Article contents

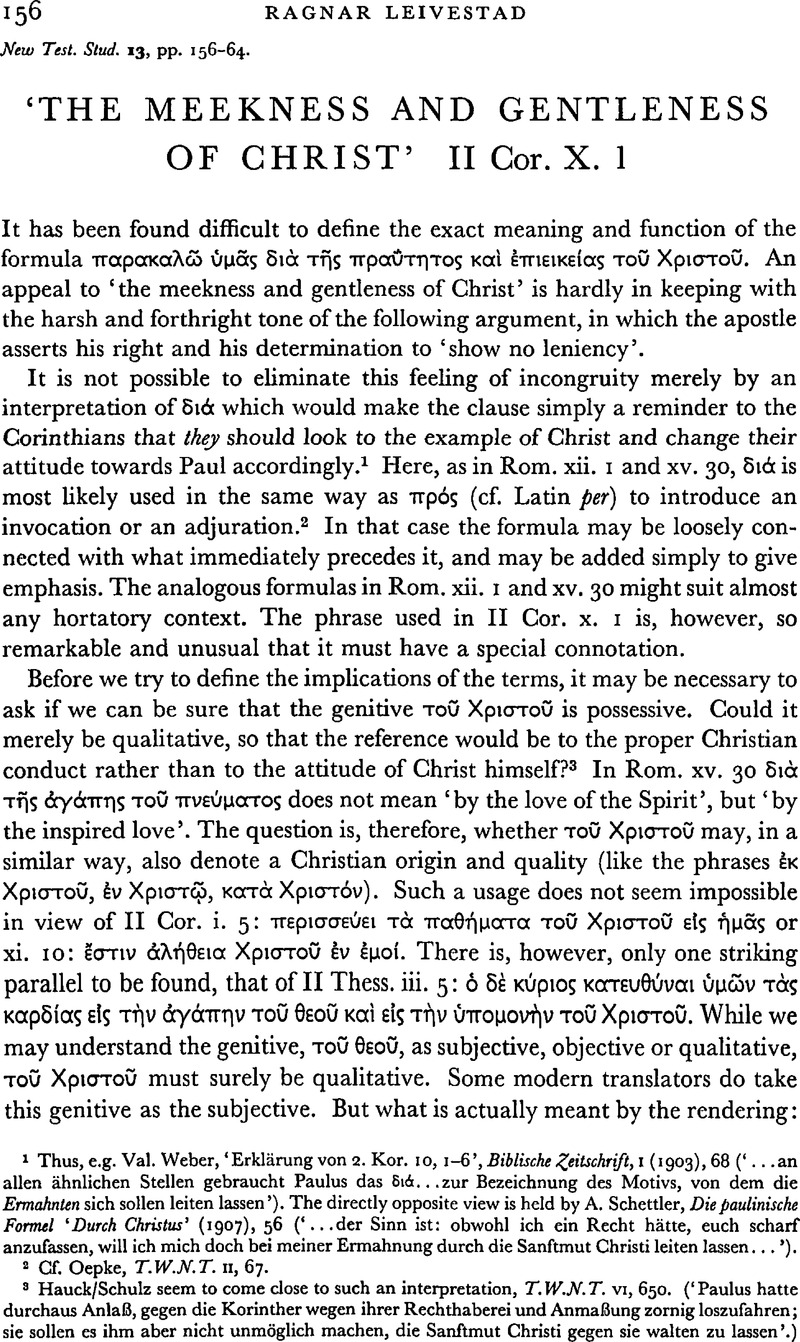

‘The Meekness and Gentleness of Christ’ II Cor. x. 1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1966

References

page 156 note 1 Thus, e.g. Weber, Val., ‘Erklärung von 2. Kor. 10, 1–6’, Biblische Zeitschrift, I (1903), 68Google Scholar (‘…an alien ähnlichen Stellen gebraucht Paulus das δι⋯…zur Bezeichnung des Motivs, von dem die Ermahnten sich sollen leiten lassen’). The directly opposite view is held by Schettler, A., Die paulinische Formel ‘Durch Christus’ (1907), 56Google Scholar (‘…der Sinn ist: obwohl ich ein Recht hätte, euch scharf anzufassen, will ich mich doch bei meiner Ermahnung durch die Sanftmut Christi leiten lassen…’).

page 156 note 2 Cf. Oepke, , T.W.N.T. II, 67.Google Scholar

page 156 note 3 Hauck/Schulz seem to come close to such an interpretation, T.W.N.T. VI, 650.Google Scholar (‘Paulus hatte durchaus Anlaβ, gegen die Korinther wegen ihrer Rechthaberei und Anmaβung zornig loszufahren; sie sollen es ihm aber nicht unmöglich machen, die Sanftmut Christi gegen sie walten zu lassen’.)

page 157 note 1 Lietzmanns, Handbuch z. N.T. III, 2Google Scholarad loc. (‘Es ist also nicht auf die von Jesus in seinem Erdenleben bewährte Geduld hingewiesen, sondern die Geduld gemeint, die in den Christen wohnen muβ, weil Christus in ihnen wohnt’).

page 158 note 1 ‘Sanftmut, Huld and Demut in der alten Kirche’, Festgabe für J. Kaflan (1920), 116.Google Scholar

page 158 note 2 T.W.N.T. II, 585.Google Scholar

page 158 note 3 Cf. Spicq, C., ‘Bénignité, mansuétude, douceur, clémence’, Revue Biblique (1947), 336Google Scholar: ‘I1 s'agit ici de résignation, de douceur patiente, très proche de la πραūτης.’—But he has not been able to free himself from the influence of his forerunners, so he, too, attempts in some way to find room for the idea of a quality peculiar to a superior: ‘Le fils de Dieu qui domine la souffrance est πραūς. La clémence est toujours une vertu souveraine qui suppose, chez le sujet qui la possède, une grandeur morale, sinon politique.’

page 158 note 4 T.W.N.T. II, 586.Google Scholar His exegesis of Phil. iv. 5 (ibid.) is equally far-fetched. (‘Mildness’, ‘gentleness’ (Knox: ‘courtesy’) are proper renderings.) C. Spicq gives a much better account of the real import of the term in the N.T.: ‘Dans le Nouveau Testament, l'έπıείκεıα est toujours une vertu propre aux supérieurs ou aux hommes proches de Dieu, mais son assimilation à la ![]() est de plus en plus nette, et elle signifie le plus souvent une douce et humble patience’ ( op. cit. p. 336). His first sentence is wrong, however. There is no logical connexion between superiority and nearness to God. He is only making concessions to an exegetical tradition, which I hope to undermine. I have noticed some similar concessions in the New English Bible.

est de plus en plus nette, et elle signifie le plus souvent une douce et humble patience’ ( op. cit. p. 336). His first sentence is wrong, however. There is no logical connexion between superiority and nearness to God. He is only making concessions to an exegetical tradition, which I hope to undermine. I have noticed some similar concessions in the New English Bible.

page 160 note 1 Admitted by Harnack, von (op. cit. p. 116)Google Scholar and Lietzmanns, (T.W.N.T. II, 587).Google Scholar They hold this use of έπıεıκής to be exceptional in the Bible, though in accordance with profane and later Christian usage.

page 161 note 1 T.W.N.T. IV, 649.Google Scholar Commenting on Matt. xi. 29.

page 161 note 2 Cf. Or. Sib. VIII, 256Google Scholar: ![]()

![]()

page 161 note 3 Von Harnack's opinion, that ταπεıνός has a positive and θαρρ⋯ a negative connotation, is impoible ( op. cit. pp. 113 f. n. 3). θαρρ⋯ is always used in a positive sense: ‘to be confident’, ‘to be brave’ (cf. II Cor. v. 6, 8; vii. 16). In an article in Novum Testamentum I intend to demonstrate that ταπεıνός is very seldom used to express a virtue and never has the meaning ‘humble’ in Paul's letters.

page 162 note 1 It seems to me much more likely that educated members of the Greek congregations might despise his rhetorical gifts and take offence at his unphilosophical argument than that anybody would scoff at his lack of the gift of ecstatic preaching.

page 163 note 1 As we probably have to accept the difficult reading ![]() (in spite of B) it seems impossible to understand the future tense eschatologically (cf. iv. 10ff.; Rom. viii. 17). The analogy has not been carried through. This is not surprising. There is in the life of a Christian a real anticipation of the eschatological consummation. He is already raised with Christ and alive to God in him (Rom. vi. 4, II; Gal. ii. 20; II Cor. v. 17), and the power of his resurrection is experienced even here and now (Phil. iii. 10). The implication of the future tense (

(in spite of B) it seems impossible to understand the future tense eschatologically (cf. iv. 10ff.; Rom. viii. 17). The analogy has not been carried through. This is not surprising. There is in the life of a Christian a real anticipation of the eschatological consummation. He is already raised with Christ and alive to God in him (Rom. vi. 4, II; Gal. ii. 20; II Cor. v. 17), and the power of his resurrection is experienced even here and now (Phil. iii. 10). The implication of the future tense (![]() ) must then be that Paul is thinking of his next visit in Corinth and the proof he will give the Corinthians that Christ is really speaking through him. There is a latent threat in his words: just as they have forced him to boast, although it was foolish, so they may force him to be ‘brave’ and demonstrate authority and power in a manner which is not in accordance with his principles and God's true intentions (cf. x. 2; xiii. 10). But he shrinks back from this threat himself, praying that he may rather continue to be ⋯σθενής (xiii. 7ff.).

) must then be that Paul is thinking of his next visit in Corinth and the proof he will give the Corinthians that Christ is really speaking through him. There is a latent threat in his words: just as they have forced him to boast, although it was foolish, so they may force him to be ‘brave’ and demonstrate authority and power in a manner which is not in accordance with his principles and God's true intentions (cf. x. 2; xiii. 10). But he shrinks back from this threat himself, praying that he may rather continue to be ⋯σθενής (xiii. 7ff.).

- 3

- Cited by