1. INTRODUCTION

As a result of many decades of scholarship, we have a sophisticated understanding of the demography and epidemiology of England's population history since the 1540s. However, there seems to have been no attempt as yet to incorporate the history of venereal diseases into our detailed accounts of the population's demographic or epidemiological history.Footnote 1 There is no mention of venereal disease in England in the three most substantial works of demographic history: by Tony Wrigley and Roger Schofield and by Wrigley et al. on the early modern period; and by Robert Woods on the nineteenth century; nor is there a mention of it in Peter Laslett's Family life and illicit love.Footnote 2 As a recorded cause of death, syphilis was included in Thomas McKeown's tabulation of epidemiological change in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but it was never discussed, nor its incidence analysed.Footnote 3 The two most substantial early modern epidemiological studies, including one focused on London, do not attempt its study.Footnote 4

Of course, there is an excellent methodological reason for this absence of attention. Both demographic and epidemiological history are dependent on identifying satisfactory quantifiable data with which to form plausible estimates of vital rates and of disease prevalence in the past. Clearly, there is a very significant problem in this respect with the venereal diseases. Typically only syphilis actually caused a recordable vital event, which was death. However, the physiological pathways leading to a fatality are so diverse, obscure and long-acting, typically occurring many years after original infection, that the extent of the disease's capacity to cause premature mortality was not fully understood until the twentieth century.Footnote 5 Hence, deaths recorded from ‘syphilis’ in the Victorian vital registration system were relatively few and confined mainly to pauper infants in fact, where they recorded, to some extent, the effects of in utero transmission of syphilis (the etiology of this apparently ‘congenital’ syphilis was equally mystifying to contemporaries).Footnote 6 Similarly the ability of the usually non-fatal venereal diseases of gonorrhoea and chlamydia to cause both female and male infertility was not fully appreciated until the late nineteenth and later twentieth centuries, respectively.Footnote 7 Demographic historians are used to working with various forms of incomplete data but in relation to the venereal diseases this problem has presented particular difficulties.

Nevertheless, we do know from a host of less quantifiable sources studied by historians of medicine, culture, art and society that the venereal diseases afflicted British and European populations extensively, though variously, throughout the early modern and modern periods.Footnote 8 However, it was never simply an affliction of bohemian literary and artistic figures, soldiers, prostitutes, aristocratic rakes, exploited servants and tragically-wronged wives; nor is its epidemiological impact accurately captured by the cultural history of its interpretation and negotiation, the medical history of venereology, the changing scientific knowledge of the disease and its eventual control through public health policies in the twentieth century. These are all valuable contributions to our knowledge and to our appreciation of the historical importance of the venereal diseases; but they only point all the more significantly to the problem of this absolute lacuna in our knowledge of the epidemiological history of venereal disease, especially throughout the period of most dynamic change in Britain's population history, c. 1750–1914, when both fertility and mortality were subject to sweeping and locally diverse secular changes back and forth.

One set of such estimates for the latter end of this period has been recently published for the population of England and Wales in 1911–1912, as shown in Table 1.Footnote 9 These estimates were created through secondary reanalysis of evidence drawn from Wassermann tests of samples of the British population originally presented to the Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases of 1913–1916. This was the official enquiry from whose conclusions there emerged a revolutionary strategy of comprehensive, publicly-funded treatment for syphilis.Footnote 10 As a result of that early precursor of a national health service, the venereal diseases in Britain entered a new era after 1916 in which their incidence was increasingly influenced by the relative medical effectiveness of this new system of treatment.Footnote 11

Table 1 Estimates of the accumulated chance of syphilis infection among men aged in their mid-thirties in England and Wales in 1911–1912 in four categories of place

Source: S. Szreter, ‘The prevalence of syphilis in England and Wales on the eve of the Great War: re-visiting the estimates of the Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases 1913–1916’, Social History of Medicine 27, 3 (2014), 508–29, Table 3.

How do these figures for 1911–1912 compare? Was the population more or less afflicted with syphilis infection in earlier periods? Kevin Siena's highly important revisionist study of institutional treatment for venereal distempers in London from 1600 to 1800 has presented us with the most substantial body of relevant evidence from an earlier period so far assembled. He has shown that those suffering from the malady were not refused entry by the capital's charitable hospitals, as had been previously supposed, and that there was also an expanding provision for ‘foul’ patients in workhouse infirmaries throughout the eighteenth century. However, while he was prepared to conclude that ‘Venereal disease seems absolutely endemic in early modern London’, Siena did not attempt to quantify the disease's incidence.Footnote 12 He correctly pointed out that ‘We can never know what proportion of “foul” patients would today be diagnosed as “syphilitics”.’Footnote 13 But the fact that we can never know in a determinist and certain sense, does not mean that we cannot or should not use the rich evidence that is available from the eighteenth century to form useful comparative estimates of the disease's incidence at that time, provided we respect and explicitly allow for historic variance in diagnosis, deploy the most rigorous methodology available, and always retain our critical self-awareness that the results must remain estimates.

The current article will now present research aimed at constructing such comparable estimates of the accumulated chance of having been infected with syphilis by age 35 in one principal provincial city, Chester, and also its neighbouring rural region in England and Wales during the 1770s. The choice of Chester, rather than London, for an initial exercise in creating comparative estimates for this period is determined by the availability and survival of two key primary sources, which, in combination, can provide the evidence needed for the most rigorous methodology required to determine the age-specific numerators and denominators to calculate accurately the relevant rates of infection in those populations at that time.

The first of these two vital primary sources are the surviving volumes of the Chester Infirmary's Journal of patients, the hospital's admissions register. Footnote 14 The Chester Infirmary (CI), like many of Britain's provincial hospitals, was founded in the mid-eighteenth century (1755) as a voluntary subscription hospital.Footnote 15 It moved to a purpose-built site in 1761. Its surviving admissions registers contain complete and detailed information on all patients admitted as both in- and outpatients for the three consecutive years, 1773, 1774 and 1775. There is also some information on other years down to 1792, although none appears to have survived in a form as full and complete as for these three years.

The information recorded for each patient in the Journal comprised the following:

-

hospital admission ID number

-

exact date of admission

-

first and last names (giving information on sex)

-

name of the recommender

-

in- or outpatient

-

age of the patient in years

-

parish of residence in Chester (or town/village if from outside Chester)

-

physician in charge

-

how long ill before admission to the hospital

-

what ‘distemper’ (disease) was diagnosed

-

date of discharge

-

reason for discharge

The records of the Journal make it possible to count the number of Chester residents of each sex and in each five-year age group from 15 to 34 diagnosed with a ‘venereal distemper’ during these three years, 1773–1775. Secondly, Dr John Haygarth, the city's most eminent medical practitioner, who held a post at the new Chester Infirmary from 1766 until 1798, conducted a pioneering census survey of the population of Chester in 1774.Footnote 16 This crucial second primary source is superior to any such demographic source for London during this decade. It makes possible a reasonably precise reconstruction of the age structure of the numbers of the ‘at risk’ population in each five-year age group for each sex in the city in 1774. With these exactly contemporaneous two sources, the CI admissions register and Haygarth's census survey, we can therefore construct both numerators and denominators with which to calculate high quality estimates of the percentage of the population who had been treated for the pox in Chester Infirmary before the age of 35.

2. THE NUMERATORS: THE CHESTER INFIRMARY ADMISSIONS REGISTER 1773–1775

Using the evidence from the admissions registers for all three years, centred on the year of the census, 1774, there was a total of 177 admitted cases diagnosed as ‘venereal’.Footnote 17 There are in fact 174 useable cases (the three removed from analysis comprised two cases with no parish information entered; and one infant aged one admitted with both parents). To relate these 174 cases to the resident population of the city of Chester requires a considerable number of further modifications. The first group that have to be excluded from consideration are those patients recorded as residents outside the ten parishes of Chester city.Footnote 18 As many as 65 venereal patients, slightly over one third, came from outside Chester (including three soldiers).Footnote 19 Most were from towns and villages in Cheshire, with a number from North Wales and one or two from even further afield. Some of these cases will form the basis for an important supplementary exercise in the last part of this article but initially they are removed so that rates for the Chester city population can be estimated.

It is the aim of this exercise to form an estimate of the rates of treatment for the pox, in particular, rather than for all venereal conditions. To attempt to interrogate the historical primary sources to measure quantitatively the incidence of all venereal diseases in general and without discrimination would be an impossible task, since both lay and medical recognition of the various conditions and their diverse symptoms has varied so much.Footnote 20 Furthermore, both gonorrhoea and chlamydia are frequently asymptomatic (and of course the latter was entirely unrecognised by medical science before the mid-twentieth century).Footnote 21 However, syphilis, which is due to the invasion of the body by the bacterial spirochaete, Treponema pallidum, is almost never asymptomatic and also produces, during its secondary phase, a set of more prolonged and incapacitating symptoms than any of the other principal venereal diseases, such as gonorrhoea, soft chancre and chlamydia. These characteristics mean that there is a much greater possibility for tracking in the infirmary records of the eighteenth century the incidence of this specific disease entity, since it elicited a distinctive perception of its seriousness – the distinct condition that contemporaries called the pox – both among sufferers and the medical profession. It is also extremely relevant that the pox was widely considered throughout Britain at this time, the late eighteenth century, to be curable through subjection to a particular course of treatment, the mercury cure.

It is not necessary for the success of this estimation exercise for any presumption to be made about the constancy over time of diagnosis or even of the meaning of the disease to patients or practitioners – clearly this has been subject to great variation. While some physicians and surgeons in the late eighteenth century were persuaded that syphilis and gonorrhoea, known at the time respectively as ‘the pox’ and ‘the clap’ (and various other terms such as ‘running of the reins’), were distinct diseases with separate causes and symptoms, it was more widely believed that the clap and the pox represented different stages and manifestations of a single disease entity.Footnote 22 Consequently, a proportion of those initially being institutionally treated for venereal complaints would have been suffering from a range of non-syphilitic conditions, notably including gonorrhoea. There is no direct evidence available on what this proportion may have been in Chester (apart from two cases of women in their forties where ‘Fluor Albus’ was specified as their ‘distemper’).Footnote 23

Whether doctors believed that pox was a separate disease from clap or a more virulent stage of a single disease, it was predominantly those who were in fact suffering from the condition that we would today recognise as syphilis who would have been perceived, both by themselves and by their medical attendants, as requiring the more protracted and expensive standard treatment prescribed at this time for ‘the pox’, which was a course of mercurial salivation. In the 1770s the mercury treatment was widely believed to be extremely effective, albeit arduous for the patient.Footnote 24 It was credited as one of the few success stories of medicine. Thus, according to Guenther Risse in his classic study of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, ‘patients affected with venereal disease were welcome subjects for treatment, since practitioners were convinced that their medications could actually cure the ailment, a claim not easily made for most other diseases prevalent at that time.’Footnote 25 As John Haygarth himself put it after several decades of medical practice in Chester, ‘Except Mercury in the Syphilis, there are few or perhaps no examples where a remedy can produce such speedy relief and perfect recovery in so formidable a disease.’Footnote 26 Hence, we find that virtually all patients diagnosed with a venereal ‘distemper’ and remaining in hospital for at least 35 days (indicating they had taken the mercury cure) were confidently pronounced ‘cured’ on discharge in the CI Journal.

The treatment typically consisted of five to seven weeks of continuous supervised mercurial infusion, ingestion or injection, prompting pints of salivation per day in the patient, which was supposed to flush the venereal poisons out of the body. Side effects during treatment included swollen gums, mouth ulcers and severe halitosis; hence the mercury treatment was debilitating and required residential care.Footnote 27 Those who contracted a venereal disease hoped it was just ‘the clap’ and probably began by self-medicating and trying various quack nostrums that promised a cure without the incapacitating regime of salivation. This was the well-recorded experience at this time of James Boswell in London, who appears to have caught the clap many times, usually from liaisons with prostitutes, but was fortunate in probably having avoided the pox.Footnote 28 Those less fortunate who did have ‘the pox’ would find, if they did not already know, that the debilitating symptoms of the secondary stage of pain and fevers could persist for weeks, running into months. In these circumstances submitting themselves to mercury treatment was widely believed to provide a specific cure for their affliction. It is recorded in the CI registers that while about one quarter of all inpatients diagnosed with a venereal distemper reported they had been ill for only up to a month before they sought hospital treatment, three quarters waited rather longer, commonly reporting times of anything from two months up to a year, while a small minority (four) claimed to have been ill for well over a year before finally seeking treatment.Footnote 29

Thus, when using these institutional treatment records from the Chester Infirmary to form estimates of rates of treatment for genuine syphilis among all those initially diagnosed with ‘venereal distemper’, we need to be able to exclude the cases that probably do not correspond to syphilis. Devising a means to distinguish between patients suffering from syphilis and other venereal conditions not so distinguished at the time – notably gonorrhoea and chlamydia – is vital to the success of this exercise. Two rules have been adopted to achieve this. The first has been to discount all those with diagnosed venereal conditions who were not treated as inpatients;Footnote 30 the second, to discount all those who did not remain as inpatients in the hospital for at least 35 days, the normal minimal duration prescribed for the mercury cure (many hospitals at this time, including Chester's discharged patients on a once-weekly pattern). It is therefore being claimed that those remaining under treatment for a minimum of 35 days were believed by themselves and their doctors to have been suffering from the pox and this means they would be most likely to have been suffering from the condition we today define as syphilis. Among these patients by far the most typical pattern of treatment was discharge at either 35 or 42 days, with a minority staying longer, sometimes considerably longer.Footnote 31

Application of these criteria to the Chester hospital admissions register data results in the exclusion of a further 23 ‘venereal’ cases who were treated only as outpatients, plus 14 inpatients who were discharged in less than 35 days after admission, along with four others with deficient discharge date information, where it must be presumed that they did not remain in the hospital for very long.

Thus, of the original 174 useable cases a total of 106 have been excluded (65 + 23 +14 + 4), leaving 68. On further inspection of the names and ages of these remaining patients (which revealed incidentally that at least 8 individuals were probably married couples), one individual was identified as having been admitted twice.Footnote 32 There was therefore a total of 67 Chester residents of all ages treated for a ‘venereal distemper’ at the Infirmary for at least 35 days, indicating that they were being treated for the pox, with the probability of having contracted syphilis. Of these 67 patients, 9 were ages 35 or above, leaving 58 (86.56 per cent) under 35 years of age and therefore of relevance to form a comparable statistic of prevalence to those displayed above in Table 1. Thus, during the three years (1773–1775), an average of 22.33 Chester residents of all ages were treated per annum for the pox and an average of 19.33 patients per annum, who were under 35. Table 2 shows the numbers of patients of each sex at each age group.

Table 2 Numbers of venereal patients treated for at least 35 days in Chester Infirmary 1773–1775, by age and sex

Source: Chester Infirmary, Journal of patients (Admissions Register), 1773–1775.

3. THE DENOMINATORS: THE CHESTER CENSUS OF 1774

Due to Dr John Haygarth's innovative compilation of a full census survey of the entire population of Chester in 1774, there is available information on the numbers of each sex resident in the city.Footnote 33 The total city population he enumerated was 14,713, which will be accepted here as a substantially correct figure with which to develop the following analysis of age-specific denominators.Footnote 34

It should therefore be possible to use this exactly contemporaneous demographic information to provide an informed set of estimates of the probable numbers of men and women alive at each quinquennial age grouping between ages 15 and 34 in Chester in 1774. Once this has been achieved the numerators of the average number per annum of each sex being treated for syphilis in each five-year age group at ages 15–34 can be expressed as a rate relative to the appropriate denominator of the numbers of each sex alive in the city at those precise ages. This, in turn, will allow us to produce the most demographically rigorous overall pair of estimates for each sex of the population of Chester c. 1774, showing what proportion by age 35 had been treated for the pox at the Infirmary.

Before we can proceed to present the quinquennial rates of infection, we therefore have to provide the relevant denominators by estimating the most likely quinquennial age and sex structure of the population of Chester aged 15–34 in 1774. This is a necessarily protracted estimation process because Haygarth did not publish his census figures in five-year or ten-year age bands, the form that has since become conventional for demographic analysis, and so we need to construct the most plausible proportion alive at each of these ages with the assistance of life table modelling.

Haygarth published the total of each sex and also the totals under age 15 and over age 70 (but these figures were for both sexes combined). Very fortunately, he also published extremely detailed information from the registers of Chester's parishes for each of the three consecutive years (1772–1774), giving the numbers of christenings and baptisms in each year, numbers of marriages, and numbers of burials, with detailed distinction of ages at death (broken down into each of the first three months and subsequently each quarter during the first year of life). Consequently, this data offers the opportunity to make a precise empirical estimate, both of the size of the age group of each sex ages 0–1, and also of the prevailing infant mortality rate (annual burials under age 1 as a ratio of annual baptisms), which are extremely helpful for selecting an appropriate model life table to represent the age-specific mortality conditions prevailing in Chester in the early and mid-1770s.

Ansley Coale and Paul Demeny have published a well-known set of four ‘families’ of regional model life tables (named North, West, East and South) for varying mortality regimes across the world (in terms of the differing characteristic age-incidence of death met under diverse kinds of epidemiological regime).Footnote 35 For each of the four different regimes, the family of life tables offers a schedule of the successive age-specific rates of survival, from age 0 to age 80 and above, which can be expected to occur at a range of 24 different overall levels of mortality, ranging from an expectation of life at birth of only around 20 years (Level 1) up to around 75 years (Level 24). The Model North set of schedules have been used by Wrigley and his collaborators and are believed to offer the most satisfactory fit for the mortality regime of England during the second half of the eighteenth century into the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 36 To reach a final judgment about the most appropriate North model life table level to select for Chester c. 1774, involves a process of optimising consilience between a number of helpful items of independent, relevant evidence that can be brought to bear on the question of the prevailing mortality rates at this time in Chester. The process is additionally complicated, as we shall discuss below, by the fact that we must make appropriate allowance for the sex-differential pattern of net in-migration of young adults, which was primarily responsible for the quite marked overall sex-imbalance in the population enumerated by Haygarth.

To summarise in advance the procedures followed below, the helpful items of evidence available are as follows. Firstly, accepting that the population total of 14,713 in Haygarth's survey is approximately correct, the overall sex distribution is known: 6,697 males in comparison with 8,016 females. Secondly, Haygarth tabulated (unfortunately without distinction by sex) the proportion of the total population under age 15 and the proportion over 70. Thirdly, we have sufficient evidence to set the birth rate of each sex and the overall infant mortality rate, which is a major determinant for selection of the appropriate level of the North model life table.

John Haygarth's most detailed publications record, for the 3 years of 1772–1774, an annual average of 211.33 male births and 203.33 females.Footnote 37 This corresponds to a ratio of 104:100, which is extremely close to the expected ‘normal’ ratio and therefore can been taken as a sound empirical basis for the appropriate two numbers of each sex from which to base the 1774 life table, as shown below.Footnote 38 Secondly, the data for these three years includes information on all deaths under age 1, which total to 252. With 1,244 baptisms recorded, this equates to an average infant mortality rate of 202.6 per thousand births during the years 1772–1774. This indicates a level of infant mortality corresponding closely to Model North Level 7.Footnote 39

Next, we should consider whether an adjustment is required to these figures due to the well-known possibility that births and deaths of infants born to Catholics or non-conformists may have eluded Haygarth.Footnote 40 It is recorded that there were 130 Catholics living in Chester during this period, representing 0.88 per cent of the population.Footnote 41 There were also probably a little over 400 non-conformists in Chester, representing a further 2.75 per cent.Footnote 42 Haygarth does not explicitly discuss this issue, so there is insufficient information to know for certain whether and to what extent any of these groups were omitted from Haygarth's analysis. They would undoubtedly have all been counted in his survey of the resident population, the 14,713 inhabitants of the city. However, since he does not discuss the issue of their appearance in the registers at all, it seems most probable that he may have omitted to count non-Anglican baptisms and burials, if the parents did not attend the Anglican parish churches. As the Victoria county history (VCH) makes clear, most nonconformist congregations and also the Catholics did have their own separate places of worship at this time.Footnote 43 This would imply that the birth rate for the city should be inflated by approximately 3.63 per cent for each sex. However there is no reason to suspect that the rate at which this small number of non-Anglicans experienced mortality was substantially different from the average of the rest of the Chester population and so no further adjustment would be necessary to the life table in the ensuing exercise reported below to allow for these missing non-conformists, beyond the appropriate inflation of the city's number of births, as is undertaken below.

A further major issue that has to be addressed is that these model life tables are based on stable population theory, which means that they exclude, by design, the possible effects of migration. Yet we know that throughout the early modern period and on into the nineteenth century, migration was a widespread, strongly age-specific life-event, particularly among young adults aged 15–29.Footnote 44 A county capital, cathedral and major market town such as Chester tended to attract a substantial net inflow of young adult immigrants to its diverse service-sector sources of employment in the homes, artisanal workplaces and shops serving the unusual concentration of middle-class patrons and employers found in such administrative centres. There tended to be a great preponderance of young adult females in this migratory inflow.Footnote 45 The main direct corroboration that we have for this specifically in relation to Chester in the 1770s is the gross sex imbalance enumerated in the population in Haygarth's census, which found that 54.5 per cent of the population was female and only 45.5 per cent male. However, Haygarth's tabulation of his census data unfortunately does not gives us any precise information on how the excess females were distributed in the population with respect to age.

Given our keen interest in this whole exercise in trying to produce figures that are as accurate as possible for the denominator populations of each sex in the five-year age groups from age 15–34, and given the likely susceptibility of this age range to sex-specific migration effects, it would be helpful if we could refine the model life table's prediction of the numbers in these age ranges by reference to independent evidence of the likely pattern of young adult immigration – and perhaps emigration – to and from Chester. There is one category of primary source that can provide us with at least some guidance here in relation to Chester's demography. This is the decennial national census, which began in 1801. However, the first censuses that provide full details on numbers of each sex alive at different ages in the city of Chester (or indeed for any city in the country) are those of 1821 and 1841.Footnote 46 Unfortunately it is generally considered unwise to place too great a store by the age information collected at the 1821 census.Footnote 47

Although the 1841 census was conducted 67 years after that of 1774, the broad similarity of Chester's highly gendered employment patterns at the two dates is confirmed by the fact that while Haygarth's census in 1774 found an overall ratio of 835 males to 1,000 females, the 1841 census showed a similar, only slightly less imbalanced ratio of 866 males to 1,000 females. In addition, Table 3 also shows that Chester in 1841 was not markedly different in its proportions of the population below age 15 or above age 70.Footnote 48

Table 3 Chester's comparative age and sex ratios, 1774 and 1841 (males per 1,000 females)

Source for 1841: http://www.histpop.org

The evidence of the 1841 census offers the following age schedule of excess female sex ratios shown in Table 4. The second row in Table 4, ‘N. L8’, gives the ratios that would be predicted solely from the forces of mortality under the Model North Level 8 mortality regime, which is probably the best general fit for Chester c. 1841.Footnote 49

Table 4 Age-specific sex ratios in Chester 1841 (males per 1,000 females) and in Coale and Demeny's Model North Level 8

Source for 1841: http://www.histpop.org

Table 4 shows that the female imbalances in the Chester population in 1841 up to age 15 were not substantially different from that which would be predicted by normal, sex-differential mortality effects (which tend to favour female survival) under Model North Level 8. However, at ages 15–19 there is evidence of a much greater imbalance having been introduced into the 1841 age structure than can be accounted for by mortality effects alone. The presumption must be that this is due to sex-differential net in-migration. There is something like 120 extra females per 1,000 males in this age group and an additional 85 per thousand are present at ages 20–4, contributing to about 200 extra females per thousand males at ages 20–4. However, at ages 25–9, there is a substantial diminution in the imbalance with only about 50 extra females per thousand males at this point and only 40 at age 30–4.Footnote 50 The 1841 census raw figures confirm that the principal reason for the rapid fall in the sex ratio at ages 15–24 and also for the rebalancing of it at ages 25–34, is due primarily to patterns of net female migration, not net male movement at these ages.Footnote 51 There is no comparable contemporary evidence available for the 1770s to confirm definitively to what extent the age and sex-specific pattern of migration that can be established for Chester in 1841 was essentially similar to that which prevailed in the 1770s. It is clear from the overall sex imbalances at the two dates, however, that unless there had been a very considerable degree of net young adult male out-migration occurring in the 1770s which was no longer happening in the 1830s, it is highly probable that there was, indeed, a similar pattern of net young adult female in-migration into Chester in the 1770s, as was still the case in the decade prior to the 1841 census.

Continuity between the 1770s and the 1830s in the gendered labour market and associated sex-differential migratory patterns seems by far the most plausible conclusion to draw from other contextual evidence. The overall pattern of the city's characteristic economic and social structure did not change fundamentally – in the way that so many other urban places did – during the period from the 1760s until the 1830s. As the VCH observes, Chester in 1831 was still characterised by ’an absence of factories’ so that, ‘The poor formed a smaller proportion than in manufacturing or commercial towns and were mainly employed in domestic service’ by ‘an unusually large resident gentry’, attracted by Chester's long-established fashionable social scene.Footnote 52 The 1831 census, the first to attempt to record occupations in some form, found that in Chester there were 1,260 female servants employed (as opposed to 172 male servants) and still only 60 persons in manufacturing, as against 2,641 in retail trade or handicrafts.Footnote 53 The railway did not arrive in Chester until the 1840s, after which there was, indeed, significant expansion of industry (as also finally happened at the same time and for the same reason in York, too).Footnote 54 Chester therefore remained in the early nineteenth century decades a town that continued to grow only moderately, as it had done during the second half of the eighteenth century, without the stimulus of new manufacturing industry in the city. Consequently its rate of growth was slower than many other cities in the region.Footnote 55 Given this unusual degree of continuity in its economic character between the 1770s until the 1840s, we can be more confident that the demographic record left at the 1841 census is not an unreasonable guide to the demography of migration to the city in the 1770s, at least with respect to the issue which we are addressing here, which is the exact extent to which the city's overall sex imbalance was due to patterns of gendered net in-migration during the key age range of 15–34, which was related to the continuity of demand in the female labour market for servants and retail workers.

Thus, in the final version of the life table model developed here, net migration patterns in Chester c. 1774 have been envisaged as consisting of 150 females in-migrating and 41 males out-migrating between ages 15–24; followed by a net outflow of females, only, at ages 25–9, equivalent to a little over half the total number who in-migrated at ages 15–24. This produces a similar pattern of changing age-specific sex ratios across the ages 15–34, to that evident for Chester in the 1841 census as shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Ages-specific sex ratios at ages 15–34 (males per 1,000 females) in Chester 1841 (census) and in migration-adapted Model North Level 7 life-table (see Tables 6A and 6B) for Chester c. 1774

Source for 1841: http://www.histpop.org

The net outcome of these necessarily detailed considerations results in the migration-adjusted Model North Level 7 life table for Chester, which is presented in Tables 6A and 6B. This gives a best estimate of the detailed age structure of the population of Chester in 1774 when Haygarth took his census. The basic pattern of the age structure has been created by applying the survival probabilities of Model North Level 7 to a population conforming to the primary constraints that the number of males should sum to 6,697 and the number of females to 8,016. The numbers of each sex born at age 0 has been set as the annual average of the numbers of each sex baptised 1772–1774, as recorded by Haygarth, subject to a 3.63 per cent inflation of each number to allow for the likelihood that christenings of Catholics and non-conformists born in the city were not included in his count from the Anglican parish registers. The sex ratio of these births was 104:100 males:females. In addition to this, as shown, an estimate of a plausible degree of net in-migration of females at ages 15–19 and 20–4 has been included, along also with a degree of net out-migration of a smaller number of females at ages 25–9. These correspond to similar absolute rates of migration per 1,000 to those found at the census of 1841 and they conform to a similar age-related pattern. A much more modest degree of net male out-migration at ages 15–24 has also been included in the model.Footnote 56 The resulting modelled age structure produces estimates of the proportion of the population under age 15 of 28.9 per cent, which is close to Haygarth's calculations of 30.5 per cent and a figure for the proportion over age 70 of 3.5 per cent, which is similar to Haygarth's figure of 4.3 per cent. The models produce estimates of the total populations of each sex, which have been set to match exactly Haygarth's observed figures. Experiments with Model North Levels 6 and 8 showed that the use of Level 8 produced a sufficiently higher survival rate of each sex that it would have been necessary to hypothesise very little in-migration of young female adults and relatively large-scale out-migration of young male adults to avoid a large over-count of both sexes relative to the totals of each sex enumerated by Haygarth. While, to the contrary, application of Level 6 produced such low survival rates among males in particular as to require very high rates of male in-migration to reach the total of males enumerated. Neither of these implications seems at all plausible and therefore Model North Level 7, augmented with appropriate migration modifications, would appear to be the optimal choice to model Chester's life table in 1774 to achieve consilience with all the known independent sources of evidence.

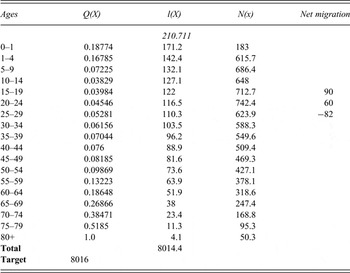

Table 6a Life table of females alive at different ages in Chester c. 1774, Model North Level 7 with a birth rate of 210.711; adjusted for estimated net migration flows at ages 15–29

Notes for Tables 6a and 6b : Q(X) = probability of dying during the age range (derived from Model North Level 7); l(X) = average annual number alive in the age-group; N(x) = total numbers enumerated alive in that age group at a census exercise; Net migration = net numbers entering or leaving Chester in that age-range.

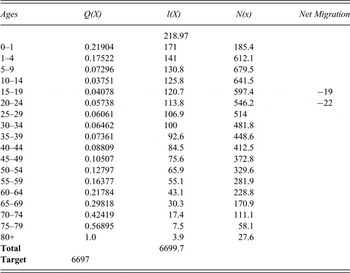

Table 6b Life table of males alive at different ages in Chester c. 1774, Model North Level 7 with a birth rate of 218.970; adjusted for estimated net migration flows at ages 15–24

4. THE RATES OF TREATMENT FOR THE POX AT THE CHESTER INFIRMARY

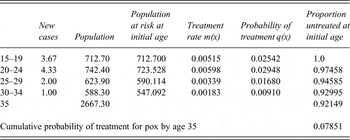

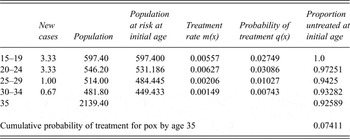

Tables 7A and 7B bring together the numerators and the denominators constructed in the previous sections of the article to offer calculations for each sex of the proportion of the Chester population in each five-year age group who had been treated for the pox by age 35 during the period 1773–1775. As also shown, the five-year rates of treatment can then be cumulatively summed to produce a single percentage figure for each sex, showing the proportion of the Chester resident population c. 1774 who, by age 35, had been treated for an infection with pox at the Chester Infirmary. This is a figure that is constructed so as to be statistically comparable to the estimates produced elsewhere for the population of England and Wales in 1911–1912, which, because they were based on Wassermann tests, gave the proportion of men who had ever been infected with syphilis at any point throughout their lives up to their mid-thirties.Footnote 57

Table 7a Female cumulative chance of treatment for pox at Chester Infirmary 1773–1775

Source: See Table 2.

Table 7b Male cumulative chance of treatment for pox at Chester Infirmary 1773–1775

Source: See Table 2.

Tables 7A and 7B show that among the Chester population c. 1774, 7.851 per cent of females and 7.411 per cent of males had been treated for the pox in Chester Infirmary by the time they reached age 35.Footnote 58 Taking into account the sex ratio imbalance in the town at ages 15–34, these calculations indicate an overall general rate of infection by age 35 for both sexes combined of 7.655 per cent.Footnote 59

However, the production of this overall estimate derived from these age-specific rates for each sex probably represents an underestimate of the cumulative incidence of pox by age 35 for the entire population of Chester. This is because two sections of the Chester population may be missing from the evidence reviewed so far; and so further considerations are required and possible further adjustments needed. One group who may have been omitted are the indigent poor, whose first port of call in the 1770s would have been the Poor Law House of Industry, which could have contained some form of infirmary provision.Footnote 60 The second missing section is the genteel class. This refers not just to the economic elite – those few dozen individuals who would, for instance, have figured among the subscribers to the hospital – but a somewhat wider section of society. This was Chester's substantial middle class, those who could afford the fees to engage privately the city's physicians and who would likely have done so to avoid the unwanted publicity about their condition that could follow from applying for residence in the city's hospital for the protracted treatment required.

The first possibility is that paupers who had contracted the serious condition identified by contemporaries as the pox were retained and treated within Chester's House of Industry rather than sent to the nearby Chester Infirmary (the two institutions were within a quarter mile of each other on the west side of the city). In fact, this seems unlikely from the available evidence. The conclusion of the research team of the VCH’s recent volume on the city of Chester during this period is that, ‘Patients from the workhouse on the Roodee were treated by the [Chester] infirmary's physicians and surgeons from 1759, and from 1784 the guardians of the poor were regular subscribers to the infirmary.’Footnote 61 In relation specifically to venereal diseases, this conclusion is supported by the positive evidence from the three years of Chester Infirmary registers analysed for this article, 1773–1775, which do show venereal patients admitted to the Chester Infirmary from the House of Industry.Footnote 62 This conclusion is also supported indirectly by the approximate equality of numbers and proportion of the two sexes treated for pox at the Chester Infirmary. This contrasts with London, where Siena has found that the voluntary subscription hospitals in the eighteenth century tended to cater disproportionately for males, while female patients appeared to constitute a balancing preponderance of those treated in workhouse infirmaries.Footnote 63 The fact that this sex-specific pattern seems to be absent from the Chester Infirmary records confirms that the House of Industry was not providing alternative treatment facilities.

5. CHESTER'S SOCIAL ELITE

The section of Chester's population that was unlikely to be represented among those being treated in the subscription hospital was the social elite and the genteel classes, those intent on avoiding public exposure if constrained to seek treatment for a shameful venereal condition. There is considerable speculation and rather little systematic evidence available on exactly how this section of society obtained treatment for venereal conditions. The absence of much surviving evidence reflects the fact that an integral part of what the genteel class was paying for in consulting a medical professional was confidentiality.Footnote 64 Among those who could afford it, to seek qualified medical treatment made perfect sense therapeutically because, as noted above, the pox was one of the very few conditions on which there was widespread professional and lay consensus in the late eighteenth century that an effective cure was available through a course of mercury salivation. While the significant cost of private treatment was not necessarily a deterrent to this class, the protracted and gruelling nature of the cure was; and also the fact that the intense and debilitating treatment tended to remove patients from social circulation and from their business activities for several weeks. Hence, the perennial appeal of quack and patent remedies for all embarrassing venereal conditions in this era, even though it was believed that professional medicine could cure it.

As Roy Porter has put it, ‘the claim to cure the pox without recourse to mercury was cardinal to all quack therapies’ since ‘mercury treatment was inevitably conspicuous’; consequently, ‘Quacks claimed … a form of invisible mending … “secret treatment” … not even one's bedfellow need know’, since ‘[quack] nostrums could be taken as people went about their business’.Footnote 65 Such nostrums tended to be quite expensive in the 1770s, equivalent to half or more than a labourer's weekly wages.Footnote 66 However these prices were affordable for the genteel classes. It is perfectly plausible therefore that there was both a buoyant market for clandestine and quack medicines (which may have appeared to work at times – especially in non-syphilitic cases) and also for orthodox medical treatments from the same relatively privileged section of society, indeed from the same individuals at different stages in their illness. If it was, indeed, syphilis that they had contracted – the pox and not merely the clap – they would eventually progress from hopeful self-medication to the necessity of the mercury cure.

It is most unfortunate that the detailed case notes of Dr John Haygarth, meticulously kept for over 10,000 consultations during his three decades of practice in Chester, appear to have been lost to posterity; and it is unlikely that any comparable detailed source will appear for the 1770s that could provide a substitute for direct information on the extent to which this class in Chester sought treatment for syphilis.Footnote 67 Consequently the only viable approach would appear to be an estimation procedure. This can be accomplished by first assessing what proportion of the Chester population was composed by the genteel class; then attributing to that class a similar rate of venereal infection, on average, to that which we have found for the generality of the Chester population;Footnote 68 finally, inflating the overall Chester rates to allow for these imputed missing genteel cases.

There is no comprehensive census-style information on the social structure of Chester before the 1851 census. A detailed street map of 1745, drawn by the surveyor Alexander de Lavaux, did locate the households of the town's most notable property-owners but that cartographer in fact listed only 20 such individuals (all styled ‘esquire’), which may give some indication of the relatively small numbers of the oligarchic social elite at this time in Chester.Footnote 69 For a more encompassing estimate of the size of the genteel class in Chester in the 1770s there is one particularly helpful near-contemporary source. For most of the eighteenth century the parliamentary borough of Chester and its two MPs were in the hands of the powerful Grosvenor family of Eaton Hall (situated three miles from Chester). However, in 1784 the parliamentary election was genuinely contested by an independent, John Crewe.Footnote 70 Since Chester borough's two MPs were returned by a ‘resident freeman’ franchise, this contest generated a record of the names, addresses, occupations and voting preferences of all males voting.Footnote 71 As it was an unusually sharply contested election this resulted in a large turnout and a list of as many as 1,118 individual voters. Such a list, though certainly not containing a complete record of all the town's voters, enables us to form a helpful, empirically-based estimate of the number of adult males in Chester's genteel elite.

As Rosemary Sweet has pointed out, this election was the result of simmering resentment since 1771 on the part of an independent section of the commercial and shop-keeping interests in Chester due to the Grosvenor family's failure to support a local canal project.Footnote 72 With a serious threat to their control over the two parliamentary seats for this first time in living memory, the Grosvenors spent exceptionally heavily on the 1784 election to mobilise full support from the dense network of friends, associates and the diverse dependents on their widespread local patronage, built up over generations.Footnote 73 Such support for their two candidates could later be inspected at leisure by the Grosvenors when considering whom to continue to favour, given the public nature of the list recording the votes cast.Footnote 74 Thus, most of Chester's resident genteel elite and most of the voting middle classes, too, can confidently be expected to be enumerated from this list, wishing to demonstrate their loyal support for the Grosvenors in their time of need – or taking their opportunity to express their displeasure.Footnote 75 The genteel can be identified in the first instance through certain personal occupational designations: all those with an occupation simply listed as ‘Gentleman’ or ‘Esquire’, including three urban-dwelling ‘Farmers’ (though several ‘Yeoman’ were not counted here as genteel). Secondly, all those listed with a senior civic function such as Mayor or Alderman (but not the junior functions of, for instance, ‘Sheriff's Officer’ or ‘Macebearer’). To these can be added also those with a professional occupation listed, such as attorney or ‘M.D.’ (including here ‘Druggists’ and ‘Schoolmasters’).Footnote 76 Fourthly, there are the more successful among a diverse range of commercial occupations related to dealing, shopkeeping and master-craftsmen or large employers. A detailed study by Mitchell provides invaluable guidance here. From his study of Chester's retailers at this time, Mitchell concludes that the more prosperous and substantial traders were to be found only among the grocers, drapers, mercers, wine merchants, hatters and goldsmiths, while most other trades appearing on the list of voters, such as bakers, tailors, cordwainers, shoemakers and household goods dealers, comprised a more humble category, alongside also the many master craftsmen numbered among the city's freemen.Footnote 77

This procedure produced a total of 211 individuals classified in this way as genteel from the 1,118 names on the voting list.Footnote 78 This is a figure that coincides quite closely with an independent near-contemporary source from a decade later, a 1792 directory listing 222 families in Chester headed by a ‘gentleman’, which Frank O'Gorman has also cited as a useful indicator.Footnote 79 These 211 ‘gentlemanly’ voters represented approximately 5.3 per cent of all men in Chester aged 21 and over.Footnote 80 To put this into context, if we assume that among these genteel voters very few under the age of 25 were married heads of household but most of those over age 25 were married, the life table indicates that this would add up to about 183 married individuals from the total of 211. That would have represented between one in four and one in five of all heads of family households living in the six more affluent and salubrious inner parishes contained entirely within the walls of the city. In other words, although the genteel elite comprised only just over 5 per cent of all male inhabitants of the city in 1774, they comprised about 20–5 per cent of all family householders in the six central parishes.Footnote 81

The analysis of this primary source would therefore suggest that the best estimate for the number of adults in Chester's populace composing a genteel elite, who would have been in a position to have sought and paid for discreet, private treatment when infected with a venereal disease that they thought was the pox, was approximately 5.3 per cent of the city's population. This exercise therefore indicates that the overall figure of pox infection for Chester of 7.655 per cent derived from institutional treatment records, should be further increased by a factor of 5.3 per cent to account for the missing genteel section of society likely to have paid for private treatment, producing a final estimate of almost exactly 8 per cent (8.0607 per cent).

6. THE COMPARATIVE INCIDENCE OF VENEREAL DISEASE IN CHESTER'S RURAL HINTERLAND

The admissions registers of the CI may also be used to provide an indication of the relative extent of the venereal diseases in the more rural population of Chester's economic and social hinterland, since the CI was founded with a truly regional vision to serve all those communities which looked to Chester as their nearest city. Hence, the subscription strategy at its launch focused on drawing financial support from the clergymen and leading inhabitants of the county of Cheshire's main towns and also those of the two adjacent Welsh counties immediately to the east, Flintshire and Denbighshire. There was a strong sense in which the CI was funded and perceived as the major medical resource for the entire county and also the two under-provided neighbouring Welsh counties.Footnote 82 It is recorded in the Minutes of the Board and General Meeting that at the initial meeting of the subscribers of 22 April 1755 there was agreement to enter into correspondence immediately to receive subscriptions and benefactions from both the resident clergy and also from specified gentlemen in all the principal towns of the county: Nantwich (6 gentlemen specified); Middlewich (2); Northwich (5); Knutsford (2); Stockport (3); Altrincham (2); Macclesfield (4); Congleton (3); Frodsham (2); Malpas (3); and Sandbach (3).Footnote 83 Although no attempt was recorded to make contact with clergy or gentlemen in Liverpool, Manchester, Warrington or anywhere in Lancashire north of the Mersey–Irwell border, there was a specific effort made in the direction of the two nearby Welsh counties. It is recorded that circular letters were to be written ‘to the several Clergymen of this and neighbouring Counties in Wales, with copies of the subscription papers desiring them to solicit benefactions and subscriptions.’Footnote 84 Consequently, it is recorded in 1778/9 that while 70 per cent of recorded subscribers were Chester residents, 18 per cent were from the rest of the county and 12 per cent from north Wales.Footnote 85

In view of this, it not so surprising to find that as many as 37 per cent (64/173) of CI admissions treated for venereal infection in the years 1773–1775 were recorded as resident outside the city of Chester. Of these 64 patients residing outside Chester city, 22 were treated for 35 days or more (the criterion adopted here for counting the patient as most likely suffering from the pox).

Of course, prima facie, it would seem most probable that those suffering from venereal diseases but not residing in Chester itself would be much less likely on average to appear in the register of the CI than an inhabitant of the city of Chester. Though, interestingly, it is relevant to note that the general assumption that might be held that rural dwellers were likely to be less amenable than urbanites to uptake of medical treatments and innovations in this period is flatly contradicted by the experience many contemporaries reported, including Haygarth himself when specifically comparing Chester with Cheshire, of rural consent for smallpox inoculation as against urban indifference or resistance to it.Footnote 86

Those living outside Chester could in theory have requested to be treated privately by one of the medical men in several of the region's market towns. However, that would only be possible if these practitioners provided this service, which required specialist equipment and training and the capacity to care for a patient during a period of several weeks of residential care. Most of the licensed practitioners listed in Samuel Simmons's Medical Register in the market towns of Cheshire, Denbighshire and Flintshire were modest, usually single-handed surgeons and/or apothecaries, who lacked the university education and resources of a physician. Therefore, they would have been less likely to have the training and facilities to offer this form of more expensive and intensive care to their clients.Footnote 87

How best, then, to use this geographic distribution of registered cases to form an estimate of the relative prevalence of the pox in the rural environs of Chester, representing a less urbanised populace? It is clear that, given the presence of medical practitioners, albeit very few of them physicians, in the other market towns of Cheshire, that they may have treated a number of ‘poxed’ venereal patients who never appeared in the CI register. However, we do have positive evidence that a number of those with this serious condition were not treated locally and were recommended to the CI from as far afield as Stockport and Congleton, each of which had several resident medical practitioners, though we cannot know what proportion of those with such symptoms in these towns they constituted.Footnote 88 However, in relation to Chester's more immediate rural hinterland, the part of the Cheshire population residing within a ten-mile radius of the city's centre, these considerations of alternate sources of medical treatment probably do not apply. There were no other market towns within this radius in Cheshire or north-east Wales, though Neston to the north in the Wirrall peninsula and Frodsham to the north-east on the south bank of the Mersey, were each at ten miles distant and each had one Surgeon or Apothecary resident in 1783. The next nearest market town was Malpas, 13 miles to the south. There is in fact a relatively even spread of rural patients appearing in the CI registers listing their residence in parishes up to ten miles from Chester (see analysis below), with rather fewer cases appearing from small rural settlements beyond that distance.Footnote 89 This suggests that such rural inhabitants may have been more likely to seek treatment in the other market towns of the county and of North Wales if they lived further than ten miles from Chester.

There were 15 patients in the CI register who were retained for treatment for a venereal distemper for at least 35 days and resided within ten miles of Chester's centre.Footnote 90 They exhibit a very similar sociodemographic make-up as the equivalent group of patients from within Chester city (see Table 2), in that 7 were females, 8 males, with the great majority (80 per cent) under age 35 and a preponderance of females in this age range (7:5), whereas overall there were slightly more males (7:8) because all 3 of the older patients above age 34 were male, a similar age and sex pattern to that of Chester residents.

If we treat these 15 inpatients as representing the numerator for the rate of pox infection among this population of Chester's immediate rural hinterland within a radius of ten miles over the three years 1773–1775, it is possible to estimate an approximate gross population denominator from which they were drawn. Tony Wrigley has provided estimates of the population size of Cheshire's seven ancient geographical units known as ‘Hundreds’ for the period 1761–1801, drawing from previously unutilised historic information provided in the 1801 census volumes.Footnote 91

Drawing a ten-mile radius from the centre of Chester takes in the northernmost two thirds of the Broxton Hundred, within which Chester itself was located. It also takes in the southernmost one third of Wirrall Hundred and an eastern section of about one third of Eddisbury Hundred (the part to the west, south and north of Delamere Forest). In addition, this ten-mile radius includes the north-eastern quarter of Flintshire, comprising the parishes of Hawarden, Dodleston, Northop, Hope and Gresford; and also the parish of Holt in the north-eastern corner of Denbighshire.Footnote 92 The boundary towns on the circumference of this circle are: Neston to the north-west, Frodsham to the north-east, Tarporley to the south-east, Gresford (just north of Wrexham) to the south-west and Mold to the west (though, unlike the other four boundary towns Mold itself is excluded, as it falls half a mile outside the ten-mile circumference). This is a predominantly rural and fairly evenly populated circle of territory of approximately 290 square miles.Footnote 93 This mainly agricultural land contained no settlements above 1,500 inhabitants in 1801 at the first census.Footnote 94

To estimate the most probable size of the rural population residing within this circle of territory c. 1774, we should first take appropriately interpolated figures from Wrigley's estimates for the total populations of the three Hundreds of Broxton, Eddisbury and Wirrall (note that neither Birkenhead nor Ellesmere port were more than small settlements at this time) and deflate those figures by the proportions of the territory of each Hundred lying within the area of the circle. Secondly, we should add to this the recorded census population totals for the single Denbighshire and the five Flintshire parishes in 1801 and then apply a slight adjustment for these six parishes to reflect their likely population sizes 25 years earlier.Footnote 95 We will then have an estimate of the rural population in this circle of territory to take as a gross denominator to set against the numerator of infected individuals treated for the pox at CI, 1773–1775, and to compare with the comparable rates of treatment for the population of Chester itself. This estimation procedure indicates that the rural-dwelling population at risk in the 290 square miles comprising a ten-mile radius from the centre of Chester c. 1774 was approximately 33,087 persons, a little over twice (2.24 times) the total population contained within the city of Chester, as enumerated by John Haygarth, at 14,713 persons in 1774.Footnote 96

During 1773–1775 there were, therefore, a total of 15 inpatients of all ages treated for over 35 days in CI, who were resident in these rural settlements within a ten-mile radius of Chester city, a rate of 5.0 per annum. During the same period there were 67 such patients treated from Chester city's residents, a rate of 23.0 per annum, approximately four-and-a-half times greater (4.6 times) per head of population. As noted, the age and sex composition of the two sets of inpatients, from Chester city and from Chester's rural vicinity, was similar. This set of calculations from the evidence that is available would therefore indicate that the population resident in Chester was approximately 10.3 times (2.24 × 4.6) more likely to require treatment for the pox than the surrounding rural population. However, it must be borne in mind that, with its young adult female net in-migration pattern, a substantially higher proportion of Chester city's population was in the prime at-risk age groups. It seems most likely that Chester could have had about 16 per cent more individuals in this age range than its rural hinterland.Footnote 97

The ratio of 10.3 should therefore be reduced by a factor of about 16 per cent to reflect the proportionately larger at risk population in Chester city. This indicates, as a final estimate, that the population resident in Chester was approximately 8.65 times more likely to contract a venereal disease requiring inpatient treatment for at least five weeks in Chester's Infirmary than was the case for the population inhabiting the immediately surrounding 290 square miles of less densely settled countryside.

Note that because this comparative exercise is evaluating relative relationships, for its conclusions to have validity it is not necessary to presume that all those suffering with pox symptoms were treated at the CI; it is only necessary to assume that those living within ten miles of Chester did not fail to appear in the register to any significantly greater extent than those residing in the city. It is fortunate that an empirical test of this assumption can be offered with the data available since it is possible to examine whether there are any signs that distance from Chester affected the rate at which infected rural patients appeared on the CI register. A total of 6 patients came from the 108 square miles that lay within a six-mile radius, a total of 9 from the 197 m2 lying within a eight-mile radius and 15 from the 290 m2 that fell within the full circle of ten miles from the centre. This equates to 1 patient per 18.0 m2, 1 per 21.9 m2, and 1 per 19.3 m2, respectively.Footnote 98 This indicates no systematic decay effect with distance up to ten miles, which is conducive towards accepting the validity of the assumption. This test therefore confirms that the ratio of approximately 8.65:1 may be a relatively faithful measure of the difference in relative rates of infection requiring treatment, between the urban Chester populace and the rural population of the surrounding agricultural hinterland.

6. CONCLUSION

The foregoing has resulted in two empirically-based estimates of the population prevalence of venereal diseases in the 1770s.Footnote 99 One relates to Chester, a second-rank city of the period and county capital; and the other to an entirely rural population comprising the agricultural communities of the western part of the county of Cheshire and parts of the immediately bordering Welsh counties of Flintshire and Denbighshire within ten miles of Chester. The measure that has been adopted relates to individuals who were supposed by themselves and by medical attendants to have contracted ‘the pox’, a condition necessitating an inpatient treatment of at least 35 days duration in the Chester Infirmary. This is the diagnosed disease condition most likely to correspond to infection by the bacterial spirochaete, Treponema pallidum, which is today known to cause the STI known as syphilis.

It has been concluded that the best estimates that can be constructed from the evidence presented here indicate that in the mid-1770s in Chester city approximately 8 per cent of its residents had been infected with syphilis before the age of 35. The rate of infection in the surrounding rural communities was found to be about 8.65 times lower, indicating an infection rate by age 35 of a little under 1 per cent (0.93 per cent). The evidence for both Chester and its rural hinterland indicates relatively equal rates of infection for both sexes, with a slight preponderance among females under age 35, though, overall, males were more likely to contract the disease because of their greater preponderance at higher ages (though there are far less cases per head of population at these higher ages).

Contrasted with comparable rates calculated for males 140 years later, shown in Table 1, the inferred rates of cumulative infection by age 35 found in the city of Chester are similar, though a little lower, to those found in Britain's large, second-rank provincial cities just before the Great War – though of course those cities were incomparably much larger than Chester in 1774. By contrast, inferred rates of infection in rural west Cheshire and north-east Wales appear to have been extremely low, both by comparison with Chester in 1774 and by comparison with rural places in 1911–1912. However, such rural communities in 1911–1912, rather than representing the norm where the majority of the national population resided as in 1774, represented by 1911 only a small residual minority within the most highly urbanised society in the world. This absolutely low rural incidence in the 1770s is of course significant in assessing the general prevalence of the venereal diseases in the late eighteenth century, since such rural locations were still at this time the most typical place of residence for the majority of the British population.

Thus, the research reported here has shown that it is possible, given the good fortune of the survival of the right combination of records, to produce empirically-based robust estimates of the comparative incidence of syphilis. Note that there is no claim here that all who were judged to have the pox must definitely have had syphilis, nor that all inpatients treated for 35 days must have been suffering from syphilis, and only from syphilis; nor that none with syphilis were discharged in less than 35 days; nor that all who believed themselves to have the pox necessarily submitted themselves to treatment. This exercise has produced a probabilistic estimate, requiring judgments of plausibility drawing both on our understandings of contemporary beliefs and on the current state of knowledge about the STIs for its construction, and is subject to the limitations of the primary sources. It is only contended that such an estimate is more helpful than none at all; not that it offers precise and certain knowledge.

If other scholars concur with this, it may be hoped that in the future others might be able to identify primary sources permitting the construction of comparable measures for other dates and related to the populations of other locations – perhaps in other countries, too. This may eventually enable demographic and epidemiological historians to integrate an understanding of historic STIs into reconstructions of population history across the recent centuries of rapid transformation, urbanisation and expansion. These are undeniably important diseases in relation to mortality, fertility and migration, especially in urbanising populations. While syphilis causes miscarriage, stillbirth, perinatal and infant mortality (as well as adult mortality in its tertiary stages), gonorrhoea and chlamydia both cause secondary sterility in a proportion of those infected in both sexes. Furthermore, as discussed elsewhere, it has been shown that gonorrhoea typically afflicts about three to four times more of the population than syphilis, due its much greater degree of infectiousness (which is also true of chlamydia).Footnote 100

Nevertheless, the results reported here would suggest that the previously concealed history of the STIs is unlikely to alter substantially the rich range of insights produced in the two major early modern demographic history publications by Wrigley, Schofield, Oeppen and Davies, since the bulk of the evidence they presented related to rural parishes. However, rural England and Wales is not the whole story, of course, and as researchers now increasingly probe the early modern demographic history of urban parishes and populations, including London, the results reported here indicate that STIs probably were a much more significant epidemiological feature, and their influence needs to be carefully considered. If about 8 per of each sex had, by the age of 35, voluntarily undergone the arduous treatment required for a suspected case of the pox in a second-rank city such as Chester, what comparable proportion might have been afflicted with STIs in the many much larger provincial cities about to emerge early in the next century? And what might have been the prevalence of these diseases already in the 1770s in the Great Wen, the world's largest city half a century before William Cobbett coined this nickname in the 1820s? Kevin Siena has presented compelling evidence that many institutions were treating the pox there in the late eighteenth century.Footnote 101

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research for this article was completed as part of the Wellcome Strategic Award to Cambridge University, ‘Generation to Reproduction’ Award Number 088708. With thanks for their advice to: Kevin Siena, Rosemary Sweet, Romola Davenport, Samantha Williams, Jeremy Boulton, Tony Wrigley, Hilary Cooper, Ron Lee, Jim Oeppen and Ian Timaeus. The entries in the Chester Journal were transcribed by Sam Szreter. Thanks also to participants at seminars presenting earlier versions of this article in Cambridge, Oxford, London, Baltimore, New York, Berkeley, Canberra and Sydney and to the three anonymous referees of this journal for their improving comments.