1. Introduction

Recent epidemiological studies indicate a progressive increase in the overall rates of [Reference Kessler, Avenevoli and Ries Merikangas1], and decrease in the age at onset (AAO) of first major mood episodes [Reference Burke, Burke, Rae and Regier2, Reference Merikangas, Jin and He3]. Initial evidence for the earlier AAO in younger generations mostly originated from studies of depressive disorders [Reference Kovacs and Gatsonis4, Reference Wickramaratne, Weissman, Leaf and Holford5], or from community samples comprised of both unipolar and bipolar disorders [Reference Gershon, Hamovit, Guroff and Nurnberger6, Reference Wittchen, Knauper and Kessler7]. Fewer studies focused only on bipolar disorders and those that exist have applied widely differing methodologies, especially regarding sampling and analytic approaches [Reference Bauer, Glenn and Alda8–Reference Post, Kupka and Keck10]. These different approaches mean that there are some important gaps in our understanding of any observed trends in AAO. For example, some studies include self-identified cases presenting with a wide range of bipolar spectrum disorders, some include cases with prepubertal onset or paediatric bipolar disorders, whilst other studies included adults recruited via the media [Reference Post, Kupka and Keck10, Reference Chengappa, Kupfer and Frank11]. As such, there is a lack of clarity about whether any secular or temporal trends in AAO apply to rigorously defined adult-pattern bipolar disorders presenting to clinical psychiatric services rather than other heterogenous samples [Reference Gershon, Hamovit, Guroff and Nurnberger6, Reference Bauer, Glenn and Alda8, Reference Golmard, Scott and Etain9, Reference Douglas and Scott12, Reference Lasch, Weissman, Wickramaratne and Bruce13].

An area of uncertainty is whether any reduction in AAO of bipolar disorders is better explained by a period rather than a birth cohort effect [Reference Bauer, Glenn and Alda8, Reference Post, Kupka and Keck10]. For example, the findings of an earlier AAO can arise because of changes in diagnostic practice, such as the introduction of paediatric bipolar prototypes in recent birth cohorts [Reference Post, Kupka and Keck10, Reference Douglas and Scott12, Reference Bellivier, Etain and Malafosse14]. However, the influence of diagnostic trends can be counterbalanced by two strategies. First, by ensuring all cases included in a study are re-assessed and the diagnosis of the first episode is made according to contemporary, established, international classification systems irrespective of the criteria used to make the original diagnosis (e.g. applying ICD 10 and DSM IV) [Reference American Psychiatric Association15, Reference World Health Organisation16]. Second, by focusing on a narrower range of valid bipolar syndromes that can be identified with a high level of reliability, i.e. mania or bipolar-I-disorder (BD-I) [Reference First17].

Another potential issue in clinical studies of AAO is sampling bias, as age at interview can be a major confounder of any findings related to birth cohort effects [Reference Bauer, Glenn and Alda8, Reference Post, Kupka and Keck10, Reference da Silva Magalhaes, Gomes, Kunz and Kapczinski18, Reference Minnai, Tondo and Salis19]. Spurious associations may be identified between AAO and birth year because, unlike epidemiological studies, clinical studies of AAO are restricted to those patients who have developed bipolar disorder [Reference Golmard, Scott and Etain9]. As such, the participants with an early age at interview de facto can only belong to a sub-population with an early AAO. This problem can be overcome by selecting a large subsample of individuals who have all passed through the full age range for risk of onset of bipolar disorders. However, this cannot always be achieved, especially if the original unselected sample is relatively small; and it is notable that the median sample size was <1000 in the five clinical studies of birth cohort effects on AAO of bipolar disorders [Reference Bauer, Glenn and Alda8–Reference Chengappa, Kupfer and Frank11, Reference da Silva Magalhaes, Gomes, Kunz and Kapczinski18].

If a birth cohort effect can be demonstrated in a clinical sample, then it is important also to determine whether differential exposure to risk factors has precipitated earlier expression of an underlying vulnerability in individuals born in recent decades. For example, Post and colleagues [Reference Post, Kupka and Keck10] have identified that an earlier AAO of bipolar disorders is associated with childhood exposure to trauma, especially in those with a higher familial loading for bipolar disorders. It is also important to identify modifiable risk factors that occur more often in adolescence and adulthood rather than childhood [Reference Eaton, Tsuang and Zahner20]. One such factor, identified in epidemiological and clinical studies and in meta-analyses, is the presence of an alcohol and/or substance use disorder (ASUD); and it is hypothesized that this could be associated with a decrease in the AAO of mania in individuals who are predisposed to developing bipolar disorders [Reference Minnai, Tondo and Salis19, Reference Di Florio, Craddock and van den Bree21–Reference Stone, Fisher and Major24].

This study addresses important gaps in our knowledge of birth cohort effects on AAO of bipolar disorders by examining AAO distributions in a large, clinically representative European sample of adult patients with a reliably ascertained diagnosis of BD-I. The study employs statistical approaches to the AAO analyses that try to minimize any period, sampling and age-related biases and aims to establish:

(a) if there is evidence for changes in AAO of BD-I in cases categorized according to birth decade

(b) whether the observed AAO distributions differ according to sex and/or exposure to ASUD.

2. Methods

2.1 Sample

The study uses data from two large-scale studies; the first recruited individuals from four clinical centres in France and Switzerland (Paris, Bordeaux, Nancy and Geneva) [Reference Bellivier, Etain and Malafosse14, Reference Etain, Lajnef and Bellivier25] and the second recruited individuals from 14 countries (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and UK) to the European Mania in Bipolar Longitudinal Evaluation of Medication study (EMBLEM) [Reference Tohen, Vieta, Gonzalez-Pinto, Reed and Lin26]. The studies were chosen as they had similar recruitment and sampling strategies, the populations were of similar age study entry, they employed comparable methodologies including the use of face-to-face interview and case note assessments undertaken by trained clinicians who were blinded to the hypotheses being tested, and previous publications from the combined dataset have been subjected to peer-review [Reference Golmard, Scott and Etain9, Reference Bellivier, Etain and Malafosse14]. For both multi-national studies, ethical approval for each clinical centre was obtained locally, and it permitted the creation of databases containing de-identified clinical information from study participants aged > = 18 years.

2.2 Assessments

Full details of the methodologies are reported elsewhere [Reference Golmard, Scott and Etain9, Reference Bellivier, Etain and Malafosse14]. To briefly summarize, consecutive adult psychiatry referrals with a probable diagnosis of bipolar disorder that gave written informed consent, were interviewed by study psychiatrists (between 1993 and 2008). Using structured clinical assessments, information on sex, date of birth, and age at interview was recorded alongside an evaluation of the psychiatric history, including details of: (a) BD-I diagnosed according to internationally recognised criteria (i.e. ICD 10 or DSM IV) [Reference American Psychiatric Association15, Reference World Health Organisation16]; (b) ASUD (recorded as the presence or absence of a diagnosis of alcohol and/or substance abuse or dependence diagnosed according to internationally recognised criteria); and (c) the AAO of BD-I, which was operationalized as the age at which the patient could first be reliably diagnosed with a major mood episode verified by data from the structured clinical interview, independent records (e.g. blinded reviews of clinical case notes), and other valid sources of information (e.g. informants, etc). Although this AAO estimate relies on retrospective assessments, the method has a high reliability for BD-I (r = 0.89) [Reference Egeland, Blumenthal, Nee, Sharpe and Endicott27] and has been widely used in research over recent decades [Reference Bellivier, Golmard and Rietschel28–Reference Suppes, Leverich and Keck30].

2.3 Statistical analyses

Preliminary data checking confirmed that the two samples were comparable on the key study variables; there were no significant differences in mean AAO of BD-I (p = 0.16), the ratio of male to female cases (p = 0.75), or the prevalence of ASUD (p = 0.32). As such, we merged the datasets for the sub-set of five key variables of interest: date of birth, age at baseline interview, AAO of BD-I, sex and ASUD status. We then excluded cases born in decades <1930 or >1970 (due to the small number of eligible cases in these subgroups), so the final sample comprised of 3896 cases (3140 from the EMBLEM database; 736 from the French/Swiss database).

2.3.1 Description of AAO distributions in the total (unselected) sample

We derived cumulative probabilities for being diagnosed with BD-I as a function of age for cases born in four decades (1930s to 1960s). As all individuals included in the analyses have the disorder being studied, these probability curves represent AAO distributions for consecutively recruited BD-I cases, not life time risk of disorder (for a discussion of the rationale for this methodology and its application to mood disorders see Kovacs et al. [Reference Kovacs and Gatsonis4]). The AAO distributions for each birth cohort were compared with those for the selected sub-sample (see below) to ensure that the sub-sample was representative of the total sample.

2.3.2 Planned analyses in the selected sub-sample

The dependent variable in our analyses was AAO of BD-I and the main independent variable was decade of birth. However, it is recognized that there is a significant correlation between AAO and age at assessment interview in samples of consecutively recruited patients, i.e. AAO and age at interview are inter-dependent (especially in cases from more recent birth cohorts) [Reference Bellivier, Etain and Malafosse14]. To minimise the confounding effects of age at interview, we determined empirically that cases aged > = 50 years at study entry could be included in the subsample for the main analyses. As shown in the Supplementary materials (Appendix 1), this represents the age at which the correlation is no longer significant between AAO and birth year after controlling for age at interview.

The statistical analyses were determined a priori and were undertaken only in the subsample selected to minimize confounding. We present the cumulative probability curves and median AAO of BD-I according to sex and decade or birth (1930s, 1940s, and 1950s), and according to ASUD status (categorized as ‘without’ or ‘with’ an ASUD) for each birth cohort. We compare median AAO (reported to the nearest whole number along with the inter-quartile range (IQR)) according to birth decade, sex and ASUD status. We used Mantel-Cox log Rank (X2) tests of equality of AAO distributions (adjusted for covariates as appropriate) across birth decades, alongside pair-wise comparisons to test differences within each birth decade. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for any associations between sex, ASUD, decade of birth and AAO. Using a step-wise regression model, we examined independent effects on AAO and any interactions between sex, ASUD, decade of birth (reported as adjusted OR).

3. Results

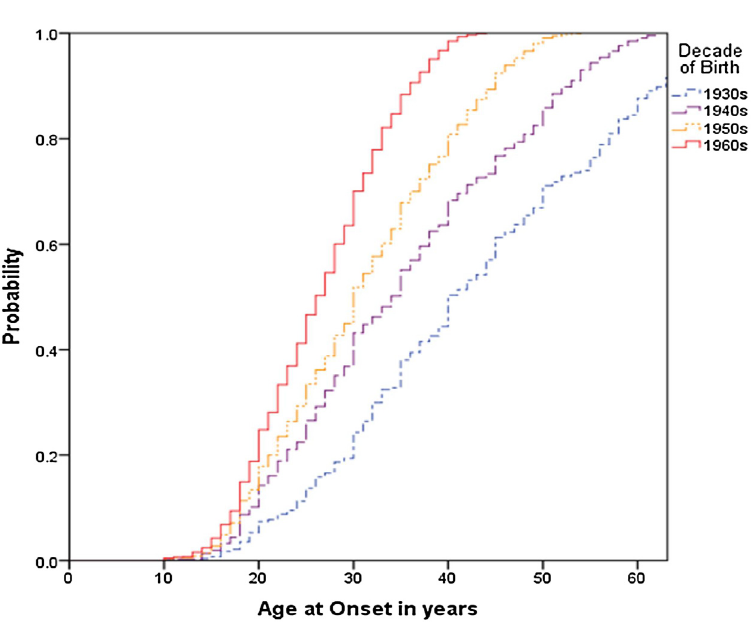

The 3896 BD-I cases comprised of 1731 males (44%) and 2165 females. The sample mean age at interview (±SD) was 44 ± 13.3 years, the mean AAO of BD-I was 29.5 ± 11.2 years and the mean duration of illness was 14.6 ± 11.3 years. About 30% of cases (N = 1207) had an ASUD, of which about two thirds were identified as AUD without another SUD (AUD alone = 21% of the total sample). Fig. 1 shows AAO distributions for the total sample; as can be seen, the median AAO was about 41 years for those born in the 1930s, about 34 years for those born in the 1940s, about 30 years for those born in the1950s and about 26 years for those born in the 1960s.

Fig 1. Age at onset of bipolar I disorder in cohorts defined according to decade of birth (total sample, unadjusted for age at interview).

The selected sub-sample of 1274 cases comprised of 519 (41%) males and 755 females. There were 386 individuals born in the 1930s (Males = 154; 40%), 657 individuals born in the 1940s (Males = 274; 42%) and 231 born in the 1950s (Males = 91; 40%). The median AAO for each birth cohort decreased from 41 years (IQR: 30–56) for the 1930 cohort, to 34 years (IQR: 24–45) for the 1940 cohort, to 31 years (IQR: 25–44) for the 1950 cohort (OR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.51,0.81). Overall, the AAO findings in the selected subsample reflected those reported in the total sample.

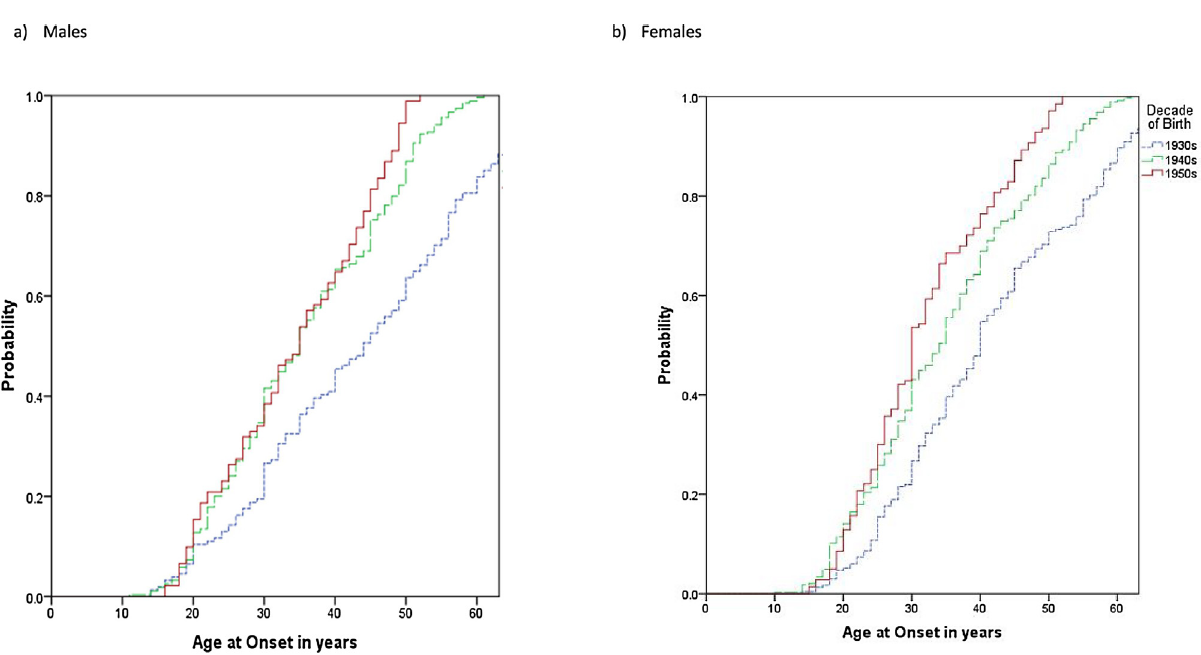

Fig. 2 shows AAO distributions by sex, without adjustment for ASUD. The median AAO in each birth cohort decreased in females from 40 to 33 to 30 years for consecutive birth cohorts (log-rank tests: 1930s to 1940s: p < 0.001; 1940s to 1950s: p < 0.001). In male cohorts, the median AAO decreased from 43 to 32 years (1930s to 1940s: p < 0.001; 1940s to 1950s: p < 0.03). Although AAO was slightly younger in each female birth cohort compared to each male birth cohort, the decrease in AAO for consecutive birth cohorts was not significantly different (OR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.69, 1.11).

Fig 2. Age at onset of bipolar I disorder in males and females for cohorts defined according to decade of birth.

The prevalence of ASUD in females increased significantly from 10% of cases born in the 1930s to 29% of cases born in the 1950s (X2 = 22.29; df 2; p = 0.001). In males, the prevalence of ASUD in consecutive cohorts increased from 22% to 39% (X2 = 7.03; df 2; p = 0.03). In both sexes, there was a non-significant trend for a greater increase in ASUD and SUD compared to AUD alone (data not shown).

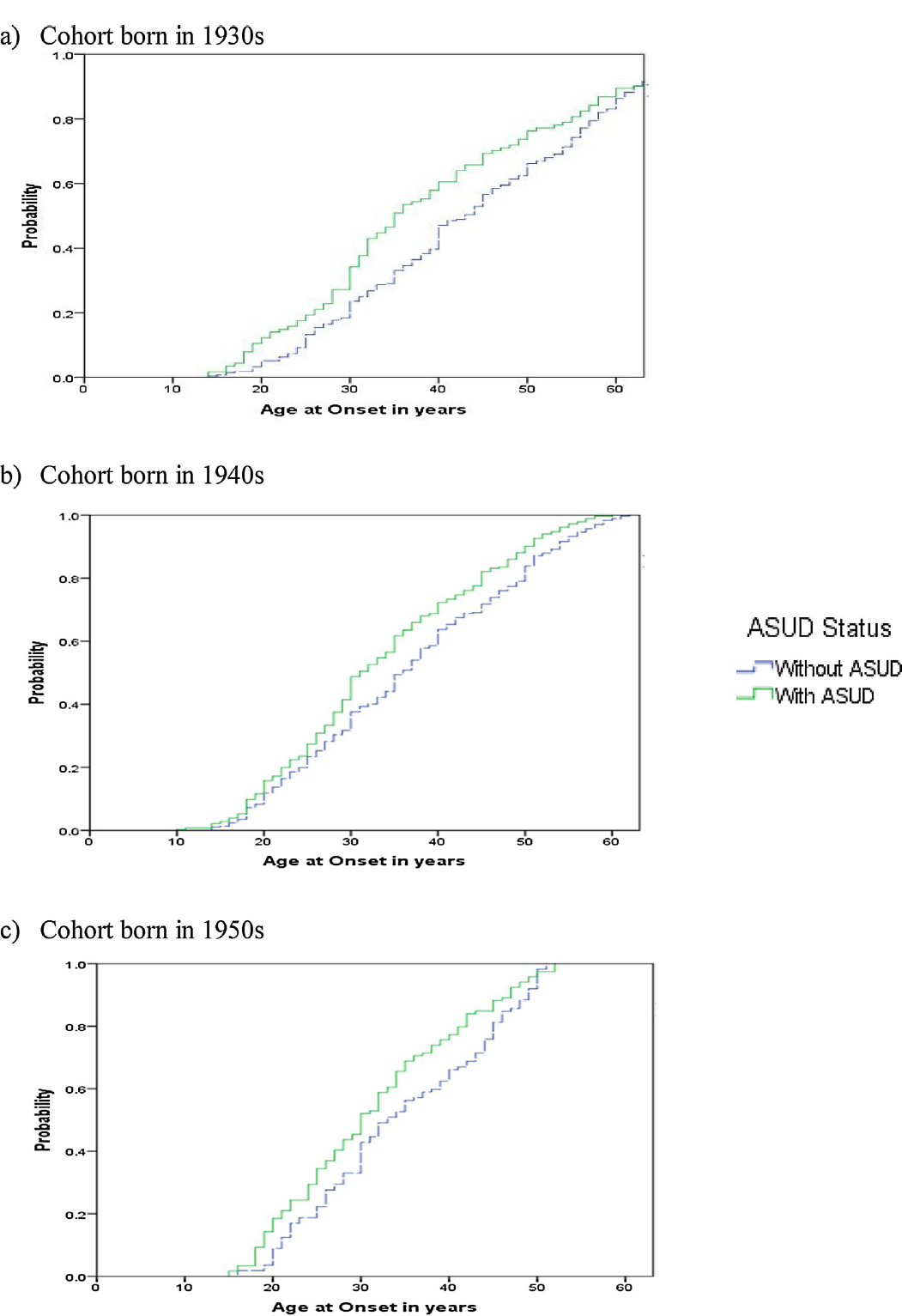

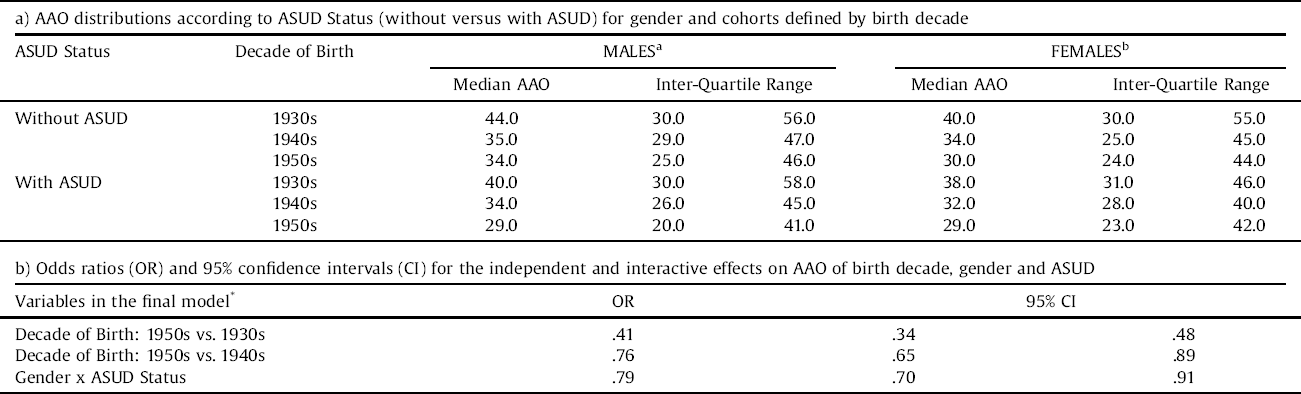

Fig. 3 shows that the median AAO for each birth cohort was earlier in cases with an ASUD as compared to those without an ASUD (OR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.69, 0.87), whilst Table 1 a highlights that males demonstrate an earlier median AAO in each consecutive cohort. Furthermore, within each birth decade, the AAO is always earlier in males with an ASUD compared to those without an ASUD. In females, the pattern is very similar except that the AAO does not differ according to ASUD status in the cohort born in the 1950s.

Fig 3. Age at onset of bipolar I disorder in individuals without or with a history of alcohol and/or substance use disorder (ASUD) in cohorts defined according to decade of birth.

Table 1b reports the final stepwise regression model for the effects on AAO of birth cohort, sex and ASUD. The adjusted OR demonstrate that there is a significant, independent effect of birth cohort on AAO (1950s versus 1930s: OR: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.34, 0.48; 1950s versus 1940s: OR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.65, 0.89) and an interaction between ASUD status and sex, with males with an ASUD in each birth cohort having a significantly lower AAO (OR: 0.79: 95% CI: 0.70, 0.91).

Table 1 Analysis of age at onset (AAO) distributions according to gender, birth decade and ASUD status (without versus with an alcohol and/or substance use disorder).

a,bMantel-Cox log rank tests and pairwise comparisons for equality of AAO distributions for cases without versus with an ASUD and according to birth decade.

aMales: X2 = 14.74; p < 0.001; all pairwise comparisons of cases with/without ASUD within each birth decade are significant (p < 0.05).

bFemales: X2 = 23.61; p < 0.001; pairwise comparisons significant within 1930s & 1940s cohorts only (p < 0.05).

*Cox regression analysis using backward stepwise model.

REFERENCES categories: Decade of Birth = 1950s; Gender = Male; ASUD Status = with ASUD.

4. Discussion

This study utilized data from clinical cases recruited from across Europe representing the most severe end of the bipolar spectrum i.e. treated patients meeting internationally agreed diagnostic criteria for BD-I. Our specific findings are that (i) there is a significant decrease in AAO of BD-I in successive birth cohorts, and that an earlier AAO is demonstrated in both males and females; (ii) there is a secular increase in rates of ASUD in each birth cohort in both males and females; (iii) the change in AAO distributions in more recent birth cohorts also shows an association with exposure to an ASUD, (iv) that males with an ASUD born in successive birth decades consistently show an earlier median AAO than males without an ASUD, and (v) in females, the difference in AAO in those with an ASUD compared to without an ASUD peaked in the cohort born in the 1940s, but was more marginal for those born in the most recent decade under study.

It is useful to consider our findings not only in comparison to other studies, but also in the context of the strengths and limitations of the current methodology. First, in the total sample and in a sub-sample, we confirmed reports of a decrease in the AAO of bipolar disorders in recent birth decades [Reference Bauer, Glenn and Alda8–Reference Chengappa, Kupfer and Frank11, Reference da Silva Magalhaes, Gomes, Kunz and Kapczinski18] and demonstrated this occurs in samples comprised only of BD-I cases. Second, our use of a large pan-European sample gives us confidence that our findings are likely to generalize across centres and countries, which has not always been possible to demonstrate [Reference Chengappa, Kupfer and Frank11, Reference da Silva Magalhaes, Gomes, Kunz and Kapczinski18]. Third, this is one of the two largest clinical studies of this issue to date, and one of the few to both address and minimise confounding due to age at interview, etc [Reference Bauer, Glenn and Alda8, Reference Golmard, Scott and Etain9]. Fourth, measurement error was reduced by using an established approach to assess AAO, and focusing on the BD-I diagnosis (one of the three most reliable diagnoses within psychiatry) [Reference First17]. However, the study limitations include the fact that, despite the sample size, we could not realistically examine separately any effects of AUD or SUD. Nor could we explore trends in the types of substances being used (e.g. shifts between barbiturates, amphetamines and cannabis) and whether their impact varies across birth cohorts. This is likely to be important as several studies highlight that there may be differential effects of alcohol and illicit drugs, as well as sex differences in the patterns of their use [Reference Di Florio, Craddock and van den Bree21, Reference Nesvag, Knudsen and Bakken31, Reference Holtzman, Miller and Hooshmand32]. Also, the retrospective ascertainment of AAO is open to recall bias, even though we used methodologies that minimized this problem [Reference Chengappa, Kupfer and Frank11] and reduced variance across the sample [Reference Warshaw, Klerman and Lavori33]. The study datasets primarily collated clinical data and did not address life events and experiences that occurred in childhood. As such, this study cannot address whether childhood factors (such as a history of abuse) which have been shown to be associated with earlier AAO of BD are more common in those individuals who develop ASUD. Future research will need to examine pathways linking early experiences, ASUD and AAO of BD, to determine whether childhood risk factors have direct or indirect effects on AAO. A composite picture of events and experiences might help to elucidate the differences observed in males and females [Reference Post, Kupka and Keck10, Reference Douglas and Scott12, Reference Minnai, Tondo and Salis19]. Also, this did not address other factors that might be associated with decreases in AAO as well as ASUD, these might extend from demographics (unemployment), other major life events preceding illness onset, or physical and mental comorbidities. Whilst all of these could contribute to AAO and to sex differences, it is not yet known which are likely to also demonstrate secular trends.

Assuming our findings are valid, then it is worthwhile considering some of the explanations for the general effect of birth decade on AAO and any additional specific ASUD effect, as this will indicate areas for further research. A reduction in AAO could signify genetic anticipation [Reference Post, Kupka and Keck10] and, although genetic change does not usually operate with such rapidity [Reference Golmard, Scott and Etain9], future research could explore whether the birth cohort effect is more representative of gene-environment interactions [Reference Golmard, Scott and Etain9]. Regarding the latter, it would help to study whether an ASUD acts as a precursor to the onset of BD-I, or whether a shared genetic vulnerability for BD-I and ASUD increases the likelihood of earlier onset of BD-I [Reference Di Florio, Craddock and van den Bree21, Reference Etain, Lajnef and Bellivier25]. Also, it would be important to identify whether there are any sex-specific effects; these might explain our findings in males compared to females [Reference Holtzman, Miller and Hooshmand32], or could clarify whether they were a consequence of the smaller subsample analysed in later birth cohorts.

It is possible that the finding of an additional effect of ASUD on AAO in a clinical sample is an artefact or indirect effect of the added complexity and severity of the presentation (leading to these patients coming to the attention of health services). For example, data from Norway identified that the presence of an ASUD was associated with a shorter of duration of untreated bipolar disorder compared to the absence of an ASUD [Reference Kvitland, Ringen and Aminoff34, Reference Lagerberg, Larsson and Sundet35]. Lastly, further research is required to explore whether changing patterns of alcohol and substance use, albeit not meeting criteria for an ASUD, are also associated with ‘brought forward time’ in the onset of BD-I [Reference Arias, Szerman and Vega36]. This knowledge would be especially useful as it might enhance efforts to prevent or intervene early with ASUD if it were demonstrated that this might also modify the onset and course of BD-I.

5. Conclusions

We identified a secular decrease in the AAO of BD-I in both male and female patients included in a pan-European clinical representative sample and found that the birth cohort effect on AAO was associated with secular increase in rates of a potentially modifiable risk factor, namely ASUD, across each birth cohort. The association between ASUD and AAO was more robust for males than females, suggesting that other factors may be especially relevant in the latter. However, it is acknowledged that clinical studies of birth cohort effects are not directly comparable to epidemiological studies. As such, the magnitude of risk associated with ASUD or the interaction between sex and ASUD status could be decreased or fail to generalize across clinical and community settings.

Declarations

This research was supported by grants from Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (CRC 94232), ministère de la recherche (PHRC, AOM98152), Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM>) and Swiss National Science Foundation (grants 32-40677.94 and 32-049746.96).

JS is a visiting professor at Diderot University. JS has received grant funding from the Medical Research Council UK (including the ABC cohort study of bipolar II disorders) and from the Research for Patient Benefit programme UK (PB-PG-0609-16166: Early identification and intervention in young people at risk of mood disorders).

JMA has received grants/research support, consulting fees and honoraria within the last three years from Allergan, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier, Takeda and Teva.

BE- no declarations relevant to this submission.

FB has received honoraria or research or educational conference grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Otsuka, Eli Lilly & Co., Servier, Takeda, Sanofi Aventis, Lundbeck, AstraZeneca, the European Space Agency and has received peer review research funding from French Ministry of research, Assistance Publique − Hôpitaux de Paris, the National Institute for Research (INSERM) and the NARSAD.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for being granted access to the ‘French-Swiss database’ (created by researchers in both countries). We also acknowledge our thanks for being given access to the EMBLEM (European Mania in Bipolar Longitudinal Evaluation of Medication) database, which was created from a study supported by Eli Lilly and Company. The pharma company played no part whatsoever in the present study; the listed authors are independent investigators who developed the hypotheses, undertook the study and wrote the manuscript.

Appendix A Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.04.002.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.