Over the past several years, economic inequality has become one of the most discussed topics in social science and social policy. Indeed, no serious discussion of contemporary social and economic life seems complete without a consideration of the growing level of economic inequality that we have seen over the past several decades. In this chapter, I will explore whether, and how, economic inequality – the distribution of income and wealth across social strata – affects the formation and dissolution of families. I write from the perspective of the United States, but I hope my view will be valuable for students of Western Europe and the other overseas English-speaking countries. I will focus on different-sex couples, for whom an historical argument can be assessed. Studies of same-sex couples are underway, and it is not yet clear whether the dynamics are different. I will examine whether economic inequality may be affecting patterns of entry into and exit from cohabitation and marriage, as well as childbearing within or outside marriage. Nevertheless, I will acknowledge that cultural change matters too. Economic conditions are not all powerful. The changes that we have witnessed in family formation would not have happened had the Western world not seen a great shift in attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation over the past half-century.

I have elsewhere referred to these cultural shifts as the deinstitutionalization of marriage (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2004). In retrospect, I think that a more accurate, although less elegant, phrase would have been “the deinstitutionalization of intimate unions.” Marriage itself retains much of its distinctive structure and legal protections, even if it has a less clear set of rules for how spouses are to behave than in the past, but it no longer has a monopoly on intimate unions. A majority of partnerships now begin as cohabiting unions. Cohabiting couples cannot rely on shared understandings and legal statutes to guide their interactions. Rather, they must negotiate how they will act in their relationships. They exhibit a wide variation in commitment. In northern Europe, one commonly finds cohabiting couples who have had long-term stable relationships without ever marrying (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2001), but in the United States, most cohabiting unions lead either to break-ups or to marriage within a few years (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2009). An increasing number of American children are now born into them – one in four at the rates in 2015 (Wu Reference Wu2017). In some cases, the parents may not begin to cohabit until after the woman becomes pregnant (Rackin and Gibson-Davis Reference Rackin and Gibson-Davis2012). Children born to cohabiting couples are exposed to a substantially higher risk of parental union dissolution than are children born to married couples – a relationship common across almost all European countries (DeRose et al. Reference DeRose, Lyons-Amos, Wilcox and Huarcaya2017). Childbearing in cohabiting unions is much more common among Americans without university degrees than among university graduates (Wu Reference Wu2017). A clear social-class line now divides American families at the university-degree level, with graduates much more likely to marry before having a child and less likely to end their marriages. Indeed, it almost seems as though the United States has two family formation systems that are differentiated by the presence or absence of a university degree (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2010).

Economic inequality is relevant for explaining these divergent patterns in partnerships and fertility. A long line of research links marriage formation to labor market opportunities for young men (Becker Reference Becker1991; Oppenheimer Reference Oppenheimer1988; Parsons and Bales Reference Parsons and Bales1955). Men have been, and still are, required to earn a steady income; more recently, it has become desirable, but optional, for women to earn one too – at least among nonpoor couples. Therefore I will focus most of my attention to the changes in the labor market that have affected men. Aggregate-level (e.g., cross-national or cross-state) studies have addressed the consequences of inequality for family-related outcomes, such as the percentages married (Loughran Reference Loughran2002) or divorced (Frank, Levine, and Dijk Reference Frank, Levine and Dijk2014), and for teenage pregnancy and birth rates (Gold et al. Reference Gold, Kawachi, Kennedy, Lynch and Connell2001). My coauthors and I have shown that individuals are more likely to marry before childbearing in places where labor market conditions are better than in places where middle-skilled jobs are scarce (Cherlin, Ribar, and Yasutake Reference Cherlin, Ribar and Yasutake2016). However, statistical studies require specialized knowledge to evaluate, and their mathematical models are almost always subject to limitations. Consequently, nonspecialists often have understandable difficulties evaluating the worth of statistical claims that are made. In this chapter, I would like to present a less technical argument for the proposition that rising income inequality has been an important driver of changes in family. Think of it as a prima facie case – a set of facts that establishes the likelihood that an argument is true, even though it does not prove it. The facts, I hope, will establish the plausibility that income inequality has been an important causal factor. It will also suggest that explanations that reject the importance of income inequality and instead argue that cultural change is the sole driver (e.g., Murray Reference Murray2012) are at best incomplete.

The Dimensions of Income Inequality

Income inequality has several dimensions. Two have received close attention in social commentary. First, much has been written about the growing proportion of income and wealth accruing to people in the highest 1% of the distribution (e.g., Piketty and Saez Reference Piketty and Saez2003). Between the late 1970s and the early 2010s, the amount of income amassed by the top 1% from about 10% to about 20% (Atkinson, Piketty, and Saez Reference Atkinson, Piketty and Saez2011). As dramatic as this rise has been, I would argue that it is not the most important dimension of inequality to think about when studying changes in family structure. Rather, what matters more is a second dimension of inequality: The growing earnings gap between the university-educated (by which I mean individuals with a bachelor’s or university degree or higher) and the nonuniversity-educated. This gap has widened since the 1970s (Autor Reference Autor2014). Prior to that time, manufacturing jobs were more plentiful in the United States. The nation had emerged from World War II as the economic power of the world. In 1948, American factories produced 45% of the world’s industrial output, and the nation’s manufacturing exports accounted for a third of the world total (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). The booming economy and a relative shortage of labor (due to the lower birth rates during the Great Depression) created conditions that were favorable to unionization; and labor unions negotiated for higher wages and better fringe benefits (Levy and Temin Reference Levy, Temin, Brown, Eichengreen and Reich2010).

Yet beginning with the oil embargo by the Arab states in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries in 1973, the long postwar boom subsided. The wages of production workers remained stagnant or declined as manufacturing work moved overseas, where wages were much lower, or was automated, lowering the demand for workers. The proportion of workers who were doing what was commonly called blue-collar work – production workers, craftworkers, fabricators, construction workers, and the like – declined. In contrast, demand for high-skilled professional, managerial, and technical workers remained strong – a development that economists refer to as skill-biased technical change (Autor, Katz, and Kearney Reference Autor, Katz and Kearney2008). It produced a growing earnings gap between middle-skilled workers, who tend to have a secondary-school education, and highly skilled workers, who tended to have a university education. Autor (Reference Autor2014) has estimated that in the period from 1979 to 2012, the rising earnings gap between the typical university-educated household and secondary-school-educated household has cost the latter four times as much in lost income as has the growing concentration of income among the top 1%.

The rising earnings gap has increased inequality by hollowing out the middle of the income distribution, producing what some have called the hourglass economy – a metaphor for the pinched middle (Leonard Reference Leonard2011). Industrial jobs have been the easiest to automate or outsource because they require routine production that can be done by computer or robots or that can be carried out in factories situated far from the place at which the goods they produce will be consumed. In contrast, many low-paying service jobs must be done in person (e.g., waiters, gardeners); and high-paying managerial and technical jobs have remained uncomputerized and performed in the United States. as well. The polarization of low-paying and high-paying jobs, with fewer mid-level jobs in between, creates a higher level of income inequality.

Income Inequality and Family Formation

How then might rising income inequality be associated with changes in family formation? My argument is that the presence of high levels of income inequality is a signal that a weakness exists in the middle of the labor market. That weakness creates the conditions that change family formation. To be sure, income inequality may not inherently be a direct causal force for family change. Perhaps other forms of income inequality in other places at other times might not be as strongly associated with the hollowing out of the middle of the labor market and therefore might have little effect. However, the inequality that we have seen in the United States is connected to the labor market, in that it is harder for a person with a moderate amount of skill – say, a secondary-school diploma and perhaps a few university courses – to get a decent-paying job. In turn, the difficulty of finding middle-skilled jobs depresses rates of marriage and of marital fertility.

The prima facie case for the causal importance of income inequality rests on two basic trends. The first trend is the aforementioned growth since about 1980 of the earnings differential between the university-educated and the less-educated (Autor Reference Autor2014). As I have noted, this gap reflects the relative decline in job opportunities in the middle of the labor market – the kinds of jobs that people without university degrees are qualified for. In addition, among individuals without a university education, the disruption in the middle of the labor market has been sharper for men than for women. Much of the automation and offshoring has occurred among manual occupations that had been seen as men’s work due to their physical, often repetitive, nature at a factory or a construction site. In the American ideal of the working-class family that was socially constructed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, men were supposed to do jobs that required hard physical labor and to bring home a paycheck for the needs of their wives and children. Sociologist Michèle Lamont refers to this conception of the male role as the “disciplined self” (Lamont Reference Lamont2000) and claims that it has been common among White working-class men in the United States. (Lamont found that the self-sufficient breadwinner image was less common among Blacks.) It is this type of manly work that has been subject to shortages and to wage stagnation. Initially, working-class husbands took pride in keeping their wives out of the labor force, but in the postwar period, women moved into paid employment in clerical and service work – the so-called pink-collar jobs that came to be seen as women’s work. Jobs in this sector of the economy have not been hit as hard by the offshoring and automation of production. Consequently, men and women’s earnings have moved in different directions. Between 1979 and 2007, men’s hourly earnings decreased for all those without university degrees. For women, earnings fell only for those without secondary-school diplomas; all others experienced increases. Alone among male workers, the university graduates experienced an increase; and for women, the largest increases were for university graduates (Autor Reference Autor2010).

The second basic trend consists of the divergent paths that family structure has taken during the same period, according to the educational levels of the adults involved. In the 1950s, marriage was ubiquitous. At all educational levels, almost everyone married, and almost all children were born within marriage (Cherlin Reference Cherlin1992). The central position of marriage in family life began to erode in the 1960s and 1970s. Crucially for my argument, the trends in marriage and childbearing were initially moving in the same direction for adults at all educational levels: Marriage was being postponed, cohabitation was increasing, and divorce rates were rising (Cherlin Reference Cherlin1992). However, since about 1980, the family lives of those with a university degree, whom we may call the highly educated, and those with less education have diverged (McLanahan Reference McLanahan2004). Family life among the highly educated remains focused on marriage as the context for raising children, and although the highly-educated marry at later ages, they ultimately have higher lifetime marriage rates than do those with less education (Aughinbaugh, Robles, and Sun Reference Aughinbaugh, Robles and Sun2013). In addition, the divorce rate for highly educated couples has declined sharply since its peak around 1980 (Stevenson and Wolfers Reference Stevenson and Wolfers2007). Meanwhile, the percentage of births outside marriage among the highly educated has remained low. In contrast, the family lives of people with a secondary-school diploma but not a university degree, whom we may call the moderately educated, have moved away from stable marriage. This group has experienced a surge of births within cohabiting unions. Unlike the typical cohabiting unions in some European countries, these unions tend to be brittle and to lead to disruptions at a high rate (Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2015). Among moderately educated married couples (those with secondary-school diplomas), there has not been as much decline in divorce as among the highly educated (S. P. Martin Reference Martin2006). Finally, people without secondary-school degrees, whom we may call the least-educated, have continued to have a high proportion of births outside marriage, although there has been less change in their family patterns since 1980.

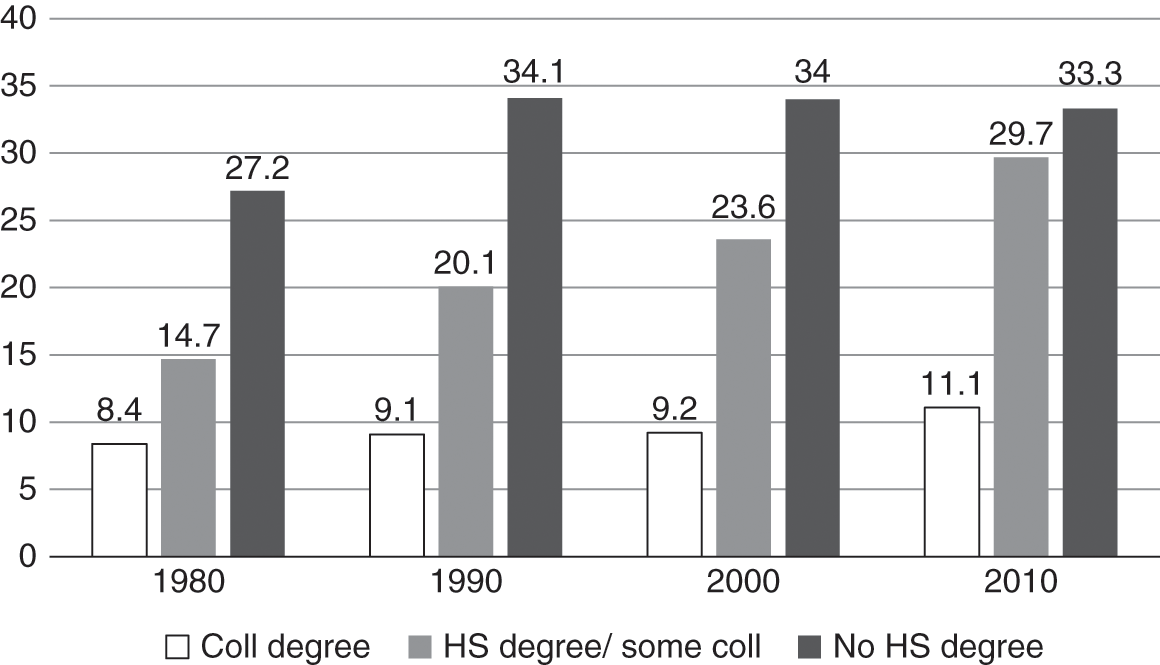

Consequently, the greatest change in children’s living arrangements since 1980 has occurred among the moderately educated, among whom the proportion of children living with single mothers and cohabiting mothers has increased dramatically. Figure 3.1 shows changes in children’s living arrangements for the thirty-year period from 1980 to 2010. Consider the white-colored bars, which show the percentage of children with highly educated mothers who are living in a single-parent or cohabiting-parent family. It hardly changed during the thirty-year period – rising from 8% to 11%. In other words, there was little or no movement away from marriage-based families for the raising of children. Now look at the dark-gray bars, which show children living with least-educated mothers. They were the most likely to live in single-parent or cohabiting-parent families in all years but after increasing from 1980 to 1990, the rate has held steady.

Figure 3.1 Percentage of children living with single and cohabiting mothers, by mother’s education, 1980–2010.

It is the light-gray bars, which show children living with moderately educated mothers, that portray the greatest changes in family structure. Here we see the substantial growth of the proportion of children living in single-parent or cohabiting-parent families – from 15% to 30%. Thus, it is among the moderately educated, that we see both the greatest change toward nonmarital, unstable living arrangements for having and rearing children and the greatest erosion of labor market opportunities – and we see both trends commencing at roughly the same point in time. It is among the highly educated that we see the opposite pairing of trends: Continued high levels of children living in more stable marriages centered on marriage coincided with a rise in the earnings premium for university graduates. This is the prima facie case for the proposition that rising income inequality has been an important indicator of changes in family formation – a marker for the deterioration of the middle of the labor market, especially for men, and an improvement in the labor market for the university-educated. Those who experienced a deteriorating job market trended toward less stable family environments. Those who experienced an improvement in the job market trended toward stable marriage-based family environments.

Many of the highly educated are living an advantaged family life, with two earners providing an ample household income. It is the flipside of the family troubles experienced by the moderately educated. In fact, a number of European and American researchers are claiming that the relatively stable unions of the highly educated are based on a new marital bargain in which the partners share the tasks of paid work, housework, and child-rearing more equally than in the past (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen2009, Reference Esping-Andersen2016; Esping‐Andersen and Billari Reference Esping–Andersen and Billari2015; Goldscheider, Bernhardt, and Lappegård Reference Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård2015). For these observers, the key driver has been the change in women’s roles and the normative shift it has caused. In the mid-twentieth century, marriage and family life was in a stable equilibrium based on a specialization model in which the wife did the housework and child care and the husband did the waged work. When wives began to move into the labor force, they also began to ask their husbands to do more in the home. The result, it is said, was several decades of disruption and dissension as husbands resisted taking on more of what had been seen as wives’ work and as welfare states were slow to support women wage workers through programs such as child-care assistance. However, these scholars argue that a new egalitarian equilibrium is emerging that is based on the sharing of both market and housework by the partners, who may now be either married or cohabiting, and who rely on expanded state support for two-earner families. Social norms, according to this view, have evolved from a breadwinner/homemaker equilibrium in the 1950s to an egalitarian equilibrium that is emerging now.

However, an important limitation of this argument is that the egalitarian bargain rests on the availability of good labor market opportunities for men and generous family-friendly social welfare benefits for couples, such as child-care assistance and family leave. Although the husband is no longer required to be the sole earner of the family, there is still a widespread norm that a man must have the potential to be a steady earner in order to be considered as a good long-term partner (Killewald Reference Killewald2016). Among the moderately educated and least-educated, it is increasingly difficult for men to demonstrate sufficient potential. Consequently, the emergence of a gender-egalitarian equilibrium of committed, domestic work-sharing couples in long-term relationships is likely to be more common in the privileged, university-educated sectors of Western nations than in the less-advantaged, lower educated sectors.

The Influence of Cultural Change

The main counterargument to the prima facie explanation I have presented is that changes in social norms have driven both the decline in earnings among the nonuniversity graduates and the changes in family structure that occurred over the same time span. To be sure, culture is part of the story. During the Great Depression, job opportunities were scarce and yet there was no increase in the percentage of children who were born outside marriage. The reason is that having an “illegitimate” child, as it was called at the time, was socially unacceptable and stigmatizing. Today nonmarital births are much more acceptable than in the past. Without this greater cultural acceptance of alternatives to marriage, we would not have seen the rise in births to cohabiting couples in the United States. Moreover, the weakening of marriage began in the early 1960s, well before the dramatic rise in inequality occurred (Cherlin Reference Cherlin1992).

In fact, marriage is much less central to Americans’ sense of their adult identity today than it was in the past. In the 2002 wave of the General Social Survey – a biennial survey of American adults that is conducted by the research organization NORC at the University of Chicago – respondents were asked which of several milestones a person had to accomplish in order to be an adult. More than nine out of ten selected markers such as being economically independent, having finished one’s education, and not living in one’s parental home, but only about half agreed that one had to be married to be an adult (Furstenberg et al. Reference Furstenberg, Kennedy, McLoyd, Rumbaut and Settersten2004). In the mid-twentieth century, the first step a young person took into adulthood was to get married. The average age at marriage in the 1950s was about 20 for women and 22 for men (US Census Bureau 2016). Only then did you leave home: 90%–95% of all young people married. Today, marriage’s place in the life course, if it occurs at all, is often at the end of the transition to adulthood (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2004). Other paths to adulthood, including having children prior to marrying, cohabiting, and perhaps never marrying, are common and largely acceptable.

A further cultural counterargument is that an erosion of social norms supporting hard work has caused the declining work rates of men, at least in the United States, and by extension, family instability (Eberstadt Reference Eberstadt2016; Murray Reference Murray2012). Although we have seen changes in men’s and women’s work and family roles, one norm has held constant: Men must be able to provide a steady income in order to be considered good candidates for marriage. Killewald (Reference Killewald2016) found that men who are not employed full-time have an elevated risk of divorce, but that low earnings were not necessarily a risk factor as long as the men worked steadily. Other studies suggest that while a woman might choose to cohabit with a man whose income potential is in doubt, she is unlikely to marry him – and he may agree that he is not ready. In focus groups conducted with cohabiting young adults in Ohio, several couples told the researchers that everything was in place for a wedding except for the finances, and that until they were confident of their finances, they would not marry (Smock, Manning, and Porter Reference Smock, Manning and Porter2005).

It is alarming to some observers, then, that the percentage of prime-age men who are working or looking for work has declined, particularly among men without university degrees. Eberstadt (Reference Eberstadt2016) reported that the percentage of 25–54-year-old men who were employed dropped from 94% in 1948 to 84% in 2015. He cites a number of factors, including the employment problems faced by the growing number of men who have returned to the general population after serving prison sentences, but he suggests that a decreasing motivation to work among certain groups of men may be part of the story. In contrast, university-educated men are working almost as hard as in the past (Jacobs and Gerson 2005). One might think, then, that university graduates prefer to work longer hours more than do less educated men.; however, that is not true.

In fact, the General Social Survey shows that there has been a decline in the desire to work long hours among both secondary-school-educated men and university-educated men. In several of the survey’s biennial waves, respondents were handed a card showing five characteristics of a job and asked to rank them in importance. One characteristic was “Working hours are short, lots of free time.” In the 1973–1984 period, the proportion of men aged 25–44 who rated it as most or second-most important was 13%; in the combined 2006 and 2012 samples, it rose to 28% (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). It seems, then, the percentage of men who highly valued short working hours and lots of free time has increased. However, the increase was just as sharp for university graduates as it was for those with a secondary-school diploma but not a university degree. (There was no increase among men without secondary-school diplomas.) So both moderately educated and highly educated men seem to value working short hours more than they used to. Yet only the moderately educated men are actually working less than they used to. On the contrary, Americans working in the professional, technical, and managerial sectors of the labor force tend to work longer hours than their European counterparts (Jacobs and Gerson 2005). The survey results therefore raise this question: If both highly educated men and moderately educated men had a growing preference for shorter hours and more free time, why was only the latter group actually working shorter hours than in the past?

The answer, I would argue, is that employment opportunities and earnings levels for the university-educated men were improving so much that some of these men decided to work longer hours than they preferred: The attraction of the jobs that were available to them – notably higher wages and salaries – more than balanced their attraction to free time. Among moderately educated men in contrast, employment opportunities were not attractive enough to override their growing preference for free time. In other words, whether a man is working depends on both his preferences for work and the opportunities available to him. The decline in men’s labor force participation is rooted in a cultural shift as well as a change in the labor market. Both cultural and labor market factors are necessary to explain the decline.

More generally, this example suggests how intertwined economics and culture are in producing the trends we have seen in family life. Economic sociologists have long argued that economic action is embedded in social institutions (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1985): People make decisions about employment in a cultural milieu. Currently, that milieu may be more favorable toward other activities and leisure than in the past. Some observers might judge that milieu negatively and decry the choices working-age men may make, but cultural forces can be overridden by the opportunity for higher paying, stable work or they can be reinforced through job opportunities that are insecure and lower paying. Cultural forces do not alone determine how young adults will relate to family and work, and nor, it must be said, do economic forces.

One other cultural phenomenon may be contributing to the class differences, not by its transformation but by its stubborn persistence: Ideas about masculinity (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). As I noted earlier, working-class men have taken pride in hard physical labor. Meanwhile jobs that involved caring for and serving others came to be associated with women. These caring-work jobs typically pay less than industrial jobs, which may explain some of the reluctance of men to take them, but they also seem to be devalued in status, at least among men, precisely because they are seen as unmanly jobs (England Reference England2005). As a 53-year-old man who had lost several jobs to automation and to factories that moved to other cities, told a reporter for the New York Times, he never considered work in the health sector of the labor market: “I ain’t gonna be a nurse; I don’t have the tolerance for people,” he said. “I don’t want it to sound bad, but I’ve always seen a woman in the position of a nurse or some kind of health care worker. I see it as more of a woman’s touch” (Miller Reference Miller2017). What we might call conventional masculinity – and what the literature sometimes calls “hegemonic masculinity” (Connell Reference Connell1995) – still prescribes that some jobs are men’s jobs and others are for women. The problem is that men’s jobs have been disproportionately affected by the globalization and automation of production. In the meantime, service jobs have opened up, as in the health sector, but men have resisted taking them. Working-class men’s resistance to doing jobs that are not considered manly enough contributes to the difficulties they face in the labor market.

Discussion

The social-class differences in family formation that are apparent today are not unprecedented. Rather, we are seeing, in a sense, a return to the historical complexity of family life (Therborn Reference Therborn2004). That complexity was apparent throughout the early decades of industrialization during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when there was a great growth of factory jobs. During this period, traditional-skilled jobs in the middle of the labor market, such as those performed by independent craftsmen, yeomen, and apprentices in small shops, were undercut by factory production. Independent shops either collapsed or turn into larger factories. Inequality increased, and as is the case today, the middle of the labor market was hollowed out. Sharp social-class differences in marriage rates were visible; professional, technical, and managerial workers were more likely to marry than were workers with less remunerative jobs (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014). The prosperous period of stability just after World War II, when almost everyone married, fertility rates were high, and divorce rates were unusually stable (Cherlin Reference Cherlin1992), was the most unusual time in family life since industrialization and should not be taken as an anchor point.

Nevertheless, the complexity of family life we see today is different from the complexity of the past. The high rates of cohabitation and of childbearing outside marriage that are now prevalent were rare during the disruptions of early industrialization. Nor, as I noted, were they present during the disruption of the Great Depression. The culture of family life was different; alternatives to marriage such as cohabitation and single-parent families (other than those due to widowhood) were unacceptable to most people. So if a young adult was not married, he or she probably lived in the parental home or boarded in another family’s home and remained childless. The growth in the number of people who were living alone is largely a post-World War II phenomenon, as the housing stock increased and wages and salaries (and therefore the ability to pay rent) rose (Kobrin Reference Kobrin1976; Ruggles Reference Ruggles1988). The lives that unmarried young adults in the United States led in the past are more similar to family life today in countries such as Italy, where it is common for twenties to live at home, remain childless, and marry in their late twenties and early thirties.

One must also include the growth of a more individualistic, self-development oriented culture in the story of changes in family formation today. This cultural development may be connected to a larger shift among the population of the wealthy countries to what are called post-materialist values (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1997). As societies have become wealthier and have solved the problem of providing basic needs, it is said individuals have come to value self-expression – the development of one’s personality – over survivalist values such as providing food, shelter, and basic financial support. One aspect of self-expression is the examination of whether one’s intimate partnership continues to meet one’s needs. If not, the self-expressive individual will consider ending that partnership and finding a new one that better fits her or his continually developing self. Thus, self-expression is associated with higher rates of union dissolution and re-formation. Post-materialist values also include a decline in traditional religious beliefs; in the West that decline is consistent with a rise in nonmarital partnerships and childbearing outside marriage. Overall, a rise in post-materialist values is consistent with what demographers have called the second demographic transition (van de Kaa Reference Van de Kaa1987; Lesthaeghe and Surkyn Reference Lesthaeghe and Surkyn1988): The period since the 1970s during which cohabitation, nonmarital births, and low fertility have become common in most Western countries. Moreover, during this period, there has been a decline in civic engagement – social ties, attendance at religious services, and participation in local associations – that has been more pronounced among those without university educations (Putnam Reference Putnam2015).

Note, however, that second demographic transition theory does not explain the continued strength of marriage and the decline in divorce rates that have occurred among highly educated Americans in this period. It provides no explanation for a seeming transition back toward a family form characterized by relatively stable marriage, albeit preceded by cohabitation. Highly educated young adults were previously thought to constitute the nontraditional vanguard, providing new models of family life that diffused down the educational ladder. That is not, however, what we have seen; rather, the patterns in the United States suggest a neo-traditional highly educated class and a growth of nontraditional behavior among those with less education. At least in the United States, then, second demographic transition theory cannot provide us with an explanation for the growing divide in family life.

That divide suggests a role for the momentous changes in the economy that have differentially affected the highly educated and the less educated. Nevertheless, one must be careful in attributing social change solely to economic inequality. It has become the go-to explanation for a wide variety of social phenomena. One frequently cited book claims that inequality has caused anxiety and chronic stress that has led to a long list of consequences that include poorer physical health, higher mortality, greater obesity, lower educational attainment, higher teenage birth rates, greater exposure among children to conflict, higher rates of imprisonment, more drug use, less social trust, and less social mobility (Wilkinson and Pickett Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2009). All of this is deduced solely from macro-level correlations at the national or state level. It seems unlikely that any social phenomenon could have effects this broad, and in any case, macro-level correlations do not prove the case. The claims in the literature (as well as in this chapter) must therefore be carefully scrutinized and subject to further research.

This chapter also presents a very US-centric perspective that may be less applicable in Europe. The American social welfare system is well known to be among the least generous in the Western world – it is the archetype of the “liberal” (free-market oriented) welfare state in the classic formulation of Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) – and compared to other nations, it provides a larger proportion of its benefits through programs that are contingent on work effort (Garfinkel, Rainwater, and Smeeding Reference Garfinkel, Rainwater and Smeeding2010). Therefore, it does less to support low-income families that do not have steady wage earners than do the welfare systems in other countries. It also provides less support for working parents, in terms of paid family leave or child-care assistance. This lack of support may be one reason why rates of union instability and childbearing among single parents are high in the United States from an international perspective (see Chapter 1). Moreover, the idea that a couple should not marry until they are confident that they will have an adequate steady income (Gibson-Davis, Edin, and McLanahan Reference Gibson-Davis, Edin and McLanahan2005) seems to be stronger in the United States than elsewhere. Perelli-Harris (Reference Perelli-Harris2014) and her colleagues convened focus groups in nine settings in Europe to discuss cohabitation and marriage. They found that the rise of education has not devalued the cultural meaning of marriage; however, they did not hear much discussion of economic uncertainty and its relationship to whether a cohabiting couple should marry.

Nevertheless, the prima facie case that inequality – and more specifically the diverging labor market opportunities for the highly educated and the moderately educated – has driven family formation and dissolution seems strong for the United States. It is not the complete explanation for the great changes in these behaviors that have occurred in the past half-century or so, but it does not need to be. To be sure, had bearing children outside marriage not become acceptable, had cohabitation not become the predominant way that young adults enter into a first union, had survival values persisted over self-expressive values, we would not have seen the same retreat from marriage and marital childbearing; however, had employment opportunities for secondary-school-educated men not deteriorated and had corporations not been able to use the mobility of capital to undermine unionized factories, we would probably not have seen the same retreat either. Culture alone cannot explain the increasingly divergent paths by which the university-educated and the nonuniversity-educated are forming and maintaining families. It seems highly likely that one must take into account the economic changes that have occurred in the increasingly unequal American society.

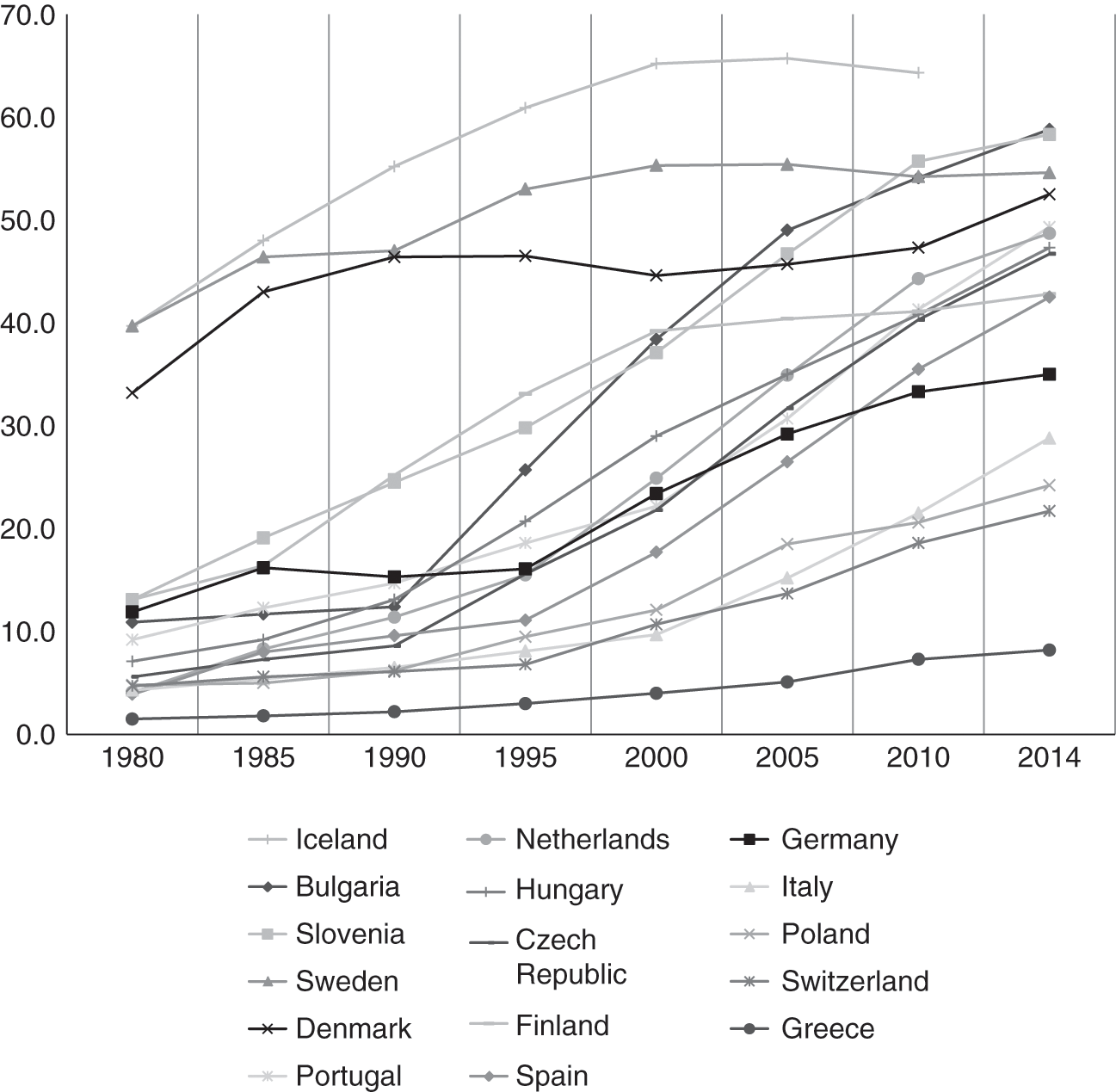

New family formation behaviors have increased nearly everywhere in Europe. Cohabitation, childbearing within cohabitation, divorce, separation, and repartnering have all become more common, even in places where scholars did not think that these behaviors would emerge (see Chapter 1). Recent data from the OECD (2016a) shows that nonmarital fertility, for example, increased dramatically in nearly every country in Europe throughout the 2000s, even across much of southern and Eastern Europe (Figure 4.1). However, European countries still vary widely with respect to the prevalence of new family formation behaviors. For example, in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, the majority of births occur within cohabitation, while in other countries, such as Italy and Romania, childbearing within cohabitation is still relatively rare (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Sigle-Rushton2012). Figure 4.1 shows that although nearly every country in Europe experienced increases in nonmarital fertility, the year in which the increases began differs across countries, as does the speed of the increase.

Figure 4.1 Percentage of nonmarital births in selected countries, 1980–2014

The nearly universal increase in new family formation behaviors coupled with the diversity in the timing and rate of increase raises questions about whether the underlying causes are universal, or if the process of development is unique in each context. Several scholars have proposed overarching theories to explain the observed changes, the most well-known of which is the second demographic transition (SDT) (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe2010; Van de Kaa Reference Van de Kaa1987). Proponents of SDT theory posit that shifting values, ideational change, and increasing individualization have led individuals to choose unconventional lifestyles and living arrangements, often defying the traditional marital pathway of their parents (Lesthaeghe Reference Lesthaeghe2010). SDT theory also implies that those with higher education were the forerunners of the change, as they challenged patriarchal institutions and focused on the pursuit of self-actualization (Lesthaeghe and Surkyn Reference Lesthaeghe and Surkyn2002).

There is scant evidence, however, that the emergence of new behaviors is due to the pursuit of self-actualization or practiced by the more highly educated. Indeed, recent evidence (as discussed in Chapter 1) indicates that childbearing within cohabitation is associated with lower education (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010), divorce has increasingly become associated with lower education (Matysiak et al. Reference Matysiak, Styrc and Vignoli2014), and the highly educated are more likely to marry (Isen and Stevenson Reference Isen and Stevenson2010; Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2013). These studies suggest that new forms of family behaviors are associated with a “pattern of disadvantage.” Although social norms have shifted to become more tolerant of cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing, the less-educated face greater uncertainty and economic constraints, which is reflected in their relationship choices (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010).

Nonetheless, despite evidence that many aspects of the family are changing across Europe, and some of these new aspects are associated with lower education, a consistent association between family change and social class has not been observed for all behaviors or in all contexts (Mikolai, Perelli-Harris, and Berrington Reference Mikolai, Perelli-Harris and Berrington2014; Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Sigle-Rushton2012). Superficial trends may be masking substantial underlying differences in specific processes and consequences. In fact, research has found that although many aspects of family formation are changing, they might not be converging in the same way or toward a similar standard (Billari and Liefbroer Reference Billari and Liefbroer2010; Sobotka and Toulemon Reference Sobotka and Toulemon2008). Several studies have found that while transitions to adulthood are becoming more complex, heterogeneous, and “destandardized” throughout Europe, trajectories do not appear to be converging on one particular pattern or type of new trajectory (Elzinga and Liefbroer Reference Elzinga and Liefbroer2007; Fokkema and Liefbroer Reference Fokkema and Liefbroer2008; Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2015). In addition, while some elements of partnership formation, such as the postponement of marriage, seem to be universally associated with higher education, country context appears to be much more important for predicting partnership trajectories than individual-level educational attainment (Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2016). Thus, while some aspects of family formation, such as the postponement of marriage and fertility, seem to be changing on a wide scale, others, such as long-term cohabitation and union dissolution, seem to be dependent on the social, economic, political, religious, and historical contexts that shape family behavior.

In this chapter, I will explore the diversity and similarity of partnership experiences throughout Europe, drawing on recent research and evidence. I will focus on the emergence of cohabitation as a new family form, especially as a context for childbearing. Cohabiting unions are heterogeneous living arrangements, with some couples sliding into temporary partnerships of short duration, others testing their relationship to see if it is suitable for marriage, and still others living in long-term committed unions with no intentions of marriage (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Mynarska and Berghammer2014). Yet, on average, cohabiting unions are more likely to dissolve, even if they involve children (Galezewska Reference Galezewska2016; Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2015). Also, as discussed above and in Chapter 1, childbearing within cohabitation is often associated with low education, resulting from a pattern of disadvantage (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010). Thus, the costs of union dissolution more commonly fall on already disadvantaged individuals, potentially exacerbating inequality.

This chapter will cover findings from a mixed methods project that examined cohabitation and nonmarital childbearing across Europe and the United States from different analytical perspectives.Footnote 1 First, I will describe the spatial variation in nonmarital fertility across Europe to illustrate how patterns of family change may be influenced by political or cultural borders as well as the persistence of the past. Second, I will outline the laws and policies governing cohabitation in nine European countries to demonstrate how welfare states may be ill-equipped to deal with the new realities of more people living outside marriage. Third, I will draw on a large focus group project to describe discourses surrounding cohabitation and marriage in eight European countries to better understand similarities and differences in cultural and social norms. Finally, I will address the potential consequences of new partnership behaviors by summarizing a recent project that examines the health and well-being of cohabiting and married people. This section will discuss whether marriage, versus remaining in cohabitation, provides benefits to adult well-being beyond simply living with a partner. Throughout, I will speculate about why partnership behaviors differ across countries. Taken together, these studies portray a complex picture of family change in Europe today and raise questions about whether the interrelationship between family trajectories and inequality may be mediated by country context.

The Diffusion of New Family Behaviors: Universal Change – Uneven Distribution

One of the best ways to illustrate the diversity of family formation behaviors is with a map (Figure 4.2, Klüsener, Perelli-Harris, and Sánchez Gassen Reference Klüsener, Perelli-Harris and Gassen2013). The variegated landscape of nonmarital fertility can reveal clues into the fundamental reasons why marriage has declined in some countries, while remaining the predominant context for childbearing in others. Figure 4.1 shows the percentage of nonmarital births across Europe in 2007, with the lightest regions indicating that less than 10% of births occur outside marriage and the darkest regions indicating that up to 75% of births occur outside marriage. Note that the diffusion of nonmarital fertility has primarily been driven by the increase in childbearing within cohabiting partnerships, not births outside a union (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Sigle-Rushton2012). Thus this map portrays a rapid increase in a new and emerging behavior. More recent nonmarital childbearing statistics on the national level (OECD 2016a) suggest that the entire map has become even darker over the past seven years as the percentage of births outside marriage has reached unprecedented highs; however, these statistics are not available on the regional level. The map shown here is important for showing gradations of patterns on the regional level, thus providing insights into the link between spatial variation and the persistence of the past (Klüsener Reference Klüsener2015).

Figure 4.2 Percentage of births outside marriage, 2007

First, notice that the patchwork of high and low regions does not necessarily accord with particular welfare regimes, or even typical geographic areas. Nonmarital fertility is very high in the Nordic countries, with the highest levels in northern Sweden and Iceland, reflecting a long history of female independence and permissiveness of alternative living arrangements (Trost Reference Trost1978). Nonmarital fertility is also high in France, where cohabitation rose rapidly during the 1980s, possibly due to policies which favored single mothers or as a rejection of the Catholic Church and the institution of marriage (Knijn, Martin, and Millar Reference Knijn, Martin and Millar2007). Eastern Germany also stands out as a region with particularly high levels of nonmarital fertility, dating back to the Prussian era (Klüsener and Goldstein Reference Klüsener and Goldstein2014) and increasing during the socialist period through policies favoring single mothers (Klarner Reference Klärner2015), and after the collapse of socialism, by high male unemployment and female labor force participation (Konietzka and Kreyenfeld Reference Konietzka and Kreyenfeld2002). Of the Baltics, Estonia has the highest level of nonmarital fertility, reflecting greater secularization than in Latvia and Lithuania, which have maintained Catholic or traditional social norms favoring marriage (Katus et al. Reference Katus, Põldma, Puur and Sakkeus2008). Bulgaria is another, southern European, country with unexpectedly high levels of nonmarital fertility, possibly due to cultural practices in rural areas or as a response to economic insecurity (Kostova Reference Kostova2007). Other regions also have surprisingly high nonmarital fertility, for example, parts of Austria and southern Portugal, which harken back to norms only permitting marriage upon inheritance of the family farm.

Very low levels of nonmarital fertility are primarily concentrated in southern Europe, for example, in Greece, Albania, and southern Italy. Studies have indicated that Italy has had a “delayed diffusion” of cohabitation, potentially because parents have opposed their children living together without being married (DiGiulio and Rosina Reference Di Giulio and Rosina2007; Vignoli and Salvini Reference Vignoli and Salvini2014). The vast majority of births also continue to occur within marriage in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia, reflecting traditional religious and cultural practices (Klüsener Reference Klüsener2015). In addition, a large swathe of Eastern Europe has very low levels of nonmarital fertility, including parts of eastern Poland, Western Ukraine, and Belarus. Thus, this map and more recent data (OECD 2016a) indicate that some areas appear to be resistant to the changes sweeping across Europe, although some of the very low levels may be due to underreporting (Klüsener Reference Klüsener2015).

When we look closer at the map, we can further see that both political and cultural borders can be very important for delineating the patterns of nonmarital fertility (Klüsener Reference Klüsener2015). In some instances, distinct state borders imply that national policies and legislation can have a strong effect on decisions to marry. For example, the Swiss–French border denotes a sharp distinction between high levels of nonmarital fertility in France and low levels in neighboring Switzerland, despite sharing a similar language and employees who commute daily. The strong distinction in nonmarital fertility is most likely due to strict Swiss policies for unmarried fathers, who were not allowed to pass down their surname if they were not married to the mother of their child. Note, however, that these policies were recently relaxed, and 2014 estimates indicate rapid change with one fifth of all Swiss births outside marriage (OECD 2016a).

In some regions, however, state borders do not define patterns of nonmarital fertility, suggesting that cultural or religious influences are more important. For example, the percentage of nonmarital births is very low across the borders of eastern Poland and Western Ukraine, despite different family policy regimes (Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris Reference Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris2015), indicating that the long history of Catholicism in this area has maintained strong social norms toward marriage. Furthermore, some countries have strong differences within their borders, for example nonmarital childbearing varies considerably from the north of Italy to the tip of the boot. In sum, it is fascinating to stare at the map and recognize that both political and cultural factors may influence such a fundamental demographic phenomenon as the partnership status at birth. Below I investigate these factors in more detail.

Policies and Laws: Universal Rights – Unequal Treatment

Along with complex social and cultural factors, the countries of Europe are defined by a complicated array of policies, laws, and welfare institutions, all of which shape the family and the relationship between couples (Neyer and Andersson Reference Neyer and Andersson2008). Family demographers have long examined how welfare state typologies (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990) and constellations of family policies influence fertility (e.g., Billingsley and Ferrarini Reference Billingsley and Ferrarini2014; Gauthier Reference Gauthier2007; Thévenon Reference Thévenon2011) and lone parenthood (Brady and Burroway Reference Brady and Burroway2012; Lewis Reference Lewis1997). Here, I will discuss the laws and policies that govern marital and cohabiting relationships. This perspective will provide insights into how legal rights and responsibilities are similar or different across countries, sometimes as a result of underlying economic and welfare state models. It is important to keep in mind that laws and regulations often provide couples with a sense of security and stability, which may influence decisions around partnership formation and marriage. In addition, depending on how they are enacted and enforced, laws and policies may also potentially exacerbate disadvantage and inequality.

Up to the 1970s, marriage was the primary way of organizing family life. European states regulated couples and families primarily through the institution of marriage by providing rights such as joint taxation, widow’s pensions, and inheritance only to married couples (Coontz Reference Coontz2005). In addition, states regulated the relationship between parents and their children, for example, children’s rights to maintenance and inheritance and parents’ rights to child custody and recognition. Until the mid-twentieth century, marriage was the only living arrangement in which childbearing was legitimate, but gradually discrimination against children born outside marriage was abolished and single mothers were granted custody. By the mid-1970s, most European states had also developed legal mechanisms for dissolving a marriage that would regulate the division of assets and financial savings and provide alimony to the weaker party in case of divorce (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Berrington, Gassen, Galezewska and Holland2017a).

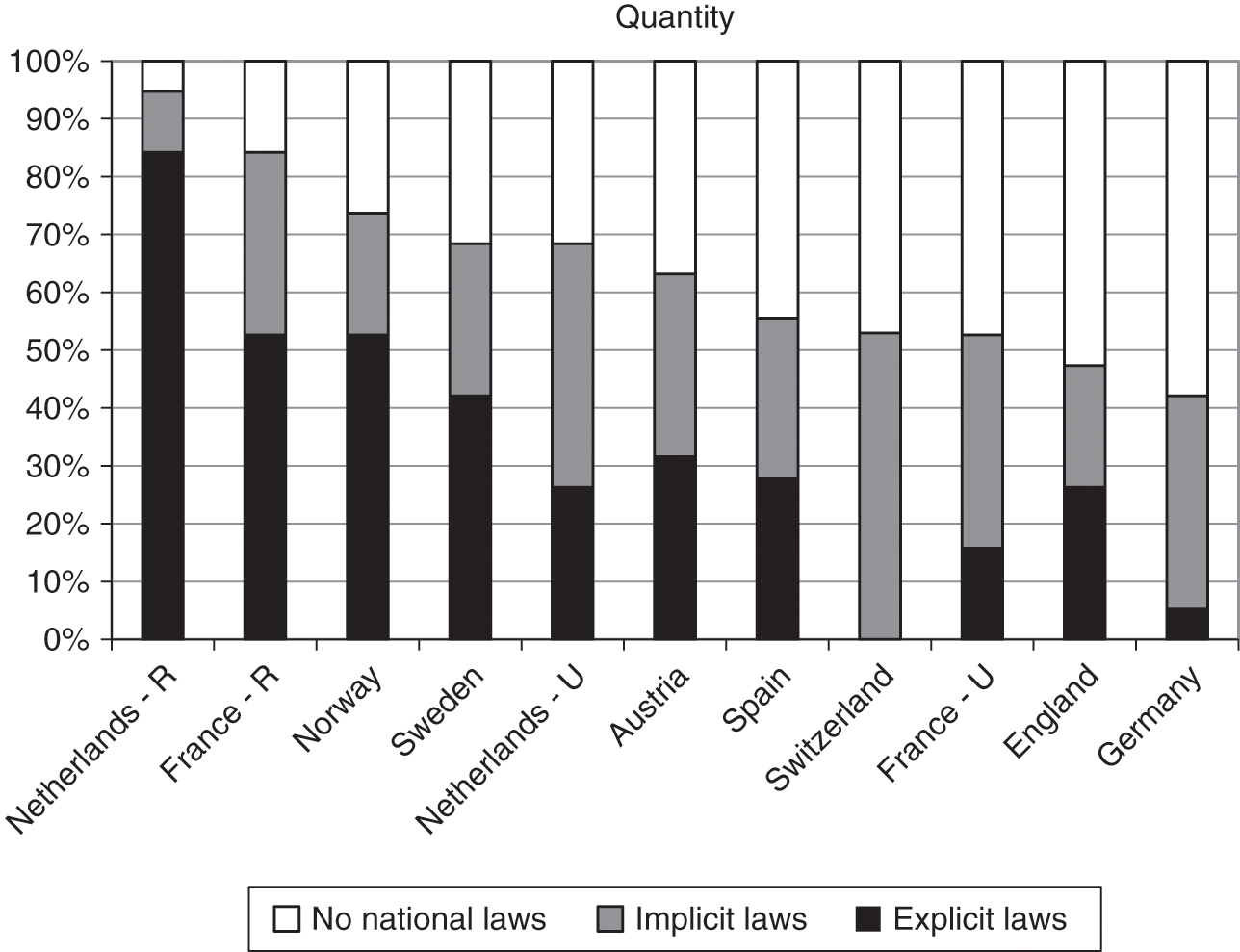

Over the past few decades, many states have started to extend the rights and responsibilities of marriage to couples living in nonmarital relationships (Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen Reference Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen2012). The extent of the legal recognition of cohabitation depends on historical developments, resulting in great variation in the degree of harmonization between cohabitation and marriage across the continent (see Figure 4.3). Generally, countries have taken one of several approaches to recognizing and regulating cohabitation (Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris Reference Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris2015). Some countries, for example, Sweden and Norway, have extended many marital rights and responsibilities to cohabiting couples, especially if they meet certain conditions such as living together for a defined period (e.g., two years) or having children together. Countries such as the Netherlands and France have implemented an opt-in approach, which entitles registered partners (in the Netherlands) or PACS (civil solidarity pacts; in France) to additional rights, such as joint income tax and inheritance, but made it easier for them to separate than divorce. Still other countries, such as England and Spain, have taken a piecemeal approach, with rights extended in some policy domains but not others. As Figure 4.3 shows, these different approaches have resulted in countries falling along a continuum in the degree to which they have harmonized cohabitation and marriage policies, with countries that have adopted registered partnerships and marriage-like arrangements at one end, and countries which favor marriage, such as Switzerland and Germany, at the other (Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen Reference Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen2012).

Figure 4.3 Percentage of policy areas (out of 19) that have addressed cohabitation and harmonized them with marriage in selected European countries

Note: R = registered cohabitation or Pacs; U = unregistered cohabitation.

One policy area that has changed in all countries has been the expansion of the rights of unmarried fathers. Unmarried fathers have the right to establish paternity and attain joint – or sole – custody over their children; however, in all countries they must take additional bureaucratic steps to establish paternity and/or apply for joint custody. Another area which is similar across most countries is the restriction of welfare benefits for cohabiting partners. Generally, unemployment benefits are means-tested and based on households, taking into account the income of all household members (including cohabiting partners). Other policy areas depend on the fundamental relationship between the state, the individual, and the family. Tax systems in Sweden and Norway, for example, are organized around the individual rather than the couple, resulting in similar tax rules for cohabiting and married individuals. Germany and Switzerland, on the other hand, which continue to favor the male breadwinner model, only allow married couples to benefit from tax breaks if one partner earns more than the other.

One of the areas which can have the greatest consequences for the reproduction of inequality is whether cohabitants who separate are protected by the law or have access to family courts. As many studies have shown, cohabiting couples have higher dissolution risks, even when the couple has children together (Galezewska Reference Galezewska2016; Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2016). Often these couples have lower education and income, putting them at greater risk of falling into poverty (Carlson (this volume); Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010). The lack of legal protection for cohabiting couples can be especially pertinent if one partner (usually the woman) is financially dependent, due to household maintenance and child care, or gender wage differentials. In some countries, such as the UK, the lack of legal regulation may restrict the vulnerable partner’s access to state resources that help to solve property disputes or apply for alimony (The Law Commission 2007). Even though the state may require unmarried fathers to pay child maintenance, the regulations may not be sufficient if the mother does not have access to the courts or the resources to hire a lawyer. In addition, cohabiting partners without children have no legal claim to resources, even if they contributed to the relationship, which could result in a substantial decline in living standards for the vulnerable partner (Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris Reference Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris2015).

Again, protections upon separation depend on whether the state has implemented registered partnerships and the degree to which the state organizes benefits around individuals or families. Registered partners in the Netherlands have many of the same rights as married partners in respect of the division of household goods, the joint home, other assets, and alimony. PACS in France have fewer regulations governing the division of household goods and assets, and no provision for alimony. Sweden and Norway regulate the division of household goods and assets for cohabiting couples, but the tax and transfer system is based on the individual. Most other European countries provide no legal guidance during separation for cohabitants, with the exception of provisos for those separating with children; for example, Germany and Switzerland require separated fathers to pay maintenance to their partners while their children are very young. Overall, this lack of regulation can make it very difficult for vulnerable cohabiting individuals to apply for maintenance or support, and as a result income may fall more after cohabitation dissolution than after divorce.

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that many individuals cohabit precisely because they want to avoid the legal jurisdiction of marriage. They may want to keep their finances and property separate, maintain their independence, and avoid bureaucratic entanglements. Previously married cohabitants may decide to remain outside the law to avoid a costly or time-consuming divorce or protect assets for their children. Given the variety of reasons for cohabiting, it is difficult to know to what extent laws should regulate cohabiting relationships, especially if people are likely to slide into relationships without knowing their responsibilities (Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen Reference Perelli-Harris and Sánchez Gassen2012). In any case, it is important to keep in mind how legal and welfare systems may exacerbate the risk of disadvantage. The legal policies governing cohabitation, marriage, and separation across Europe may have implications for whether states protect vulnerable individuals from slipping further into poverty.

Culture and Religion: Universal Themes – Unique Discourses

As described above, the historical, cultural, and social context is fundamental for shaping attitudes and social norms toward family formation. Social norms are reflected in how people talk about families, and what they say about cohabitation and marriage. They also provide insights into how countries are similar or different from each other. This section draws on a cross-national collaborative project, which used focus group research to compare discourses on cohabitation and marriage in nine European countries (see Perelli-Harris and Bernardi Reference Perelli-Harris and Bernardi2015). Focus group research is not intended to produce representative data, but aims to provide substantive insights into general concepts and a better understanding of how societies view cohabitation. Collaborators conducted 7–8 focus groups in the following cities: Vienna, Austria (Berghammer, Fliegenschnee, and Schmidt Reference Berghammer, Fliegenschnee and Schmidt2014), Florence, Italy (Vignoli and Salvini Reference Vignoli and Salvini2014), Rotterdam, the Netherlands (Hiekel and Keizer Reference Hiekel and Keizer2015), Oslo, Norway (Lappegård and Noack Reference Lappegård and Noack2015), Warsaw, Poland (Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj, and Matysiak Reference Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj and Matysiak2014), Moscow, Russia (Isupova Reference Isupova2015), Southampton, United Kingdom (Berrington, Perelli-Harris, and Trevena Reference Berrington, Perelli-Harris and Trevena2015), and Rostock and Lubeck, Germany (Klärner Reference Klärner2015). Each focus group included 8–10 participants, with a total of 588 participants across Europe. The collaborators synthesized the results in an overview paper (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Mynarska and Berghammer2014) and each team wrote country-specific papers, which were published in 2015 as Special Collection 17 of Demographic Research (entitled Focus on Partnerships). The results of this project are the basis for the discussion below.

The most striking finding from the focus group project was how the discourses in each country described a vivid picture of partnership formation unique to that context. In the countries with the lowest levels of cohabitation, Italy and Poland, focus group participants responded that cohabitation provides a way for couples to test their relationship, but in Poland participants tended to emphasize the unstable nature of cohabitation. In both countries, participants discussed the role of the Catholic Church, but in Italy the emphasis was more toward the tradition of marriage and family, while in Poland it was on religiosity and the heritage of the Church. In Western Germany and Austria, participants took a life-course approach to cohabitation and marriage: Cohabitation is for young adults, who are oriented toward self-fulfillment and freedom, while marriage is for later in the life course, when couples should settle down and be more responsible. Thus, marriage signifies stability, protection, and safety, especially for wives and children.

The discourses in the other countries were also unique. In the Netherlands, a recurring theme was that cohabitation was a response to the increase in divorce. Cohabitation was a way of dealing with possible relationship uncertainty, and marriage was the “complete package,” although registered partnerships or cohabitation contracts could also provide legal security. In the United Kingdom, participants expressed tolerance for alternative living arrangements, but unlike in the other countries, differences between higher and lower educated participants were more apparent. The higher educated tended to think marriage was best, especially for raising children, while the lower educated viewed cohabitation as more normative. In Russia, religion was again expressed in a different way. Orthodox Christians referred to a three-stage theory of relationships: Cohabitation is for the beginning of a relationship, registered official marriage comes soon after, and finally, when the relationship has progressed, a church wedding represents the ultimate commitment. Russian participants also discussed how cohabitation and marriage were linked to the concept of trust, which reflects the general state of a society in which individuals have difficulties trusting each other and institutions (Isupova Reference Isupova2015).

Finally, in some countries, cohabitation was much more prevalent and the focus group participants referred to cohabitation as the normative living arrangement. In Norway, cohabitation and marriage were nearly indistinguishable, especially after childbearing. Nonetheless, marriage was not eschewed altogether, and some still valued it as a symbol of commitment and love. Although marriage is increasingly postponed to later in the life course, often even after having children, it is still seen as a way to celebrate the couple’s relationship. In eastern Germany, on the other hand, marriage held very little symbolic value. The focus of relationships was more on the present rather than whether they would last into the future, and for the most part, participants in eastern Germany thought marriage was irrelevant. Klärner (Reference Klärner2015) speculates that the disinterest in marriage is due to the influence of the former socialist regime, which devalued the institution of marriage, but high levels of nonmarital fertility also have historical roots in the Prussian past (Klüsener and Goldstein Reference Klüsener and Goldstein2014), again suggesting that culture shapes behavior.

Given the unique set of discourses within each country, it is difficult to determine which specific social, economic, or legal factors influenced the responses in each country. Some general patterns emerged, for example, in countries with more similar legal rights, such as Norway, cohabitation was perceived to be mostly similar to marriage, while in countries with fewer protections for cohabitants, such as Poland, focus group participants considered cohabitation to be an unstable relationship. However, the association with legal policies was not clear-cut – for example, discourses in eastern and western Germany differed, even though both regions fall under the same marital law regime. Further, despite the lack of legal differences between de facto partnerships and marriage in Australia, many respondents still valued marriage. These cross-national observations again provide evidence that a complex array of cultural and historical factors shape family behaviors.

Despite the distinct discourses expressed across Europe, however, some common themes emerged, which suggests that cohabitation does share an underlying meaning across countries. First, participants in all countries generally saw cohabitation as a less-committed union than marriage, saying that marriage was the “ultimate commitment,” (United Kingdom), “one hundred percent commitment” (Australia), “higher quality” (Russia), or “more binding and serious” (Austria). Several distinct dimensions of marriage were revealed, for example security and stability, emotional commitment, and the expression of commitment in front of the public, friends, and family. Participants in some countries also discussed fear of commitment, especially among men, and due to the increase in divorce (see also Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Berrington, Gassen, Galezewska and Holland2017a). Although the expression of commitment through marriage was a major theme in most countries, many participants pointed out that other factors, such as owning a house or having children, were just as, if not more, important in signaling commitment. In addition, in nearly every country, a few “ideological cohabitants” argued that cohabiting couples were even more committed than married couples, because they did not need a piece of paper to prove their love. Overall, however, these individuals were in the minority, and cohabitation was seen as a less committed relationship than marriage.

Another theme which emerged throughout the focus groups was the idea that cohabitation is a testing ground allowing couples to “try out” the relationship before marriage. Testing was seen as providing the opportunity for partners to get to know each other and separate if the relationship did not work out. In some countries, participants said that cohabitation was the wise thing to do before marriage (Austria), or even mandatory (Norway), but in all countries cohabitation was recognized as a period when couples could live together as if married but (usually) experience fewer consequences if the relationship dissolved. As a corollary, cohabitation was seen as providing greater freedom than marriage, since it was a more flexible relationship. In some instances this meant that partners have greater independence from each other, for example keeping finances separate, and that they can pursue their own individual self-fulfillment – particularly appealing to women who want to escape the traditional bonds of patriarchy. Some asserted that forming a cohabiting partnership was particularly important after a bad experience with divorce. Others said that the freedom of cohabitation permitted individuals to search for new partners and leave the previous partner if a better one comes along.

The focus group discussions suggested that in most of these European countries, marriage and cohabitation continue to have distinct meanings, with marriage representing a stronger level of commitment and cohabitation a means to cope with the new reality of relationship uncertainty. Yet this uncertainty was not expressed with respect to economic uncertainty, as has often been found in US qualitative research (e.g., Gibson-Davis, Edin, and McLanahan Reference Gibson-Davis, Edin and McLanahan2005; Smock, Manning, and Porter Reference Smock, Manning and Porter2005). Although some European participants did discuss the high costs of a wedding, especially in the United Kingdom, they did not say that couples needed to achieve a certain level of economic stability in order to marry. Of course, the format of focus group research may have discouraged individuals from divulging certain reasons for not marrying, and in-depth interviews with low-income individuals may reveal different narratives, but on the whole, the focus group results suggest that the lack of marriage is not primarily about money, but more about finding a compatible partner. Thus, these focus group findings raise questions about whether cohabitation in Europe is quite different than in America, which appears to be experiencing a more extreme bifurcation of family trajectories by social class (Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos Reference Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos2016).

Consequences – Does Cohabitation Really Matter for People’s Lives?

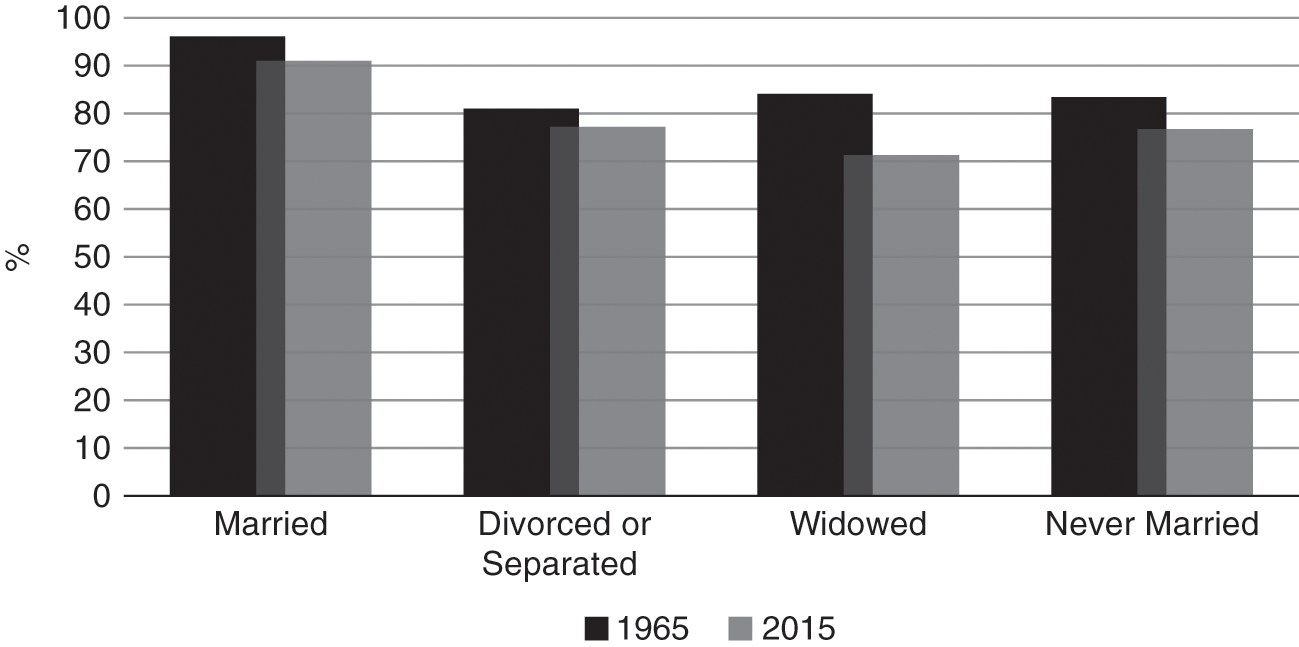

While focus group participants often talked about marriage being a more committed and secure relationship, except in eastern Germany and, to some extent, in Norway, it is not clear whether cohabitation and marriage are truly different types of unions, and to what extent this matters for adult well-being. A large body of research has found that married people have better physical and mental health (Hughes and Waite Reference Hughes and Waite2009; Liu and Umberson Reference Liu and Umberson2008; Waite and Gallagher Reference Waite and Gallagher2000), but many of these studies compare the married and unmarried, without focusing on differences between marriage and cohabitation. Studies that do examine differences between partnership types often find mixed results (e.g., Brown Reference Brown2000; Lamb, Lee, and DeMaris Reference Lamb, Lee and DeMaris2003; Musick and Bumpass Reference Musick and Bumpass2012), still leaving open the question of whether marriage provides greater benefits than cohabitation.

On the one hand, certain aspects of cohabitation do seem to universally differ from marriage. For example, research has consistently found that, on average, cohabiting unions are more likely to dissolve than marital unions (Galezewska Reference Galezewska2016), even if they involve children (DeRose et al. Reference DeRose, Lyons-Amos, Wilcox and Huarcaya2017; Musick and Michelmore Reference Musick and Michelmore2016). Women who were cohabiting at the time of their first child also have lower second birth rates compared to married women, unless they marry shortly afterwards (Perelli-Harris Reference Perelli-Harris2014). In addition, certain characteristics are consistently negatively associated with cohabitation, for example subjective well-being (Soons and Kalmijn Reference Soons and Kalmijn2009) and relationship quality (Aarskaug Wiik, Keizer, and Lappegård Reference Wiik, Kenneth and Lappegård2012). Thus, some differences between cohabitation and marriage do indeed seem to be universal across countries.

Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that many quantitative studies present average associations that do not reflect the heterogeneity of cohabitation or the potential progression of relationships. As discussed above, cohabitation is an inherently more tenuous type of relationship, and many couples use this period of living together to test their relationships. While some of these couples break up, and some eventually marry, many others will live in long-term unions similar to marriage, but without official recognition. Many of these cohabiting relationships can be nearly identical to marriage, providing similar levels of intimacy, emotional support, care, and social networks, as well as benefiting from shared households and economies of scale. Studies of commitment (Duncan and Philips Reference Duncan, Phillips and Park2008) and the pooling of financial resources (Lyngstad, Noack, and Tufte Reference Lyngstad, Noack and Tufte2010) indicate that over time, couples in cohabiting relationships often make greater investments in their relationships, resulting in smaller differences between cohabitation and marriage. Thus, cohabiting relationships have the potential to be identical to marriage, just without “the piece of paper.”

A second key issue that may account for observed differences by relationship type is selection, which posits that different outcomes are not due to the effects of relationship type per se, but instead, the characteristics of the people who choose to be in that type of partnership. As discussed in Chapter 1, many studies find that cohabitants often come from disadvantaged backgrounds, for example their parents had lower levels of education or income (Aarskaug Wiik Reference Wiik2009; Berrington and Diamond Reference Berrington and Diamond2000; Mooyart and Liefbroer Reference Mooyaart and Liefbroer2016) and might have experienced divorce (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Berrington, Gassen, Galezewska and Holland2017a). Selection mechanisms often persist into adulthood, for example men who are unemployed or have temporary jobs are more likely to choose cohabitation (Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn2011), and women with lower educational attainment are more likely to give birth in cohabitation than women with higher educational attainment (Perelli-Harris et al. Reference Perelli-Harris, Kreyenfeld and Kubisch2010). Studies using causal modeling techniques to control for individual characteristics demonstrate that the union type itself does not matter for well-being; instead, the characteristics which lead to poor outcomes also lead people to cohabit rather than marry (Musick and Bumpass Reference Musick and Bumpass2012; Perelli-Harris and Styrc Reference Perelli-Harris and Styrc2018). Thus, although further research is needed to ensure a lack of causality, existing studies suggest that marriage does not itself provide benefits over and above cohabitation, given that the union remains intact. This is very important to note, given the common perception that cohabiting couples are less committed than married couples.

Again, however, cultural, social, policy, and economic context may be very important for shaping these interrelationships. Local and national context may attenuate differences between cohabitation and marriage in some countries but not in others. Social and cultural norms may reduce differences between the two relationship types if cohabitation is normalized with few social sanctions, or widen the gap if marriage is given preferential treatment or accorded a special status. We would expect few differences in behavior or outcomes in the Nordic countries, where cohabitation is widespread (Lappegård and Noack Reference Lappegård and Noack2015), but we would expect substantial differences in the United States where marriage tends to be accorded a higher social status (Cherlin Reference Cherlin2014).