The 2012 contest between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney included fierce dialogue about women and issues typically connected to them. The inflammatory comments that conservative radio-show host Rush LimbaughFootnote 1 made about female law student Sandra Fluke and the Affordable Health Care Act's (ACA) requirements that all workplaces cover contraceptives were central topics in the news.Footnote 2 The controversy literally followed Romney in the form of “Pillamina,” a human-sized costume designed to look like a pack of birth control pills that shadowed the candidate's summer swing state tour. While “Pillamina” was the work of Planned Parenthood's Action Fund, the Obama campaign also took aim at Romney on this issue, running a television commercial featuring “Dawn and Alex,” two women talking about how out of touch Romney is with women's health issues. The Romney campaign's attempts to counter these attacks and shift the focus of conversation were largely thwarted, as questionable comments from Republican Senate candidates Todd AkinFootnote 3 and Richard MourdockFootnote 4 brought the issue of abortion to the forefront. Both of these statements added fuel to the narrative that Republicans are out of touch with women's needs. And Romney himself contributed to the problem, as his notorious “binders full of women” debate responseFootnote 5 broadened the scope of the issue from reproductive rights to more general issues about gender equality. Altogether, these Republican comments and positions opened the door for Democrats on the campaign trail to attack the party, and a popular conclusion is that this “War on Women” narrative hurt the Republican Party and played an integral part in Obama's victory.

The scholarly work of Deckman and McTague (Reference Deckman and McTague2015) largely echoes this sentiment, as the authors conclude that “the gender gap grew from a difference of 7 percentage points between Obama and McCain in 2008 to a difference in 10 percentage points between Obama and Romney in 2012, and insurance coverage for birth control appears to have been a decisive factor for many voters, especially women” (19). The implication of this statement and of much of the media coverage is that the gender gap grew because women were increasingly drawn to the Democratic Party. And yet, Sides and Vavrek (Reference Sides and Vavrek2013) find that “despite the Obama campaign's claim that women's health was an advantageous issue for them, news coverage of the controversies about contraception and abortion did not appear to change women's vote intentions or views of the candidates” (197). Aggregate vote returns also do not support such an assumption. Obama did win the female vote in 2012, but a comparison of these results back to those from 2008Footnote 6 shows that women were actually no less likely to vote Republican (56% to 43% in favor of Obama in 2008 and 55% to 44% in favor of Obama in 2012). Rather, the larger gender gap in 2012 appears to be driven by the fact that Obama's share of the male vote decreased from 49% in 2008 to 45% in 2012. With these results in mind, we shift focus and explore why men continue to favor the Republican Party and whether the “War on Women” may have played a part in deepening the divide.

That is, persistent differences in opinions (e.g., Burns and Gallagher Reference Burns and Gallagher2010; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002) mean that for every appeal to women voters, there is the possibility of fallout among men. Indeed, some argue that men's migration to the Republican Party is related to Democrats’ association with feminism and women's organizations (e.g., Edsall and Edsall Reference Edsall and Edsall1991), and feminist identification has been highlighted as a factor driving the gender gap in the 1980s and 1990s (e.g., Conover Reference Conover1988; Cook and Wilcox Reference Cook and Wilcox1991; Klein Reference Klein1984; Manza and Brooks Reference Manza and Brooks1998). Building on these works, we investigate the possibility that there may be another factor dividing men and women that heretofore has been largely ignored: modern sexism, or “the denial of continued discrimination, antagonism toward women's demands, and lack of support for policies designed to help women” (Swim et al. Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995).

Using data from the 2012 American National Election Study (ANES), we present analyses that show that a denial of gender discrimination problems creates significant divisions both among men and between men and women. In addition, we also show analyses suggesting that these effects are greatest among liberal and moderate men. The resulting implication is that modern sexism is contributing to the partisan gender gap, as even men whose ideology is more in line with that of the Democratic Party are more likely to support the Republican candidate if they do not see issues of gender equity as a real problem. These findings not only make an important contribution to the gender gap literature, but they also highlight the need for more careful and nuanced examinations of the effects of gender-related messages in campaigns.

INCORPORATING MODERN SEXISM

The extant literature has long shown that it has been a shift in male preferences, rather than a shift in female preferences, that has created the gender gap (Bendyna and Lake Reference Bendyna, Lake, Adell Cook, Thomas and Wilcox1994; Box-Steffensmeier, DeBoef, Lin Reference Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef and Lin1997; Kaufmann Reference Kauffman2006; Kaufmann and Petrocik Reference Kauffman and Petrocik1999; Wirls Reference Wirls1986). The large body of work exploring these differences broadly attributes them to both socialization (Diekman and Schneider Reference Diekman and Schneider2010; Gilligan Reference Gilligan1982; Ruddick Reference Ruddick and Trebilcot1983; Skok Reference Skok1989) and issue preferences (Alvarez, Chaney, and Nagler Reference Chaney, Michael Alvarez and Nagler1998; Bendyna and Lake Reference Bendyna, Lake, Adell Cook, Thomas and Wilcox1994; Conover Reference Conover1988; Cook and Wilcox Reference Cook and Wilcox1991; Gilens Reference Gilens1988; Klein 1986; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1985; May and Stephenson Reference May and Stephenson1994; Piven Reference Piven and Rossi1985; Welch and Hibbing Reference Welch and Hibbing1992). Differences in opinions on the role of government in providing benefits, in particular, have garnered a substantial amount of scholarly attention. Piven (Reference Piven and Rossi1985), for example, finds that women have been more likely to continue to support Democratic positions on welfare and other similar policies because they identify with feelings of economic insecurity more than their male counterparts. More recently, both May and Stephenson (Reference May and Stephenson1994) and Box-Steffensmeir, DeBoef, and Lin (Reference Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef and Lin1997) produce similar findings. These works show that large subsections of women have shifted from a dependence on a male provider, to a state-provider and that, in general, “as conservatism flows, women, more than men, have developed a stronger propensity to identify or remain identified with the Democratic Party as the champion of the welfare state” (Box-Steffensmeir, DeBoef, and Lin Reference Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef and Lin1997, 15).

According to Deckman and McTague (Reference Deckman and McTague2015), it is these differences in views on the role of government that colored reactions to the “War on Women” in 2012. But in doing so, they, like Sides and Vavrek (Reference Sides and Vavrek2013), focus on only two aspects of the campaign dialogue: access to contraception and abortion. Noted above, as the 2012 campaign progressed, dialogue shifted from being focused only on these two issues to more general discussions of women's equality. As such, we draw on a smaller subset of the gender gap literature that focuses on feminist identification (e.g., Conover Reference Conover1988; Cook and Wilcox Reference Cook and Wilcox1991; Klein Reference Klein1984; Manza and Brooks Reference Manza and Brooks1998) and explore the possibility that it is broader attitudes about gender that also contribute to the differences between male and female voting patterns.

More specifically, we attempt to better disentangle the various components of feminist identificationFootnote 7 and isolate the effects of feelings about gender equity and perceived discrimination. While opinions on all gender-related matters are undoubtedly correlated, we do so because the public opinion literature highlights important differences between those policies that relate to role equity and those that relate to role change. This distinction is not always easy or clear (e.g., Carden Reference Carden1977; Gelb and Palley Reference Gelb and Palley1982; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002), but we draw on the framework advanced by Burns and Gallagher (Reference Burns and Gallagher2010):

Abortion and women in combat are examples of today's role-change issues because opinions on these issues are based largely on predispositions about women's place. By contrast, equity issues are issues like equal pay and laws to protect women against job discrimination—individuals considering these issues bring to bear ideas about structural critiques and, when possible, interdependence (431).

Burns and Gallagher (Reference Burns and Gallagher2010) go on to argue that when looking at the public opinion literature through the lens of this framework, it appears that when there is a gender gap, it more often exists when equity, not roles, is the focus. And thus, we advance the literature by expanding the approach of previous works and better accounting for the differences in individuals’ opinions about gender discrimination.

These opinions can be captured by what Swim et al. (Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995) term “modern sexism.” In contrast to traditional sexism, which is the open endorsement of a subordinate role of females, or traditional sexism (e.g., Becker and Swim Reference Becker and Swim2012; Sibley, Overall, and Duckitt Reference Sibley, Overall and Duckitt2007), modern sexism is a “uniquely contemporary” form of sexism (Glick et al. Reference Glick, Fiske, Mladinic, Saiz, Abrams, Masser and Lopez2000) that is a response to the changing role of women in society and the increase in the demand for gender equality. Like modern racism (Sears Reference Sears, Katz and Taylor1988), modern sexism captures unfavorable attitudes toward women that are conveyed in a way that could be interpreted as nonprejudiced (Swim and Cohen Reference Swim and Cohen1997). That is, whereas traditional sexism is characterized by a support for differential treatment of women and men, the application of double standards in the judgement of men's and women's behaviors, and a belief that women are less suited for certain tasks, modern sexism is typified by a resentment of complaints or special favors and perhaps most importantly here, a denial of the existence of discrimination against women (Swim and Cohen Reference Swim and Cohen1997). Modern sexism is more subtle; it does not require open hostility or disrespect for women and often is masked as egalitarianism, chivalry, or affection (Becker and Swim Reference Becker and Swim2011). Yet it is still sexism in that it “provides a rationale against government intervention into social problems by normalizing inequality between men and women” (Cassese, Barnes, and Branton Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015, 7; see also Jost, Wakslak, and Tyler Reference Jost, Wakslak, Tyler, Hegtvedt and Clay-Warner2008).

To better illustrate the differences between these two concepts, consider the example of two individuals who both oppose the implementation of an affirmative action program in corporate promotions. Person A opposes it because she believes that women are less qualified to hold executive positions, while Person B opposes it because she does not think that women actually face any barriers in the workplace. Though both individuals support a status quo that perpetuates gender inequality, only Person A would be labeled a sexist in the traditional sense. Thus, modern sexism is distinct in that it identifies a subset of individuals who, like Person B, are not openly prejudiced, but whose attitudes still contribute to systemic discrimination.

Despite the impressive evidence of the existence of modern sexism, there are very few explicit investigations of how it impacts political behavior. Swim et al. (Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995) find that modern sexism is a significant predictor of preference for a male versus a female Senate candidate, but that these significant effects disappear once partisanship and ideology are controlled. Similarly, both Dwyer et al. (Reference Dwyer, Stevens, Sullivan and Allen2009) and Tate (Reference Tate2014) fail to find significant effects of modern sexism in the 2008 election. Cassese, Barnes, and Branton (Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015), however, do find significant effects. They show that modern sexism depresses support for pay equity among men of all ideological leanings and among moderate and conservative women. Likewise, McThomas and Tesler (Reference McThomas and Tesler2016) find significant effects of modern sexism on the favorability ratings of a variety of political figures. Most notably, they find the strongest effects on ratings of Hillary Clinton, who defied traditional gender roles as secretary of state. Despite these mixed results, we expect that prominence of the “War on Women” rhetoric in the 2012 campaign should have created an environment wherein modern sexism yields significant effects on vote choice. Specifically, we expect that modern sexism will predict male support for Romney.

Our reason for expecting to find this effect among men but not women is not that women cannot be sexist. Although men do exhibit higher levels of modern sexism, there still is significant variation within both genders. Modern sexism generally also involves stereotyping women as more sensitive, compassionate, or fragile—stereotypes that many females see as complimentary or favorable (e.g., Eagly and Mladinic Reference Eagly and Mladinic1989; Kilianski and Rudman Reference Kilianski and Rudman1998). This, combined with a desire for security (Sibley, Overall, and Duckitt Reference Sibley, Overall and Duckitt2007) in turn leads some women to approve of, agree with, and even perpetuate modern sexism (e.g., Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske2001). And to be sure, Cassese, Barnes, and Branton (Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015) actually find that the strongest substantive effects of modern sexism on support for pay equality are among conservative women.

Rather, our expectation is based on two major lines of reasoning. First, women tend to view gender inequality as a personal problem rather than one that requires political action (Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002; Sigel Reference Sigel1996). For example, a 2014 public opinion poll showed that although 61% of women see men as having more opportunities in the workplace, 42% cited women's choices as a major reason for pay disparities and only 38% supported the government enacting more laws to address discrimination.Footnote 8 This is not dissimilar from Welch and Hibbing's (Reference Welch and Hibbing1992) argument that women utilize sociotropic versus pocketbook economic evaluations because they have a greater tendency to blame themselves rather than others when things go wrong and is also consistent with psychological studies showing a norm of internality and a preference for individuals who take personal responsibility for outcomes (e.g., Beauvois and Dubois Reference Beauvois and Dubois1988; Dubois and Beauvois Reference Dubois and Beauvois1996). Consequently, we expect that women's opinions on gender equality may not directly affect their vote choices.

Second, there is a greater potential for backlash and alienation among men in general but most specifically among male sexists. Public opinion data from October 2012 show that while women considered abortion and equal rights as two of the most important issues of the election, men instead prioritized economic issues.Footnote 9 And among men, modern sexists may have been particularly put off by the prominent discussion of women's issues. That is, male sexists may have felt that the Democratic Party was too focused on issues that, in their minds, were not even problems. The Republican Party's traditional association with economic issues and the emphasis of the Romney campaign,Footnote 10 on the other hand, may have appeared to be more in touch with their priorities.

Moreover, a second key facet of modern sexism – resentment of programs intended to address gender inequality—may also be particularly strong among men. Even if sexist women oppose certain policies, they still, because of their gender, stand to benefit from them or at minimum, be no worse off. But sexist men may perceive more to lose. A number of studies evidence the tendency of men, but not women, to view gender equality as a zero-sum game (Bosson et al. Reference Bosson, Vandello, Michniewicz and Guy Lenes2012; Kehn and Ruthig Reference Kehn and Ruthig2013; Wilkins et al. Reference Wilkins, Wellman, Babbitt, Toosi and Schad2015). That is, a male sexist may see pay raises for women or policies geared toward increasing female enrollments in certain academic programs as coming at the expense of their own salaries or their own positions in those programs.

Female sexists, on the other hand, would not be as inclined toward expecting negative repercussions and subsequently, their opinions about or resentment toward these types of policies should have less of an effect on their vote choice. This line of thinking is seemingly supported by the experimental work of Anderson, Lewis, and Baird (Reference Anderson, Lewis and Baird2011; cf. Schaffner Reference Schaffner2005), who show that a candidate supporting harsher punishments for sexual harassment was not rewarded by women, but was significantly penalized by men. Though the authors do not link this finding to modern sexism, it fits with our logic in that men would disproportionately be the recipients of these harsher punishments. As such, we think that the greater stakes for males will lead modern sexism to create an additional cleavage.

ANALYSES

Data and Measures

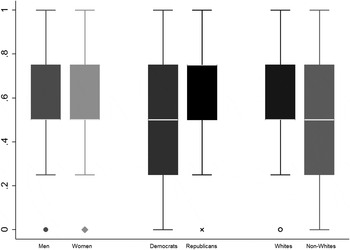

We analyze data from the 2012 ANES.Footnote 11 In representing modern sexism, we follow Cassese, Barnes, and Branton (Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015) and focus on the denial of the existence of discrimination against women. Our measure is a five-category variable constructed from responses to the question,Footnote 12 “How serious a problem is discrimination against women in the United States?” and is recoded to range from 0 (“a very serious problem”) to 1 (“not a problem at all”). We choose to utilize this particular question because Yoder and McDonald (Reference Yoder and McDonald1997) show that this is a distinct component of the concept and is free from correlations with possibly confounding factors like age, education, and race. Moreover, similar questions were asked about blacks and Hispanics, allowing us to construct a comparable measure of racism that can help address concerns about intersectionality. Figure 1 shows the distribution of this key variable for several types of respondents in our sample.

Figure 1. Distributions of the modern sexism variable.

Though the mean values of modern sexism for male (

![]() $\bar X$

= .59), Republican (

$\bar X$

= .59), Republican (

![]() $\bar X$

= .66), and white (

$\bar X$

= .66), and white (

![]() $\bar X$

= .60) respondents are all higher than those for female (

$\bar X$

= .60) respondents are all higher than those for female (

![]() $\bar X$

= .53), Democratic (

$\bar X$

= .53), Democratic (

![]() $\bar X$

= .50), and non-white (

$\bar X$

= .50), and non-white (

![]() $\bar X$

= .50) respondents, there is significant variation across gender, party identification, and race. Given the coding of this variable and the stances of the two parties, we expect the estimated coefficient to be positive, indicating that support for Romney should increase with Modern Sexism.

$\bar X$

= .50) respondents, there is significant variation across gender, party identification, and race. Given the coding of this variable and the stances of the two parties, we expect the estimated coefficient to be positive, indicating that support for Romney should increase with Modern Sexism.

We use this variable in a vote choice model where the dependent variable is coded 1 if the respondent reported voting for Romney and 0 if the respondent reported voting for Obama.Footnote 13 Along with basic political and demographic variables, we include several variables that are particularly relevant to the study of gender and voting. First, we include two variables related to the two most prominent “women's” issues of the election: abortion and the coverage offered under the ACA. Abortion is a four-category variable ranging from 0 (“by law, a woman should always be able to obtain an abortion as a matter of personal choice”) to 1 (“by law, abortion should never be permitted”). Healthcare is a seven-category variable ranging from 0 (the respondent favors the ACA a great deal) to 1 (the respondent opposes the ACA a great deal). This does not specifically ask about the birth control mandate, but given findings that feelings about the mandate are more about the size and scope of government rather than culture (Deckman and McTague Reference Deckman and McTague2015), we expect that this more general question may still tap a similar underlying dimension.

Second, we include two variables related to the role of government, as issues related to this have been shown to be large drivers of the divide between men and women (e.g., Kaufman and Petrocik Reference Kauffman and Petrocik1999). Government Services is a seven-category variable ranging from 0 (“government should provide many more services”) to 1 (“government should provide many fewer services”). Taxes takes on one of three values, reflecting whether the respondent favors (coded 0), opposes (coded 1), or neither favors nor opposes (coded .5) reducing the deficit by raising personal income taxes on those making more than $250,000. Lastly, we account for the importance of evaluations of the national economy (e.g., Chaney, Alvarez, and Nagler Reference Chaney, Michael Alvarez and Nagler1998; Kam Reference Kam2009; Welch and Hibbing Reference Welch and Hibbing1992) and include the variable Sociotropic Economics. This is a five-category variable reflecting respondents’ opinions of the U.S. economy, not their own personal financial situation, and ranges from 0 (those thinking the economy is much better) to 1 (those thinking the economy is much worse).

Results

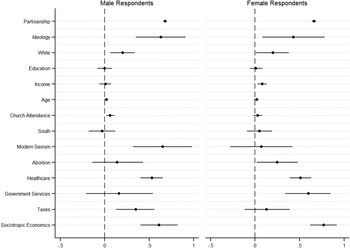

To test for significant differences between men and women, we run a logistic regression model that interacts each of our covariates with a dichotomous gender variable. Figure 2 plots the marginal effects derived from this model.Footnote 14

Figure 2. Factors predicting vote for Romney.

The plots in Figure 2 reveal many similarities between men and women. Partisanship, ideology, race, opinions on the ACA, and sociotropic economic evaluations all had significant effects, regardless of gender. Yet there are also some gender differences. Opinions on taxes are significant for men, but not women. Similarly, opinions on abortion and government services are significant for women but not men. However, none of the interactions between these factors and the gender variable are significant, indicating that we cannot be confident that men and women really did utilize these factors differently when choosing between Romney and Obama. The only significant interaction term in our model is the interaction between Female and Modern Sexism (p = .01). As Figure 2 shows, among men, a shift from viewing discrimination against women as “a very serious problem” to seeing it as “not a problem at all” increases the probability of voting for Romney by about .65. Among women, on the other hand, there is no significant change. This is not to say that matters of gender equity are not important to women. Rather, we suspect that this lack of direct effects may be due to either women not seeing discrimination as a political matter or to women incorporating their opinions on gender equity into other concerns. But whatever the reason, the fact remains that our inclusion of modern sexism revealed an important way that the voting behavior of men and women differ.

To check the robustness of these findings, we present two models—one for each gender—that include additional controls. The variable Traditional Sexism reflects a respondent's opinions about whether it is better if the man works and the woman takes care of the home. This is a seven-category variable that ranges from 0 (much worse) to 1 (much better). The variable Feminism ranges from 0 to 1 and is constructed from respondents’ feeling thermometer ratings of feminists.Footnote 15 The two are only weakly correlated with our measure of modern sexism (r = .09 for traditional sexism and r = −.29 for feminism) and each other (r = −.14). As such, we include them as independent concepts to aid our argument that the effects we find are due to specific feelings about gender discrimination and not more overt sexism or broader feelings about women and the women's movement.

Our measure of racism utilizes two questions that are very similar to the one used to construct our modern sexism measure. These questions asked respondents about the current level of discrimination against Blacks and Hispanics, offering five choices ranging from “a great deal” to “none at all.” The mean of the respondent's two answers is used to construct the variable Racism (Crohnbach's α = .82), which ranges from 0 to 1 and has a mean of .55. As Cassese, Branton, and Barnes (Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015) and the broader literature on intersectionality show (e.g., Cole Reference Cole2009; King Reference King1988; Simien, and Hancock Reference Simien and Hancock2011), gender and racial discrimination have joint influences and that “exploring gender independently of race has the effect of looking past the ways that racism and sexism mutually reinforce one another to form an interlocking system of oppression” (4; see also Collins Reference Collins2000). Indeed, our measures of modern sexism and racism are correlated (r = .39), and so what we are attributing to the former may actually be due to the latter.Footnote 16 The results are displayed in the leftmost columns (Models 1M and 1F) of Table 1.

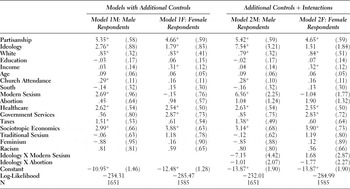

Table 1. Vote for Romney by gender

Note: Cell entries are logistic regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. All political variables are recoded to range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more Republican/conservative positions. * = p < .05.

Looking first at just female respondents (1F), we see one notable difference from the results presented in Figure 2. Once we include the additional controls, abortion attitudes no longer have a significant effect. This suggests that if the discussion of abortion had an effect, it operated through other concerns. Turning to the model focused solely on male respondents (1M), however, we see that the results largely stay the same. Modern sexism still exerts a significant, positive effect on the likelihood of voting for Romney.

But do these effects contribute to the observed gender gap? About 46% of male voters are in the two highest categories of modern sexism and are significantly more likely than their female counterparts to vote Republican. These aggregate figures are thus suggestive that modern sexism may contribute to men's movement away from the Democratic Party. To be sure, liberals and moderates comprise about 34% of male voters in the two highest categories of sexism.

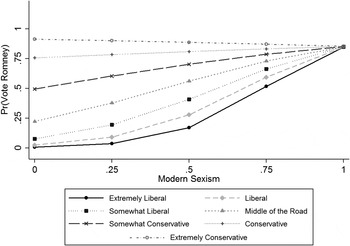

To probe this further, Model 2M of Table 1 includes interactions between Ideology and both Modern Sexism and Abortion. If higher levels of sexism increase Republican support among liberals more than lower levels decrease it among conservatives, then this would suggest the type of alienating effects that motivated our expectation that there would be greater effects among men. Though the interaction term is not significant, the marginal effects of modern sexism are significant (p < .05) for the four most liberal categories and the predicted probabilities in Figure 3 show that the substantive effects of sexism are contingent on ideology.

Figure 3. Male vote for Romney by ideology and modern sexism.

Modern sexism only significantly impacts the vote choice of those with liberal or moderate self-identifications. As modern sexism increases, the differences between men with different ideological predispositions disappear. Additional analyses that were run but not shown indicate that these results hold regardless of race.Footnote 17 It appears, then, that while modern sexism among men predisposed (due to their ideology) to support Obama helped the Republican Party, there were no offsetting gains for Democrats among men who were low on this sexism measure.

In addition, there were also no offsetting gains among conservatives with more liberal abortion attitudes. The interaction between ideology and abortion is not significant for either men or women (Model 2F in Table 1). Moreover, both terms are negative, indicating that even if there were significant effects, the effects would be concentrated among liberals. So while modern sexism may have aided Republicans among men predisposed to support Obama, the issue of abortion did not appear to help Democrats among either men or women predisposed to vote for Romney. These findings are consistent with Sides and Vavrek's (Reference Sides and Vavrek2013) claim that the salience of abortion had very little effect on the 2012 election and support arguments that explaining the gender gap requires an examination of the variation among men. Given the limitations of this cross-sectional observational data, it is impossible to directly link these findings to the rhetoric of the 2012 campaign, but overall, the results presented in this section repeatedly show a strong effect of men's opinions about gender discrimination and are consistent with the proposition that the “War on Women” may have widened the gender gap not by attracting more women to the Democratic Party, but by alienating sexist men from it.

DISCUSSION

In the wake of the 2012 presidential election, much of the popular and scholarly focus was on female voters and the impact of abortion and contraception. We push beyond this approach and incorporate broader opinions on gender equity. In doing so, we expose another key way that male and female voters differ, as we show that modern sexism as represented by feelings about discrimination against women creates a significant divide. In fact, our analyses show that this is the only factor that significantly separates men and women. These findings complement the “men-left” narrative (e.g., Bendyna and Lake Reference Bendyna, Lake, Adell Cook, Thomas and Wilcox1994; Box-Steffensmeier, DeBoef, and Lin Reference Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef and Lin1997; Kaufmann Reference Kauffman2006; Kaufmann and Petrocik Reference Kauffman and Petrocik1999; Wirls Reference Wirls1986), and because we are, to the best of our knowledge, one of the first to explicitly incorporate modern sexism, we enhance this general line of work by better identifying which men may indeed be driving this gap.

Further exploring the role of modern sexism in evaluations of female candidates is also an important task for future research, especially in light of Hillary Clinton's historic candidacy. Regardless of the issues that emerge, examinations of the presence of a female candidate lead to media stereotyping (e.g., Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009; Meeks Reference Meeks2013; Uscinski and Goren Reference Uscinski and Goren2011) and can make sexism headline news.Footnote 18 This type of discourse may further exacerbate the divisions among men and the divide between women and men. But again, modern sexism is not a purely male phenomenon, and thus, a female candidacy may reveal effects among women that were absent in 2012's all-male contest.

While we cannot isolate campaign effects, it appears that some men predisposed to favor the Democratic Party may have been put off by the 2012 campaign narrative on women's issues. And as such, our work has interesting implications for the study of campaign messaging. We are by no means suggesting that continuing a “War on Women” would be an effective strategy for Republicans. We agree with Mendelberg (Reference Mendelberg2001), and whereas there may be an incentive to activate latent racism, there is no similar incentive to activate sexism, especially given that women make up a majority of voters. Yet the fact remains that modern sexism does exist among both men and women in the U.S. and thus, even if unintentional, campaigns and the strategies they pursue may trigger these predispositions. For every appeal to women voters, there is the possibility of fallout among men and women who would rather see other issues prioritized, who do not see these issues as problems, or who are resentful of the attention they garner. As such, further exploration of what types of appeals are most likely to activate modern sexism and among whom these effects are the strongest will offer a more complete picture of the complex way that gender and gender issues influence political outcomes.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X17000083.