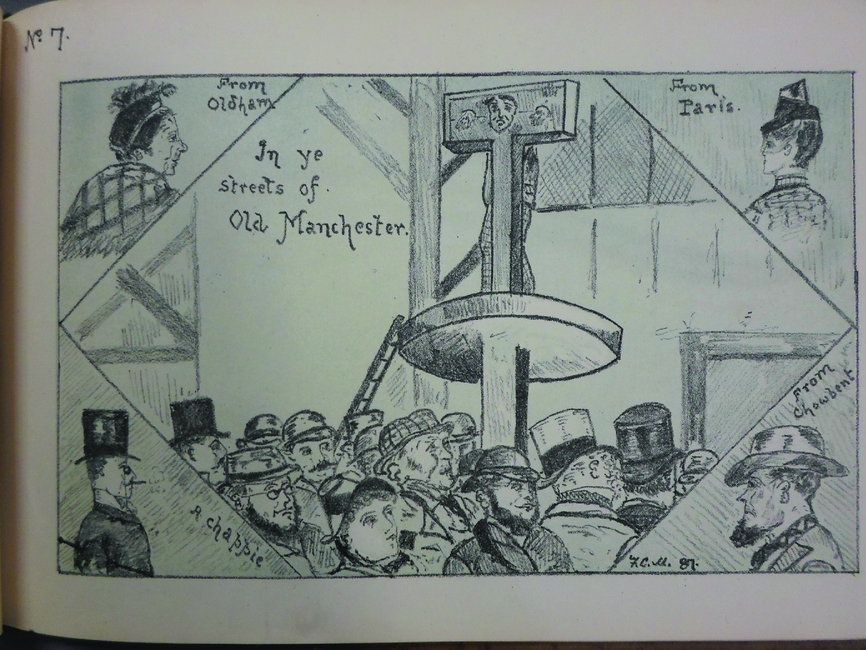

At the 1887 Royal Jubilee Exhibition in Manchester, one of the most popular attractions was Old (sometimes referred to as Olde) Manchester and Salford, a reconstructed set of streets and alleys representing historic aspects of Manchester and Salford. People We Met at the Manchester Exhibition, a booklet sold for 1s at the exhibition, containing hand-drawn sketches and caricatures of visitors and others, by ‘Marksman’, reveals a vibrant and diverse crowd of visitors, enjoying the spectacle of each other as well as interacting with costumed staff and with the physical spaces of the street (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 The understanding of urban history and heritage emerging from the reconstructed urban streets and districts appearing at international and national exhibitions between 1884 and 1908 was complex and, in many ways, innovative.Footnote 2 Such reconstructions were both scholarly and popular; gave weight to both buildings and the people who had populated them; and moved between national and local understandings of the past. The people behind them came from a range of backgrounds, including amateur local history, architecture, commerce and entertainment. Moreover they were exceptionally popular attractions, and evidence from photographs, drawings and newspaper coverage suggests that the substantial number of staff working there, and the crowds of visitors, were important actors in the development of the meanings of such historic attractions. My contention in this article, therefore, is that while such commercial versions of urban heritage were linked to ‘official’ versions of urban heritage through their personnel, they also incorporated a wider range of people and expertise, and their meaning emerged not simply through authoritative historical discourses, but through the performances, interactions and bodily experiences of workers and visitors to the streets. They reveal modern urban memory practices responding to changing urban environments by prioritizing embodied, performative and haptic ways of encountering and interpreting the past.Footnote 3

Figure 1: From ‘Marksman’, People We Met at the Exhibition (Manchester, 1887) (Trafford Local Studies TRA453), no. 7. Image courtesy of Trafford Local Studies.

Historic urban reconstructions at exhibitions: the development of a genre

Between 1884 and 1908, there were over 10 reconstructions of historic urban streets or quarters at national and international exhibitions. The first was staged at the International Health Exhibition in London in 1884, and subsequently also formed part of the Inventions Exhibition of 1885 and the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886. Meanwhile, Old Antwerp was recreated at the Antwerp Exhibition of 1885. Old Edinburgh formed part of the Scottish International Exhibition in Edinburgh in 1886, while Old Manchester and Salford featured in the Royal Jubilee Exhibition in Manchester in 1887, and a small reconstruction of the Old Tyne Bridge was included in the Newcastle Exhibition of the same year. There was another Old Antwerp at the Antwerp Exhibition of 1894, followed by the huge Alt-Berlin at Berlin's Industrial Exposition of 1896. Gamla Stockholm, at the 1897 Stockholm Exhibition, followed Old Buda at the Millennium Exhibition in Budapest in 1896, while ‘Old Brussels’ was also staged in 1897. The apex of the phenomenon was probably reached in 1900 with Albert Robida's spectacular Vieux Paris, with probably 50 million visitors.Footnote 4 By the time of the Franco-British Exhibition in London in 1908, the Old London Street was accorded only a very brief mention at the end of the official guidebook, with the Flip Flap, an innovative fairground ride, and the Senegalese and Irish villages all attracting far more attention.Footnote 5 By 1908, of course, Britain at least was in the grip of ‘pageant fever’ and arguably appetites for spectacular stagings of urban pasts were more fully sated by those intensely participatory events than by increasingly indistinguishable historic streets.Footnote 6

Not only did these historical urban reconstructions all take place within a relatively short time frame, they borrowed from and competed against each other, which resulted in the paradoxical fact that displays intended to celebrate national and regional specificity ended up sharing many generic features.Footnote 7 This was also partly a function of the need to fit a considerable number of historical buildings and features into a small space, and give the impression of an entire city. Among these generic features were craft demonstrations, staff in historic costumes and stocks, pillories, fountains, wells and other items of street furniture, which were always very popular with visitors. The similarities between the 1884 Old London (Figure 2) and Old Manchester and Salford (Figure 3) are particularly striking, and a figure can be seen in the stocks outside the Old London exhibit of 1908 in Figure 4.

Figure 2: Photograph: the International Health Exhibition at South Kensington: reproduction of London in the Olden Time. © Look and Learn/Peter Jackson Collection.

Figure 3: View of Old Manchester and Salford at the Royal Jubilee Exhibition, Manchester, 1887. Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives GB127.m61894. Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Council.

Figure 4: Postcard: exterior of Old London exhibit at the Franco-British Exhibition, 1908. Author's own collection.

While the significance of exhibition displays in creating new forms of rural heritage and museum has been acknowledged, the role of these popular and widely staged, if ephemeral, old streets in shaping the understanding of urban heritage has not been explored.Footnote 8 Rather, coverage of the early development of urban heritage has focused on the ways in which, following William Morris’ ‘anti-scrape’ campaign, an elite, architect-led, building-focused type of heritage arose which concentrated on ‘saving’ nationally important monuments, either from destruction or from invasive restoration.Footnote 9 A prominent example of the focus on elite buildings in the development of heritage around 1900 can be found in the work of Laurajane Smith. She argues that this period saw the emergence of the ‘authorised heritage discourse’ (AHD), a way of using the past to naturalize elite cultural values and render other (subaltern or unauthorized) ideas about the past illegitimate.Footnote 10 Simultaneously, this process gave rise to and authority to heritage professionals, whose apparent ‘specialist’ status and knowledge allowed them to make ‘objective’ decisions about heritage practice and policy.Footnote 11 Thus, heritage emerged focusing on the tangible, especially authentic historic fabrics, the monumental and the national, and delegitimizing the intangible, the local and the small-scale, the insufficiently ancient and that without provenance.Footnote 12 Smith also asserts that much of the early concern of ‘heritage’ proponents was for rural environments and buildings, partly as a reaction to modern urban growth, but also because churches and country houses were expressions of elite culture.Footnote 13

In many ways, then, Smith's articulation of the growth of an AHD would suggest that the reconstructed urban streets of the exhibitions were most definitely unauthorized and increasingly illegitimate in a period when ‘proper’ heritage was being forged. The streets were urban, unevenly monumental, invariably on a smaller-than-life scale, often foregrounded local or regional history over the nation, and apparently worked on a very different understanding of ‘authenticity’ from that of William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.Footnote 14 However, such a dichotomizing approach fails to appreciate the many links and overlaps between what Smith sees as ‘authorised’ and unauthorized approaches, which in fact shared personnel and expertise which was not solely architectural and archaeological, engaged with similar problems, and showed diverse but not opposed understandings of concepts of significance and authenticity, understandings which were brought into dialogue by attractions such as the streets. If heritage is a process rather than a set of objects, then the history of heritage has tended to neglect the ways in which a wide range of actors negotiated that process, and in particular has paid less attention to urban heritage and to heavily commodified sites as offering an arena for dialogic processes.Footnote 15

Far from grand narratives of nation-state and aristocracy, across a range of different historical genres popular interest in the everyday past made itself felt.Footnote 16 Moreover, the fin de siècle period can be seen as one where a wide range of new memory practices were being tried out, as technological and social change radically altered the relationship between people and the past in a productive as well as destructive way; commercialization and commodification were an important part of this change.Footnote 17 One of the effects of such change was that a new concern with the experiential, affective and haptic, stemming from modernity, was added to existing popular interests in the past. To investigate this, I draw on work by Michel de Certeau and Alison Landsberg, who explore, respectively, how ‘everyday’ practices such as walking through the city formed collective memories in opposition to official town planning which stripped out historical references from the urban environment, and how new media offered opportunities for embodied adoption of ‘memories’ by those who had no direct connection with the event represented, ‘re-rooting’ them, essentially, in the face of modernity's dislocations.Footnote 18

By recuperating the exhibitions’ historic streets as part of the growth of urban heritage, we can see that the audience and workers always made a significant contribution to the understanding of the urban past, co-producing ideas about authenticity and historical experience. Again, de Certeau offers a model for how we can think about the active contribution of these groups to the work that heritage attractions did, through his insistence on the way that moving through a space – ‘the act of passing by’ – constitutes an interpretation of that space. Thus, the experiential and embodied nature of people's engagement with an apparently hegemonic form means that such a form's meaning is only created by that encounter, rather than determined in advance.

In order to investigate the whole range of contributors to such heritage attractions, we need to think about the source material available. Exhibitions have produced varied and rich records, but of particular interest here are those which can tell us about the production and consumption of meaning in the streets by various actors, some of whom are easier to access than others. ‘Official’ producers – designers, historian consultants and officials from local government – tended to leave quite explicit material in programmes, souvenirs, maps, plans and speeches outlining what they saw as the rationale and meaning of the constructions.Footnote 19 Visitors, while leaving less explicit traces in the records, can be partly understood through descriptions of the crowds at the exhibitions. These descriptions do not provide evidence of interpretation and meaning making in the same way as for the streets’ creators, because they do not generally record verbal accounts by visitors of their understandings, although sources such as newspaper accounts do record the reporter's inferences about visitors’ reactions. However, they can tell us something about how visitors behaved: where the crowds were, whether people appeared to be enjoying themselves or not, what they were actually doing. Although such descriptions were undoubtedly filtered through reporters’ interpretations and expectations of visitor behaviour, especially for visitors from the working classes, material giving us information about visitors has been under-used in previous studies of historic street reconstructions. I am particularly interested in sources which depict visitors – photographs and drawings – although these present problems of their own. A writer in the Manchester Guardian asserted that photographs of visitors to the exhibition were being touched up, so that ‘a wrinkled dame of sixty is made to come out with a face as plump as a girl of eighteen!’.Footnote 20 Meanwhile, in hand-drawn depictions of visitors which tend to have humorous or satirical intent, there is almost rather a focus on the grotesque aspects of the crowds.Footnote 21 Thus, idealization and mockery of visitors are both present.

Workers at the exhibitions, however, are the hardest to research. As I show below, people employed on the old streets undertook a variety of roles from acting out small vignettes, to providing historical colour by ‘peopling’ the streets, to demonstrating historical craft processes, to merely serving in shops and cafes; all wore historical costume and were to a greater or lesser extent performing a role. As Qureshi has suggested for a different group, those working in ‘ethnic’ villages, newspaper accounts can capture interaction between visitors and performers or workers, offering ‘glimpses’ of an otherwise hard to see group.Footnote 22 This article, then, focuses on uncovering ideas, performances, behaviours and encounters which triangulate the meanings of the old streets; and finds evidence of these largely in programmes, newspaper coverage and other representations of the streets in use. The depictions by ‘Marksman’ are of particular interest, along with those of J.S. Smith in his similar Exhibition Sketches booklet, sold for only a penny, as showing a local, humorous account devoted particularly to incongruity, which offers a notably different perspective to the overly polished accounts to be found elsewhere.Footnote 23 As a result, I focus on the British streets, especially Old London (1880s and 1908 versions) and Old Manchester and Salford, with occasional references to the wider European examples.

People, co-production and the nature of expertise

Although it has been suggested that the fin de siècle period saw the rise of the heritage expert and the concomitant narrowing of what might count as heritage, looked at from another perspective a very wide range of ‘expertise’ was accepted, and a variety of people were involved in the development of urban heritage. In the exhibitions, old streets were created by a combination of architects, local history amateurs and professional impresarios, with some local government involvement and oversight. Arguably, the man with the most legitimate expertise in urban heritage was George Birch, the man behind the Old London Street at the Sanitary Exhibition of 1884. He was an architect and antiquarian who later became director of the Soane Museum in London.Footnote 24 Similarly, Old Edinburgh was designed by Sydney Mitchell, another antiquarian and architect, though younger than Birch; but it was also shaped by J.C. Dunlop, a councillor, and his sister, Alison Hay Dunlop, a local historian, who wrote the accompanying Book of Old Edinburgh, which as Wilson Smith argues, turned the street into a Liberal and Presbyterian vision of the particular role of Edinburgh in the development of the Scottish nation.Footnote 25 In Manchester, Alan Kidd has noted how strongly rooted the production of Old Manchester and Salford was in the amateur local history societies of the region.Footnote 26 Alfred Darbyshire, the designer, was an architect but as someone who designed theatres, created spectacular stage sets, was friendly with leading actors and acted in plays on an amateur basis, he brought a strong theatrical sensibility to the staging of the past.Footnote 27 This element of showmanship came further to the fore over time, and by 1900 and after, both Albert Robida in Paris and Imre Kiralfy in London were bringing a much more spectacular and theatrical flavour to their historical recreations.Footnote 28 This was not, though, necessarily in opposition to the local historical approach as Robida, at least, had as much historical knowledge as many of his predecessors. However, those who designed and wrote about the streets were not the only ones who could be considered to have made them. I also want to include here two other groups of people: those who worked in the streets and those who visited them.

Staff: Performing urban history

To take the workers first, it is clear that these were very important to the success of the attractions. Nearly all the streets featured people in costume ‘peopling’ the streets, staffing shops, demonstrating historical processes such as hand printing and selling ‘historic’ products or souvenirs, or running cafes, restaurants and other food and drink outlets; these latter often women. The absence of such commercial activities was one of the reasons why Old London increasingly declined in popularity.Footnote 29 At the Royal Jubilee Exhibition in Manchester where Old Manchester and Salford was staged, absolutely no on-site selling was allowed except for goods which had been made on the premises, which effectively meant that only the historical crafts and other goods made in situ in the old town area were available to buy, giving an added importance to the workers who demonstrated such historical processes, and considerable attractiveness to renting space in Old Manchester and Salford.Footnote 30 There were, additionally, costumed staff whose job was not to sell things but to act as attendants and add to the ambience of the street; at Old Manchester and Salford there were figures including town guards from a number of eras (see Figure 5). These were not, in Britain, actors; however, other historical urban reconstructions such as Gamla Stockholm and Vieux Paris did employ actors, in Stockholm performing set piece incidents, and in Paris apparently trained to speak in Old French to add sound to the historical features of the place.Footnote 31 The staging of postcard views suggests a certain amount of self-conscious performance at Old London (Figure 4).

Figure 5: Photograph showing range of costumed staff working at Old Manchester and Salford in 1887. Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives GB127.m61879. Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Council.

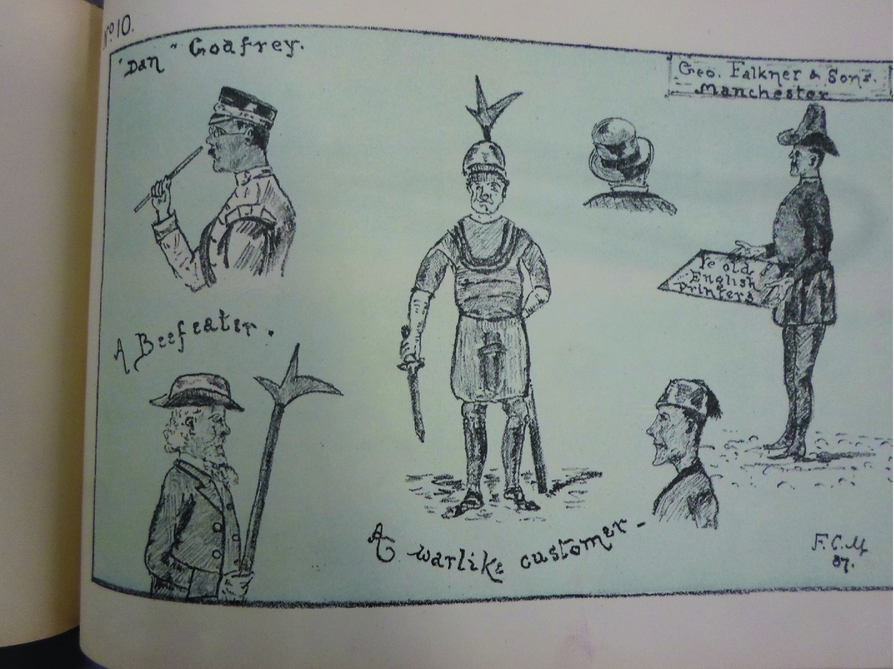

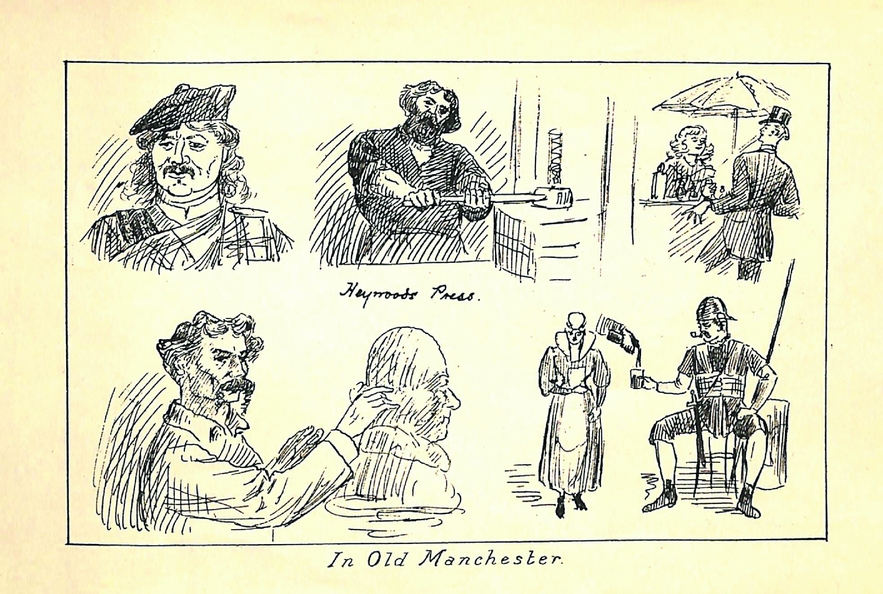

There are few sources to give us much information about such staff; in some places, they were predominantly young and female. At Alt-Berlin where over half the concessions were for food and drink, it was alleged that the women serving at the inns and cafes were turning to prostitution because the low level of visitors to the exhibition initially meant that their wages and tips were unsustainably low.Footnote 32 By contrast, at other exhibitions, visual evidence suggests the streets were peopled in a much more ‘masculine’ way; the balance is definitely towards men in Figure 5, showing some staff from Old Manchester and Salford. The strong presence of guards and sentries suggested a past full of masculine violence, though this had to be managed to maintain the entertaining nature of the venue: the ‘Marksman’ caricature of the ‘warlike customer’ made such figures safe by gently mocking them (Figure 6). Additionally, it was occasionally asserted that the ‘warders’ were keeping the exhibit safe from theft and damage.Footnote 33 Sometimes, the staff were criticized and seen as shattering the illusion; of Old Edinburgh, The Times’ correspondent said ‘There is not much that can be called antique . . . in the style and conduct of the attendants’; but whether such criticism was widely felt is unclear.Footnote 34 ‘Penelope’, who wrote a ‘Ladies’ column’ which was carried in a number of provincial newspapers, described an encounter in Old Manchester with two ‘brawny Scotsmen’ guarding a building which was supposed to contain Bonnie Prince Charlie; an image of one ‘Scotsman’ character can be seen in Figure 7. She discovered that one of them at least was actually Irish and seemed to make no attempt to stay in character, but she did not express any criticism of this illusion breaking; convincing costume seemed to be more important to her than role play.Footnote 35 A positive enjoyment of incongruity and anachronism among staff is suggested by the inclusion in Figure 7 of a ‘Roman soldier’ off duty, sporting a rather Victorian moustache, a pipe and apparently being poured a glass of beer. The costumed staff played a key role in making the historical streets believable and entertaining for visitors, and were active agents in the performance of their parts, especially as in most cases there were no ‘set pieces’ for them to perform. These employees, of course, were in a better position to retain autonomous agency than those people who performed their own ethnicity in ‘colonial villages’ at the exhibitions; the former were acknowledged to be playing parts rather than displaying their inherent identities, as the reactions to anachronism show, and people from the past were anyway much less likely to be seen as ‘primitive’ than people from colonial areas.Footnote 36

Figure 6: From ‘Marksman’, People We Met at the Exhibition (Manchester, 1887) (Trafford Local Studies TRA453), no. 10. Image courtesy of Trafford Local Studies.

Figure 7: From J.S. Smith, Exhibition Sketches (Manchester, 1887) (Trafford Local Studies TRA453), ‘In Old Manchester’. Image courtesy of Trafford Local Studies.

The businesses which rented space to demonstrate and sell products in Old Manchester and Salford were varied and not always historically appropriate; there were a couple of printers, a couple of textile businesses demonstrating handloom weaving and other hand techniques, quite a few jewellers and watchmakers, as well as a confectioner, a tobacconist and a wigmaker, along with representatives from Manchester Chief Fire Station.Footnote 37 Some of the firms, such as the printers, Heywood and Co., were known for bosses interested in local history, though this was far from universal (Figure 7 includes an image of Heywood's hand press in action).Footnote 38 There were strong expectations that workers with specific craft processes to demonstrate would make explicit haptic qualities such as deftness and speed, as well as performing ethnic, national or regional qualities which seemed to be an inherent part of the craft process: there were press references to Welsh women's spinning wheels, and to other workers being ‘dapper’ and ‘quick-handed’.Footnote 39 Male workers exhibited strength and manual prowess. The blacksmith at Old London in 1884 was depicted by the Illustrated London News being observed by a fashionable lady, whose physique, cleanliness and attire was emphasized through the contrast with the dark, shabby figure of the worker; the image was captioned ‘Venus and Vulcan’ (see Figure 8). Workers also encouraged visitors to get involved in the activities of the street, helping them into and out of the stocks and pillories, for example (see Figure 9).

Figure 8: ‘The International Health Exhibition, sketches of antique costume and of ancient London’, Illustrated London News, 2 Aug. 1884. Newspaper Image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.BritishNewspaperArchive.co.uk).

Figure 9: From ‘Marksman’, People We Met at the Exhibition (Manchester, 1887) (Trafford Local Studies TRA453), no. 8. Image courtesy of Trafford Local Studies.

Although we can understand the performances and representations of workers, finding evidence of their own motivations and experiences is much harder. One brief and in no way representative glimpse of them as a distinct group comes from a dispute recorded in local newspapers. About 300 workers, described as ‘attendants in the employ of the exhibitors’, walked out of the Manchester Jubilee Exhibition because of issues around their refreshment. They objected to the prices they were charged in the food outlets, the lack of dedicated facilities they had and the short time they had for lunch and other breaks. At one o'clock, they all left the exhibition site and went to get meals at locations outside. They refused to return to work on the next two days; thereafter, the committee agreed to provide these workers with a room of their own for refreshments, which would have hot water for tea-making.Footnote 40 Such a successful assertion of rights seems in contrast to those peopling the colonial villages, where, as Geppert shows, fairly exploitative contracts were in use and the ‘natives’ were not in a position to contest them.Footnote 41 How far the striking Manchester workers included those who peopled Old Manchester and Salford is not clear; in places, there is reference to all those who exhibited or assisted exhibitors, while in other places, the articles seem to refer only to those who worked in the machinery halls. Certainly it seems likely that the workers referred to here were male, and the status and assertiveness of female workers seems to have been lower, expected as they were to embody historical feminine ‘maidenly’ virtues.Footnote 42 We could suggest, therefore, that the agency of workers in the historical streets was structured by a range of issues including the level of specialized skills or performance they were hired for, their gender and ethnicity and the extent to which they were already employees of an exhibitor, carrying out their usual jobs but in historic costume and in public.

Visitors: experiencing urban history

Another key group to consider in an attempt to characterize the reconstructed streets in terms of the co-production of meaning is visitors. We have little information about individual visitors but we can draw some conclusions about how they contributed to the heritage process. In most cases, the historic streets were among the most popular attractions at the whole exhibition and were positively crowded for much of the opening period, and people moved around them in particular ways, which can be related to ideas about how people moved around the increasingly modern cities where the exhibitions were held.Footnote 43 As Qureshi has suggested, throughout the nineteenth century urban populations were learning and developing certain forms of spectatorship which gave them the tools to extract pleasure and meaning from leisured movement around the city.Footnote 44 Urban spectatorship as described by Qureshi was about the development of behaviour to deal with new urban environments – crowded streets, anonymous crowds, ephemeral encounters – and while visitors brought these skills to the reconstructed streets, these environments also offered an opportunity to experience pre-modern modes of street behaviour in a multisensory way. This is suggested by the staging of the streets so as to encourage slower and less purposive walking without grand vistas, with dead ends and curving alleys, and an emphasis on the novel feeling of walking on cobblestones.Footnote 45

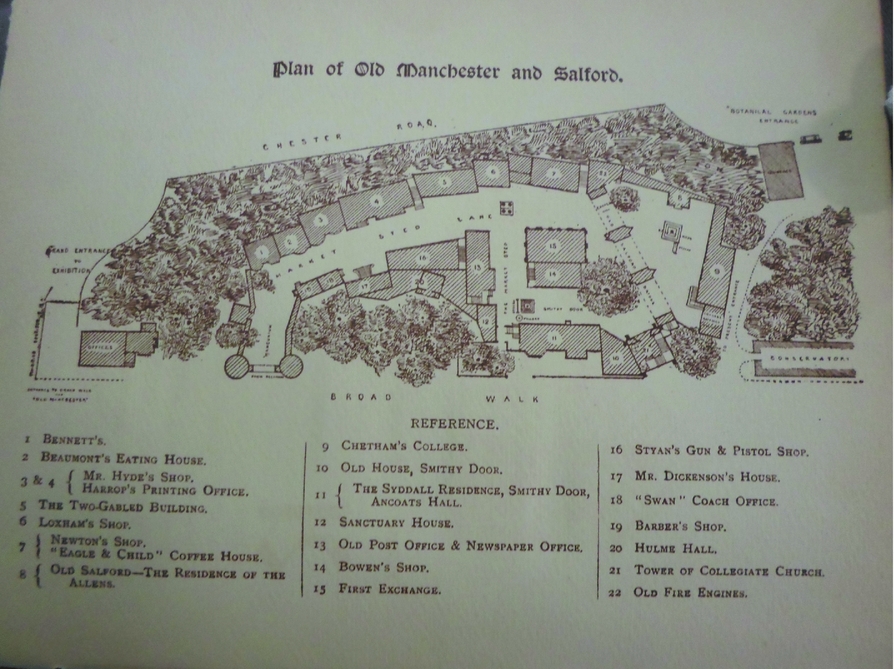

De Certeau's ideas, developed in the context of everyday resistance to the power of planning, are not always directly applicable to these streets, but do provide some tools which can help us conceptualize what happened when people visited these sites more fully. In de Certeau's analysis, the planning of the modern city is the expression of an objective rationality, focusing on system, efficiency and progress. However, the planners of the reconstructed streets (not, of course, town planners in the increasingly professional sense of the word) actively tried to instantiate an irrational plan imitating what they saw as the ‘quaint’ aesthetic of pre-modern urban environments and the ‘sinuosity’ of their streets (see Figure 10); a tactic which also served to make the small areas seem more substantial.Footnote 46 Moreover, the streets could be quite poorly lit to enhance this quaint character; for example, a ‘moonlight’ effect was aimed at in Old London.Footnote 47 In addition, as the areas were so small, maps of the streets and quarters did not serve to rationalize space in the way identified by de Certeau; rather, maps served to try and pin down the meaning of the street. Essentially, the old streets were small and easy to navigate, so maps or plans, which were widely included in souvenir guidebooks and handbooks, were directed towards framing the area as ‘picturesque’ and ensuring that visitors did not miss key attractions (Figure 10). Guidebooks and handbooks aimed to link buildings, monuments and spaces to particular stories; to re-attach historical memories to urban materiality, including both actual memories and older traditions and stories. Darbyshire recorded his memories of vanished Manchester landmarks in his Olde Manchester and Salford guide, while the Catalogue of the Health Exhibition said of one large building that it was connected, in an unspecified but largely speculative way, ‘with Sir Richard Whittington, famous in song and in story’.Footnote 48 De Certeau, on the other hand, describes the processes of modernizing urban environments, and particularly mapping them, as sundering such attachments.Footnote 49 One could, therefore, refine the processes of modernity de Certeau describes, as not so much removing memory from the urban environment, as assigning memory a specific and ephemeral site within the city, a site moreover concerned with popular entertainment.

Figure 10: Plan of Old Manchester and Salford, from Alfred Darbyshire (ed.), A Booke of Olde Manchester and Salford (Manchester, 1887).

Figure 11: Photograph showing people in costume and modern dress in the stocks at Old Manchester and Salford, 1887. Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives GB127.m61878. Courtesy of Manchester Libraries, Information and Archives, Manchester City Council.

The strategies of planning are certainly different, but what of the tactics of visitors to the historic street? By considering ‘the act itself of passing by’, an act which for de Certeau is structured by the rhythm of how people paused, gathered and looked from one place to another, visitors’ interpretation of the streets’ meaning becomes clearer.Footnote 50 Visitors’ movements can, to an extent, be reconstructed from sources like People We Met at the Manchester Exhibition, where visitors invent spaces by stopping and gathering at particular points, even if only because of a recalcitrant child (Figure 9). The points where crowds most clearly lingered were around stocks and pillories, and demonstrations of craft processes; these are also features of the streets which were heavily reported on.Footnote 51 Thus, a handbook to the Franco-British Exhibition of 1908 said of the Old London exhibit, ‘The most popular feature . . . was the man in costume . . . who passed doleful days with his feet fixed in stocks’, going on to say ‘He, too, sold postcards’ (see Figure 4).Footnote 52 People gathered and paused by stocks and pillories, suggesting that public punishment was the most compelling element of the historical urban in their minds. ‘Marksman’ indicates in Figure 9 (as well as Figure 1) that visitors not only looked at the stocks and pillories in Manchester but could try them out themselves, and when they did so this became something for the other visitors to look at. Playing at being in the stocks was popular; at least one of the men in the stocks in Figure 11 was a member of the audience.Footnote 53 In an illustration of the 1884 Old London, male figures put their female companions into both the stocks and the pillory, suggesting an interest in the gendering of historical punishment which was echoed in newspaper discussions of the different ‘olden time’ punishments of men and women, including the ducking stool as a punishment for females only (though there is no evidence that ducking stools were part of any of these streets) (see Figure 8).Footnote 54 As Melman has suggested for the Tower of London, there were definite signs that historic physical punishment of women formed a compelling spectacle for late nineteenth-century visitors, and that ‘punishment and victimhood came to be identified with women’.Footnote 55 Men were interested in occupying stocks and pillories as well, but the spectacle of women having the punishments enacted on them seemed even more compelling.

Along with enactment of physical punishment, visitors crowded around demonstrations of craft processes. They stopped to watch people making things by hand both in the historic recreations and at other places within the exhibitions, as this quotation from The Times about Old London shows.

Men making candles, the gold-beater thumping monotonously with his mallet, the quick-handed girl by his side, cutting and placing in books the leaves of metal so thin that a breath would destroy them; the dapper little women making their chubby hands muddy in preparing the clay for the skilled potter at the wheel; the carpet weavers, the American machine watchmakers, the brush-back makers, the Welshwoman with her spinning wheel, and the fancifully costumed ‘prentices in Old London shops were all so many centres of attraction, surrounded throughout the day by changing, but ever admiring knots of spectators.Footnote 56

Thus, opportunities for interaction between visitors and staff were crucial in structuring visitors’ movement through the streets. Moreover, visitor pleasure is shown to arise from the opportunity to observe the juxtaposition of people from a variety of places and a variety of times, as the sketches by ‘Marksman’ again show; they combine the spectacle of the crowd with the spectacle presented at Old Manchester and Salford (see Figures 1, 6 and 9). Incongruity was positively enjoyable.

Both the interest in stocks and pillories, and visitors’ attraction to people making and doing things, speak to the centrality of bodily experiences and shared performances in these enactments of the past.Footnote 57 Another newspaper report suggests that ‘ladies’ were particularly keen to enter houses and buildings, ascend the ‘narrow staircases’, ‘dive into the darksome little upper rooms’ and look out of the windows onto the street scene below.Footnote 58 This is particularly interesting in suggesting a hybrid mode of engaging with these attractions; both enjoying the bodily experience of inhabiting different spaces, and gaining a vantage point which provided some of the panoptic properties of modern buildings.Footnote 59 Images and accounts show visitors as keen to ‘inhabit’ the buildings and experience the environment corporeally, climbing steps and entering buildings, and, at Manchester, enjoying the sensation of walking on cobblestones (Figure 12).Footnote 60 Manchester's Corporation had supplied a quantity of old cobblestones which were built into Old Manchester and Salford, and formed an important part of the reconstruction's claim to be bigger and better than any that had come before. Initially, they were so prominent as to be ‘inconvenient to the feet’, so an extra layer of cement was deposited so that they protruded less (the final effect can be seen quite well in Figure 11).Footnote 61 But their role providing a different bodily experience of walking was clearly important to visitors. For Landsberg, from the end of the nineteenth century bodies became an important site for empathy and for the creation of new sorts of collective memory; the ‘experiential’ became a mode of knowledge acquisition.Footnote 62 It emerged from the technical, social and cultural changes engendered by modernity, and increasingly felt in urban environments by the end of the nineteenth century. We can, then, understand this interest in bodily engagement with the past as produced by people's haptic experience of modernity.Footnote 63 If walking the modern city is a form of poetry for de Certeau, then sitting in the stocks, walking on old cobbles, climbing ‘historical’ flights of stairs and watching intensely physical craft demonstrations were also forms of poetic interpretation and, importantly, appropriation of the past.Footnote 64 Overall, in fact, the ‘meaning’ of the old streets emerged far more through staff and visitor interaction, and bodily performances and experiences, than either imposition from above, or resistance of those meanings from below – it was a co-production.Footnote 65

Figure 12: ‘The International Health Exhibition at South Kensington: “reproduction of London in the Olden Time”’, Illustrated London News, 10 May 1884. Newspaper Image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.BritishNewspaperArchive.co.uk).

Conclusion

The development of urban heritage was an important part of the development of modern urban environments in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As cityscapes were redeveloped, there was a substantial popular interest, not just in the preservation and conservation of historic buildings, but in more complex and commercial ways of keeping or inserting traces of the past in the urban environment. Although ‘top-down’ national and bourgeois historical narratives were visible in reconstructed historic streets as in preservationist legislation, a large number of actors showed interest in experiential, co-produced heritage ‘moments’, which rested on sophisticated performances by a range of staff and visitors; insisted on the importance of embodied engagement with historic (or faux historic) fabric; and which endowed the people of the past, through their modern proxies, with gendered, classed and ethnic bodies.Footnote 66 This developing sense of urban heritage suggests strongly that de Certeau's view of the relationship between walking the city and remembering it is applicable even in what may be seen as a staged and commodified representation; indeed, the commodified and commercialized nature of this memory was key to its success in the modern city. This commodified memory functioned similarly to the highly commodified prosthetic memory discussed by Alison Landsberg; like that, it relied on embodied, haptic performance of history to turn confected traces of the past into new memories enabled by new technology, which sutured people to periods and events to which they had no organic link.Footnote 67 Viewed in this way, it is clear that such popular manifestations of urban heritage were a much more important way of producing and exploring collective memory, and organizing the relationship between past and present in the modern city, than has been acknowledged. The commercial environment of international exhibitions around 1900 was, therefore, one of great importance in the creation of new memory practices, ones which would work for a modern city and a mass culture.