Introduction

Music scholars have dedicated considerable attention to how music is created and redistributed in online platforms but have rarely addressed how and why ordinary users of social media exchange music online. This article, which is based on an ethnographic study of music sharing, puts forward the concept of ‘imagined listening’ as a new analytical tool to explain the social relationships that arise from people's interactions with online music and other musical media. Considering the interplay of users’ understandings of imagined audiences with their ideas of imagined listening, I open new avenues for research on the social value of music and the moral economies of music sharing online.

Since the advent of peer-to-peer platforms at the turn of the century, sharing and exchanging music files has propelled the expansion of online networked culture and social media platforms (boyd and Ellison, Reference boyd and Ellison2007). Digital distribution technologies have further increased what Kassabian (Reference Kassabian2013) calls the ‘ubiquity’ of music, giving an increasingly important social role to the redistribution of sound over its recording (Jones, Reference Jones2000) and diversifying the modes of distribution and consumption of music media via streaming platforms (Nowak, Reference Nowak2016). In parallel to this process, social media platforms have also played an increasing part in creating and maintaining sociality (Miller et al., Reference Miller2016), wherein music has maintained its central role for daily communicative practices. Private listening and public performance have become intertwined with music activities on social media such as live streaming, which are directed to a fluctuating imagined audience (Litt and Hargittai, Reference Litt and Hargittai2016). Before the internet's coming of age, popular music studies for a long time explored how music practices allow people to perform for others the dramatised ritual of placing themselves in a network of relationships through musical choices (Frith, Reference Frith1996). Recent scholarship addressing internet-bound practices such as curating the musical contents of personal profiles (Durham, Reference Durham and Bull2018), and as computer-mediated replacements of the living-room bookshelf (Wikström, Reference Wikström2013), have updated this interpretation, but without a clear focus on social relationships. Fandom studies that give more attention to social media (Duffett, Reference Duffett2013; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2006; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Ford and Green2013) contextualise studies of music communities online, but tend to neglect the musical practices of casual fans. Beyond the promotional uses of social media by artists (Mjøs, Reference Mjøs2012; Suhr, Reference Suhr2012; Harper, Reference Harper2019) or platform-centric studies (Burgess and Green, Reference Burgess and Green2009; Bonini, Reference Bonini2017; Durham and Born, Reference Durham and Born2022), the culture-making dynamics of music circulation online remain an under-researched area. Studies of music creativity in online platforms (Lysloff, Reference Lysloff, Lysloff and Gay2003; Cheng, Reference Cheng2012) rarely address the role of those outputs once they are publicly distributed, with notable exceptions in areas such as politics (Green, Reference Green2020). When music scholars have tackled music's so-called virality and its associated articulations of locality and gender (Howard, Reference Howard2015; Stock, Reference Stock2016; Waugh, Reference Waugh2017; Harper, Reference Harper2020), they have focused on the music videos rather than the users, and without exploring notions of collective flourishing online.

This article addresses this gap in the existing scholarship by shedding light on why people post (Miller et al., Reference Miller2016) music on social media, and in which ways music matters (Hesmondhalgh, Reference Hesmondhalgh2013) in online sociality, contributing in particular an ethnographic perspective on music audiences and their ideas of collective flourishing and moral civility. It expands the scope of recent scholarship that argues against the ‘rhetoric of digital dematerialisation’ (Devine, Reference Devine2015) and contributes to foregrounding the materiality of digital music experiences (Jones, Reference Jones2018) by advancing an anthropological theory of music as an online (im)material object of exchange within a social moral economy. I use the adjective (im)material because on the one hand, online music is indeed storable and exchangeable, and therefore retains some sort of tangible materiality as files (Horst and Miller, Reference Horst and Miller2012), particularly as objects stored in physical mass data centres that require manual retrieval via clicks in an interface. On the other hand, the circulation of digital music is precisely based on its online immateriality, and on the immaterial aspects of music listening, such as music cultures and the relationships they create. While a number of studies on filesharing (Durham and Born, Reference Durham and Born2022; Giesler, Reference Giesler and Ayers2006; Lysloff, Reference Lysloff, Lysloff and Gay2003) address the gift-like economies and values that emerge in platforms specifically designed to share music files, this article focuses on the advent of related moral economies on generic social media platforms, which are not particularly (or not only) conceived for music circulation and host a wider range of casual and non-expert users. Here I apply the concept of moral economy as it has been operationalised by Fassin (Reference Fassin2012), understood as ‘the production, circulation, and use of values and sentiments in the social space around a given social issue’ (Fassin, Reference Fassin2012, p. 441), in this case referring to the issue of online music distribution. Following Fassin's anthropological approach I consider both the political aspects of these norms and obligations, and the more specifically philosophical networks of values and affects that underlie human activities, particularly when moral economies arise within areas of ethical ambivalence, such as free music distribution in market economies and within privately owned, but cost-free social media platforms.

The first section of this article explains the relevance of imagined audiences in musical practices on social media. It foregrounds fieldwork evidence showing that in music sharing, imagined audiences are often imagined communities of listeners. In addition, the algorithmic technologies of social media and streaming platforms influence how users engage with music. Platforms create the impression of on-going activity (a kind of simulated liveness) and encourage short-span practices linked to musical ‘discoveries’, but my research participants worked with or around these affordances in the pursuit of their own social and musical goals. The second section outlines how users’ awareness of these affordances of social media in the context of the musical abundance of online spaces foster ‘cultures of circulation’ (Lee and LiPuma, Reference Lee and LiPuma2002) based on visual references to music and particular forms of ‘imagined listening’. Imagined listening here includes thinking of and remembering a piece of music and imagining an audience for its re-distribution, as well as how that audience will listen to and ultimately benefit from it. Imagined listening is then a form of online sociality based on how we think that others listen to music and on our own imagining and re-evocation of those sounds, mediated by the engagement with, and exchange and management of, visual prompts (for instance YouTube and Spotify thumbnails or record iconography) in an online interface. In the last section I demonstrate how these practices of imagined listening ultimately shape and maintain the moral economies of music sharing online, and how they are linked to understandings of civility and musical citizenship. Participants consider the exchanges of music that they frame as solidary, educational, neighbourly and gift-like as capable of transmitting abstract concepts such as happiness or beauty, and therefore practices for the common good of humanity.

The findings discussed in this article are developed from the initial interpretations outlined in my doctoral research (Campos Valverde, Reference Campos Valverde2019). The thesis discusses a much larger research project developed during 2016–2019 that includes an analysis of music sharing on social media from the perspectives of cultural and personal identity, transnational family relationships, assemblage theory, politics, safe spaces and ritual, in addition to the aspects addressed here. My contribution is inherently interdisciplinary, combining methods from digital and social media anthropology (Horst and Miller, Reference Horst and Miller2012; Hargittai and Sandvig, Reference Hargittai and Sandvig2015; Hine, Reference Hine2015; Quinton and Reynolds, Reference Quinton and Reynolds2018) with traditional ethnographic engagement, as well as theoretical contributions from popular music, cultural studies and media studies. Research insights in this article stem from extensive online and offline fieldwork and participant observation among Spanish migrants in London,Footnote 1 and participants’ insights from interviews about their musicking practices on social media. For the purposes of this paper, musicking is understood as the set of music-related practices that participants undertake online, such as posting, sharing, commenting, rating and thinking about music. Most of the ethnographic evidence deals with music files stored on YouTube and Spotify and subsequently shared to Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and to a lesser extent, WhatsApp and Telegram. Although initially I collected data merely from observing participants on social media, at a second stage of the research I used internet studies literature to think through concepts that summarised some of the dynamics that I was observing. However, this form of armchair anthropology also proved to be insufficient. I complemented this observation and interpretation work with the ethnographic face-to-face part of the study, with a view to understanding participants’ musicking practices beyond my distanced theorisations. Conversations at this stage, and later, recorded interviews, yielded important contributions. Particularly useful was a specific face-to-face interview technique that I employed, printing screen-captures of participants’ online activity and asking them to discuss their reason for sharing the music shown. Through the use of this technique, I attempted to encourage participants to reflect on the reasons for these postings in depth, and to think of their own posts from a third-person point of view, in contrast with interview techniques that favour participant-led tours of their overall social media activity (cf. Why We Post, 2016). To protect participants’ anonymity, their contributions are cited here with pseudonyms, and the original text from their posts is not shown but summarised. The evidence presented in the following sections shows this mixed-methods approach, weaving fieldwork notes, social media screen-captures (including interface images) and interview quotes, with theoretical contributions. The research design for this project was also open-ended from the start, and I did not select a specific music genre or scene. Instead, I collected fieldwork data from diverse music cultures to infer wider social practices and understandings: the insights presented here on the social dynamics and the meaning of music circulation online are applicable in multiple contexts. That said, conducting immersive ethnography with Spanish migrants allowed particular insights into musically mediated relationships when these are inherently cosmopolitan, and into online sociality as practised citizenship. In addition, the mixed method employed to recruit participants also influenced the material collected. I promoted my study in person with other Spaniards and by handing out flyers, which I also put in strategic locations around London where Spaniards regularly gathered in large numbers, particularly nightlife venues. However, most participants recruited appeared to have found out about the study via the posts that I shared on Facebook. This strategy seemed to involuntarily recruit more women participants.Footnote 2 In this way, both the methodology I employed and the community investigated played a significant part in developing the broadly applicable theory of imagined listening outlined here. The online musicking practices of migrants therefore illustrate how music media is a cultural object of exchange for the wider social media user community.

Imagined audiences and algorithmic mediation

Initially, the participant observation phase of my research appeared to demonstrate the relevance of cultural studies to understand online musicking. Looking at the participants’ social media profiles, it seemed that interpreting musical activity on these platforms primarily as a social theatre, or as a performance to articulate cultural identity and accrue cultural capital, could explain why people share music online. However, this subcultural perspective soon proved to be limited in a context of migration, owing to the ways participants understood their audiences and managed them online. During our first conversation, participant Sue made clear that her Facebook posts about British metal were addressed to her family back home and had no local objective or audience. Although she admitted that her music sharing was a way to transmit her passion for metal to her children and keep them ‘on the right musical path’, she did not intend to articulate these relationships beyond what she perceived as a close albeit physically distant social circle. Even when she posted about attending a concert or music event, this was still directed to her family, and not to other attendees or fans. Other participants had similar understandings of the audience that aimed to generate the illusion of family togetherness, hardly fitting the cultural studies approach mentioned earlier. Sandra shared hard rock songs and concert videos mostly thinking about her sisters in Spain, explicitly stating that she had lost hope in making friends locally via shared music taste. Even for participants that were musicians, accumulating followers or attention did not come up as a crucial motivation for sharing. As a singer, participant Anabel was more concerned about showing her knowledge of soul, gospel and jazz among her contacts in Spain than to promoters or musicians in London. Even participants who were more focused on their UK social lives and local taste-making – Cynthia, Daniel or Javier – were primarily concerned with recreating a Spanish microcosmos in London loosely aggregated around music, rather than using this cultural capital to climb up any social ladder in the UK. Thus, in my case study, users appeared to address audiences or social groups strongly defined by previous personal ties and that did not fit ideas of local, class-bound subculture. The liminal character of migrant lives questions the fitness of typical cultural studies’ approaches in contexts of economic deprivation, where support from and maintenance of firmly established and familiar relationships may become safer social investments than the often-unattainable expansion of local ties or capital through music taste. Indeed, fieldwork showed that for Spanish migrants, ‘achievements of wealth and status’ – and in this case study, displays of identity or music knowledge – ‘are hollow unless they can display them before an audience living elsewhere, in the authentic heartland of their imagined collectivity’ (Werbner, Reference Werbner2002, p. 10, my emphasis). But more than arguing in favour of the distinctiveness of migrants’ online practices of sharing, these initial observations indicate that researching migrants’ online musicking highlights that social media users often do not address their local relationships when they are online.

Although this specific group of participants emphasised these different understandings of intended audiences back home, ‘imagined audiences’ (Litt and Hargittai, Reference Litt and Hargittai2016) are present in most communication in the online mediascape, not just between migrants. Since social media platforms only supply limited resources to users to manage their reach, these musicking activities are directed towards an imagined audience, as the real audience cannot be known. These imagined audiences can be targeted, for instance a specific person or group of people with whom the user has a previous relationship. They can also be abstract, understood as mental conceptualisations of users of a given platform or online audiences in general (Litt and Hargittai, Reference Litt and Hargittai2016). In this second definition of the concept, imagined audiences in an online context are similar to the imagined communities described by Benedict Anderson (Reference Anderson1991), as their existence is largely based on the mental imagining and collective sense of belonging of their members. Indeed, participants confirmed that in social media the audience can be redefined by active users at any one time, depending on who music is directed to, or received by. Jasmin, another participant, expressed well this idea that the audience is imagined by the person posting something, to the extent that the receiver may not have access to the content, or that the target audience can include multiple groups:

that person does not have to [necessarily] be on my Facebook. For me it is important to post it because that's how I feel in that moment. (…) That's why I post many songs. (…) Also because I find the music interesting, so that my friends can listen to it. Jasmin October 2017.Footnote 3

As Jasmin's statement hints, imagined audiences on social media are then mental constructs and systems of social understandings, assembled through the online practices of music circulation themselves, more than established or identified networks of communication. In this sense, imagined music audiences are also imagined communities of listeners with whom users want to share music. Both Daniel and Cynthia evoked this idea; they reported sharing music to communicate with these imagined collectivities, which appeared loosely but not exclusively to be made up of their social media contacts:

I don't post it thinking about anyone in particular, because I don't know who is going to receive it. I can imagine who will get it, because I know who I follow [on Twitter] and who might like it, but I can't know for sure. Daniel, January 2018

I am sharing it with the people that are supposedly there (…). Cynthia, January 2018

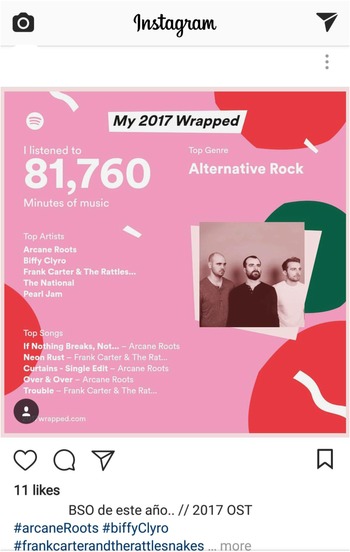

These ideas about imagined audiences or imagined communities of listeners are strongly influenced by algorithmic technologies in two ways. On the one hand, algorithms create and shape audiences without human intervention, including through what I call ‘mediatised liveness’, namely the illusion of non-stop human activity and the constant re-creation of new audiences for music through the strategic placement of songs and music videos in the interface.Footnote 4 As Daniel states above, posting music implicitly admits that one does not know where it will end or who will see it because of algorithmic mediation. On the other hand, people may share and circulate music precisely in response to these algorithmic prompts, extending further this imagining of audiences and contributing to the liveness of platforms. For example, at the end of 2017, Spotify offered users an automated summary of their listening for the year that identified favourite songs, artists and genres. Sandra's ‘Spotify Wrapped’ summary (Figure 1) certifies her as part of the audience for a set of bands by creating a visual representation of her past listening practices that can be shared and reposted. At the same time, by sharing that playlist with others, Sandra contributes to re-creating and expanding that audience herself. In other words, algorithms constantly re-create audiences, but so do people.

Figure 1. An Instagram post shared by Sandra with her 2017 ‘Spotify Wrapped’, in response to an interface prompt.

In addition, imagined audiences are always in flux because algorithms encourage short, asynchronous interactions around music media rather than long-term engagements with pieces or albums. These temporary or even ephemeral engagements with music are also directed to varied music genres, promoting classifications by mood and narratives of discovery (Morris and Powers, Reference Morris and Powers2015), to the extent that only specific timeframes of engagement with music and audience types are algorithmically possible (Hills, Reference Hills2018). However, as participants mentioned, once again people may further increase these momentary practices through their own activities to cope with algorithmic inadequacy and to create a greater experience of agency, ownership and flexibility in listening practices (cf. Hagen, Reference Hagen2015, Reference Hagen, Nowak and Whelan2016). For instance, Fernando highlighted how Spotify's algorithm can discover hardly any Western classical music that is new to him. Because he knows which pieces, interpretations and recordings are his favourites, Spotify's attempts to turn him into a temporary fan of a particular piece are unsuccessful. At the same time, Fernando admits that he has to limit his interaction with Spotify in order to avoid further feeding the inadequate algorithm. He only listens to particular albums and ignores platform playlists, thus becoming himself a momentary online listener. These self-imposed fleeting practices would also help participants avoid ‘filter bubbles’ (Pariser, Reference Pariser2012) that would further narrow their listening habits, although they did not articulate these biases in such terms. Javier, a participant with an eclectic music taste, expressed frustration with the limitations of recommendation algorithms on Spotify:

Because the first songs that I listened to [on Spotify] were metal or rock, now everything that it recommends me is like that, and I don't always feel like listening to that genre. That's why I only use it every once in a while. Javier, December 2017

These conscious forms of self-limitation driven by algorithmic technologies are relevant to this discussion because they shape how participants think about the audience for their own posts and the music that they share. If one's own engagement with music online is sporadic or temporary, it is safe to assume that others will act the same. If I know which music I like, so do others. Thus, while both algorithmic and human practices may contribute to an idea of non-stop music liveness, where new audiences are incessantly re-created by people and machines, users are conscious that this is not the case, and that people engage with music online within certain limitations. Cynthia, who can post as many as 10 songs per day at times, and who is teased for sharing too much music by her friends, accepts these patterns of temporary engagement:

It has happened to me, that from people that hadn't posted anything [on Facebook] or commented [on my posts] for a while, suddenly one day I log in and I see 20 likes to 20 different posts. Cynthia January 2018

More importantly, the human and machine dynamics outlined in this section mean that momentary forms of musicking and imagined audiences are normalised aspects of musical engagement in this mediascape. In light of this I argue that music circulates on social media because users imagine that there is an audience, as this is one of the basic principles of liveness in diachronic online communication. Specifically, an imagined audience that interacts with music online within the limitations of algorithmic and human liveness, discovery culture and fleeting engagement.

Ubiquitous and silent music media: imagined listening in the 2.0 mediascape

Worthy of consideration here is how momentary musicking practices, imagined audiences and algorithmic liveness are also both cause and consequence of the ubiquitous presence of music online (Kassabian, Reference Kassabian2013; Fleischer, Reference Fleischer2015; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Werner, Åker and Goldenzwaig2018), and how they foster specific new forms of listening. Participants accessed music and other music-related media easily and recirculated it on their profiles, without any cost beyond an internet connection or smartphone contract, thanks to ‘ubiquitous computing’ (Kassabian Reference Kassabian2013, p. 1; Mazierska et al., Reference Mazierska, Gillon, Rigg, Mazierska and Mazierska2019; Prior, Reference Prior and Bennett2015). In my case study, sharing music happened mostly from streaming platforms to social media profiles on smartphones, without requiring specific locations or listening habits.Footnote 5 Among my participants this ubiquity of online music gave rise to understandings of music as a continuous, ongoing stream like radio or domestic utilities (cf. Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Werner, Åker and Goldenzwaig2018; Negus, Reference Negus2016). However, here I argue that these understandings of music as a ubiquitous utility foster contradictory musicking practices. On one hand, music is socially relevant in online communication because it is always available, easy to use, and textually rich. On the other, its ubiquitous presence is something taken for granted by users, so actual engagement with music is not a priority. In fact, the ubiquity and availability of music media favours its taken-for-grantedness. Among this particular group of participants, users do not think of music in terms of commodity precisely because it is almost always accessible. Sandra said:

To listen to music, I don't download anything anymore. I listen to everything on streaming. (…) One day the internet will end, and I will kill myself (laughs), because I won't have any music anywhere (…) Sometimes there is a video on YouTube that you really like, and you think: ‘I should download this.’ But you don't. (…) You think: ‘they won't take it down’ but then they do! (laughs). (…) You take it for granted. Sandra, November 2017

As Sandra indicates above, participants considered storing music to have become a time-consuming and resource-heavy luxury in this mediascape of ubiquity, so streaming was for them a dynamic online archive, even if one not fully under their control. Sue, for instance, explained that because she lost all her records in her divorce, she cannot ensure that her children inherit a good material music library without considerable investment, and thus posting a song for them every evening somehow replaced that family archive.

More importantly, this understanding of music's ubiquity and taken-for-grantedness has the potential to dissociate listening from the actual moment when a song or music video is first encountered online. Participants admitted their own struggle to keep up with music releases, friends’ and platforms’ recommendations, and other musical paratexts, and they were aware that their own posts could get lost in the ever-changing algorithmic maze. Cynthia's friends often mentioned their inability to listen to all she shared owing to her excessive music posting, and Sandra's used similar language to describe her sharing of information about Pearl Jam. Additionally, in certain contexts the face-to-face recommendations of friends and family may carry an aura of authenticity and thus be more appreciated than online recommendations, as Johansson et al. (Reference Johansson, Werner, Åker and Goldenzwaig2018) conclude. Cynthia explained that her friends sometimes recommended songs to her that she had already posted but they had not seen, her posts being ignored. However, recommendations that Cynthia made to her friends in person were taken seriously. Consequently, participants were empathetic to how others managed their time and attention to deal with the sheer volume of music recommendations, and were aware of the difficulties experienced by imagined audiences in seeing and engaging with their music posts. Considering this evidence on ubiquity and taken-for-grantedness, I argue that music is so abundant in online interaction that, paradoxically, most of its circulation is silent. Playlists remain unheard and music links are not clicked, because users are unable to listen to all of the music that they are exposed to by friends, family, and algorithmic recommendations:

In general people do not react much to songs (…). Maybe most of them don't even listen to them. But that's not only for me. I have seen that for other people that share music; they almost never have reactions. I think that on Facebook people are just scrolling down all the time and when they see something that requires stopping and listening, they don't even check it. (…) When I share something on Facebook I know that people are not going to listen to it. I give people the chance, but I know that they are not going to listen to it. Javier, December 2017

If someone wants to listen to it and likes it, fine. If not, so be it. (…) because everybody has their [Twitter] timelines full [of information], so the probability [of someone listening] is low. Sandra, November 2017

I try not to be annoying with music, (…) because just as I usually do not click on the links from other people, I understand that they don't do so with mine. (…) for instance, if I post five links, maybe they only click on one. The rest, they either remember them [the songs], or they don't care, or they are in a context in which they cannot listen to them. So, I don't share them with any intention, because I put myself in their place. Teresa, October 2017

From this evidence it follows that listening does not necessarily happen when someone sees a music post or tweet, and that listening is somehow a secondary motivation to share music with others as there is a mutual understanding of this ubiquity of music online. The concept of silent music thus makes perfect social sense for these participants in a technological context of abundance. It is not too much of a leap to say that thinking about, or testing whether it is worth, sharing music as Javier and Teresa make explicit here, is in itself a key driver of this practice.

However, fieldwork confirmed that just seeing the name of a song or a thumbnail preview may be sufficient to understand the reference, message, or mood intended, and even to imagine the piece of music being circulated. To an extent, music circulates as a visual object that evokes sound. So, even unheard, these visual prompts help to articulate a message. Statements from participants thus demonstrated that the semiotic capacity of music media is indeed a result of its visual and sonic aspects, as Goodwin (Reference Goodwin1992) points out, but in social media this meaning making may happen through practices where music may not be listened to at all:

(…) I posted that Cindi Lauper GIF [soundless moving image] from ‘Girls Just Wanna Have Fun’ (sic) in response [to a conversation about feminism] (laughs) … (…) but you fill it in with your mind (laughs) (…). In an imaginary way, you sing the song for yourself in your mind (…) this is because some songs are so iconic. Sandra, November 2017

Sandra's references to imagination and singing to oneself in one's mind reveal the crucial aspect of exchanging music on social media (in comparison for instance with peer-to-peer tools): the visual interface enables users to experience music as a product of memory or imagination, more than as a primarily acoustic feeling. Indeed, if archival practices and ‘tissues of quotations’ (Barthes, cited in Olson, Reference Olson, Cotton and Klein2008) are the foundational and ubiquitous forms of presenting and producing music online (for instance on Spotify and YouTube), the circulation of music as a visual object evinces its character as a reference to stored sound. This use of music media as a reference to known sounds goes beyond practices of selective inattention in which music may be used as background noise. In contrast with musicking practices of the 1990s that generated a sort of split attention or double musicking – such as bars that played music videos on screens while playing a different song over the PA system – on social media there may be only one sound evoked at a given time, a video thumbnail or a gif as in Sandra's example, but one unheard nonetheless. Ubiquitous music in offline environments generated a ‘ubiquitous mode of listening’ (Kassabian, Reference Kassabian2013, p. 10) related to the attention economy of shopping malls (Sterne, Reference Sterne1997) or bars. Here I argue that ubiquitous music in visual online environments (characterised by imagined audiences, mediatised liveness, algorithmic mediation and momentary musicking) generates imagined listening (and not only lack of listening), which is related to the attention economy of social media spaces.

Imagined listening, then, is the emerging mode of listening characteristic of online musicking, and the tacit cultural norm that governs music sharing and circulation online. Imagined listening here is understood as a form of online musicking and sociality based on how we think that others listen to music, and on our own imagining of those sounds, mediated by the exchange of visual prompts in an online interface. Imagined listening practices are the mental processes of the user who posts a piece of music media helped by a mental evocation of it, and imagines how others will or could listen. They are also the mental practices of the audience as they remember and evoke known songs and sounds from visual cues in the social media interface. As Sandra said, the memory of certain tunes sparked from a visual prompt can be sufficient to engage in musicking, so a YouTube or Spotify thumbnail preview on a Facebook or Twitter feed is indeed a reference to stored sound, and enough to activate this mode of listening.

This is also the case for other musical activities on social media, such as ranking or voting, which also spark memories or imaginings of songs. Figure 2 includes a representation of a jukebox featuring eight metal songs, along with encouragement to readers to vote (drop a coin) for their favourite. Also included is a comment from Sue, who votes for the track by Iron Maiden. Here I argue that activities like this one summon fleeting musical memories of the songs in question, even when they do not involve listening to the recordings themselves, simply because the interface provides a visual representation or evocation of listening, in this case at a bar or venue. However, for many contemporary music fans the equivalent iconography of on-demand music would not be a jukebox but a YouTube or Spotify icon. Therefore, every time a young(er) individual encounters a preview of a song in their social media feed, they experience a reactivation of this mental evocation of music. They also understand the visual prompt as equivalent to the social practice of playing a song in the jukebox: in a public social space where people are hanging out, some individuals explicitly show (through iconography in this case) what music they are (perhaps mentally) listening to.

Figure 2. A Facebook comment by Sue, engaging with a visual representation of playing a song in a jukebox.

As the statements above suggest, when practices of imagined listening do not develop through musical memory, they do through imagining that the audience is listening, or how it will listen to a posted song in an unspecific future. Sharing music media makes sense because users imagine specific or abstract groups of people who will not just see the musical image and mentally evoke the song, but will also listen to it (or even further engagement such as watching and listening in the case of music video) at the point of reception or later.Footnote 6 This is ultimately why participants share and circulate songs and music videos:

Because I am optimistic! (laughs) …, and I think that at some point people will remember and say: ‘let's listen to that song that [Cynthia] posted’. I don't know, … it's leaving the door open, so if they remember, they can have access. Even if they don't listen to it in the end. (…) they don't have time. (…) I don't care about getting home and finding that I don't have a single ‘like’. I know that someone is going to listen to it, (smile) … I know it is a strange thing (laughs) … (…). I think that it goes like this: thinking that someone is going to watch it [music video], someday. Cynthia, January 2018

These practices of imagined listening also happen in more active and critical ways than the apparent abandonment of agency derived from accepting the lack of control over who listens to songs. The tacit rules of imagined listening become prominent when users acknowledge the social uses of platform affordances – such as private messaging and tagging – and the conceptualising of imagined and actual listening as two separate practices:

I am not thinking about anyone in particular (…) otherwise I would tag them. Daniel, January 2018

I don't want to bore people, so sometimes I send them music directly and I don't share it with everybody. Elisa, October 2017

With these statements participants suggest that although some may tacitly be imagining others listening when they post a song, they also instantly recognise this mental construction, because when they really expect listening, they choose different forms of communication (such as tagging and instant messaging). In this sense, online musical life operates at different intensities (‘scalability’ per Miller et al., Reference Miller2016: 3). Through this micro-management of the attention of social media contacts via different ways of music sharing and listening, users decide how to engage with others and thus shape their social relationships. If ‘online listening constitutes a recognition of others’ (Crawford, Reference Crawford2009, p. 533), listening and responding at length require deeper engagement expected from close ties, while rating only or not engaging at all may be used for acquaintances.

Similar kinds of imagined listening – imagining oneself or others listening in the past or in the future – take place when users share music via compiled playlists on streaming platforms. Daniel and Sue explained that preparing a playlist or a list of posts and sharing it with others before attending a concert or a musical not only entails learning the songs in preparation for the live shows (for which perhaps the playlist is a temporary tool), but is also a form of mental anticipation that involves imagining oneself and others listening to those songs live in a specific future. Sandra and her sisters shared ‘guilty pleasures’ playlists with each other on Spotify to evoke their past collective experience of growing up together, while knowing that they would not be listened to that much. This evidence suggests the use of online music media as ‘dynamic memory’ (Ernst, Reference Ernst2012) that enables processes of past and future nostalgia, where remembering is used as an audiovisual aesthetic that enables social interaction around sound files (or visual prompts to sound files) and their imagining. Imagined listening as an online mode of listening is then also related to the existence of ‘unlistened’ playlists in streaming platforms, as a form of musicking that entails a sort of expected engagement of oneself and others with music, as well as our own re-evocations of musical memories (including the future evocation of those memories in live shows). Similarly, these playlists and their associated forms of imagined listening equally represent desired expectations about our personal relationships, in the same way as with previous formats such as the mixtape (Rando, Reference Rando2017). This is quite explicit in the case of migrants and their desire for family or friendship togetherness, but nonetheless applicable to internet users at large as they communicate with imagined audiences.

The paradox created by the ubiquity of music media, whereby it does not generate collective listening, could be read as a sign of the absence of social connection in online spaces. Participants’ statements also suggest an acknowledgement of speaking into the void, or at least an ambivalence about the impact of their musical practices. Although I noticed that some participants’ playlists did not have any followers, fieldwork did not show a clear pattern for reactions or feedback to music content. Sandra explicitly mentioned that her music postings also come from a place of loneliness as a migrant living in a small commuter town, without any close ties or other music fans to talk to. She also highlighted how posting during a concert can be a way to connect with other attendees online, in the absence of in-person interaction. In other words, once the emptiness of social life is accepted, participants find that online musicking is an imaginable, albeit imperfect, remedy.

Imagined listening thus responds to the mediascape of ubiquity by prioritising cultural aspects of music media other than their sounding playback. In a similar vein to what Madianou and Miller (Reference Madianou and Miller2012; also, Miller et al., Reference Miller2016) describe with the concept of ‘polymedia’, I argue that when the focus is no longer on accessibility, which is taken for granted, people's attention is drawn to choices about different avenues for sociality. As Frith points out, the meaning of a musical experience, including that of listening, appears as a social matter by defining imagined social processes (1996, p. 250 my emphasis), even if people might perceive meaning as a value intrinsically embedded in the music itself (Frith, Reference Frith1996, p. 252). In other words, the different kinds of imagined listening shown above, based on musical memories and on imagining oneself and others listening in the past, present, or future, provide resources to work on diverse forms of social culture-making.

The moral economies of music circulation

I turn finally to the macrosocial aspects of this silent exchange of music. The moral economies of music sharing and the values that users accord to music further purvey arguments in favour of understanding imagined listening as the basis of online musicking cultures. The evidence presented in this section demonstrates how participants in these moral economies ‘make choices based on ethical principles (…) reflecting but also going beyond the roles assigned to them (…) giv[ing] life to institutions through their ethical questioning and affective responses’ (Fassin, Reference Fassin2012, p. 441). Fieldwork revealed that three principles govern the moral economies of these silent spheres of music circulation: solidary fandom; exchange and gift-giving rituals; and musical civility.

First, participants engaged in practices of what I call solidary fandom: musicking activities where the user undertakes the role of a grassroots promoter, oriented towards helping emerging artists. By recirculating music and other media and promoting the shows of emerging artists, users hope to help them expand their fan bases and achieve greater recognition, or in some cases, strengthen the presence of the band in their immediate social circle. Within these practices of solidary fandom, there are two further aspects of its moral economy to consider. On the one hand, participants are conscious of the relative impact of their musicking practices in terms of data traffic within their social media contacts. Participants understood activities oriented towards helping emerging bands or meeting less-known artists as a positive potential of social media communication, which would redress a perceived corporate control of music.

(…) even if I am not a mass medium with a huge audience, if I put something on the spotlight I will generate more audience at some level for that artist, and maybe more money. I am conscious of it and I try to generate interest for particular artists. (…). Anabel, November 2017

[I have shared it] [w]hen I have found an artist that was very good but was not very well-known, or almost completely unknown, on YouTube. (…) with the idea that the guy deserves to be heard, and that he should be more popular. (…). Javier, December 2017

On the other hand, practices of solidary fandom confirm once again the reflexive character of these online cultures. Participants’ awareness of the mediascape lead them to focus on the positive impacts of these practices on their personal lives and on the lives of their immediate social circles.

For small bands these little things are useful. The more people post about it and the more you publish on your social networks, the more they become known, which is ultimately free advertising. If the band is worth it, it doesn't cost a thing to help them. (…) I know that Pearl Jam does not need my support (…) Sandra, November 2017

(…) with some bands it doesn't matter if you promote them. I can like Iron Maiden very much but even if I share the link to their website, what is it going to do for them? (…) But during Resurrection [Festival] there were many small bands that weren't known at all. In those cases, yes, I like to put (…) an official link so they get some traffic. Because it's a way of thanking them (…) Daniel, January 2018

(…) you are not going to send a message to Metallica like ‘hi, what time's the show tomorrow?’ If it's a minor band, ok. Because you attend a concert with other 300 people and at the end you can have a beer with the band or whatever. But with popular bands no, it's absurd. (…) Just because you send them a message you are not going to become mates. Rose, October 2017

Rose and other participants thought that meeting an emerging artist would more likely lead to a meaningful social interaction, thus orienting their musicking on social media to those possibly richer socialities. They were also sceptical of interacting with the professionally managed social media accounts of famous artists, and as Daniel and Sandra highlighted, while their music sharing might be an effective promotional tool for artists without a considerable following, they considered it unnecessary to further promote famous artists. If anything, they considered it unfair to give more media space to established acts, again understanding their actions to redress the power imbalance between famous and emerging artists. Rose went so far as to say that any social media interaction with famous bands was pointless, a reaction that calls into question whether online fandom practices can be understood as the cultivation of ‘the perception of accessibility and proximity’ (Duffett, Reference Duffett2013, p. 238). As Sandra articulates above in terms of cost, participants give different moral value to these instances of free ‘fan labour’ (Baym and Barnett, Reference Baym and Burnett2009; Terranova, Reference Terranova2004), thus socialising and helping to create a fairer music market are privileged over the potential access and benefits to famous artists. These statements also confirm a continuity between the underground-oriented musical dynamics of MySpace in the 2000s and those of current social media platforms, driving people to invest in social relationships with emerging artists.

An emphasis on positively impacting lives is even more pervasive in instances where music exchange is a kind of gift giving – and here we arrive at the second moral principle of online music circulation. Sharing music constitutes a kind of gift economy: that is, a form of music exchange and relation of mutual obligation between online ties involving social-media-specific ways of giving, receiving and returning gifts. Malinovski's (Reference Malinowski2002 [1922]) foundational text on gift economies describes the Kula Ring, an exchange circle and ceremonial trading system where participants from different islands trade altruistic gifts from others and contract mutual obligations to reciprocate. Miller (Reference Miller2011) offers a recent discussion of this kind of gift economy on social media that he calls ‘Kula 2.0’, in which textual sociality and communication contribute to the trading circle between an internet-connected archipelago of users. My contention here is that musicking activities that circulate music between social media and streaming platforms are also culture-making exchange circles, developing as an aggregate of smaller gift-like exchanges between friends, families and acquaintances:

(…) the same way you share information or opinions through Twitter, you share music with the same purpose: that the other person, that you think would like it or could be interested, receives it. (…) In fact, when I put something like ‘for my girls’ or ‘for my friends’, for me they are like gifts. (…) They are like small moments of happiness that you share with people. (…) Not thinking about someone in particular or a specific moment, you simply say ‘I am going to share this’, like a gift, ‘I am going to send a gift to the world, so that someone sees it’. Teresa, October 2017

As shown in this statement from Teresa, and others cited above from Javier, Sandra and Cynthia, even if the lack of feedback casts doubt on the impact of these practices, these music exchanges still work as gift economies. The existing imagined audience facilitates the understanding of these exchanges as ‘gifts of co-presence’ (Miller Reference Miller2011, p. 212), based on previous understandings of music as gift and the mutually understood need to reciprocate. As Baym (Reference Baym2018) highlights, fans feel the moral obligation of sharing the music they like to connect with others, again suggesting that forms of music exchange that predate social media or stem from peer-to-peer practices (Born and Haworth, Reference Born and Haworth2018; Giesler, Reference Giesler and Ayers2006) still govern the exchange of music to an extent. However, while some gift economies focus on obligations between particular persons (or a community of committed fans), a key aspect of the musical exchange I am considering is the emphasis on moral value and general collective benefit. Similarly, while both Miller (Reference Miller2011) and Chambers (Reference Chambers2013) posit that meaning-making activities of online sociality involve ritualising relationships through the exchange of cultural artefacts and publicly proclaiming friendship, here I argue that exchanges of music take place as a series of semi-public ‘prestations’ (Mauss, Reference Mauss2002 [1954]) aimed in a general way at a user's imagined listenership, where explicitly stating friendship is only secondary to an abstract idea of collective benefit.

Instead of highlighting a particular relationship, in my case study it was easier to notice this moral grounding of collective benefit in time-specific music exchanges, where people effectively salute an imagined audience or each other at a specific time of the day, through posting a piece of music or musical iconography. For instance, participant Diana often shared music on Facebook with a ‘Good morning’ caption (Figure 3), to wish others a good day with a feel-good song. But in this case her Facebook friends are almost a proxy for humanity at large. Sue also posted music every evening with the caption ‘Good night’, sharing songs that were important to her as a bedtime kiss to her children before they went to sleep. Many other participants also greeted friends and family at specific moments of the week with time-specific music, such as Friday evening playlists. In other words, when a particular relationship was highlighted, it was also a time-specific exchange ritual.

Figure 3. A music salutation with the caption ‘Good Morning’ posted by Diana on Facebook.

Often, these exchanges were articulated through collectively sacralised pieces of music. That is, to salute others, people use music already part of previously existing social conventions such as ‘good vibes’ or ‘club music’. If music sharing helps in managing different levels of relationship closeness, sharing an iconic track that most will understand is an efficient way to salute many. Thus, music has an essential role in these exchange rituals both because participants consider it as a valued element in itself (a present), but also because it furnishes a familiar accompaniment to daily human routines, very much as happens offline. Music media are so culturally rich that they can confer online norms and etiquette, and can be used to maintain customs and expectations about how one should feel on a Monday morning, or what one should be doing on Friday evening, but also more generally about reciprocity and online sociality. However, these practices seem slightly more targeted to specific groups than the jukebox-like sharing explained above, and in consequence more personal verbal messages preceding music iconography give important moral weight to music sharing.

The ethnographic examples in this article thus show that on social media, musical cultures of circulation are ultimately oriented towards constructing morality through musicking. Social media practices can be ‘a moral activity in and of itself’ (Miller et al., Reference Miller2016, p. 212) in the sense of being intrinsically social, and musicking relationships model ‘ideal relationships as the participants in the performance imagine them to be’ (Small, Reference Small1998, p. 13). Therefore, music sharing activities on social media are users’ put-into-practice ideas about what music and society are, and ideally should be, governed by the principle of imagined listening. Indeed, fieldwork showed that a third (and last) overall aspect of these music cultures of circulation is their moral economies of civic duty, and the activating of civic discourses. In other words, in online social life a form of musical civility is put in motion when the circulation and exchange of music are used to articulate moral values and understandings of ideal forms of civil society (online and offline), and to contribute to collective forms of human flourishing.

These civic narratives make social sense because participants saw their musicking activities as a form of spreading not just musical gifts, but more abstract concepts such as happiness. Participants’ statements revealed that imagined listening also implied imagining that the music posted generated happiness or good feelings, and therefore, posting music rendered a service not only to specific people but also to humanity at large:

(…) (Y)ou can imagine the face [does happy face], but [online] it is a bit impersonal. However, I think that if they receive it as I do, like ‘wow what a great find’, then I think that someone else is having the same reaction somewhere else. So, it is a little bit that, imagining it [the happy reaction]. Cynthia, January 2018

I post things that have provided me some sort of benefit, so that others can also have it. (…) So, I think: ‘people would like to see this’. Like that: ‘people’, everybody, humanity. Diana, October 2017

It's quite rhetorical. I can't say that it has a specific objective. The general feeling that I have when I share any kind of song (…) the purpose would be the same as for sharing a beautiful picture: to share beauty, good feelings. That is what is behind anything I share. (…) It's like … ‘this song is awesome, you are welcome’. I know that they are going to be thankful for it. Javier, December 2017

Indeed, as these statements and the example by Diana above (Figure 3) show, sharing songs understood as qualitatively good or capable of creating good feelings and transmitting beauty also mobilises a sort of moral exchange of music: circulating audiovisual objects encapsulating ideas of morality and values is a civic practice that shows human understandings of reciprocity and redistribution in social life, in the same way as Venkatraman (Reference Venkatraman2017) indicates for memes. This belief in the power of music circulation to achieve these civic publics of collective flourishing expressed by participants, articulated around concepts such as happiness or benefits for humanity, appears as a middle ground between the spiritual understandings of karma that Venkatraman outlines, and a completely secularised idea of musical civics. On the one hand, these musicking activities develop in a ritualised, faith-based system of exchange with specific codes of public behaviour that is believed to improve social media communities and thus society at large. On the other, rather than spiritual beliefs, these music exchanges are based on the belief in a universal and positive value of music when it is sent into the exchange circle, whatever the style or artist. As Johansson et al. point out, ‘if music is a daily companion and is as important as breathing, it may be seen as a common good’ (2018, conclusion). In any case, these statements once again highlight that even if the song may not be listened to at all, practices of imagined listening are the crucial elements that sustain the emergence of new moral economies of exchange: imagining the positive effect of music on others and society governs music sharing online. All these principles evoked by participants – of solidary fandom, gift giving, courtesy, morality, abstract happiness and rules of online behaviour – contribute to this moral economic system of music circulation online. Reiterating the insights stated in the previous sections, migrants’ practices in social media reveal the importance of abstract understandings of the audience, to the extent that music is thought to be shared with humanity at large, for the benefit of everyone.

However, here the apparent righteousness of this music sharing entails contradictory moral principles. One the one hand, users’ altruistic attitude does not expect gifts in return: the statements from Cynthia and Javier show that imagining the potential benefit of that music on society or how others will be happy or thankful are the central elements of this culture of music circulation. Yet participants’ statements also show ambivalence about the impact of their practices as rhetorical social devices. On the other hand, this music exchange could also be interpreted as a way to reproduce normativity, particularly in its more structured manifestations as time-specific salutation and moral meme. After all, music circulation in those formats seeks to establish quite conventional codes of behaviour in a loosely regulated social space: politeness, scheduling conventions for work and leisure, sweeping ideas of universal happiness or good music, and so on. Here I concur with Venkatraman (Reference Venkatraman2017) and Costa (Reference Costa2016, p. 79) in that social media can be quite a conservative social space. With the exception of solidary fandom practices, the ostensibly utopian moral economies outlined in this section are rather Western-centric, and definitely not cyber-punk.

Despite these contradictions, ubiquity and imagined listening are thus far from creating an obstacle to music circulation or devaluing music online. On the contrary, they are part and parcel of the emergence of these new moral values and norms about musical civics that foreground the relevance of music online. The practices outlined here try to recover precisely sociality-centred forms of musicking with a focus on collective impact. They confirm that human agency is not at all lost in a highly commodified and mediated context such as social media. More importantly, they highlight that to answer the questions of why people share music on social media, and why music matters online, emergent forms of musical citizenship offer a compelling argument. Instead of conceptualising the contemporary mediascape as a place where music has lost relevance and been increasingly commodified – as if algorithmic and internet technologies could have deprived music of its aura – I argue that music cultures and their iconography are ingrained in social life to such an extent, and its cultural references are so widely shared and appreciated, that they might not even need to be listened to, and that they are thought time and again as articulations of civic values.

Conclusion

In this article I have demonstrated how the musicking practices of migrants on social media illuminate the importance of online music as a cultural object of exchange. In a mediascape characterised by musical abundance, momentary engagement and algorithmic technology, practices focused on imagining an audience and how they listen to, and benefit from, music, highlight the social relevance of musicking in online culture-making and sociality. Through posting, sharing and circulating music online we not only visually evoke sound to communicate with others, but we also create our own imaginations of others as potential listeners, and put to work personal memories of sound as imagined listening experiences within ourselves. I have also presented evidence to demonstrate both that imagined listening is the cultural norm that drives music sharing and circulation on social media, and that it sustains emergent moral economies of music exchange that go beyond online spaces into our material lives. This not only opens new avenues for research on musicking and listening practices, but contributes to studies that bridge online sociality with the materiality of digital experiences. Through the management and redistribution of music online, we aspire to re-enact groups and togetherness, and influence and change our social circles for the better. Music is circulated on social media because users consider it a practice for the common good in reference to the specific environment of social media, but also in general societal terms. In this sense imagined listening forms the basis of the moral economies of music sharing online, but in turn the moral economies further reinforce practices and bring home the material applications of imagined listening. In online spaces, music exchanges influenced by understandings of mutuality, economic interests, moral aspirations and desires of social change collide. Here I have proposed an approach that considers the conscious agency of users in this mediascape and their unyielding tendency to make online experiences more human, particularly in contrast with techno-deterministic approaches and arguments about virality. Far from being cognitively damaging, excessive or virally inhuman, online music is shared as an act of musical civility and citizenship participation, confirming its sustained crucial role in society as a collective form of human flourishing.

Acknowledgments

This article contains ethnographic material included in my text submitted to the 2019 Andrew Goodwin Memorial Essay Prize. I am thankful to the Andrew Goodwin Memorial Trust for their recognition and economic support. Many thanks to Byron Dueck, Laura Denyer-Willis and the editors and reviewers of Popular Music for their comments on earlier versions of this article. I also want to acknowledge all the research participants quoted here as co-creators of these insights. The doctoral fieldwork was funded by a scholarship from London South Bank University.