Evidence suggests that childhood trauma increases risk for the development of psychosis and is associated with symptom severity across the psychosis spectrum.Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross1–Reference Ered, Gibson, Maxwell, Cooper and Ellman3 Childhood trauma is also associated with earlier age at onset and higher number of hospital admissions in individuals with schizophrenia,Reference Rosenthal, Meyer, Mayo, Tully, Patel and Ashby4 as well as a higher degree of positive symptoms.Reference Uyan, Baltacioglu and Hocaoglu5,Reference Wang, Xue, Pu, Yang, Li and Yi6 Importantly, evidence suggests that childhood trauma pre-dates the onset of psychotic symptoms, suggesting a causal relationship.Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross1 In addition to positive symptoms, childhood trauma is also associated with negative symptoms, such as anhedonia.Reference Kirkpatrick, Fenton, Carpenter and Marder7 It is particularly important to understand the development of negative symptoms, as they often present prior to the onset of positive symptomsReference Mason, Startup, Halpin, Schall, Conrad and Carr8,Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly and Dell'Olio9 and are typically associated with worse real-world outcomes, such as deficits in social functioning (i.e. level of social contact and ability to maintain interpersonal relationships) and role functioning (i.e. level of functioning at school or work).Reference Devoe, Braun, Seredynski and Addington10 These findings indicate that childhood trauma may contribute to psychosis risk, as well as negative symptoms specifically, and thus represents a target for early intervention.

Anhedonia has traditionally been defined as an inability to experience pleasure and can be further divided into consummatory (i.e. in-the-moment hedonic capacity) and anticipatory (i.e. ability to anticipate future enjoyment) anhedonia. Among individuals with frank psychosis, those who have experienced childhood trauma or early adversity were more likely to report symptoms of anhedonia.Reference Sweeney, Air, Zannettino and Galletly11 A similar relationship between childhood trauma and anhedonia has been found in those experiencing other forms of psychopathology, such as depressive disorders,Reference Fan, Liu, Xia, Li, Gao and Zhu12,Reference Sonmez, Lewis, Athreya, Shekunov and Croarkin13 as well as in non-psychiatric controls.Reference Fan, Liu, Xia, Li, Gao and Zhu12 However, to our knowledge, the relationship between childhood trauma and anhedonia is yet to be examined in individuals at CHR, as prior research on this population has typically focused on the relationship between childhood trauma and positive symptoms. Further, it remains unclear whether childhood trauma is differentially associated with consummatory or anticipatory anhedonia.

One potential explanation for the link between childhood trauma and psychosis is an increase in stress sensitivity, which can occur when early exposure to stress or adversity, such as childhood trauma, increases sensitivity or reactivity to stressful events later in life, as well as increasing the likelihood that daily events will be perceived as stressful.Reference Collip, Myin-Germeys and Van Os14 This impaired stress tolerance may contribute to higher levels of negative emotions and psychotic experiences in reaction to daily life stress, which constitutes a vulnerability for developing frank psychosis.Reference Myin-Germeys and van Os15 Additionally, perceived uncontrollability of stressful events has been linked to both consummatory and anticipatory anhedonia among CHR youth.Reference Gerritsen, Bagby, Sanches, Kiang, Maheandiran and Prce16 Using structural equation modelling, Pelletier-Baldelli and colleaguesReference Pelletier-Baldelli, Strauss, Kuhney, Chun, Gupta and Ellman17 found that perceived stress directly influences both consummatory and anticipatory anhedonia in a sample enriched for psychosis (i.e. scoring above cut-offs on psychosis-risk screening questionnaires), which in turn predicts deficits in social functioning. Therefore, increases in perceived stress may be a contributing factor in the development of anhedonia.

The role of childhood trauma in the perceived stress–anhedonia relationship has not yet been explored, despite consistent evidence that childhood trauma is associated with sensitisation to later stress and anhedonia.Reference Collip, Myin-Germeys and Van Os14,Reference Raymond, Marin, Majeur and Lupien18,Reference Stanton, Holmes, Chang and Joormann19 Therefore, the current study aimed to determine whether perceived stress mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and both forms of anhedonia (anticipatory and consummatory) for CHR individuals. We hypothesised that childhood trauma would be associated with anhedonia via perceived stress. Further, although we know that anhedonia is characteristic of psychosis, it also is a hallmark feature of depression, a highly comorbid disorder in CHR individuals. Understanding distinct and overlapping risk trajectories will help to pinpoint potential treatment targets. Therefore, we examined whether the same mediating relationship is present for individuals with depressive disorders, as well as community controls, to assess specificity.

Method

Participants

Study participants were young adults from three large, racially, ethnically and socioeconomically diverse catchment areas in the USA: Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania; Cook County, Illinois; and Baltimore County, Maryland. Participants (n = 5944) were recruited from local communities and universities through flyers and online sources (e.g. social media, student courses, Craigslist) to complete a baseline assessment of self-report questionnaires online using Qualtrics (Provo, Utah). A subset of these participants (n = 807) was invited to complete in-person semi-structured interviews based on being above the pre-determined cut-off scores on two psychosis-risk questionnaires (≥8 positive symptom items on the Prodromal QuestionnaireReference Loewy, Bearden, Johnson, Raine and Cannon20 or ≥2 endorsements of ‘somewhat’ or ‘definitely agree’ on the PRIME screenReference Miller, Cicchetti, Markovich, McGlashan and Woods21) or randomly selected from a pool of participants below both cut-off scores.Reference Ellman, Schiffman and Mittal22 Starting in May 2020, interviews (n = 244) were conducted remotely via Zoom (owing to the COVID-19 pandemic) with cameras required to be on. There were no exclusion criteria for the study beyond being fluent in English and being within the age range of 16–30 years, which is based on known risk periods for psychosis.

Ethics statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Temple University (Approval No. 13359), Northwestern University (Approval No. STU00205348) and University of Maryland Baltimore Country (Approval No. YS17JS20227). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Childhood trauma was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form (CTQ).Reference Bernstein, Fink, Handelsman, Foote, Lovejoy and Wenzel23 This is a self-report inventory assessing five types of childhood maltreatment (emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect) occurring before the age of 16. The CTQ has shown validity in both clinical and community samples for ages 12 and up, as well as convergence with the Childhood Trauma Interview.Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge and Ahluvalia24,Reference Bernstein and Fink25 In the current study, two of the three sites removed items that could lead to reportable situations (i.e. physical and sexual abuse) owing to the online nature of the questionnaire and potential inability to contact participants. Therefore, the remaining 12 items were summed to create a modified total score (α = 0.87) which assesses emotional abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect. A subset of the sample (n = 255) was given the full CTQ Short Form, allowing us to determine a Pearson correlation of 0.89 between the full questionnaire and shortened version.

Perceived stress was measured by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS),Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein26 which is a 14-item self-report scale assessing the extent to which daily life events in the past month are viewed as stressful and uncontrollable. The PSS has shown good reliability and validity Reference Cohen27–Reference Hewitt, Flett and Mosher29 and has successfully discriminated between psychosis populations and controls.Reference Horan, Brown and Blanchard30–Reference Palmier-Claus, Dunn and Lewis32 The total PSS score (α = 0.89) was used.

Anhedonia was assessed with the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS).Reference Gard, Gard, Kring and John33 The TEPS is a measure of an individual's disposition to experience pleasure and has subscales for both anticipatory pleasure (e.g. pleasure associated with expectation of reward; TEPS-ANT) and consummatory pleasure (e.g. pleasure derived while engaged in an activity; TEPS-CON). The TEPS has exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach's alphas of 0.71−0.80),Reference Gard, Gard, Kring and John33–Reference Strauss, Wilbur, Warren, August and Gold35 high test–retest reliabilityReference Gard, Gard, Kring and John33,Reference Strauss, Wilbur, Warren, August and Gold35 and strong construct and discriminant validity.Reference Gard, Gard, Kring and John33,Reference Gard, Gard, Mehta, Kring and Patrick34,Reference Favrod, Ernst, Giuliani and Bonsack36 In the current study, the TEPS was used as a measure of anhedonia, lower scores indicating higher anhedonia. TEPS-ANT (α = 0.76) and TEPS-CON (α = 0.72) were our variables of interest.

CHR status was determined by the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Syndromes (SIPS).Reference McGlashan, Walsh and Woods37 The SIPS is a semi-structured interview which assesses psychosis-risk syndromes and has exhibited predictive validity of conversion to psychosis,Reference Cannon, Cadenhead, Cornblatt, Woods, Addington and Walker38 as well as specificity and interrater reliability.Reference Miller, McGlashan, Rosen, Somjee, Markovich and Stein39–Reference Woods, Addington, Cadenhead, Cannon, Cornblatt and Heinssen41 In the current study, all SIPS interviews were administered by individuals who had undergone extensive training led by a SIPS-certified trainer and met reliability standards (intraclass correlation coefficient ICC > 0.80 on positive symptom ratings). Additionally, any CHR status was verified during a weekly cross-site consensus meeting led by a SIPS-certified trainer. Participants were considered at CHR (n = 117) if they met criteria for at least one of three psychosis-risk syndromes: attenuated positive symptom syndrome (n = 116), brief intermittent psychotic syndrome (n = 0) and genetic risk and functional decline (n = 2). To address the issue of comorbidity, participants were excluded from the CHR group if they also met diagnostic criteria for a current depressive disorder (n = 24).

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, Research Version (SCID)Reference First, Williams, Karg and Spitzer42 has been termed the gold standard for determining clinical diagnoses. In the current study, all SCID diagnoses were confirmed in weekly meetings with a clinical supervisor. The Mood Disorders module was used to determine lifetime history of depression, including major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder and other specified depressive disorder. Presence versus absence of lifetime depressive disorder was the variable of interest to determine group status (n = 286). Individuals were considered community controls (n = 124) if they did not meet criteria for any current or past SCID diagnosis. Comorbid diagnoses for the clinical groups (CHR and depression) can be found in Table 1.

Table 1 Sample characteristics by group

CHR, clinical high risk for psychosis; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; TEPS, Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale; ANT, anticipatory pleasure; CON, consummatory pleasure.

1 Sex assigned at birth.

Data analysis

First, the dependent variables (TEPS-ANT and TEPS-CON) were examined for normality statistically by examining skewness and kurtosis values and by visually inspecting the data. Next, bivariate analyses using Pearson's correlations were conducted to determine whether there were significant relationships between the main independent variable (childhood trauma) and the potential mediator (perceived stress) and the dependent variables (TEPS-ANT and TEPS-CON), as well as whether the potential mediator (perceived stress) was associated with the dependent variables (TEPS-ANT, TEPS-CON).Reference Baron and Kenny43 Additionally, age and sex assigned at birth (termed sex hereafter) were tested as potential covariates by determining whether they were associated with the independent and dependent variables (childhood trauma and anhedonia respectively).

Statistical analyses were conducted in R44 for Windows using version 3.6.2 of RStudio.45 The lavaan packageReference Rosseel46 was used for analyses. Specifically, a multigroup mediation analysis for the community controls and the CHR and depression groups was run so that group differences in direct and indirect effects could be examined.Reference Ryu and Cheong47 An initial model was estimated that permitted regression coefficients of all three paths to differ between groups (i.e. freely estimated). Next, a series of models were estimated that introduced constraints on individual paths by holding the regression coefficients of the path equal across groups. Each constrained model was compared with the initial freely estimated model. If the models did not significantly differ in model fit, this indicated that there were no significant differences between groups and the constrained path is preferable to the freely estimated path. Mediation effects were tested using a bootstrap estimation approach with 5000 samples. Significant mediation was determined by the 95% confidence interval not including zero.Reference Preacher and Hayes48

Four sensitivity analyses were run to assess consistency of results after accounting for various changes to the model parameters. First, for models in which group was a significant moderator, a multigroup mediation model was run in which all CHR individuals with past diagnoses of depressive disorders (n = 65) were removed from the CHR group. Next, multigroup models were run with CHR individuals who also met criteria for a current depressive disorder (n = 24) included in the CHR group. These were not run for models that were pooled across groups. Third, models were run using only the subset of individuals who completed the full CTQ Short Form (i.e. including incidences of physical and sexual abuse; n = 152). Last, owing to the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stress and depressive symptomology, models were run with the subset of individuals assessed before the start of the pandemic (n = 359).

Results

Participants’ demographic and descriptive characteristics can be seen in Table 1. Compared with the depression group, the CHR group had a higher rate of social anxiety disorder (χ²(1) = 6.68, P < 0.01), but there were no other significant differences in comorbid diagnoses between the clinical groups.

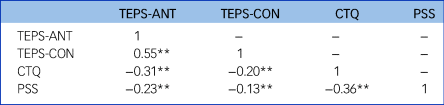

All study variables were significantly correlated with each other (Table 2). Age was correlated with TEPS-ANT (r = −0.08, P < 0.05) and CTQ (r = 0.11, P < 0.01) such that older age was associated with greater levels of anticipatory anhedonia and more instances of childhood trauma. Sex was correlated with TEPS-CON (r = 0.08, P < 0.05) and PSS (r = 0.09, P < 0.05). Therefore, to take a conservative approach, both age and sex were included as covariates in subsequent models.

Table 2 Correlations among study variables

TEPS, Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale; ANT, anticipatory pleasure; CON, consummatory pleasure; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale.

**P < 0.01.

First, we examined the indirect effect of childhood trauma on TEPS-ANT through perceived stress in a freely estimated model (i.e. all three paths were allowed to vary across groups) that demonstrated good model fit (χ2(21) = 138.06, P < 0.001; root mean square error of approximation RMSEA < 0.001, 90% CI 0.00–0.07; comparative fit index CFI = 1.00; standardised root mean squared residual SRMR < 0.001). We further examined the specific paths by introducing constraints on individual paths and testing for overall differences in model fit. Compared with the freely estimated model, a model with the CTQ–PSS path constrained and a model with the CTQ–TEPS-ANT path constrained did not show significantly worse fit (χ²(2) = 0.62, P = 0.73 and χ²(2) = 0.74, P = 0.69 respectively), suggesting no group differences in these paths. However, a model with the PSS–TEPS-ANT path constrained showed a significantly worse fit to the data (χ²(2) = 9.52, P = 0.01), suggesting differences in this relationship across groups. Therefore, in the final model, the CTQ–PSS and CTQ–TEPS-ANT paths were constrained and the PSS–TEPS-ANT path was allowed to vary across groups (χ2(21) = 138.06, P < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.00, 90% CI 0.00–0.07; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.01). In this model (Fig. 1), perceived stress mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and anticipatory anhedonia for the CHR and depression groups, but not for community controls. There was a significant difference in indirect effect between community controls and the CHR group (b = 0.10, s.e. = 0.03, z = 2.91, P < 0.01), but not between community controls and depression (b = 0.04, s.e. = 0.03, z = 1.72, P = 0.09). The difference in indirect effect between the CHR and depression groups was nearly significant (b = −0.06, s.e. = 0.03, t = −1.94, P = 0.05), indicating that the effect was stronger for CHR at the trend level. The direct paths from CTQ to PSS (b = 0.26, s.e. = 0.03, t = 7.44, P < 0.001) and from CTQ to TEPS-ANT (b = −0.16, s.e. = 0.04, t = −4.74, P < 0.001) were significant for all three groups. However, the direct path from PSS to TEPS-ANT was significant for the CHR (b = −0.42, s.e. = 0.10, t = −4.40, P < 0.001) and depression (b = −0.20, s.e. = 0.06, t = −3.50, P < 0.001) groups, but not for community controls (b = −0.03, s.e. = 0.08, t = −0.37, P = 0.71). Further, this relationship was significantly stronger for the CHR group compared with the depression group (b = −0.22, s.e. = 0.12, t = −2.01, P < 0.05).

Fig. 1 Multigroup structural equation model predicting anticipatory anhedonia for community controls and the clinical high risk for psychosis (CHR) and depression groups.

Significant indirect effect was determined by the 95% confidence interval not including zero. ***P < 0.001. TEPS, Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale.

For the consummatory subscale, there was no significant difference in model fit between the freely estimated model and one in which all three paths were constrained across groups, indicating that there is no variation in path coefficients by group. Therefore, a single mediation model was estimated for all participants (χ2(21) = 100.342, P < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.00, 90% CI 0.00–0.05; CFI = 1.0; SRMR = 0.01). In this model (Fig. 2), perceived stress mediated the relationship between CTQ and TEPS-CON. Further, CTQ was associated with both PSS (b = 0.26, s.e. = 0.03, t = 7.47, P < 0.001) and TEPS-CON (b = −0.07, s.e. = 0.03, t = −2.41, P = 0.02), and PSS was also associated with TEPS-CON (b = −0.13, s.e. = 0.04, t = −3.75, P < 0.001).

Fig. 2 Structural equation model, pooled across groups, predicting consummatory anhedonia.

Significant indirect effect was determined by the 95% confidence interval not including zero. *P<0.05; ***P < 0.001. TEPS, Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale.

Sensitivity analyses

First, a follow-up analysis of the multigroup TEPS-ANT model was run in which all individuals with past diagnoses of depression were removed from the CHR group. Although the CHR group size was significantly reduced (n = 52), the indirect effect of childhood trauma on TEPS-ANT through perceived stress was significant. Further, there was a significant difference in indirect effects between the CHR and depression groups (b = −0.11, s.e. = 0.04, t = −2.846, P < 0.01), indicating that the indirect effect was stronger for the CHR group. Second, the TEPS-ANT model was run with CHR individuals who also met criteria for a current depressive disorder (n = 24) included in the CHR group. In this model, there was a significant difference in indirect effect between community controls and the CHR group (b = 0.10, s.e. = 0.03, t = 3.08, P < 0.01) and between the CHR and depression groups (b = −0.06, s.e. = 0.03, t = −2.15, P = 0.03), with the effect being strongest for the CHR group. These follow-up analyses were not run for TEPS-CON, as group was not a significant moderator for TEPS-CON models and the mediation model was pooled across groups. Third, both the TEPS-ANT and TEPS-CON models were run using only the subset of individuals who completed the full CTQ Short Form (i.e. including incidences of physical and sexual abuse) and the indirect effect of childhood trauma on TEPS-CON through perceived stress was no longer significant, which may have been due to loss of power. Last, both models were run with the subset of individuals assessed before the start of the pandemic and all substantive conclusions remained the same. Full results of the sensitivity analyses can be seen in the supplementary material, available at https://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.185.

Discussion

We demonstrated that childhood trauma is associated with higher levels of consummatory and anticipatory anhedonia via the indirect effect of perceived stress for individuals at CHR and those with depression. These findings extend existing stress–anhedonia models by including childhood trauma in the model, suggesting a transdiagnostic pathway through which childhood trauma contributes to anhedonia across the psychosis spectrum, as well as in depressive disorders. Childhood trauma was independently associated with increases in perceived stress and anhedonia, regardless of group status. In contrast, group status moderated the relationship between perceived stress and anticipatory anhedonia, with this association being strongest for CHR individuals. Our findings provide evidence that increases in perceived stress may constitute an important target for early intervention, particularly for individuals at risk for developing psychosis who have a history of trauma.

Early adversity likely contributes to the development of psychosis in part through dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which is integral in the body's response to stress.Reference Myin-Germeys and van Os15,Reference Raymond, Marin, Majeur and Lupien18 Further, it has been suggested that altered HPA functioning, and resulting increases in stress sensitivity, may contribute to anhedonia through the release of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), which interferes with mesolimbic functioning, thereby reducing reward motivation.Reference Stanton, Holmes, Chang and Joormann19 The findings of the current study align with previous work utilising time-lagged multilevel modelling, which found that activity-related stress (i.e. one's appraisal of one's capability, control and enjoyment of the current activity) is associated with increases in anhedonia for both the CHR state and first-episode psychosis.Reference Gerritsen, Bagby, Sanches, Kiang, Maheandiran and Prce16 Similarly, perceived uncontrollability of stressful events has been linked to anhedonia, as well as blunted midbrain dopamine responses, for individuals with depression.Reference Pizzagalli49 The current study adds to this literature by providing evidence that increases in perceived stress may constitute a potential mechanism through which early trauma contributes to anhedonia. Further, although this mechanism appears to be transdiagnostic, our findings suggest that the relationship is strongest for CHR individuals with respect to anticipatory anhedonia.

Interestingly, there were no significant group differences in any of the paths involving consummatory anhedonia. One potential explanation would be that this is due to limitations of the TEPS, which is prospective and hypothetical in nature. Although most self-report measures require thinking retrospectively to report past incidences, the TEPS requires the participant to imagine a specific situation and predict a future emotional response, which uses semantic rather than experiential knowledge about emotions.Reference Strauss and Gold50 We utilised the TEPS in the current study because it is used extensively in the psychosis-risk literature and has been recommended by the US National Institute of Mental Health Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative. However, it has been noted that the TEPS may reflect cognitive processes involved in the appraisal of hedonic experience as opposed to actual consumption of rewards.Reference Strauss and Gold50 Alternatively, our findings may indicate that childhood trauma leads to consummatory anhedonia via increases in perceived stress regardless of psychopathology. It has been suggested that different neural mechanisms are involved in anticipatory and consummatory anhedonia. For example, consummatory pleasure involves initial responsiveness to reward and is mediated by opioid and GABAergic connections of the mesolimbic circuit, with projections starting in the nucleus accumbens, whereas anticipatory pleasure relies on reward prediction (i.e. the ability to attribute incentive value or salience to reward-predicting cues to guide decisions),Reference Waltz, Frank, Robinson and Gold51 which is partly moderated by dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA).Reference Barch, Pagliaccio and Luking52 It has been suggested that CRF interferes with mesolimbic functioning by influencing dopamine release in the VTA.Reference Stanton, Holmes, Chang and Joormann19 Although we did not examine these neural mechanisms directly in this study, this body of literature could potentially explain why HPA-axis dysfunction, and associated increases in perceived stress, are particularly relevant to anticipatory anhedonia. Previous findings have established that individuals with schizophrenia show intact responsiveness to reward (i.e. consummatory pleasure), but show deficits in anticipatory pleasure,Reference Strauss and Gold50 potentially due to difficulty integrating salient information during decision-making.Reference Heerey, Bell-Warren and Gold53 However, this distinction is less clear among CHR samples, as previous research has found that individuals at CHR exhibit deficits in both consummatory and anticipatory pleasure.Reference Schlosser, Fisher, Gard, Fulford, Loewy and Vinogradov54,Reference Strauss, Ruiz, Visser, Crespo and Dickinson55 It has been suggested that anhedonia may not be specific to CHR, but rather associated with depression and other comorbid psychopathology.Reference Akouri-Shan, Schiffman, Millman, Demro, Fitzgerald and Rakhshan Rouhakhtar56 It should also be noted that the community control group exhibited TEPS-CON scores similar to those of the depression group. This may be reflective of rising rates of depression among young adults,Reference Goodwin, Dierker, Wu, Galea, Hoven and Weinberger57 despite not meeting clinical criteria for a depressive disorder, and highlights an important finding that should be followed up in epidemiological samples. Further, more research is needed to disentangle the mechanisms underlying anhedonia subtypes across diagnoses. However, our findings provide evidence that the link between perceived stress and anticipatory anhedonia is stronger for CHR individuals than for those with depression alone.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study was the use of a large community sample from highly diverse populations. However, it should be noted that the study employed community resources, such as flyers and internet sources, rather than targeting treatment-seeking populations such as clinics or hospitals. Although recruiting from non-clinical populations has been shown to reduce true risk for psychosis in the sample,Reference Fusar-Poli, Schultze-Lutter, Cappucciati, Rutigliano, Bonoldi and Stahl58 our study used validated psychosis-risk questionnaires to select participants for clinical interviews.

Some important limitations should be noted. First, owing to high comorbidity between psychosis risk and depression, it is difficult to determine the specificity of underlying mechanisms. Although it significantly reduced group size, a sensitivity analysis was conducted after removing individuals with a lifetime history of depression from the CHR group. In this sensitivity test, there was a significant difference in indirect effects between groups, indicating that the indirect effect was stronger for the CHR group. Further, the same was found when individuals with current comorbid depression were included in the CHR group, which may be a more naturalistic reflection of the CHR state. A second limitation of the study is the removal of reportable items from the CTQ (i.e. physical and sexual abuse), leaving a modified total score to be calculated using items that primarily assess neglect. However, sensitivity analyses were conducted with the subset of individuals who were given the full CTQ Short Form, and the results remained the same. Additionally, among those who completed the full questionnaire, the correlation between the excluded and included items was very high (r = 0.89). Third, this study relied on retrospective reporting of childhood trauma. Although the CTQ is a well-validated measure of early trauma,Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge and Ahluvalia24,Reference Bernstein and Fink25 it has been reported that only 52% of individuals who reported traumatic events in prospective studies reported having experienced trauma when asked retrospectively.Reference Baldwin, Reuben, Newbury and Danese59 Therefore, the prevalence of childhood trauma may be underreported in the current study. Fourth, it is possible that our findings are not specific to anhedonia but may also apply to other negative symptoms not examined in the current study, such as motivational deficits. Finally, although the occurrence of childhood trauma precedes the other variables examined in the study, cross-sectional data do not allow for establishing temporal precedence, particularly for perceived stress and anhedonia. Longitudinal or time-lagged studies may be better able to provide support for a causal relationship between perceived stress and anhedonia. However, the temporal sequence of our study variables would be difficult to parse apart, even in a longitudinal study, given that both perceived stress and anhedonia are common responses to trauma and therefore could occur simultaneously. The current study suggests that they are important constructs related to experiences of childhood trauma across groups, not only in psychosis populations.

Clinical implications

Our findings provide evidence that childhood trauma may contribute to anhedonia via increases in perceived stress. Although this mechanism is likely transdiagnostic, it appears that the association between perceived stress and anticipatory anhedonia is strongest among CHR individuals. Therefore, the early identification and treatment of high perceived stress may be an important intervention target, particularly for individuals at risk for developing psychosis. Cognitive–behavioural interventions, such as cognitive reappraisal and coping skills training, may be particularly beneficial, as they have been shown to reduce perceived stress.Reference Yusufov, Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, Grey, Moyer and Lobel60

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.185.

Data availability

Data for this study will be available through the National Institute of Health (NIH) on the National Data Archive (NDA) upon completion of the study. Prior to this, any interested parties can contact the corresponding author to request data.

Author contributions

K.J.O'B.: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing original draft, review and editing. A.E. and S.A.K.: conceptualisation, methodology, review and editing. T.M.O.: methodology, statistical consultant, review and editing. J.S. and V.A.M.: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, review and editing, funding acquisition. L.M.E.: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, review and editing, funding acquisition, supervision.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (5R01MH112612-05 to J.S., 5R01MH112545-05 to V.A.M., 5R01MH112613-05 to L.M.E., F31MH119720 to A.E.).

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.