Book contents

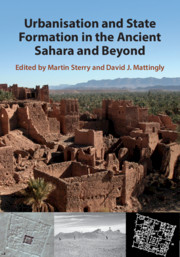

- Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond

- The Trans-saharan Archaeology Series

- Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Oasis Origins in the Sahara: A Region-by-Region Survey

- 2 Garamantian Oasis Settlements in Fazzan

- 3 Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the Eastern Sahara

- 4 The Urbanisation of Egypt’s Western Desert under Roman Rule

- 5 Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the Northern Sahara

- 6 Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the North-Western Sahara

- 7 Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the Southern Sahara

- 8 Discussion

- Part III Neighbours and Comparanda

- Part IV Concluding Discussion

- Index

- References

2 - Garamantian Oasis Settlements in Fazzan

from Part II - Oasis Origins in the Sahara: A Region-by-Region Survey

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 March 2020

- Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond

- The Trans-saharan Archaeology Series

- Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Oasis Origins in the Sahara: A Region-by-Region Survey

- 2 Garamantian Oasis Settlements in Fazzan

- 3 Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the Eastern Sahara

- 4 The Urbanisation of Egypt’s Western Desert under Roman Rule

- 5 Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the Northern Sahara

- 6 Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the North-Western Sahara

- 7 Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the Southern Sahara

- 8 Discussion

- Part III Neighbours and Comparanda

- Part IV Concluding Discussion

- Index

- References

Summary

In this chapter we present a case study of early oasis development relating to the area of south-west Libya known as Fazzan and the ancient people known as the Garamantes. The Garamantes were first firmly identified with this area by Duveyrier in the mid-nineteenth century. As will be explained in more detail below, the archaeological rediscovery of the Garamantes properly commenced with a pioneering Italian mission in 1933. There were some large-scale excavations in the 1960s by Mohammed Ayoub and importantly this included work at the Garamantian capital of Old Jarma (ancient Garama), but the poor quality of the work limited the value of the published outputs. More reliable results were achieved by the team led by Charles Daniels between 1959 and 1977, excavating and surveying a number of sites in the area close to Jarma.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020

References

- 2

- Cited by