Article contents

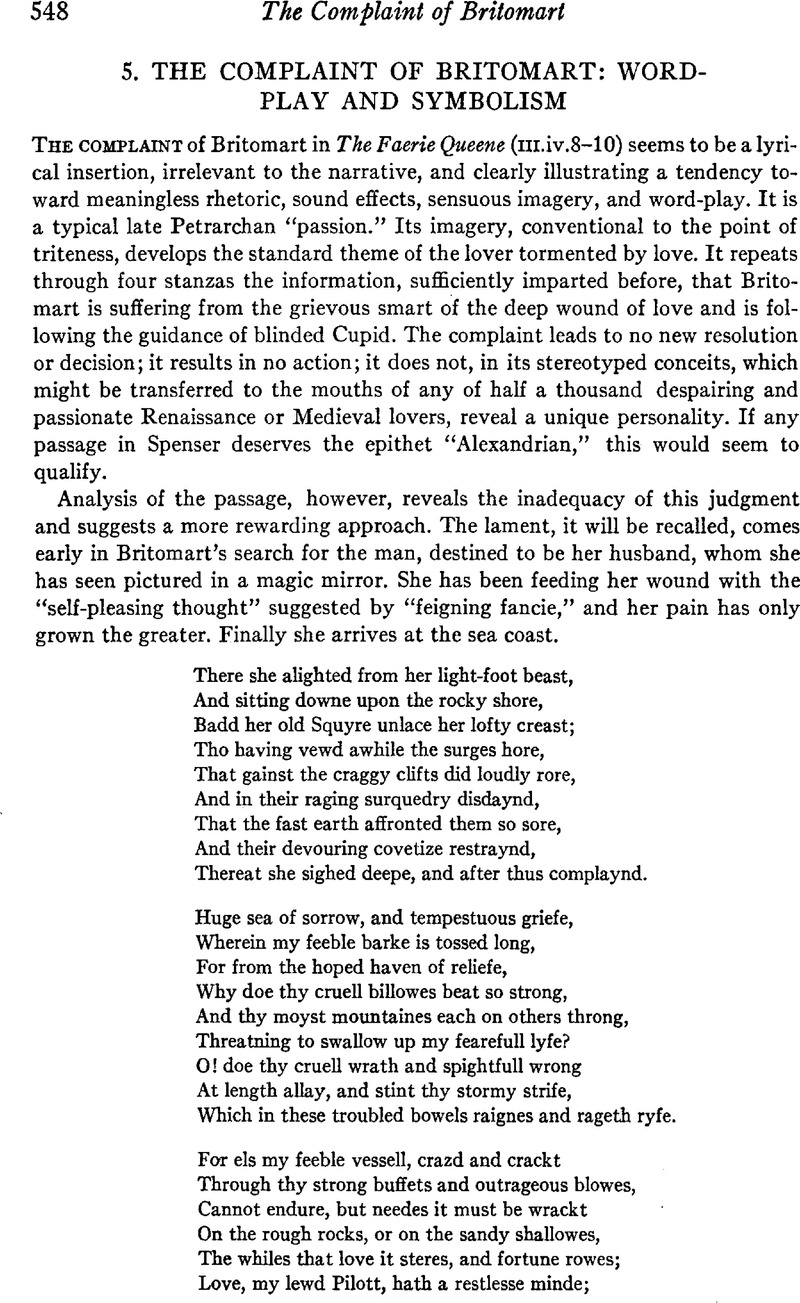

The Complaint of Britomart: Word-Play and Symbolism

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 December 2020

Abstract

- Type

- Comment and Criticism

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Modern Language Association of America, 1951

References

Note 1 in page 549 It is so named by Alexander Gill in his Logonomia Anglica, ed. O. J. Jiriczek in Quellen und Forschungen, xc, 104–105.

Note 2 in page 549 Probably the most famous literary treatment of the conceit is that of Petrarch in his sonnet beginning “Passa la naue” (No. clxxxix in the modern numbering). Among the popular and influential Renaissance commentators, both Squarciafico and Vellutello stress the moral as well as the erotic implications of the poem. Thus in Squarciafico's interpretation the poet despairs lest he be unable to return to the path of virtue, and in Vellutello's, lest he fail to reach the porto di salute, salvation.

An even more influential use of the conceit as a moral and religious metaphor is that of Psalm era (Vulgate cvi), especially as interpreted by Augustine (P.L. xxxvii. 1425–26). Augustine gives the traditional Christian meaning of the conceit.

The extent to which the conceit was used in a moral and religious sense may be indicated by the following scattered sources, in which the interpretation is explicit: the pseudo-Augustinian Soliloquies, Ch. 35, P.L. XL.894–895; Petrarch, Secrelum in Opera (Basel, 1581), i, 351; Geoffrey Whitney, A Choice of Emblems (London, 1586), sig. S1; John Davies of Hereford, Microcosmus in Works, ed. A. B. Grosart (Chertsey Worthies' Library, n.p., 1879), ii, 38; Christopher Sutton, Discs Mori, ed. J. E. Tyler (London, 1840), p. 33; Francis Quarles, Emblems (London, 1635), Lib. ii.ll. Many more could be added. Spenser himself, of course, uses the image elsewhere in the same way, most notably in Guyon's journey in the last canto of Book ii.

Note 3 in page 550 That the man who is guided by reason is free from, or unaffected by, the vicissitudes of Fortune, is of course traditional Medieval and Renaissance teaching. See, e.g., Boethius, De Consolatione Philosophiae; Petrarch, De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae; Justus Lipsius, De Constantin; Hamlet iii.ii.73–82.

Note 4 in page 550 Mythologiae, sine Explicationis Fabularum (Frankfurt, 1596), p. 871.

Note 6 in page 550 Confessiones, Lib. xiii, cap. 17, P.L. xxxii.853; cf. Isidore, Mysticorum Expositiones Sacramentorum in P.L. LXXXIII.210; Thomas Wright, The Passions of the Mind in General (London, 1604), p. 319.

Note 8 in page 550 On this point I am in agreement with A. S. P. Woodhouse, “Nature and Grace in The Faerie Qaeene,” ELH, xvi (1949), 201–228.

Note 7 in page 550 Cf. Strigelius's comment on Ps. cvii.32: “Exaltent eum in Ecclesia plebis, id est, non modo priuatim inter suos, sed etiam publiée apud alios profiteatur a quo adiuti sint, videlicet non a Neptuno aut a Christophoro, sed a vëro & uiuo Deo.” (“firoiivwiaTa in Omnes Psalmos Dauidis [Lipsiae, 1563], p. 500.) Natalis Comes, whose discussion of Neptune is typical, associates Neptune with the treachery and passion of his own seas, concluding ”huic Deo taurus niger merito immolabatur, quod tauri & furorem & mugitum imitaretur Neptunus“ (op. cit., p. 173). At the same time, however, the vow paid to Neptune is an act of pagan virtue: ”at calamitates, quas pro neglecto Neptuno passus est, quid aliud significant quam Dei cultum sine calamitate non negligi?“ (op. cit., p. 175). Landino's interpretation of Neptune as the higher reason, or reason illuminated by grace (contrasting with the lower reason, Aeolus) in Aeneid 1.50–156, is tempting. Here it would emphasize Britomart's feeling that the lower reason itself is not sufficient. It is not, however, common in the Renaissance. See Vergil, Aeneid, ed. Montfortius et al. (Basel, 1596), p. 3019. Neptune is similarly glossed by Ridewall as Inlelligentia, Hans Leibschiitz, Fidgentius Metaforalis (Leipzig, 1926), p. 93.

Note 8 in page 550 A similar play on the word is made in iii.ix.28.3.

- 2

- Cited by