Childhood is a critical period in the development of obesity(Reference Simmonds, Llewellyn and Owen1). Parents are responsible for the food environment and eating experiences for their children(Reference Scaglioni, Salvioni and Galimberti2,Reference Larsen, Hermans and Sleddens3,Reference Anzman, Rollins and Birch4) . Feeding strategies used by parents aiming to control or modify their child food intake have been the focus of several research studies(Reference Blaine, Kachurak and Davison5–Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10). A relationship between parental feeding practices and the food consumption(Reference Blaine, Kachurak and Davison5,Reference Yee, Lwin and Ho6) , eating behaviours(Reference Jansen, Williams and Mallan7,Reference Steinsbekk, Belsky and Wichstrøm8,Reference Rodgers, Paxton and Massey11) and weight(Reference Spill, Callahan and Shapiro9,Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10) of children has been suggested. In particular, controlling or restrictive feeding practices are potentially problematic and can be associated with obesogenic eating behaviours and less healthy food consumption(Reference Blaine, Kachurak and Davison5,Reference Yee, Lwin and Ho6,Reference Steinsbekk, Belsky and Wichstrøm8,Reference Rodgers, Paxton and Massey11) .

Parental feeding practices are influenced by many factors, such as the family’s socio-economic and psychological characteristics, as well as parental perceptions of those characteristics(Reference Steinsbekk, Belsky and Wichstrøm8,Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10,Reference Power, Hughes and Goodell12–Reference Mcphie, Skouteris and Daniels14) . Specifically, previous research has shown that maternal perceptions or concerns with their children’s weight influence feeding practices(Reference May, Donohue and Scanlon13,Reference Crouch, O’dea and Battisti15–Reference de Lauzon-Guillain, Musher-Eizenman and Leporc21) . In toddlers, pre-schoolers and school-aged children, maternal concern about future child overweight was cross-sectionally associated with restrictive feeding practices, while concern about underweight was associated with pressure to eat(Reference Harrison, Brodribb and Davies17,Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke19,Reference Haines, Downing and Tang20,Reference Gregory, Paxton and Brozovic22) . There is considerable evidence that mothers misjudge their child weight status. In general, mothers tend to underestimate their child’s weight status, failing to recognise excessive weight(Reference Parkinson, Reilly and Basterfield23,Reference Queally, Doherty and Matvienko-Sikar24) . Mothers who perceive their child as having overweight/obesity report higher levels of restriction and lower levels of pressure to eat(Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke19,Reference Francis, Hofer and Birch25–Reference Lydecker and Grilo27) . On the other hand, mothers who perceive their child as underweight are more likely to pressure their child to eat more(Reference Harrison, Brodribb and Davies17,Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke19,Reference Francis, Hofer and Birch25,Reference Lydecker and Grilo27) .

As maternal feeding practices are modifiable risk factors for problematic child diet-related outcomes, understanding their underlying factors may offer valuable insights for tailored interventions to improve child health. To our knowledge, studies have evaluated the association between maternal perception of weight and feeding practices at one time point and with children from a broad age range, thereby it makes it difficult to explore age differences and effects of time. A further topic rarely researched is the stability of maternal perception and concern across time. Additionally, most studies have relied on relatively small sample sizes(Reference May, Donohue and Scanlon13,Reference Crouch, O’dea and Battisti15–Reference de Lauzon-Guillain, Musher-Eizenman and Leporc21,Reference Tang, Ji and Zhang28,Reference Damiano, Hart and Paxton29) , and only a few have evaluated weight perception and concern about child weight simultaneously(Reference Ek, Sorjonen and Eli16,Reference Harrison, Brodribb and Davies17,Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke19) . Weight perception might not influence feeding practices unless parents are also concerned about their child weight, so it is crucial to study these concepts in tandem. Furthermore, a concept that is often neglected is the extent to which mothers are dissatisfied with their child body weight. Parents’ dissatisfaction with child weight occurs when they believe that the child is above or below an idealised weight(Reference Hager, Candelaria and Latta30,Reference Weinberger, Kersting and Riedel-Heller31) . The concept of dissatisfaction is multidimensional and is related to perceptions and concerns about weight, but it is distinct. For example, a mother may be concerned about their child becoming overweight but satisfied with current weight status. Mothers who are dissatisfied with their own weight appear to use more controlling feeding practices(Reference Webb and Haycraft32), but the direct relationship between maternal dissatisfaction with child weight and feeding practices is less well understood. Overall, since the mother is principally responsible for what and how a child is fed in the early years, it is important to consider how her perceptions and concerns about child weight might influence the ways in which she feeds her child.

Therefore, using data from a large population-based prospective cohort, the aim of the present investigation was to examine the association between maternal perception, concern and dissatisfaction with child weight and feeding practices (monitoring, pressure to eat, restriction, overt control and covert control) at two time points (at 4 and 7 years of age). Our secondary aim was to analyse the stability of maternal cognitions about child weight from 4 to 7 years of age. We hypothesised that mothers who perceive their children as having overweight and who are concerned or dissatisfied with their child weight would report more restrictive and controlling feeding practices.

Methods

Study population

This study included participants from a population-based birth cohort Generation XXI, described elsewhere(Reference Larsen, Kamper-Jørgensen and Adamson33,Reference Alves, Correia and Barros34) . A total of 8647 liveborn infants were enrolled between April 2005 and August 2006 in all level III public maternity wards from the metropolitan area of Porto (northern Portugal). All families were invited to attend evaluations when children were aged 4- and 7 years (86 % and 80 % participation proportion, respectively). The present study included all children who attended both evaluations (n = 6647). Twins (n = 283) and children with missing information on variables of interest (i.e., maternal feeding practices, weight perception and concern about weight gain and potential confounders) were excluded (n 3414), resulting in a final sample of 3233. The inclusion and exclusion flowchart of participants is available in Fig. 1. Comparison of baseline characteristics between this sample and the remaining cohort (non-participants) showed that mothers in the present sample were slightly older (mean = 29·2 years; sd = 5·7 compared with 29·9 years; sd = 5·0) and more educated (mean = 10·0 complete schooling years; sd = 4·2 compared with 11·8 complete schooling years; sd = 4·2). According to Cohen‘s effect size values(Reference Husted, Cook and Farewell35), the magnitude of differences was not high (0·13 for maternal age and 0·42 for maternal education).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of participants selection.

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving were approved by the Ethical Committee of São João Hospital/University of Porto Medical School and by the Portuguese Authority of Data Protection. Legal representatives of each participant received an explanation of the purposes and design of the study and gave written informed assent at baseline and each follow-up assessment.

Measures

Feeding practices

Feeding practices were measured using maternal self-report when their child was aged 4 and again at age 7 years. A combined version of the original Child Feeding Questionnaire(Reference Birch, Johnson and Fisher36) and the scales of overt and covert control devised by Ogden et al were used(Reference Ogden, Reynolds and Smith37). This version was previously adapted and validated for Portuguese preschool children from Generation XXI(Reference Real, Oliveira and Severo38). At 7 years of age, this adapted version showed also a good fit, as well as a fair to moderate reproducibility(Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10). Maternal feeding practices included the following subscales: restriction (the extent to which parents control the child’s access to foods or opportunities to consume those foods) (three items), pressure to eat (parents’ insistence or demands that their children eat more food) (four items), monitoring (the extent to which parents track what and how much the child is eating) (three items), overt control (represented by a firm attitude from parents about what, how much, where, and when the child eats, which can be perceived by the child) (five items), and covert control (in which the child is unable to detect the control; for example, avoiding buying energy-dense foods) (four items). Answers were given on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher levels in each subscale. In our sample, at both time points, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each subscale were calculated to assess the internal consistency, at 4 years of age ranged from 0·69 to 0·89 and at 7 years ranged from 0·71 to 0·89.

Maternal perception of child current weight and concern about child weight gain

Perception of child current weight status was assessed at both ages by a single question: ‘How would you describe your child’s weight currently?’, with response options of: ‘Very underweight,’ ‘Underweight’, ‘Normal weight’, ‘Overweight’ and ‘Very overweight’. Further, due to the relatively low sample size in the two extreme categories, ‘Very underweight’ (n = 16 at 4 years n = 20 at 7 years) and Very Overweight (n = 14 at 4 years and n = 20 at 7 years), these categories were combined with ‘Underweight’ and ‘Overweight’, respectively. Concern about child weight gain was assessed using the item: ‘How concerned are you about your child becoming overweight?’, with response options of: ‘Not concerned’, ‘A little concerned’, ‘Concerned’, ‘Quite concerned’, ‘Very concerned’. Responses were dichotomised into ‘unconcerned’ and ‘concerned’ (a composite score across a little concerned, concerned, quite concerned, very concerned). Both items were derived from the Child Feeding Questionnaire(Reference Birch, Johnson and Fisher36), which was tested in our sample (as previously described)(Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10,Reference Real, Oliveira and Severo38,Reference Real, Oliveira and Severo38) .

Satisfaction with child body weight

Maternal satisfaction with child body weight was evaluated at 4 years of age by a single question: ‘Do you think that the weight of your child is adequate for his/her age and height?’ with response options of: ‘No, my child should weigh more’, ‘No, my child should weigh less’, ‘Yes’. At 7 years of age, mother’s satisfaction with child body size was assessed using a figure rating scale(Reference Rand and Resnick40). Mothers were presented with nine gender-specific figures of increasing size, each designated with a numerical rating. Mothers indicated the figure that they felt best reflected their child’s current body size and their child’s ideal body size. Satisfaction with child body size was calculated as the silhouette number indicated as ideal subtracted from the silhouette number indicated as current (perception); a negative score indicated that mothers considered that their child should weigh more; a zero represented satisfaction with child body size; a positive score indicated that mothers considered that their child should weigh less. These scores were recoded into three categories of response to be comparable to the question applied at age 7 years: ‘should weigh less’, ‘should weigh more’, ‘about right’.

Co-Variates

Anthropometric measurements were performed by trained staff using standard procedures(Reference Gibson41). Children’s BMI was classified according to the age- and sex-specific BMI standard z-scores developed by the WHO(Reference De Onis, Onyango and Borghi42). The WHO cut-offs for weight status categories differ for children 0–5 years old and 5–19 years old. In the current sample, given the proximity of children’s age to 5 years, the same cut-offs were used for children at 4 and 7 years, i.e., underweight (–≤ 2 sd), normal weight (–2 sd to –1 sd), overweight (1 sd to –2 sd) and obese (≥ 2 sd). Overweight and obese categories were collapsed for data analysis. Waist:height ratio was calculated as waist circumference divided by height. Clinical records were reviewed at birth to retrieve data on birth weight. Country of birth of the mothers was assessed as an open question and transformed into a categorical variable (Portuguese; non-Portuguese). Maternal BMI was defined as weight in kilograms divided by squared height in metres. Maternal age and education were recorded as completed years of ageing and schooling. Household monthly disposable income was collected as a categorical variable (< 500, 500–1000, 1001–1500, 1501–2000, 2001–2500, 2501–3000, and > 3000 euros) and further grouped into four ordinal categories.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics are presented as means and standard deviations (sd) for continuous data, or numbers and percentages for categorical data. To assess the stability of maternal variables from 4 to 7 years of age kappa coefficients were calculated(Reference Landis and Koch43). McNemar’s or Bowker’s test was used to assess change in proportions over time. The association of maternal weight perception, concern about child weight gain and dissatisfaction with child body weight (independent variables) with feeding practices (dependent variables) were estimated by linear regression models. Statistical significance and 95 % CI were described using Bonferroni‘s correction. An alpha(α) of 0·01 (α = 0·05/5) was used. Several potential confounders were individually assessed in each model, but those that did not change the magnitude of the associations of interest were not included in final analyses (maternal age, country of birth of the mother, maternal BMI, birth weight and household income). Two different models for each feeding practice are presented: the first model shows the unadjusted results (model 1); the second model, considered as the final model, included all maternal cognitions about weight (perception, concern and dissatisfaction), plus maternal education, child sex and BMIz at 4 or 7 years of age (model 2). Interaction of the child sex in these associations was tested by including an interaction term in the final models, but no significant interaction was found. Thus, results are reported for all children. The consistency between the exposure variables (maternal perception, concern and dissatisfaction with child weight) was also assessed to see if a unique construct would be feasible to calculate, but the Cronbach-alpha of 0·263 at 4 and 0·290 at 7 did not support that, so they were treated as separate concepts.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS statistical software package version 26 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

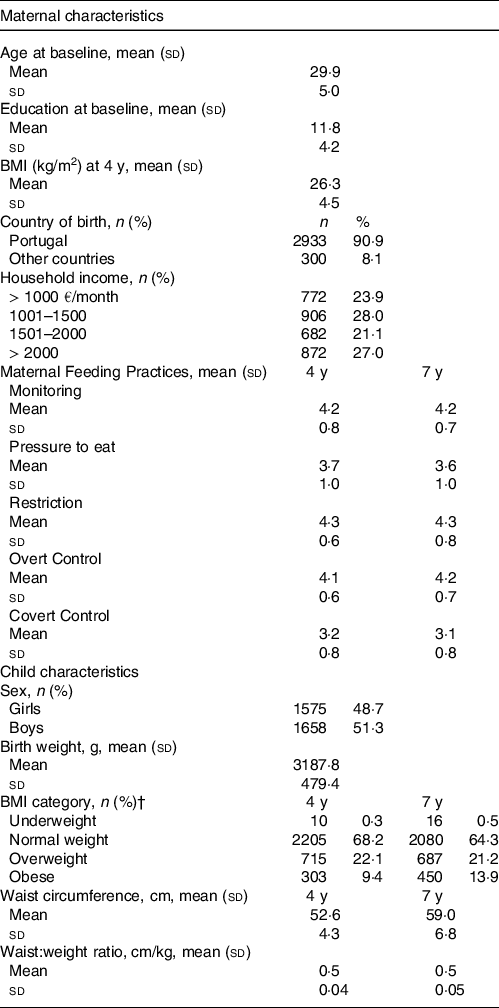

Characteristics of mothers and their children are presented in Table 1. The mean age of mothers at baseline was 29·9 years, their mean education was 11·8 complete schooling years and their mean BMI at 4 years of age follow-up was 26·3 kg/m2. Fifty-one per cent of children were boys, and the percentage of children with overweight or obesity slightly increased from 4 to 7 years of age (from 31·5 % and 35·1 %, respectively).

Table 1. Mothers‘ and child‘s characteristics at the 4 years and 7 years follow-up

(mean values and standard deviations, n = 3233)

zBMI, BMI z-score; y, years old.

† Child weight status was classified according to the WHO criteria(Reference De Onis, Onyango and Borghi42).

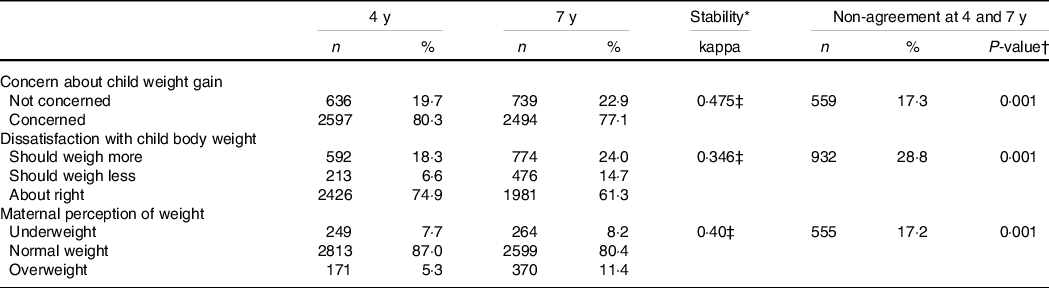

At both ages, about 80 % of the mothers reported that they were concerned that their child would become overweight (Table 2). The agreement between answers at 4 and 7 years of age was moderate (k = 0·475, P < 0·001); only 17 % of mothers changed their view. Regarding dissatisfaction with child body weight at 4 years of age, 75 % of mothers were satisfied and only 7 % considered that their child should weigh less. At 7 years of age, a higher percentage of mothers desired a larger (24 %) or slimmer body size (15 %) for their child. There was a slight, but significant, agreement between classifications at 4 and 7 years (k = 0·346, P < 0·001), with almost 30 % reporting a change in their level of satisfaction. Maternal concern and dissatisfaction with child weight by weight category of the child are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 2. Maternal perception, concern and dissatisfaction with child weight

(Numbers and percentages, n = 3233)

* The values represent kappa coefficients.

† McNemar McNemar’s or Bowker’s Test to test if the answers change significantly from 4 to 7 years of age.

‡ Statistically significant results (P < 0·001).

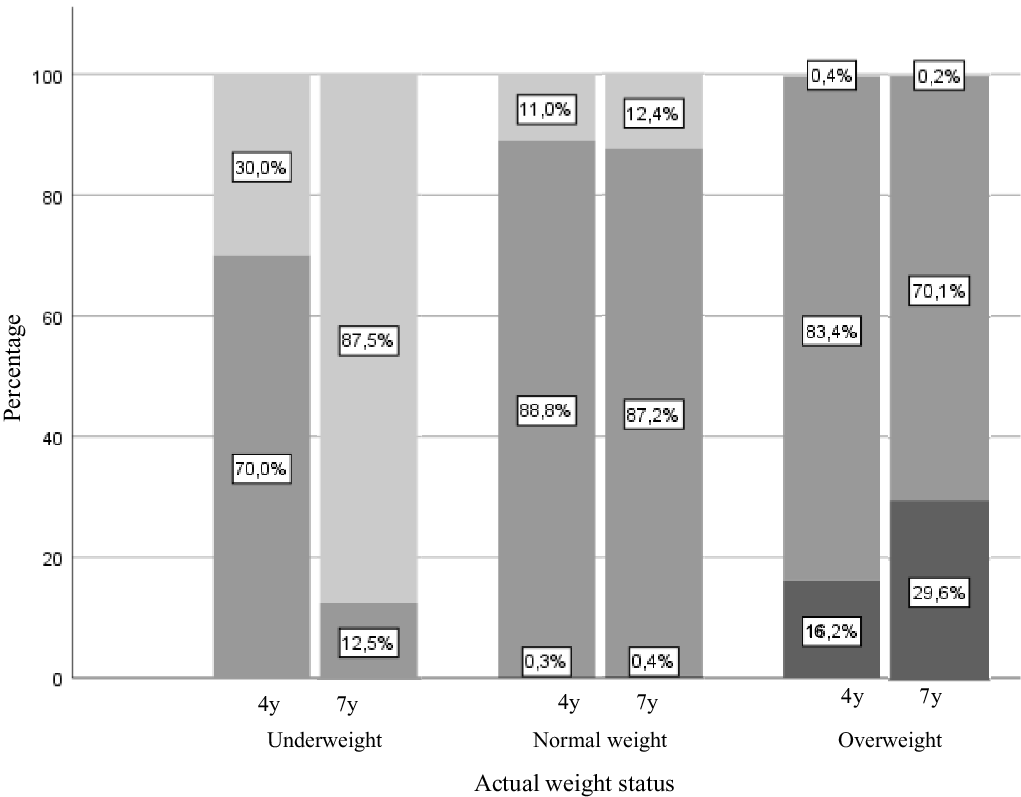

Most mothers rated their child as having a normal weight (87 % at 4 years old and 80 % at 7 years old), and moderate agreement was observed between classifications across time (k = 0·404, P < 0·001). Figure 2 shows that at 4 years of age, 83 % of mothers whose child had overweight did not identify this in their child. This percentage decreased to 70 % by 7 years of age.

Fig. 2. Maternal weight perception and actual weight status ate 4 and 7 years of age (n = 3233). Child weight status was classified according to the WHO criteria(Reference De Onis, Onyango and Borghi42). ![]() , Underweight;

, Underweight; ![]() , normal;

, normal; ![]() , overweight

, overweight

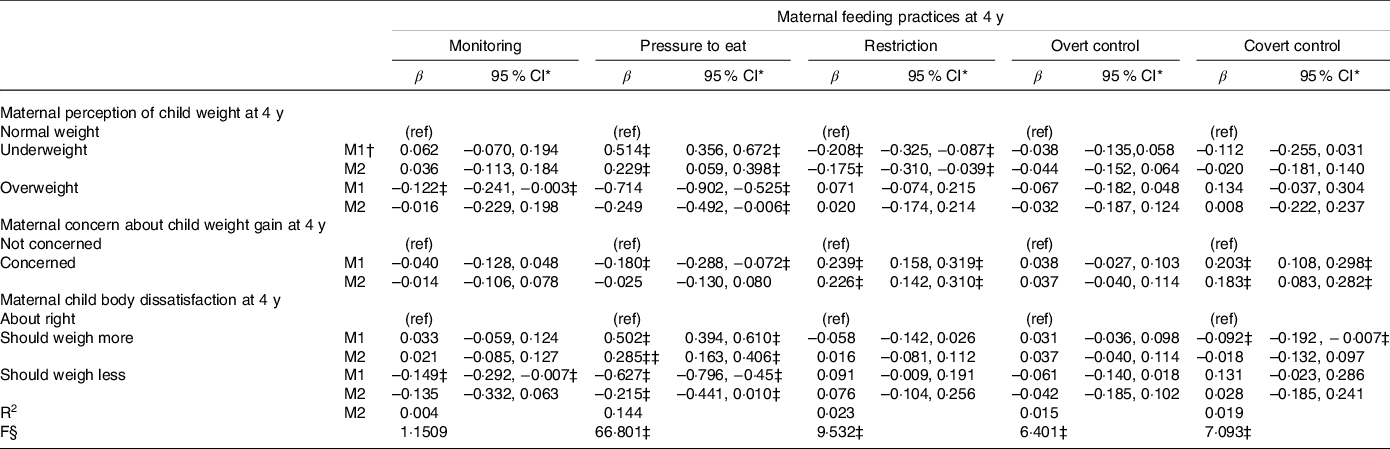

Table 3 presents the results of the associations between maternal perception, concern and dissatisfaction with child weight and maternal feeding practices at 4 years of age, and Table 4 shows the same associations three years later. The comparison of mean scores of feeding practices across cognitions on child weight is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1, 2 and 3. Mean scores differed significantly between weight perception categories for all feeding practices, except monitoring and overt control at 4 years (online Supplementary Fig. 1). Most significant differences were found in children classified as underweight and normal weight compared with those classified as overweight. In multivariate analysis (model 2 fully adjusted), mothers who rated their child weight status as underweight reported significantly higher levels of pressure to eat at both 4 and 7 years of age (β = 0·229; 95 % CI: 0·059, 0·398 and β = 0·190; 95 % CI: 0·005, 0·376, respectively), and lower restriction at 4 years of age (β = –0·175; 95 % CI: –0·310, –0·039), compared to mothers who rated their child’s weight status as normal. Conversely, perceived child overweight was associated with lower levels of pressure to eat at 4 years (β = –0·249; 95 % CI: –0·492, –0·006). At 7 years of age, mothers who rated their child as overweight also reported significantly higher levels of covert control (β = 0·203; 95 % CI: 0·029, 0·376).

Table 3. Associations between maternal perception, concern and dissatisfaction with child weight and maternal feeding practices at 4 years old

(Coefficient values and 95 % confidence intervals, n = 3233)

y, years of age; ref, reference category; R2, variance explained by the model.

* 95 % CI with Bonferroni’s correction.

† M1: unadjusted model, M2: model includes perception, concern and dissatisfaction about weight, plus maternal education, child sex and zBMI at 4 years of age.

‡ Statistically significant associations.

§ F (8,3224) for the models.

Table 4. Associations between maternal perception, concern and dissatisfaction with child weight and maternal feeding practices at 7 years old

(Coefficient values and 95 % confidence intervals, n = 3233)

y, years of age; ref, reference category; R2, variance explained by the model.

* 95 % CI with Bonferroni’s correction.

† M1: unadjusted model, M2: model includes perception, concern and dissatisfaction about weight, plus maternal education, child sex and zBMI at 7 years of age.

‡ Statistically significant associations.

§ F (83 224) for all models.

Regarding concern about child weight gain, concerned and non-concerned mothers had significantly different mean scores for all feeding practices, except monitoring and overt control (online Supplementary Fig. 2). Comparable associations were observed at both ages, mothers who rated themselves as concerned about their child becoming overweight reported higher levels of restriction (β = 0·226; 95 % CI: 0·142, 0·310 and β = 0·261; 95 % CI: 0·169, 0·353) and covert control (β = 0·183; 95 % CI: 0·083, 0·282 and β = 0·171; 95 % CI: 0·073, 0·269).

The mean scores of most maternal feeding practices differed significantly according to their satisfaction with child weight (online Supplementary Fig. 3). Mean scores for monitoring and covert control at age 4 differed significantly only between mothers who thought their child should weigh less and those who thought their child should weigh more (higher monitoring and lower covert control). At age 7, mean scores for monitoring, restriction and covert control differed significantly only between the ‘should weigh less’ group compared with the ‘about right’ and ‘should weigh more’ groups (these groups had a higher mean score for monitoring and a lower one for restriction and covert control). At 4 and 7 years of age, mothers who thought their child should weigh more reported higher levels of pressure to eat (β = 0·285; 95 % CI 0·163, 0·406 and β = 0·393; 95 % CI: 0·266, 0·520, respectively) compared with mothers who were satisfied with their child’s body weight. On the other hand, mothers who thought their child should weigh less reported higher covert control at 7 years of age (β = 0·158; 95 % CI: 0·001, 0·316).

Discussion

Our results suggest that maternal perceived weight, concern for excess weight gain and dissatisfaction with child weight are all associated with feeding practices and that these associations were different according to the type of feeding behaviour and child age. Secondly, it suggests moderate stability of perceptions, concerns and dissatisfaction with child weight over time, and a clear maternal underestimation of child overweight.

In this study, most mothers rated their child as having a normal weight, including mothers of children with overweight or obesity. However, the underestimation of weight was lower by age 7. Parental misperception of child weight has been extensively reported; a meta-analysis found that a large proportion of parents underestimated the weight of their overweight/obese children with more accurate ratings over time(Reference Lundahl, Kidwell and Nelson44). There are many reasons for misperception of child weight status. For instance, parents can be reluctant to label their child as overweight because of social pressure to maintain a lower weight and the stigma attached to obesity. Another possible explanation is that with increasing rates in childhood obesity, an upward shift in weight norms has occurred(Reference Hansen, Duncan and Tarasenko45). Although the underestimation of child weight status was very high, a higher number (almost 80 %) of the mothers were concerned about child weight gain in future, which is consistent with prior research(Reference May, Donohue and Scanlon13,Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke19,Reference Crawford, Timperio and Telford46,Reference Regber, Novak and Eiben47) . This suggests that whilst mothers may not identify their child as overweight/obese they are nonetheless aware of the consequences of excess weight gain and express concern about this. Additionally, most mothers were satisfied with their child’s body weight, which corroborates previous literature(Reference Duchin, Marin and Mora-Plazas48).

At both ages, mothers tended to report more frequent use of pressure to eat when they perceived their child as having underweight or considered that the child should weigh more. In contrast, at 4 years old, those who perceived their child as having overweight reported lower levels of pressuring practices. Associations between weight perception and this feeding practice have been widely reported(Reference Harrison, Brodribb and Davies17,Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke19,Reference Hidalgo-Mendez, Power and Fisher26,Reference Lydecker and Grilo27) , but dissatisfaction with child body weight has seldom been addressed. Taken together, these findings indicate that maternal pressuring might arise because of the mother’s perception of the child as thin and the desire for a heavier child. Mothers might consider that a lower weight, which may be a biological (heritable) characteristic of the child, could compromise their healthy development and growth(Reference Brown, Pesch and Perrin49), using pressuring practices to prevent this. However, it is important to note that there are different types of pressure, this practice could also be used in response to children displaying food-avoidant eating behaviours, such as food fussiness or picky eating(Reference Cole, An and Lee50). Parents may pressure their children to eat more food in general, with the goal of increasing energy intake, or they may apply pressure on them to eat only certain foods, such as the ones they refuse. It is important to emphasize that the Child Feeding Questionnaire does not distinguish between these different types of pressure; it refers to pressure to eat in general, measuring the parents’ insistence or demands that their children eat more, using such strategies as insisting that children clean their plates and providing repeated prompts to eat(Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher51). Regardless of these distinctions, pressure to eat appears to be a counterproductive practice overall, linked to lower fruit and vegetable intake(Reference Yee, Lwin and Ho6), lower weight status(Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10), and likely reducing the willingness to consume the food pressured to eat(Reference Galloway, Fiorito and Francis52).

At age 4 years, mothers who perceived their child as having underweight applied fewer restrictions to their child’s access to foods. This agrees with the association reported for pressuring practices, suggesting that mothers are responsive to their child’s low weight and use specific feeding strategies to promote food intake.

Monitoring was not significantly associated with maternal perception, concern our dissatisfaction about weigh. Previous studies, with smaller samples (n = 210 and n = 186), also found no associations between perceived weight status and this practice(Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke19,Reference Hidalgo-Mendez, Power and Fisher26) . A study from our cohort (from 4 to 7 years of age) also concluded that children’s BMI did not predict monitoring(Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10). Other studies have described comparable results, with parents reporting similar levels of monitoring of children across different weight status(Reference Keller, Pietrobelli and Johnson53). The monitoring subscale measures how closely the mother keeps track of the number of sweets, snacks, and high-fat food her child eats(Reference Birch, Johnson and Fisher36), and may reflect the food environment the mother shares with the child, rather than being a direct response to child weight. Thus, maternal monitoring may be employed to maintain a healthy diet and what is perceived as a healthy weight rather than in response to their child’s weight.

Overt control, defined as a practice of controlling food intake that can be detected by the child (e.g., being firm about what, when, where, and how much a child eats)(Reference Ogden, Reynolds and Smith37), showed no significant association with any maternal cognition. In contrast, covert control, which refers to limiting unhealthy food intake in ways that are not perceived by the child (e.g., not going to restaurants or bringing sweets and snacks into the house)(Reference Ogden, Reynolds and Smith37), was more frequently reported by mothers who perceived their child as having overweight, those who were concerned about child weight and those who desired a thinner child. Ogden and colleagues, who developed the overt/covert control scale, found comparable results. Parents who perceived their children as heavier reported more covert control, but no association was found for overt control(Reference Ogden, Reynolds and Smith37). Studies assessing these different concepts of control with maternal cognitions about child weight are lacking. However, a study from our cohort also found that actual BMI influenced parents’ use of covert control but also found no association with overt control(Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10).

In addition to covert control, concern about child weight was also associated with higher restriction at both ages. Both practices are used by parents in an attempt to limit the child’s access to ‘unhealthy’ food and to control food intake(Reference Vaughn, Ward and Fisher51). Concern about child weight gain has been consistently related to restriction(Reference May, Donohue and Scanlon13,Reference Webber, Hill and Cooke19,Reference Haines, Downing and Tang20,Reference Gregory, Paxton and Brozovic22) ; however, covert control has been less studied(Reference Haines, Downing and Tang20). Our results also showed moderate stability of maternal perception, concern and dissatisfaction about child weight from 4 to 7 years of age. Both maternal and child factors can influence maternal cognitions. Regarding child-related factors, from early to middle childhood children experience considerable development and growth, such as the adiposity rebound, which occurs around 6 years of age(Reference Péneau, González-Carrascosa and Gusto54), and increasing autonomy in food intake. Simultaneously, at age 7 children start primary school and the comparison with their peers might also alter maternal perceptions.

Some strengths and limitations of the present study should be considered. An obvious strength is the use of a large population-based sample and standardised assessments of maternal feeding practices and maternal cognitions about child weight. Further, our study assessed overt and covert control, which has rarely been addressed to date. Additionally, many previous studies have not adjusted for child BMI, which conflates the effects of cognitions with those of actual weight status(Reference May, Donohue and Scanlon13,Reference Haines, Downing and Tang20,Reference Hidalgo-Mendez, Power and Fisher26,Reference Lydecker and Grilo27) . When actual BMI was included in the models, several associations lost statistical significance or effect size, which is not surprising given that BMI is closely related to both feeding practices and cognitions. It is also possible that some mothers might misperceive the child’s weight, not be concerned, or dissatisfied with child weight, but nevertheless be influenced by the actual weight status in feeding practices. In addition to zBMI, all maternal cognitions were also included in our models, which allowed us to assess their independent effect. With the inclusion of these variables simultaneously, some associations lost significance, such as associations with weight perception, suggesting that the observed effects were due the other cognitions. It is important to highlight that although we found several significant associations, our models explain only a small proportion of variance in maternal feeding practices (the highest value (<20 %) was found for pressure to eat). This reflects the complexity of maternal feeding practices, which are influenced by several factors, such as children eating behaviours, that were not included in the analyses. The study’s main limitation is the self-reported nature of both the maternal cognitions and feeding practices. Self-report is known to introduce some measurement error, with mothers potentially misreporting due to lack of awareness, social desirability bias, or because of inherent subjectivity. Studies comparing maternal self-reported feeding practices with independent observations of their feeding have found poor associations between the two measures(Reference Bergmeier, Skouteris and Haycraft55,Reference Lewis and Worobey56) . Nevertheless, the Child Feeding Questionnaire has been widely used and was previously validated in our sample(Reference Afonso, Lopes and Severo10). Additionally, an important point to explore in future studies is whether perceptions and concerns about child weight influence parental practices related to other behavioural factors associated with obesity, such as monitoring and controlling their child’s physical activity or sedentary behaviour.

In summary, the current research contributes to our understanding of the underlying factors influencing feeding practices. The findings suggest that, in preschool and school-aged children, mother’s perception of a child as underweight and dissatisfaction with this condition are related to feeding practices promoting food intake. However, mothers who perceived their child as having overweight did not report using more controlling feeding practices to modify their child’s food intake. Also, maternal concerns about child future weight gain are associated with feeding strategies to limit and control access to food. Additionally, moderate stability of maternal cognitions about child weight was found from 4 to 7 years of age. Despite that, some level of disagreement was found, with mothers more accurately identifying overweight/obesity over time. Clearly, it is important to evaluate maternal cognitions related to child weight, since perception, concern and dissatisfaction appear to be related to feeding practice independent of actual weight status.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the families enrolled in Generation XXI for their kindness, all members of the research team for their enthusiasm and perseverance and the participating hospitals and their staff for their help and support. We also acknowledge the support from the Epidemiology Research Unit (EPI-Unit: UID-DTP/04750/2013; POCI-01-0145-FEDER-006862).

Generation XXI was funded by the Health Operational Programme – Saúde XXI, Community Support Framework III and the Regional Department of Ministry of Health. This study was supported through FEDER from the Operational Programme Factors of Competitiveness – COMPETE and through national funding from the Foundation for Science and Technology – FCT (Portuguese Ministry of Education and Science) under the projects ‘Appetite regulation and obesity in childhood: a comprehensive approach towards understanding genetic and behavioural influences’ (POCI-01–0145-FEDER-030334; PTDC/SAU-EPI/30334/2017); ‘Appetite and adiposity – evidence for gene–environment interplay in children’ (IF/01350/2015), and through Investigator Contract (IF/01350/2015 – Andreia Oliveira). It had also support from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

A. C. performed the statistical analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. A. O. contributed to the design of the study, the interpretation of data and revised the manuscript. M. H. contributed to the interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

There are no conflicts of interest

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521001653