The suicide rate in Sweden decreased by 25% during the 1990s. After analysing trends for the years 1978–96, I proposed that the cause might be the concurrent increased use of antidepressants, and data from Norway, Denmark, Finland, Hungary and the USA supported this hypothesis (Reference IsacssonIsacsson, 2000). However, naturalistic studies do not allow definite conclusions, which is why the importance of testing this hypothesis in other studies was stressed. Reseland et al (Reference Reseland, Bray and Gunnell2006) recently published an ‘extended’ (1961–2001) analysis of suicide and the use of antidepressants in the four Nordic countries. They interpreted two non-significant findings as ‘contrasting’ with my data: in Sweden and Denmark, the decrease in suicide started before the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); the suicide rate in Norway later stabilised despite increased use of SSRIs.

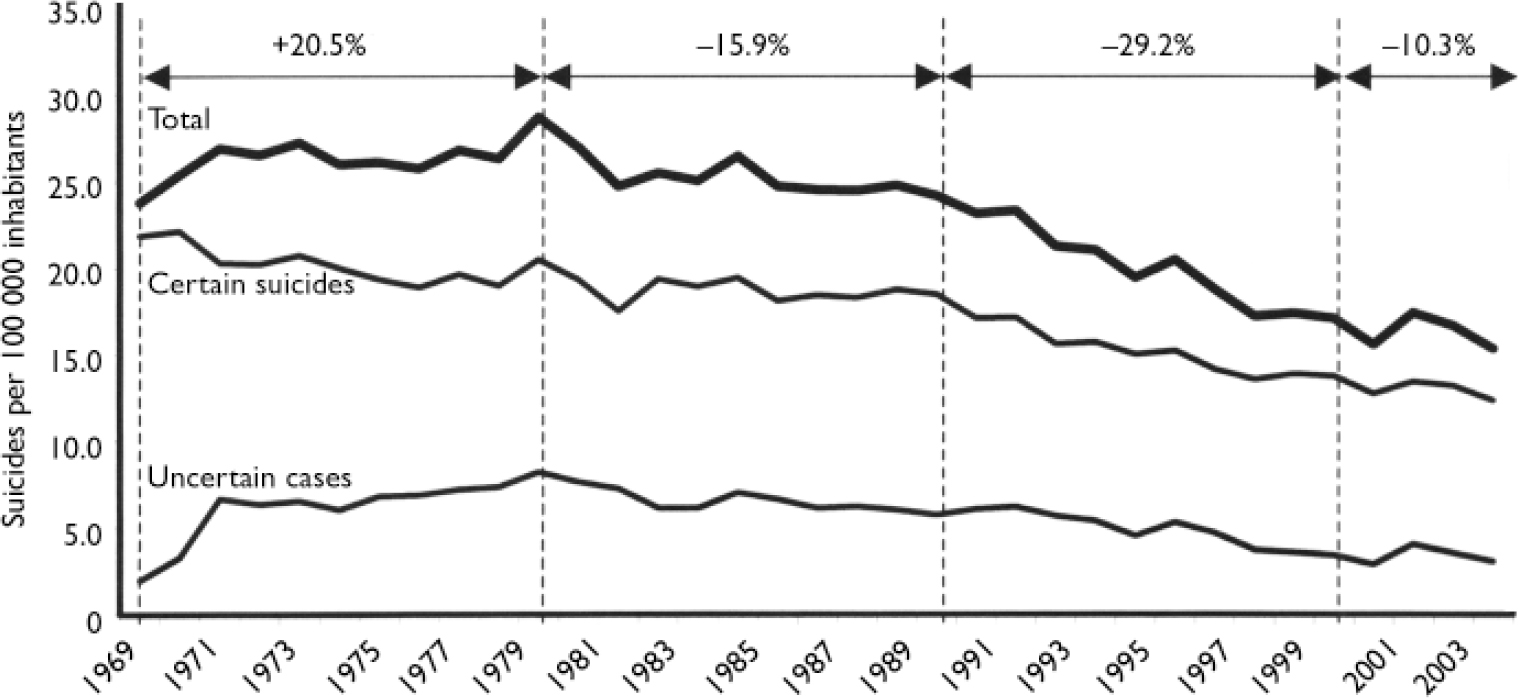

However, the classification of deaths was changed in 1969 with the introduction of the category of uncertain cause of death in ICD–8. Statistics before 1969 are therefore not comparable with later data. Furthermore, forensic pathologists only gradually became accustomed to the new classification and the proportions of suicides to uncertain cases appear to have stabilised first in 1979 (Fig. 1). Thus, the decrease found by Reseland et al in ‘certain suicides’ in 1969–79 may be an artefact. A better way of handling the uncertain cases might be to add them to the certain suicides (Reference Linsley, Schapira and KellyLinsley et al, 2001). This would mean that the Swedish suicide rates increased in 1969–79, decreased in 1979–89 and decreased rapidly in 1989–99. The ‘pre-SSRI’ decrease in 1979–89 may be a result of the increased use of tricyclic antidepressants.

Fig. 1 Suicide rates in Sweden 1969–2003. Percentages refer to the total (suicides + uncertain cases).

Stabilisation in suicide rates is to be expected. Antidepressants cannot save people who avoid doctors, who have treatment-refractory depression, schizophrenia or substance misuse from dying by suicide.

I conclude that the data of Reseland et al do not challenge the hypothesis that the increased use of antidepressants is the cause of the prominent decrease in suicide rate since 1990. Moreover, some ten studies provide strong evidence to support the hypothesis (Reference Isacsson and RichIsacsson & Rich, 2005; Reference Ludwig and MarcotteLudwig & Marcotte, 2005).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.