hispanic

5 2+ Races, Non-Hispanic

Female

Are you…

1 Male

2 Female

Religiosity Scale

How important is religion in your life?

1 Very important

2 Somewhat important

3 Not too important

4 Not at all important

Aside from weddings and funerals, how often do you attend religious services…?

1 More than once a week

2 Once a week

3 Once or twice a month

4 A few times a year

5 Seldom

6 Never

Religious Denomination

What is your present religion, if any? Are you…

1 Protestant

2 Roman Catholic

3 Agnostic or Atheist

4 Nothing in particular

5 Christian (VOL.)

6 All others, including: Mormon, Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, Unitarian, or Something else

Conflict

And thinking about your own religious beliefs, do you personally feel that there is a conflict between your religious beliefs and your (INSERT FOR LGB: sexual orientation, FOR T: gender identity)?

1 Yes, conflict

2 No, no conflict

Outness Index

Did you ever tell your mother about your (INSERT FOR LGB: sexual orientation, FOR T: gender identity)?

1 Yes, told my mother

2 No, did not tell my mother

3 Not applicable

Did you ever tell your father about your (INSERT FOR LGB: sexual orientation, FOR T: gender identity)?

1 Yes, told my father

2 No, did not tell my father

3 Not applicable

Did you ever tell any sisters about your (INSERT FOR LGB: sexual orientation, FOR T: gender identity)?

1 Yes, told one or more sisters

2 No, did not tell any sister(s)

3 Not applicable

Did you ever tell any brothers about your (INSERT FOR LGB: sexual orientation, FOR T: gender identity)?

1 Yes, told one or more brothers

2 No, did not tell any brothers(s)

3 Not applicable

Have you told any close friends about your (INSERT FOR LGB: sexual orientation, FOR T: gender identity)?

1 Yes, told one or more close friends

2 No, did not

Have you ever revealed your (INSERT FOR LGB: sexual orientation, FOR T: gender identity) or referred to being (INSERT ID) on a social networking site?

1 Yes

2 No

All in all, thinking about the important people in your life, how many are aware that you are (INSERT ID)?

1 All or most of them

2 Some of them

3 Only a few of them

4 None of them

Thinking about the people you work with closely at your job, how many of these people are aware that you are (INSERT ID)?

1 All or most of them

2 Some of them

3 Only a few them

4 None of them

How many of your close friends are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender?

1 All or most of them

2 Some of them

3 Only a few of them

4 None of them

Group Consciousness

As a (INSERT ID) (IF INSERTID = 2 AND SEX = 2: woman; IF INSERTID = 2 AND SEX = 1: man; IF INSERTID = 4: person; IF INSERTID = 1: woman), how much do you feel you share common concerns and identity with (RANDOMIZE)

ASK IF INSERT ID = 3,4 OR (INSERT ID = 2 AND SEX = 1, MISSING)

a. Lesbians

ASK IF INSERT ID = 1,3,4 OR (INSERT ID = 2 AND SEX = 2, MISSING)

b. Gay men

ASK IF INSERT ID = 1,2,3

d. Transgender people

RESPONSE CATEGORIES:

1 A lot

2 Some

3 Only a little

4 Not at all

Stigma Index

For each of the following, please indicate whether or not it has happened to you because you are, or were perceived to be (INSERT ID)? (RANDOMIZE ITEMS)

a. Been threatened or physically attacked

b. Been subject to slurs or jokes

c. Received poor service in restaurants, hotels, or other places of business

d. Been made to feel unwelcome at a place of worship or religious organization

e. Been treated unfairly by an employer in hiring, pay, or promotion

f. Been rejected by a friend or family member

RESPONSE OPTIONS

1 Yes, happened in past 12 months

2 Yes, happened, but not in past 12 months

3 Never happened

Rural

MSA status

−2 Not asked

−1 Refused

0 Non-metro

1 Metro

Ideology

In general, would you describe your political views as…

1 Very conservative

2 Conservative

3 Moderate

4 Liberal

5 Very liberal

Partisan

In politics today, do you consider yourself a…?

1 Republican

2 Democrat

3 Independent

4 Something else, please specify (SPECIFY, one line box)

Social Justice Sexuality Project (2010)

Participation Index, LGBT Participation Index, POC Participation Index, LGBT POC Participation Index

Q1a: How often have you attended a racial or ethnic LGBT Pride festival (e.g., Black Pride Latina/o Pride, Asian Pride, etc.)? (Check one box)

1 Never

2

3

4

5

6 Frequently

Instructions Q8a–8f: Thinking about LGBT groups, organizations, and activities in general, during the past 12 months, how often have you: (Check one box per question)

Q8a: Participated in political events (e.g., a march, rally, etc.)

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Q8b: Participated in social or cultural events (e.g., clubs, movies, restaurants, etc.)

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Q8f: Donated money to an organization

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Instructions for Q9a–Q9f: Thinking about groups, organizations, and activities for People of Color, during the past 12 months, how often have you: (Check one box per question)

Q9a: Participated in political events (e.g., a march, rally, etc.)

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Q9b: Participated in social or cultural events (e.g., clubs, movies, restaurants, etc.)

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Q9f: Donated money to an organization

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Instructions for Q10a–10f: Thinking about groups, organizations, and activities for LGBT People of Color, during the past 12 months, how often have you: (Check one box per question)

Q10a: Participated in political events (e.g., a march, rally, etc.)

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Q10b: Participated in social or cultural events (e.g., clubs, movies, restaurants, etc.)

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Q10f: Donated money to an organization

1 Never

2 Once or twice a year

3 About six times a year

4 About once a month

5 About once a week

6 More than once a week

Religiosity

Q11a: I pray daily

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Agree

4 Strongly agree

Q11b: I look to my faith as providing meaning and purpose in my life

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Agree

4 Strongly agree

Q11c: I consider myself active in my faith or religious institution

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Agree

4 Strongly agree

Q11d: I enjoy being around others who share my faith

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Agree

4 Strongly agree

Q11e: My faith impacts many of my decisions

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Agree

4 Strongly agree

Q12d: How often do you attend religious services?

1 Never

2 Less than once a year

3 Once or twice a year

4 Several times per year

5 About once per month

6 2–3 times per month

7 Nearly every week

8 Every week

Denomination

Q12b: What religion do you currently practice?

1 Catholic

2 Protestant

3 Jewish

4 Muslim or Islamic

5 Atheist

6 Agnostic

7 None

8 Other

Conflict

Q12c: Thinking about your sexual identity, how much has your religious tradition or spiritual practice been a negative or positive influence for you in coming to terms with your LGBT identity?

1 Negative influence

2

3

4 Neither negative nor positive

5

6

7 Positive influence

Outness Index

Instructions—How many people within the following communities are you “out” to?

Q14a: Family

1 None

2 Some

3 About half

4 Most

5 All

Q14b: Friends

1 None

2 Some

3 About half

4 Most

5 All

Q14c: Religious community

1 None

2 Some

3 About half

4 Most

5 All

Q14d: Co-workers

1 None

2 Some

3 About half

4 Most

5 All

Q14e: People in your neighborhood

1 None

2 Some

3 About half

4 Most

5 All

Q14f: People online (e.g., Myspace, Facebook, etc.)

1 None

2 Some

3 About half

4 Most

5 All

Shared Concern

Q6a: I feel connected to my local LGBT community

1 Strongly disagree

2

3

4

5

6 Strongly agree

Q6b: I feel that the problems faced by the LGBT community are also my problems

1 Strongly disagree

2

3

4

5

6 Strongly agree

Q6c: I feel a bond with other LGBT people

1 Strongly disagree

2

3

4

5

6 Strongly agree

Q13: Do you feel that your sexual orientation is an important part of your identity?

1 Not important at all

2

3

4

5

6 Extremely important

Stigma Index

Q5a: Homophobia is a problem within my racial or ethnic community

1 Strongly disagree

2

3

4

5

6 Strongly agree

Q5b: Homophobia is a problem within my neighborhood

1 Strongly disagree

2

3

4

5

6 Strongly agree

Q5c: In general, homophobia is a problem within all communities of color

1 Strongly disagree

2

3

4

5

6 Strongly agree

Sex

Instructions—What is your current gender identity?

Q18a2: Female

0 No

1 Yes

Race

Instructions—Which of the following racial groups come closest to identifying you?

Q19: Black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, White

0 No

1 Yes

Income