No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

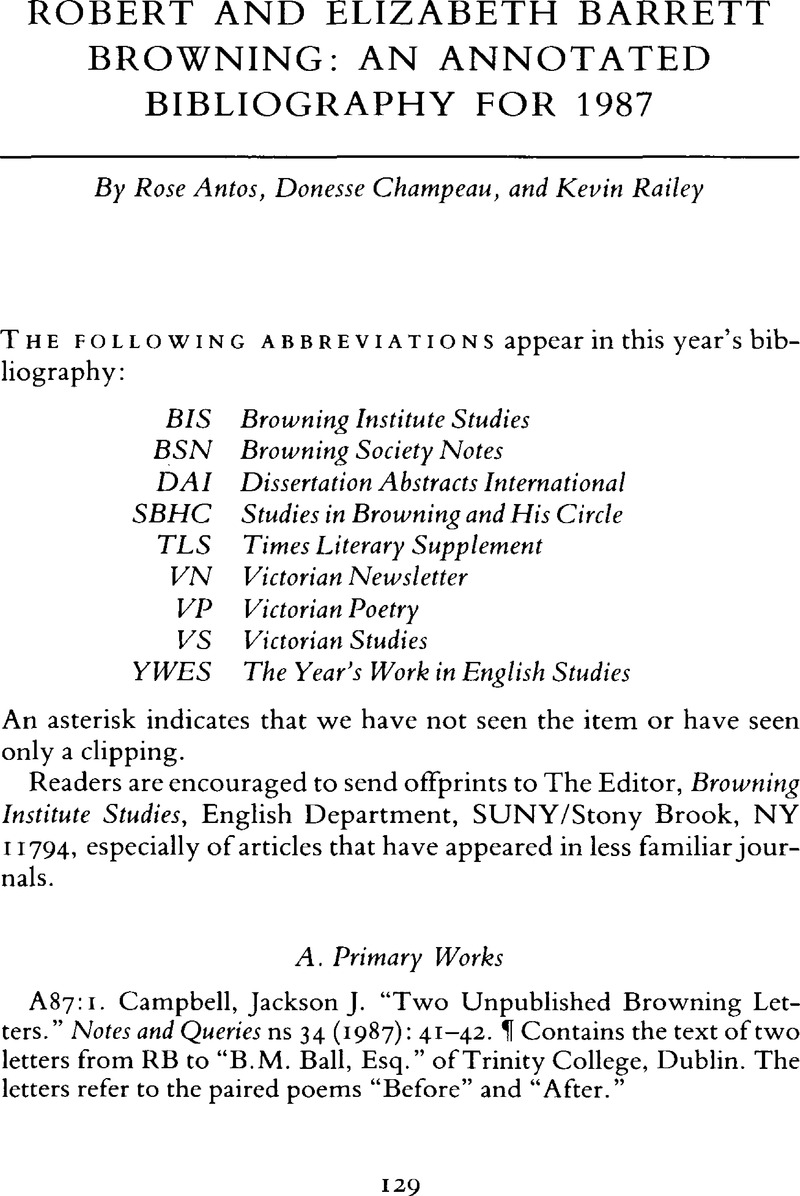

Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: An Annotated Bibliography for 1987

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2008

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Browning Bibliography

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1989

References

A87:1.Campbell, Jackson J. “Two Unpublished Browning Letters.” Notes and Queries ns 34 (1987): 41–42. ¶ Contains the text of two letters from RB to “B.M. Ball, Esq.” of Trinity College, Dublin. The letters refer to the paired poems “Before” and “After.”Google Scholar

A87:2.Ivanov, Anatoly, illustrator. The Pied Piper of Hamelin. By Browning, Robert. [See A86:1.]Google Scholar

A87:3.Kelley, Philip, and Hudson, Ronald, eds. The Brownings' Correspondence, Volume 3. [See A85:5.]Google Scholar

A87:4.Kelley, Philip, and Hudson, Ronald, eds. The Brownings' Correspondence, Volume 5: January 1841–May 1842. Winfield, KS: Wedgestone Press, 1987. xii + 428 pp.Google Scholar

A87:5.Lasner, Mark Samuels. “Browning's First Letter to Rossetti: A Discovery.” BIS 15 (1987): 79–90. ¶ Comments about and transcription of a probable copy of RB's first letter to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, found in poet William Allingham's commonplace book. Letter contains references to Pauline and Paracelsus.Google Scholar

A87:6.Machin, Patricia, comp. and illustrator. Browning. By Browning, Robert. Topsfield, MA: Salem House, 1987. [See A85:6.]Google Scholar

A87:7.Meredith, Michael, ed. More Than Friend: The Letters of Robert Browning to Katharine de Kay Bronson. [See A85:7.]Google Scholar

A87:8.Raymond, Meredith B., and Sullivan, Mary Rose, eds. Women of Letters: Selected Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Mary Russell Mitford. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1987. 293 pp.Google Scholar

A87:9.Stack, V.E., ed. The Love Letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett. London: Century, 1987. [See A69:10.]Google Scholar

B. Reference and Bibliographical Works and Exhibitions

B87:1.Anderson, Vincent B.Robert Browning as a Religious Poet: An Annotated Bibliography. [See B84:1.]Google Scholar

B87:2.Chaudhuri, Brahma, ed. and comp. Annual Bibliography of Victorian Studies, 1985. Edmonton, Alberta: LITIR Database, 1987: 112–19.Google Scholar

B87:3.Cohen, Edward H., ed. “E. Browning” and “R. Browning” in “Victorian Bibliography for 1986.” VS 30 (1987): 643–45.Google Scholar

B87:5.Garrison, Virginia, and Railey, Kevin. “Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: An Annotated Bibliography for 1985.” BIS 15 (1987): 177–89.Google Scholar

B87:6.Maynard, John. “Guide to Year's Work in Victorian Poetry: Robert Browning.” VP 25 (1987): 210–24.Google Scholar

B87:7.Mermin, Dorothy. “Guide to Year's Work in Victorian Poetry: Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” VP 25 (1987): 207–10.Google Scholar

C. Biography, Criticism, and Miscellaneous

C87:1.Baly, Elaine. “The Poet's Last Residence: 29 de Vere Gardens.” BSN 16 (1986/1987): 14–16. ¶ Recently discovered unpublished letters and the floor plan of a similar house make it “possible to reconstruct something of the negotiations [RB] went through in acquiring” (14–15) his final residence.Google Scholar

C87:2.Beetz, Kirk H. “Three Themes in Browning's Gothic Satire ‘Mesmerism’.” Gothic ns 2 (1987): 6–15. ¶ More than simply an antioccult poem, “Mesmerism” combines Gothic images with the Pygmalion myth to satirize the Victorian ideal woman. Comparisons to Edgar Allan Poe and Mary Shelley.Google Scholar

C87:3.Bristow, Joseph. “Browning's Poetry of Poetry, 1833–64.” DAI 48 (1987): 51C. ¶ “[RB's] poetry attempts to represent its finite enshrinement of infinite, or divine, knowledge” (51C). Examines the development of this aesthetic in relation to Thomas Carlyle's early essays and to the radical Unitarianism of William J. Fox.Google Scholar

C87:4.Buckler, William E.Poetry and Truth in Robert Browning's The Ring and the Book. [See C85:9.]Google Scholar

C87:5.Byrd, Deborah. “Combating an Alien Tyranny: Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Evolution as a Feminist Poet.” BIS 15 (1987): 23–41. ¶ EBB's reading of and conversations with women writers, such as Letitia Landon, Fanny Kemble Butler and Caroline Norton, “furthered her development of a feminist consciousness and aesthetic” (24).Google Scholar

C87:6.Calcraft, Mairi. “Robert Browning's Pacchiarotto Volume: A Reinterpretation and Reassessment.” DAI 48 (1987): 52C. ¶ Suggests a reassessment of RB's Pacchiarotto, which would foreground RB's acceptance of fact as part of his poetic development.Google Scholar

C87:7.Christ, Carol. “The Feminine Subject in Victorian Poetry.” ELH 54 (1987): 385–401. ¶ Examines Victorian concern with “the gender of poetic sensibility” (385). “While [Alfred Lord] Tennyson repeatedly represents the danger of absorption in the female, [RB's] absorption of the lyric within the dramatic effectively contains the feminine” (396).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C87:8.Coggins, Paul E.Egoism versus Altruism in Browning's Dramas. Troy, MI: International Book Publishers, 1985. xiii + 130 pp. ¶ A reappraisal of Browning's dramas reveals their importance by looking at the conflict between characters' self-interest and concern for the social welfare of others. Includes chapters on Pippa Passes and In a Balcony.Google Scholar

C87:9.Coley, Betty A. “Done Into Doggerel.” SBHC 15 (1987): 55–70. ¶ Offers a detailed list of books from the Brownings' library which were recently acquired by the Armstrong Browning Library of Baylor University.Google Scholar

C87:10.Crowder, Ashby Bland. “The Elm-Tree as the Measure of a Life in The Inn Album.” BSN 16 (1986/1987): 10–14. ¶ “The Elder Woman's motives and character can best be comprehended in the image of the elm tree, which provides an understanding of her former self in relation to her present self” (10).Google Scholar

C87:11.David, Deirdre. Intellectual Women and Victorian Patriarchy: Harriet Martineau, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Eliot. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1987. xvi + 273 pp. ¶ Victorian intellectual women are “both resistant to and complicit with the culture that both encouraged and demeaned them” (xi). EBB specifically “wrote poetry about the power of female art and female sexuality” (24); yet she bears “firm identification with male modes of thought and aesthetic practice” (98). Aurora Leigh represents EBB's conservative political views and resulting sexual politics.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C87:12.Davis, Kris. “Browning's Caponsacchi: Stuck in the Gap.” VP 25 (1987): 57–66. ¶ Caponsacchi's dramatic situation, the frame narrative of his monologue, results from his passivity; during the monologue he becomes more aware of his isolation, not his salvation. Book vi demonstrates that gaps exist “'twixt what is, what should be,” 'twixt “great, just good God” and “miserable me” (ll. 487, 2105).Google Scholar

C87:13.Dedmond, Francis B. “Poe and the Brownings.” American Transcendental Quarterly ns 1 (1987): 111–22. ¶ Outlines Edgar Allan Poe's attempts to bring his writings to the attention of the Brownings, through correspondence with Poe's British contemporaries.Google Scholar

C87:14.Dooley, Allan C. “Epic and Anti-Epic in The Ring and the Book.” BIS 15 (1987): 137–50. ¶ Though deeply ironic, The Ring and the Book can be read as an authentic epic poem, with RB as its hero. Reader response to “a chain of associations and allusions that by nature depend on context and recollection” (140) helps to explain the poem's epic and non-epic features.Google Scholar

C87:15.Dupras, Joseph A. “Browning's Testament of His Devisings in The Ring and the Book.” VN 71 (1987): 27–31. ¶ In Books I and XII of The Ring and the Book, RB plays the subjective poet whose “counterfeit poetics” appears to explain everything for his readers while actually pointing out “our obtuseness and intellectual pride” (31).Google Scholar

C87:16.Dupras, Joseph A. “Fra Lippo Lippi, Browning's Naughty Hierophant.” BIS 15 (1987): 113–22. ¶ Although Lippo Lippi “gets himself off the hook” (120), RB charges his readers to work towards judging the painter's “inherent sacrilegeousness in his imagination and artistry” (114).Google Scholar

C87:17.Fish, Thomas E. “Questing for the ‘Base of Being’: The Role of Epiphany in Prince Hohenstiel-Schwangau.” VP 25 (1987): 27–43. ¶ In the opportunities for Action in Character that Hohenstiel experiences in his moments of epiphany, RB validates the human quest for “the base of being” – the truth of what one is and what one could/should be.Google Scholar

C87:18.Flowers, Betty S. “Virtual and Ideal Readers of Browning's ‘Pan and Luna’: The Drama in the Dramatic Idyl.” BIS 15 (1987): 151–60. ¶ “In the dramatic idyls, [RB] not only plays himself as Ideal Reader of the original text, but also asks his readers to play themselves as Audience to the dramatic reading of that text” (153). RB led the Victorian reader to appreciate the harmony implicity in his Georgic source.Google Scholar

C87:19.Garrett, John. “Other Victorians: Browning, Hopkins and Hardy.” British Poetry Since the Sixteenth Century. Totowa, NJ: Barnes and Noble Books, 1987. 161–84. ¶ RB's “secular interest” in the motives for human behavior separate his poetry from that of more conventional Victorian poets. Focuses mainly on “My Last Duchess” as a poem “already at the threshold of 20th-century artistic vision” (169).Google Scholar

C87:20.Gibson, Mary Ellis. History and the Prism of Art: Browning's Poetic Experiments. Columbus, OH: Ohio State UP, 1987. x + 341 pp. ¶ RB's view of history shapes his poetic forms. “The force of [RB's] poetry, and the legacy of historicism generally, compel the reader to consider himself or herself a historical individual attempting, through limitations, the interpretation of history” (6). In RB's poetry “historical materials give rise to a poetry of obstacles” (13), in which the poet presents the impossibility of unmediated knowledge. Focuses on Sordello, The Ring and the Book, and the historical monologues.Google Scholar

C87:21.Griffin, Susan M. “James's Revisions of ‘The Novel in The Ring and the Book’.” Modern Philology 85 (1987): 57–64. ¶ Henry James's sense of audience dictated revision of his essentially appreciative 1912 address for the Royal Society of Literature into a more theoretically critical essay for publication in a literary journal.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C87:22.Hatfield, Leonard L. “Speaking With Authority: Credibility and Authenticity in Browning's Men and Women and Yeats' Wild Swans at Coole.” DAI 47 (1987): 3047A. ¶ RB encourages judgments by readers before offering his authentic voice while William Butler Yeats promotes and undercuts the authority of a transcendental system. (Uses reader-response theory and narratology.)Google Scholar

C87:23.Jack, Ian. “Browning's Dramatic Lyrics (1842).” BIS 15 (1987): 161–75. ¶ Though the short poems of Dramatic Lyrics may appear fragmentary or non-sequential, the volume has unity and marks a change in RB's writing to a greater emphasis on the human soul.Google Scholar

C87:24.Karlin, Daniel. The Courtship of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett. [See C85:31.]Google Scholar

C87:25.Karlin, Daniel, and Woolford, John. Letter (“Browning Translations”). TLS 17 07 1987: 769.Google Scholar

Reply by Smith, Margaret M., TLS 14 08 1987: 875. ¶ The initial letter questions attribution often translations of Anacreon's poems to RB in the Yale edition of his poetry. The responses cite previous scholarship to concur that the poems should be attributed to EBB.Google Scholar

C87:26.Lang, Cecil Y. “Love Among the Ruins.” BIS 15 (1987): 1–22. ¶ Surveys the genesis and development of nineteenth-century romantic love literature. Includes examples from Aurora Leigh, “By the Fireside,” and Fifine at the Fair.Google Scholar

C87:27.Latané, David E. Jr. Browning's Sordello and the Aesthetics of Difficulty. Victoria, BC: English Literary Studies, University of Victoria, 1987. 147 pp. ¶ Sordello can best be understood as a “mature extension of the poetics of its time, as well as a late-Romantic attempt to write an epical work which must be read both willfully and imaginatively” (10). Placed in the context of the 1830s, the work bears affinities to Pippa Passes, also a work of the 1830s.Google Scholar

C87:28.LeFew, Penelope A. “A Note on Browning and Schopenhauer.” SBHC 15 (1987): 51–54. ¶ Because RB's knowledge of Arthur Schopenhauer came from secondary sourcs, RB was able to adapt Schopenhauer's pessimism into his own religious and poetic ideology.Google Scholar

C87:30.Loucks, James F. “The Bishop and Trimalchio Order Their Tombs.” SBHC 15 (1987): 35–40. ¶ Considers the possibility that RB used the “Trimalchio's Feast” section of Petronius's Satyricon as a source for “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed's Church.” The poem is “finally concerned … with the limits of temporal power and with the tragedy of misplaced faith” (40).Google Scholar

C87:31.MacLean, Kenneth. “Wild Man and Savage Believer: Caliban in Shakespeare and Browning.” VP 25 (1987): 1–16. ¶ A thorough understanding of RB's “Caliban Upon Setebos” is dependent on an understanding of how both RB's and Shakespeare's Caliban are symbolic figures drawn from the Wild Man archetype as Jungian “Shadow.”Google Scholar

C87:32.Martin, Loy D. Browning's Dramatic Monologues and the Post-Romantic Subject. [See C85:37.]Google Scholar

C87:33.Maynard, John. “Browning, Donne and the Triangulation of the Dramatic Monologue.” John Donne Journal 4 (1985): 253–67. ¶ The use of reader response theory reveals how RB's reading of John Donne was “a major force in helping [RB] to the new poetry of argument … that finds its best realization in the dramatic monologue” (258).Google Scholar

C87:34.Maynard, John. “Speaker, Listener, and Overhearer: The Reader in the Dramatic Poem.” BIS 15 (1987): 105–12. ¶ Details the relationship of the reader to dramatic monologue. During the responsive activity, a dialectical process of interpretation occurs. “A complex triangular rhetorical sighting” (III) determines the reader's position.Google Scholar

C87:35.Meredith, Michael. “A Botched Job: Publication of The Ring and the Book.” SBHC 15 (1987): 41–50. ¶ “The series of mischances which occurred during the publication of The Ring and the Book have wide ramifications for the bibliographer, the textual critic and the editor” (42–43).Google Scholar

C87:36.Miller, Louise M. “Browning's Virtue.” Explicator 46 (1987): 18–20. ¶ RB's appreciation of Antonio da Correggio's paintings indicates that RB may have used the term “Virtue” to refer to both the function of art and to personal virtue.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C87:37.Morlier, Margaret Mary. “Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Poetics of Passion.” DAI 47 (06 1987): 4399A. ¶ The metaphysical assumptions of EBB's poetics reveal that her moral vision is based on the cognition of empathy.Google Scholar

C87:38.Munich, Adrienne Auslander. “Robert Browning's Poetics of Appropriation.” BIS 15 (1987): 69–77. ¶ In Book One of The Ring and the Book, RB as the male poet “constructs his own myth about the ring out of culturally-received notions about the female Other” (69). RB appropriated the circle's semiotic association with the female, perhaps as a way of challenging EBB's poetics.Google Scholar

C87:39.Nichols, Ashton. “Browning's Modernism.” The Poetics of Epiphany: Nineteenth-Century Origins of the Modern Literary Moment. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: U of Alabama P, 1987: 107–43. ¶ Argues that an “‘epiphanic imagination’ underlies the moment of crisis and character revelation” (107–08) in RB's dramatic monologues, preparing the way for twentieth-century novelists. Looks at several monologues and devotes a section to The Ring and the Book.Google Scholar

C87:40.Perkins, Don. “‘Such a Heavy Mind’: The Performer's Burden in Robert Browning's ‘A Toccata of Galuppi's’.” Newsletter of the Victorian Studies Association of Western Canada 13 (1987): 43–45. Abstract of conference paper on RB's use of his musical education to create “verbal music” (43), specifically in “A Toccata of Galuppi's.”Google Scholar

C87:41.Pfordresher, John. “Chesterton on Browning's Grotesque.” English Language Notes 24.3 (03 1987): 42–51. ¶ In his criticism of RB, G.K. Chesterton uses John Ruskin's critical theories in order to respond tacitly to “a damaging attack by Walter Bagehot” (43).Google Scholar

C87:43.Posnock, Ross. “James, Browning and the Theatrical Self: The Wings of the Dove and In a Balcony.” Bucknell Review 30.2 (1987): 95–116. ¶ In 1902, Henry James rewrote RB's In a Balcony as The Wings of the Dove. “The most significant aspect of Henry James's remarkable appropriation of In a Balcony is his ‘rehandling,’ with his ‘own vision and understanding,’ of the ‘subject’ of theatricality” (96). The psychological needs of both authors dictated the conclusions of these works.Google Scholar

C87:44.Potkay, Adam. “The Problem of Identity and the Grounds for Judgment in The Ring and the Book.” VP 25 (1987): 143–57. ¶ No infallible center of authority exists in The Ring and the Book because no character has an unproblematic identity.Google Scholar

C87:45.Purdy, Richard. “Robert Browning and André Victor Amédée de Ripert-Monclar: An Early Friendship.” Yale University Library Gazette 61 (1987): 143–53. ¶ Recently revised by Philip Kelley, Purdy's 1945 article examines the friendship and correspondence of RB and Monclar as a possible influence on RB's Paracelsus.Google Scholar

C87:46.Richardson, Joanna. The Brownings: A Biography Compiled from Contemporary Sources. London: London Folio Society, 1986. xv + 285 pp. ¶ Primarily “the account of a unique relationship between two poets: of the meeting between [RB] and [EBB], of their instant and extraordinary love for one another, and of the private marriage which was publicly recognized as one of the happiest in literary history” (xi). Critically privileges the work of RB over EBB.Google Scholar

C87:47.Rudoe, Judy. “Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the Taste for Archaeological Style Jewelry.” Bulletin of the Philadelphia Museum of Art 83 (1986): 22–32. ¶ Traces the history of the gold mosaic brooch, now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which was worn by EBB for the Gordigiani portrait, now hanging in the National Portrait Gallery, London.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C87:48.Ryals, Clyde de L.Becoming Browning: The Poems and Plays of Robert Browning 1833–1846. [See C83: 58.]Google Scholar

C87:49.Ryals, Clyde de L. “Levity's Rainbow: Browning's ‘Christmas-Eve’.” Journal of Narrative Technique 17 (Winter 1987): 39–44. ¶ In “Christmas-Eve,” RB used “narrative informed by levity” (40) to write a poem that deconstructs its examination of sectarian religion.Google Scholar

C87:50.Schweik, Robert C. “Art, Mortality, and the Drama of Subjective Responses in ‘A Toccata of Galuppi's’.” BIS 15 (1987): 131–36. ¶ In “A Toccata of Galuppi's,” RB “dramatized one speaker's changing subjective reactions to Galuppi's music so as to present the relationship of art to mortality in remarkably diverse perspectives” (132).Google Scholar

C87:51.Schwiebert, John E. “Meter, Form and Sound Patterning in Robert Browning's ‘A Toccata of Galuppi's’.” SBHC 15 (1987): 11–23. ¶ Critics who only analyze what the poem says about the art of music “tend to slight the art of words in the poem” (11). Examining versification and sound patterns can demonstrate the unity of the poem's various themes.Google Scholar

C87:52.Shaw, W. David. The Lucid Veil: Poetic Truth in the Victorian Age. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1987: xix + 311 pp. ¶ Looks at the connection between Victorian poetics and changing theories of language and knowledge. Treats RB throughout, especially as he “uses and challenges [David Friedrich Strauss'] methods of scientific historiography” (56), Friedrich Schleiermacher's “theology of dependence,” Benjamin Jowett's “liberal hermeneutics,” and G.W.F. Hegel's concept of the double Trinity.Google Scholar

C87:53.Stephenson, Glennis. “‘Bertha in the Lane’: Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the Dramatic Monologue.” BSN 16 (1986/1987): 3–9. ¶ Previous critics of “Bertha in the Lane,” who judged the poem sentimental, based their readings on a surface text. A subtextual reading suggests that EBB used dramatic monologue to reveal “the repressed desires of an apparently dutiful and loving girl” (8).Google Scholar

C87:54.Stephenson, Glennis. “Women and Love in Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Aurora Leigh.” Newsletter of the Victorian Studies Association of Western Canada 13.1 (1987): 46–48. Abstract of conference paper on the “maligned love story” of Aurora Leigh, tracing Aurora's growth toward “redefinition and acceptance of the nature of women and love” (46).Google Scholar

C87:55.Stone, Marjorie. “Genre Subversion and Gender Inversion: The Princess and Aurora Leigh.” VP 25 (1987): 101–27. ¶ An example of what Mikhail Bakhtin calls the “novelized epic,” Aurora Leigh is more polyglot than Alfred Lord Tennyson's poem. In both works, the subversion of genre differences facilitates and reinforces the questioning of gender distinctions.Google Scholar

C87:56.Sullivan, Mary Rose. “‘Some Interchange of Grace’: ‘Saul’ and Sonnets from the Portuguese.” BIS 15 (1987): 55–68. ¶ Details the poetic interaction between EBB and RB during their composition of Sonnets from the Portuguese and “Saul,” and suggests that this “‘transference of energy’” (66) affected their later longer works.Google Scholar

C87:57.Sutphin, Christine. “Revising Old Scripts: The Fusion of Independence and Intimacy in Aurora Leigh.” BIS 15 (1987): 43–54. ¶ Using the psychological premise posed by Carol Gilligan, Sutphin proposes that, veiwed in a mid-nineteenth-century context, the ending of Aurora Leigh is radical, “not only because the heroine asserts herself as an artist, but because she questions the long-accepted opposition between independence and care for others” (44).Google Scholar

C87:58.Tucker, Herbert F. “Robert Browning: Ulterior Reality, Penultimate Meaning, Existential Ultimatum,” Ultimate Reality and Meaning 10 (1987): 202–13. ¶ By inverting stage conventions, RB's dramatic monologue “shaped and constrained [the speaker's] ostensibly autonomous utterance, and provided the reader with grounds for an independent judgment not at all congruent with the speaker's: a poetic equivalent of dramatic irony” (203).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C87:59.Turner, W. Craig. “Art, Artist, and Audience in ‘A Toccata of Galuppi's’.” BIS 15 (1987): 123–29. ¶ “Through layering, [RB] has faithfully and ironically portrayed both the ability of the artist to convey universal truth and the difficulties that audiences have in feeling and accepting … the mortality of people in all historical contexts and from all philosophical perspectives” (129).Google Scholar

C87:60.Turner, W. Craig. “Browning, ‘Childe Roland,’ and the Whole Poet.” South Central Review 4 (1987): 40–52. ¶ A biographical reading that can complement other studies of the poem. “One of its more rewarding readings is as the subconscious soul-searching of the no longer young poet who feels that he has not yet achieved the successful maturity of knighthood, but who recognizes the importance of his quest” (51).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

C87:61.Walsh, Thomas P. “‘All's Right With the World’: Pippa's Enthymeme.” SBHC 15 (1987): 24–34. ¶ “Pippa Passes provides a possible way in which to fuse the ideal with the real and to provide a social function which will not inhibit or contaminate the role of poet-prophet-priest” (26).Google Scholar

C87:62.Weissman, Judith. “Women Without Meaning: Browning's Feminism.” Midwest Quarterly 23 (1982): 200–14. ¶ RB “departs radically from poetic tradition by refusing to bestow meaning on his women… [RB's] women, in comparison with those created by other poets, have an untouchable existence, a mysterious independence” (201). Through this new woman, RB “finds a new value in his poetry – the comfort of transformed, shared suffering” (214).Google Scholar

C87:63.White, Leslie. “‘Uproar in the Echo’: Browning's Vitalist Beginnings.” BIS 15 (1987): 91–103. ¶ RB's conception of vitalism differed from Arthur Schopenhauer's Will. RB saw the individual human will as an intuitive impulse, “and as a means to realize the self and locate its place in the world” (91). Pauline, Paracelsus, and Sordello disclose the form RB's vitalism assumes.Google Scholar

C87:64.Woolford, John. Browning the Revisionary. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1987. 224 pp. ¶ RB's intention of selling his work “like any other trader … produced self-revision, as the practical application of his revision of Romantic aesthetics” (ix). With a principle of the “structured collection,” RB revised Men and Women, unified Dramatis Personae and achieved great popularity with The Ring and the Book. Use of Thomas Carlyle, John Stuart Mill and other contemporary commentators and reviewers.Google Scholar

C87:65.York, Lorraine. “The Rival Bards: Alice Munro's ‘Lives of Girls and Women’ and Victorian Poetry.” Canadian Literature 112 (1987): 221–16. ¶ In her 1971 novel Lives of Girls and Women, Alice Munro “has dealt with a clash between mother and daughter, tradition and innovation, by associating it with the earlier clash of sensibilities between the two rival bards of the Victorian age” (211), Alfred Lord Tennyson and RB respectively.Google Scholar

C87:66.Zietlow, Paul. “The Ascending Concerns of The Ring and the Book: Reality, Moral Vision, and Salvation.” Studies in Philology 84.2 (1987): 194–218. ¶ Poem “tests the reader's readiness for salvation” (194), by forcing the reader to witness and experience “internal rebirth and resurrection” (195). “The poem must be seen as an effort of religious renewal exerted in an age perceived to be materialistic and faithless” (218).Google Scholar