No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

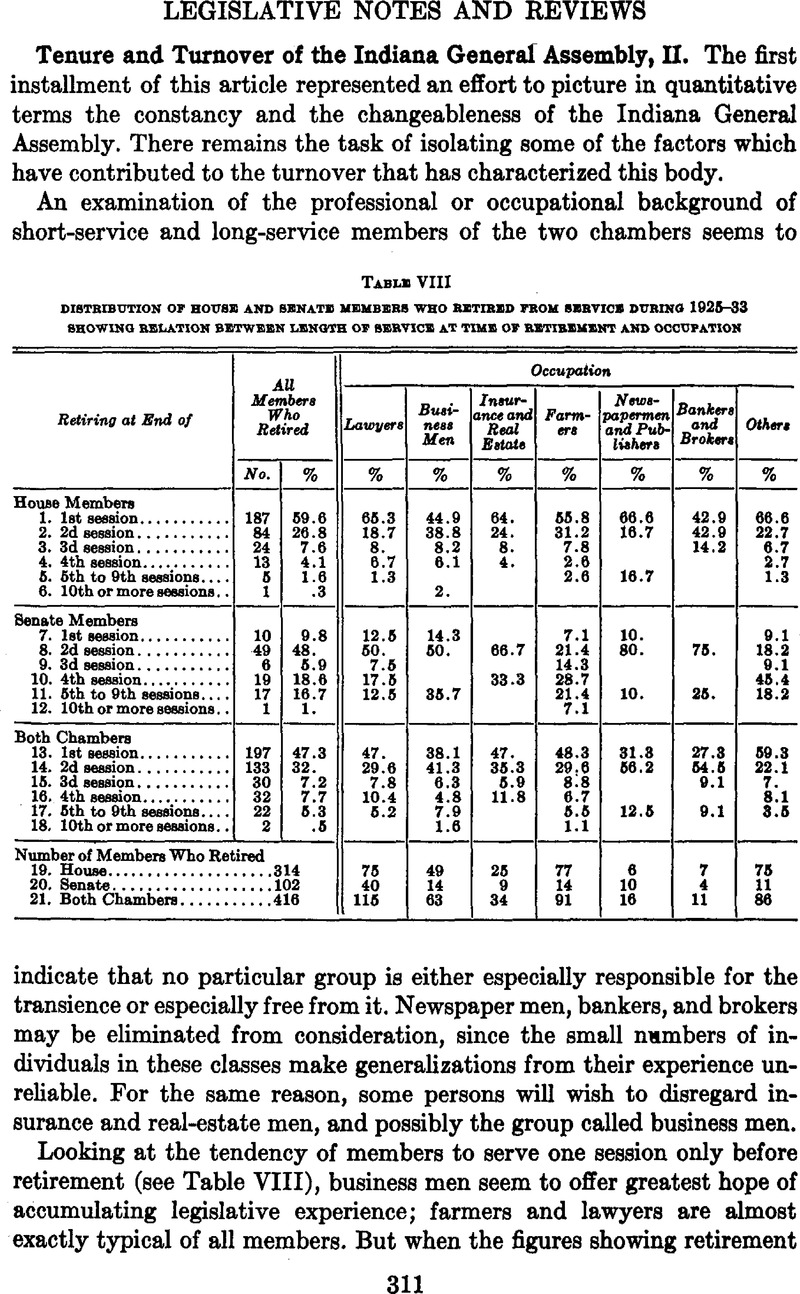

Tenure and Turnover of the Indiana General Assembly, II

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 September 2013

Abstract

- Type

- Legislative Notes and Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Political Science Association 1938

References

21 One might expect greater turnover in the joint district for two reasons: (1) rotating agreements might be more likely to exist where two or more counties compose the district, and (2) joint districts are usually more populous, making campaigning more costly, since ordinarily a part of the joint district is also a separate one-county district. Maps depicting the peculiar Indiana layout of districts can be found in the annual Statistical Report for the State of Indiana. Rotating agreements are discussed below, pp. 322–324.

22 Descriptions of the district types were omitted from Table X because of space limitations. The types are as follows:

Type 1—80 per cent or more of the district population is in incorporated places of 300,000 or more population.

Type 2—50 per cent or more of the district population is in incorporated places of 30,000 to 99,999 population.

Type 3—50 per cent or more of the district population is in incorporated places of 5,000 to 29,999 population.

Type 4—50 per cent or more, but less than 80 per cent, of the district population is in unincorporated places or incorporated places of less than 50,000 population.

Type 5—80 per cent or more of the district population is in unincorporated places or incorporated places of less than 5,000 population.

The apparently peculiar classification of districts is explained by the fact that a classification of 11 types was worked out, but only the ones here indicated are represented in Indiana.

23 These urban members are chosen as follows: 11 representatives are chosen from Marion county at large, and one is chosen from the Marion-Johnson county joint district; five senators are chosen from Marion county at large, and one represents the Marion-Johnson county joint district.

24 The punched cards used in this study indicate for each legislator who has retired whether his departure was due to primary or election defeat. The inconclusiveness of any generalizations which might result from the small number of individuals involved in the present study made it seem fruitless to carry out any analysis of the relation of district types to cause of turnover.

25 The state is divided into 44 senate districts and 75 house districts.

26 Sixty-six of the 92 counties shifted in party control one or more times, as evidenced by the party affiliation of the county auditor, during the period 1916–34. Approximately 82 per cent of the population of the state lives in these 66 counties.

27 It must be remembered that the figures in Tables XIII and XIV, as well as all figures given in this section of the article, are descriptive of retirement from service in the given chamber. The writers have not attempted to learn why a member failed to succeed himself in the legislature, if at some later date he saw further service in the same chamber. Only in case the member did not reappear in that chamber up to and including the 1935 session was any account taken of the cause or avenue of his leaving. This is not true of Table XII, which takes account of all members of the General Assembly.

28 Table XIII correctly shows that 27 senators terminated service in that chamber in 1931. In addition to the 25 whose terms expired, two senators resigned. None has since returned to the senate.

29 The category “Other known causes” in Tables XIII and XIV embraces only members known to have died during the sessions or before the succeeding election, and members who were elected to the other chamber. The writers have not as yet searched the primary and election returns to ascertain which members terminated their service in one house with an unsuccessful candidacy for membership in the other chamber. Nor has any effort been made to ascertain what members sought other offices in the election succeeding their final session. Resignations from either house before expiration of the term have been included under “Unknown causes.”

30 The caution voiced in note 27, supra, p. 317, is applicable in this and the succeeding paragraphs. The figures are for members who terminated their service in the stated chamber.

31 Similar figures for the senate have not been computed. The number of members of either party whose term expires with any given session is so small as to make unconvincing any percentages which might be derived.

32 The writers have considered the desirability of isolating districts which returned a member of the same party to the legislature from those which returned a member of different party than the incumbent. A study of tendency of incumbents to contest in these two sets of districts would offer a refinement of the crude analysis attempted in the foregoing paragraphs. Data making possible such a study are not recorded on the punched cards. The enormous outlay of time and effort which would be required for the inquiry seems not justified by the inconclusive results which would be obtained.

33 At the time of writing, data for the 1936 campaign were not available. The facts and figures on turnover in the house which are offered in this section of the article are based on membership in the assemblies of 1925 to 1933 and the campaigns of the succeeding years. Any seat, therefore, might have changed hands five times.

The caution offered in note 27, supra, p. 317, is not applicable here. In the following discussion, account is taken of members who failed to succeed themselves, even though they subsequently won back their seat. Thus a one-member district that experienced 100 per cent turnover might actually have sent only two different individuals to the house. Cf. the table in note 46, infra, pp. 330–331.

34 The following procedure was used in corresponding with persons in high turnover districts of both house and senate. Personal letters describing the extent of legislative turnover, accompanied by a suggested answer form, were sent to present and former members of the legislature from that district. If the replies showed differences of opinion as to whether rotating agreements existed, or if the number of replies was less than three, further letters were sent to other persons thought likely to be informed, including unsuccessful candidates for the legislature, county party chairmen, and newspaper editors. In the case of the “eleventh” high turnover district just described, nine replies were received, four from former representatives, two from county chairmen, and three from newspaper editors. Seven answers stated in varying degrees of positiveness that no rotating agreements were in operation in either party, one (from a newspaper editor) asserted that rotating agreements were in effect in both parties, while a ninth failed to make a definite reply on this point.

35 Four of these districts consisted of one county each; two were two-county districts; and one was composed of three, counties.

36 In six of the seven districts, all replies clearly indicated, if they did not state categorically, that no agreements existed; in like manner they denied that a popular sentiment in favor of passing the position around had been effective in either party. For one of these six districts, however, only two replies were received. The seventh district produced some difference of opinion, as was indicated supra, note 34.

37 In order to carry the analysis over three elections, the collection of data had to be pushed back to 1923. See supra, p. 315.

38 In one of these 10 districts, all three incumbents obtained renomination; in one district, two obtained renomination.

39 Cf. Tables IX and XI and the accompanying discussion, supra, p. 315. Of the senators representing joint districts, 68.7 per cent terminated their service at the end of one term or less, while 56.6 per cent of those representing one-county districts were equally early quitters. The writers are fully aware that an adequate analysis of rotating agreements would necessitate inquiry into the place of residence and the party and factional affiliations of members of the legislature and of the candidates who opposed them in primary and general election. The writers were concerned here simply to probe the knowledge and opinion of observers in a sampling of districts where it seemed most likely that rotating agreements might be found.

40 In computing these data, account was taken of service in either house, and of service on any committee of either house to which workmen's compensation legislation was referred.

41 Congressional Government (Boston, 1885), p. 295Google Scholar.

42 The 1929 session was chosen because it contained a better representation of experienced senators than any other session. For data, see Table III in this Review, Feb., 1938, p. 60. Facts concerning the number of statutes amended are from table headed “Acts Amended”, in Acts, 1929, p. 849Google Scholar. The list of committees which reported amendatory legislation was prepared from the Senate Journal for 1929.

43 Except for the 1907 law, the distribution of the 22 acts is roughly proportionate to the time of enactment of the 76 amended laws which dated from 1915 to 1927. The 1907 law was included because it was the only amendatory act reported by the committee on finance.

44 These figures are for committee memberships, not for individuals. It must be borne in mind that the foregoing analysis of carry-over of personalities from original enactment to amendment is based on one amendatory law reported by each of 22 committees of the 1929 senate. See supra, p. 326.

45 The 11 replies which failed to mention inadequate pay offered the following causes for failure to seek a second term: one mentioned the demands of his personal business and five listed candidacy for a different office (certainly closely related to the matter of compensation); one moved out of the district; two listed ill health or old age; one bowed before a rotating agreement; and one withdrew on account of his father's candidacy for state office.

46 An act of 1925 provided that the pay of the Indiana General Assembly should be increased from $6 per diem to $10 per diem, effective January 1, 1929, but the appropriation act of 1927 made the $10 per diem available for the 1927 session. An analysis of the tendency of members to seek renomination since the institution of the direct primary (1918 to 1934) yields no conclusive proof that the increase in compensation had any substantial effect on willingness to continue service. The impact of the depression might, of course, have counteracted any effect of the pay increase. The following table shows the percentage of members of each session (whose terms expired) who sought renomination. No effort was made to differentiate occupational groups. Committee chairmen and Indianapolis members were isolated, how ever; neither varied particularly from the figures for all members.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.