Introduction

The desire to understand and order colonized lands dominated a large part of British Imperial policy. This is especially prominent in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, where considerable energy was invested in surveying and registering land. Under the orders of Lord Kitchener, Edgar Bonham Carter started conducting detailed land surveys. Following the victory at Omdurman (2 Sept 1898), the Condominium Government was tasked with ordering a vast area of land through the setting up of a legal system, drafting laws and creating new infrastructure. In particular, the government was concerned with changing the configuration of land ownership and acquisition, a task that ultimately proved impossible (Allen Reference Allen2017). This was part of a larger strategy of what Cohn has termed investigative modalities, wherein the powers decided what type of knowledge was needed and how it should be ordered, classified and transformed (Cohn Reference Cohn1996). This endeavour also included archaeology. At its core, it relied on the idea of knowing the native and paternalistic traditions. Less explored, particularly in the Sudan, is the relationship between these policies and archaeology and the resulting impact. A key outcome was the marginalization of archaeology beyond the Sixth Cataract, and Henry Wellcome's attempt overturn this trend.

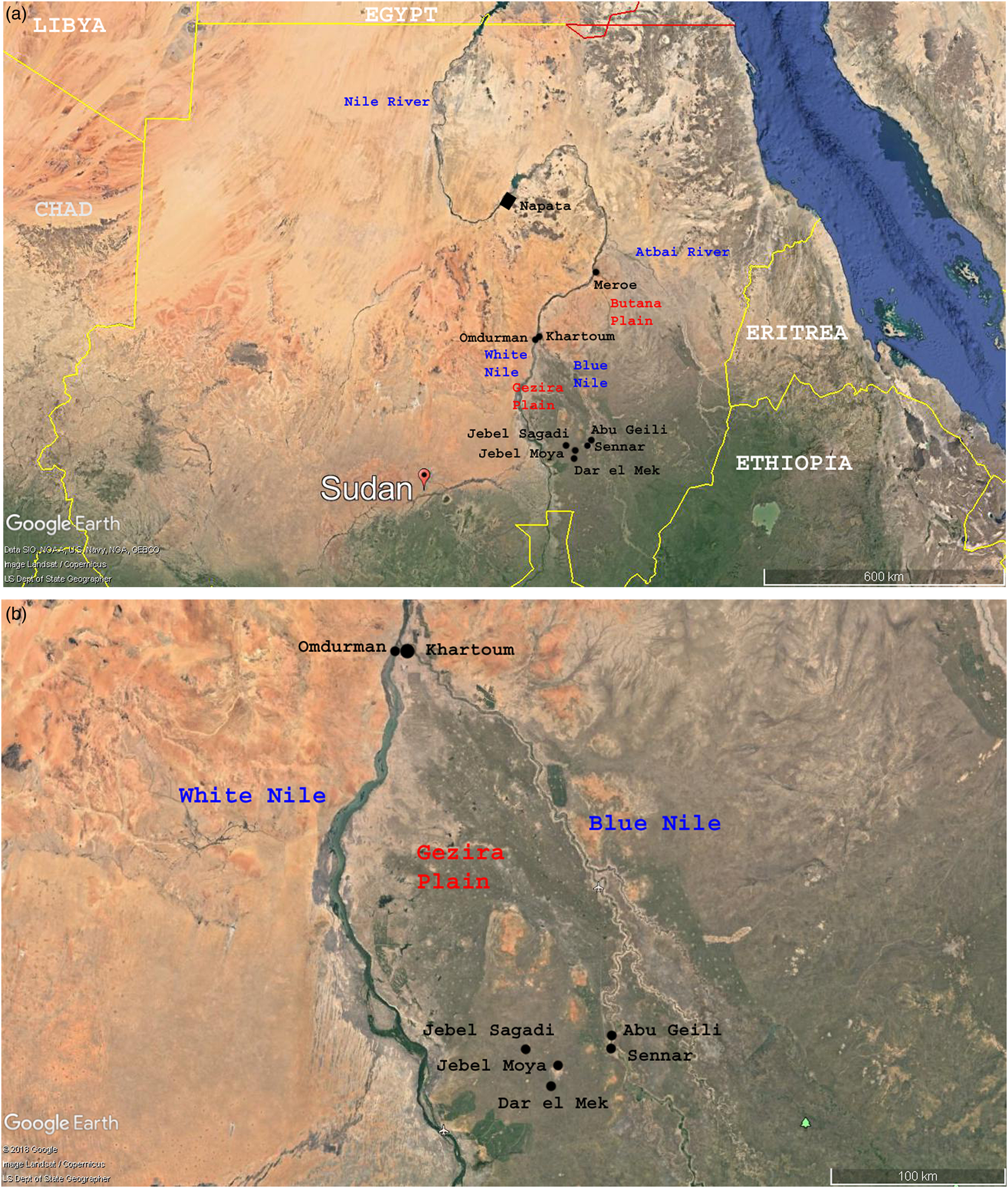

The archaeology of the land around the first five Nile cataracts is well-established in academic enquiry. The lower reaches of the Nile River (modern Egypt) have been extensively explored, as has the archaeology of Nubia, which lies between the first five cataracts. Gaps remain in the areas between the Fourth and Fifth cataracts, although the Meroitic heartland (between the Fifth and Sixth) cataracts has been well-explored. Beyond Egypt and Nubia's incursions into (modern) Sudan, however, the situation is more complex. The area upstream (south) of the Sixth Cataract remains under-explored and it was only from the 1990s onwards that fieldwork really expanded beyond this area (Figure 1a–b). At present, south-central and southern Sudan (as distinct from modern South Sudan) remain at the fringes of enquiry. This is not to say that the inhabitants in this region are unaware of their past. Rather, it is a reflection of western-dominated historical trajectories. A re-consideration of this complex scenario reveals the impact of Henry Wellcome's archaeological interests, combined with the influence of the British colonial administration, and a severe lack of indigenous voices.

Figure 1. (a) map of Sudan, showing the sites under discussion, (b) map of the Gezira plain. (Source map: Google Earth.)

Below the Sixth Cataract

The area below the Sixth Cataract did not capture the imagination of many travellers and its archaeology was first communicated to audiences outside of Africa by Henry Wellcome and his excavations at Jebel Moya (1911–14). After the First World War, Addison investigated some graves at Sennar in 1921 and 1925, and then the area faded from memory (Addison Reference Addison1950). Apart from Randi Haaland's excavation at Rabak in the early Eighties (Haaland Reference Haaland1984; Reference Haaland1987), sporadic but highly valuable research only resumed from the Nineties with Welsby's (Reference Welsby2002) exploration of medieval kingdoms, surveys by Eisa (Reference Eisa1999; Reference Eisa and Khabir2006) and excavations by Usai and others (Usai and Salvatori Reference Usai and Salvatori2006; Usai et al. Reference Usai, Salvatori, Jakob and David2014). It was only in 2017 that excavations resumed at Jebel Moya, the site chosen by Henry Wellcome for his main project. Wellcome had also explored Abu Geili and Sagadi, with the aim of expanding his work across the region. This did not come to fruition and Wellcome's role in archaeology has also faded from memory. Known for his advances in pharmaceuticals, his philanthropy, commitment to medicine and his passion for collecting, Wellcome's archaeological endeavours have been treated as peripheral. As recently as 2017 the site of Jebel Moya has been described as archaeologically unexceptional and valuable only in terms of providing native labour, whereas accounts on Wellcome's penchant for collecting tend to view his excavations as a philanthropic enterprise (Launer Reference Launer2017; Larson Reference Larson2009).

Wellcome's activities were as follows. The site of Abu Geili is about 30 km east of Jebel Moya. Excavated by Wellcome and O.G.S. Crawford, the cemetery was dated to the Funj Sultanate and the village to 200 BC–600 AD (Crawford and Addison, Reference Crawford and Addison1951). AMS dating of charred sorghum grains and spikelets in the UCL Institute of Archaeology's collections to 1790 +/- 40 bp (BETA 194245), calibrated to AD 127–344 (OxCal Intcal13, Sigma 2 (95.4%) confirm the village dates (Fuller Reference Fuller, Stevens, Nixon, Murray and Fuller2014). The graves, however, require further investigation. Brass has noted some overlap in the pottery with Jebel Moya (Brass Reference Brass2016). Jebel Sagadi lies about 20 km north-west of Jebel Moya. It was excavated in 1913 by Duncan MacKenzie at the request of Henry Wellcome. He uncovered a stone wall enclosure inside which there was a red mud brick structure. The site of Dar el Mek, located to the south-east of the Jebel Moya massif, was excavated in 1913. There are remains of terrace walls, huts and houses and the published information is incomplete (Crawford and Addison, Reference Crawford and Addison1951).

By far, the most widely excavated and documented remains the site of Jebel Moya. It is about 10ha in size (Figure 2). The southern wall of the valley is bounded by gentle granite hills, rising steeply to the east and west. To the north, the hills close in towards each other, leaving a gap which forms a sloping accessible gateway to the valley from the plain. From here, there is a view of the Gezira plain and the present village of Jebel Moya. Enclosed between the two branches of the White and Blue Nile, the Gezira plain is currently cultivated. The most visible feature at this multi-period site is the House of the Boulders, built by Henry Wellcome and used as a sort of excavation headquarters. The earliest deposits currently date to c. 5000 BC. To date, 3135 human burials have been excavated by Wellcome and 5 human burials over the course of the 2017 and 2019 seasons; more skeletal remains are visible protruding from the modern ground surface. The site was in use until two thousand years ago, although chronologies are likely to change based on ongoing fieldwork.

Figure 2. View of Jebel Moya from the northeast slope. (Photo: Isabelle Vella Gregory.)

Wellcome's endeavours had limited impact on the archaeological future of the region: the reasons include the primacy placed on Egyptian, Nubian and Meroitic archaeology; the administration's preference for anthropology; and the far-reaching impact of colonial policies as defined by the Condominium Government. Similarly, the argument that Jebel Moya is on the fringes of ‘civilizations’ is an academic construct tethered by a complex socio-political history. The Gezira plain's slide into archaeological oblivion is linked with the concept of ‘civilizations’, particularly as defined by the colonial administrators who saw none in this area.

Sudanese studies and African archaeology

The trajectory of African archaeology is different to that in Europe and North America. There remains a stark distinction between Northern and sub-Saharan Africa and while this gap has closed considerably in recent years, the entire country of Egypt and its archaeology remains largely a separate entity in archaeological inquiry. Furthermore, centuries of colonial rule (British, French, Belgian) on the African continent has resulted in archaeological and anthropological narratives written by the colonists and for a western audience. The independence of individual countries was a long process, and equally long and varied was the emergence of countries writing their own narratives and taking charge of their heritage.

Colonial powers sent their missions and brought back artefacts. Prehistory, particularly the Palaeolithic, was seen through the lens of the European (especially French) Palaeolithic. The archaeological record, however, showed a very different picture. While terminology changed, attitudes lasted much longer. Thus, rock art was seen as the result of diffusion from Europe and extant hunter-gatherer groups became a living laboratory for ‘primitive’ societies. The development of archaeology in Africa is very much a colonial endeavour. Many archaeological undertakings were conducted by employees of the colonial powers: civil servants, military personnel, teachers, missionaries and other assorted members of a large and complex administration. Colonial powers were concerned with mapping and documenting their territories and these expeditions resulted in some of the first archaeological surveys.

While the trajectory of each country is different, the colonial period led to a number of trained professionals. In South Africa, for example, the Stone Age was re-arranged, standardised and given a new nomenclature by the Cambridge-trained South African archaeologist Charles Goodwin. While the world had changed considerably in the aftermath of the Great War, views on the status of Africa and Africans had a somewhat more measured trajectory. Goodwin, for example, was beaten in the publishing race by his Cambridge mentor Myles Burkitt. This is not to say that Africans were silent on the matter, in particular South Africans like Steve Biko had plenty to say about the colonial agenda of denying people their history (for a full discussion see Shepherd Reference Shepherd2002).

The situation in the Sudan is more complex. Officially, the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan was not a British colony but a Condominium. In practice, it functioned like a colony. The Condominium government did not have any plans to bring in European settlers. Nevertheless, it set up an entire legal system and sought to show the Foreign Office and potential investors that the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan could be a great example of infrastructure and economic growth (Allen Reference Allen2017). The Condominium government had long documented the ‘quirks’ and ‘character’ of the Sudan and Wellcome's expedition is set against this background. The journal Sudan Notes and Records (SNR), established in 1918, became a showcase for British officials and their associates to publish their views on Sudanese habits, customs and archaeology (and other topics). In many ways, this singling out of the Sudan is reflective of the country's status as not quite African and not quite Arab. SNR is very much reflective of the British attitude towards Egypt and the Sudan. As Hamad notes, the journal was an encyclopedia of information of the country, with a tacit role in shaping British policy. The journal promoted Sudanese nationalism (with a view to politically separating Sudan from Egypt) (Hamad Reference Hamad1995). While there is a strong focus on anthropology, SNR sought to reconsider the history of the whole Nile Valley. The focus was really on the Egyptian-Nubian question, as noted in George Reisner's four-part paper on the ancient history of the Sudan (Reisner Reference Reisner1918a/Reference Reisnerb/Reference Reisnerc; Reference Reisner1919). Reisner was a noted Egyptologist who worked briefly at Jebel Moya and excavated Kerma and other sites (Crowfoot Reference Crowfoot1943). While Reisner's interests were archaeological, particularly the development of rigorous excavation methods, the SNR saw an opportunity to foster the concept of Sudanese nationalism as opposed to Egyptian sovereignty. These efforts were redoubled after the World War II, with a focus on the Funj Kingdom and early Sudanese history (Hamad Reference Hamad1995).

The SNR epitomizes the culmination of investigative modalities and the administration's difficulties with the Sudan. In particular, the desire to avoid another Mahdist revolt had repercussions beyond the corridors of politics. There is a distinct focus away from history, archaeology or anthropology related to Islam. The emphasis is very much on Egypt and the presumed (debated) Nubian origin of the Funj. Sudan's uncertain status very much outlived the colonial period. As Sharkey et al. (Reference Sharkey, Vezzadini and Seri-Hersch2015, 3) note, Sudan ‘not only fell on the margins, but between the cracks’. Arguing for a rethinking of Sudan studies, they ask scholars to feature the agency of non-elite actors and examine societies at the grassroots. While their special issue of the Canadian Journal of African Studies does not include archaeology, the point stands. Studying societies as diverse groups of individuals, focusing on daily practice and modes of action is at the heart of archaeology.

Henry Wellcome's expedition to Jebel Moya

Early visits to the Sudan

Wellcome's first foray into the Sudan was not archaeological in nature. He was one of the first civilians to visit the Sudan after Lord Kitchener overthrew the Dervish rule in 1898. His first studies concerned the welfare of people, famine, pestilence and disease. Wellcome was deeply affected by what he saw and set up the Tropical Research Laboratories (WTRL) (Kirk Reference Kirk1956). The Jebel Moya excavations enabled him to combine welfare with his passion for archaeology. Prior to this, Wellcome already had a vision of ‘Africa’ as a land of medical possibilities. In 1865 he acquired a supply of Strophantus pods, discovered by Sir Thomas Frazer, and he eventually developed strophantine, a drug used to treat heart disease. He also joined the American May French Sheldon's ‘African’ salon in London and developed a keen interest in the scramble for Africa, the process by which the African continent was invaded, occupied, divided and colonized by European powers (1881–1914). Thus, when Kitchener appealed for money to build Gordon College in Khartoum after the conquest, Wellcome obliged. Wellcome's name was not entirely unknown to Kitchener, who had read his book on the Metlakatla people in Alaska (James Reference James and Simpson2008).

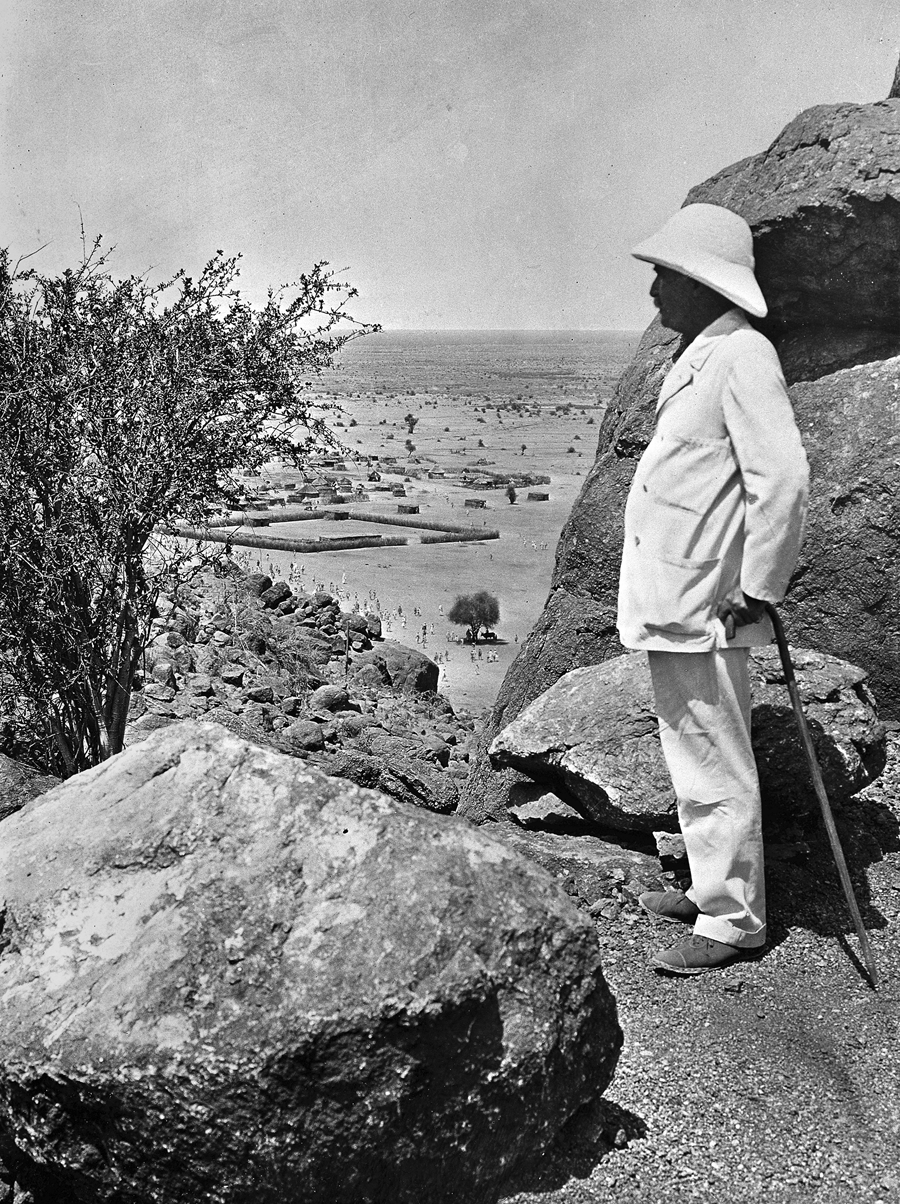

The WTRL became the primary institution for all scientific research. Andrew Balfour and, later, Albert Chalmers established the relevance of research to practice. Reconciling the administration's investigative modalities with scientific research was not easy and the process required constant re-negotiation. Nevertheless, the laboratories were a success. Wellcome's generosity has been linked to his general benevolence but, as Heather Bell notes, Wellcome whole-heartedly believed in the imperial project and the benefits of lucrative commercial medicine (Bell Reference Bell1999). By 1901, he was already a commercially and socially successful man. He believed that his laboratories were key to making the colonial enterprise profitable (sensu Chamberlain's constructive imperialism) and his portable medicine chests for expeditions were one part of his grand scheme. Wellcome modelled the Khartoum laboratory after the ones in London, with the idea of producing marketable drugs and further strengthening the link between science and commercial enterprise, an endeavour that was still viewed with suspicion by sectors of the British medical establishment (Bell Reference Bell1999). The WTRL published articles in journals in which Burroughs & Wellcome Co advertised its wares and the subsequent lavish reports, which Wellcome distributed widely, established his credentials as a benevolent imperial philanthropist just as his company was expanding. In a rare press interview, Wellcome baldly declared that ‘All central Africa is going to be made perfectly habitable for the white man. Its agricultural, industrial, and commercial resources will become available. The Niles and their tributaries will teem with the commerce of a numerous and happy people.’Footnote 1 This vision extended to the archaeology of the entire Sudan, although Jebel Moya would be his only excavation in Africa (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Henry Wellcome at Jebel Moya. (Photo: Wellcome Collection.)

Welfare, employment and indenture

Aside from archaeology, one of Henry Wellcome's interests was welfare, as defined by late Victorian and Edwardian standards. Wellcome was involved in many philanthropic pursuits, many of which related to healthcare and eradicating disease. He also had plans for the inhabitants and workers at Jebel Moya. Many of his efforts are effusively documented by Percy, noting how Wellcome had striven to civilise native races. Percy repeats the recurring narrative that Wellcome was initially confronted by hostile and lawless natives who were descendants of criminals. They are described as filthy, indolent, drunken and depraved and the chiefs tried to mislead Wellcome into abandoning the project, claiming there are no ancient remains (Percy Reference Percy1921).

This account needs to be placed in context. Wellcome initially wanted an extensive archaeological licence and eventually acquired a special licence that had to be renewed regularly. Initially, he was not well received by the locals – not because they were criminals, but because they were suspicious of this man's intentions. It is worth noting that the local community was well-aware of its heritage, including remains across the Gezira plain. In particular, the system of water gulleys around Jebel Moya exposed skeletal material. By 1913, Wellcome's status as the self-titled Pasha was well-established. He created a special medallion with an outline of the Gezira mountains and the words Jebel Moya. He used this logo on all correspondence from the camp (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The Jebel Moya pendant. (Photo: Wellcome Collection, archive WA/HSW/OB/B.16.)

Preoccupations with status aside, Wellcome practised a form of benevolence rooted in wider imperial policies and Christianity. Over a third of the Sudan Political Service consisted of sons of clergymen, and all came from the upper echelons of society, where Christianity certainly had a presence (Collins Reference Collins1971). The upper echelons of administration placed great value on the outward displays of Christianity, particularly after the assassination of Gordon. Islam was viewed with suspicion for political and religious reasons. Although Wellcome was not noted to be particularly religious, he certainly embraced the virtues of diligence. Wellcome's benevolence operated as follows. He offered double the normal wages and started the first bank in the area. In Wellcome's view, the natives gambled and spent too much time drinking merisa, and so he eventually switched to weekly and then fortnightly payments. Men who refrained from these pursuits were celebrated and he rewarded those who swore on the Qu'ran to abstain for life. While Wellcome was proud of his endeavours and the establishment of a bank, he was reluctant to accept the consequences of financial freedom. In a letter to Major Cameron, Wellcome addresses the objections to establishing a market at Jebel Moya. While reiterating his welfare achievements, Wellcome insists his objections are not because such a market would compete with the site canteen, which is not run for profit, but because the petitioners are ‘the chief trouble makers’ who previously relied on prostitution and the sale of alcohol. Once Wellcome eradicated such vices, these men tried to cut off food supplies to the camp and threatened the continuation of his work. In his view, a market run by these (alleged) trouble-makers would endanger the expedition. He begs Cameron to ‘rid this community of the plague of vicious diseased prostitutes’, who he blames for all the troubles at Jebel Moya as they ‘mercilessly prey’ on the workmen and ‘spread syphilis and gonorrhea in virulent form’. Wellcome assures Cameron that he is not calling for the removal of ‘all unchaste women’, just the prostitutes. It appears that Wellcome won this battle for no market was ever established at Jebel Moya.Footnote 2

Wellcome's efforts did bear fruit in the sense that many men saved money and invested it in cattle. However, when drought and famine hit the camp hard during the second, third and fourth seasons it took him a rather long time to acquire grain at a higher price. He also deepened existing wells and had ambitious plans for a well-boring project.Footnote 3 Despite investing time and money in this endeavour, the project never came to fruition, largely because of the impossibility of digging through granite. Wellcome eventually built a modern sanitary village for the non-local workers, again investing time and money, acquiring tents and other necessities. This was in line with his firm beliefs in the importance of sanitation. He also imposed other conditions on the men, including daily drills and physical exercises and participation in English field sports and other amusements.

Not content with his efforts, he also had a sermon read to all men on parade after evening roll call on 28 April 1913. Read by Sheik Maki Abu Heraz, the sermon epitomizes Wellcome's image of himself. The Sheik reminds the men that God has sent the ‘Honourable Master Mr Wellcome’, who is improving their lives and is a ‘kind father’ who loves them heartily, respects their religion, offers them prizes and spends valuable time talking to them favourably. The Sheik exhorts them to compare this with the treatment meted out by government officials.Footnote 4 Wellcome is painted as the kind master and his position as master was to raise a few eyebrows, even within the broader imperial policy of paternalism.

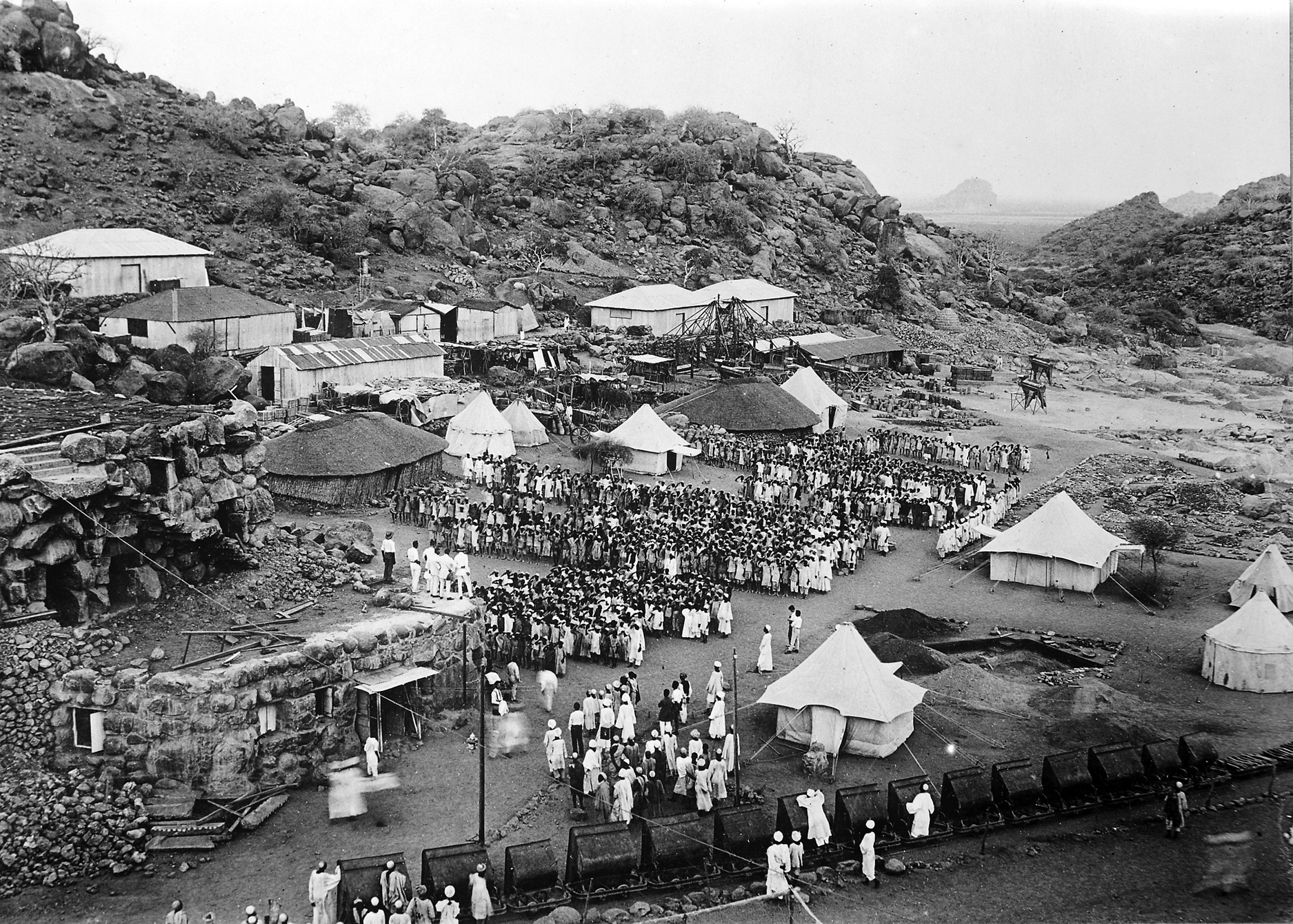

A document outlining camp rules for the 1912–13 season outlined how work was to be conducted (Figure 5). Companies (groups of 5–10 men) were led by a wakȋl. Minor offences meant a loss of pay for four to five days and serious offences resulted in a sacking. A very serious offence would see a man sacked and the suspension of part or all of the company and his kinsman. A very serious offence was defined as lying about the position of objects and introducing forged or other objects. Theft constituted a serious offence, along with striking another man and the pursuit of vices. Rewards were given for all objects, except ordinary pot sherds. Men were expected to be polite, work without idle chat and they were to be treated firmly and courteously. This firm treatment was to cause difficulties.Footnote 5

Figure 5. General view of Henry Wellcome's Jebel Moya camp (Photo: Wellcome Collection.)

The rules for white and native people varied significantly. European staff signed contracts, natives signed an indenture. The prohibition on alcohol did not apply to European staff – they were allowed beer or wine with dinner but spirits were banned except by order of the medical officer. They were also allowed to hunt after requesting permission, and all trophies belonged to the expedition. There were two types of contracts. The one for non-African workers provided for accommodation and travel. Penalties for non-fulfillment of work were not particularly severe in terms of employment standards at the time. The one for ‘natives’ is written in English and Arabic, with a very different language. Here, Wellcome is referred to as master not employer. Natives entered into service, Europeans were engaged by the employer. Natives pledged themselves to Allah and promised to be strictly obedient to the master and those in authority over them, to submit to fines or punishments, to accept termination at any time and to work hours as appointed by the master. Work would be paid ‘in such manner and at such times as the master may decide.’ The contract stipulated that it would be read by witnesses in Arabic. European staff were not required to take any religious oaths.Footnote 6

Wellcome's treatment of workers caused disquiet in many circles, particularly a case involving European staff assaulting native workmen. The matter was serious enough to warrant voluminous correspondence with Sir Reginald Wingate, Governor General of the Sudan. Wingate raised the matter with Wellcome, noting ‘silly rumours’ regarding the treatment of natives at Jebel Moya. He emphasizes that he does not credit these rumours but wants Wellcome to be aware of this irresponsible talk. Wingate concludes that the natives themselves have not complained and therefore there is no problem.Footnote 7 Wellcome admitted that he cannot enforce obedience on European workers even if they are guilty of behaving badly, but he ‘did not deem it advisable to lower the prestige of Europeans before the natives’ and complains he has spent months enduring ‘a situation that was almost intolerable’. Wellcome also admits that one of these European workmen, a ‘powerful muscular man, struck down prostrate a weak young native without the slightest justification’ and while the said workman admitted his act and defying the ‘stringent rules that no native should be struck of forcibly handled’, his hands were tied because of the ‘importance of maintaining the position of the Europeans before the natives’.Footnote 8

Wingate replies that as Governor General he cannot ignore the issue of treatment and forms of punishment.Footnote 9 He assures Wellcome that he does not believe the ‘rumours of peculiar treatment of natives’ but these could lead to ‘endless trouble and annoyance’. While appreciating his noble aims, Wingate advises ‘my many years of experience in dealing with native questions in this country have taught me that what may at first seem desirable is not always possible to carry out.’ Indeed, the system of paying workers a small sum at the end of the week and the balance at the end of the season is contrary to custom and he thus requests full weekly payments. He also notes that the natives are ‘very quick at grasping the meaning of law and order’ but any deviation from the usual punishments would ‘inevitably lead to misconceptions and very likely charges of ill-treatment.’ Wingate adds a postscript assuring Wellcome that he is ‘writing this on the representation of the Acting Governor, Sennar Province, who has brought the matter to my attention.’

James Currie, Director of Education, was also involved in the matter. Writing to Wingate he notes that Wellcome is a little hurt that Wingate gave credence to statements.Footnote 10 It appears that the matter was brought to attention by E.W. Drummond-Hay, who had a long career in the Sudanese civil service. By 1913, he had risen to the rank of First Inspector in the Financial Secretary's Office in Sennar. Drummond Hay appears to have withdrawn his complaint and Currie notes that he perhaps felt the situation ‘more keenly than he would have done under ordinary circumstances’ due to his ill health. Currie thinks that Wellcome's men are happy and supervised by competent English staff (which included Duncan MacKenzie, formerly Arthur Evans’ second-in-command at Knossos). Currie was more concerned by Wellcome's interest in acquiring unappropriated land for growing dura. Currie notes: ‘This leads up to the point that Mr Wellcome wants two things – an extension of the time of his concession, and, though he will not ask for it, the gift of Jebel Moya! He wants, I think, to be buried there, even as Cecil Rhodes rests in the Matoppos (sic), and he will bequeath all the buildings etc on it to the Government after his death.’ Currie requests Wingate to ‘enroll him (Wellcome) as a warm ally, and it is worth the trouble. From any point of view, as educator of the wildest natives (and the wilder he gets them the more he likes it) he is worth anything to me.’ Wingate is instructed to offer him ‘one or two things – things that as a matter of fact are not worth a millieme to us’.Footnote 11 These things remain unspecified and no further mention is found in correspondence.

Wingate questioned the legality of Wellcome's indenture. Wingate appears to have viewed the matter as a minor inconvenience, noting on more than one occasion that in is view this was irresponsible talk by other people.Footnote 12 Wellcome blamed his ‘insubordinate European workmen who had tried to stir up trouble amongst the natives’. As for the matter of indenture, Wellcome dismisses concerns by noting that all such contracts raise ‘possible legal hair splitting’ and the validity of an indenture can only be tested if a bona fide case arises. In his view there is no such case and is at pains to stress he has no motive to do anything improper. After all, he is carrying out ‘Scientific Archaeological Research’ and bearing all the expenses himself, while ‘Government and the people are reaping all the benefits.’ The wealthy industrialist repeats that this is not a commercial enterprise, and it is an endeavour which seeks to uplift and better natives. The fact he is investing so much of his time and money in them is proof that he is not interested in doing them wrong. Wellcome reminds Wingate that his document was drawn up by a London solicitor and ‘revised by one of the foremost avocats of Cairo and translated into Arabic under his supervision’. As such, he has taken every reasonable precaution to make it a ‘proper legal document’, contracting is voluntary and requires an understanding of the conditions. Wellcome views indenture as part of a pastoral system of welfare. In this lengthy letter, Wellcome is most outraged to have been ‘singled out’ for this treatment when there are thousands of happy and well-fed workers. He declares that Khartoum has very little understanding and appreciation of the nature of his work, carried out ‘under extreme difficulties in the most lawless and turbulent community in the Sudan’ and he has single-handedly improved the lot of natives ‘without the slightest protective assistance from the Government’. Wellcome's outrage is partly founded in his firmly held moral view of himself as the great reformer and benevolent saviour and also in his quest for a permanent archaeological licence. He ends his letter by noting that he has expended considerable money in this scientific enterprise and given the treatment he has suffered ‘I shall not be justified in arranging for an extension of my present Archaeological Excavation licence which soon expires.’ Footnote 13 Percy's account of Wellcome's ‘tribulations’ is very much reflective of this narrative that the latter was fond of repeating.

A letter from Col P.R. Phipps on behalf of Wingate states that an official received complaints from workmen and he reported this to his superior. Phipps was a Civil Secretary for the Sudan Government and had previously served as Commandant at Khartoum station. Phipps is at pains to comment that the ‘writing or receipt of such a report does not imply that the Government regards the complaints as well-founded.’ He assures Wellcome that the complaints were of so little importance that no enquiry or further action was considered necessary. However, he notes that the terms of Wellcome's contract might have resulted into difficulties and he thus suggested some modifications (not noted in the letter), but considers himself satisfied by Wellcome's explanation of the terms, ‘So long as it is carried out with the paternal care which you describe and your workmen are content I have no wish to raise technical objections.’ Phipps reiterates his appreciation for Wellcome's scientific interests and philanthropic motives, which have produced results in terms of improving industry, economy and morality. Ultimately, there were no repercussions for the assault.Footnote 14 The official response is very much in line with the policy of firm but not cruel rule. As Balfour notes in his memoirs, a common strategy was to impose a heavy sentence and then allow the legal secretary or governor general to exercise compassion and benevolence.Footnote 15 This seeming clemency was a useful tool for increasing colonial power, albeit not one used by Wellcome on this occasion.

Wellcome's problems gained traction outside of the corridors of politics. An article in the widely circulated John Bull accused Wellcome of slavery. ‘He that is Welcome does not fare well’, declared the magazine, and reminded the nation that no slaves served under the Union Jack.Footnote 16 In reality, slavery was practised in various forms across the Empire. In the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan it was quietly re-named and its practice was supported by the administration. John Bull published an extract from the contract, highlighting that a worker undertakes to submit to fines and punishments by the master. The publication declared that the terms ‘practically amount to slavery’ and that while ‘we are not prepared to take the native by the hand and call him brother, we don't like to see him defenceless against unjust and despotic treatment.’

Set up by the Independent Liberal MP Horatio Bottomley, the magazine served as a platform for his liberal views that had their own inherent paradoxes. Bottomley created a widely-read magazine fuelled by his political ambition and his knack for courting controversy. He believed that the two-party system in Britain needed to change in the wake of recent events and he mobilized a large audience in this debate (Cox and Mowatt Reference Cox and Mowatt2019). Nevertheless, slavery was not on Bottomley's agenda. In the year 1913, the only other mention is on 8 March and is a jibe at French behaviour in the New Hebrides. Bottomley spearheaded campaigns in his magazine, including taking insurance companies to task, but in the case of Wellcome this was just another provocative nugget for his readers.

The question of indenture and Wingate's advice is related to the wider slavery question faced by the Condominium Government. Following the 1898 conquest, the government engaged in a long-standing balancing act in restoring order and implementing wider colonial policies. Slavery posed a thorny question. Officially, slavery in the British Empire was abolished by the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, with exceptions provided for Ceylon, Saint Helena and the East India Company. On paper, these exceptions were eliminated a decade later. In reality, there was a widespread tolerance of slavery. Sudan had a history of slavery dating to antiquity and by the close of the nineteenth century servile labour played a major role in the economic sphere, particularly agriculture. It was ingrained in Sudanese society (Collins Reference Collins1999).

The government's aim was to prevent disharmony and so efforts focused on the appearance of dealing with the issue. Lord Kitchener classified slaves as volunteers and referred to them as ‘Sudanese’, ‘servants’ or ‘unpaid workers’ in official correspondence. In private correspondence they were referred to as crypto-servants or indentured labourers. Lord Cromer distinguished between the slave trade and slavery, pledging government support for shari'ah law regarding domestic servitude while decrying the slave trade (Collins Reference Collins1999). Meantime, some liberal-leaning members of Parliament periodically pressured the Foreign Secretary to suppress slavery in the Empire. The Condominium Government's solution in 1908 was to note that, politically speaking, slavery does not exist. Thus, while Wingate politely questioned the nature of the native contract, the matter was left to rest.

Wellcome and the construction of an image

Raised in poverty, Wellcome was not known for lavish personal tastes. His largesse was focused on his company and pursuits (James Reference James1994). Favouring a (relatively) modest abode for himself, he devoted his energies to today's equivalent of public relations. As noted in the various archives, no expense was spared in outfitting laboratories or promoting products. He also invested heavily in human resources. Aside from paying the Sudanese above-average wages, he also ensured that workers in Britain received a good pay and other perks. Always impeccably dressed, Wellcome had a carefully curated public image, whether in London high society or at the remote Jebel Moya camp. The investment in advertising his company did not extend to his personal life, choosing to keep the breakdown of his marriage under wraps until his former wife was pregnant with someone else's child and, with some exceptions, declining to give interviews about himself or his archaeological project.Footnote 17

At Jebel Moya, Wellcome appointed Julian Sergio Uribe as Camp Commandant. Uribe credited Wellcome with saving his life. Although only rumours survive, Kirk notes Wellcome's alleged rescuing him from bandits in South America ‘would fit in to the fantastic fairy tale of the life of Wellcome’ (Kirk Reference Kirk1956). In reality, Wellcome met Uribe while in Quito. At the invitation of the American Secretary of War, J.M. Dickinson, he was inspecting the Panama Canal Zone. In Quito, Jordan Stabler, then at the American legation to Ecuador, asked Wellcome to take Uribe to England because as a former political prisoner he was in grave danger (James Reference James1994). His task was to oversee the work and, to an extent, the village. He also advertised widely for archaeologists and geologists and received numerous applications.Footnote 18 However, it was Uribe who provided the backbone of this project. Uribe and Wellcome had a complex relationship, Uribe was a devoted employee and Wellcome also influenced his private life. Uribe writes to Wellcome that there is a girl in Spain he wishes to marry. He states he has no other home outside of the camp and would hope that the unnamed woman could join him there, obsequiously requesting Wellcome to allow him this concession. Wellcome replied to Uribe that marriage would be unwise and undesirable and that wives were prohibited in the Sudan as they would be unable to withstand the challenge of living there. Uribe, in his reply, thanks him profusely for his advice and for saving him from committing a grave error.Footnote 19 Wellcome's views on marriage had previously driven a wedge between him and Silas Burroughs (James Reference James1994). More broadly, however, the administration discouraged the presence of Western women.Footnote 20 Lord Kitchener, for example, refused to enlist married or betrothed men and employees of the SPS were forbidden from marrying during the two-year probationary period. The presence of women only increased after World War I.

Still, Uribe remained preoccupied about his future and at one point considered returning to his native Colombia. Wellcome reminds him that he has entrusted him with command of his affairs at Jebel Moya ‘because of your long and intimate association with me and the training you have received, giving you special and intimate knowledge of my work and of my policy in dealing with the natives and others.’Footnote 21 Wellcome wanted Uribe to stay behind because he had grand plans for the Gezira plain. Uribe's task was not just to supervise the camp and its activities, but also to ensure that Wellcome's interests were protected. Wellcome spent many years and much effort helping Uribe obtain British citizenship, personally writing to the Secretary of State and vouching for Uribe. Uribe's application was also supported by Sir Reginald Wingate.Footnote 22

Records are incomplete, but by 1938 Uribe is married, as recorded in a letter to Ada Misner, Wellcome's long-standing personal assistant. Further correspondence also mentions children. In the same letter, it is clear that operations at the camp are being wound up. Uribe writes: ‘For the last time I am out amongst my Sudanese friends whom may God help as in ages past for as far as we are concerned they are to be forsaken.’Footnote 23 As Europe was on the brink of war, the situation in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan was increasingly complex. The emergence of Sudanese nationalism and its efforts to restrict the governor general's power contributed to rising tensions. The 1936 Treaty of Alliance set a time-table for the end of British military occupation, with no agreement reached between Britain and Egypt regarding Sudan's future status (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The Wellcome-Uribe commemorative plaque in the House of Boulders. (Photo: Isabelle Vella Gregory).

Wellcome was very adept at leaving a positive impression on people he met along the way.Footnote 24 Other employees had a more measured view of Wellcome. A letter from a W.J. Britchford outlines how the former worked for Wellcome initially as a joiner and then setting up the museum. Britchford mentions Wellcome's exactitude and his penchant for expecting people to solve problems. He recalls: ‘One of the things about Sir Henry was that he never thought he would die. He would talk about things he wanted done in five years’ time and ten years’ time.’ By then, Wellcome's health was ailing and he constantly summoned Britchford to his hotel. Britchford realised that Wellcome was lonely and he was desperate to talk to somebody.Footnote 25 Writing to Ada Misner, Uribe comments: ‘Sir H was happy though a lonely man, it could not be helped; he was born to rule at any cost. His main concern was his name and its future, he knew that the evil that men do – even to few – is buried in their bones while the good lives on after them.’Footnote 26

Keen to have his archaeological and scientific contributions recognised by his peers and beyond, Wellcome fostered his friendship with George Reisner, whose field methods were considered revolutionary at the time. Reisner and his wife visited Jebel Moya, and Wellcome appeared to be content to overlook his ‘no women’ rule. In a letter to Currie, Reisner noted he had spent fourteen days directing excavations himself, he is certain that ‘nowhere else in the whole of Africa has any Negro site of this antiquity been discovered’ and since Wellcome is the only person who has the interest and material means to fund such a project he should be given licence to excavate other sites.Footnote 27 Reisner's efforts may not have had the desired effect across the board. Kitchener writes to Wellcome that he has been informed of Reisner's visit and opinions by Currie, and notes ‘It must be most gratifying to you to have your conclusions verified by such an authority, and the results you will be able to produce will be of exceptional interest.’Footnote 28

Although his health was failing, Wellcome was keen to return to Jebel Moya at the end of World War I. The question of licences became more thorny. A series of letters illustrate the problem. A long letter to Sir John Maffey asks for a resumption of work. Wellcome reminds Maffey of his enormous contribution to the war effort and Uribe's diligent supervision of the site during this period. He reminds him that from the beginning, Special Licences were dealt with personally by the Governor General in office. His last one had been granted by Sir Lee Stack for a term of five years, terminating in December 1925. Wellcome complains that upon application for an extension, he was granted a different licence. This was never ratified, due to his ill health and his welfare work with Alaskan natives. Wellcome reminds Maffey that the terms and conditions of these licences are related to the exceptional nature of the sites and his welfare work and officials had taken into consideration ‘the fact that I alone bore the whale of the expense of the work, and that none of the materials or objects excavated at these sites had any real intrinsic value, but were of purely technical scientific interest as examples of primitive indigenous African culture. Such archaeological work involves infinitely greater care and detail manipulation than is required in the excavation of archaeological sites of highly developed peoples.’Footnote 29

Wellcome goes to great lengths to explain to Maffey how Wingate and Currie personally visited Jebel Moya and inspected his work, and that perhaps the change in terms and conditions is due to officials who are unfamiliar with archaeology. While he acknowledges that new development schemes and changes in labour wages have taken place, he is most outraged at the change in custom when it comes to terms and conditions. A further letter thanks him for his assurances and variable attitude regarding a licence similar to the ones he had been granted in the past. The colonial powers appear to have had concerns regarding labour availability, as Wellcome assures Maffey that his need for labour will not present any difficulties, reminding him that when the Sennar irrigation canal was constructed in 1913–14, some of his highly trained men joined the project but none came over to join the excavation. He assures Maffey that he ‘would not wish to do anything detrimental to the interests of the Government or prejudicial to any private agricultural or other enterprises.’ Wellcome writes that back in 1910 he had discovered numerous sites and while Government officials had encouraged him to abandon the project, because they could not guarantee his safety, he soldiered on. He emphasizes he only acquired rifles, sanctioned by officials, to appease their worries. These rifles and ammunition were kept in a secure vault and their presence was not disclosed to the natives.Footnote 30 The Governor's apparent concern about weapons is related to the difficult political situation in the Sudan, especially after the assassination of Lee Stack in 1924 while he was in Cairo. Wellcome never returned to the Sudan, he passed away in 1936.

Wellcome was a key figure in disseminating the archaeology beyond the Sixth Cataract to western audiences, but he was not its architect. Wellcome constructed an image built on his vision of the world, a vision which aligned with the broader British imperial policies. In many ways, the architect was the resulting mythology that Wellcome built around the site and the anticipation of the publication of the data. Jebel Moya faded from memory until very recently.

Jebel Moya and colonial policies

Uribe's prediction that Jebel Moya would be abandoned and ‘populated by dreadful ghosts and afrits’ held true until the twenty-first century.Footnote 31 The data available in the UK was re-examined by Michael Brass and excavations were re-opened in 2017 (Brass et al. Reference Brass, Fuller, MacDonald, Stevens, Adam, Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin, Abdallah, Alawad, Abdalla, Vella Gregory, Wellings, Hassan and Abdelrahman2019). The current project is very different in scope. As Tilley (Reference Tilley, Tilley and Gordon2007) has argued, there is a broader question about the medium for gathering information on Africa and whom this was for. With reference to the Sudan, there are various intersecting points to note.

In terms of education, there was a reluctance to introduce a western-style system (Tignor Reference Tignor1966). The ‘problem’ of educating natives had aided the rise of a westernised political elite in places like India, much to the chagrin of the imperial government. The rise of a similar elite in Egypt would have been most unwelcome. The overwhelming narrative, therefore, was one of lazy and child-like Sudanese who needed careful instruction that was not particularly taxing. Cromer laid the foundations for an education system closely tied to the government bureacracy, ensuring sufficient human resources that fit within the broader governmental aims.Footnote 32 The infantilization of the Sudanese is a constant theme, not just in Wellcome's papers but also in administrative sources. Douglas Derry, for example, was appointed as the Jebel Moya anatomist during the second season. At no point does he train any Sudanese or allow them to participate in the work. In his role as assessor for the medical school, he adopted teaching methods viewed as suitable for the ‘not naturally deductive’ Sudanese (Bell Reference Bell1999).

By contrast, the government actively promoted anthropological instruction for staff. This was necessary in a large country devastated by war and lacking infrastructure. Initially, the administration relied on nineteenth century accounts by travellers, soon supplanted by field reports from military and administrative officers on the ground. James Currie and his successor J.W. Crowfoot were keen on improving local education (Currie Reference Currie1934; Reference Currie1935). In 1910, the Government hired Charles and Brenda Seligman for an expedition to the Upper Nile. The motives were not purely anthropological and, as Johnson notes, when writing to the Financial Secretary Currie dismissed any urgent necessity for studying things like racial affinities or primitive arts and crafts. His focus was on laws and social organization (Johnson Reference Johnson, Tilley and Gordon2007). The Government had an interest in local laws and customs as part of their strategy to utilize them as part of the general administration of the Sudan.

The impact of such policies has been widely debated. Asad (Reference Asad and Stocking1991) claims that anthropology's role in maintaining the structures of imperialism was trivial. Perhaps it was in terms of financial investment, of which even less was dedicated to archaeology. Indeed, Wellcome funded the project at great personal cost. While Currie and others did not see the excavation of a ‘peripheral’ site as particularly useful to the colonial cause, anthropology most certainly provided a knowledge-base for the construction of colonial states. Ahmed's stance that the administration's main objective was control of the ‘natives’ is largely correct, as is his observation that the anthropologist was writing to an administrator (Ahmed Reference Ahmed1982). This was certainly not the case everywhere, particularly in the work of Audrey Richards (Reference Richards1944). Furthermore, while administrators tried to standardise anthropological inquiry with a list of questions, no such restrictions were imposed on archaeology. Perhaps this is reflective of the greater perceived practical value of anthropology. Indeed, when in 1937 A.J. Arkell was appointed government anthropologist and archaeologist, the administrators were not particularly happy with his focus on archaeology and by 1940 they had created an Anthropological Board, managed by the Civil Secretary Chairmanship. After World War II, the position of Government Anthropologist was separated from archaeology.

Arkell organized the Sudan Antiquities Service as a government branch and trained the first Sudanese inspectors. He conducted surveys and had a direct interest in prehistory, rather than Nubian archaeology. Nevertheless, Jebel Moya remained outside the interest of archaeologists, as did much of the area south of Khartoum unless it was related to Kush and Meroe. The lure of the monumental has diverted many an archaeological inquiry in the Sudan. It has resulted in an emphasis on Nilotic archaeology north of Khartoum, including a strong focus on the Kerma, Napatan and Meroitic pyramids. In the last four decades, however, there has been a shift to launch missions in areas outside of the Nile valley (see, for example, the summary in Edwards Reference Edwards2004 and the December 2019 issue of Azania). Despite this latter point, and arguably because it does not contain any known prehistoric monuments, the south-central Sudan remains neglected.

The seeming disconnect between archaeology and anthropology is very much related to colonial interests. The Sudan provided ground-breaking work on the Nuer, Azande, Nuba and the Dinka (Evans-Pirtchard Reference Evans-Pritchard1937; Reference Evans-Pritchard1940; Nadel Reference Nadel1947; Leinhardt Reference Lienhardt1961). Interest in Sudanese matters was not exclusively western, as Ahmed (Reference Ahmed1982) notes, Arab travellers also gave accounts of the Sudan, for example Ibn Umar al-Tunisi's book on Dar Fur (1850) and the Sudanese scholar Muhammad al-Nur Ibn Daif Allah's 1805 Directory of Saints, Holy Men, ‘Ulama and Poets in the Sudan. The former was a learned member of a prominent Tunisian family and the latter was a historian.

Archaeology's trajectory is somewhat different. Central to this is the question of Egypt. If the Lower Nubia area is included within the Sudan, then the story begins in the nineteenth century with Giovanni Belzoni's explorations. At this time, Sudanese remains in Lower Nubia were seen as a devolved form of Egypt ‘proper’. Many figures at this time, such as A.E. Wallis-Budge, were primarily linguists rather than archaeologists and did not stray too far into the Sudan. The exception was Karl Richard Lepsius, a Prussian Egyptologist with a deep interest in archaeology. Lepsius explored the Sudan, travelling to Khartoum, up to the Blue Nile and Sennar. He included these antiquities in his Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia.

The next major contribution is by George Reisner, who surveyed Nubia and worked extensively in the northern Sudan. His enthusiasm for Wellcome's project was borne out of a genuine desire to understand Sudan beyond Khartoum, although he understood this region from the lens of Egyptian archaeology. Wellcome's motives, however, were due to personal interest rather than any comprehensive research question. That they were in line with broader colonial ideas was a convenient happenstance. Wellcome's interest in native welfare was genuine insofar as it was defined by the standards of the time. The Sudan had evolved out of a ruinous war and the British government never quite restored the country successfully. Colonial policy in the Sudan remained ‘benevolent’ as late as the 1930s. Margery Perham, historian, authority on colonial Africa and policy advisor (among other things) was an emphatic believer in the virtues of British colonial rule, as long as it was benevolent towards the indigenous population. She advocated for self-government as defined by British policy and in 1936 presciently noted that African nationalism would rise as a result of colonial policies and one must ensure it is done constructively (Perham Reference Perham1967). Wellcome's benevolence was very different and this is most starkly seen in the difference between European and ‘native’ employee contracts.

This leads back to Tilley's question on who served as a medium for gathering and disseminating knowledge and the role of Africans in shaping research. While Wellcome's laboratories in Khartoum trained some Sudanese (albeit in minor roles) and the Government trained locals in a number of areas, Wellcome took a very different approach to archaeology. His mantra of benevolence did not extend to training any Sudanese in archaeology. Neither did he acknowledge their contribution. By contrast, although Howard Carter's records do not identify indigenous workmen by name, he acknowledged his four ruʾasāʾ by name in the first two books about Tutankhamun. And yet, as Riggs further notes, the photographic records of the time very much attest to the asymmetries and inequalities on excavation (Riggs Reference Riggs2017). The same applies to Jebel Moya. Wellcome viewed his workmen as commodities that had to be trained to perform according to certain standards. They were part of the machinery of his project, without explicitly acknowledging their essential role. Wellcome entrusted archaeology to a select number of people, and that excluded the loyal Uribe who spent decades on the camp but was not allowed to carry out any research. For Wellcome, and many others, archaeology was defined as the actions of white men who knew the native and how to handle him.

Narratives of Jebel Moya

Wellcome's need to control the narrative of his work included requiring his final approval prior to publication, limiting publications with some exceptions and writing to various important people about his achievements. In a letter to James Currie, he highlights his endeavours and discoveries, including ‘unmistakable proof of long-continued habitation (…) at a very early period.’ He repeats his trials and tribulations in obtaining labour and his benevolent response and then tells Currie all about the finds and his discovery of ‘several other sites’ which he has ‘reserved for future investigation’.Footnote 33 Currie's response is not recorded, but in his 1934 paper on education in the Sudan he mentions Wellcome in passing, noting how his munificence enabled scientific studies to start earlier in the Sudan (Currie Reference Currie1934). Wellcome broadcast his achievements widely. In October 1912 he sent several (nearly identical) letters to a number of distinguished people, informing them of his discovery of a prehistoric site and ‘objects illustrative of the life and industries of early primitive races’ and offers to show them these objects. Letters were sent to Sir Lauder Brunton (the Scottish physician associated with the use of amyl nitrite to treat angina), Sir Hercules Read (Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography at the British Museum and President of the London Society of Antiquaries), Sir Edwin Ray Lankester (director of the Natural History Museum) and Prof. Édouard Naville, archaeologist and Biblical scholar.Footnote 34

Wellcome read his paper titled Remains of primitive Ethiopian races discovered in the southern Sudan at the British Association for the Advancement of Science. This is not an academic contribution, but it does have the now-familiar refrain on lawless natives. He summarized his excavations and declared that ‘the human remains were of several types and many of them indicated a race or races of large stature.’ An identical undated version of this paper in French was addressed to the Congrès archéologique: the only addition is a comment that this is the region where one should search for the origin of humankind.Footnote 35

Reisner's (Reference Reisner1918 a/Reference Reisnerb/Reference Reisnerc; Reference Reisner1919) four-part narrative of the ancient Sudan in SNR is the trajectory of the Sudan via the lens of Egypt. He starts by viewing Sudan as part of the southern districts of Egypt, arguing that the results of his survey show that by the Sixth Dynasty, the population had lost its Egyptian character ‘and had become the curious negroid race which is hereafter known as the Nubian race’ (Reisner Reference Reisner1918b, 8). In the Middle Kingdom Sudan is subjugated by Egypt and lower Nubia is run by what Reisner terms an incompetent, backward race, with ‘civilization’ only existing in the Egyptian forts and colonies. Reisner then shifts the narrative to the Kingdom of Kush, and in the final part of his narrative he declares Wellcome's work as the first recorded archaeological site in the interior of Africa. Reisner postulated that Jebel Moya was typical of all (undiscovered) villages in the inner Gezira. Jebel Moya had direct trade connections with Napata and the Kushite kingdom and it was populated by a mixed race with ‘negroid characteristics, not greatly unlike the present inhabitants of that district’ (Reisner Reference Reisner1919, 67). Ultimately, he concluded that the most important archaeology existed to the north of Khartoum and considered the area south of Khartoum a place where the ‘fine trades of the educated and skilled Egyptian were visibly fading into the coarse features of a negroid race which may have been slow at forgetting but was incapable of giving a creative impulse to art, learning, or religion’ (Reisner Reference Reisner1919, 67).

Publication of the site would only see the light of day in 1949 by Frank Addison and skeletal material was re-analyzed in 1955 (Addison Reference Addison1949; Mukhrejee and Trevor Reference Mukherjee, Rao and Trevor1955). A common theme in the discussion of skeletal material is the issue of race. Derry (Reference Derry1914) spoke of unusually tall people whose measurements defined them as ‘negro’ but with less marked features than neighbouring populations and more akin to the ancient Egyptians. Derry used measurements set out by Karl Pearson, a disciple of Francis Galton and a keen champion of eugenics (Challis Reference Challis2013). While references to eugenics are conspicuously absent, it is clear that academics and colonial administrators were keen to distinguish between ‘true negroes’ and the Sudanese. Addison (Reference Addison1949, 254–5) declared Jebel Moyans to have affinities with southern Sudan and the admixture of features was assigned to enterprising and predatory people who enslaved women from various tribes. Much later, Mukherjee and Trevor (Reference Mukherjee, Rao and Trevor1955, 99) argued that Jebel Moya is racially dissimilar from comparanda, being composed of ‘a robust Negroid people allied to and resembling, at least to some extent, the present-day Negroids of the Sudan who claim to have formed the oldest settlement in that area.’

After this, Jebel Moya all but disappears from the archaeological narrative. Randi Haaland (Reference Haaland1984) and J. Desmond Clark (Reference Clark1973; Clark and Stemler Reference Clark and Stemler1975) used Addison's descriptions to conclude there are similarities between Jebel Moya and Butana ceramics. Isabelle Caneva (Reference Caneva1991) identified a Mesolithic component to the Jebel Moya pottery collection at the British Museum and Rudolf Gerharz (Reference Gerharz1994) revisited the issue of chronology. This relied exclusively on Addison's dataset, with no attempts made to examine extant records or assemblages. The next publication, based on an extensive re-examination of records and pottery assemblages curated in the United Kingdom was by Michael Brass (Reference Brass2016). Excavations resumed in 2017 and its findings are revising our understanding of both the archaeology of the Gezira Plain as well as the chronology of sorghum domestication in the eastern Sahel (Brass et al. Reference Brass, Fuller, MacDonald, Stevens, Adam, Kozieradzka-Ogunmakin, Abdallah, Alawad, Abdalla, Vella Gregory, Wellings, Hassan and Abdelrahman2019). Outside of African archaeology, Henry Wellcome remains predominantly known as a pharmaceutical pioneer, philanthropist and collector.

Conclusion

The history of Jebel Moya, the Sudan and colonial Africa is tethered to the idea of knowing the native. In this endeavour, the colonial administration afforded this agency to the white researcher, whether they were anthropologists, archaeologists, members of the civil service, military, etc. Wellcome, like many others, was able to claim with authority that he knew the native, both in the past and the present. Chinua Achebe (Reference Achebe1975) has argued that knowing the natives implied that the native was simple, and understanding and controlling him went hand in hand.Footnote 36 This was certainly the case in the Sudan, more broadly and particularly at Jebel Moya, as is especially evident in Wellcome's refrain on welfare. The administration and archaeologists dedicated a lot of time to defining racial identities, both in the Sudan and elsewhere. The discourse was not restricted to the colonies and infiltrated socio-politics within the United Kingdom. In the Sudan, the North (Arab)–South (black) divide is a contested political definition. James notes that distinctions are largely based on status, not ethnicity as defined by the west, and outside of the elite there are high rates of intermarriage across social and ethnic lines (James Reference James and Jain1977).

Claims of knowledge were tied to ‘knowing the native’, but (until recently) no attempt was made to listen to indigenous voices. In particular, relatively little is known about the ancient and present inhabitants of Jebel Moya. We know significantly more about the former, but hardly anything of the ones but hardly anything about Wellcome's large crew of workers. While there is some information concerning excavators like Oric Bates, very little is known about Sergio Uribe and hardly anything is known about the large number of Sudanese workers. Some are captured in photographs, carefully posed for the western gaze. Their role is being investigated. Furthermore, the current project, co-directed by a Sudanese and a South African, established a different agenda from the outset. The excavations have the full blessing and participation of the present inhabitants and Sudanese students are a core part of the project, which now includes discovering the active voice of the present-day inhabitants.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the community at Jebel Moya, on whose land this project is conducted. The author is grateful to reviewers for their feedback. I am grateful to Alexandra Eveleigh and Angela Saward (Wellcome Trust) for their enthusiasm, support and help. Thanks are also due to the wonderful staff at the Wellcome Collection archives and digitization department. The excavations are funded by the Society for Libyan Studies; however, this particular research was carried out independently and no funding was received.