The term food security is defined by the Committee on World Food Security as existing ‘when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy lifestyle’(1). The concept is further extrapolated by the FAO widely used six dimensions of food security (see Fig. 1)(2). It is clear that food security encompasses a complex and individualised network of equitable food access, safety, quality and culture-based preferences and can be experienced at the national, household or individual level. It is by understanding this network of interrelated variables that define food security, that the complexity of its inverse, food insecurity (FI), can be appreciated. FI is recognised as a global public health issue. Estimates indicate that 690 million people, nearly 9 % of the global population, are food insecure(3). Current trends project that this figure will surpass 840 million by 2030(3). In high-income countries, FI is associated with many factors, including being a single parent, having children under 18 years old, having low educational attainment, renting a house, having low socioeconomic status, receiving social assistance payments or being a member of a racial or ethnic minority(Reference Pollard, Landrigan and Ellies4,Reference Franklin, Jones and Love5) . As members of a racial or ethnic minority, refugees are vulnerable to FI. A refugee is defined as a person who has a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country and, as such, is unwilling or unable to safely return to it(6). Unlike many migrant groups, refugees often also have low socio-economic status and live in rental or government-supported accommodation, further increasing their association with FI risk factors(Reference Brell, Dustmann and Preston7,Reference Khoo, McDonald and Temple8) .

Fig. 1 The FAO Dimensions of Food Security*. *Adapted from Ashby S, Kleve S, McKechnie R, Palermo C. Measurement of the dimensions of food insecurity in developed countries: a systematic literature review. Public Health Nutrition. 2016;19(16):2887-96; HLPE. HLPE Report 15: Food security and nutrition: building a global narrative towards 2030. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 February 3]; Rome: HLPE; Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/ca9731en/ca9731en.pdf

For many refugees, their experience with FI begins before their resettlement in their final host country (which provides residency/citizenship). Around 85 % of refugees move from their country of birth (COB) to a low- to middle-income transition country where they await resettlement(9). The median stay in transition countries is 5 years(Reference Devictor and Do10). Often, accommodation is deficient and food is rationed or scarce(Reference Khakpour, Iqbal and Ghulam Hussain11–Reference Nunnery and Dharod13). The transition country experience has been reported to cause issues such as exclusion, discrimination and FI and affect physical and mental health(Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Pereira, Larder and Somerset15) . Mental conditions including loneliness, grief, gloom and psychological and distress physical conditions, such as malnutrition and anaemia, among children and women can be developed or exacerbated as result of the time in transition(Reference Pereira, Larder and Somerset15–Reference Kay, Leidman and Lopez18). From transition, some refugees are offered an opportunity to move to a resettlement country.

The top ten resettlement countries in 2018(9), in terms of refugee intake, were all high-income countries(19). These countries took 92 % of the 81 337 resettled refugees in 2018(9). Resettlement puts enormous pressure on policymakers and service providers in high-income countries to accommodate their growing refugee populations and provide necessities such as housing, education and food(20). Understanding the resettlement challenges of refugee populations in high-income countries is an important step in building evidence-based resettlement capacity. As refugees are known to be vulnerable to FI, one critical resettlement challenge is understanding how refugee food security can be procured and protected.

Food security involves a sufficient, safe and nutritious diet(1). A nutritious diet is known to support physical and mental health(21). Considering the nutritional issues faced by refugees in transition countries and their health on arrival in high-income countries(Reference Khakpour, Iqbal and Ghulam Hussain11–Reference Nunnery and Dharod13), the benefits of a nutritious diet become even more critical for this population. Associations have been reported between refugee FI in high-income countries and reduced intake of fruit, vegetables, red meat and milk products, and consequently low intakes of Fe, K, Ca, vitamins B1, B12 and other micronutrients(Reference Kendall, Olson and Frongillo22–Reference Wang, Min and Harris25). This has been shown to detrimentally affect the quality and diversity of the migrant, including the refugee, diet(Reference Kendall, Olson and Frongillo22–Reference Wang, Min and Harris25). Consequences of these dietary deficiencies can include malnutrition, undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies(Reference Kendall, Olson and Frongillo22,Reference Anderson, Hadzibegovic and Moseley24,Reference Wang, Min and Harris25) .

A 2020 systematic review reported the prevalence of household FI among refugees settling in high-income countries to be between 40 % and 71 %, depending on the measurement tool used and participant ethnicity(Reference Mansour, Liamputtong and Arora26). This is significantly higher than within the host country populations(Reference Mansour, Liamputtong and Arora26). Some studies set in high-income countries indicate the prevalence of refugee FI is highest in the first 2 years of resettlement(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13,Reference Girard and Sercia27–Reference Hadley and Sellen29) . Prevalence then slowly reduces, and approximately 10 years after arrival, the risk of FI is equivalent to that of the host population(Reference Girard and Sercia27). However, for some refugee sub-populations, the persistence of chronic barriers in the resettlement environment, including lack of host language proficiency, unemployment and poverty, has been associated with chronic vulnerability to FI(Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Anderson, Hadzibegovic and Moseley24,Reference Hadley, Zodhiates and Sellen28,Reference Khakpour, Sadeghi and Jenzer30–Reference Vahabi, Damba and Rocha32) .

Review rationale and objective

Refugees are highly vulnerable to FI. Understanding the population’s food security needs is a vital part of successful resettlement. Over 90 % of the world’s refugees are resettled in high-income countries(9), yet there is a paucity of data providing insight into refugee FI in this environment. The objective of this review was to scope the current literature to identify themes, locate evidence gaps and develop a pathway for future investigation of FI amongst recently arrived refugees settling in high-income countries.

Prior to commencement of this review, a preliminary search for existing reviews on refugee FI was conducted on MEDLINE and Scopus. A 2017(Reference Lawlis, Islam and Upton33) and a 2020(Reference Mansour, Liamputtong and Arora26) systematic reviews were located. Unlike the located reviews, the current review’s focus is on multiple high-income countries and recently arrived refugees and is therefore substantially different from the existing reviews.

Method

The framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley, with enhancements by Levac et al, was used for the development of this review (see Table 1)(Reference Arksey and O’Malley34,Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien35) . The process outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews checklist was also followed(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin36). Review objectives, inclusion criteria, methods and draft charting table were developed as parts of the protocol(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin36). Eligibility criteria: The eligibility criteria stated that 50 % or more of study participants must be legally documented refugees who had recently arrived in their resettlement country. In this review, the term ‘refugees’ did not include asylum seekers or ‘immigrants’, due to differences in the groups’ rights, entitlements and resettlement trajectories. Based on the literature, ‘recently arrived’ was defined as having been in the resettlement country for 2 years or less(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13,Reference Girard and Sercia27–Reference Hadley and Sellen29) . Participants could have been from any COB. The review’s core concept was FI; therefore, studies focussed on household FI, food security, scarcity of food, food stress or dietary transition issues were included. Only original, peer-reviewed, published studies set in high-income countries, using the World Bank definition(19), were included.

Table 1 Framework for scoping review*

* Adapted from: Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13, 141–146.

Search strategy: The search was conducted between May and July 2020. A search update was conducted in February 2021. Search terms included papers disseminated between 2000 and 2020 but excluded those not published in English. A three-step search strategy was employed(Reference Peters, Godfrey and Khalil37). An initial search was conducted on MEDLINE and Scopus. Retrieved paper titles and abstracts were analysed for keywords and index terms. These were then used to develop the search plan. The second search used that plan to search MEDLINE, CINAHL, Scopus, Informit and EmBase. ProQuest and PsychArticles were added to the database list in February 2021, as they were then searched. Suitable databases were selected in consultation with a research librarian. All are well recognised in the aggregation of peer-reviewed health, nutrition and sociological literature. The search plan was iteratively updated as additional keywords and search terms were discovered. In the third search stage, the reference list of retrieved articles was searched.

Study selection: Duplicate papers were removed. Retrieved papers and abstracts were then screened against the eligibility criteria by the primary author. If further information was required, the authors of queried studies were contacted directly. Action regarding queried studies was discussed and agreed within the research team of four researchers. Study selection details are outlined in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Study Selection Flow Chart Using the PRISMA Diagram for Scoping Review Process

Data charting and synthesis: The selected studies were charted using the protocol data charting table(Reference Tricco, Lillie and Zarin36,Reference Peters, Godfrey and Khalil37) . Extracted data included author, year, participant characteristics, study design and method and reported issues regarding refugee FI. Using charting, frequency of issues was noted across studies. Issues were then grouped under themes and critically appraised by the team.

Results

A total of 332 papers were located. After screening, sixty seven were determined to be duplicates, leaving 265 papers. Of these, 237 did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining twenty-eight studies were reviewed. Authors were contacted if clarification was required. Subsequent to the procedure, a further eight were excluded. Four studies were excluded as the refugee resettlement timeframe was unknown or greater than 5 years, one had a sample of less than 50 % refugees, one was a review, one was not a primary study and one did not focus on the review’s core concepts. In all, twenty studies satisfied the eligibility criteria (see Fig. 2).

Study characteristics

Six different high-income countries were represented (Table 2). Seven of the twenty studies used a multi-country COB sample. Sub-Saharan Africans refugees were the focus of six studies, while Afghani refugees were the focus of three.

Table 2 Characteristics of included studies (n 20)

Nineteen studies were cross-sectional. Most used semi-structured group or individual interviews. Specific measures of FI included the Canadian Community Health Survey FI module(Reference Khakpour, Sadeghi and Jenzer30,Reference Vahabi, Damba and Rocha32,Reference Lane, Nisbet and Vatanparast45) , an FFQ(Reference Dharod, Croom and Sady31), a dietary recall(Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40) and modified versions of the United States Department of Agriculture’s Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) or food security scale(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13,Reference Girard and Sercia27,Reference Hadley and Sellen29,Reference Khakpour, Sadeghi and Jenzer30,Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo38,Reference Gichunge, Harris and Tubei43) and the Radimer-Cornell instrument(Reference Anderson, Hadzibegovic and Moseley24,Reference Hadley and Sellen29,Reference Dharod, Croom and Sady31) . In total, twelve studies used an adaptation of an existing FI tool. A charted summary of the studies can be seen in Table 3 (studies are identified by the first one or two letters of the country name).

Table 3 Charting of literature examining food insecurity issues among recently arrived refugees settling in high-income countries*

HH, households; FI, food insecurity; ME, Middle East; USDA, United States Department of Agriculture; COB, countries of birth.

* Studies are grouped by country and ranked in ascending order in terms of publication year. The coding represented the first letter (or initials for the UK), followed by the number in which they appear in the table. This code is then used to refer to the studies throughout the discussion.

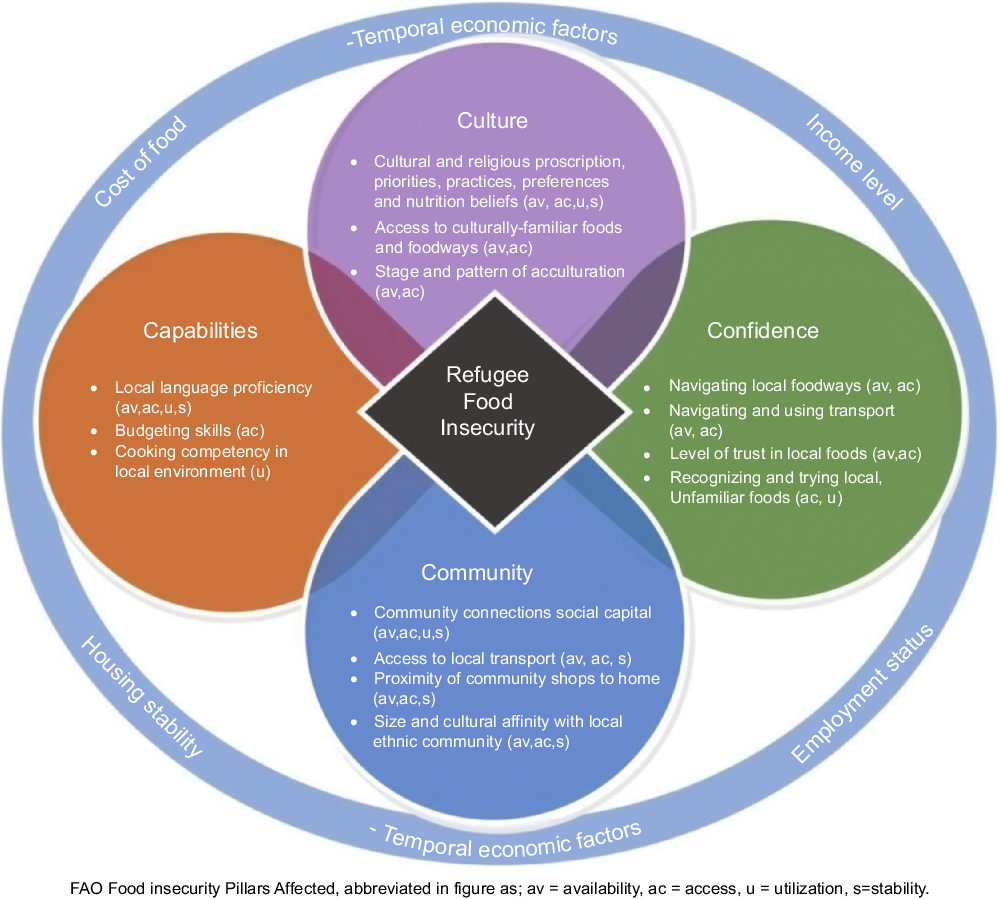

The literature indicated that factors such as income and access to transport affect food security among the general population, including refugees(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13,Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Coveney and O’Dwyer48,Reference Radermacher, Feldman and Bird49) . However, it also indicated that there are food security issues particularly related to refugees. These interconnected themes, such as culture, work in, around and across all of the FAO food security dimensions. The factors and themes work interdependently to influence and affect the dimensions. The FAO dimensions were therefore not the most appropriate way to capture the interconnected nature of the emergent themes, as reflected in Fig. 3, nor frame the presentation of results.

Fig. 3 Issues Affecting Refugee Food Insecurity: Emergent Themes

In Fig. 3, the four themes are encircled by temporal economic conditions including housing stability, income level, the cost of food and employment status as these are pivotal dimensions of FI with change in any of them influencing some, or all, of the factors comprising each of the themes. Housing and income are widely recognised as the bedrock of food security resilience as they impact a household’s individual and collective resilience resources(Reference Vahabi, Damba and Rocha32,Reference Webb, Coates and Frongillo50,Reference Renzaho and Mellor51) . For refugees, these factors are particularly important. A 2013 study of refugee resettlement in Australia found that, on average, refugees relocated three times in the first year(Reference Fozdar and Hartley52). Housing instability can reduce familiarity with the local food environment, navigation of transport and development of community connections(Reference Martin, Rogers and Cook53).

Theme 1: Cultural food connections and practices in the new environment

The literature suggests three interrelated ways that culture influences refugee FI. They are the culturally based food priorities and practices of the particular sub-population, the level of access to culturally familiar foodways and foods and the level and pattern of dietary acculturation(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13,Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Hadley, Zodhiates and Sellen28,Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo38–Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Gichunge, Harris and Tubei43,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) .

Culturally based food priorities, practices, preferences and nutrition beliefs were reported to influence food choices, budgets and household FI(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13,Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Hadley and Sellen29,Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Gallegos, Ellies and Wright42,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44,Reference Henjum, Morseth and Arnold54) . Study U4 reported that, culturally, a Somali complete meal contains meat(Reference Dharod, Croom and Sady31). It was therefore a food budget priority for many to purchase meat. The study found that a household’s intake levels of meat were reflected in the level of FI, and participants who reported eating meat daily were more likely to be FI(Reference Dharod, Croom and Sady31). While prioritising meat is not unique to Somali culture, this finding indicated that cultural preferences related to food priorities can affect FI. It also suggested that these preferences may impact diet quality, as it was presence of meat, not necessarily the meat quality, that was the cultural priority. Similarly, U5 reported higher consumption of freshly killed meat in FI Sudanese households, indicating a link between FI and food priorities in some cultures(Reference Anderson, Hadzibegovic and Moseley24).

Previous culturally influenced patterns and traditions related to food preparation and consumption may also be influenced by new food environments, impairing the food preparer’s ability to prepare nutritious and safe food(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44). Studies A1, A5, C4, C5 and N1 all reported that religious beliefs and food-related proscriptions can impact refugee FI by reducing availability and access(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Lane, Nisbet and Vatanparast45,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) . The challenge of accessing halal food was captured in a quote from a Syrian refugee in study C5, ‘…I have to read the ingredients and this is a challenge. I don’t buy anything that I don’t know or if it has gelatine or preservatives’(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12). Study C3 reported that Muslim participants paid a premium for halal foods, detrimentally impacting food budgets(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44). Cultural and religious differences in how and when FI was disclosed may also have hindered the ability to buffer negative shocks when FI was experienced(Reference Gallegos, Ellies and Wright42). It was suggested that culture may play a significant role in the lived experiences and reporting of FI. Even when FI was disclosed and help sought, cultural or religious issues could be an issue when seeking to address FI. Studies A5, C3 and C5 indicated that halal food was often not available from food banks, rendering the banks unsuitable for Muslim refugees(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44) .

The level of access to culturally familiar foods and foodways may also impact FI by altering access to traditional staples and disrupting traditional dietary patterns(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44). In new food environments, individuals lack norms for guidance regarding food choices, COB beliefs regarding nutrition may not accurately translate to the new setting and knowledge of local foods, particularly fruits and vegetables, may be limited(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47). Studies N1 and C1 found that locally available foods were unfamiliar, packaged or stored differently to COB, or did not taste the same as foods from refugees’ COBs(Reference Vahabi, Damba and Rocha32,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) . Studies A1, A2, C3, C5 and U1 reported that for some recognised foods, the taste and quality were deemed inferior to COB fresh foods(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Hadley and Sellen29,Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Renzaho and Burns41,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44) . Study A2 found that 96 % of its African participants (n 139) had difficulty locating traditional foods, such as camel milk and maize grain, during resettlement(Reference Renzaho and Burns41). As a result, they had to adapt recipes, using available ingredients to replace the traditional. Access to familiar foods and foodways was found to be particularly relevant during early resettlement, the most critical FI timeframe, when culturally and religiously appropriate foods can be the most difficult to access(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44).

Dietary acculturation may improve access to food, but adverse acculturation patterns may negatively affect nutrition(Reference Hadley and Sellen29,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret39,Reference Lane, Nisbet and Vatanparast45,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47,Reference Wahlqvist55) . Studies A1, A2 and N1 suggest that negative ‘forced’ acculturation patterns, due to reduced food access, may increase intake of nutritionally inferior foods(Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Renzaho and Burns41,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) . The literature indicates that acculturation factors in high-income countries, including lifestyle changes, working arrangements, lunchboxes and dinner as the main daily meal alters dietary acculturation patterns and, depending on the pattern, affects FI(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47).

Theme 2: Confidence in navigating new environments and foods

Confidence in navigating transport systems and local foodways and the safety of local foods may increase food access, availability and utilisation. Studies A3, C3, N1, U6 and U7 revealed that private or public transport access can improve food shopping options and the availability of affordable, desired foods for refugees(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret39,Reference Gallegos, Ellies and Wright42,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) . The connection between transport and food access is depicted by a quote from a Burundian participant in Study U7, ‘We didn’t know how to take the bus anywhere, so we had to walk to the grocery store to get some food’(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret39).

The level of confidence or trust in the safety of local foods also affects perceived food availability. Study C3 found concerns about the health and safety of local foods(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44). Studies A5, C5 and N1 also found that trust was a concern, even when recognisable foods were available(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) . Participants perceived local food, even fresh food, to be full of harmful chemicals. The trust issue extended to religious proscriptions(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47). A5 and N1 found that participants did not trust halal labelling in mainstream shops, opting to pay premium prices at ethnic shops, more trusted sources(Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) . A Study A5 participant said, ‘I still cannot trust foods here that they are halal. I have heard that if they have a code it means that it is not halal’(Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14). Similarly, one Study N1 Somali refugee said, ‘when you arrive here, and you know that a lot of things are not halal, then you become suspicious’(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47).

Theme 3: Community connections, social capital and ethnicity

The ethnicity of the local community, community connections and social capital may improve access to culturally appropriate foods and buffer negative food security shocks. Established ethnic precincts are characterised by large numbers of immigrants of the same ethnicity, which results in the establishment of more culturally familiar foods and foodways(Reference Collins, Reid and Groutis56). The literature suggests that living within established ethnic precincts may improve food availability. Studies U3 and N1 suggest that it is harder for the first ethnic wave of migrants during resettlement, as familiar foodways are not established and access to traditional foods is limited(Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo38,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) . For subsequent waves, help from previous arrivals facilitates resettlement.38 Study U3 found that Bhutanian refugees reported spending upwards of $600 per month on food and never having food shortages(Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo38). However, Burundi refugees on the same income reported going up to four days with no food. There was an established community of more than 300 Bhutanians in the city, but no Burundis. The authors argued that ready availability of culturally appropriate Bhutanian food reduced pressure on budgeting(Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo38).

Studies A1, A4, C3, C5, U7 and S1 found that community connections and developing social capital, a measure of trust, reciprocity and social network(Reference Putnam57), may assist by offering food security safety nets(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Khakpour, Sadeghi and Jenzer30,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret39,Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Gichunge, Harris and Tubei43,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44) . In their COB or transition country, many refugee sub-populations established habits and traditions which mitigated FI, including daily shopping, food gardens, familiar foodways, social capital and sharing food with extended family(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44) .

One Study A5 Afghani participant said, ‘In Pakistan if we ran out of a food, we will ask our neighbours […] here in Australia that is not possible.’(Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14) During early resettlement, traditional FI coping mechanisms may be absent or compromised, but living within ethnically aligned communities and developing connections and social capital can quickly build these coping mechanisms(Reference Anderson, Hadzibegovic and Moseley24,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44) .

Theme 4: Capabilities in the host language, food preparation and money handling

Most studies reported that individual capabilities, such as local language proficiency, cooking competency within the local environment and budgeting skills, may impact FI. Studies A4, C3, C5, U1, U2, U7 and S1 found that poor language skills are associated with the occurrence and severity of refugee FI, by impairing the ability to find familiar foods, navigate local foodways and restricting access to transport(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Hadley, Zodhiates and Sellen28–Reference Khakpour, Sadeghi and Jenzer30,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret39,Reference Gichunge, Harris and Tubei43,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44) . Transport improves access to affordable or culturally desirable foods, yet without language proficiency navigating barriers such as bus timetables and driving licenses is challenging(Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47,Reference Dubowitz, Acevedo-Garcia and Salkeld58–Reference Strijk, van Meijel and Gamel61) . Local language proficiency may improve foodway navigation as refugees can ask for assistance, read signs and labels and ask for help(Reference Hadley, Zodhiates and Sellen28,Reference Dharod, Croom and Sady31) . Studies A5 and N1 reported that language can also increase understanding of local food cultures and cooking practices by improving familiarity with local food use, new recipes, cooking methods, food safety and understanding cooking appliance instructions(Reference Kavian, Mehta and Willis14,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) .

Studies A1, C3, N1, UK1, S1, U3 and U7 reported that cooking capabilities within local environments, changes in cooking responsibilities, reductions in time available for food preparation and cooking and storage facilities can all impair food utilisation(Reference Khakpour, Sadeghi and Jenzer30,Reference Hadley, Patil and Nahayo38–Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44,Reference Sellen, Tedstone and Frize46,Reference Terragni, Garnweidner and Pettersen47) .

Further, study S1 indicated that lack of knowledge in food utilisation was a primary FI challenge(Reference Khakpour, Sadeghi and Jenzer30). U7 study’s discussion highlighted this issue with a quote from a Burundian refugee, ‘In Africa, I used to cook on charcoal or sometimes firewood, but in the US the stove was new to me… when we forgot how to use it we would stop eating’(Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret39).

The differences in the foodways and currencies of high-income countries and countries of birth require new budgeting and money-handling capabilities. Foodways include food acquisition, gardening practices, food preparation and mealtimes(Reference Spivey and Lewis62). Studies A3, C4, C5, U2, U5 and S1 found that a lack of such skills can impair food access(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Anderson, Hadzibegovic and Moseley24,Reference Hadley, Zodhiates and Sellen28,Reference Gallegos, Ellies and Wright42,Reference Lane, Nisbet and Vatanparast45) . In the shopping environments of high-income countries, budgeting skills may need to accommodate changes in shopping frequency and location, saving and bulk and discount buying(Reference Hadley, Zodhiates and Sellen28,Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40) . A1 found that poor budgeting skills and increased access to foods such as sugar, sugar-sweetened beverages and oils lead to an increase in the purchase and intake of such(Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40). The intake of relatively more expensive foods, such as COB fruits and vegetables, was reduced. A3 reported that budgeting issues were a common reason for refugees running out of food(Reference Gallegos, Ellies and Wright42). Similarly, U6 found that FI participants spent more on food than their food secure counterparts, indicating that budgeting was a key skill in managing FI(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13).

Discussion

This review’s themes capture an interconnected network of factors that affect the food security status of refugees settling in high-income countries. However, underlying and influencing all of the factors are foundational food security issues that require discussion. The first of these is the socio-economic circumstances of refugees settling in high-income countries. A key determinant of FI is low income(Reference Rose63). In the USA, immigrants, including refugees, are twice as likely to live in households within the poorest income decile, falling below the national poverty threshold(64). Providing pathways to higher socio-economic brackets is particularly critical for food security status, as studies have shown that food budgets, including those of refugees, are considered to be a flexible household expense which can be adjusted to accommodate fixed costs, such as utilities(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Hadley, Zodhiates and Sellen28,Reference Gallegos, Ellies and Wright42) . Without addressing the social determinants of health which would prevent refugees independently growing their income, including language barriers and employment opportunities, chronic FI will ensue. While many resettlement countries do seek to address the social determinants affecting refugees, the direct link between the inequities and chronic FI required discussion, as addressing the themes highlighted in the review without addressing these determinants compromises outcomes.

The second foundational issue is ensuring that refugee FI is regularly and effectively measured and monitored in high-income countries. Canada and USA regularly use the HFSSM to measure population FI(Reference Loopstra65), but it is not tailored to refugees, so measurements among this population may not be accurate(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13). Effectively measuring and monitoring refugee FI would allow the scale and scope of the issue, and the effectiveness of initiatives, to be evaluated. The measurement tool adapted for and used in eight of the twenty studies reviewed was the HFSSM. This provided comparable measures across the studies. Adopting this approach may prove an excellent practice for those researching refugee FI in high-income countries as it may assist equitable cross-country comparison with refugee sub-populations.

The HFSSM is widely used to measure FI in high-income countries, but it has been validated among very few immigrant groups. The confluence of culture, language and food behaviours, evident in this review’s themes, means that tools like the HFSSM must be validated for language, as well as conceptual equivalency, if they are to accurately measure refugee FI.

Only then can the tools be used as sensitive and specific measures of a culturally complex issue like FI(Reference Lyles, Nord and Choi66,Reference Kwan, Napoles and Chou67) . Ensuring conceptual equivalency may allow culturally specific conceptualisation of food security to be understood and measured within the existing tools’ adapted framework. A 2015 study developed and validated a conceptually equivalent Chinese version of the HFSSM(Reference Lyles, Nord and Choi66,Reference Kwan, Napoles and Chou67) . Concepts such as ‘balanced meals’ were translated to convey a similar meaning within the Chinese cultural framework. Similarly, a Farsi version(Reference Rafiei, Nord and Sadeghizadeh68) and a Spanish version for children have been developed(Reference Rabbitt and Coleman-Jensen69). It would be beneficial for high-income countries to use this same process to develop conceptually equivalent versions for their refugee populations, particularly the fastest growing populations requiring resettlement, Syrian and South Sudanese(9). The tailored tools could be shared with other high-income resettlement countries and used to monitor FI over time. The culturally adapted tools may also be used for rapid assessment during early caseworker or healthcare interactions to determine FI status on arrival and during early resettlement, particularly among emerging populations, who may not enjoy the food security benefits of living in an ethnic enclave(Reference Gichunge, Harris and Tubei43).

Culture was identified as a central theme. This is unsurprising as food traditions are deeply ingrained behaviours important in maintaining family and community networks and acting as cultural anchors for displaced persons(Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44,Reference Janowski70–Reference Manz and Panayi74) . Capturing this, anthropologist Elaine Power coined the term ‘cultural FI’, defined as a lack of availability and access to culturally appropriate food items(Reference Power75). The cultural aspects of FI impact all migrant groups, not only refugees. However, differing pre-settlement experiences, social determinants of health and degrees of agency exist between refugees and other migrant groups(Reference Nunnery and Dharod13). These fundamental differences may be why there appears to be a stronger connection between refugees, culture and FI, than exists with other migrants. Recognising this inequity, refugee research, policies or programmes which can effectively encompass the cultural aspects of FI and also promote the agency of refugees may result in more equitable, sustainable solutions(Reference Hugman, Bartolomei and Pittaway76,Reference Hugman, Pittaway and Bartolomei77) . Refugee food gardens are one option which show promise(Reference Gichunge, Harris and Tubei43,Reference Strunk and Richardson78–Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph80) . A review of urban gardens in America’s Midwest found that refugee gardeners exercised agency in farming practices, garden management and planting choices. Karen, Chin and Kachin refugees grew a dietary staple, roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa), as it was unavailable in the local food system(Reference Strunk and Richardson78). To acquire the seeds, some drove to refugee communities in distant cities. Whilst promising, the research regarding refugee food gardens is disparate. Further exploration is required, specifically to understand how initiatives, such as refugee food gardens, can be designed to address all of the FAO food security dimensions and, importantly, how they can be scaled in high-income countries to become viable, sustainable solutions.

The reviewed studies identified social capital as a grass-roots mechanism used to mitigate FI(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Khakpour, Sadeghi and Jenzer30,Reference McElrone, Colby and Moret39,Reference Vincenzo, Crotty and Burns40,Reference Gichunge, Harris and Tubei43,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44) . Arising from this is the question of what role bridging v. bonding social capital plays for refugees in high-income countries, where bonding social capital is that which is developed within the ethnic community and bridging is between the host and ethnic communities(Reference Putnam57). Further, is it cultural dimensions or the size of the ethnic community which determines the type of social capital that is most effective for sustaining food security? Could digital platforms be used to expedite the development of social capital? Syrian refugees settling in Saskatoon Canada reported using Facebook and WhatsApp to facilitate access to culturally appropriate and affordable foods(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12). How did the refugees locate this resource? Could this idea be transferred to other cultures? Further research is required. Increased understanding of how bridging and bonding social capital and refugee FI intersect in high-income countries could inform programme and policy design that enables the development of social capital to buffer food security shocks.

In seeking to untangle the complexity of refugee FI, this review isolated themes for discussion. In reality, the themes are part of an interdependent network of variables that are vulnerable to multiple temporal factors. It is important to research the isolated variables, such as social capital, but for recognising their interdependence, it is vital to design and evaluate initiatives, utilising the identified themes, so that their effectiveness can be evaluated in situ. Considering high-income countries already have existing food security strategies and initiatives in place, how could the factors underpinning culture, confidence, capabilities and community be used to improve these existing strategies, so that they are effective for refugees? The literature suggests that existing strategies in high-income countries, such as food banks, in their current form are not effective for refugees due to the food not being culturally or religiously appropriate, transport barriers, work scheduling affecting access or refugees feeling uncomfortable using the services(Reference Vatanparast, Koc and Farag12,Reference Vahabi, Damba and Rocha32,Reference Moffat, Mohammed and Newbold44) . The Food Bank of Delaware used research data to improve availability and access by piloting a social entrepreneurship venture connected to their food bank(Reference Popielarski and Cotugna81). The model was based on Amish salvage markets and is similar to the community supermarket model(Reference Wills82). Groceries were purchased from a salvage good distributor and then sold at or slightly above cost. The store was staffed by volunteers or current food bank staff. Any profit made went back into the food bank to purchase new stock or was used to facilitate their overall mission to eliminate hunger. For food banks located near refugee ethnic enclaves, could this community supermarket model be adapted to pay heed to – the local community’s cultural needs, whilst being considerate of the confidence and capability levels of the local refugee community? Participatory design or co creation could be employed to exercise the agency of the refugee community and optimise outcomes(Reference Hugman, Pittaway and Bartolomei77,Reference Baum, MacDougall and Smith83,Reference Gallegos and Chilton84) . Certainly more research regarding refugee food security needs is critical. However, there is an opportunity to assess the existing infrastructure in high-income countries and operationalise the existing knowledge regarding refugee FI, in order to determine if iterative innovative design can better serve refugee food security needs within these current structures.

Refugees are a vulnerable population, cross-cultural research poses complex difficulties and FI is a sensitive issue, all of which makes researching refugee FI in high-income countries a challenging task. This was clearly evident throughout the reviewed studies. There were similarities in some studies which reported ‘lively and vibrant’ discussions or provided valuable cultural and contextual insight. These studies adopted a nutritional and anthropological approach, not a purely nutrition science approach. In an issue where culture is a central theme, this reflexive nutritional anthropology approach to design was more fruitful than the nutrition science based studies, as it provided greater cultural insight. To enhance this perspective, it may be beneficial for cultural insiders to be part of research teams to ensure subtle cultural nuances are not lost in translation. Further recognising the potential cultural sensitivity of FI, mixed methods design may assist in triangulating qualitative findings. This could include measures such as gathering ethnic shop sales data or using tools such as culturally sensitive diet diaries.

Limitations

A strength of this review was that it included studies from six different high-income countries and numerous sub-populations and was therefore able to synthesise findings from different settings and cultures. However, a limitation was that the majority of included studies were qualitative and cross-sectional in design. Causal factors were therefore unable to be identified. Additionally, the vital importance of cultural and conceptual nuance in relation to food security could limit the generalisability of the research findings across multiple refugee sub-populations.

Conclusion

This review identified four key themes regarding food security for refugees resettling in high-income countries. These included cultural preferences and proscriptions, individual capabilities and confidence in navigating new environments and the level of community support and ethnic affinity. The identification of these interrelated themes presents three key opportunities for policymakers and researchers. One is using these themes to adapt existing FI measurement tools, such as the HFSSM, so that they are culturally sensitive and conceptually equivalent. This would enable FI to be more effectively measured, monitored and compared, within and across high-income countries. This shared knowledge that may assist in the co-creation of solutions(Reference Gallegos and Chilton84). The second is to use the findings to further build understanding of how bottom-up capacity can be developed within communities through bridging and bonding social capital and the increased agency of refugees. Identifying effective bottom-up strategies may be an economically and culturally sound option to build food security buffers. The third opportunity is to consider how food security initiatives already established in high-income environments may be modified to be more culturally sensitive, recognise the capacity and confidence levels of refugee populations and build community connections within local refugee groups. These opportunities allow high-income countries to better develop, evaluate and modify programmes, which effectively meet the food security needs of their refugee populations.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: n/a. Financial support: Julie Maree Wood was the recipient of a PhD scholarship from Deakin University. No other financial support was received. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: J.M.W. conceived the review idea. J.M.W. conducted the search and carried out initial screening. All authors contributed to final screening. J.M.W. developed the model and wrote the manuscript. C.M., A.B. and A.W. provided critical feedback and helped shape the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021002925