Article contents

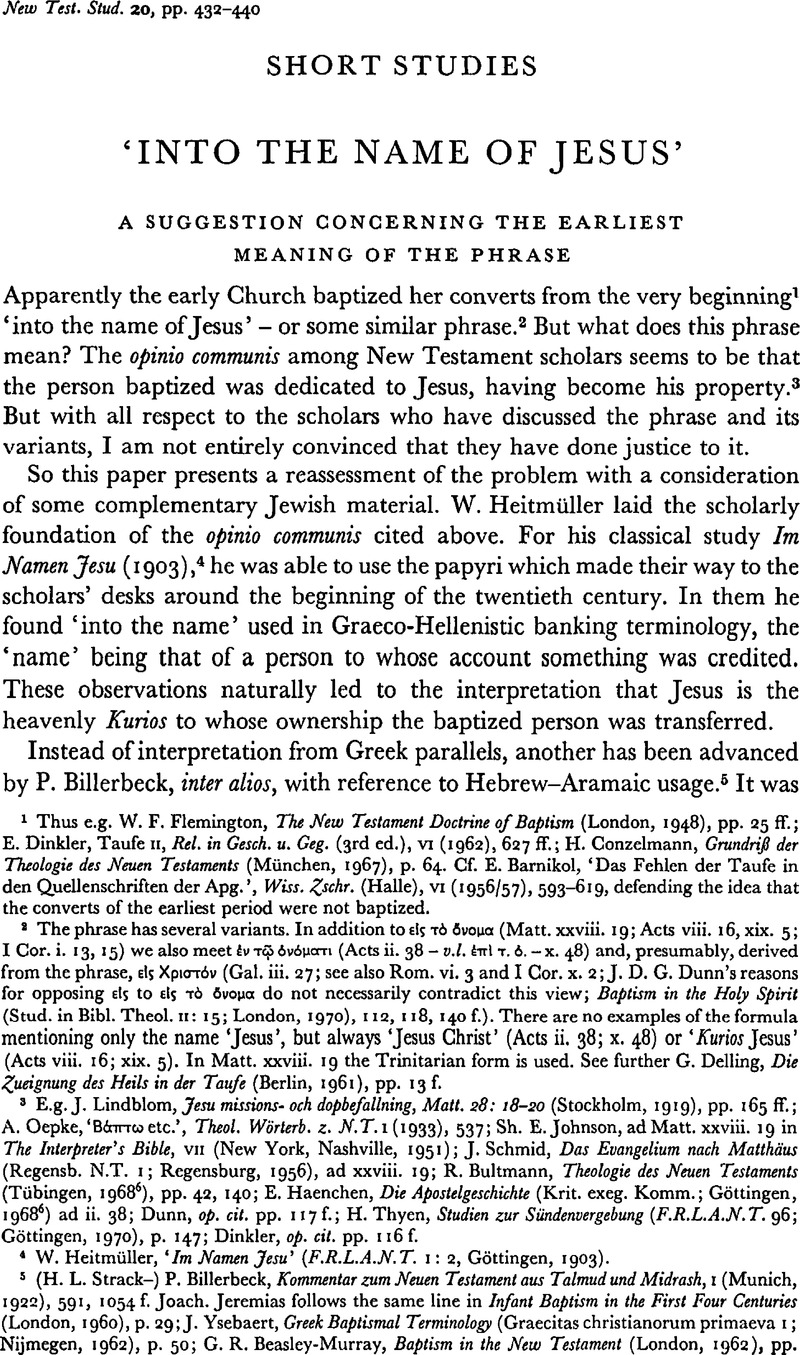

‘Into the Name of Jesus’

A Suggestion Concerning the Earliest Meaning of the Phrase

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Short Studies

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1974

References

page 432 note 1 Thus e.g. Flemington, W. F., The New Testament Doctrine of Baptism (London, 1948), pp. 25 ff.Google Scholar; Dinkler, E., Taufe II, Rel. in Gesch. u. Geg. (3rd ed.), VI (1962), 627 ff.Google Scholar; Conzelmann, H., Grundriβ der Theologie des Neuen Testaments (München, 1967), p. 64Google Scholar. cf. Barnikol, E., ‘Das Fehlen der Taufe in den Quellenschriften der Apg.’, Wiss. Zschr. (Halle), VI (1956/1957), 593–619Google Scholar, defending the idea that the converts of the earliest period were not baptized.

page 432 note 2 The phrase has several variants. In addition to είς τό őνομα (Matt. xxviii. 19; Acts viii. 16, xix. 5; I Cor. i. 13, 15) we also meet έν τω̣͊ όνόματι (Acts ii. 38 – v.l. έπί τ. ό. – x. 48) and, presumably, derived from the phrase, είς Χριστόν (Gal. iii. 27; see also Rom. vi. 3 and I Cor. x. 2; J. D. G. Dunn's reasons for opposing είς to είς τό őνομα do not necessarily contradict this view; Baptism in the Holy Spirit (Stud. in Bibl. Theol. 11: 15; London, 1970), 112, 118, 140 f.Google Scholar). There are no examples of the formula mentioning only the name ‘Jesus’, but always ‘Jesus Christ’ (Acts ii. 38; x. 48) or ‘Kurios Jesus’ (Acts viii. 16; xix. 5). In Matt. xxviii. 19 the Trinitarian form is used. See further Delling, G., Die Zueignung des Heils in der Taufe (Berlin, 1961), pp. 13 f.Google Scholar

page 432 note 3 E.g. Lindblom, J., Jesu missions- och dopbefallning, Matt. 28: 18–20 (Stockholm, 1919), pp. 165 ff.Google Scholar; Oepke, A., ‘Βάпτω etc.’, Theol. Wörterb. z. N.T. I (1933), 537Google Scholar; Sh. E. Johnson, ad Matt. xxviii. 19 in The Interpreter's Bible, VII (New York, Nashville, 1951)Google Scholar; Schmid, J., Das Evangelium nach Matthäus (Regensb. N.T. I; Regensburg, 1956)Google Scholar, ad xxviii. 19; Bultmann, R., Theologie des Neuen Testaments (Tübingen, 1968 6), pp. 42, 140Google Scholar; Haenchen, E., Die Apostelgeschichte (Krit. exeg. Komm.; Göttingen, 1968Google Scholar6) ad ii. 38; Dunn, op. cit. pp. 117 f.; Thyen, H., Studien zur Sündenvergebung (F.R.L.A.N.T. 96; Göttingen, 1970), p. 147Google Scholar; Dinkler, op. cit. pp. 116 f.

page 432 note 4 Heitmüller, W., ‘Im Namen Jesu’ (F.R.L.A.N.T. 1: 2, Göttingen, 1903).Google Scholar

page 432 note 5 (Strack, H. L.–) Billerbeck, P., Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud und Midrash, I (Munich, 1922), 591, 1054 fGoogle Scholar. Joach. Jeremias follows the same line in Infant Baptism in the First Four Centuries (London, 1960), p. 29Google Scholar; Ysebaert, J., Greek Baptismal Terminology (Graecitas christianorum primaeva I; Nijmegen, 1962), p. 50Google Scholar; Beasley-Murray, G. R., Baptism in the New Testament (London, 1962), pp. 90 f.Google Scholar; Kretschmar, G., ‘Die Geschichte des Taufgottesdienstes in der alten Kirche’, in Leiturgia (ed. Müller, K. F. and others; Kassel–Wilhelmshöhe, 1970), pp. 18, 32 f.Google Scholar This interpretation was first suggested by Brandt, A. J. H. W., ‘Onoma en de Doopsformule in het Nieuwe Testament’, Theol. Tijdschr. xxv (1891), 565–610Google Scholar, and by Dalman, G., Die Worte Jesu, I (Leipzig, 1898), 250 f.Google Scholar

page 433 note 1 See Billerbeck, , Kommentar, I, 1005Google Scholar, and Bietenhard, H., Onoma etc., Theol. Wörterb. z. N.T. v (1954), 275Google Scholar. Typically enough, Kuss, O. says (‘Zur vorpaulinischen Tauflehre im Neuen Testament’, originally published in 1951, now reprinted in Auslegung und Verkündigung, I, Regensburg, 1963, 98Google Scholar): ‘Es ist nicht von entscheidender Bedeutung ob man die Formel eis to onoma aus dem griechischen (…) oder aus dem semitischen (…) Sprachgebrauch ableitet.’

page 433 note 2 Delling, Die zueignung des Heils in der Taufe

page 433 note 3 Delling, op. cit. p. 43.

page 433 note 4 See e.g. Bietenhard, op. cit. p. 275, and Delling, op. cit. pp. 32 ff.

page 434 note 1 Cf. e.g. Ullmann, S., Semantics (Oxford, 1962), pp. 64 ff.Google Scholar

page 434 note 2 Billerbeck, op. cit. p. 1055.

page 435 note 1 cf.Leipoldt, J., Die urchristliche Taufe im Lichte der Religionsgeschichte (Leipzig, 1928), p. 34Google Scholar; Delling, op. cit. p. 39.

page 435 note 2 Bietenhard, loc. cit.

page 435 note 3 Cf. Delling, op. cit. p. 37.

page 435 note 4 Cf. Delling, op. cit. p. 43. So also Heitmüller, op. cit. pp. 124 f.

page 435 note 5 This translation phenomenom explains why prepositional phrases with όνομα are so numerous in the LXX, although in many cases they must have sounded coarse or difficult to any sensitive Greek ear. (See e.g. Bietenhard, op. cit. p. 262; Delling, op. cit. pp. 27 ff.) Nevertheless, as is often the case with cultic or religious language, the group using the holy text obviously adopted its wordings and became accustomed to them. Expressions that might otherwise have seemed odd found a natural place within a kind of technical language, which may or may not have coloured the usage in other areas of life. (Cf. on this problem Gehman, H. S., ‘The Hebraic Character of Septuagint Greek’, Vet. Test. I (1951), 90Google Scholar, and Ch. Rabin, , ‘The Translation Process and the Character of the Septuagint’, Textus VI (1968), 1–26.Google Scholar) Thus, when dealing with NT όνομα phrases it is not feasible to derive them directly from the Hebrew OT and from later Semitic usage in first-century Palestine and regard the NT phrases only as direct translations from a Semitic substrate. In addition it seems necessary to take into account the possibility that this translation was promoted by the religious language, including the όνομα terms, of the Greek-speaking Jewish communities. To assume, however, that our phrase is inspired solely and directly by a Hellenistic–Jewish usage does not seem to be a viable solution, as the examples of the phrase introduced by εις are very rare. (See Delling, op. cit. p. 27.)

page 435 note 6 Cf. E.g. Bultmann, Theologie, 40, who assumes that the phrase orginated in the Hellenistic community

page 435 note 7 This does not suggest a theory of a closed Palestine Jewry or Christianity isolated from the Hellenistic world, as if they did not themselves form part of the that world. See lately Sevenster, J. N., Do you know Greek? (Suppl. Nov. Test. 19; Leiden, 1968)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Hengel, M., Judentum und Hellenismus (Wiss. Unters, z. N.T. 10; Tübingen, 1969)Google Scholar. Bietenhard does not discuss this possibility of a variety and development of meanings (op. cit. p. 275). Cf., on the other hand, the more diversified discussion of Heitmüller, op. cit. pp. 115 ff.

page 435 note 8 Delling speaks of a ‘prepositional’ usage of leshem in cases such as the ones cited above, where for example a lamb is offered ‘as (leshem) a Passover lamb’. He admits only as a theoretical possibility that such a ‘prepositional’ leshem was literally translated into Greek, then kept without being understood and finally re-interpreted. This is not the place for a discussion of possible re-interpretations. It is, however, hard to see how a theory of literal translation could be contradicted by a contention that Paul has related εις τό όνομα to the name of Jesus and has not understood it as a ‘preposition’ (op. cit. p. 41). This is hardly proved by I Cor. i. 13 ff. (op. cit. p. 68), especially as Delling reads this passage on the assumption that Paul consciously distinguished between usages of εις τό őνομα. Are not questions of linguistic usage of a more complex nature and should we not guard against distinctions that depend so much on our own translations? It may prove useful in this context to quote b. Zeb. 30 a. In this passage cultic intentions are discussed and leshem is used as a ‘preposition’ (according to Delling's distinction). But the same text gives the following rule: ‘it is impossible to pronounce two intentions ![]() lit. ‘two names’) simultaneously’. There is no hint of a distinction between alleged ‘prepositional’ and ‘substantial’ usages, and it seems that the passage invalidates Delling's argument based on I Cor. i.

lit. ‘two names’) simultaneously’. There is no hint of a distinction between alleged ‘prepositional’ and ‘substantial’ usages, and it seems that the passage invalidates Delling's argument based on I Cor. i.

In addition we may take into consideration M. Ab. Z. iii. 7, with its Gemara in b. Ab. Z. 48 a. The Mishnah discusses the Asherahs and assumes a case in which ‘somebody lopped and trimmed (a tree) for idolatry ![]() . When the Gemara refers to this clause, however, it replaces leshem with a simple l5. (This is the case in the manuscripts followed by Bomberg-Goldschmidt; the Munich MS, however, reads leshem.) Nor in this case do we seem justified in assuming a ‘prepositional’ usage as consciously delimited from a ‘substantial’ one. Is the passage, perhaps, parallel to the Pauline εις τò όν7ogr;μα vs. εις?

. When the Gemara refers to this clause, however, it replaces leshem with a simple l5. (This is the case in the manuscripts followed by Bomberg-Goldschmidt; the Munich MS, however, reads leshem.) Nor in this case do we seem justified in assuming a ‘prepositional’ usage as consciously delimited from a ‘substantial’ one. Is the passage, perhaps, parallel to the Pauline εις τò όν7ogr;μα vs. εις?

page 436 note 1 See also, e.g., M. Hul. ii. 10 (as a burnt-offering); b. Pes. 38 b (loaves saved as a Massah), b. Shab. 50 a (branches brought together to be firewood). Here we may also quote b. Yeb. 45 b, ‘somebody buys a slave from a Gentile and he comes to him and receives the proselyte baptism to be a freeman ![]() and M. Ned. iv. 8 (somebody gives (food) to another as a gift).

and M. Ned. iv. 8 (somebody gives (food) to another as a gift).

page 436 note 2 See also, e.g., M. Pes. v. 2 (the Passover-sacrifice slaughtered as such, in its named purpose).

page 438 note 1 With a suffix in M. Git. iii. 2 (a letter of divorce, written for her; similarly T. Git. ii. 7).

page 439 note 1 Cf. Jeremias, , Infant Baptism, p. 29.Google Scholar

page 439 note 2 Cf. e.g. Bultmann, , Theologie, pp. 42, 139 f.Google Scholar; Dinkler, , RGG VI 3, 629Google Scholar; Thyen, , Sündenvergebung, 148Google Scholar. See also Ep.Barn. 16, 17 f.

page 439 note 3 Longenecker, R. N., ‘Some Distinctive Early Christological Motifs’, N.T.S. XIV (1967/1968), 533 ff.Google Scholar

page 439 note 4 Cf. Delling, Zueignug des Heils.

page 439 note 5 Thus, e.g., Thyen, op. cit. p. 148; Conzelmann, H., Geschichte des Urchristentums (Grundriße zum N.T., N.T.D. Ergänz, 5; Göttingen, 1969), p. 36Google Scholar; Frhr, H. von Campenhausen vigorously denies that the name of Jesus was mentioned at baptism (‘Taufen auf den Namen Jesu?’, Vig. Christ. XXV (1971), 1–16).Google Scholar

page 439 note 6 See Jas. ii. 7; Herm. Sim. viii. 6, 4; Just. Apol. 61, 11. Cf. Bultmann, , Theologie, pp. 136 f.Google Scholar

page 440 note 1 Cf. also passages such as M. Zeb. ii. 4 and M. Men. i. 3, where cases are discussed in which the person making the sacrifice and the priest, respectively, perform the rite in silence, i.e. thus raising the question of his intention in relation to what he is actually doing.

page 440 note 2 Cf. also Thyen, op. cit. pp. 148 f.

page 440 note 3 See, e.g., Cullmann, O., Baptism in the New Testament (Stud. in Bibl. Theol. I; London, 1950), pp. 9 ff.Google Scholar; Schweizer, E., Church Order in the New Testament (Stud. in Bibl. Theol. 32; London, 1961), p. 41Google Scholar; Dinkler, , RGG VI 3, 628Google Scholar, Thyen, op. cit. pp. 145 ff.; Conzelmann, Geschichte, p. 35. For other opinions, see e.g. Dahl, N. A., ‘The Origin of Baptism’, Norsk Teol. Tidsskr. LXI (1955), 36–52Google Scholar; Jeremias, , Infant Baptism, p. 24Google Scholar; Kraft, H., ‘Die Anfänge der christlichen Taufe’, Theol. Zschr. XVII (1961), 399–412.Google Scholar

- 6

- Cited by