No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

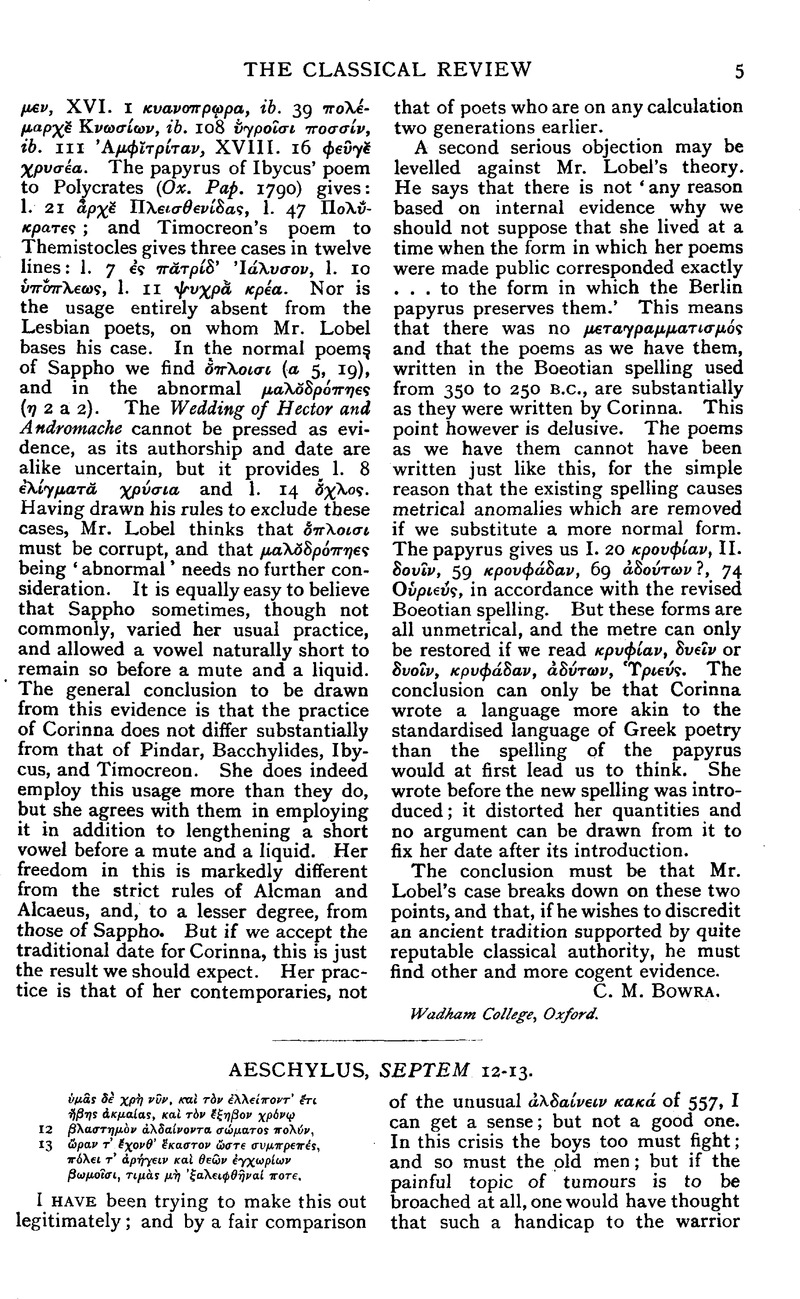

Aeschylus, Septem 12–13

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1931

References

1 The transference is direct; not springtime-time↣ generally↣prime of life, but spring of year↣ spring of life. Eur. Suppl. 447–9; cf. εφηβoι … εαρ τû δημoν, Demades Fr. 4 S. Cf. the famous simile of Pericles, Ar. Rket. 1.7,34 and III. 10,7. Hdt.VII. 162 may not be the misapplication it seems, and the concluding sentence of How and Wells's note is instructive in our connexion.

2 Because, while men in their prime are buĺkier than boys, there are such things as bulky (and still healthy) old men. But indeed, if physiology were to decide the question, the phrase should be most applicable to ol έλειπoντεΣηβηΣ since the period of greatest growth is (after prenatality) infancy. And these physiological facts are correctly stated by Plato, Laws VII. 788D ff. For our poets, however, it suffices that the period when a man has the maximum of healthy muscle to ‘feed’ shall be regarded as his prime of growth. In old age he may shrink or go puffy.