What shapes protest behavior in postwar societies? Protest activity is a ubiquitous feature of contemporary politics (Ortiz et al. Reference Ortiz, Burke, Berrada and Cortés2013), with important implications for governance and policy (Dalton, Sickle, and Weldon Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2009). Most research on political protest, however, has been conducted in stable and peaceful societies (Bernhagen and Marsh Reference Bernhagen and Marsh2007; Dalton, Sickle, and Weldon Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2009; Quaranta Reference Quaranta2016; Norris, Walgrave, and Aelst Reference Schussman and Soule2005; Rüdig and Karyotis Reference Rüdig and Karyotis2014; Snow and Soule Reference Snow and Soule2010; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998). We know far less about the drivers of protest in countries emerging from armed conflict. To fill this gap, we investigate variation in protest events and individual participation in protests in postwar Kosovo. The main goal of the article is to improve our understanding of protest behavior in postwar societies by systematically analyzing the type of grievances or demands that are more likely to generate protest mobilization and the factors that shape individual protest participation in such contexts.

With few notable exceptions (Freitag, Kijewski, and Oppold Reference Freitag, Kijewski and Oppold2019; Kelmendi Reference Kelmendi and Agani2012; Mahr Reference Mahr2018), the literature on postconflict countries has generally neglected protest behavior. Much of this literature, however, argues that political attitudes and behavior in countries affected by conflict are qualitatively different (Kelmendi and Rizkallah Reference Kelmendi and Rizkallah2018; Colletta and Cullen Reference Colletta and Cullen2000; Kijewski and Freitag Reference Kijewski and Freitag2018). Some authors argue that political agency in postconflict contexts is “apathetic” due to excessive international intervention, with international actors empowering national elites while disempowering grassroots movements (Autesserre Reference Autesserre2014; Pouligny Reference Pouligny2006; McMahon Reference McMahon2017; Orjuela Reference Orjuela2003; Belloni Reference Belloni2001). Others, however, find that while internationally sponsored NGOs are weak and unable to mobilize civic activism, antiestablishment movements that mobilize citizens for contentious political action can and do emerge in postwar contexts (Kelmendi Reference Kelmendi and Agani2012). In particular, these studies observe that as external actors engage in peace and state-building efforts, local ethnic groups resist new institutions via boycotts and protests (Keranen Reference Keranen2013), especially if they are perceived as violating sovereignty claims of self-rule (Mahr Reference Mahr2018; Kelmendi Reference Kelmendi and Agani2012; Radin Reference Radin2020). At the individual level, moreover, some studies have found that exposure to wartime violence leads to increased political participation (Bellows and Miguel Reference Bellows and Miguel2009; Blattman Reference Blattman2009), including in Kosovo (Freitag, Kijewski, and Oppold Reference Freitag, Kijewski and Oppold2019).

The academic literature on protest behavior in postwar societies is thus still at an early stage, and there are a number of gaps to be filled. Many of the works cited above focus on postwar civic and political participation. Yet studies from other contexts suggest that protest behavior has its own distinct logic and causes that may differ from other forms of engagement, particularly institutionalized civic engagement (Bernhagen and Marsh Reference Bernhagen and Marsh2007; Chenoweth and Stephan Reference Chenoweth and Stephan2011; Freitag, Kijewski, and Oppold Reference Freitag, Kijewski and Oppold2019). Moreover, studies focusing specifically on protest activity in postwar societies generally attempt to explain a discrete protest event or a series of contentious events, such as protests occurring against international actors engaged in peacebuilding. To our knowledge, there are no studies that systematically analyze protest events to explain general protest behavior in postwar societies.

To address these gaps, we offer and test a novel theory of protest behavior in postwar societies. Our theory builds on the assumption that certain categories of grievances, such as ethnic grievances, are more likely to generate responses of protest because they are deeply felt and widely shared (Simmons Reference Simmons2014). At the societal level, we hypothesize that perceived grievances about ethnic group security and ethnic group status are more likely to generate protest mobilization than other categories of grievances, such as, for example, economic grievances. At the individual level, our theory expects that individuals who perceive that their ethnic group is discriminated are more likely to protest than those who do not.

To evaluate our theory, we use a two-pronged empirical strategy. First, we employ protest event analysis (Koopmans and Rucht Reference Koopmans and Rucht2002) using an original dataset of protest events, the Kosovo Protest Data (KPD). Among others, KPD data allows us to investigate intertemporal and cross-ethnic variation in protest activity, including protest frequency, size, and grievances. Second, we employ European Social Survey (ESS) data to investigate individual-level variation using logit models to predict protest participation in Kosovo. We focus our analysis on postwar Kosovo. Prior to the 1998–1999 war, Kosovo Albanians responded to state violence with nonviolent resistance, including protests and strikes (Hetemi Reference Hetemi2020; Pula Reference Pula2004; Petersen Reference Petersen2011). After the war, Kosovo was administered by the UN Peacekeeping Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) until 2008 when it declared independence, and during this time it was the site of a multitude of protests. The availability of a comprehensive archive of media reports enabled us to construct a new dataset of protest events in postwar Kosovo, which provides insights that can be tested in other postconflict settings.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows. We begin by reviewing existing theories of protest activities. Then we discuss our theory’s assumptions and hypotheses. Subsequently, we examine historical protest repertoires in Kosovo. We then discuss patterns of protest events in Kosovo relying on our original dataset. Finally, we investigate the determinants of variation in individual protest participation using survey data from Kosovo. We conclude with a discussion of the limitations of our study and suggestions for future research.

Existing Theories of Protest Activity

Theories of protest and social movement activity in peaceful societies offer different avenues for understanding the emergence of, and participation in, political protest. Microlevel approaches focus on individual-level determinants of protest participation and highlight distinct theoretical rationales for individual protest behavior. This literature is large and diverse but can be grouped in five different schools of thought (Machado, Scartascini, and Tommasi Reference Machado, Scartascini and Tommasi2011; Rüdig and Karyotis Reference Rüdig and Karyotis2014).

The first, and arguably oldest perspective, emphasizes grievances. This perspective underscores issues of perceived injustice, inequality, and unfair treatment as key generators of protest activism (Gurr Reference Gurr1970). Recent comparative analyses of political protest in Europe, for example, find that political protest increases during times of economic crises (Quaranta Reference Quaranta2016) and that variables such as personal financial situation, blame attribution, and perceptions of fairness are associated with protest participation (Rüdig and Karyotis Reference Rüdig and Karyotis2014). The second perspective emphasizes political disaffection and alienation (Norris, Walgrave, and Aelst Reference Norris, Walgrave and Van Aelst2005, 189). According to this perspective, beliefs in the responsiveness of the political system, such as dissatisfaction with democracy, or lack of trust in the workings of or respect for political institutions, drive protest potential (Machado, Scartascini, and Tommasi Reference Machado, Scartascini and Tommasi2011; Moseley Reference Moseley2015).

The third perspective emphasizes individual resources (Dalton, Sickle, and Weldon Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2009; Schussman and Soule Reference Schussman and Soule2005). It highlights sociodemographic characteristics such as age, education, occupation, and income as important drivers of participation in protests positing, for example, that the rich and the more educated are more likely to engage politically, including by protesting. A fourth perspective focuses on social links, or networks, that serve as resources to increase opportunities for people to engage in participation (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). If individuals are embedded in social networks—such as political parties, trade unions, civil society organizations—that encourage them to participate, then they are more likely to engage in protests. Finally, the fifth perspective emphasizes political motivational attitudes. According to this approach, factors such as interest in politics (Bernhagen and Marsh Reference Bernhagen and Marsh2007) or interpersonal trust (Benson and Rochon Reference Benson and Rochon2004) affect an individual’s propensity to protest (Norris, Walgrave, and Aelst Reference Norris, Walgrave and Van Aelst2005, 202).

At the macrolevel, prior research emphasizes three broad contextual features that shape the aggregate level of protest in a society (Dalton, Sickle, and Weldon Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2009, 53). The first, and the oldest one, focuses on grievances as key generators of protest activism (Gurr Reference Gurr1970; Kim Reference Kim1996; Loveman Reference Loveman1998; Snow and Soule Reference Snow and Soule2010; Simmons Reference Simmons2014; Varshney Reference Varshney2003). Numerous comparative studies of protest movements find that protest is associated with popular dissatisfaction (Harris Reference Harris2002; Wilkes Reference Rima2004) and identity-based political inequality (Jazayeri Reference Jazayeri2016), and that certain categories of grievances are especially likely to generate protest activism (Simmons Reference Simmons2014). Although much of the work on contentious collective action has dismissed grievances as ubiquitous, and thus of inadequate explanatory power, recent scholarship has begun demonstrating the analytical leverage of systematically incorporating grievances in the study of social mobilization (Simmons Reference Simmons2014).

The second macrolevel approach emphasizes structures and resources that facilitate the mobilization of protests. Resource mobilization theorists note, in particular, the role of organizations and movement entrepreneurs in the process of protest mobilization (McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Rucht Reference Rucht, McAdam, McCarthy and Mayer1996). According to this perspective, “a highly skilled public and citizens freely engaging in voluntary associations create a resource environment that can support collective action” (Dalton, Sickle, and Weldon Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2009, 54). Networks of organizations such as political parties, labor unions, universities, and local and international NGOs provide activists and protesters with critical resources such as material support, information, and expertise for protest activity to be organized and sustained (Loveman Reference Loveman1998, 484).

The third prominent macrolevel framework is the political opportunity structure (POS) approach, which emphasizes how institutional structures and political processes shape levels of protest activity. According to Tarrow (Reference Tarrow1998) social movements and cycles of protest are activated when changes in the political opportunity structure—especially widening of access to power, shifts in ruling alignments, elite conflict, and availability of potential influential allies—provide incentives for collective action.

This overview of the existing theoretical literature on protests suggests that explanations of protest behavior in postwar societies should pay attention to both the individual-level and macrolevel factors. At the microlevel, the analysis of protest participation should pay attention to socioeconomic factors, individual motivations, attitudes toward political institutions, and social and institutional networks, among others. At the macrolevel, variation in protest activity may be shaped by popular dissatisfaction and perceptions of grievances, networks of organizations that provide the resources to facilitate mobilization, as well as dynamics in political opportunities that usually come in the shape of exogenous shocks or forces.

Grievances and Protest Behavior in Postwar Societies: A Theory

Our explanation of protest behavior in postwar societies is influenced by the grievance approach to protests. Our theory builds, specifically, on the approach espoused by Simmons (Reference Simmons2014), which argues that at any given time in certain communities, some categories of grievances are more likely to resonate than others and thus more likely to generate responses of protest. This approach emphasizes the role of “deeply felt shared grievances” (Snow and Soule Reference Snow and Soule2010, 23). These “mobilizing grievances,” according to Snow and Soule, “are shared among some number of actors… [and] are felt to be sufficiently serious to warrant not only collective complaint but also some kind of corrective, collective action” (24). We argue that in societies emerging from ethnic civil war, grievances related to perceived ethnic discrimination, particularly perceived threats to group security or grievances regarding group status, are especially likely to motivate collective action in postwar societies.

The literature on ethnic conflict and civil wars demonstrates how perceived ethnic grievances play an important role in shaping ethnic mobilization in civil war (Gurr Reference Gurr1993, Reference Gurr2000; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000; Petersen Reference Petersen2002, Reference Petersen2011; Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013; Cederman, Gleditsch, and Wucherpfennig Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Wucherpfennig2017; Siroky et al. Reference Siroky, Warner, Filip-Crawford, Berlin and Neuberg2020). This literature emphasizes grievances such as perceived threats to survival of group cultures or physical existence (Rothchild and Hartzell Reference Rothchild and Hartzell1999) and concerns about political exclusion, relative deprivation and group status, and the possibility of downward mobility (Petersen Reference Petersen2011; Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013; Siroky et al. Reference Siroky, Warner, Filip-Crawford, Berlin and Neuberg2020). We argue that perceived ethnic grievances such as threats to group security or concerns about the group’s power status also generate protest mobilization in postconflict societies, because of two interrelated sets of factors.

The first has to do with the role of the sociopsychological legacies of ethnic civil wars.Footnote 1 Civil wars are destructive and violent processes that result in significant death, displacement, and economic damage. They foster resentment among previously conflicting parties, “especially among those who have lost family members, close friends, or property” (Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013, 64). More broadly, past experiences of violence, or a group’s status reversal as a result of the war, generate deeply felt collective emotions, including fear, anger, and resentment (Petersen Reference Petersen2011). Recent empirical work demonstrates that civil war hardens in-group political identities (Balcells Reference Balcells2012), magnifies collective threat perception (Canetti et al. Reference Canetti, Elad-Strenger, Lavi, Guy and Bar-Tal2017), increases levels of ethnonationalism in society (Dyrstad Reference Dyrstad2012), and reinforces beliefs about collective victimhood (Halperin and Bar-Tal Reference Halperin and Bar-Tal2011). As a result of these processes, concerns about ethnic security and the group’s power status are especially likely to constitute a category of “deeply felt shared grievances” and thus particularly likely to resonate broadly in postconflict environments.

The second group of factors contributing to the salience of ethnic grievances in postconflict settings has to do with the challenges and contradictions of postwar governance (Paris and Sisk Reference Paris and Sisk2009). To begin with, cessation of armed conflict is not automatically followed by significant improvements to the rule of law (Haggard and Tiede Reference Haggard and Tiede2014). Such a context sustains concerns about security, which is usually defined in ethnic terms (Downes Reference Downes2004). Furthermore, power-sharing arrangements established after ethnic civil war tend to entrench ethnic cleavages and divisions (Bieber Reference Bieber2006) while seldom fully mitigating the lack of trust between ethnic groups or concerns about group security (Downes Reference Downes2004; Morgan-Jones, Stefanovic, and Loizides Reference Morgan-Jones, Stefanovic and Loizides2021). Persuasion and coercion by ethnic political elites constitutes an additional important factor (Belloni Reference Belloni2001; Orjuela Reference Orjuela2003). Ethnic political parties, often with roots in wartime organizations, appeal to ethnic grievances to mobilize the political support of coethnic voters (Kelmendi Reference Kelmendi2017; Radin Reference Radin2020). Biased writing and teaching of history in schools also plays a role, further perpetuating ethnonationalist narratives of in-group victimhood (Swimelar Reference Swimelar2013; Selenica Reference Selenica2018; Fort Reference Fort2018; Baliqi Reference Baliqi2018).

Although international peacekeeping and state-building missions lower the risk of armed conflict recurrence (Fortna Reference Fortna2008), their ability to reduce postwar ethnocentrism or eradicate group security concerns is uneven and gradual (Paris and Sisk Reference Paris and Sisk2009; Page and Whitt Reference Page and Whitt2020). Awareness that the presence of peacekeepers is temporary means that former parties to the conflict “worry about each other’s intentions and their future security” (Downes Reference Downes2004, 234). The empirical record further indicates that the effect of transitional justice measures on reconciliation, psychological healing, or rule of law is similarly mixed (Thoms, Ron, and Paris Reference Thoms, Ron and Paris2008; Milanovic Reference Milanovic2015). Cognitive biases, and the continued strength of ethnonationalist narratives, impede the efforts of international war crimes tribunals to dispel prevailing notions of in-group victimhood and out-group blame. Similarly, international efforts to engineer an interethnic civil society are largely unsuccessful (Belloni Reference Belloni2001; Orjuela Reference Orjuela2003). Indeed, as international organizations are engaged in peacebuilding, their actions may themselves cause perceived ethnic grievances that mobilize protests (Keranen Reference Keranen2013), especially if the institutions or policies they promote are perceived as endangering claims of self-rule (Mahr Reference Mahr2018; Kelmendi Reference Kelmendi and Agani2012; Kelmendi and Radin Reference Kelmendi and Radin2018).

The discussion above allows us to formulate the following hypothesis:

H1: After ethnic civil war, perceived ethnic grievances—particularly perceived threats to group security or power status—are more likely to generate protest mobilization than other categories of grievances.

Hypothesis 1 operates at a societal or country level. To test this hypothesis, we need to systematically identify and categorize the grievances around which political protests in postconflict societies emerge. Following Simmons, we understand the term grievances as “the practices, policies, or phenomena” that protest leaders and movement members “are working to change (or preserve)” (Reference Simmons2014, 515). More specifically, hypothesis 1 implies that, all other things equal, in postconflict societies we are more likely to observe protests that emerge around stated ethnic grievances such as threats to group security or concerns about the group’s power status than protests that emerge around other categories of grievances, such as economic grievances or demands for democratic or transparent governance.

By perceived threats to ethnic group security or power status we mean the presence of real or imagined threats that generate “fears for the survival of group cultures or physical existence or over the possibility of downward mobility” (Rothchild and Hartzell Reference Rothchild and Hartzell1999, 256). Such fears about subordination or survival stem not only from policies or actions that heighten the perceived possibility of current or future material and physical harm to members of the ethnic group but also from processes that may lead to political status reversal. As Petersen and Staniland note, “While status can be complex, status relations among ethnic groups can generally be tied to […] state policy or ethnic composition of state’s offices” (Reference Petersen, Staniland, Saideman and Zahar2008, 98). According to this definition, concerns about status relations among groups in postwar, multiethnic societies are primarily motivated by access to state power. These concerns, in other words, are generated by real or perceived political, not economic, inequalities (Petersen and Staniland Reference Petersen, Staniland, Saideman and Zahar2008).Footnote 2 Concerns about political inequality and exclusion from power can heighten an ethnic group’s sense of vulnerability and incite unease about future security (Rothchild and Hartzell Reference Rothchild and Hartzell1999, 257). Even power-sharing agreements may not ameliorate security concerns in postwar contexts, as “each side fears that the other will attempt to capture the state, exclude them from power and resources, and use the instruments of state power to repress them” (Downes Reference Downes2004, 233). These collective fears for the future are magnified by information problems, problems of credible commitment, and the security dilemma that affect multiethnic societies emerging from war (Lake and Rothchild Reference Lake and Rothchild1996).

Our theory also suggests hypotheses that operate at the individual level. We assume that individual choice to join protests is shaped by a combination of instrumental, normative, and psychological considerations. Instrumental logic suggests that personal interest considerations motivate the choice to participate in a protest. However, as Varshney notes, participating in a nationalist mobilization solely due to this logic would occur only in rare situations, such as when nationalist goals are close to being achieved and “much can be gained (or losses cut) by joining the bandwagon” (Reference Varshney2003, 94). Instrumental considerations, however, are constrained by social pressure (Lazarev Reference Lazarev2019, 673). Families, communities, organizations, and networks that organize and benefit from protests around ethnic grievances may impose social sanctions, including ostracism, on members who do not participate. Membership in social networks and organizations therefore also shapes the instrumental calculus on protest participation.

Individual decision to participate in nationalist mobilization is also shaped by noninstrumental considerations. As Horowitz and Klaus (Reference Horowitz and Klaus2020) note, psychological approaches to ethnic politics show that appeals to ethnic group level considerations related to status and deprivation are more likely to resonate due to “the psychic rewards that come from advancing in the social hierarchy” (39; see also Horowitz [2000]). In diverse and unequal societies, individuals “derive a sense of self-worth in part from where their community lies in the country’s social hierarchy,” and, as a result, their support for ethnic political mobilization is likely to increase in response to appeals that emphasize “group-level considerations related to status and deprivation” (Horowitz and Klaus Reference Horowitz and Klaus2020, 39). Moreover, value-based considerations of dignity and recognition make individual choice “relatively inelastic with respect to costs” (Varshney Reference Varshney2003, 83). This reasoning allows us to formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: After ethnic civil war, individuals who perceive that their ethnic group is discriminated—especially those who are more concerned about threats to their group’s security or their group’s power status—are more likely to participate in protests.

Although this theoretical framework emphasizes ethnic grievances, we do not negate the role of other factors highlighted in the literature on protests. In particular, an emphasis on grievances is not inconsistent with the logic of the resource mobilization or POS approaches, but rather it seeks to complement them (Simmons Reference Simmons2014). As we posit that ethnic grievances are more likely to generate protests in postconflict societies, we also recognize that collective action needs organizations and networks that mobilize people to join in protests. Moreover, our theory does not deny the role that changes in society and politics play in creating new opportunities for protest action. In this regard, we agree with Loveman who argues that “explanations for collective action involve multiple variables whose influence in particular instances of collective action is complexly and contingently interrelated” (Reference Loveman1998, 477).

Our theory’s predictions apply to deeply divided societies which have recently emerged from major ethnic civil war and where the presence of peacekeeping missions constrains the possibility of armed conflict recurrence. Although the salient political cleavage over which a civil war is fought can also be class based or ideological (Sambanis Reference Sambanis2001), we follow Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug in “restricting our substantive focus to groups defined through ethnic categorization rather than through other cleavages” (Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013, 38). This is in part due to the assumption that ethnic identity tends to be less elastic than other types of identities, and therefore “ethnic groups are more likely to face difficult-to-resolve bargaining problems” (Denny and Walter Reference Denny and Walter2014, 199; see also Rothchild and Hartzell [1999, 256]). Further, the theory is more likely to apply to postconflict political systems that allow for some level of free civic engagement.

Contentious Collective Action in Kosovo: A Brief Historical Background

To understand the contextual drivers of protests in Kosovo, we place its protest repertoires in a historical context. Protest repertoires are context specific and include a set of skills and activities that participants can choose to select and perform, often by experimenting and innovating (Alimi Reference Alimi, Porta and Diani2015; Tilly Reference Tilly2006).

Contemporary contentious politics in Kosovo began with Kosovo Albanian student protests in 1968, in which students made demands for national rights, equal rights for Albanians in federal Yugoslavia, better living conditions for students, and more job opportunities for Albanians (Hetemi Reference Hetemi2020, 95–96). Kosovo Albanian students also led massive protests in 1981, at the height of economic crisis in communist Yugoslavia. Kosovo had the status of an autonomous province of the Republic of Serbia within the Yugoslav federal state, even though the decentralization of the federation in 1974 had given autonomous provinces virtually the same powers as republics (Pula Reference Pula2004, 801). The 1981 protests started with student complaints about the quality of food at the University of Prishtina but soon shifted to demands that Kosovo be given the status of a republic within Yugoslavia (Hetemi Reference Hetemi2018). These protests had many causes, including grievances related to group political exclusion and economic grievances related to Albanian underrepresentation in higher-paid professions (Clark Reference Clark2000; Mertus Reference Mertus1999). In Serbia, the 1981 protests were interpreted as a sign of Albanian nationalism and “counter-revolutionary” to the Yugoslav ideals (Pula Reference Pula2004, 803). After a state of emergency, Yugoslav forces squashed the protests.

Concerns about ethnic group status underpinned the 1981 protests and their aftermath, in a context of economic crisis and political insecurity. While Albanians were worried about political exclusion within the Serb republic in Yugoslavia, ethnic Serbs were worried about status reversal if Kosovo Albanians gained more autonomy (Hetemi Reference Hetemi2020, 129). Kosovo Serbs also demonstrated in the 1980s, demanding “Serbia’s protection from Albanians” within the Serb republic (Hetemi Reference Hetemi2020, 199). In the late 1980s, Milosevic came to power using the perceived grievances of the Kosovo Serb minority in Kosovo—who despite having better economic and political access felt threatened by Albanians—and pushed for constitutional changes that reduced Kosovo’s autonomy. Milosevic’s campaign included attacks against media, populist rallies, and intimidation of Albanians. According to Mertus, in the eight years following the 1981 protests, “584,371 Kosovo Albanians—half the adult population—would be arrested, interrogated, interned or remanded” (Reference Mertus1999, 46).

Facing the loss of status, Albanians chose a strategy of pursuing independence by nonviolent civil resistance, in which participants did not use weapons or cause bodily harm to the opponents (Clark Reference Clark2000). The nonviolent resistance movement mobilized the participation of the vast majority of Albanians in Kosovo, including women (Chao Reference Chao2020). By 1992, the parallel state institutions of Kosovo Albanians under the leadership of Ibrahim Rugova halted demonstrations, fearing further violent repression. Notably, Albanian students of the University of Prishtina engaged in direct nonviolent demonstrations in 1997, as they were not able to study in the university premises but in private houses, garages, and basements. Demonstrating students started with demands for better education in university spaces and later sought political independence for Kosovo (Hetemi Reference Hetemi2020, 206–219). During the 1988–1997 period, therefore, Kosovo Albanians used mostly nonviolent means, such as protests, strikes, and boycotts in their civil resistance (Pula Reference Pula2004).

As Kosovo Albanians grew dissatisfied with the lack of progress by the nonviolent pursuit of independence, a small group of Albanians formed the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) and launched an insurgency in the mid-1990s. The harsh counterinsurgency campaign by Serbia increased the support for and membership of KLA among Kosovo Albanians, and by 1998 the conflict escalated into a fully-fledged war. To prevent further mass atrocities and the destabilization of the region, NATO intervened with airstrikes. Following a ceasefire, the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) was tasked with administering the territory and building local institutions. Our analysis focuses on protest events in postwar Kosovo, beginning in August 1999.

Protest Behavior in Postwar Kosovo

Because systematic data on protest behavior in Kosovo was unavailable, we compiled a new dataset based on archival analysis of media reports. To do so, we followed the example of the European Protest and Coercion Data (PCD) project (Francisco Reference Francisco2000). Specifically, we relied on information provided by the UNMIK Media Monitoring Archive, which includes summaries of media articles from numerous local and international media sources for the information of UNMIK personnel. These archives, which cover the period between August 1999 and December 2012, are publicly available (UNMIK 2012). The archives cover daily headlines and summaries of main events in Kosovo discussed in Albanian-, Serbian-, and English-based media, allowing us to leverage information from numerous sources.

Like PCD, KPD includes detailed information about each protest event.Footnote 3 Every event (such as a demonstration, strike, or petition) is sampled as a distinctive incident, irrespective of its duration, number of participants, target, or violence and property damage involved (Nam Reference Nam2006, 283). In addition to coding the type of protest event, the dataset records the event date, identity of protesters, the protest issue, demand or grievance, location, number of protesters, use of violence by the protesters or the state, and additional description of the event.Footnote 4 Using similar coding criteria as the PCD project enables us to compare Kosovo protest behavior with other countries. Table A1 in the Online Appendix lists the most frequently observed protest actions from August 1999 to December 2012. There are 848 unique protest events in KPD. Public demonstrations account for the largest share of contentious political actions at 74.4%, followed by strikes (8.7%) and petitions (6.7%). The number of protests peaked right after the conflict in 2000 with 142 events and then stabilized in a range between 84 in 2002 and 27 in 2007, the year before Kosovo declared independence.

Our findings contradict the hypothesis that postwar societies will experience a lower rate of protests. One way to compare protest behavior across countries has been to look at the yearly mean number of protest events, taking population size into account (Rüdig and Karyotis Reference Rüdig and Karyotis2014, 490; Nam Reference Nam2006). Between 1999 and 2012 Kosovo had 36.2 protest events per million inhabitants.Footnote 5 Contrary to the hypothesis that postwar societies will experience lower protest rates, Kosovo ranks higher than most European countries in protest events per million inhabitants (Rüdig and Karyotis Reference Rüdig and Karyotis2014, 490). Another way to compare protest activity has been to employ data from cross-national population surveys. European Values Survey data, which in 2012 included Kosovo, shows that 6.1% of Kosovo respondents claimed to have taken part in a demonstration in the past 12 months. This number is close to the 6.8% average of the 29 European countries involved in the study that year and is similar to neighboring countries in the Balkans (European Social Survey Round 6 Data 2012).Footnote 6

Because we were particularly interested in the categories of protest grievances or demands in Kosovo, we included detailed information on the protest issue, or the grievance topic of the protesters. Since we found no previous work that has coded postwar contentious political actions, we inductively coded for categories of issues observed, while also relying on existing typologies of protest grievance and demands in other contexts (Ortiz et al. Reference Ortiz, Burke, Berrada and Cortés2013). We grouped the categories around four main themes: economic justice, good governance demands, group security and transitional justice, and political system and group representation. Economic justice grievances focus on workers’ rights (salaries, jobs, pensions), as well as economic policy (privatization, subsidies, trade policy, and taxes). Good governance demands included free and fair elections, government transparency, and good governance concerns such as corruption, as well as demands for better public services. Group security and transitional justice included concerns or grievances about ethnic group security, violence toward coethnics, and protests related to transitional justice such as the release of war prisoners, arrest of wartime veterans, and missing coethnics from the war. Finally, political system and group representation grievances included protests about the unresolved final status of Kosovo and demands for Kosovo to become independent (by Albanians) or remain in Serbia (by Serbs), dissatisfaction with the international administration, and resistance to newly constructed state institutions. Table 1 below summarizes the three most commonly observed protest issues in each of the subcategories for protest issues in the dataset.

Table 1. The Most Commonly Observed Protest Grievances and Demands in Kosovo (1999–2012)

Note: % indicates the share of issue as a percentage of the total number of observations in the dataset. SOE: Socially Owned Enterprises; KFOR: NATO-led international peacekeeping force in Kosovo; EULEX: European Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo; PISG: Provisional Institutions of Self-Government. Number of Observations: 848. Not included are 95 protest events for which there was insufficient information about issue or protester grievance (11.2% of total events).

Source: KPD.

The protest event data summarized in Table 1 support our hypothesis that perceived ethnic grievances—particularly perceived threats to group security or power status—generate more protest mobilization than other categories of grievances. Protests mobilized around group security or transitional justice constitute the largest share of events in the dataset (33.8%). Within that category, ethnic grievances centered around transitional justice are prominent, especially in the early postwar period, as large protests occur to support the release of Albanian war prisoners held in Serbia. In addition, the Association of KLA War Invalids and Veterans launched several large demonstrations following the arrests of ex-KLA members for alleged war crimes in 2002 and 2003. The fate of missing persons from the war also figures prominently in the dataset. Similarly, a large number of protest events occur around issues related to postconflict security issues. Twenty-six protests in our dataset, the majority of them by ethnic Serbs, occur after the arrest of a coethnic by Kosovo local institutions or the international peacekeepers. A similar number of protest events occurs following the murder of a coethnic. The analysis of the claims made by the protesters reveals that these individual security incidents are viewed and interpreted as threats to the whole ethnic group living in the community.

Protests about the postwar political system and related concerns about group status were also widespread (32.8%). As the international administration and Kosovo Albanians engaged in the construction of state institutions (Skendaj Reference Skendaj2014), 84 protest events (9.9% of the total) occur against the different international institutions engaged in peace and state building, such as UNMIK or the EU Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX). In organizing protests against international administration of Kosovo, the Self-Determination Movement framed its opposition through a critique of neocolonial rule by UNMIK (Visoka Reference Visoka2017, 115) or perceived violation of sovereignty by EULEX (Mahr Reference Mahr2018). Further, Kosovo Serbs protested and resisted these new institutions and Kosovo’s statehood, as they feared the loss of their privileged group status in a Kosovo governed by Albanians. They used protests and boycotts to resist the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government (PISG), the local institutions created under the UN administration, as well as Kosovo institutions after the declaration of independence in 2008.

Finally, the unresolved final status of Kosovo mobilized both Kosovo Albanians and Serbs. Before 2008, Kosovo Albanians held demonstrations and signed petitions demanding independence or unification with Albania. After the declarations of independence in February 2008, they protested against municipal decentralization in Kosovo that would provide more enhanced autonomy to Serb municipalities, as well as against dialogue with Serbia, when decentralization and dialogue were perceived as threatening Kosovo’s sovereignty. On the other hand, Kosovo Serbs in 2008 and 2009 engaged in frequent protests against Kosovo’s independence, as well as boycotting and resisting Kosovo’s state institutions. Serb protests against state building efforts remained the most frequent form of ethnic grievance expression through 2012. Broadly speaking, Kosovo Albanians and Serbs viewed the issue of sovereignty through the prism of addressing group grievances and maintaining group security and status via self-rule (Kelmendi and Radin Reference Kelmendi and Radin2018).

As Figure 1 indicates, grievances associated with ethnic groups security and status concerns continued to dominate even after Kosovo declared its independence in 2008, although there was a shift from issues focusing on transitional justice and security to institutional resistance (see Fig. 2). In contrast, good governance demands accounted for only 9% of the postwar protest events, with protests against frequent power shortages constituting the largest share in this category. Economic issues, on the other hand, accounted for slightly more than 11% of total observations, the bulk of which focused on demands for jobs and higher salaries or pensions. Once the status was settled in 2008, we notice more strikes among Kosovo Albanians’ civil servants, such as health workers, police, the judiciary, and government staff that demand better salaries and working conditions.

Figure 1. All Protest Grievance/Demands in Kosovo Over Time (Source: KPD)

Figure 2. Ethnic Grievance/Demands in Kosovo Over Time (Source: KPD)

Grievances around postwar security and transitional justice, or the postwar political system and representation, dominate every year for both Albanians and Serbs, although they are more salient for Serbs (see figs. A1 and A2 in the Online Appendix). In postwar Kosovo, Serbs have used both violent and nonviolent methods to resist PISG and then Kosovo’s state institutions. The Serbian National Council, which viewed itself as the representative of Kosovo Serb interests, was a key organizer in many of these protests. In addition to protests, the Serb minority has engaged in everyday boycotts of Kosovo’s state institutions, which they view as representing Albanian rule. Such resistance is demonstrated through the use of Serb curricula in schools, Serb media, as well as the refusal of Kosovo Serbs to integrate in the Kosovo police and the judiciary (Fort Reference Fort2018).

This distribution of protest grievances and demands in postwar Kosovo is different from global patterns of protests. Ortiz et al. (Reference Ortiz, Burke, Berrada and Cortés2013) find that the majority of world protests (58%) focus on economic justice issues, such as poverty, jobs, and access to public services. Only 1% of global protests focus on sovereignty issues in which various groups demand autonomy or self-rule. The distribution of protest grievances in postwar Kosovo is therefore distinct in that group security and status are much more prevalent than those about good governance demands or economic justice.

Another way to test whether ethnic grievances are more likely to generate political protest than other categories of grievances is to investigate variation in the number of participants in protests (Biggs Reference Biggs2018). In demonstrations recorded by KPD, estimates of protest size are reported in only 242 cases. As Table A2 in the Online Appendix shows, on average, demonstrations organized around ethnic grievances in Kosovo mobilized significantly more participants than those organized around good governance or economic justice. The mean demonstration size organized around ethnic grievances was 6,608 participants, whereas that number was 986 for protests mobilized around good governance demands and 731 for those centered on economic justice.

This emphasis on ethnic group security and group status in Kosovo can be explained, to begin with, by the fact that both Albanians and Serbs tend to have high levels of ethnonationalism (Dyrstad Reference Dyrstad2012). Political goals for groups during wartime remain very popular, and people worry about ethnic domination and security (Kelmendi and Radin Reference Kelmendi and Radin2018, 987), as there are political and economic costs to being treated as a minority (Skendaj Reference Skendaj2016). Evidence from quarterly UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) public opinion surveys conducted in Kosovo during this period supports this. Until 2008 the majority of Kosovo Albanians ranked uncertainty over Kosovo’s final status as their paramount concern (UNDP 2007). As their worries about final status diminished following independence, we observe an increase in protest events focusing on economic and governance issues. Kosovo Serb public opinion on the most pressing problem facing Kosovo is more divided during this period. However, even among Serbs, the top concerns were related to group security and status: uncertainty over the final status, tense interethnic relations, and public and personal security (see figs. A3 and A4 in the Online Appendix).

Public opinion data from UNDP Kosovo Early Warning or Public Pulse between 2005 and 2012, however, indicates that people in postwar Kosovo were also concerned about other issues, particularly poverty and unemployment (UNDP 2009). Such public opinion data suggests that the pattern of protest behavior in postconflict Kosovo cannot entirely be explained by grievances alone (see Figs. A5 and A6 in the Online Appendix). The presence of organizations that tapped on perceived ethnic grievances, like the Self-Determination Movement, or those that were motivated by wartime grievances, such as Mothers’ Appeal, played a key role in mobilizing protests. Among Kosovo Albanians, the Self-Determination Movement organized some of the largest political demonstrations (Kelmendi Reference Kelmendi and Agani2012; Vardari-Kesler Reference Vardari-Kesler2012, 158). Organizations emerging from wartime networks (such as the KLA Veterans Associations) were also active in protesting the legal prosecution of their members and demanding the achievement of their wartime agenda: the independence of Kosovo.

In contrast to organizations such as the Self-Determination Movement or the Veterans Associations, on the other hand, internationally sponsored NGOs in Kosovo appear only infrequently as organizers of protest events in KPD. They generally focused on good governance and economic issues but suffered from weak organizational structures, poor public image, and weak networks and capacity to join coalitions (Ceku Reference Ceku and Haskuka2008, 142; Kelmendi Reference Kelmendi and Agani2012). Finally, while weakened and co-opted, workers’ unions were responsible for various strikes and protests for higher salaries and better workers’ rights.

Thus, while grievances are important, our analysis of the Kosovo case also confirms the importance of organizations and networks that mobilize people to join in protests. Scholars have noted that the ideology, structure, and resources of organizations influence their choice of collective action as well as their tactics and behavior (McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Dalton Reference Dalton1994). An organization’s orientation and goals—whether it is seen as a “pragmatic, reform-oriented NGO or a radical uncompromising outsider” influences its tactics (Hadden Reference Hadden2015, 65). Movements that adopt the ideology of radical outsiders attract and mobilize participants that will tend to use contentious actions such as protests (Snow and Benford Reference Snow, Benford, Bert, Kriesi and Tarrow1988). Moreover, in terms of resources, radical movements are likely to rely on mobilizing participants, and not on outside donors (Schlozman and Tierney Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986). Kosovo’s postconflict setting confirms this, as we observe that organizations with more radical ideological nationalist orientation mobilized in noninstitutionalized political action. On the other hand, organizations that adopt pragmatic reformist goals, such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) were less likely to engage in contentious action (Kelmendi Reference Kelmendi and Agani2012).

The widespread participation of Kosovo Albanians in various forms of nonviolent protest and resistance prior to and during the war also shaped postconflict protest repertoires.Footnote 7 After he was released from prison, Albin Kurti used his past experience as a student activist in the second half of the 1990s to lead the Kosovo Action Network and subsequently the Self-Determination Movement (Vardari-Kesler Reference Vardari-Kesler2012, 158).Footnote 8 The prewar and wartime experiences of the Kosovo conflict also likely shaped individual attitudes on the issues that are more likely to mobilize protest participation. In 1988 and 1989 there were miners’ strikes demanding restoration of Kosovo’s autonomy, and subsequently in 1990 the Independent Trade Unions of Kosovo (BSPK) organized a general strike to protest the firing of Albanian workers (Pula Reference Pula2004, 811). In the 1990s, student associations were deeply involved in organizing demonstrations demanding the status of republic or independence for Kosovo (Hetemi Reference Hetemi2020). The emphasis on these ethnic status issues continues in the postwar context. We noticed, for example, that student associations were more likely to engage in protests about ethnic grievances than they were about issues such as the quality of education.Footnote 9

Factors emphasized by the political opportunity structure approach are also necessary to explain protest behavior in Kosovo. The declaration of independence in 2008 constituted a shift in the governance structure in Kosovo from international administration to supervised self-rule. After the declaration of independence, the share of protests about economic issues or good governance increases among Albanians, although group security and group status concerns remain the dominant category. Unsurprisingly, no such change is observed among Serb protesters. However, whereas concerns about ethnic insecurity dominate among Kosovo Serbs before independence, resistance to Kosovo institutions emerge as the key focus of Kosovo Serb protests after 2008.

Thus, while we also find support for the alternative explanations of networks and political opportunity structures, ethnic grievances remain a central driving force of protest behavior in Kosovo. Although exogenous institutional and political processes in Kosovo, such as international supervision and the declaration of independence, influenced levels of protest activity, concerns about ethnic group security and group status were more likely to drive people to protest during both international administration and postindependence periods. Moreover, while certain networks and organizations played a key role facilitating protests in Kosovo, such networks were most successful in facilitating mobilization when they tapped on perceived ethnic grievances. For example, the Self-Determination Movement was able to mobilize a larger number of protesters in demonstrations centered around ethnic group grievances and status than in demonstrations against corruption.Footnote 10 Facing potential loss of status and feeling insecure about the security of their ethnic group, Albanians and Serbs in Kosovo prioritized expressing ethnic grievances over economic or governance ones, even when the networks organizing the protests were the same.

Determinants of Individual Participation in Protests

In this section, we investigate the determinants of variation in individual protest participation in Kosovo. Specifically, we test Hypothesis 2 outlined in the theory section above as well as alternative hypotheses drawn from the theoretical frameworks developed to explain individual protest participation in stable democracies. Our data source is the ESS survey conducted in Kosovo in 2013.Footnote 11 The ESS surveys are designed to be representative of the country’s population, cover a wide spectrum of topics, and, importantly, include questions about respondents’ engagement in different forms of political participation.

In order to code our main dependent variable, Demonstration participation, we use the answer to the following item in the survey: “There are different ways of trying to improve things in Kosovo or help prevent things from going wrong. During the last 12 months, have you done any of the following? Have you taken part in a lawful public demonstration?” The responses were coded into a dichotomous variable: 1 for “Yes” (8.3% of survey respondents) and 0 for “No” (91% of all the respondents). Those who refused to answer or stated that they do not know (0.7% of all the respondents) were treated as missing values and dropped from the main analysis. We employ and discuss the results of logit models, using fixed effects to control for unobservable factors across Kosovo’s seven different administrative regions.

Independent Variables

Hypothesis 2 expects that perceived ethnic grievances will motivate protest mobilization more than other categories of grievances, such as economic grievances. Thus, our models included a measure of respondents’ feelings about their household’s income (Income dissatisfaction) to proxy for economic grievances, which ranges from 1 (living comfortably on present income) to 4 (very difficult on present income). Further, we included a variable that captures respondents’ perception of ethnic discrimination (Ethnic discrimination). This measure assumes a value of 1 if respondents declared that they were a member of a group that is discriminated against in Kosovo based on ethnicity, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 12 We further included another variable that captures respondents’ perception of nonethnic discrimination (Nonethnic discrimination), which assumes a value 1 if respondents declared that they were a member of a group that is discriminated against in Kosovo based on nonethnic grounds, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 13 The reference category includes respondents who declared that they were not a member of a group that is discriminated (No group discrimination).

Our review of existing theories of protest activity above noted that, at the microlevel, the analysis of protest participation should pay attention to sociodemographic and network resources, motivations, and attitudes toward political institutions. To account for sociodemographic characteristics that capture individual resources, our models contain variables measuring respondents’ age (Age) and the income decile (Income) that their household belongs to. In addition, we employ a set of dichotomous variables comparing women and men (Sex); those who had completed university education with those who had not (University education); married individuals with those who were not married (Married); and the employed with the unemployed (Unemployed). To account for the effect of networks, we include a set of dichotomous variables coded as 1 if respondents declared that in the last 12 months they worked in a political party or action group (Party worker), worked in another organization or association (NGO worker), were a member of a trade union or similar organization (Trade unionist), or worked in the public sector (Public sector employee), and 0 otherwise.

On respondents’ perception of and support for the workings of political institutions, we consider several variables. First, we include respondents’ reported levels of trust for Kosovo’s parliament (Trust in parliament) and political parties (Trust in parties). Second, we employ an item that measures satisfaction with the way democracy works in Kosovo (Satisfaction with democracy) and another one that gauges the levels of satisfaction with the current government (Satisfaction with government). Finally, to account for political party preferences, we also included a set of dichotomous variables that were coded as 1 if respondents declared that they felt closer to a particular political party and 0 otherwise.

To account for the effect of general motivational attitudes, we consider three variables. First, we include respondents’ level of trust in other people (Interpersonal trust), a variable that goes from 0 (“One can’t be too careful”) to 10 (“Most people can be trusted”). Second, we employ respondents’ reported levels of interest in politics (Political interest), which ranges from 1 (“not at all interested”) to 4 (“very interested”). We also control for levels of civic engagement, broadly construed. Specifically, to gauge individuals’ propensity to engage in civic activities in general, we include a dichotomous variable that measures individual involvement in work for voluntary or charitable organizations (Voluntarism), coded 1 if respondents answered that they were involved in work for voluntary or charitable organizations at least once a week, month, or every three months and 0 otherwise.

Findings

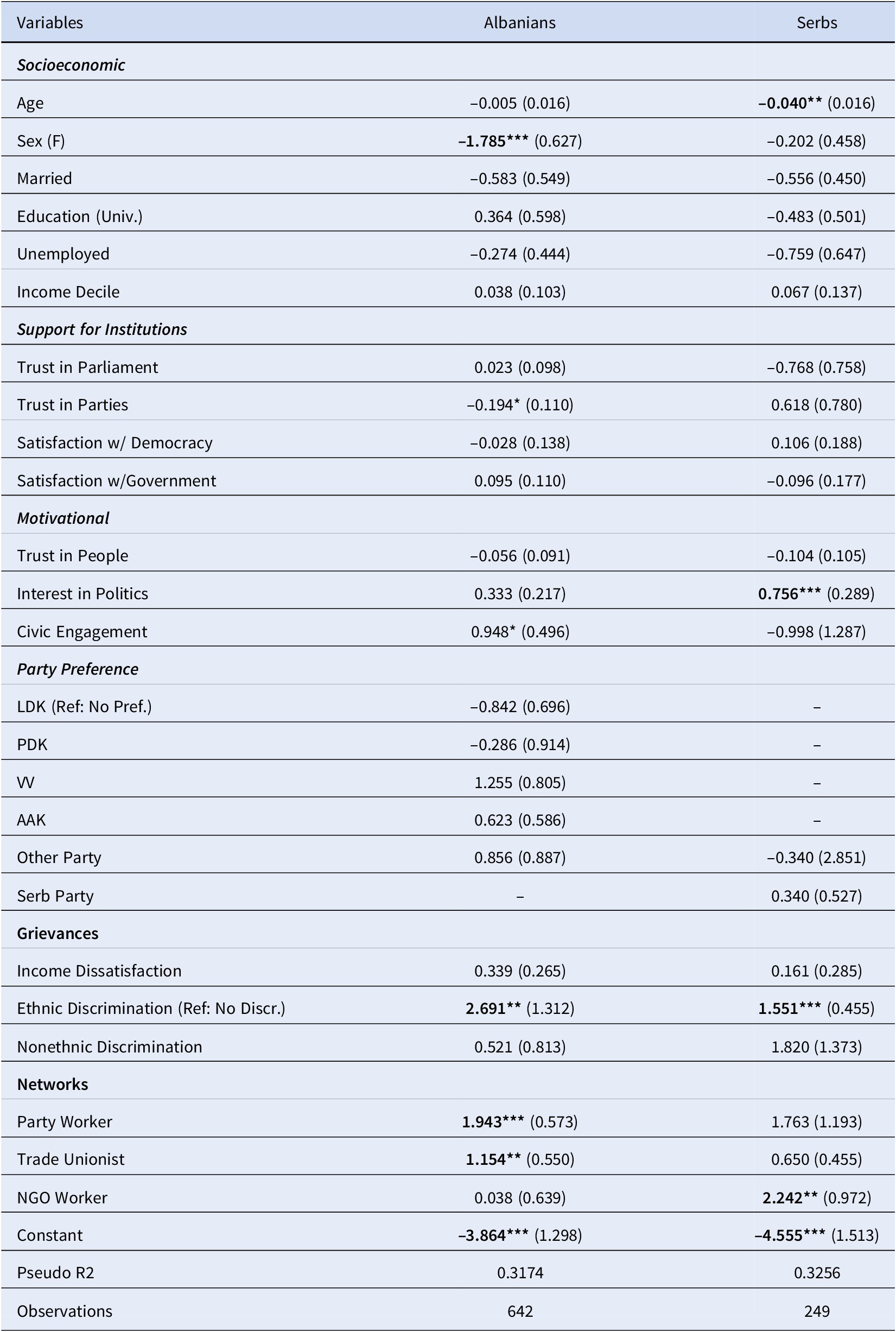

Table 2 presents the results of the logistic regression analyses for demonstration participation in Kosovo. In order to account for the possibility that ethnic grievances—and other determinants of participation in protests—function differently for Albanians and Serbs in Kosovo, we conduct two analyses of subsamples, one only containing ethnic Albanians and the other ethnic Serbs.Footnote 14

Table 2. Logit Estimation Results for Demonstration Participation in Kosovo (2012)

Note: Robust standard errors in brackets. All models include region fixed effects (reference: Prishtina) – region coefficients and standard errors not included to save space; LDK = Democratic League of Kosovo; PDK = Democratic Party of Kosovo; VV = Self-Determination Movement; AAK = Alliance for Future of Kosovo (reference: no party preference); Statistically significant coefficients at the 0.05 level in bold. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

In line with our hypothesis, perceived ethnic grievances are more likely to predict protest participation than individual economic concerns or perceived nonethnic group grievances. Holding other variables at their means, Albanian respondents who described themselves as being members of a discriminated ethnic group in Kosovo were 17% more likely to have participated in a lawful public demonstration than those who did not consider themselves a member of a discriminated group. Similarly, Serb respondents who perceived themselves as belonging to a discriminated ethnic group were 13% more likely to have participated in a public demonstration. As predicted by our theory, there is a positive and statistically significant association between individual perception of ethnic group grievance and participation in public demonstrations in Kosovo.

Most socioeconomic variables, including marital status, education, employment status, and income are poor predictors of protest participation. We find evidence that Albanian women are less likely than men to participate in demonstrations and that age is negatively associated with protest participation for Serbs, but the effect is substantively small in both cases. Support for institutions plays no role. None of the variables that gauge respondents’ support for Kosovo’s institutions, including trust in parliament, trust in parties, satisfaction with democracy, and satisfaction with the national government, are good predictors of the likelihood of demonstration participation for Kosovo Albanians or Kosovo Serbs.

We find mixed evidence for motivational variables. While we observe that Serb respondents who reported higher levels of interest in politics were more likely to have participated in a demonstration, the same relationship between interest in politics and demonstration participation is not found in the Kosovo Albanian model. Moreover, the propensity to trust other people or frequent involvement in work for voluntary or charitable organizations were not good predictors of the likelihood to participate in demonstrations in either model.

The results also suggest the significance of networks. Kosovo Albanians who in the last 12 months had worked in a political party or action group, as well as current and past members of trade unions, were significantly more likely to declare that they participated in a demonstration. Kosovo Serbs who had worked for an NGO in the last 12 months were also significantly more likely to declare that they participated in a demonstration. Just like at the societal level, our analysis shows that membership in networks is also associated with individual-level protest participation.

In order to verify the robustness of the regression results, we ran a wide range of alternative models. Altering model specifications, however, did not change the main results (see Tables A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9 in the Online Appendix). Specifically, we obtained similar results regarding the association between ethnic discrimination and the likelihood of participation in demonstrations by employing probit analysis, or using alternative cutoff points for education (high school), age (under 30), and civic engagement (at least once in six months) (Tables A3 and A5). Further, the results did not change when we added variables that measured respondent religiosity, self-placement in the left to right scale, employment in the public sector, or student status (Tables A4 and A6).Footnote 15 Perceived ethnic grievances have a positive and statistically significant effect on boycott participation as well (Table A7). Finally, combining the two subsamples and conducting an analysis of the entire Kosovo population sample also generates similar results (Tables A8 and A9).

The discussion of the logistic regression analyses is in line with patterns of protest behavior observed in the analysis of protest event data. Perceived ethnic group discrimination is a significant predictor of protest participation, as is membership in networks.

Conclusion

This article presented a novel theory of protest behavior in postwar societies and tested it with new data from Kosovo. Our analysis of protest event data from Kosovo revealed that most contentious collective action included public demonstrations, and most protests were motivated by ethnic grievances that reflected concerns about ethnic group security and status. Kosovars were no less likely to participate in protests compared to other European citizens. The distribution of protest grievances and demands in postwar Kosovo, however, is different from global patterns of protests, which center around economic justice concerns. Kosovo citizens also cared about economic and good governance issues such as unemployment, poverty, and corruption. However, protest events mobilized around such issues were significantly rarer. Protest size, as measured by the number of participants, tended to also be larger for protests organized around ethnic grievances. This finding was consistent with our theory’s emphasis on categories of grievances that mobilize people. Prewar protest repertoires of nonviolent marches also shaped protest behavior, as did specific networks and organizations and changing political opportunities in the postwar setting. Using Kosovo survey data from the 2012 ESS survey, the article also took a first step toward testing hypotheses about the individual determinants of protest participation in postwar settings. The survey responses of Kosovo citizens supported our hypotheses emphasizing the role of perceived ethnic group discrimination while also confirming the role of other variables, such as that of networks.

Our article has policy implications for peacebuilding. In postwar settings like Kosovo, international actors invest heavily in new civil society organizations that provide services and advocacy, yet they are distrustful of local organizations that make nationalist claims. However, such organizations act as important networks that mobilize people to protest, and external actors should seek creative ways to institutionally engage with them. Ethnic grievances and status insecurity may trump concerns for good governance and anticorruption in divided postwar societies. More broadly, local and external actors engaged in postwar peacebuilding and good governance should recognize the potency of group status and security concerns and place more efforts to address them via institutional innovation, persuasion, and dialogue.

The findings of this article point to several opportunities for future research. First, our theoretical and empirical investigation focused on deeply divided societies emerging from ethnic civil war. Future scholarship should investigate the relationship between protests and group security and status concerns in postwar societies where the salient political cleavage is class-based or ideological. Second, the determinants of protest participation in postconflict settings may be correlated with variation in conflict experiences. Further study of the effect of wartime experience at the individual or community level will be valuable. Third, future work should examine how political entrepreneurs and organizations and networks engage in framing, reframing, and mobilizing around ethnic grievances.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2022.7.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rania Marwan and Mingyang Su for their valuable research assistance with this project. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosures

None.