INTRODUCTION

We can observe in the business landscapes of emerging and transforming economies (ETEs) many examples of successful business models that were replicated from developed economies (Lee, Kwon, Lee, & Park, Reference Lee, Kwon, Lee and Park2016; Luo, Sun, & Wang, Reference Luo, Sun and Wang2011; Shenker, Reference Sanchez and Ricart2010; Wu, Ma, & Shi; Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010). Examples include budget hotel chains (some proven models in developed economies are Super 8, Motel 6, Ibis, and Travelodge), pharmacy chains (CVS Pharmacy, Walgreens, and Boots), convenience store chains (7-Eleven), quick service restaurant (QSR) chains (McDonalds and KFC), ecommerce platforms (Amazon, Expedia), ride-hailing platforms (Uber, Lyft), and home-stay platforms (Airbnb), among others. In some instances, it is the successful developed country organizations themselves such as McDonalds and KFC who enter the ETEs and replicate their business models in these newer contexts. In other cases, it is local entrepreneurs in the ETEs who draw inspiration from the developed country organizations and replicate the successful business models, either entirely or partially.

When a developed country organization such as McDonalds, KFC, or Ibis enters ETEs, the replication of its successful business model (whether with minimal or significant adaptation to the local context) is based on intra-organizational knowledge transfer across geographic boundaries and new organizational learning in the ETEs (Brock & Yaniv, Reference Brock and Yaniv2007; Jonsson & Foss, Reference Jonsson and Foss2011; Kumar, Gaur, Zhan, & Luo, Reference Kumar, Gaur, Zhan and Luo2019; Wang, Zhu, & Terry, Reference Wang, Zhu and Terry2008; Winter, Szulanski, Ringov, & Jensen, Reference Winter, Szulanski, Ringov and Jensen2012). However, when local entrepreneurs from ETEs replicate successful business models of developed country organizations, their replication is based on inter-organizational learning, usually in the absence of explicit knowledge transfer actions from the possessor of the knowledge and capabilities. This inter-organizational learning is based on vicarious learning (Banerjee, Prabhu, & Chandy, Reference Banerjee, Prabhu and Chandy2015; Baum, Li, & Usher, Reference Baum, Li and Usher2000; Denrell, Reference Denrell2003; Manz & Sims, Reference Manz and Sims1981) such as observation of others’ experiences, formal study through available documentation and through consultants and advisors, partnering with the partner organizations (such as vendors) of the developed country organizations, and the recruitment of employees from the developed country organizations. We refer to this replication of business models through inter-organizational learning as secondary business model innovation (SBMI), following Wu et al., (Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010). Based on our review of the literature, we find that while there have been a number of studies of replication of organizational routines (Szulanski & Jensen, Reference Szulanski and Jensen2008; Winter, Reference Winter and Montgomery1995; Winter & Szulanski, Reference Winter and Szulanski2001) and vicarious learning across organizations (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Prabhu and Chandy2015; Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988; Posen & Chen, Reference Posen and Chen2013), there have, to our knowledge, been no studies to date on the mechanisms underlying SBMI. Our research addresses this gap in the literature. We propose that SBMI is a specific case of the broader construct of creative imitation (Drucker, Reference Drucker1985; Kim, Reference Kim1997; Lee & Zhou, Reference Lee and Zhou2012; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kwon, Lee and Park2016; Levitt, Reference Levitt1966; Shenkar, Reference Shenkar2010; Valdani & Arbore, Reference Valdani and Arbore2007; Yu, Reference Yu2000) through vicarious and contextual learning.

SBMI is therefore the result of learning, i.e., absorbing knowledge and information of pioneers’ business models, combining it with the entrepreneurs’ own knowledge stock and flows, and deploying this learning, with adaptations, in new contexts. Unlike learning within organisations, where first-hand information about existing business models is available and resources are ample to support knowledge transfer, entrepreneurs and latecomers, especially those from emerging economies, face challenges in accessing related knowledge of other companies’ business models. Therefore, our central objective in this article is to further develop the concept of SBMI and understand the mechanisms through which it takes place.

We do this through the in-depth study of two quick service restaurant (QSR) chains, one in China and the other in India, set up by two local university-educated urban entrepreneurs. Both the QSR chains were based on regional ethnic dishes, which had hitherto been offered to consumers mainly by fragmented street-side vendors, who prepare dishes with authentic local taste albeit often under less than hygienic conditions. The two entrepreneurs that we studied decided to take these proven ethnic dishes to market and then grow the business through the QSR model. At the same time as they committed to maintaining the authentic taste of the local dishes, they decided to build chains of QSRs based on the business models of MNCs, such as McDonalds and KFC, which had been present in China and India for several years before the entrepreneurs set up their ventures.

Our focus is on the business model innovations that Chinese and Indian entrepreneurs introduced to grow their QSR chains to 1,400 and 300 outlets, respectively. Both entrepreneurs drew inspiration from and benefited to varying degrees from infrastructure, concepts, practices, and employees developed by leading QSR brands in China and India, both international and domestic. We build on the incipient but highly important SBMI concept and outline in detail how it played out in the ventures of the Chinese and Indian entrepreneurs, who were the subjects of our study. We then look at the SBMI process and identify the various mechanisms that the entrepreneurs relied on to learn about the successful business models.

The remainder of the article flows as follows: we first provide an overview of the literature on business models, business model innovations in emerging economies, creative imitation, and SBMI. We then describe our methods for data collection and analysis followed by a brief overview of our subject organizations. We describe the business models of our two subject organizations using an analytical framework developed by Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013). In our findings and discussion sections, we explain the differences (creative or non-imitative aspects) and similarities (imitative aspects) between the business models of the pioneers and those of our subject organizations. We then argue that SBMIs could be based on a combination of inspiration and vicarious learning, including building linkages to existing resources and capabilities created by other organizations. We then present a theoretical framework to explain how SBMI takes place. We conclude with implications of our study for the creative imitation literature and for practice, acknowledge its limitations and suggest future avenues for research on this topic.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Business Models and Business Model Innovations

The term business model (BM) has its origins in the writings of Peter Drucker (Reference Drucker1985). Business models are the basis of company success (Afuah, Reference Afuah2003; Amit & Zott, Reference Amit and Zott2001; Morris, Schindehutte, & Allen Reference Morris, Schindehutte and Allen2005) and are fundamentally about how an organization takes its product or service offerings to market. According to Zott and Amit (Reference Zott and Amit2010), a business model is a system of interdependent activities that transcends the focal firm and spans its boundaries. Teece (Reference Teece2010: 179) notes that ‘a business model articulates the logic, the data and other evidence that support a value proposition for the customer, and a viable structure of revenues and costs for the enterprise delivering that value’. There is an agreement that BMs span both the internal workings and external interfaces of the firm (Schneider & Spieth, Reference Schneider and Spieth2013) and need to address both the value creation and value capture aspects (Baden-Fuller & Mangematin, Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013).

Replicating a product innovation is relatively easy, but replicating a business model (an interdependent system of activities) is not easy as competitors may need to make many changes and ensure that these changes are consistent with rest of their activities. Thus, innovation at the level of the business model has the ability to deliver a long-term competitive advantage to the innovator (Amit & Zott, Reference Amit and Zott2012).

Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013) propose a framework that helps us understand business models as a particular kind of configuration that is cognitively manipulable. This outlook suggests that business models are not real phenomena; rather they should be considered cognitive devices that help us establish the cause and effect relationships between the different elements of the business within and outside the firm. The benefit of this framework is that it can be generalized across contexts. The four dimensions that Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013) propose are: customer sensing or customer identification, customer engagement, monetization, and value chain and linkages.

While research on BMs and BMIs has a fairly long history, that on BMI with a specific focus on ETEs is at a more incipient stage. Sanchez and Ricart (Reference Sanchez and Ricart2010) studied business model innovations in low income markets and identified two types, the first referred to as isolated business model, which relied primarily on the resources and competencies of the focal firm to exploit opportunities and the second referred to as interactive, which needed linkages to be built between the focal firm and external organizations in the ecosystem that were providers of valuable complementary resources and capabilities. One major implication of the differences between the two types is that with isolated business models, the speed of opportunity exploitation is high, whereas there is necessarily an exploratory phase with interactive business models where the focal firm goes through a process of learning along with its partners within the ecosystem.

Creative Imitation and Secondary Business Model Innovation

The concept was initially proposed by Levitt (Reference Levitt1966) as ‘innovative imitation’, i.e., not only copying existing products but also reworking and improving them with new characteristics. Drucker (Reference Drucker1985) noted that instead of producing or innovating new products, creative imitation is refining and improving existing products. Some studies have defined creative imitation as adding new value to the existing products/services for differentiation (e.g., Kim, Reference Kim1997; Lee & Zhou, Reference Lee and Zhou2012; Shenkar, Reference Shenkar2010; Valdani & Arbore, Reference Valdani and Arbore2007; Yu, Reference Yu2000). By exploiting latecomer advantages, including but not limited to shared experience and enhanced market knowledge, free rider effects, avoidance of trials and errors, and information spill-over (Cho, Kim, & Rhee, Reference Cho, Kim and Rhee1998; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010), as well as implementing creative imitation of the pioneers’ products/services, latecomer firms (LCFs) can reduce the risks of innovation and at the same time realise some of its benefits (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kwon, Lee and Park2016).

Most previous imitation-related studies were products/services-focused (e.g., Drucker, Reference Drucker1985; Levitt, Reference Levitt1966; Schnaars, Reference Schnaars1994; Shankar, Carpenter, & Krishnamurthi, Reference Shankar, Carpenter and Krishnamurthi1998), with studies of imitation in business models starting in 2010 (e.g., Casadesus-Masanell & Zhu, 2013; Shenkar, Reference Shenkar2010; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010). The same trends can be observed in creative imitation studies. Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Kwon, Lee and Park2016) proposed that a business model imitation can be considered as creative imitation if there is some innovation leading to the creation of new value. This is similar to the terminology ‘secondary business model innovation’ (SBMI), which has been proposed by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010), and refers to the replication of existing business models from developed countries by emerging country organizations, with adaptations to satisfy local customers’ demands, usually accompanied by new value propositions in the offerings (Mitchell & Coles, Reference Mitchell and Coles2003). SBMI can occur across organisations, as well as across industries. This article focuses on cross-organisation SBMI within the QSR sector.

Both Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010) and Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Kwon, Lee and Park2016) use several well-known companies as case studies to illustrate SBMI, in terms of how these companies created and captured value. However, there has been as yet no detailed discussion either on the process or on the mechanisms for achieving cross-organisation SBMI. SBMI could be considered the result of learning, i.e., absorbing knowledge and information of pioneers’ business models and deploying this learning, with adaptations, in new contexts. Unlike learning within organisations, where first-hand information about existing business models is available and resources are ample to support knowledge transfer, entrepreneurs/latecomers, especially those from emerging economies, face challenges in accessing related knowledge of other companies’ business models. Therefore, we attempt to connect the organisational learning literatures with SMBI studies to fill this research gap.

As late entrants usually suffer from ‘liability of newness’ (Posen & Chen, Reference Posen and Chen2013; Stinchcombe, Reference Stinchcombe and March1965), and are constrained by limited resources, including knowledge and capabilities, some scholars have suggested that late entrants should overcome this liability by learning vicariously from incumbents (e.g., Levitt & March, Reference Levitt and March1988; Posen & Chen, Reference Posen and Chen2013). Past studies have also revealed the importance of vicarious learning, not only in reducing LCFs’ exploration costs to draw valuable information and knowledge from incumbents (March, Reference March1991; Levinthal & March, Reference Levinthal and March1993), but also in supplementing LCFs’ own experience when imitating and adopting new practices and technologies from incumbents (Baum et al., Reference Baum, Li and Usher2000; Srinivasan, Haunschild, & Grewal, Reference Srinivasan, Haunschild and Grewal2007).

Two major mechanisms to learn vicariously have been discussed in past studies. One is observation. For example, Simon and Lieberman (Reference Simon and Lieberman2010) studied the effects of vicarious learning by magazine publishers, through observation of rivals’ websites, on their technology adoption decisions; Gittelman and Kogut (Reference Gittelman and Kogut2003) investigated how US biotechnology firms learn by observing competitors’ patents and publications; Baum et al. (Reference Baum, Li and Usher2000) found that firms operating multi-location businesses choose acquisition locations by observing selections of other similar firms that have already achieved a large scale; Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Kwon, Lee and Park2016) explained how Lei Jun, the founder of Xiaomi, acquired knowledge through observing leading companies’ strategies. Some scholars noted that firms learn vicariously by observing others’ failures (Denrell, Reference Denrell2003; Kim & Miner, Reference Kim and Miner2007). Another mechanism of vicarious learning is through incumbent firms’ employees. For example, knowledge flow may occur by board interlock (Tuschke, Sanders, & Hernandez, Reference Tuschke, Sanders and Hernandez2014) and employee mobility (Corredoira & Rosenkopf, Reference Corredoira and Rosenkopf2010), via personal relationships with other firms’ employees (Ingram & Roberts, Reference Ingram and Roberts2000), or through industry conferences (Keeble & Wilkinson, Reference Keeble and Wilkinson1999).

Most vicarious learning studies have discussed the topic in the context of replication and adoption of new technologies and managerial/strategic practices, but few have focused on the context of business model imitation and innovation. In the process of SBMI, vicarious learning may be achieved by collaboration/partnership (Mathews, Reference Mathews2002) such as partnering with incumbents’ suppliers (e.g., Xiaomi had OEM contracts with Apple's largest OEM supplier, Foxconn), and formal education such as taking courses. In this article, we leverage our in-depth understanding of two QSR organizations in China and India to illustrate i) the creative and imitative aspects of business model replication through inter-organizational learning; and ii) the mechanisms of organizational learning that lead to SBMI.

We have summarized in Tables 1 and 2 the relevant studies in the literature.

Table 1. Literature summary on business model innovations in emerging markets and secondary business model innovation

Table 2. Literature summary on creative imitation

METHODS

We used purposeful sampling (Patton, Reference Patton1990: 169) to identify two subject companies that had achieved success through SBMI, and used qualitative theory building techniques for data collection and analysis (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007). Our inferences in this article are drawn primarily from in-depth case studies of two QSR organizations operating in India and China. Each of our subject organizations, Goli Vada Pav Private Limited (GVPPL) of India and Shanghai Dingyu Food Co (SDFC) of China, which operates the QSR chain Jiujiuya, were established in the early years of the 21st century and faced opportunities and challenges unique to emerging economies. The entrepreneurs successfully identified opportunities to launch food businesses, which were hitherto run mainly by informal enterprises, and have since achieved scale in their operations.

Our study is unique as it is based on a vast amount of primary data on the subject organizations; we had access to the founders of the two organizations and conducted detailed recorded interviews with them and with their teams on multiple occasions. In addition, we interviewed other key internal and external stakeholders such as senior managers and investors. We had 15 respondents in the case of GVPPL and 7 in the case of Jiujiuya (see Table 3 for a list of interviewees). The relative imbalance in the respondent numbers in the two cases was made up by the large number of Chinese news articles available on Jiujiuya (depending on the day on which the search was conducted on Chinese search engine Baidu, we recorded between 772 and 940 non-unique news articles and blogs). We shortlisted unique articles based on criteria derived from the Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013) framework. The Chinese shortlisted articles were translated into English and the translations were incorporated into our data. In the Factiva database, we found 84 articles for GVPPL and 6 for Jiujiuya. We also found research articles with references to Jiujiuya in Chinese management journals; we had the relevant sections translated into English.

Table 3. List of interviewees

As a first step, we developed two teaching case studies from our data in 2010. The case development for each of the companies was an iterative process wherein the first draft was prepared and sent to the founders to obtain feedback on factual accuracy, inferential accuracy, and completeness (i.e., that the narrative had not left out important events). The cases were then sent to an international case distribution organization where they underwent peer-review. When we taught these cases to MBA and EMBA students, we invited the founders to come to class and, at the end of the case discussion, interact with the students. The sessions in which the two lead founders participated had each between 60 and 70 experienced students (median age of approximately 28 years in the case of GVPPL and 40 in that of Jiujiuya). The GVPPL founder interacted with three groups of nearly 70 students each. Our students asked the entrepreneurs a number of probing questions regarding their start-up process, their customer profiles, their expansion strategies, human resource issues (both at the outlets and the headquarters), and other key challenges. The in-class interactions and the subsequent one-on-one interviews were video-recorded and provided us with valuable additional information.

We have tracked the companies since 2010, both through personal interactions with the founding teams as well as through media articles that have appeared periodically. In the case of Jiujiuya, the lead founder left the company in 2011 and we have been in touch with his successor, himself a member of the original founding team. The diversity of our data sources – interviews with multiple respondents, presentations by the founders to our students followed by Q&A sessions, media articles as well as research articles – helped us achieve methodological triangulation (Stake, Reference Stake1995: 114), which also mitigated the recall bias of events and actions that had taken place several years previously.

For our data analysis, we identified interview chunks based on the business model framework of Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013) and grouped them in four ‘buckets’: customer identification, customer engagement, value chain, and linkages and monetization. We were looking for elements of the subject company business models that were imitative and creative with respect to those of the international QSR brands. Once we had done this, we went back to our interview and archival data for quotes and chunks to i) separate the creative and imitative elements in the two business models; and ii) understand ‘how’ our subject organizations had acquired the knowledge from the international brands.

Brief Summaries of the Entrepreneurs and Their Ventures

Both the lead entrepreneurs of GVPPL and SDFC are university graduates and come from non-business families. They had worked as paid employees for many years before becoming first generation entrepreneurs. Both had previous entrepreneurial experience and saw growth opportunities in a business that had previously existed primarily in the informal sector in the form of individual street food vendors.

Goli Vada Pav Private Limited (GVPPL)

Venkatesh Iyer, a graduate of the University of Mumbai, co-founded GVPPL in 2004 as a fast food chain to sell the popular Mumbai street snack called ‘vada pav’ under the brand name of Goli Vada Pav. The original vada pav is a deep-fried potato patty that is placed between a sliced bun (similar to a hamburger bun) and served typically with tamarind chutney (spicy sauce). Vada pav was previously sold (and continues to be sold) by street vendors.

In August 2011, the venture capital fund Ventureast invested INR 210 million (approximately US$3.5 million) in GVPPL. In 2014 GVPPL was awarded the Coca Cola Golden Spoon Award under the category of ‘Most Admired Food Service Chain of the Year: QSR Indian Origin’. By March 2019 GVPPL had successfully established 300 outlets, 40 owned and 260 franchised, in 90 cities across 21 Indian states.

Shanghai Dingyu Food Company (SDFC)

Gu Qing, a graduate of the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, established the Shanghai Dingyu Food Company (SDFC) in September 2002 to sell stewed duck neck, a well-known snack from Wuhan, China. The product was registered under the brand name of Jiujiuya. The stewed duck necks had been primarily sold by local street vendors in Wuhan, Hubei province, China. The company had raised a small amount (RMB 500,000) in angel funding in 2003. In 2016, the company received funding of RMB 172.5 million from Golden Oak Investment Holding (Tianjin) and relocated its headquarters from Shanghai to Zhejiang province, which involved moving to a much larger and more modern factory. By April 2019, SDFC had an extensive network of 1,400 retail stores (90% of them run by franchisees) covering more than 20 large and medium size cities in China.

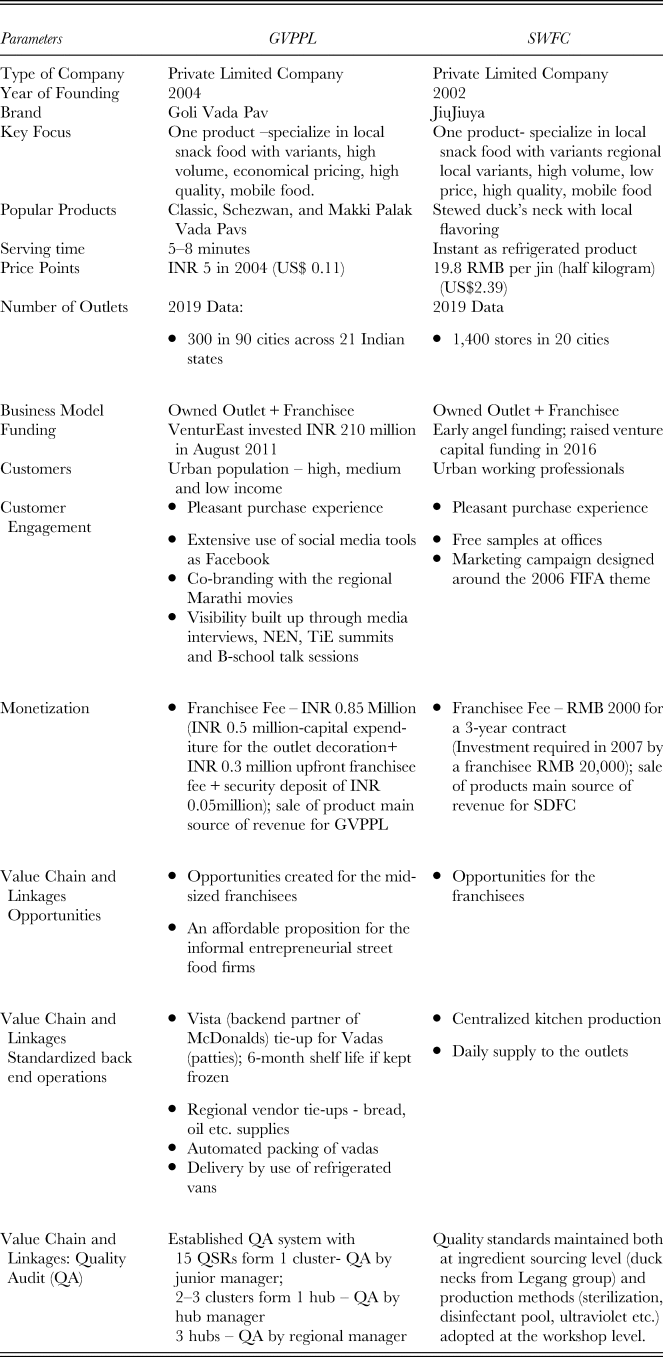

In Table 4, we provide summary data on our two subject companies’ business models.

Table 4. Key features of two business models

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

In this section, we describe the business models of the two organizations along the four dimensions of the Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013) framework. For each dimension, we specify whether it was ideated largely by the entrepreneurs themselves (creative) or learned predominantly from the leading multinational QSR chains (imitative).

Customer Identification (Creative)

As a result of prolonged periods of high economic growth, there has been a shift in food consumption patterns in China and India, with the key drivers being the expanding middle class, urbanization, higher youth spending relative to older age groups, nuclear families, increase in dual-income couples leading to increase in household disposable income, increase in necessity based as well as discretionary eating out, increase in health and hygiene consciousness, etc.

In both GVPPL and SDFC, the founders had the insight that the popular regional street foods could be scaled into national chains. They correctly predicted that their respective regional foods would have national appeal and took the entrepreneurial action of launching their businesses.

GVPPL's first outlets were in the city of Mumbai, where the vada pav as a snack had been born. This meant that the company did not need to spend any resources in educating customers. The customers it targeted were already consumers of the product. It came up with products that were hygienically cooked, accessible, quick to serve and consume (vada pav is considered ‘finger food’, which meant it did not require plates and cutlery, and is therefore mobile food), with traditional flavors, and at competitive and affordable price points. The initial price point was Indian Rupees (INR) 5, which was about US$ 0.11.

When it started opening stores outside the state of Maharashtra, it expanded the market for vada pavs because customers outside Maharashtra also started consuming the product, although with significantly lower frequency. Although the market outside Maharashtra was not accustomed to vada pav, the main ingredients – potatoes and garbanzo bean flour – are widely used in all regional cuisines in India and, therefore, getting people to try the product was not difficult.

Similarly, SDFC was able to offer JiuJiuya's stewed duck neck at a price of CNY 19.8 (US$ 2.39) per half-kg, providing the consumer value-for-money for a quality product. If we look at SDFC in 2002, Gu (the founder) was quick to identify Shanghai as his first target market as he was sure that the product would be a hit in this city, because of its large customer base, large percentage of immigrants from all over China, and high average income. Thus, the customers identified were urban, white collar residents, and his product JiuJiuya fulfilled their need to eat hygienically cooked street food with regional Chinese flavors.

Gu Qing had understood even before he founded his company that stewed duck necks had wide geographic appeal. He learned this in a very ingenious way: when he was working as the regional manager of the Guangdong Robust Group based in Wuhan, he used to attend the national sales conventions of the company. He would take several kilos of stewed duck necks to the conventions, and noted that his colleagues from all over the country relished them. As with the vada pavs, there were very few outlets outside Hubei province (capital city: Wuhan) that sold stewed duck necks (for example, he knew of just one outlet in Shanghai that sold them). With 1,400 outlets all over China by 2019, Jiujiuya expanded the product's reach. Over the years, there emerged other competitors who sold the same product under a different brand.

The commonality that exists in our subject organizations is the ability of the founders to identify the unmet need of their customer – initially, the urban middle-class working populations in Mumbai and Shanghai in search of food options that are healthy, convenient to purchase and quick to eat, affordable, and that are based on local flavors.

As a result of the products chosen (regional snacks), both entrepreneurs identified target consumers that were significantly different from those targeted by the leading international QSR brands in China and India, which initially targeted children and young modern consumers in the two countries. This also led to the price points being much lower than those of the international brands; the prices of GVVPL and SDFC were initially not much different from those of street vendors who sold the same product.

Customer Engagement (Creative and Imitative)

The value proposition of these companies is the standardized customer experience offered across their outlets. Iyer noted,

The stores had an attractive décor with red boards with Goli logo that stood it apart. Our vada pavs being quality product, packed hygienically (as compared to the street vendors) in butter paper, served in no time with a smile and at comparable price point, made all the difference. They were priced at just Re 1 higher than the street vendor product.

Mainly word-of-mouth publicity brought us the business, we also had one Omni Maruti car that used to deliver vadas to our outlets, this car also was painted in a similar color (bright red with Goli logo) as that of the Goli Vada Pav bill boards, this car at times was sent generally to do rounds in these markets thus that was our way of publicity, other than this no additional publicity was done at that point in time. (Venkatesh Iyer, written response to question)

Consumer likes hygiene, consumer likes quality, he can see it. (Venkatesh Iyer, speech to students in 2012, some segments have been translated from Hindi)

Starting in 2007, GVPPL has been engaging with customers through their Facebook account. With their initial success in Mumbai as they expanded to other cities they created city-wise customized Facebook pages which talked about the various events organized by the company in the respective cities. GVPPL also engaged in co-branding activities with regional Marathi language movies for publicity. Iyer actively participated in the National Entrepreneurship Network (NEN) and the The Indus Entrepreneurs (TiE) summits year after year with the purpose of creating awareness about his company's product offerings. At the same time, he found time to actively engage with management students at business schools across the country. He noted,

With low marketing budgets, these forums have proved to be an effective mode both with respect to free publicity as well as a platform to connect with a large audience at a single point of time.

Venkatesh was proactive in giving public interviews both to the print and television media. The GVPPL story was covered multiple times in A-list media such as the Financial Times, Inc India, Economic Times (the business daily with the highest circulation in India), Business Standard, The Hindu, Indian Express, and the Hindustan Times. It was also featured multiple times in leading television channels.

Jiujiuya also offered a standardized product and a standardized customer experience across its outlets. Their products were hygienically made and presented, by virtue of having being prepared in a centralized kitchen. The décor of the stores was also uniform across locations, which helped with branding.

In 2002, the market response to Jiujiuya's first store was very poor, and there was only one customer on the day the store opened. Gu Qing and his team then decided that they had to promote the product in the vicinity of the store.

…. we have been continuing our efforts, including various promotion activities such as free tasting, flyers, and distribution, etc. We also did door-to-door sales in a commercial building specialized in computer products. Immediately our daily turnover rose to 1,000 (CNY) a day. (Gu Qing, interview transcript, 2010, translated from Chinese)

Initially, the company faced a positioning problem:

He (Gu Qing) spent one week in Shanghai to develop the new product ‘marinated duck’, but then ran into the problem of product positioning. Jiujiuya is positioned as a brand for snacks, but marinated duck is cooked food. How to sell it as a snack for leisure time? Inspired by He Boquan (Gu Qing's former boss and later angel investor), Gu Qing studied the business of McDonald's and KFC and came up with the solution. He decided to sell the marinated duck in pieces, so that they could be taken into the office by white collars just like chicken wings sold by western fast food chains. The price would also be much lower when selling by pieces, compared with the fairly high price of RMB 29.8 per duck. (Han, Reference Han2006)

Thus, both the food chains interacted with existing and potential consumers, engaging with them and fulfilling their unmet need of good quality food with traditional flavors at affordable price points and in conveniently accessible locations. In addition to increasing general awareness in the regions where they had shops, the two companies also engaged with customers at a micro level, i.e., at the level of individual outlets. Their marketing campaigns in the initial years were frugal due to their limited resources and yet effective. They did this through the choice of location (high footfall areas), attractive and colorful signage, and distribution of printed publicity material in the neighborhood.

In terms of the standardization of the store appearance and customer experience, our two subject companies drew inspiration from and aspired to emulate the international QSR brands. In their communication strategies with potential customers, however, they had to adopt different strategies because they had to be creative to overcome their resource constraints, resorting to local promotions in the vicinity of the stores and public relations strategies to achieve maximum visibility with minimum investment.

Monetization (Creative)

When GVPPL launched the franchise model, franchisees were required to make an initial investment of INR 0.5 million (US$ 8,300) for setting up the outlet and buying the equipment. Additionally, they were required to pay a one-time franchisee fee of INR 0.3 million (US$ 5,000) and a security deposit of INR 0.05 million (US$ 830) for future purchases. GVPPL provided the franchisee with the main ingredients such as the vadas (patties) and the sauces. The supplies of other ingredients such as pav (bun), oil, cheese etc., were provided by regional local vendors who were partners of GVPPL. The franchisees earned revenues and profits from the consumers by selling the vada pavs whereas GVPPL earned its revenues from the franchisee fee and the sale of the products to the franchisees. SDFC in China also had a similar arrangement when it first launched the franchise model. The total initial investment by the franchisee was about CNY 45,000 (US$5,440 based on the exchange rate at the end of year 2002) inclusive of the franchisee fee and the operating costs. SDFC supplied the franchisees the products on a daily basis and gave them a rebate of 1% of purchases for unsold product that had to be thrown away. On average each franchisee was able to earn a profit of CNY 5,000 yuan per month, which was an attractive alternative to factory employment for migrant workers from poorer Chinese provinces.

According to our estimations (both companies are privately owned and were unwilling to share their financial statements with us), both companies make a gross margin of between 25% and 30% on sales to franchisees. The operating margins from owned outlets are higher, as GVPPL and SDFC get the retail price of the products, but the outlet operating costs have to be borne by the companies.

In terms of monetization, our subject companies followed the template of the leading QSR brands in terms of appointing franchisees, requiring them to make investments and coming up with an economic model that was attractive for the franchisees on the one hand and allowed them (our subject companies) to capture a part of the value created for themselves. However, both the investment and the monthly operating expenses for each store were very modest in comparison to those of the leading international QSR brands, due to the much lower price points and the much smaller store sizes.

Value Chain and Linkages (Imitative)

Retail outlets: The two organizations GVPPL and SWFC started by specializing in just one vertical, the local snack food. These companies created new opportunities for a second set of stakeholders – the franchisees. The initial investment for setting up a GVPPL franchisee was INR 0.85 million. In the case of SDFC, this cost was CNY 45,000. In return, these companies assured the franchisee of a tried and tested business model, which was based on their own stores. They added value to the franchisee by offering products, through their standardized mass production processes, that had wide appeal.

Supply chain: GVPPL was able to reach an agreement with Vista Foods, McDonalds’ contract manufacturer for patties and other products, to produce the potato patties for it. This meant that GVPPL was able to immediately access Vista's strong back-end processes and manufacturing capacity, which ensured production of 75,000 vadas (patties) in just 60 minutes. They are all hygienically packed and can be refrigerated at the franchisee outlet with a shelf life of 180 days from the date of production. They are transported in refrigerated vans operated by Jeena & Co from Vista's plant in Mumbai to all the regional hubs for further distribution to the franchisee. GVPPL has agreements with the locally identified vendors of every region for the supplies of pavs (bread), oil, etc. to the franchisee outlets. In this manner GVPPL has been in control of the quality and regular supplies to their franchisees. GVPPL promises strong support to the franchisee with the initial setting up activities and training in standard operating procedures to run the franchise successfully.

SDFC in China sources the necks of the white Pekin (a specific breed of duck) from a supplier in Shandong Province. The supplier adopts European standards with regards to slicing, sorting, disinfecting, freezing and packaging processes. This supply is characterized by freshness, large and even size, fleshiness, and low moisture content, reducing the probability of secondary contamination. SDFC adopts modern techniques for quality processing at their new 40,000 square feet central facility; they also ensure that each employee holds a health certificate, changes into a sterile one-piece uniform, puts on work boots and a cap, and finally walks through a pool of disinfectant liquid before entering the work areas. The employee uniforms are sterilized with ultraviolet light around the clock and replaced every day. The standards followed from high quality ingredient sourcing to the final production contribute to high quality levels and a standardized product capable of generating value for their franchisee (in terms of sales revenues) and in turn help build strong franchisee relationships.

When it comes to value chain and linkages, we see perhaps the greatest similarity between our subject organizations and the international QSR brands, to the point that GVVPL even partnered with the contract manufacturer of McDonalds. See Table 4 for an overview of the business models of the two companies.

The point to be noted here is that these companies, with their low cost business models and reasonable franchisee fees, offered an attractive proposition for local entrepreneurs. Indeed, both GVPPL and SDFC showed an inclination to partner with franchisees who typically preferred to run the operations themselves rather than those who acted as investors and hired employees to run the outlets; they found that owner operated outlets were more focused on following the quality norms and thus contributed to maintaining and building brands’ image.

The impressive growth of the two organizations studied does not mean that they did not face challenges. Competition from other fast food chains, political interference, undisciplined franchisees, dissatisfied franchisees (who were unhappy with the margins they were able to make or with the support they were getting from the franchisor), and rent increases that the landlords wanted to impose on the outlets, were some of the problems they had faced and continue to face.

DISCUSSION

Imitative and Creative Aspects of GVPPL and SDFC with Respect to International QSR Chains

Creative

There were three creative aspects of GVPPL and SDFC with respect to the international QSR chains that served as their points of reference. First, the products that they chose to offer to the market were regional ethnic foods that were originally popular in one specific region of their respective countries (the city of Mumbai in India and the city of Wuhan in China). Second, the target customers for GVPPL and SDFC were older and more traditional than those of McDonalds and KFC. Initially children constituted an important, if not the main, target segment for McDonalds and KFC in China and India. Further, in the 1980s and 1990s, eating in the outlets of these international brands was considered a sign of modernity (Yan, Reference Yan2006), and therefore, it was the younger and more modern consumers who frequented these outlets. Third, the price points at which GVVPL and SDFC offered their products to their respective markets were only very slightly more expensive than the offerings of single outlet vendors, and significantly below the prices of the international QSR brands.

Imitative

There are many areas in which the two entrepreneurs made concerted efforts to copy the practices of the international QSR brands. These were mainly operational functions (both front end and back end), such as choice of store locations, standardized store formats and decorations, staffing (including onboarding of new employees and franchisees), store operations (including food preparation and interactions with customers), and manufacturing and supply chain management.

If we were to relate the imitative and creative aspects our two subject organizations to the Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013) framework, then clearly the customer identification (target segments, price points) and monetization (investment required, both at the company level and the franchisee level, and the operating expenses) aspects were quite different from those of the international QSR brands that they used as benchmarks. Customer engagement was similar in one respect, in terms of their wanting to offer their customers both a standardized product and a standardized store level experience. Customer engagement was different insofar as our subject companies had to be mindful of their resource constraints when they made decisions on how to communicate with existing and prospective customers. The most imitative aspect of the business models was clearly the value chain and linkages (broadly speaking, the operational aspect).

Key Learning Mechanisms for Secondary Business Model Innovation

Contextual learning

Rae (Reference Rae2005) proposed that entrepreneurial learning is made up of three broad themes: personal and social emergence, negotiated enterprise, and contextual learning. Contextual learning in turn consists of opportunity recognition through cultural participation, learning through immersion within the industry, and practical theories of entrepreneurial action (Rae, Reference Rae2005: 328–329). We find that the creative (i.e., non-imitative) aspects of the business model were mainly attributable to contextual learning.

Opportunity recognition through cultural immersion. Clearly, both entrepreneurial were deeply rooted in their cultural contexts and understood the food cultures of their respective countries. They also observed the changing behavior patterns of consumers, who clearly were becoming increasingly sensitized to hygiene, food safety and convenience. Their cultural immersion and astuteness in detecting changes in consumer behavior played a key role in the opportunity recognition process.

Learning from the industry. The learning from deeply engaging with the industry was an ongoing process for both entrepreneurs. Understanding the recipes, the ingredients and the quantities to be used, the taste that had to be achieved to be achieved to draw the customers into the stores, the sources of supply of raw materials, the availability of talent (both for own stores and franchised stores), and the availability of infrastructure such as cold chain for frozen products, were some of the learnings that the entrepreneurs acquired with the passage of time in the industry.

Practical theories of entrepreneurial action. Learning by doing (Anzai & Simon, Reference Anzai and Simon1979; Arrow, Reference Arrow1962) has long been acknowledged as an important form of learning. Not surprisingly, it is an important source of entrepreneurial learning (Cope & Watts, Reference Cope and Watts2000). As they acted on what they believed would be attractive business opportunities, they learnt in a number of ways, often going through frustration and pain. For example, although Venky Iyer had read about wastage and pilferage in the food industry, he saw the full import of these problems only when he faced them on a large scale. Similarly, Gu Qing was surprised that only one customer showed up on the first day of their first store opening. These and other similar problems led them on a path of reflection, discussion with members of their network and a number of initiatives designed to overcome them.

Vicarious learning

The inspiration. Previous studies have highlighted the role of inspiration in vicarious learning in diverse fields such as business (Ghoshal & Westney, Reference Ghoshal and Westney1991, learning from competitors) and education (Steenekamp, Van der Merwe, & Mehmedova, Reference Steenekamp, van der Merwe and Mehmedova2018, learning from inspirational teachers). We find that inspiration from visibly successful organizations can spur individuals into entrepreneurial action.

Iyer drew inspiration from McDonalds to set up GVPPL. His neighbor, who worked for Kelloggs in India, complained that they were finding it difficult to get Indians to change their food habits, and this planted the first seed in Iyer's mind for building a business around ethnic food. He described the moment he decided to build a business around vada pav.

I stay in Mumbai and near VT station (Victoria Terminus railway station) there is McDonalds, a big M on a 40-foot banner and a big burger photograph, and below him there was a ‘haath gadi wala’ or ‘thela wala’ (handcart pusher)…. Normally in every corner in Mumbai there is a ‘thela wala’, with a ‘chappan tikli baniyan’, fifty holes in the baniyan (vest) and a ‘lehenga’ (like a skirt) and in a shabby condition he fries the ‘batata vada’ (potato patty). I also picked up a vada pav like the others and when I looked at it ….. that (McDonalds burger) is anything between buns, this (vada pav) is anything between ‘pav’ (bread), that is mayonnaise this is chutney, that is non-spicy this is spicy. (From presentation to MBA students in July 2012, some segments have been translated from Hindi)

Jiujiuya also drew inspiration from established QSR chains, such as international brands McDonalds and KFC and also domestic packaged snack food brand Shanghai Laiyifen, which had already started to grow in 2002 and by 2018 had grown to 2,700 outlets.

At the very beginning, Gu wanted to get into the national chain. At that time, there was no such a brand in the Chinese prepared food industry, we wanted to be the first, but it was a pity that we didn't have a thorough understanding of how to operate a national chain of outlets. (Pan Yixuan, CEO in 2019 and member of original founding team)

In the early days, we planned to expand our business by following Laiyifen's model. More specifically, in the initial stage, to open company-owned outlets in Shanghai, and when we built certain brand awareness, to open franchised outlets across the country. (Li Jiong, Director of Supply Chain Management and member of the original founding team)

Observation and study. Observation is one of the main mechanisms of vicarious learning (Chi, Roy, & Hausman, Reference Chi, Roy and Hausmann2008; Denrell, Reference Denrell2003; Terlaak & Gong, Reference Terlaak and Gong2008), although whether the inferences drawn from observation are accurate or not is an open question. Denrell (Reference Denrell2003) argues that focal firms observe successful organizations more than unsuccessful ones, which by virtue of not surviving are not subject to observation. Therefore, there is a selection bias when observers draw inferences about organizational practices from successful organizations. In the case of both GVPPL and SDFC, since the learning from observation was limited to store appearance, consistency of branding etc., which represented no causal ambiguity (Lippmann & Rumelt, Reference Lippmann and Rumelt1982), there was limited room for erroneous inferences to be drawn.

SDFC took several measures to benchmark itself against the established international QSR chains such as McDonalds and KFC. According to Han (Reference Han2006),

Jiujiuya has opened neat and tidy stores nationwide with the same logo. Gu Qing explained that visual identity is the biggest feature of Jiujiuya in the eyes of consumers. He hoped that consumers could recognize the high quality of Jiujiuya upon seeing its brand. McDonald's restaurants across the world also maintain the same visual identity. (Translated from Chinese)

Pan Yuxian listed the ways in which Jiujiuya learnt from both McDonalds and KFC – ‘(We) learned the method of location choosing of physical stores from McDonald's and KFC, and referred to the store location of these brands as an important factor for our store determination’ (written response to question).

Chen (Reference Chen2010) also pointed out other ways in which Gu Qing and the General Manager of Jiujiuya He Hongyuan absorbed learning from the leading QSR brands.

As newcomers to both the duck neck business and the chain business, Gu Qing and He Hongyuan had to figure out how to manage the chain system, build the management structure, and avoid diseconomies of scale. He Hongyuan stressed the necessity of staying humble as they drew experience from other chain enterprises such as KFC, McDonald's and Real Kungfu. ‘We would learn from the books, online articles and newspaper clippings about McDonald's to improve ourselves. Lectures are also helpful. For example, during a lecture by a visiting professor at Tsinghua University, who was the professor of McDonald's Hamburger University and compiler of McDonald's handbook for Greater China, I was enlightened on many issues that had perplexed me for many years’. (Translated from Chinese)

Pan Yuxian added – ‘Learned from the McDonald's and KFC store operation and management manuals, and adjusted the applicable parts of these manuals to make Jiujiuya's store management manual’ (written response to question).

Hiring employees from international QSR brands. One of the main mechanisms for inter-organizational knowledge spillovers is talent mobility from one organization to another (Spender, Reference Spender1996; Spender & Grant, Reference Spender and Grant1996). Knowledge acquisition through the attraction of talent is a major source of firm competitive advantage (Whelan, Collings, & Donnellan, Reference Whelan, Collings and Donnellan2010). We see this phenomenon clearly in our two subject companies.

Pan Yuxian – ‘Priority was given to recruiting managers with experience in these brands such as McDonald's and KFC’ (written response to question).

Venky Iyer – ‘The first thing we did was, went ahead and got people from McDonalds’ (interview response). He added that the primary function for which the staff from McDonalds was hired was in operations, to achieve operational excellence. They also hired employees from consumer goods brands such as Unilever and ITC (an Indian brand) for franchisee management, as these brands were accustomed to working with retailers.

Partnering with vendors of international QSR brand. Sheth and Sharma (Reference Sheth and Sharma1997) pointed out that one of the main sources of competitive advantage for a firm lay in the nature of its relationships with its suppliers. Araujo, Dubois, and Gadde (Reference Araujo, Dubois and Gadde1999) identified a number of ways in which buyers interface with their suppliers. One of these interfaces involves the supplier customizing the product for the buyer and using its unique resources and capabilities to bring certain functional benefits to the buyer that the latter could not generate by itself.

Iyer subcontracted the production of the vada pavs to Vista Foods, McDonalds's backend partner in India. Through this relationship, GVPPL was able to get access to an HACCP certified production facility (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point system for minimizing food safety hazards), with products that had a shelf life of six months, with cold-chain logistics and with traceability of each patty (to a specific production shift, to a specific production supervisor and to a specific transport van). This gave Iyer and his team complete peace of mind about backend operations and freed them up to concentrate on the front end. Asked why Vista Foods agreed to partner with GVPPL, a very small company at that time, Iyer was philosophical:

We are scientific minded people. We read science, we do business studies, we do MBA. But there is a world beyond all this, called destiny, called meaningful coincidences. ….. But one of the most important thing is that they saw a passion, they saw a 1970 Mac being started in India ….. and there was also maybe a beautiful thing, which I understood was spare capacity model ….. there is a huge plant, 60% is utilized 40% is vacant, I went and sat there. (From presentation to MBA students in July 2012, some parts have been translated from Hindi)

To summarize, the two entrepreneurs’ offerings were creative and deeply rooted in local culinary customs, which meant that their target segments were very different from those of the international QSR brands, as were the price points at which they sold their offerings. However, their aspiration was to operate their businesses along the lines of McDonalds and KFC in terms of visual image, store appearance, and standardization of product and customer experience. This required them to organize their operations very similarly to the international QSR brands. Thus, the entrepreneurs benefited from both contextual learning (which influenced the creative aspects of their business models) as well as vicarious learning (which impacted the imitative aspects).

Our findings on the three mechanisms of contextual learning and four mechanisms of vicarious learning our subject companies used to formulate and implement their business models are consistent with the extant literature. We present a theoretical framework to capture the process of secondary business model innovation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A theoretical framework for secondary business model innovation (SBMI)

CONTRIBUTIONS

Our key insight is that SBMI is one of the two main mechanisms through which developed country business models are replicated in ETEs (the other being replication by the developed country organizations that originally pioneered the business models through their entry into ETEs). We study how business models are partly based on entrepreneurs’ creativity, which comes from their rootedness in and responsiveness to their contexts, and partly on their replication of reference organizations’ routines. We situate SBMI within the creative imitation literature stream (also referred to as imitative innovation), because it has both imitative as well as creative elements, and propose that there are two types of learning – contextual and vicarious – in the process of ideation and execution.

We make a contribution to the business model literature by further developing the concept of SBMI first coined by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010). We do this by specifying that it has both creative and imitative aspects and that there are two different forms of learning involved: contextual and vicarious. We also contribute to the business model literature by going deeper into the four elements of business models – customer identification, customer engagement, monetization and value chain, and linkages – that Baden-Fuller and Mangematin (Reference Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2013) claim are robust to changing time and context (such as industry). Our study contributes the insight that there is variance in terms of the degree to which each of these four elements is susceptible to innovation (or creativity). Our study found that when developed country business models serve as inspirations for developing country entrepreneurs, then typically there is creativity required on the part of the entrepreneurs in how they identify customers and how they monetize the business models. Both the organizations we studied bear testament to the fact that it is possible to scale such ventures, provided individual cognition to generate new knowledge is used effectively. Whether it was about identification of the food category to be offered or the target customer, optimization of costs by use of free social media promotional strategies, value pricing the product to suit the target customer wallets, or structuring the franchisee agreement to ensure a win-win partnership with franchisees, the entrepreneurs drew their inferences largely from the local business environment. This is because the key drivers of these two elements are the local contexts in which the entrepreneurs are embedded. On the other hand, customer engagement has both creative parts, which have to do with understanding customers deeply and interacting with them in culturally appropriate ways, and imitative parts, which have to do with the standardization of the customer experience across locations. Finally, the two entrepreneurs held only images of the real systems (the international QSR business models) when imitating the venture value chain and linkages. However, it was their individual thinking processes that helped them scan the environment for opportunities (for example: GVPPL's tie-up with Vista Foods for standardized mass production) to generate business value for themselves and their stakeholder (suppliers, franchisees, and customers). The value chain and linkages element of the business model is based more on global best practices, where the degree of imitation is high.

We also make a number of contributions to the creative imitation literature. First, previous studies of creative imitation have been mainly focused on products and services (e.g., Drucker, Reference Drucker1985; Kim, Reference Kim1997; Levitt, Reference Levitt1966; Schnaars, Reference Schnaars1994; Shenkar, Reference Shenkar2010), and less attention has been paid to date to applying this construct to business model innovation (see Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kwon, Lee and Park2016, for a notable exception). Although Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Kwon, Lee and Park2016) did discuss creative imitation as a catch-up strategy in the smartphone industry by illustrating the two cases of Apple and Xiaomi, where the latter was a case of creative imitation of a developed country organization by an emerging market organization, the focus of their study was not to explore the mechanisms through which creative imitation of business models takes place. This article not only extends the creative imitation construct to business model innovation through inter-organizational learning, but also investigates the mechanisms that entrepreneurs leverage to creatively imitate business models, thus achieving SBMI.

Second, as Johansson and Lindberg (Reference Johansson and Lindberg2011) point out, the vast literature on innovation has traditionally emphasized creativity but not replication of routines, and while the much smaller body of work on creative imitation has addressed this shortcoming, we show that the creative and the imitative elements are brought together contemporaneously in SBMI rather than sequentially, which has been the finding in studies of latecomer firms from emerging economies (Ray, Ray, & Kumar, Reference Ray, Ray and Kumar2017; see also Si, Wang, & Welch, Reference Si, Wang and Welch2018, for a review of the literature). Third, as Nani (Reference Nani2016) has noted, the vast majority of imitation studies have focused on Western countries and on imitations in technology intensive contexts. Our study looks at creative imitation to achieve SBMI in two ETEs and in a very traditional sector – food – in which technology did not play a dominant role. Finally, we show the mechanisms – contextual and vicarious learning – that lead to creative imitation.

Limitations and Future Research Implications

Our study has the obvious limitation that is characteristic of any small sample, qualitative study: generalizability. We acknowledge this shortcoming, and encourage other researchers to replicate similar studies in these and other emerging economies in order to gain a deeper understanding of SBMIs, which is a widespread phenomenon in ETEs. Studies could be conducted on SBMIs in budget hotel chains, pharmacy chains, kidney dialysis chains, ride hailing platforms, to name just a few, to understand whether the SBMI process is different from the one we have outlined and whether the underlying learning mechanisms are different. There is one important question our study has raised but not answered: all business models are likely to have both creative as well as imitative aspects. At what mix of creative and imitative aspects does a business model become an SMBI? This is a question worth exploring, as we are sure that there are business models at both ends of the spectrum, i.e., predominantly creative and predominantly imitative.