INTRODUCTION

It is widely accepted globally that establishing, developing, and maintaining quality relationships with customers is important when conducting business, especially in complex and highly competitive markets (Ndubisi & Wah, Reference Ndubisi and Wah2005; Weir, Sultan, & Van De Bunt, Reference Weir, Sultan, Van De Bunt and Ramady2016). However, the way these relationships are nurtured and deepened varies in different cultures, with notable differences between the East and West (Fainshmidt, Judge, Aguilera, & Smith, Reference Fainshmidt, Judge, Aguilera and Smith2018; Flambard-Ruaud, Reference Flambard-Ruaud2005; Kabasakal & Bodur, Reference Kabasakal and Bodur2002; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Sultan, Van De Bunt and Ramady2016; Yen, Yu, & Barnes Reference Yen, Yu and Barnes2007). Challenging the dominant Anglo-Western-centric model is seen as essential, not least because it perpetuates the false belief in universality that remains prevalent in many areas of service research, particularly in tourism and hospitality (Tucker & Zhang, Reference Tucker and Zhang2016: 250). In an era of transforming economies and rapidly expanding markets, context-specific research becomes even more important, along with the need for Eastern knowledge and theory to be explored through the prism of different cultures (Chambers & Buzinde, Reference Chambers and Buzinde2015). Some studies have begun the important task of uncoupling service research from Western epistemologies by focusing on guanxi-type relationships (Tucker & Zhang, Reference Tucker and Zhang2016: 250). Guanxi, a Chinese construct characterized by relationship-based networks, has been used by scholars to contextualize their discussions of relationship development in China (Luo, Huang, & Wang, Reference Luo, Huang and Wang2012). Many features of guanxi are not unique to Chinese society, but are present to some degree in every society in the world, including the Middle East (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Sultan, Van De Bunt and Ramady2016). The similarities between network-based relationships in China and those in the Arab world prompted Hutchings and Weir (Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b) to call for research addressing networks in the Arab world generally and guanxi-type relationships specifically, given the lack of adequate research. Answering this call, Shaalan, Weir, Reast, Johnson, and Tourky (Reference Shaalan, Weir, Reast, Johnson and Tourky2014) found that similar relationships to those found in Chinese guanxi existed in the Middle East, and agreed with Weir and Hutchings (Reference Weir and Hutchings2005) that life in the Arab world was wholly reliant on networks of interpersonal connections. The overlapping features between Chinese and Middle Eastern networks include the benefits for business and indeed the need to use guanxi-type relationships to achieve business success (Shaalan et al., Reference Shaalan, Weir, Reast, Johnson and Tourky2014). Accordingly, this study uses the term ‘guanxi-type relationships’ to refer to the networks of interpersonal ties found in the Middle East.

Despite the work already undertaken to understand the role of guanxi-type relationships, significant gaps in knowledge can be clearly identified. Firstly, exploration of the role of such relationships in cultures outside China has been limited, especially in non-Western cultures such as the Middle East. Secondly, the role of guanxi-type relationships in the specific context of the hotel sector has not been explored although the hotel sector is a relationship-intensive industry. Thirdly, there is a lack of studies on the interplay between guanxi-type relationships and relationship marketing, especially in the hotel and tourism context, where it could be highly significant given the potential effects on guest satisfaction and retention. Our extensive review and critical discussion of the extant literature provide a solid theoretical foundation and rationale for our study, since previous studies, while rich in detail, are not without gaps and problems. Firstly, the role of guanxi-type relationships in cultures outside China has attracted little attention, with only a few studies focusing on the West (e.g., Burt, Reference Burt2019; Burt, Bian, & Opper, Reference Burt, Bian and Opper2018), the Middle East (Berger, Herstein, McCarthy, & Puffer, Reference Berger, Herstein, McCarthy and Puffer2019; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b), or other developing states grounded in unique political, cultural, social, and economic settings. Li, Zhou, Zhou, and Yang (Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019) support this view, arguing that further research on guanxi is needed not only in China but also in the emerging global context. The lack of studies on the Middle East has persisted despite substantial evidence of its unique business and cultural practices (Sharma, Reference Sharma2010). Middle Eastern culture has high collectivistic values and strong long-term orientation (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001), making it culturally very distinct from the West. Furthermore, an extensive review by Samaha, Beck, and Palmatier (Reference Samaha, Beck and Palmatier2014) of relationship marketing studies from 36 countries revealed great differences in the effects of relational mediators such as trust and customer satisfaction in different countries, contexts, and cultures.

Overall, inadequate attention has been paid to better understanding guanxi-type networks and how they influence business in the Middle Eastern context (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b). Berger and Herstein (Reference Berger and Herstein2012) argue that a clearer understanding of the components and operation of guanxi-like relationships in the business world is essential in order to grasp its central importance in a culture where the first rule of business is socialization. Some scholars have specifically encouraged further research on guanxi-type relationships in the Middle East. For example, Weir et al. (Reference Weir, Sultan, Van De Bunt and Ramady2016) argue that, given the central importance of interpersonal relationships in collectivist cultures, their role in the development of relationship strategies should be explored.

Secondly, alongside this shortage of guanxi-based research in the culturally-distinct geographical context of the Middle East, there is a general lack of such studies in the specific context of the hotel sector despite its importance. Previous studies have focused on a range of fields such as marketing (Lee, Tang, Yip, & Sharma, Reference Lee, Tang, Yip and Sharma2017; Shaalan, Reast, Johnson, & Tourky, Reference Shaalan, Reast, Johnson and Tourky2013), supply chain management (Geng, Mansouri, Aktas, & Yen, Reference Geng, Mansouri, Aktas and Yen2017), organizational learning (Chung, Yang, & Huang, Reference Chung, Yang and Huang2015; Leung, Chan, Chung, & Ngai, Reference Leung, Chan, Chung and Ngai2011), operation management (Wu & Chiu, Reference Wu and Chiu2016), entrepreneurship (Chen, Chang, & Lee, Reference Chen, Chang and Lee2015; Phan, Zhou, & Abrahamson, Reference Phan, Zhou and Abrahamson2010), human resources management (Ren & Chadee, Reference Ren and Chadee2017), and strategic management (Cao, Baker, & Schniederjans, Reference Cao, Baker and Schniederjans2014). However, little is known about the role and impact of guanxi-type relationships in different cultures in the hotel industry. The few exceptions include Chen (Reference Chen2017), who contributed a contextual interpretation of guanxi, but only in the context of the development of Chinese tourism.

Thirdly, the interplay between guanxi-type relationships and relationship marketing remains under-researched, especially in the hotel and tourism context. The extent to which guanxi-type relationships could complement relationship marketing has not been fully understood, and no model has empirically integrated guanxi theory into the existing relationship marketing framework, even though many scholars have suggested the importance of this link (Björkman & Kock, Reference Björkman and Kock1995; Geddie, DeFranco, & Geddie, Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2002, Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2005; Shaalan et al., Reference Shaalan, Reast, Johnson and Tourky2013). While the two phenomena are fundamentally different, a detailed understanding of the relationship between them is highly relevant to achieving specific business objectives. Some past research has shown that guanxi-type relationships can be considered an important strategic asset (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Tang, Yip and Sharma2017), while other studies have noted that the personal relationship between a potential customer and a firm's representative (employee or loyal customer) typically develops before a transaction occurs (Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin & Alan, Reference Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin and Alan2000). Some previous theoretical attempts have been made to compare and link guanxi-type relationships and relationship marketing (e.g., Geddie et al., Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2002; Shaalan et al., Reference Shaalan, Reast, Johnson and Tourky2013), but the exact nature of their dimensions and relationship remains unclear. This lack of knowledge has particular relevance in the hotel industry and other parts of the tourism and hospitality sector, given the potential impact on guest satisfaction and retention.

This study answers these calls for specific research in the Middle East, as well as filling the other gaps in the literature highlighted above. Overall, it seeks to advance understanding of guanxi as a holistic and global construct. This article addresses all these gaps in knowledge by exploring the role that guanxi-type relationships play in a non-Western context, focusing specifically on hotel guests in the Middle East who were introduced through interpersonal networks. This unique research population enables us to understand the role of guanxi-type relationships in attracting new guests, and the effect on customer satisfaction and retention. Importantly, we go beyond this to investigate how guanxi-type relationships fit into the existing framework of the relationship marketing framework in the Middle Eastern context, and to explore whether guanxi-type relationships can be transformed into organizational relationships, which in turn generate customer satisfaction and/or retention. To achieve these objectives, we develop and test a conceptual model using inputs from many well-established but diverse viewpoints. To our knowledge, this is the first study to seek to build a unified model integrating guanxi-type relationships into the relationship marketing framework.

In the following sections, we present the theoretical background of the main constructs, elaborate on research gaps, and introduce the proposed research model and hypotheses. The methods are then explained, followed by the presentation of the results of the data analysis and a discussion of the main findings. Finally, implications, limitations, and avenues for future research are presented in the conclusion.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Theoretical Foundations of Guanxi

Establishing strong relationships with customers is regarded as key to business success in today's complex and highly competitive markets. One of the approaches used to achieve this is guanxi, a Chinese term denoting interpersonal networks that have considerable significance in most facets of relationships (Jia, You, & Du, Reference Jia, You and Du2012). While guanxi is not sufficient by itself to persuade customers to buy products (Tsang, Reference Tsang1998), it is a significant foundational element to business relationships, whose main aim is to retain customers (Tseng, Reference Tseng2007). It has been described as a ‘Chinese cultural phenomenon’ (Fan, Reference Fan2002: 374) whose multiple meanings go beyond the closest English equivalents of ‘relationship’ or ‘connection’ (Huang, Reference Huang2008: 468). For example, it can be used to refer to the relationship between people with shared characteristics, active and repeated contact between people, and infrequent, direct communication with a person (Bian, Reference Bian1994: 974). Three distinguishing qualities have been observed: familiarity or intimacy, trust, and mutual obligation (Bian, Reference Bian1997; Burt et al., Reference Burt, Bian and Opper2018; Burt & Burzynska, Reference Burt and Burzynska2017; Burt & Opper, Reference Burt and Opper2017; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019).

Guanxi has been conceptualized in a number of ways in the literature, firstly as a relationship. For example, Alston (Reference Alston1989: 28) defines it as a special relationship between two persons with an unlimited exchange of favors, each of them being fully committed to the other; Osland (Reference Osland1990: 8) describes it as a special relationship between one person who needs something and another who has the ability to give something; and Yang (Reference Yang1988: 409) regards it as pre-existing relationships between classmates, people with shared origins and/or relatives, workplace superiors/subordinates, etc. A second set of conceptualizations regards guanxi as ties. Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1979) defines it as particularistic ties based on shared attributes, and Bian (Reference Bian, Beckert and Zafirovski2006: 312) describes it as a particular and sentimental tie with the potential to facilitate exchanges of favors between the connected parties. Bian (Reference Bian2018) identifies five types of guanxi ties (connectivity, sentimental connection, sentiment-derived instrumental ties, instrumental-particular ties, and obligational ties), which vary in form and significance depending on the situation. Guanxi has no formal network structure, but involves strong ties between family members, close kin, and long-term friends, who seek to protect each other from a hostile context (Burt & Opper, Reference Burt and Opper2017; Zhao & Burt, Reference Zhao and Burt2018). A third conceptualization, viewing guanxi as a problem-solving mechanism, is offered by Fan (Reference Fan2002: 372), who views it as a process of social interactions between two individuals who may or may not have a special relationship: if one asks for assistance, the other provides it or seeks further assistance from other connections. Many authors support and use Fan's definition (e.g., Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004; Luo, Reference Luo2007; Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2006). Other interpretations have cast guanxi as interpersonal friendships (Ang & Leong, Reference Ang and Leong2000); interpersonal connections (Xin & Pearce, Reference Xin and Pearce1996: 1641); reciprocal exchanges (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987); tight, close-knit networks, and a gate or pass (Yeung & Tung, Reference Yeung and Tung1996: 54).

We adopt a broad definition of guanxi as an informal norm of interpersonal exchange that regulates and facilitates privileged access to sentimental or instrumental resources at the dyadic or network level (Bian, Reference Bian2018; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019).

Features of Guanxi

A number of significant features underlie the cultivation, use, and preservation of guanxi. Guanxi networks are essentially social in nature (Arias, Reference Arias1998; Björkman & Kock, Reference Björkman and Kock1995). The origins of Chinese guanxi have been traced back to Confucian teachings and principles (Bian & Ang, Reference Bian and Ang1997; Kienzle & Shadur, Reference Kienzle and Shadur1997), which take a long-term view of social interactions. Guanxi can therefore last a lifetime (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019) and can even pass from one generation to another if maintained (Luo, Reference Luo2007). Guanxi is usually considered at the individual level (Chung, Reference Chung2019; Tsang, Reference Tsang1998) with relationships built among people, not organizations. However, the use of guanxi at the organizational level has increased, since employees are increasingly encouraged to use their personal guanxi for organizational purposes (Luo, Reference Luo1997). Context is highly relevant: giving a gift in one situation might be accepted as a customary practice, while in a different situation it might be seen as a bribe (Luo, Reference Luo2007). Guanxi's utilitarian core, whereby favors can be exchanged as a result of interpersonal links (Bian, Reference Bian2018), can operate at the organizational level, enabling organizations to benefit from each other's guanxi if there is complementarity of resources and a mutual strategic need (Luo, Reference Luo2007; Zhang, Kimbu, Lin, & Ngoasong, Reference Zhang, Kimbu, Lin and Ngoasong2020). Guanxi can also be transferred to a third party, if one person in relationship with two others is willing to link them (Luo, Reference Luo1997; Tsang, Reference Tsang1998). Members of guanxi networks are committed to each other through an unwritten but mutually understood code of equity and reciprocity (Luo, Reference Luo1997; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kimbu, Lin and Ngoasong2020). Disrespecting this code or refusing to return a favor can seriously damage a person's social reputation, leading to loss of face (Luo, Reference Luo1997). Overall, guanxi's multiple features are indicative of rich and comprehensive networks with both cultural and social elements.

Guanxi-Type Relationships Outside China

Many of the features of guanxi are not unique to Chinese society, but exist to some extent in all societies, including those in the Middle East (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b) and the West (Burt, Reference Burt2019; Burt & Burzynska, Reference Burt and Burzynska2017). However, the ways in which these relationships are nurtured and developed vary considerably, with notable differences between East and West (Fainshmidt et al., Reference Fainshmidt, Judge, Aguilera and Smith2018; Flambard-Ruaud, Reference Flambard-Ruaud2005; Kabasakal & Bodur, Reference Kabasakal and Bodur2002; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Sultan, Van De Bunt and Ramady2016; Yen et al., Reference Yen, Yu and Barnes2007). Even Burt (Reference Burt2019: 31), who argues that such networks exist in China and in Western societies, highlights a significant substantive difference between them: those in China are more hierarchical and more family-centric than those in the West. Burt and Burzynska (Reference Burt and Burzynska2017: 221-222) support this distinction, arguing that Chinese and Western networks have significant differences, while both strongly featuring trust and achievement.

Guanxi-type relationships in the Middle East

In the Middle East context, guanxi-type relationships are different. The tribal framework is preeminent: Arabs’ heavy reliance on these networks draws on historical cultural values and traditions which are totally different from networking in the West (ALHussan, Al-Husan, & Alhesan, Reference ALHussan, Al-Husan and Alhesan2017; ALHussan, AL-Husan, & Chavi, Reference ALHussan, AL-Husan and Chavi2014). Arab society has been shown to rely heavily on these networks (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993; Cunningham, Sarayrah, & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham, Sarayrah and Sarayrah1994; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2006; Weir & Hutchings, Reference Weir and Hutchings2005), which can be characterized as a strategy for exchanging benefits. The unique features of Arab networks, such as origins, closeness, characteristics, density of usage, etc., can be partly attributed to the specific characteristics and cultural factors of Middle Eastern societies (Barakat, Reference Barakat1993; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a). Since families are viewed as the fundamental unit of a society (Barakat, Reference Barakat1993; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a), their influence extends from basic decision-making (Barakat, Reference Barakat1993) to business and management practices (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006b; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2006), education, government, and society at large (ALHussan et al., Reference ALHussan, Al-Husan and Alhesan2017; Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993), and includes non-material gains such as licences, scholarships, parliamentary seats, and other benefits that ‘might enhance the well-being or social status of a person seeking it’ (Pawelka & Boeckh Reference Pawelka and Boeckh2004: 40). The powerful influence of tribal connections in the Arab world can also be seen in the way relationships are overseen and arguments resolved. Generally, social networks underpin this process too, with a delegate acting as mediator between tribes in dispute (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993). People with significant wealth or power use social networks extensively with a focus on their ultimate goals (Cunningham & Sarayrah, Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993). As Metcalfe (Reference Metcalfe2006) observed: ‘Working relations in the Arab world are influenced by the ability of an individual or an entity to be able to move in the right channels of power and influence to accomplish something’. This heavy dependence on tribal and family ties can be contrasted with Burt and Opper's (Reference Burt and Opper2017) findings from China that entrepreneurs’ primary source of support was more likely to be long-standing contacts than relatives: around 90% of the contacts providing support in the first decade of a business were non-family members.

It can be argued that a further distinction between guanxi-type relationships in the Middle East and those in the West and China is the underpinning of Islamic ethics and values (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Weir & Hutchings, Reference Weir and Hutchings2005: 92). In the Arab world, religion is a guide to action, as it determines action in every aspect of people's lives (Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a: 146). Most Arabs are Muslims, and Islam ‘shapes people's mindsets and opinions at a very deep level in addition to being responsible for many of the behavioral patterns that can be observed throughout the region’ (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2003: 77). Likewise, the origins of Chinese guanxi networks have been traced back to Confucian teachings and principles which guided behavioral patterns (Bian & Ang, Reference Bian and Ang1997; Kienzle & Shadur, Reference Kienzle and Shadur1997).

Overall, it can therefore be seen that social networks in the Arab world are significantly more important than mere connections: they are the route to securing individual and business benefits, and they are ubiquitous. The dimensions of guanxi-type relationships in general, and how they differ between Chinese and Middle Eastern cultures, are explored in the next section.

Dimensions of Guanxi-Type Relationships

Many studies have discussed the dimensions of guanxi (Chen, Reference Chen2001; Tsang, Reference Tsang1998; Wang, Reference Wang2007; Yang, Reference Yang1994; Yau et al., Reference Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin and Alan2000), illustrating it as a multi-dimensional construct. While there is no agreement about its dimensions, there is wide recognition – albeit in a fragmented manner – that its six main variables are bonding, empathy, reciprocity, personal trust, face, and affection. These will therefore be used in this study.

Bonding

Bonding is a social or business practice that functions by means of commonalities and common backgrounds, which is used to eliminate doubt between parties (Yau et al., Reference Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin and Alan2000). Its potential bases are kinship, fictive kinship, locality and dialect, workplace, and friendship (Kiong & Kee, Reference Kiong and Kee1998: 77–79). While particularly strong ties have been noted among family groups and long-term friends (Burt & Opper, Reference Burt and Opper2017; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019; Zhao & Burt, Reference Zhao and Burt2018), individuals with no common background can also develop relationships through collaboration and cooperation (Tsang, Reference Tsang1998).

Empathy

Empathy can be defined as the ability to understand someone else's desires and goals (Yau et al., Reference Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin and Alan2000). It reduces barriers to relationship building and ensures people are willing to help others in need (Wang, Reference Wang2007). Empathy is extremely significant within guanxi ties, since people want to fully understand their partners and their requirements. In the Chinese context, it focuses on the benefactor's behavior, guided by Confucian principles such as ‘Do unto others as you wish done unto yourself’ (Hwang, Reference Hwang1987). The same principles are embedded in Arab cultures, drawn from the teachings of Islam and Christianity. In a collectivist culture such as the Arab world, empathy is important to establish relationships and build trust before doing business (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2009; Barakat, Reference Barakat1993; Weir, Sultan, & Van De Bunt, Reference Weir, Sultan and Van De Bunt2019).

Reciprocity

Reciprocity refers to mutual assistance between network members without the need for compensation (Barnett, Yandle, & Naufal, Reference Barnett, Yandle and Naufal2013; Berger, Silbiger, Herstein, & Barnes, Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015). It aids long-term relationships as it enhances trust (El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009), as well as directly influencing business performance (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015; Bian, Reference Bian2018). A guanxi-type relationship carries the implicit potential of boundless exchanges of favors, and continues in the long term through a similarly implicit loyalty to others in the network, reflecting an informal code of reciprocity (Luo, Reference Luo2007). A person who receives favors but gives none will lose face (Barnes, Yen, & Zhou, Reference Barnes, Yen and Zhou2011). Reciprocity is among the norms that extend the influence of guanxi beyond kinship networks and into wider social interactions (Bian, Reference Bian2018). In a Chinese business relationship, one guanxi party is expected to provide support to another in difficulty, on the understanding that a return favor will be available when needed (Wang, Reference Wang2007). In the Middle East, reciprocity ensures a positive outcome, reduces uncertainty, and creates value (Mohamed & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamad2011).

Personal trust

Personal trust in the context of guanxi chiefly relates to establishing credibility via past history and reputation through the fulfilment of promises and obligations with mutual satisfaction and beneficial interactions (Kiong & Kee, Reference Kiong and Kee1998; Yau et al., Reference Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin and Alan2000). Trust can also be seen as an index by which to judge someone's moral integrity and an initial channel to enhance the relationship between two parties (Chen & Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2004). Generally, members of guanxi networks place great value in trust and credibility in both social and business contexts (Burt & Burzynska, Reference Burt and Burzynska2017; Burt & Opper, Reference Burt and Opper2017). By contrast, the level of interpersonal trust and the quality of relationships in the Middle East is determined largely by family origin (Ivens & Pardo, Reference Ivens and Pardo2007; Smith, Huang, Harb, & Torres, Reference Smith, Huang, Harb and Torres2012). In such collectivist cultures, personal trust is therefore important to establish relationships before business can proceed (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2003, Reference Al-Omari2009; Barakat, Reference Barakat1993; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Sultan and Van De Bunt2019). In Arab culture overall, goodwill, trust, and mutual respect are worth more than what is written down (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2009; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a).

Face

Face has been described as the public image of a person's or one's own prestige and reputation (Tsang, Reference Tsang1998), and as social status attained by completing recognized social roles in a community (Li et al., Reference Li, Zhou, Zhou and Yang2019). It is generated not by self-assessment but by the opinions of other people. Face can not only strengthen the exclusive attachment that members feel towards a guanxi network (Bian & Ikeda, Reference Bian, Ikeda, Alhajj and Rokne2014), but can influence the way an entire network is viewed. Overall, face can be seen as a sort of moral norm whereby all members of a group seek to gain it in order to maintain the group's dignity. In Chinese guanxi, face plays a major role in the preservation of networks (Chen, Reference Chen2001; Shou, Guo, Zhang, & Su, Reference Shou, Guo, Zhang and Su2011; Tsang, Reference Tsang1998), and has clear relevance in the business context as well as in social and moral spheres. This is no less true in Middle Eastern culture, where it plays a key role in relationship building by emphasizing the notions of continuity and collaboration (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015).

Affection

Affection is a significant dimension of guanxi, since networks rely on altruism, a desire to help people, and affection-based feelings such as sympathy, care, trust, and love in order to operate successfully (Bian, Reference Bian2018). The feelings and emotional attachments that exist within guanxi networks frequently reflect members’ closeness and the quality of the relationships between them: thus, it is a significant variable (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Yen and Zhou2011; Wang, Reference Wang2007). Yang (Reference Yang1994) highlights that emotional exchanges rather than obligations are key to guanxi. The significance of affection is not limited to Chinese networks; it is to be found across cultures and countries, including those in the Middle East. While its most intimate forms can expect to be found within families (Bian, Reference Bian2018), it is possible to create affection even in a business relationship by investing in its development (Shou et al., Reference Shou, Guo, Zhang and Su2011; Wang, Reference Wang2007).

Research Model and Hypotheses

Guanxi and relationship marketing are different concepts with their own unique characteristics, benefits, and pitfalls (Geddie et al., Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2005); however, the possibility of integrating them has long been mooted (Flambard-Ruaud, Reference Flambard-Ruaud2005; Tsang, Reference Tsang1998). While guanxi is an informal interpersonal relationship involving implicit mutual trust (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2006), relationship marketing is a formal, official agreement defined and protected by a legal organizational framework. Prior research has inferred an association between them that would be important given its potential to improve customer recruitment and retention (Björkman & Kock, Reference Björkman and Kock1995; Geddie et al., Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2002, Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2005). Other studies have recommended the importance of transferring guanxi-type relationships from the interpersonal to the organizational level (Flambard-Ruaud, Reference Flambard-Ruaud2005; Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2006).

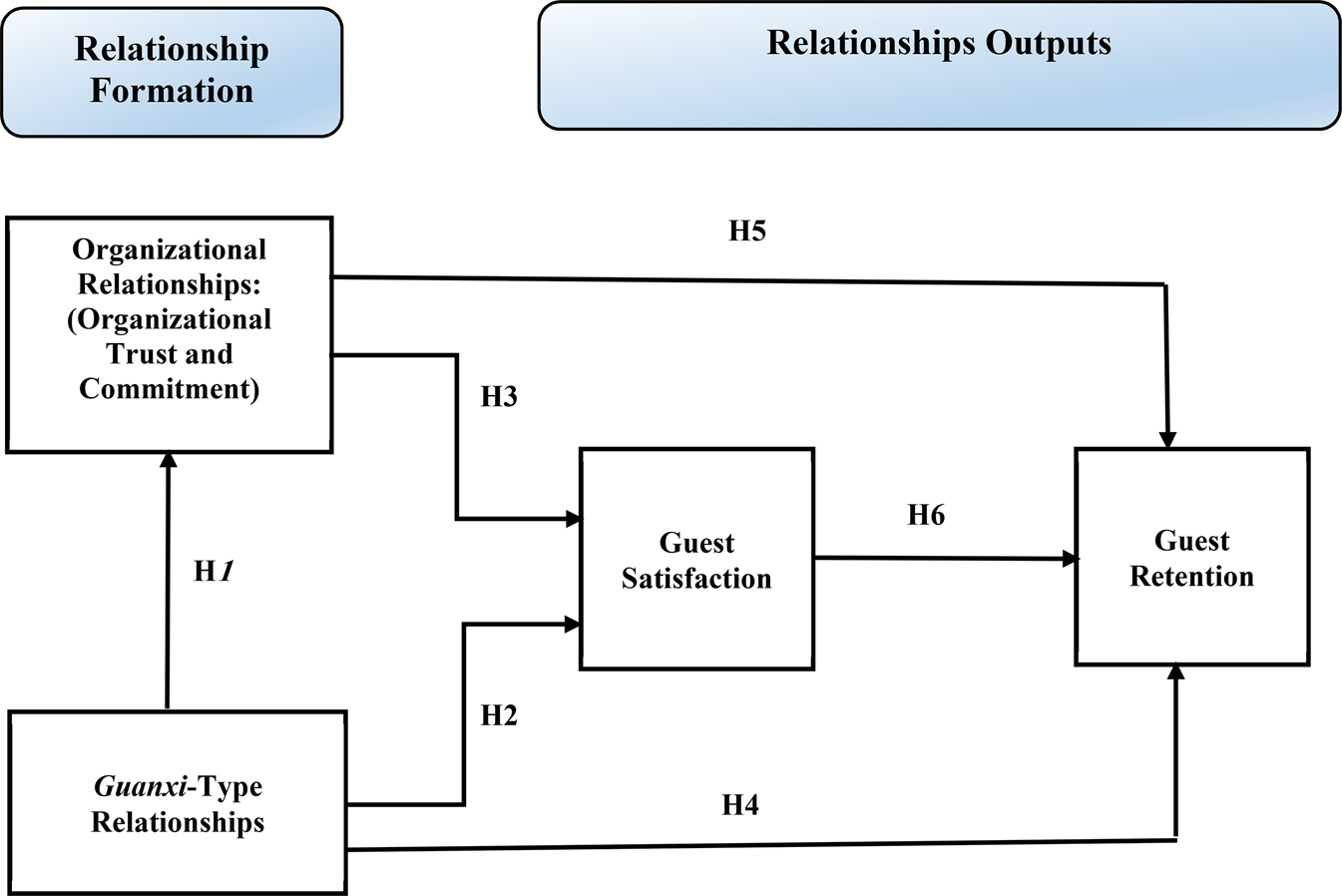

The model we present in this research (Figure 1) is based on the premise that relationship marketing aims to attract, maintain, and enhance customer relationships (Berry, Reference Berry2002), and that relationship marketing goes beyond the scope of guanxi (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2006), since it helps retain customers by building organizational relationships (Tang, Chou, & Chen, Reference Tang, Chou and Chen2008). Initially, the model assumes that firms encourage all their employees to use their personal guanxi networks (e.g., family, friends, and colleagues) for organizational purposes (e.g., generating business and new customers) by rewarding them with commission or bonuses. Dunfee and Warren (Reference Dunfee and Warren2001) support this assumption, arguing that managers can use guanxi-type relationships to access new customers. Since Arab people prefer to deal with those they already know, and consider that establishing a relationship before undertaking a business transaction is fundamental (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2003, Reference Al-Omari2009; Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015; Berger et al., Reference Berger, Herstein, McCarthy and Puffer2019; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a), using guanxi-type relationships can therefore be beneficial in the Middle Eastern context. This principle can be applied in many different business sectors, including the tourism and hospitality industry, where the relationship between a potential customer and a hotel's representative (employee) typically develops before a transaction occurs (Yau et al., Reference Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin and Alan2000). Indeed, Flambard-Ruaud (Reference Flambard-Ruaud2005) argues that in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, successful business transactions are largely subject to established relationships.

Figure 1. The research model

Our proposed model therefore incorporates guanxi principles into existing relationship marketing processes, in essence using guanxi-type relationships to attract customers and relationship marketing to keep them. First, firms would engage all the components of guanxi (bonding, empathy, reciprocity, personal trust, face, and affection) to draw in clients, and, after an initial transaction, would apply relationship marketing programs to build organizational trust and commitment. The conversion of personal to organizational relationships is aimed at ensuring a long-term relationship with the customer, since promoting organizational trust and commitment increase customer retention (Bruhn, Reference Bruhn2003), and retention contributes to long-term profits (Tseng, Reference Tseng2007). Several studies have highlighted the importance of this transfer (Barnes, Leonidou, Siu & Leonidou, Reference Barnes, Leonidou, Siu and Leonidou2015; Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2006), which enables firms to avoid the pitfalls of using only guanxi, while also providing a critical tool for gaining new clients comparatively cheaply. Once retention has been achieved, customers are themselves encouraged to use their personal guanxi to attract new clients, who in turn are invited to do the same. The final hypothesized outcome of this model is therefore improved customer satisfaction and retention.

Effect of guanxi-type relationships on organizational relationships

Organizational trust and commitment are basic elements in relationship marketing, since the level of trust and commitment between exchange partners is a significant measure of the strength of the organizational relationship (Morgan & Hunt, Reference Morgan and Hunt1994). In our model, firms would harness their employees’ personal networks (e.g., family, friends, locality, fictive kinship) to attract new customers, to be followed (after the initial transaction) by the deployment of traditional relationship marketing programs, to encourage repurchase behavior and link the consumer to the institution, generating organizational trust and commitment. Webster (Reference Webster1992) indicates that repeat transactions lead to relationship formation, while Palmatier, Jarvis, Bechkoff, and Kardes (Reference Palmatier, Jarvis, Bechkoff and Kardes2009: 13) find that relationship marketing programs significantly shape customers’ feelings of gratitude, which in turn leads to stronger organizational relationships. Yen, Abosag, Huang, and Nguyen (Reference Yen, Abosag, Huang and Nguyen2017) note that personal relationships can preserve existing organizational relationships as well as lubricating new ones. Interpersonal networks are therefore crucial in fostering effective organizational relationships (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015). Based on these arguments, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1: Guanxi-type relationships have a significant positive effect on organizational relationships.

Effects of guanxi-type relationships and organizational relationships on guest satisfaction

Organizational relationships have been shown to be the most important variable in customer satisfaction, both in building (Berry, Reference Berry, Berry, Shostack and Upah1983) and increasing it (Smith & Barclay, Reference Smith and Barclay1997), as well as in generating intention to remain (Morgan & Hunt, Reference Morgan and Hunt1994; Berry & Parasuraman, Reference Berry and Parasuraman1991). Other studies agree that the level of organizational relationship influences both satisfaction and retention (Sin, Tse, Yau, Chow, Lee, & Lau, Reference Sin, Tse, Yau, Chow, Lee and Lau2005).

Berger et al. (Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015) suggest that in an Arab context, satisfaction can be considered as an outcome of a guanxi-type relationship. Yen et al. (Reference Yen, Abosag, Huang and Nguyen2017) note that human interaction, personal relationships, and friendship can sustain business relationships and lead to all the parties feeling satisfied. In a collectivist culture such as the Arab world, each of the guanxi-type relationship dimensions plays a significant role in building sustainable business relationships with a high level of satisfaction. Empathy along with personal trust, reciprocity, and face all play a key role of establishing business relationships and building satisfaction (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2003, Reference Al-Omari2009; Barakat, Reference Barakat1993; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Sultan and Van De Bunt2019). The importance of empathy in maintaining business relationships and customer satisfaction in the Arab world is also underlined by the fact that the Middle Eastern communication model is receiver-centered, in contrast to the sender-centered Western model. In the Middle East, reciprocity also aids long-term relationships and satisfaction as it ensures a positive outcome, reduces uncertainty and ambiguity, and creates value (El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009; Mohamed & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamad2011), as well as directly influencing business performance (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015; Bian, Reference Bian2018). Personal trust is another vital component to establish successful business relationships and ensure satisfaction afterwards, particularly in a culture where the word is the bond, what people shake hands on matters more than what they sign (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2003, Reference Al-Omari2009; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Sultan and Van De Bunt2019). Moreover, in Middle Eastern culture, face plays a key role in relationships by emphasizing the notions of continuity, collaboration, and satisfaction (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015). Affection also exists in the business relationship (Shou et al., Reference Shou, Guo, Zhang and Su2011; Wang, Reference Wang2007). It can be a sentiment-driven instrumental business tie with expectations of reciprocity and relationship retention (Bian, Reference Bian2018; Butt, Shah, & Sheikh, Reference Butt, Shah and Sheikh2020). Elsharnouby and Parsons (Reference Elsharnouby and Parsons2010: 1369) argued that emotions in business relationships lead to a ‘moral obligation’ of parties to give help and exchange favors which lead to satisfaction. Similarly, Al-Omari (Reference Al-Omari2009) outlined the essential role that emotions play in the cohesion of people in Arabic culture and considered affection as one of the main reasons for establishing satisfaction in business relationships.

In summary, guanxi-type relationships and strong organizational relationships are seen as key variables leading to satisfaction, cooperative behaviors among parties, long-term relationships, and the success of relationship marketing (Morgan & Hunt, Reference Morgan and Hunt1994; Sin et al., Reference Sin, Tse, Yau, Chow, Lee and Lau2005). We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 2: Guanxi-type relationships have a significant positive impact on guest satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3: Organizational relationships have a significant positive impact on guest satisfaction.

Effects of organizational relationships, guanxi-type relationships, and satisfaction on guest retention

Customer retention – the willingness to repurchase from the company in the future (Gupta & Zeithaml, Reference Gupta and Zeithaml2006) – has been described as a ‘state of continuation of a business relationship with the firm’ (Keiningham, Cooil, Aksoy, Andreassen, & Weiner, Reference Keiningham, Cooil, Aksoy, Andreassen and Weiner2007: 364). Driven by customer satisfaction, it shows the presence of a successful relationship between customer and organization (Farquhar, Reference Farquhar2005; Reichheld, Reference Reichheld1996), with many advantages (Bruhn, Reference Bruhn2003; Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, Reference Zeithaml, Berry and Parasuraman1996), including greater purchasing frequency and the possibility of cross-selling. Satisfied customers may also be willing to pay a premium price to reduce alternative risk (Zeithaml et al., Reference Zeithaml, Berry and Parasuraman1996), and might encourage friends and relatives to buy from the company, while not discouraging current clients (Boulding, Kalra, Staelin, & Zeithaml, Reference Boulding, Kalra, Staelin and Zeithaml1993). In addition, customer satisfaction has also been shown to result in more repeat purchases and lower switching rates (Al-Msallam, Reference Al-Msallam2015), and to lead to increased customer loyalty, since satisfied customers are more likely to repurchase (Akbari, Nazarian, Foroudi, Amiri, & Ezatabadipoor, Reference Akbari, Nazarian, Foroudi, Amiri and Ezatabadipoor2020). Prior studies have focused more on retention and recovery than on attracting new business (Bruhn, Reference Bruhn2003), since customer acquisition is considered to be between five and 10 times more costly than retention (Gummesson, Reference Gummesson1999).

Building trust and commitment through organizational relationships is key to retention (Palmatier et al., Reference Palmatier, Jarvis, Bechkoff and Kardes2009; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Chou and Chen2008; Tseng, Reference Tseng2007), creating intent to stay in the relationship, and influencing the parties' long-term orientation (Abosag & Naudé, Reference Abosag and Naudé2014). In Arab culture, a combination of guanxi-type and organizational relationships could help to retain customers over the long term (Bejou, Ennew, & Palmer, Reference Bejou, Ennew and Palmer1998; Little & Marandi, Reference Little and Marandi2003; Mittal & Lassar, Reference Mittal and Lassar1998), while in the Chinese context, the guanxi components of reciprocity and face may have a positive correlation with relationship longevity (Yen & Barnes, Reference Yen and Barnes2011).

In Arab culture, retention can be considered as an outcome of a guanxi-type relationship and its dimensions. The closer the bond between the customers and the firm's representative, the more doubt is removed, and the more relationship retention is expected (Tsang, Reference Tsang1998). In addition, in the Middle East, empathy among business partners means they are expected to anticipate the exchange party's needs and feelings without being told; accordingly, this increases the willingness of all parties to maintain a long-term business relationship (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2009; Wang, Reference Wang2007; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Sultan and Van De Bunt2019; Yau et al., Reference Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin and Alan2000). Moreover, continuous reciprocity aids long-term relationships as it enhances trust and reduces ambiguity (El-Said & Harrigan, Reference El-Said and Harrigan2009; Mohamed & Mohamad, Reference Mohamed and Mohamad2011). In addition, personal trust in Arab culture precedes business and other transactions (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2003, Reference Al-Omari2009; Hutchings & Weir, Reference Hutchings and Weir2006a). Accordingly, the level of interpersonal trust in the Middle East is of prime importance and supports initiating and retaining long-term relationships (Al-Omari, Reference Al-Omari2003, Reference Al-Omari2009; Barakat, Reference Barakat1993; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Sultan and Van De Bunt2019). Elsharnouby and Parsons (Reference Elsharnouby and Parsons2010: 1370) argue that personal trust has a prominent role in business interactions as the Arab world is a risk-averse society. Hyder and Fregidou-Malama (Reference Hyder and Fregidou-Malama2009: 266) indicate that personal trust is a cultural requirement and presenting in all deals to help maintain long-term relationships. In the Middle Eastern culture, face also plays a major role in maintaining network relationships (Chen, Reference Chen2001; Shou et al., Reference Shou, Guo, Zhang and Su2011), and has clear relevance for business as well as in social and moral spheres, emphasizing the notions of continuity and collaboration (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Silbiger, Herstein and Barnes2015). Al-Omari (Reference Al-Omari2009) and Barakat (Reference Barakat1993) highlight Arab sensitivity to ‘losing face’ – a concept which is closely related to shame in the Arab world – which makes the Arab keen to keep long-term social and business relationships. Finally, affection is key to establishing lasting and firm business relationships (Shou et al., Reference Shou, Guo, Zhang and Su2011; Wang, Reference Wang2007). Al-Omari (Reference Al-Omari2009) views emotions as being prevalent in relationships among people in the Arab world and even in a business context. Furthermore, affection can become a sentiment-driven instrumental tie with expectations of reciprocity and relationship retention (Bian, Reference Bian2018; Butt et al., Reference Butt, Shah and Sheikh2020).

This research explores whether customers introduced through guanxi-type relationships and then engaged in organizational relationships can be satisfied and retained in the long term; whether guanxi-type relationships influence customer retention or only client introduction; and whether organizational relationships and satisfaction eventually contribute to guest retention. We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 4: Guanxi-type relationships have a significant positive impact on guest retention.

Hypothesis 5: Organizational relationships have a significant positive impact on guest retention

Hypothesis 6: Guest satisfaction has a significant positive impact on guest retention guanxi.

METHODS

Variables and Measures

After defining the research variables, specifying the constructs, and drawing the boundaries, we generated a set of items to measure each variable, drawn from reliable measures of relevant constructs that had been published and validated in the prior literature. Guanxi-type relationships were conceptualized as a second-order construct consisting of six first-order components (bonding, empathy, reciprocity, personal trust, face, and affection), which were each measured by four or five items (see Appendix I, Table I). We borrowed or adopted these items from Sin et al. (Reference Sin, Tse, Yau, Chow, Lee and Lau2005), Lee and Dawes (Reference Lee and Dawes2005), Mavondo and Rodrigo (Reference Mavondo and Rodrigo2001), Smith and Barclay (Reference Smith and Barclay1999), and Yen and Barnes (Reference Yen and Barnes2011). Organizational relationships were operationalized using eight items from Sin et al. (Reference Sin, Tse, Yau, Chow, Lee and Lau2005) and Ndubisi (Reference Ndubisi2007); while the consequences of guanxi-type relationships (customer satisfaction and retention) were measured using items from Eid (Reference Eid2015), Eid and El-Gohary (Reference Eid and El-Gohary2015), Lee and Jun (Reference Lee and Jun2007), and Trasorras, Weinstein, and Abratt (Reference Trasorras, Weinstein and Abratt2009). These trusted measures formed the basis of a questionnaire that was designed and tested in line with the advice of previous scholars (Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988; Churchill, Reference Churchill1979; Eid, Reference Eid2009; Netemeyer, Bearden, & Sharma, Reference Netemeyer, Bearden and Sharma2003). We piloted the survey with 20 hotel guests to refine the wording and make it more relevant to practices in the Middle East; this was then undertaken with a group similar to the final target population (Salaheldin & Eid, Reference Salaheldin and Eid2007; Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, Reference Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill2012). The pre-testing exercise resulted in only minor changes to the existing scales, e.g., to clarify the wording.

To avoid the risk of common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003), we carefully designed the questionnaire to minimize its occurrence, and assessed its potential presence in the data in two ways (Podsakoff & Organ, Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986), which confirmed it was not a serious concern. Harman's single-variable test showed that the largest factor accounted for 30.18% (variances ranged from 17.56% to 23.41%), and no single factor accounted for more than 50% of the variance; while Lindell and Whitney's (Reference Lindell and Whitney2001) marker variable method showed that all coefficients remained significant after the marker variable had been controlled.

Context of Data Collection and Sampling

The hotel industry is the context of the data collection for this study. The global tourism and hospitality industry has expanded considerably in the past few years, leading to recognition of its importance to the development agenda, given that it is already transforming entire communities as well as individual lives (UNWTO International Tourism Highlights, 2019). By 2019, global export earnings from tourism stood at US $1.7 trillion (UNWTO), while the global hotel industry had an estimated retail value of US $600.49 billion in 2018 (Statista, 2020). These rising figures have been matched by an expansion in jobs and in the nature of the services provided, including the growing popularity of tourism that reflects the cultural heritage of host communities (Akbari et al., Reference Akbari, Nazarian, Foroudi, Amiri and Ezatabadipoor2020).

Despite these significant gains, the hospitality industry as a whole, and the hotel sector within it, remain at the mercy of internal and external factors (Farrington, Curran, Gori, Gorman, & Queenan, Reference Farrington, Curran, Gori, Gorman and Queenan2017) such as political events, economic downturns, social unrest, and fluctuating year-on-year or seasonal demand. The use of guanxi-type relationships is increasingly recognized by both practitioners and academics as an important source of stability in changing external circumstances. In support, Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Kimbu, Lin and Ngoasong2020) argue that interpersonal relationships (e.g., guanxi-type relationships) are playing a crucial role in the tourism and hospitality sector. However, deeper insights are still needed, especially in the service context of the hotel industry (Akbari et al., Reference Akbari, Nazarian, Foroudi, Amiri and Ezatabadipoor2020; Mohammed & Rashid, Reference Mohammed and Rashid2018). Furthermore, focusing on market-specific traits of the target market is key to ensuring positive brand outcomes and gaining customer support (Akbari et al., Reference Akbari, Nazarian, Foroudi, Amiri and Ezatabadipoor2020), emphasizing the importance of fully understanding the cultural and social factors of a market such as the Middle East, which could benefit significantly from the economic and development potential of the ongoing expansion of its tourism and hospitality sector.

We conducted the main data collection from January to May 2017, using purposive sampling. The unique target population was hotel guests in the Middle East who had been introduced by a member of staff or another guest with whom they had a personal relationship (guanxi). Since our aim was to analyze the effects of guanxi-type relationships and organizational relationships on guest retention in the Middle East, 17 countries across the region were selected, and 300 suitable hotels were identified in capitals or other major cities, located in areas that represented important destinations for guests. We distributed 1,200 questionnaires evenly between the hotels, of which 651 were completed and returned. Fourteen were eliminated owing to incomplete answers, leaving a total of 637 useable questionnaires (an overall response rate of 53.08%). These responses were spread across the 17 countries in the following proportions: Bahrain 2.4%, Egypt 13.3%, Iran 2.3%, Iraq 2.6%, Jordan 5.1%, Kuwait 3.2%, Lebanon 10.3%, Libya 3.1%, Oman 3.2%, Palestine 3.1%, Qatar 4.5%, Saudi Arabia 9.6%, Sudan 2.8%, Syria 3.1%, Turkey 12.3%, UAE 17.3%, and Yemen 1.8%. The demographics of the respondents are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Analysis of the descriptive statistics of the sample

RESULTS

Following Anderson and Gerbing's (Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988) recommendation, we used a two-step approach separating the measurement model from the structural model. We assessed the psychometric properties (discriminant validity, convergent validity, and reliability) of the measures used before using structural equation modelling to examine the hypothesized relationships.

Reliability and Validity of the Measures

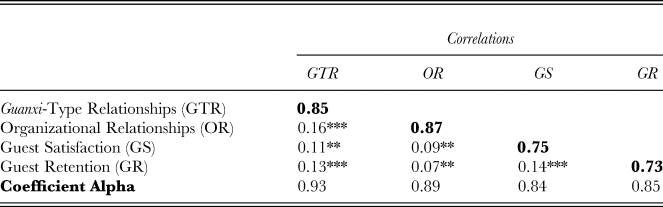

First, we calculated Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient and items-to-total correlation. This analysis led to the deletion of two items from the guanxi-type relationships construct and one from the organizational relationships construct. All the scales had reliability coefficients ranging from 0.84 to 0.93, which all exceeded the cut-off level of 0.65 set for basic research (Bagozzi, Reference Bagozzi1994: 96), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Reliability analysis

We then conducted exploratory factor analysis (see Appendix I, Table I) using all the items (with varimax rotation) to check the unidimensionality of the underlying factor structure. Elements which did not have dominant loadings greater than 0.50 or cross-loadings less than 0.50 were deleted (Hair, Black, Babin, Ralph, & Ronald, Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Ralph and Ronald2006). Using an eigenvalue of 1.0 as the cut-off point, four constructs were extracted (explaining more than 74.51% of the extracted variance).

Measurement Model Testing

To achieve strong convergent and discriminant validity, we used confirmatory factor analysis to examine the four measures. Convergent validity explains how the items of a certain variable congregate or share a high percentage of variance (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Ralph and Ronald2006). As the average variance extracted (AVE) for all the measures was more than 0.50, convergent validity was met. The results, presented in Table 3, show that the AVE values were higher than any squared correlation among the variables, hence indicating good discriminant validity of the constructs and the measures were practically different (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981).

Table 3. Measurement model results: Confirmatory factor analysis

Notes: The diagonals represent the average variance extracted and the lower cells represents the squared correlation among constructs. **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01

Structural Model Testing

After confirming the relevance of the measurement model, we developed and tested a structural model. We used factor scores to represent single item indicators for each construct in the model, and performed path analysis using the maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) method (Jöreskog & Sorbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sorbom1982). The results and measures for model fit are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Standardized regression weights

Note: ***P < 0.01

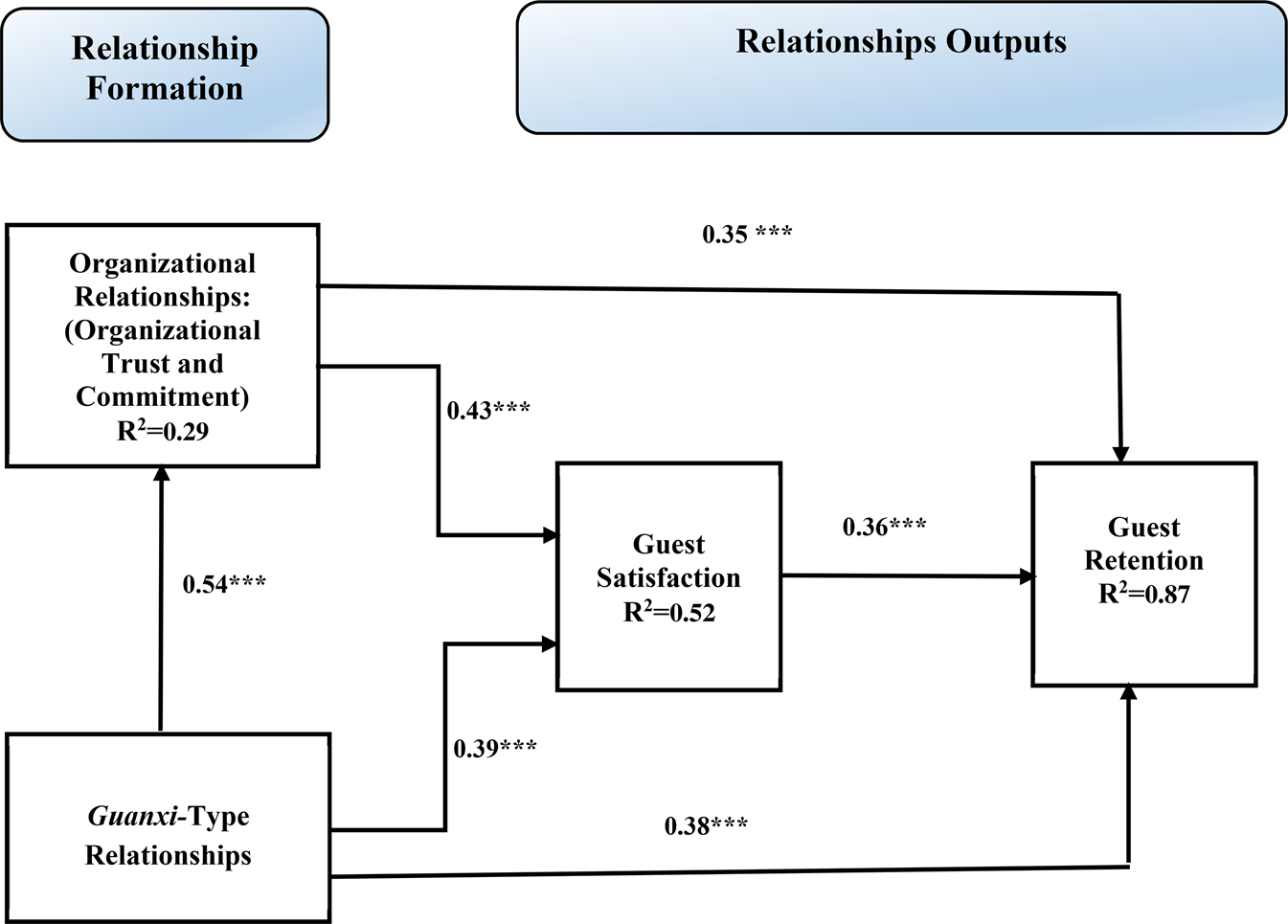

Before testing the hypotheses, we used different non-normal distributions tests to check the normality of the constructs (Bagozzi & Yi, Reference Bagozzi and Yi1988). Skewness, kurtosis, and the Mahalanobis distance statistics of the final measures were checked (Bagozzi & Yi, Reference Bagozzi and Yi1988). No deviation from normality was found for any measure. All the constructs were normally distributed, with deviation well within acceptable ranges. We then progressed to using the MLE method to establish the model. Figure 2 illustrates the path diagram for the causal model.

Figure 2. The tested model

Since there is no definitive standard of fit, we used different indicators. The Chi-square test was not statistically significant, which indicated a good fit. The other fit indicators, along with the squared multiple correlations, reflected a good overall fit with the data (GFI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.88, CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.04). As these indicators were acceptable, we decided the structural model was an appropriate tool for hypothesis testing.

RESULTS

The conceptual model and hypotheses were supported by the findings. The estimated standardized parameters for the causal relationships are shown in Table 4. Firstly, guanxi-type relationships were found to have a significant impact on the formation of organizational relationships (Hypothesis 1) (standardized estimate = 0.54, P < 0.001). Therefore, Hypotheses 1 was accepted. Secondly, both guanxi-type relationships (Hypothesis 2) (standardized estimate = 0.39, P < 0.001) and organizational relationships (Hypothesis 3) (standardized estimate = 0.43, P < 0.001) were found to significantly affect guest satisfaction. Therefore, Hypotheses 2 and 3 were accepted. Finally, the suggested factors were found to positively affect guest retention as follows: guanxi-type relationships (Hypothesis 4) (standardized estimate = 0.38, P < 0.001), organizational relationships (Hypothesis 5) (standardized estimate = 0.35, P < 0.001), and guest satisfaction (Hypothesis 6) (standardized estimate = 0.36, P < 0.001). Therefore, Hypotheses 4, 5, and 6 were accepted. The empirical analysis shows that most of the hypothesized relationships are, as expected, significant. The three suggested variables (guanxi-type relationships, organizational relationships, and guest satisfaction) jointly explain 87% of the variance in guest retention.

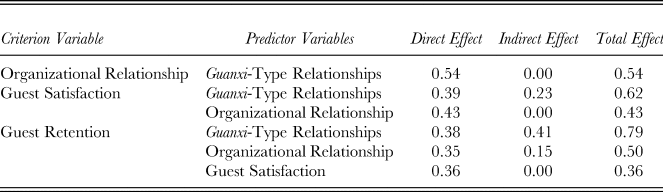

Because the causal effects of guanxi-type relationships and organizational relationships on guest retention can be either direct or indirect, i.e., they are mediated via the effect of guest satisfaction, we calculated the indirect causal effects and their total. Table 5 shows the direct, indirect, and total effects of the suggested factors.

Table 5. Direct, indirect, and total effect of CRM usage

DISCUSSION

Our results shed light on a number of aspects of guanxi-type relationships in the Middle East, including their implications for organizational relationships and customer retention. These are discussed in detail in the following sections.

Guanxi-Type Relationships

We have demonstrated that the dimensions of guanxi-type relationships introduced in the Chinese context can contribute to the formation of such relationships in the Middle East. All the related hypotheses were supported. The associations we have shown between guanxi-type relationships, organizational relationships, guest satisfaction, and retention offer valuable new insights for the hospitality industry in the Middle East, which currently uses only relationship marketing to build organizational relationships with customers (Flambard-Ruaud, Reference Flambard-Ruaud2005; Geddie et al., Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2005). Organizational relationship could become a natural progression from guanxi-type relationships (Geddie et al., Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2005). By examining the factors influencing guanxi-type relationships in the Middle East, and the outcomes of these relationships in a hospitality context, we have also demonstrated how each proposed dimension of guanxi presents a chance to use a strategy based on these relationships, with the general aim of improving both guest satisfaction and retention.

Organizational Relationships

Our findings that guanxi-type relationships have a direct and significant influence on organizational relationships are in agreement with those of Nicholson, Compeau, and Sethi (Reference Nicholson, Compeau and Sethi2001). Notably, this link had the highest coefficient in our model (0.54), supporting our theoretical view of the crucial role played by personal relationships in the development of organizational relationships. This finding shows that interpersonal relationships are a key antecedent of organizational relationships in the Middle East. In other words, without guanxi-type relationships, organizational relationships might not develop.

Guest Satisfaction

Our results support previous findings that organizational relationships are central to customer satisfaction and retention. For example, Anosike and Eid (Reference Anosike and Eid2011) and Sin et al. (Reference Sin, Tse, Yau, Lee and Chow2002) found that an increase in trust between customer and supplier raised the likelihood of building satisfaction and a long-term relationship. Furthermore, our findings, which were obtained in Middle Eastern collectivist cultures, support a number of previous theoretical views. For instance, Abosag and Naudé (Reference Abosag and Naudé2014) argued that this special type of relationship (guanxi) had a greater chance of achieving customer satisfaction than normal, less culturally dependent types of relationships.

Guest Retention

Guanxi-type relationships, organizational relationships, and guest satisfaction were collectively found to explain 87% of guest retention. The highest coefficient in the model (0.38) was the association between guanxi-type relationships and retention. We have therefore shown that establishing better interpersonal relationships allows hotels to interact with, respond to, and communicate more effectively with guests, leading to a significant improvement in retention rates. Converting these interpersonal ties into the type of organizational relationship central to relationship marketing (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2006) increases customer satisfaction and customer retention (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Chou and Chen2008; Tseng, Reference Tseng2007). Relationship marketing programs can therefore be supplemented in the Middle Eastern context by adding the use of guanxi-type relationships. This also renders the programs more adaptable to non-Western cultural characteristics and problems (e.g., lack of trust) (Flambard-Ruaud, Reference Flambard-Ruaud2005). The catalytic effect of guest satisfaction on retention was also clearly shown.

We were initially surprised to find that guanxi-type relationships had a similar effect to organizational relationships and guest satisfaction on retention. However, we realized this was predictable, since the direct effect is enhanced by the indirect positive effect (0.41); it is not just the guanxi-type relationships themselves that lead to positive perceptions and retention, but also the hotels’ efforts to build on them by developing organizational relationships.

Managerial Contributions

We have clearly shown the importance of integrating guanxi into business practices, given its potential to improve customer recruitment, satisfaction, and retention, thereby delivering significant advances for the company. It also enhances managers’ understanding of the different variables that make up guanxi-type relationships, enabling them to deploy better positioning strategies. On the basis of our results, Middle Eastern hotels should consider applying guanxi-type relationships and converting them into organizational relationships (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2006), thus improving guest satisfaction and retention (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Chou and Chen2008; Tseng, Reference Tseng2007). In this hybrid strategy, hotels would use employees’ interpersonal relationships to attract new guests as a precursor to the building organizational ties through relationship marketing. The many benefits of this strategy include building long-term relationships, avoiding the risks of strategies based only on guanxi-type relationships (Arias, Reference Arias1998), and attracting new customers at little cost (Dunfee & Warren, Reference Dunfee and Warren2001).

Our findings also enhance manager understanding of the interplay between organizational relationships, guest satisfaction, and guest retention, offering significant advantages to hotels (Zeithaml & Bitner, Reference Zeithaml and Bitner1996). Eid and El-Gohary (Reference Eid and El-Gohary2015) note that retained customers promote the company among their relatives and friends. Such positive word-of-mouth communication has a significant indirect effect on company returns. In support, Al-Msallam (Reference Al-Msallam2015), states that customer satisfaction leads to lower switching rates, and more repeat purchases. Similarly, satisfaction is seen as a prerequisite to developing customer loyalty, with satisfied customers showing more loyalty in their purchase decisions (Akbari et al., Reference Akbari, Nazarian, Foroudi, Amiri and Ezatabadipoor2020). Finally, our results show managers the importance of training employees so they build trusting relationships with guests and show empathy when handling their problems, as this strengthens organizational relationships. This should also help increase guest bonding with the hotel (Geddie et al., Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2005).

Theoretical Contributions

Our study makes a number of theoretical contributions. Firstly, it introduces a novel, unified model integrating guanxi into the existing relationship marketing framework. This shows the potential for using interpersonal relationships to attract customers and organizational relationships to retain them. This theoretically derived model has implications for the recruitment, satisfaction, and retention of customers, as well as offering valuable insights into cultural factors. Our study therefore contributes significantly to both the guanxi and relationship marketing literature by linking the two strands and creating a new concept. While some prior studies had inferred an association between social networks and relationship marketing (Geddie et al., Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2002, Reference Geddie, DeFranco and Geddie2005; Shaalan et al., Reference Shaalan, Reast, Johnson and Tourky2013), none had sought to link them, and no unified model previously existed. Furthermore, we have tested this model quantitatively and provided evidence of its applicability and effectiveness in the hotel sector in the Middle East. By introducing a means of converting guanxi-type ties into the organizational links involved in relationship marketing, we have also demonstrated a new route to increased customer satisfaction and retention.

Furthermore, we clearly show the outcomes of integrating guanxi-type relationships into marketing strategies in the Middle East. Our results can be considered unique, since this is the first study to deal with this problem and the unique unit of analysis, namely hotel guests in the Middle East who had been introduced by an employee or another guest with whom they had a personal relationship. Previous studies on relationship marketing, which considered the customer as the unit of analysis, dealt only with the business customer or final consumer. In addition to providing the first empirical evidence that a company can attract customers using guanxi and retain them using marketing strategies, we validate previous research on the impact of relationship marketing on customer retention, by testing relationship marketing and social network theories in a new geographical area (the Middle East), with a different unit of analysis and a unique problem. We therefore extend both the guanxi and relationship marketing literature by providing much-needed empirical support for the use and influence of guanxi-type relationships into the framework of relationship marketing in the Middle East.

Finally, we contribute to the literature by providing empirical evidence from the Middle East – an under-researched region in terms of business-to-customer relationships – on the role of guanxi-type relationships and organizational relationships in enhancing customer satisfaction and retention.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

As with any research, there are some limitations. Since this study was conducted exclusively in the Middle East, its outputs should be interpreted with care outside collectivist cultures or those with guanxi-type relationships, and cannot be considered as generalizable to Western cultures without further exploration. More research is therefore needed on all aspects of relationships based on social networks in different regions. The applicability and effectiveness of our research model should be tested in these settings. A comparative study applying the model in different cultures, including Asia and the West, would also enhance understanding of the nature of social networks in varying settings. There is also a need for both more qualitative and quantitative studies on all aspects of social networks in Western, Arab, and Asian cultures.

Since our research targeted only hotel guests, future studies using the model in different Middle Eastern sectors would strengthen generalizability, and comparing these results with our findings would also enrich the literature. Another potential limitation comes from the quantitative, customer-centered design of the empirical study. Future research could explore managers’ and employees’ perspectives, or follow a qualitative design to explore the constructs in greater depth, as well as testing the applicability of the concepts and the model in business-to-business contexts. Finally, our cross-sectional sampling approach means the potential causal impacts between the constructs can be inferred from the underlying theory rather than from the data itself (Rudestam & Newton, Reference Rudestam and Newton2007); a longitudinal research design would help confirm the potential causal relationships in our study. We hope our findings augment the literature and provide a reference point from which subsequent research can evolve.

CONCLUSION

Our study has investigated guanxi holistically and has expanded understanding of its dimensions beyond China, specifically in the Middle East, while also highlighting its differences with Western networks. We have explored the effects of incorporating guanxi-type relationships into existing relationship marketing frameworks in Middle Eastern countries; how these relationships affect guest satisfaction and retention; and how they can be successfully transformed into organizational relationships. All six of our hypotheses were supported.

Our main contribution is the introduction of a model blending guanxi-type relationships with relationship marketing. Overall, our findings indicate that: (a) guanxi-type relationships in the Middle Eastern have six dimensions – bonding, empathy, reciprocity, personal trust, face, and affection; (b) guanxi-type relationships, and organizational relationships are antecedents of Middle Eastern guests’ satisfaction; and (c) guanxi-type relationships, organizational relationships, and guest satisfaction have positive impacts on intention to return.

APPENDIX I

Scale Items, Factor Loadings, and Sources