Existing research on cabinet formation in presidential systems has offered key insights on the chief executive's appointment strategy. According to the literature, presidents with limited policy-making power tend to form a cabinet with more partisan ministers in order to reinforce support for their policy program (Amorim Neto Reference Amorim Neto2006). When their party does not control a legislative majority, presidents are more likely to concede cabinet posts to opposition parties, thereby shoring up support for their policy agenda (Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007; Cheibub, Przeworski, and Saiegh Reference Cheibub, Przeworski and Saiegh2004). When institutional circumstances allow for effective control of their party, presidents are more likely to appoint copartisans versus nonpartisans to the cabinet in order to limit agency loss (Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015).

While these studies contribute to an understanding of the role of cabinet appointments in achieving policy goals, they fail to recognize that cabinet portfolios are not all equivalent; instead, specific posts are better suited to advance particular goals.Footnote 1 On the one hand, cabinet posts in key policy areas, such as economic management, directly determine the government's overall reputation; on the other hand, positions in the policy areas represented by organized interest groups help to enhance the administration's governability. Existing research suggests that a variety of cabinet posts have been classified by the degree of their prestige or their gender type (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012), but little is known about how these posts can be categorized on the basis of a president's policy purposes.

In this article, I develop a theory that explains portfolio allocation as an instrument of presidents' efforts to fulfill their dual policy objectives, which often become a trade-off under the institutional separation of powers. As national leaders, presidents would like to appoint as many loyal and competent agents as possible to implement the policies promised in their electoral platforms; but as heads of government and party leaders,Footnote 2 they also need to use cabinet appointments to secure support from the legislature and the ruling party. Successfully balancing these incentives allows presidents not only to gain loyalty and expertise in key issue areas but also to benefit from legislators' experience and influence necessary to formulate and implement their program.

In light of this, how do presidents distribute cabinet portfolios to ministers for their policy goals? I argue that the posts wherein ministers can influence the government's overall reputation through the delivery of policy commitments in key issue areas are most likely to go to nonpartisan professionals who are ideologically aligned with presidents, while the posts wherein ministers can exert legislators' influence for the sake of the administration's governability in policy formulation and execution often go to senior legislators from the president's own party. These patterns are more likely to occur with an increase in the president's support in the legislature, because presidents can afford to strongly exert their preferences over portfolio allocation under such conditions. To test these claims, I use an original dataset on the composition of presidential cabinets in South Korea (henceforth Korea) between 1988 and 2013. I find strong support for this logic with multinomial logistic regression analyses.

Korea provides an excellent case for examining presidential portfolio allocations because we can systematically distinguish incentives to appoint nonpartisans versus party members to particular types of cabinet posts. Facing an assertive legislature and organized interest groups that have gradually constrained executive authority after democratization, Korean presidents are pressured to accommodate their interests in the government. Yet, parties in Korea are not as institutionalized as those in advanced democracies (Dalton, Shin, and Chu Reference Dalton, Shin and Chu2008). To gain high levels of loyalty in implementing their important policy promises, presidents may appoint nonpartisan professionals whose policy preferences are compatible with them. In Korea, where regional politics has historically functioned as a cue about a candidate's political views and beliefs (e.g., Kang Reference Kang and Kim2003; You Reference You2015), we are able to observe whether presidents have consistently allocated key cabinet posts to appointees who share their regional ties. In addition, focusing on presidents with constitutionally mandated single five-year terms enables us to conduct an empirical analysis of portfolio allocation while controlling for country-level factors shaping presidential incentives.

In the next section, I first discuss a range of challenges faced by presidents of new democracies, focusing on the two most important policy goals of every chief executive: building political support for their policy program and delivering their policy commitments to the public. Then I examine how the institutional separation of powers shapes presidential incentives to choose nonpartisan versus copartisan ministers. Given the nature of the trade-off, I further predict how presidents make portfolio allocations by distinguishing specific types of cabinet posts when appointing copartisans and nonpartisans and how the distinct patterns of portfolio allocation can change in crucial political contexts, such as the president's support in the legislature.

PRESIDENT'S POLICY GOALS, PORTFOLIO ALLOCATION, AND POLITICAL CONTEXT

Presidents of new democracies face a range of challenges and often address them with executive resources such as cabinet appointments (Amorim Neto Reference Amorim Neto2006; Chaisty, Cheeseman, and Power Reference Chaisty, Cheeseman and Power2014; Geddes Reference Geddes1994; Martínez-Gallardo Reference Martínez-Gallardo2012). On one hand, these challenges include generating broad legislative support for necessary reform program for the purpose of consolidating the institutions of democratic rule. With diverse issues threatening government stability, presidents will be pressured to compose their cabinets with representatives from a variety of political persuasions and at least may attempt to secure sufficient legislative support for their leadership. On the other hand, presidents need to recruit policy experts who are reliable enough to put the president's program above individual political agenda. In other words, chief executives need executive agents that are administratively efficient and politically loyal. In presidential democracies, executives' ability to keep their promises to the public is important in the eyes of the voters, and the presidential capacity to accomplish their policy agenda tends to be “a necessary condition for a successful presidency” (Mainwaring and Shugart Reference Mainwaring, Shugart, Mainwaring and Shugart1997). In sum, a presidential cabinet should reflect presidents' calculations regarding policy and political challenges they might face.Footnote 3

How would we expect presidential cabinets to be organized around their dual objectives? Understanding how presidents allocate specific types of cabinet portfolios to different ministers is more complicated than simply considering how the institutional separation of powers conditions presidential incentives to choose ministers, although I agree this is an important place to begin. Existing studies suggest that presidents face different incentives than prime ministers to appoint their party members to the cabinet due to the nature of the relationship formulated in a given constitutional design (Amorim Neto and Strøm Reference Amorim Neto and Strøm2006; Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015; Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010). In parliamentary democracies, where a single chain of delegation links the voters' choice of parliamentary members to the formation of a government by the prime minister (Strøm Reference Strøm2000), the incentive to appoint copartisan ministers is compatible with parliamentarians' objective, because “party affiliation ensures that ministers share with the legislators who empowered them the aim of serving the party's electorate and delivering the party's policy commitments” (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010, 1425).

By contrast, in presidential democracies, where chief executives and legislators are elected by a different set of voters, appointing copartisan ministers may lead to divergent preferences over the direction of policy agenda (Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015; Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010). While presidents serve a single national electorate and appeal to a broad voter group, their party may intend to serve more narrowly targeted interests for their local constituents. Partisan ministers therefore find themselves “subject to pressures to pursue the policy aims of two competing principals, the legislative party and the president” (Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015, 236). On the other hand, by appointing nonpartisans, presidents can enjoy a high degree of ministerial loyalty. Nonpartisans are often chosen from the president's inner circle or a pool of candidates who are ideologically compatible with the president.Footnote 4 They often stay outside politics after serving as cabinet members (Blondel Reference Blondel, Blondel and Jean-Louis Thiébault1991). Moreover, by naming nonpartisans, presidents can recruit executive talent from an external pool and are not restricted by the limited talent available in party organizations in new democracies (Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2014). Nonpartisans are typically regarded as experts in their fields as they are often hired based on their professional backgrounds (Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán Reference Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán2015). In sum, the choice of nonpartisan cabinet ministers signals presidents' commitment to effectively delivering their policy promises.

This leads to the question of how presidents will distribute specific cabinet portfolios to nonpartisans and copartisans. In general, the presidency is remembered in history for its performance and legacy in key policy areas, such as economic management, internal and foreign affairs, and national defense. These policy areas are described as “high” in the sense that they are “among the most visible and important responsibilities that a [president] has to manage while in government, and in which alleged failures by incumbents will form a key component of an opposition case against the government” (Shugart, Pekkanen, and Krauss Reference Shugart, Pekkanen and Krauss2013, 5; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2005; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012). Qualified candidates for the posts should be willing to put loyalty to the president's agenda above personal political interests and must be competent in the issue areas. In forming a cabinet, presidents will therefore delegate posts in “high-policy” areas to those who are most reliable and competent, as they most directly determine the government's overall reputation. These posts are thus more likely to be given to nonpartisan professionals who are ideologically compatible with the president than to politicians whose preferences may differ from the president's policy agenda.

But presidents also value the political leverage of their government, which complicates how their incentives can affect portfolio allocation. Cabinet appointments should therefore also reflect presidents' desire to shore up their support in the legislature or their own party. There are some policy areas where appointees' political backgrounds and experience are considered more important than other credentials, serving as “a marker for the legislator's power and influence” (Pekkanen, Nyblade, and Krauss Reference Pekkanen, Nyblade and Krauss2006, 187). When organized interest groups exist in the policy areas, presidents may name candidates who are perceived to represent their groups' interests or who can respond to these groups acting for the chief executive. In other cases, appointees are expected to coordinate between the executive and the legislative branches or the ruling party in order to facilitate the passage of the president's policy program. It therefore makes sense to delegate the exercise of legislators' influence that helps to enhance the administration's governability in policy formulation and implementation to senior politicians. These “political-leverage” posts are likely to be granted to members of the president's party who have extensive experience with the legislature. It is also in the president's interest for future presidential candidates in his party to develop the background necessary to successfully govern the executive branch.

In short, I suggest that current comparative studies analyzing the president's calculations in achieving policy goals generally overlook this important factor in explaining cabinet appointment—presidents value both the delivery of their key policy commitments and the maintenance of their administration's political leverage, and they organize their cabinets to promote these dual objectives. Essentially, presidents face a trade-off between the two components: as national leaders, they may want to choose ministers beyond the party platform; yet they also need members of their own party who can provide the connection between the legislative and the executive branches and help them to secure support from their own party (Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015). Thus, cabinet appointments should be influenced by presidents' desire to effectively deliver their policy promises, as well as by their interest in their administration maintaining strong political leverage.

Portfolio Allocation under Political Context

Portfolio allocation does not operate in a vacuum, however, but in specific contexts where presidential incentives can change significantly. In fact, presidents periodically reshuffle their cabinets, thereby adjusting to the variations in political and economic contexts during their terms (Lee Reference Lee2018a; Mainwaring and Shugart Reference Mainwaring, Shugart, Mainwaring and Shugart1997). Among a variety of circumstances that may shape these incentives, the president's support in the legislature has been shown to be one of the most influential aspects (Amorim Neto Reference Amorim Neto2006; Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007; Cox and Morgenstern Reference Cox and Morgenstern2001; Shugart and Mainwaring Reference Shugart, Mainwaring, Mainwaring and Shugart1997), because it directly affects a president's political costs and benefits for appointing specific types of ministers to a post.

Presidential effectiveness in lawmaking depends largely on their “abilities to shape or dominate the lawmaking process that stem from the president's standing vis-à-vis the party system” (Shugart and Mainwaring Reference Shugart, Mainwaring, Mainwaring and Shugart1997, 13). When their party commands a legislative majority, presidents see their agenda more easily approved (Cox and Morgenstern Reference Cox and Morgenstern2001), and the incentives to seek additional political support are weak. Presidents with strong legislative support have more leeway in distributing cabinet resources, and they thus do not pay the cost of distributing scarce cabinet resources that they could concede to opposition parties for coalition formation when they allocate posts according to their preferences. On the other hand, when their party holds a legislative minority, presidents have stronger incentives to use cabinet appointments to build coalitional support for their program (Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007). In this case, the benefit of forming a coalition is greater for presidents, and the cost of not bringing other parties into the cabinet can be high (Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007; Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007). Since presidents administering a minority government are more constrained to exert their preferences over portfolio allocation, we are less likely to see the portfolio allocation patterns depicted above.

Although my theory should be generally applicable to cabinet appointments in all presidential democracies, the specific application of this theory to young democracies provides an ideal opportunity to test it. For example, in young democracies, where parties are not as institutionalized, presidents tend to have limited capacity to hire executive talent within the party organization (Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2014). In this circumstance, I would expect presidents to rely on a talent pool outside the party to ensure the implementation of the key policies promised in their platforms, while delegating authority to exert legislative influence to their party members. In addition, young democracies are typically characterized by more fragmented and immature party systems, which tend to be conducive to multipartism in the cabinet. In this context, presidential incentives for cabinet appointments and coalition formation are more closely tied to the level of copartisan support in the legislature.

ANALYZING PRESIDENTS' PORTFOLIO ALLOCATIONS IN KOREA, 1988–2013

Hypotheses

My analysis focuses on executive portfolio allocations in Korea after its 1988 democratic transition. Korea is a useful case to examine how presidents in young democracies exercise their preferences over portfolio allocation in achieving policy goals, because presidents of Korea maintain nearly exclusive control over cabinet formation, including appointment and dismissal of cabinet ministers (Hahm, Jung, and Lee Reference Hahm, Jung and Lee2013; Hicken and Kasuya Reference Hicken and Kasuya2003; Kang Reference Kang, Dowding and Dumont2015; Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992). In Korea, appointing a prime minister requires legislative consent, but, even in this case, presidents still hold unilateral authority to dismiss her.Footnote 5 Since appointing other ministers does not require legislative consent, and a prime minister cannot override presidential appointment decisions, Korean presidents have full discretionary power to select most cabinet members. Presidents usually determine specific post allocation in close consultation with their chief of staff in the Blue House.Footnote 6 Even when negotiating with other parties in the legislature over potential coalition formation, presidents, rather than their parties, are the central decision makers.

According to scholars of the Korean presidential system, cabinet posts tend to be allocated along a separate track, with particular types of ministries each featuring ministerial appointees with distinct characteristics (Park, Hahm, and Jung Reference Park, Hahm and Jung2003). Specifically, there are three types of ministerial party affiliation: members of the president's party, members of other parties, and members with no party affiliation (i.e., nonpartisans). I also divide the posts into three broad issue areas: those that have generally been in the most important policy areas (high-policy), those concerning policy areas that are less salient but with organized interests (political-leverage), and those in the policy areas that are less salient and with dispersed interests (low-profile). The details of how each cabinet post is classified into three issue areas are discussed below.

How do presidential incentives for portfolio allocation vary among these types of posts? Based on my theoretical framework, the most significant distinction is between high-policy and political-leverage posts. While the former positions are linked to appointees' loyalty and professionalism, the latter are connected to their legislative experience. With regards to high-policy posts, the choice of nonpartisans can fulfill this qualification. Nonpartisan ministers are most likely to be experts in their fields. In Korean cabinets, more than 80 percent of nonpartisan ministers are career civil servants or professors (Hahm, Jung, and Lee Reference Hahm, Jung and Lee2013; Lee Reference Lee2018b). Nonpartisans are also easier to control because their appointments and dismissals are not tied to the cabinet's legislative support (Dowding and Dumont Reference Dowding, Dumont, Dowding and Dumont2009). The appointment of nonpartisans can thus provide a variety of advantages for managing a president's platform in key policy areas. Therefore, my first hypothesis is the following:

Hypothesis 1:

High-policy posts are more likely to go to nonpartisan ministers than political-leverage posts.

Although nonpartisans are generally perceived to be “selected to have incentives that coincide closely with the president's goal” (Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015, 237), it is important to note the varying extent to which their political beliefs and policy preferences differ from the president's. As noted above, in the Korean context, one way to judge this ideological compatibility is whether appointees and presidents have common regional ties. Often, ministers who receive high-policy posts are selected from the president's inner circle which is formed based on such criteria as mutual biographical, educational, or familial backgrounds.Footnote 7 Thus, my second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2:

Nonpartisan ministers who have common regional ties with the president are more likely to receive high-policy posts than those who do not.

Likewise, with respect to political-leverage posts, the representation of the president's party members in the cabinet can help to fulfill the president's desire to maintain strong political leverage in the government. Scholars have argued that presidents are motivated to appoint copartisan ministers in order to strengthen the support of their own party and improve effectiveness in implementing their program (Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015; Taylor, Botero, and Crisp Reference Taylor, Botero, Crisp, Siavelis and Morgenstern2008). Specifically, by assigning political-leverage posts to their party members, presidents can connect the legislative and the executive branches while helping their copartisans to leave respectable footprints in policy making and implementation.Footnote 8 In Korean cabinets, copartisan ministers have, on average, 9.5 years of experience in the National Assembly. It is also reasonable to predict that copartisan ministers who have greater experience with the legislature are more likely to receive these posts than those who are political novices. Therefore, my third and fourth hypotheses are:

Hypothesis 3:

Political-leverage posts are more likely to go to copartisan ministers than high-policy posts.

Hypothesis 4:

Copartisan ministers with greater experience in the legislature are more likely to receive political-leverage posts than those who are not.

An evaluation of the political context in presidential democracies further suggests two additional hypotheses. As an element that shapes presidential incentives for cabinet appointments and coalition formation, the president's support in the legislature directly affects a president's political costs and benefits for appointing specific types of ministers to a post. When their party is weak in the legislature, presidents have stronger incentives to build coalitional support, and the benefit of forming a coalition can be greater. As their party becomes stronger in the legislature, however, presidents have weaker incentives to concede cabinet resources to opposition parties for coalition formation. In this case, presidents can strongly exercise their preferences over portfolio allocation, because they are not likely to pay the cost of doing so by not bringing other parties into the cabinet. This forms the basis of my fifth and six hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5:

As the president's support in the legislature increases, high-policy posts are more likely to go to nonpartisan ministers than political-leverage posts.

Hypothesis 6:

As the president's support in the legislature increases, political-leverage posts are more likely to go to copartisan ministers than high-policy posts.

Even when presidents who have weak support in the legislature are strongly motivated to form a coalition, I expect that they will give posts to members of other parties, likely in low-profile issue areas rather than key policy areas. Presidential cabinets would be irrationally organized if chief executives gave prime seats to other party members without regard to calculating the costs of doing so. In multiparty systems, small parties that cannot usually contend for the office of the chief executive are also likely to accept the proposed posts. With no better option, they are better off doing so and accessing executive resources than staying outside government and receiving nothing (Samuels Reference Samuels2002).

Data

In my empirical analysis, I test the six hypotheses presented in the previous section using an original dataset on the composition of Korean cabinets from 1988 to 2013. The dataset contains 467 observations (ministers) across five presidential administrations and updates but differs from the Korean Ministerial Database constructed by Hahm, Jung, and Lee (Reference Hahm, Jung and Lee2013) in that it includes political profiles of all ministers such as party affiliation, has information about contexts, and covers a more recent time period (2008–2013).Footnote 9 Changes in cabinet formation frequently occur during the presidential terms in Korea, and 49.3 percent of the ministers in my sample served less than a year. However, 11.3 percent of the ministers in my sample were retained within or across administrations through holding multiple positions in the cabinet.

My major dependent variables are types of ministers concerning their party affiliation. As described above, there are three types of ministers in Korean presidential cabinets: copartisan, other partisan, and nonpartisan ministers. A large majority (67.7 percent) of ministers are nonpartisan; 28.3 percent of my observations are from the president's party; and 4 percent of my observations are from legislative parties other than the president's.

My key independent variables are types of cabinet portfolios and the president's support in the legislature. As briefly discussed above, there are three types of portfolios: high-policy, political-leverage, and low-profile. First, high-policy positions involve the most important policy areas and the salient responsibilities that the chief executive has to effectively manage while in office (Pekkanen, Nyblade, and Krauss Reference Pekkanen, Nyblade and Krauss2006; Shugart, Pekkanen, and Krauss Reference Shugart, Pekkanen and Krauss2013). These policy areas concern economic management, foreign affairs, national defense, internal affairs, and legal affairs.Footnote 10 Often, these posts are occupied by career professionals from the same field.Footnote 11 In my dataset, 93.8 percent of foreign affairs ministers are former diplomats, 94.4 percent of defense ministers are former military generals, and 87.5 percent of justice ministers are former legal experts such as prosecutors, judges, or attorneys.

Second, political-leverage posts cover policy areas where organized interests exist, or where the nature of the duties requires skills to coordinate with the legislature (Park, Hahm, and Jung Reference Park, Hahm and Jung2003). To categorize specific posts into this group, I used multiple sources, including personal interviews with ministers as well as academic publications, news reports, and websites.Footnote 12 I anticipated that these posts would go to senior legislators from the president's party. Consider the example of President Kim Young-sam. In 1993, when Kim took office as the first civilian president of democratized Korea, he foresaw labor unions' strong demand for the improvement of workers' rights. Facing these expected challenges during the democratic transition period, Kim's choice of Labor Minister was Lee In-je, an incumbent legislator from his Democratic Liberal Party (DLP). Lee was a member of the Committee on Labor and Employment in the National Assembly, and he later contributed to the Kim administration by instituting a national unemployment insurance system.Footnote 13 In my dataset, 79.3 percent of Political Affairs Ministers, 50 percent of Labor Ministers, and 42.9 percent of Health and Welfare Ministers are from the president's party.

Third, low-profile positions include policy areas that are less salient and tend to be represented by dispersed interests (Pekkanen, Nyblade, and Krauss Reference Pekkanen, Nyblade and Krauss2006). I group all posts that are neither high-policy nor political-leverage into this category. When necessary, presidents would distribute these posts to coalition members in exchange for their legislative support, mainly due to the low costs of conceding the posts to members of other parties. Consider the formation of a coalition government by President Kim Dae-jung. In 1998, when Kim and his legislative party, the National Congress for New Politics (NCNP), formed a coalition with the conservative United Liberal Democrats (ULD), he allocated a part of relatively low-profile cabinet seats, including Science and Technology, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Industry and Energy, and Construction and Transportation posts, to his coalition partner.Footnote 14

Another main independent variable is the president's support in the legislature. To measure this variable, I use the size of the president's party in the legislature, which is the proportion of seats occupied by the president's party in the Korean National Assembly. In addition, for further analysis concerning ministers' backgrounds in models shown in Table 3, I include a set of variables characterizing ministers' biographical, educational, and political backgrounds: age (in years), gender (1 if ministers are female, otherwise 0), hometown (1 if ministers are from the same hometown with a president's, otherwise 0), education (1 if ministers have a bachelor's as the highest degree, 2 if ministers have a master's as the highest degree, and 3 if ministers have a doctoral degree), and legislative experience (the length of service as a member of the National Assembly in years).

I also control for five variables associated with political and economic contexts, which may affect presidential incentives for portfolio allocation. The first variable is a measure of legislative fragmentation. For this measure, I adopt the effective number of legislative parties, the index created by Laakso and Taagepera (Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979), which gives a higher value for a more fragmented legislature. Facing more fragmented legislatures, presidents may have stronger incentives to form a coalition, and they are thus more likely to concede cabinet posts to members of other parties (Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007). The second variable is a measure of the electoral cycle, which is the number of months left until the end of a president's term. I include this variable because the dynamics of cabinet politics tend to vary with the fixed electoral calendar and shift over the course of the president's term (Altman Reference Altman2000). The third variable is a measure of economic crisis. As observed during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, presidents tend to rely on the expertise of technocrats in response to economic hardship. To address this possibility, I use the monthly change in the consumer price index as a proxy measure. Note that this measure is based on the estimation of the moving average of three months before portfolios were allocated in order to smooth the monthly variation and capture its lagging impact (Amorim Neto and Strøm Reference Amorim Neto and Strøm2006; Martínez-Gallardo Reference Martínez-Gallardo2012). The fourth variable is a measure of an age of democracy, which is the number of years since the country's democratic transition. I account for this variable because new democracies with an immature party system may be “more conducive to non-partisanship in the cabinet” (Amorim Neto and Strøm Reference Amorim Neto and Strøm2006, 639). The last variable is a measure of the magnitude of cabinet reshuffling, which is the proportion of cabinet seats replaced at the time of new appointments. This variable may positively or negatively affect specific allocation patterns due to the nature of cabinet reform. All models also include a set of dummy variables for the presidential administration due to possible baseline differences in presidents' propensities for portfolio allocations. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all independent and control variables.

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of Independent and Control Variables

RESULTS

I begin my analysis by estimating the likelihood of each minister type holding three different types of posts. For this analysis, I employ multinomial logistic regression models with administration-level fixed effects. Given that there are three categories of the dependent variable that are not ordinal, multinomial logistic regression is the appropriate analytical tool. Based on my first four hypotheses, the most significant distinction in minister type is between nonpartisans and copartisans. Therefore, for the dependent variables, my baseline categories are copartisans in Models 1 and 2 and nonpartisans in Models 3 and 4. Hypothesis 1 suggests that high-policy posts should be more likely to go to nonpartisan ministers than political-leverage posts, so the coefficient on h igh-policy should be positive (Model 1). Hypothesis 3 suggests that political-leverage posts should be more likely to go to copartisan ministers than high-policy posts, so the coefficient on p olitical- leverage should be positive (Model 3). Hypotheses 5 and 6 suggest that the likelihood of high-policy and political-leverage posts being allocated to nonpartisan and copartisan ministers, respectively, should be higher with an increase in the president's support in the legislature. Therefore, I predict positive signs for the interaction term between h igh-policy and legislative support (Model 2) and the interaction term between p olitical- leverage and legislative support (Model 4). In addition, with a nonpartisan minister as the baseline category of the dependent variable in Model 5, I expect the coefficient on l ow-profile to be positive as low-profile posts should be more likely to be go to ministers of other parties than high-policy posts. Table 2 presents the results analyzing the effects of portfolio type on the likelihood of being allocated to the three types of ministers. Specific results are discussed below.

Table 2 Multinomial Logit Analysis of Policy Area of Post, Political Context, and Minister Type

Note: Dependent variables: 1 if minister is nonpartisan, copartisan or other partisan.

Baseline categories: political-leverage or high-policy post, Roh Tae-woo administration. Robust standard errors clustered on administration in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

The evidence from Table 2 is consistent with my hypotheses and lends strong support for my argument that the president's portfolio allocations vary according to specific considerations concerning policy objectives. First, as suggested in Hypothesis 1, high-policy posts are significantly more likely to go to nonpartisan ministers than political-leverage posts (1.340, p < .01, Model 1). Using Clarify (Tomz, Wittenberg, and King Reference Tomz, Wittenberg and King2003), I estimate that nonpartisan ministers are 9.4 percent more likely to be assigned high-policy posts than political-leverage posts, holding all other variables constant.Footnote 15 Nonpartisan ministers are in fact the most likely to hold low-profile posts (1.688), but the margin (10.7 percent) is not considerably different.Footnote 16 Second, as suggested in Hypothesis 3, political-leverage posts are significantly more likely to go to copartisan ministers than high-policy posts (1.340, p < .01, Model 3). Substantively, copartisan ministers have a 9.7 percent higher likelihood of holding political-leverage posts than high-policy posts. In addition, the result in Model 5 indicates that low-profile posts are more likely to be assigned to ministers of other parties than high-policy posts (0.658, p < .05, 1.7 percent).

Historically, since the country's democratic transition, economic and administrative reforms have been an important part of Korean presidents' agendas. Through the recruitment of ideologically compatible professionals, cabinet appointments have positive implications for presidents who seek to accomplish responsiveness and competence in the administration. Including Kim Young-sam's adoption of major economic reforms for deregulation and privatization as the first civilian president (see Baum Reference Baum2007), Korean presidents handily delegated the delivery of policy commitments to professional ministers such as career civil servants, taking advantage of their expertise and experience in relevant policy areas. Particularly in key policy areas, such as economic management, foreign affairs, national defense, and legal affairs, presidents could expect ministers with professional backgrounds to efficiently control highly trained personnel groups in the bureaucratic organization.Footnote 17

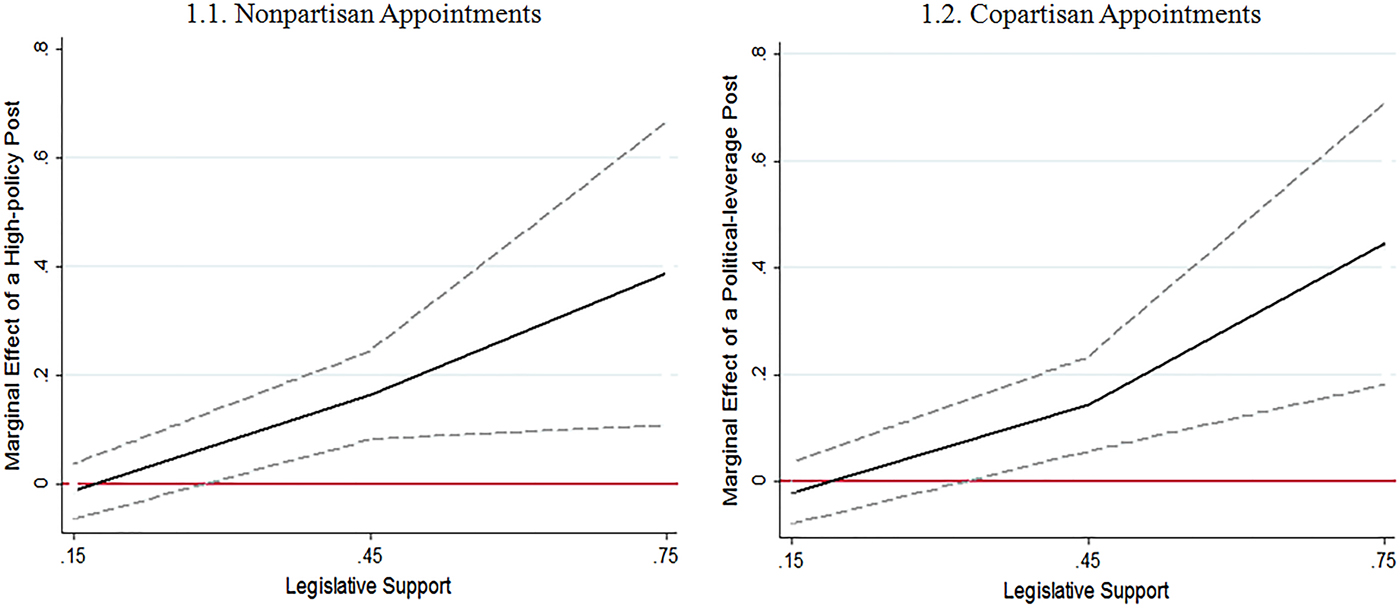

Table 2 also reports the results of how the patterns of portfolio allocation, presented in Models 1 and 3, are mediated by important political contexts such as the president's support in the legislature. In Model 2, the coefficient on the interaction term between high-policy and legislative support is positive (5.033) and statistically significant (p < .01), indicating that the likelihood of allocating high-policy vis-à-vis political-leverage posts to nonpartisan ministers becomes greater as the president's support in the legislature increases (H5). This is clearly illustrated in Figure 1 (1.1), which shows the marginal effect of a high-policy post on the predicted probability of being assigned to nonpartisans across the president's support in the legislature. Based on the estimation of Model 2, an increase in the president's support in the legislature from its observed mean to maximum values leads to a considerably increased probability of nonpartisan ministers' appointments to a high-policy post: from 21.9 percent to 38.7 percent. At the observed mean value of legislative support, nonpartisan ministers have a 21.9 percent higher likelihood of receiving a high-policy post than a political-leverage post, but this likelihood rises up to 38.7 percent at the observed maximum value of legislative support.

Figure 1 Marginal Effect of High-policy and Political-leverage Posts and Predicted Probability of Nonpartisan and Copartisan Appointments

Similarly, in Model 4, the coefficient on the interaction term between political-leverage and legislative support is positive (5.033) and significant (p < .01), indicating that the likelihood of allocating political-leverage vis-à-vis high-policy posts to copartisan ministers becomes higher as the president's support in the legislature increases (H6). The power of this interaction effect is graphically described in Figure 1 (1.2), which demonstrates the marginal effect of a political-leverage post on the predicted probability of being assigned to copartisans. Based on the estimation of Model 4, an increase in the president's legislative support from its observed mean to maximum values leads to a substantially heightened probability of copartisan ministers' appointments to a political-leverage post: from 20.7 percent to 44 percent. Copartisan ministers have a 20.7 percent higher likelihood of receiving a political-leverage post than a high-policy post at the observed mean value of legislative support, but this probability becomes as high as 44 percent at the observed maximum value of legislative support. In sum, these findings confirm that the patterns of portfolio allocation, presented in Models 1 and 3, are more likely to occur with an increase in the president's support in the legislature, because presidents can strongly exercise their preferences over portfolio allocation in such contexts.

The results of the control variables have interesting implications, but only a few of the coefficients reach statistical significance. The coefficient on legislative fragmentation is negative and statistically significant in Models 1 and 2, whereas it is positive and statistically significant in the remaining models. A more fragmented legislature clearly reduces the likelihood of nonpartisan appointments and largely enhances the probability of partisan appointments. Consistent with the literature, presidential incentives for coalition formation increase with the degree of legislative fragmentation (Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007), and copartisan appointments are also likely to increase in such context.

The results in Table 2 are based on the probability of three different types of posts being allocated to each minister type. However, the logic behind my hypotheses is more specific concerning ministers' backgrounds. Hypothesis 2 suggests that nonpartisan ministers who have common regional ties with the president should be more likely to receive high-policy posts than those who do not. Hypothesis 4 suggests that copartisan ministers with greater experience in the legislature should be more likely to receive political-leverage posts than those who are not. Therefore, I further analyze the likelihood of individual ministers with different backgrounds being appointed to specific types of posts. I use logistic regression models with administration-level fixed effects for this analysis. Table 3 presents the results of logistic regression analyzing the effects of ministers' backgrounds on the likelihood of holding two different types of portfolios: high-policy and political-leverage posts. Models 1 and 3 report all types of ministers. Models 2 and 4 include only nonpartisan and copartisan ministers, respectively.

Table 3 Logit Analysis of Ministers' Backgrounds and Policy Area of Post

Note: Dependent variables: 1 if minister holds a high-policy or a political-leverage post.

Baseline category: Roh Tae-woo administration. Robust standard errors clustered on administration in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

The evidence from Table 3 is consistent with the logic underlying Hypotheses 2 and 4. Indeed, ministers' backgrounds are a proven key consideration in the president's portfolio allocations, which is in line with existing research on ministerial appointments in Korea (Hahm, Jung, and Lee Reference Hahm, Jung and Lee2013; Park, Hahm, and Jung Reference Park, Hahm and Jung2003). First, as suggested in Hypothesis 2, nonpartisan ministers are more likely to receive a high-policy post when they share regional ties with the president. In Model 2, nonpartisans who have common regional ties with the president are more likely (by one additional percentage point) to be appointed to a high-policy post than those who do not, holding all other variables constant.Footnote 18 The coefficient on h ometown holds positive and statistically significant even among the whole set of observations (Model 1), which suggests that a shared geographical background is generally used to judge candidates' ideological propensity regarding important policy areas in the context of Korean politics. In a multi-step process where the president reviews “whether a candidate's political beliefs and policy preferences fall in the acceptable range” (Lee, Moon, and Hahm Reference Lee, Moon and Hahm2010, 82S), such cues can help presidents choose nominees whose political ideology and policy positions are compatible with theirs.

Second, the coefficient on legislative experience is positive and statistically significant in Model 3, which suggests that ministers with greater experience in the legislature are more likely to receive a political-leverage post than those who are not. Holding all other variables equal,Footnote 19 ministers have a 21.5 percent higher likelihood of holding a political-leverage post when their experience with the legislature increases from its observed mean to maximum values. The coefficient, however, remains positive but turns insignificant exclusively among a total of 132 copartisan ministers (Model 4). The results suggest that ministers with extensive legislative experience have a clear advantage for receiving a political-leverage post when compared with the overall pool of ministers, but once co-partisanship is accounted for, this advantage seems minimal. Nonetheless, this finding may not be so surprising because presidents sometimes grant this type of post to young and ambitious party members who can be future presidential candidates.Footnote 20

The results of the other background variables also have interesting implications. The coefficient on g ender is positive and statistically significant in Models 3 and 4, but it is negative and significant in Model 1. The finding that women ministers are less likely to receive key cabinet posts and more likely to hold less important posts is consistent with existing research on presidential cabinets in the Latin American context (Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson Reference Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2009). The coefficient on a ge is positive and statistically significant in Model 1 but negative and significant in Model 3. These results suggest differences in the individual characteristics of ministers who receive high-policy and political-leverage posts. Senior ministers with extensive experience in their fields are more likely to hold the former, while younger and politically ambitious ministers are more likely to hold the latter. The coefficient on e ducation is negative and statistically significant in Models 1 and 2. Appointees' academic training and knowledge should be important in choosing ministers, but educational qualifications may not be a top priority in assigning key cabinet posts. While the control variables such as electoral cycle, economic crisis, and age of democracy also seem to be negatively associated with the likelihood of portfolio assignments, these variables perform inconsistently across model specifications.

CONCLUSION

The president's calculations in achieving policy goals are central to the allocation of cabinet portfolios in presidential systems. In this article, I have demonstrated how the distribution of cabinet appointments is systematically affected by presidential incentives to accomplish their goals in the government: Korean presidents are strategic in their assignment of posts, treating ministers differently based on their party affiliation. Presidents allocate positions in key policy areas to ideologically compatible nonpartisan professionals in an effort to keep their promises to the public in such issue areas, but they also reserve seats for their party members, so that these politicians can exert legislative influence on their behalf. This allows presidents not only to promote the government's general reputation through the delivery of their important policy commitments as national leaders, but also, as heads of government and party leaders, to shore up the cabinet's legislative support and grease the wheels in the governing process.

Moreover, my findings also suggest that portfolio allocation responds to the incentives of crucial political contexts such as the president's support in the legislature. As demonstrated in previous studies (Amorim Neto Reference Amorim Neto2006; Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007, Cox and Morgenstern Reference Cox and Morgenstern2001; Shugart and Mainwaring Reference Shugart, Mainwaring, Mainwaring and Shugart1997), legislative support from their own party becomes an important source of institutional leverage for presidents in the policy making and cabinet appointment processes. When their party gains legislative seats, presidents can afford to strongly exert their preferences over portfolio allocation, and we are thus more likely to observe the distinct patterns of portfolio allocation to nonpartisans and copartisans, as described above. Beyond simply observing that particular categories of executive offices are disproportionately allocated to ministers based on their partisanship, we see that presidents structure their distribution of cabinet posts, adjusting to various political contexts.

My findings on portfolio allocation speak to the recent literature on the effects of the institutional separation of powers and provide new evidence about the behavioral aspect of cabinet formation. The comparative research on cabinet formation in presidential systems acknowledges policy making incentives as main drives to practice different appointment strategies (Amorim Neto Reference Amorim Neto2006; Cheibub Reference Cheibub2007, Geddes Reference Geddes1994; Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015). Yet, how ministers are selected to fill certain cabinet posts depending on their partisanship, and the way these patterns reflect different forms of governing incentives, are largely overlooked. I show that the observed patterns of portfolio allocation mirror presidential efforts to achieve their policy goals given a trade-off they face under the institutional separation of powers.

These patterns highlight the difference from portfolio allocations in parliamentary systems, particularly to the chief executive's party members. In parliamentary democracies where the incentive of appointing copartisan ministers is compatible with parliamentarians' aim (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010), electoral incentives matter considerably in post allocation. The ruling party's electoral success should thus be central to the allocation of ministerial portfolios in parliamentary systems. Typically, key policy posts go to the most senior and secure parliamentary members from the ruling party, who then may focus on developing and maintaining a strong party label (Pekkanen, Nyblade, and Krauss Reference Pekkanen, Nyblade and Krauss2006). In contrast, in presidential democracies, these posts can be assigned to a president's most reliable agents even at the expense of the importance of their party organization.

In analyzing the systematic relationship between ministers and portfolio types, future work should seek to expand the period of observation as well as the number of cases in order to understand the impact of institutional factors such as party system institutionalization, constitutional powers, and term limits on the patterns of portfolio allocation, particularly in key policy areas.Footnote 21 Recent research casts some light on the linkage between the centralization of the party organization and an increase in copartisan appointments (Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015). However, the question of whether there is any difference in portfolio allocation with the institutionalization of political parties and party systems is largely unexplored. Since party labels play a central role in providing cues about a candidate's political views in institutionalized party systems, old cleavages in young democracies, such as regionalism in Korea, will be replaced by new cleavages, represented by party organizations, as democracies mature. In such contexts, the president's party members should become more prevalent in key policy positions, as evidenced by the United States.

My analysis makes significant contributions to increasing our understanding of portfolio allocation as a policy-making strategy in South Korea. The findings have the possibility to travel beyond East Asia and also have important implications for the quality of governance and representation in young democracies. Given evidence from my analysis, further research can find out how such patterns of personnel distribution influence the kind of policies political leaders adopt and the level of accountability and responsiveness to constituents these policies represent. The fact that presidents strategically structure their portfolio allocations according to particular, institutionally driven concerns and thus adapt to variations in political contexts also suggests the important impact such contexts may have on the qualities of policy making and representation in presidential democracies.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2018.16.