Introduction

Primary care physicians are in a privileged position to recognize sexuality as a core component of health, and to guide patients in attaining wellness in this aspect of their lives. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as the “state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity” (World Health Organization, 2006). Although sexual activity appears to decline with age, more so in women than in men, the number of individuals who continue to be sexually active remains significant (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). In 2007, data from the United States National Social Life, Health and Aging Project indicated that more than 50 per cent of the population 57–85 years of age and approximately 30 per cent of those 75–85 years of age continue to be sexually active (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). Data from other developed nations are lacking. As sexuality is a lifelong experience, a deeper understanding of sexual health should be a priority across all age groups.

Investigating sexual health concerns can provide physicians with a lens into patients’ perceived well-being as well as inviting discussion that could improve overall health and quality of life. The 2009 American Association of Retired Persons survey identified that individuals at mid to later stages of life who reported “good health” were more likely to have a sexual partner and be sexually active (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Anderson, Champagain, Montenegro, Smoot and Takalkar2010; Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). Sexual satisfaction was also associated with increased self-ratings of overall health (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Anderson, Champagain, Montenegro, Smoot and Takalkar2010; Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). Furthermore, sexual activity was less prevalent in those who reported their general health to be fair or poor (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). As such, proactively addressing patients’ sexual health concerns may reveal underlying ailments preventing them from being sexually active and serve to improve their overall sense of wellness. However, communication about sexual health between patients and their health care providers is lacking in the primary care setting. Only 38 per cent of men and 22 per cent of women over the age of 50 reported having discussions concerning sex with their physician (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). Both patient and physician factors may be responsible for this lack of communication, including inadequate physician training, poor understanding of the sexual health needs of mature adults, and patients’ comfort level with their health care providers (Gott, Hinchliff, & Galena, Reference Gott, Hinchliff and Galena2004; Omole et al., Reference Omole, Fresh, Sow, Lin, Taiwo and Nichols2014; Ports, Barnack-Tavlaris, Syme, Perera, & Lafata, Reference Ports, Barnack-Tavlaris, Syme, Perera and Lafata2014).

Currently, only one large study from the United States, published in 2007, has addressed the changes in sexual health that occur with physical changes associated with aging (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). Canadian data examining the sexual behaviours of the aging population and the role of primary care providers in supporting health in this domain are lacking. The purpose of this cross-sectional study is to better characterize the sexual health needs of patients over the age of 50, with the a priori goal of comparing differences between female and male genders. Highlighting the importance of sexuality to patients as they age as well as identifying areas of improvement in sexual health care will help primary care providers better address the needs of their patients.

Methods

Study Setting

A survey was administered to patients belonging to the St. Michael’s Hospital Academic Family Health Team (SMHAFHT) in Toronto, Ontario. The SMHAFHT provides comprehensive primary care to approximately 48,000 patients at six clinical sites located within the downtown core. The general patient population consists of individuals from a variety of age groups, ethnicities, and socio-economic backgrounds, a large proportion of whom are considered to be socially marginalized.

Study Design

A cross-sectional survey was administered to eligible participants as they checked in for an appointment during the study period (June 12, 2015 to October 7, 2015). Clerical staff identified all patients over the age of 50 who had previously scheduled appointments with their physician during the study inclusion period. Once identified by the clerical staff, members of the research team approached the potential participant to review the details of the study and ensure that the participant met the inclusion criteria (age > 50, English-speaking, men or non-pregnant women). Consent was implied by completion of the study survey. Participants completed an anonymous, paper-based survey that included basic demographic information (age; gender, including transgendered male to female or female to male; marital status), general health history, sexual health history and active sexual health concerns (Appendix 1). Respondents were also asked if they discussed their concerns with their primary care provider and were asked to rate the importance of sexual activity using a five point Likert scale. Information on active sexual health issues as well as discussions with their primary care physician regarding these concerns were included in the survey.

As this was a descriptive study to describe the sexual health needs of older adults, we did not have any hypotheses driving our exploratory analysis and, as such, did not conduct a sample size estimate.

The study was approved by the St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Likert scale data were grouped when appropriate; for example, responses of 1 or 2 were grouped as a response of “Not Important” and responses of 3 or higher were considered “Important”. Analyses were stratified by gender where applicable. A p value of 0.05 or less was considered to be statistically significant. Missing values were excluded from the statistical analysis. Cell sizes of five or less were suppressed. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and GraphPad Prism Version 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA).

Results

Eight hundred and eleven patients were approached, and 511 agreed to complete the survey (response rate of 63%). The mean age of females in the study was 64.6 years (standard deviation [SD] 10.2 years), and the mean age of males was 63.1 years (SD 8.5 years). A total of 243 female (48%) and 263 male (52%) participants completed the survey. Twelve females (6%) and 52 males (23%) identified themselves as having a same-sex partner. A small number of participants (≤ 5) self-identified as transgendered or having both female and male partners; however, as subgroup analyses were conducted across gender, these participants were excluded from analysis because of the small sample size.

The health status of participants involved in our study varied (Table 1). The majority of participants identified themselves as currently in good health (63%). Participants reported a wide distribution of active medical conditions including: cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, mental health issues, and cancer. Arthritis and cardiovascular disease were the most frequently reported chronic medical conditions (42% and 34%, respectively).

Table 1: Demographics of participants

Note. * Percentage of gender. MRP = most responsible provider.

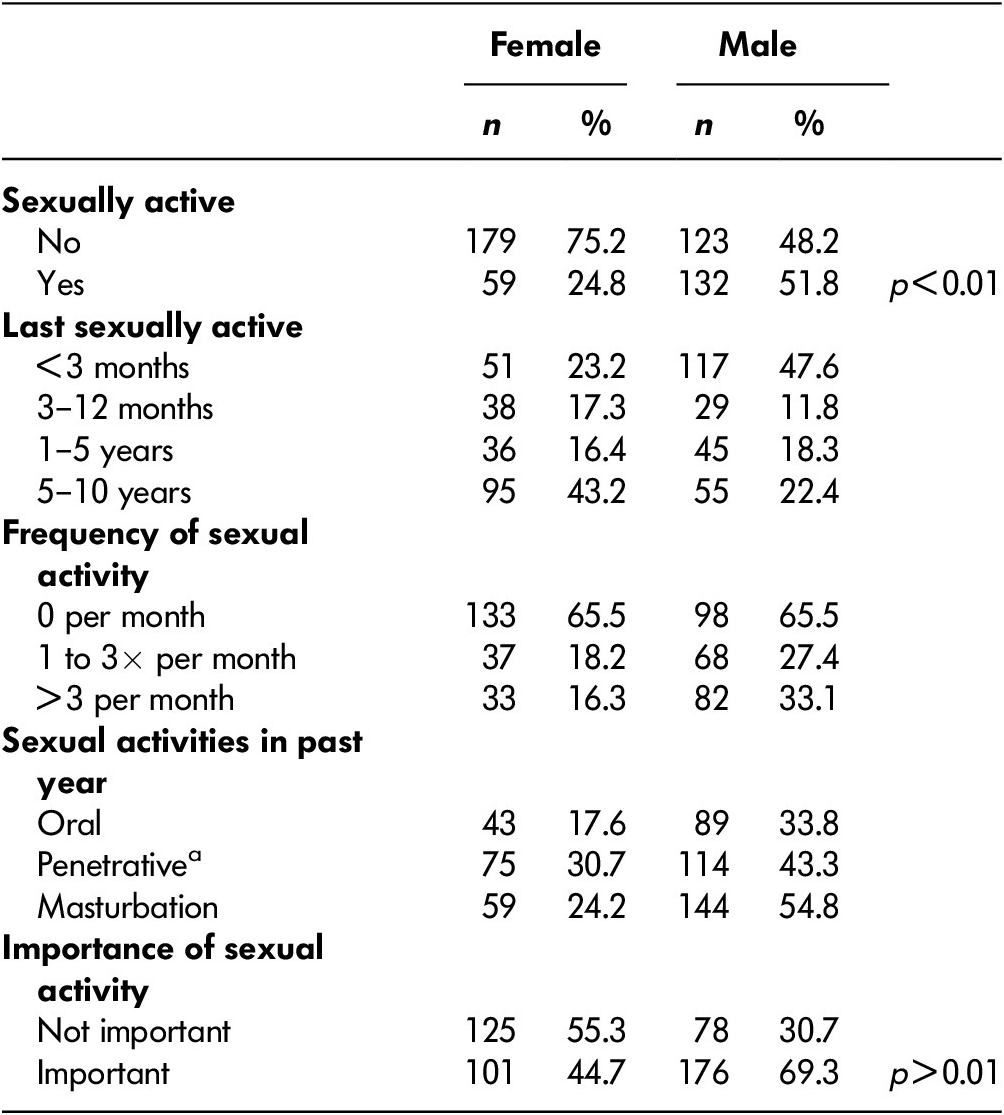

Thirty-nine percent of participants overall indicated that they were sexually active; 52 per cent of males reported being sexually active as compared with 25 per cent of females (p < 0.01). Males were more likely than females to report that sexual activity was important (69% vs. 45%, p < 0.01) (Table 2). For females, the majority identified vaginal atrophy, partner-related concerns, physical health, and dyspareunia as sexual health issues, whereas the leading sexual health issues identified by males were erectile dysfunction and partner-related concerns (Figure 1). More female participants than male participants identified pain with intercourse or dyspareunia to be an active sexual health problem. Male participants more often identified anxiety, issues with their partner, and sexually transmitted infection (STI) risk as active sexual health concerns.

Figure 1: Active sexual health issues of female and male participants

Table 2: Sexual activity of participants

a Penetrative includes vaginal and anal intercourse.

Fishers two tailed p < 0.01.

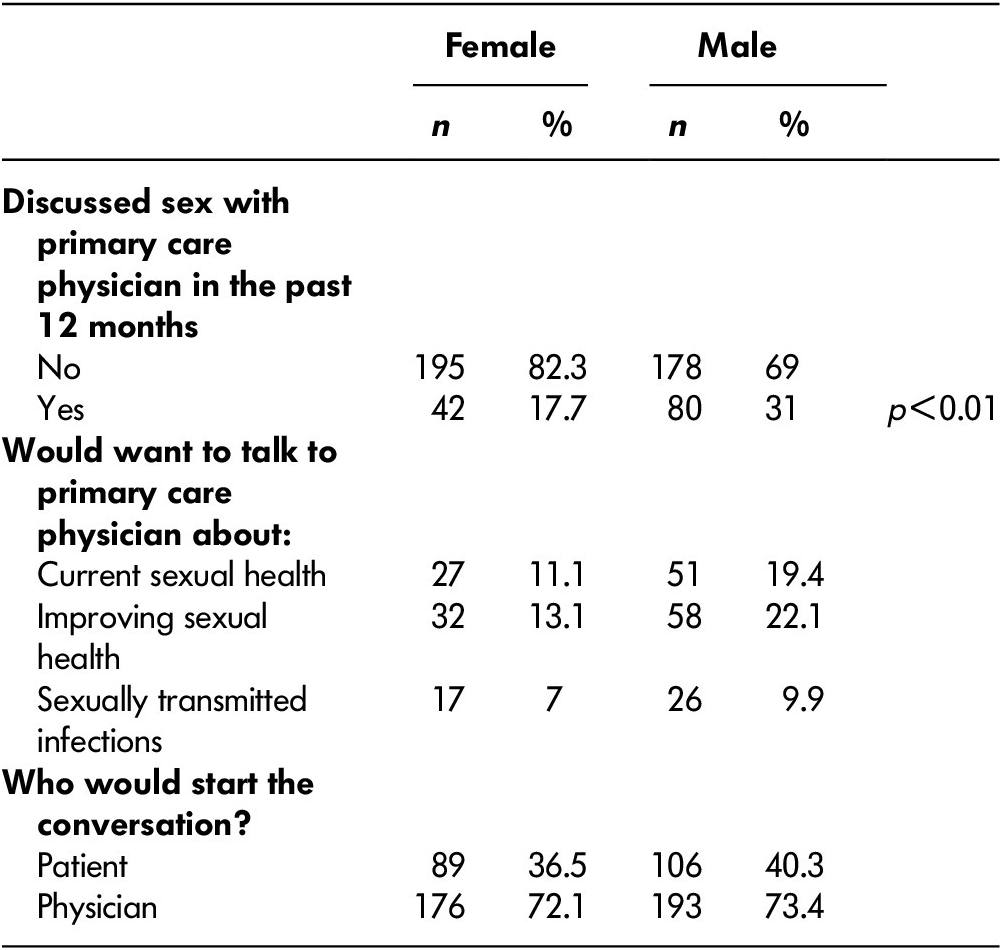

There was no significant difference between male and female participants in terms of discussing their physical sexual health issues (vaginal atrophy, bleeding, erectile dysfunction, or premature ejaculation) with their physician. Participants who identified ongoing sexual health problems were more likely to discuss with their physician physical dysfunctions (erectile dysfunction, vaginal dryness or atrophy, dyspareunia, premature ejaculation, or STI risk) than emotional, social, or global health-related issues (p < 0.01, Figure 2). Seventeen per cent of male participants and 16 per cent of female participants reported that they avoided sexual activity because of the sexual health problems that they experienced.

Figure 2: Active sexual health issues discussed with doctor

Male participants were more likely to have discussed a sexual health problem with their family physician than were female participants (Table 3, p < 0.01). Both males (73%) and females (72%) reported a preference that their physicians, as opposed to themselves, initiate a conversation about their sexual well-being.

Table 3: Conversations between patients and their primary care physician

Fishers two tailed p < 0.01.

Discussion

The results of our study suggest that approximately 40 per cent of adults over the age of 50 in our study population have ongoing sexually activity. Consistent with data from the United States, the overall prevalence of sexual activity amongst women is less than for men in this age group (Lindau & Gavrilova, Reference Lindau and Gavrilova2010). Sexual inactivity appears to be coupled with a lack of interest. In an American study addressing sexual health activity in women and men between 57 and 85 years of age, women consistently rated sex as being “not at all important” (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). This is consistent with our data in which women were also found to be more likely than men to report sexual activity as being unimportant. We propose that disparity in sexual activity between men and women is correlated with perceived importance, as women in our study self-reported sexual activity to be less important than men did. This is supported by other studies, which show women rating sexual activity to be less important than men do, as well as having overall less sexual activity (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). However, the underlying etiology of the difference in gender-reported importance requires further clarification to determine causation.

Gender-specific physical sexual health concerns such as vaginal atrophy and dyspareunia in females and erectile dysfunction in males were frequently reported by study participants and are similar to findings quoted in other studies (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007; Waite, Laumann, Das, & Schumm, Reference Waite, Laumann, Das and Schumm2009). Reporting of these symptoms is not unexpected, considering the physiologic changes that occur in men and women as they age. Given the age of our study population, the majority of females were likely peri-menopausal or post-menopausal. With the development of a hypo-estrogenic state, issues such as vaginal atrophy become more common (Leiblum, Bachmann, Kemmann, Colburn, & Swartzman, Reference Leiblum, Bachmann, Kemmann, Colburn and Swartzman1983; Sturdee & Panay, Reference Sturdee and Panay2010). Although there are many factors implicated in the development of erectile dysfunction, the burden of cardiovascular risk factors in aging men may be reflected in the increased reporting of this associated condition (Braatvedt, Reference Braatvedt2003; Sturdee & Panay, Reference Sturdee and Panay2010).

We found that males and females were more likely to discuss with their physician physical symptoms rather than global health and psychosocial issues that they also perceived to impact ongoing sexual function. This disparity may be related to physician-led inquiry into symptoms. For example, a periodic health review or investigative workup for cardiovascular disease or diabetes often includes a discussion of erectile dysfunction, as many men begin to experience symptoms of erectile dysfunction as a consequence of these ailments (Bella, Lee, Carrier, Bénard, & Brock, Reference Bella, Lee, Carrier, Bénard and Brock2015; Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee, 2013; Daskalopoulou et al., Reference Daskalopoulou, Rabi, Zarnke, Dasgupta, Nerenberg and Cloutier2015; Nehra et al., Reference Nehra, Jackson, Miner, Billups, Burnett and Buvat2012). When considering indications for osteoporosis screening, physicians will often ask women about symptoms of menopause (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Nevitt, Browner, Stone, Fox and Ensrud1995; Papaioannou et al., Reference Papaioannou, Morin, Cheung, Atkinson, Brown and Feldman2010). Some of the early indicators of potentially compromised bone health, in addition to menstrual irregularity, include symptoms suggestive of a hypo-estrogenic state: vasomotor disturbances, vaginal dryness, and impaired lubrication (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings, Nevitt, Browner, Stone, Fox and Ensrud1995; Van der Voort, Geusens, & Dinant, Reference Van der Voort, Geusens and Dinant2001). Therefore, physician patterns of behaviour with respect to screening for common chronic medical conditions may be an important factor that increases the likelihood of detecting and discussing physical sexual health complaints. Although males and females both regularly cited sexual health problems that were caused by external factors—partner-related concerns, STI risk, and anxiety—it is perhaps not surprising that a conversation relating to global health and psychosocial concerns that impact sexual function was reported less often by participants. Outside of sexual health, physicians tend to appreciate the importance of considering social determinants and the impact that these have on overall well-being. Furthermore, physicians generally report a lack of confidence in addressing sexuality, and as such, it is a subject that is often overlooked in medical visits (Fenton, 2011; Lightman, Mitchell, & Wilson, Reference Lightman, Mitchell and Wilson2008). Although there are some data that underscore the impact of topics such as partner interest, anxiety, and grief in the context of ongoing illness (Halley, May, Rendle, Frosch, & Kurian, Reference Halley, May, Rendle, Frosch and Kurian2014; Hart et al., Reference Hart, Coon, Kowalkowski, Zhang, Hersom and Goltz2014; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Patel, Saxena, Maj, Maselko, Phillips and Rahman2007), the impact of psychosocial issues on sexual health remains under-reported in the literature. Further research underscoring the impact of psychosocial issues, and how primary care providers can integrate them into a discussion about sexual health, is needed.

Males were more likely than females to discuss their sexual health concerns with their primary care providers, but it is unclear as to whether this is reflective of physician or patient comfort in addressing sexual health needs. Lindau et al. (Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007) also found that despite a similarly high prevalence of sexual problems in men and women, women were less likely to have discussed sex with a physician, citing negative societal attitudes about mature female sexuality as a potential contributing factor (Lindau et al., Reference Lindau, Schumm, Laumann, Levinson and O’Muircheartaigh2007). In a study exploring the sexual health content of periodic health examinations, sexual health discussions were found to occur more frequently with women than men (Ports et al., Reference Ports, Barnack-Tavlaris, Syme, Perera and Lafata2014). However, conversations with women revolved around cervical cancer screening, whereas with men, sexual performance was more often the focus. Female sexual performance discussions were more frequently initiated by patients, but given that patients are less likely to initiate discussions, these concerns are more likely to go undetected in females as they age. Overall, both men and women indicated a preference for physician-initiated discussions about sexual health as opposed to self-initiated ones. Similar results have been reported in other studies exploring physician–patient discussions about sexual health (Ports et al., Reference Ports, Barnack-Tavlaris, Syme, Perera and Lafata2014). Mature patients see their primary care provider as the most appropriate professional with whom to discuss their sexual problems and rarely initiate the discussion themselves (Gott & Hinchliff, Reference Gott and Hinchliff2003). As such, if physicians do not inquire, many sexual health issues may persist undetected (Ports et al., Reference Ports, Barnack-Tavlaris, Syme, Perera and Lafata2014). This supports the notion that patients do feel it is within the scope of care provided by their family physician to take the initiative to investigate and provide counsel when necessary regarding sexual health in this age group.

We achieved a high response rate (63%) among a diverse group of participants. Participants were able to anonymously report their sexual health behaviours and issues in a confidential setting, allowing for a candid expression of their sexual health needs. However, several limitations should be noted when interpreting these findings. The generalizability of our results may be limited, as the study was conducted at one centre reflecting an inner-city population. The social determinants of health impacting our urban population may not be generalizable to older adults in other environmental settings. Our study did not a priori define the term “sexual activity”, and in turn, left the interpretation up to the survey respondent. The generalizability as to how this term was interpreted would be specific to the study participant. However, in discussion with patients, providers often use generalizable terms including asking “are you sexually active” and then the patient can clarify as appropriate. Future research could aim to clarify how sexual activity is defined by adults as they age.

Another limitation surrounds the use of surveys for information gathering. As with any survey-based study, we are relying on patients to accurately self-report, which may or may not be reliable. Given the sensitive nature of the subject, some patients may have elected to not complete certain sections or questions in the survey. In addition, most patients (83%) in our study had seen their primary care provider in the last 12 months, and therefore may represent a population that is particularly vigilant about their health overall, providing more opportunity to explore issues concerning their sexual health. However, 8 out of 10 Canadian seniors rate their health as excellent, very good, or good (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018), which is reflective of the measure of self-rated health expressed by the participants of our study. As such, we believe that our findings may be reflective of attitudes of other Canadian seniors. Finally, ideas about what is included in the definition of sexual activity may vary from person to person. For example, some participants may define sexual activity as only that which occurs with a partner or involves penetrative intercourse, and others may include masturbation in their definition. In addition, the list of sexual health problems included as potential responses in the survey may not have adequately captured all concerns.

In conclusion, the results of our study indicate that men, more so than women, continue to be sexually active past the age of 50. Common sexual health problems that can lead to avoidance of sexual activity include both physical and non-physical concerns, although physical concerns are more frequently discussed with physicians. Sexual health care among adults over 50 years of age may be improved through provider-initiated discussions, as both men and women prefer that their family physicians initiate discussions regarding sexual health.

Given the relatively under-studied nature of sexual health in Canadians over 50 years of age, there are many areas that remain to be explored in this realm of research. Future directions of particular relevance to our study include exploring physician perspectives on addressing sexual health in patients over 50 years of age and factors that may inhibit or permit open discussion about sexuality between patients and their primary care providers.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0714980819000734.