Chapter 1 Locating the theatrical public sphere

In the prologue spoken by David Garrick on the opening of the leading London theatre in 1747, Samuel Johnson imagines the relationship between stage and public as a kind of resonance chamber in which the public voice and theatre exist in a state of reciprocal mimesis. In an age where memories were still fresh from Jeremy Collier’s assault on the very legitimacy of the stage, which in turn harks back to the complete abolition of theatrical institutions a century before, it was perhaps opportune to remind spectators that the offerings placed before them were directly related to their own tastes and follies. While the theatre of the mid-eighteenth century still abounded in ‘censure’, its legal foundation was now relatively secure. The public voice was a force to be reckoned with and its outcries were directed not just at individual plays but also at the stage itself. In this period, and the argument holds for probably all European theatres, the theatrical public sphere was located both inside and outside the auditorium. Next to newspapers the theatre was probably the most important genuine public sphere where not just universal human foibles but also issues of the day found expression on the stage.

The questions to be explored in this chapter focus on how the much-debated concept of the public sphere can be adapted more precisely for the theatre. The chapter heading implies that one might be able to find the theatrical public somewhere: if no longer inside the theatre as I have argued in the introduction then perhaps in public spaces. The spatiality of the theatrical public sphere must be calibrated less in terms of concrete spaces than through constantly changing sets of discursive, social and institutional factors. The first of these concerns the distinction between private and public, one of the decisive anthropological, political and economic dualisms regulating Western culture. Theatre is of course a pre-eminent public space but its relationship to the private sphere is less well theorized. One of the arguments of this book is that today the culturally dominant forms of theatre have effectively ‘privatized’ to the extent that conventional distinctions between private and public have been reversed.

The origins of the public sphere lie in antiquity and are intimately connected with the relationship between theatre and the polis. In the light of current debates on the relevance of the public sphere, its putative rational–critical exclusivity to the detriment of more agonistic modes of engagement, we shall revisit the original concept of the agōn as a point of departure for a more theatrically germane understanding of the public sphere. A prerequisite for any public sphere and another notion first adumbrated by the Greeks is the right to speak and to criticize, expressed in the concepts of isêgoria and parrhêsia. Although first developed over two and half thousand years ago, these rights remain today embattled but form the basis for any concept of the theatrical public sphere. In the final sections, the relationship between theatre and protest will be discussed. Against the background of the Arab Spring and other mass movements of protest, it is useful to revisit the theatre’s function as a forum of protest and intervention. Because protest has historically often been directed against the institution of theatre, as much as against particular plays and performances, the final section will discuss the concept of the theatrical public sphere in terms of its ‘institutional matrices’.

From public to private

In an autobiographical note Jürgen Habermas emphasizes two types of publicity (Öffentlichkeit). The first kind refers to the public exposure demanded by a mediatized society linked to staging practices of celebrities with a concomitant erasure of the borders between private and public spheres. The second type, more narrowly the public sphere in the theoretical sense, refers to participation in political, scientific or literary debates where communication and understanding about a topic or issue replace self-fashioning. In this case, Habermas writes, ‘the audience does not constitute a space for spectators and listeners but a space for speakers and addressees who engage in debate’.2 The former is predicated on spectacle, the latter on discursive communication.

The excessive, voyeuristic publicity of celebrity entertainment can be seen as an example of a degenerated public sphere because in the Habermasian formulation the latter is linked as much to concepts of privacy and intimacy as it is to outright public visibility. And this intimate sphere, as Habermas repeatedly stresses, is bound up with an ‘audience-oriented [publikumsbezogen] subjectivity’, by which he means publicly accessible ‘products of culture’ that explore such psychological questions: ‘in the reading room and the theatre, in museums and at concerts’.3 The bourgeois private sphere stands in a productive and enabling relation to the emergence of a public sphere in the eighteenth century. The transformation (or disintegration) of the public sphere is therefore linked to changes in the private/intimate sphere, which becomes increasingly subject to the pressures of capitalism and reorganization of labour. Consequently, the private realm also becomes separate from the public sphere, and, as Richard Sennett famously argues in The Fall of Public Man (Reference Sennett1977), gradually comes to occupy and dominate bourgeois life to the detriment of public life. As Sennett demonstrates, the demarcation lines between public and private are not fixed but linked together in ‘complex evolutionary chains’.4 While it is obvious that notions of privateness and the private realm are historically and culturally contingent, this applies also to concepts of publicness, which are additionally dependent on media conditions. Whereas in ancient Greece the agora and the theatre festivals attained the ultimate degree of publicness possible at that time, so that the theatre public and the public sphere were in a sense almost identical, in the age of mass media, nation states and increasingly transnational configurations, even a large theatre auditorium resembles a closed black box rather than a guarantor of public exposure.

In political theory the public is connected to the political realm. Originating in the Roman concept of res publica and the practice of self-government by citizens in an ongoing process of collective self-determination, Roman law developed a notion of the ‘public’ as a category of collective ‘good’. ‘This specification of the “common” as the “public good” was determinant for all subsequent developments of any notion of publicness’ notes Amando Salvatore.5 By extension such a concept of the public as a specific type of good or goods set limits to the private domains of property and patronage on the one hand and to the pater familias on the other. In his discussion of ‘models’ of democracy, David Held further interrogates the problem of limits and borders between the public and what he terms ‘the sphere of the intimate’ which he understands as the realm and circumstances ‘where people live out their personal lives without systematically harmful consequences for those around them’.6 In Held’s reading, this demarcation dispute is fundamental to any discussion of democracy, as it establishes contestable limits to legislation of the private realm. Although the concept of a private sphere is equally as polysemantic and difficult to grasp as the public sphere, it is necessary to engage with this dichotomy and the changing relationship between the private and the public, because theatre mediates between these realms. Both architecturally and in terms of the content presented onstage, plays and performances invariably thematize the private and the public. As Jeff Weintraub points out, ‘the public/private distinction . . . is not unitary, but protean. It comprises, not a single paired opposition, but a complex family of them, neither mutually reducible nor wholly unrelated.’7

The reconfiguration of the borders and distinctions between the private and the public was a determining factor of 1960s counterculture (‘the private is political’) and its subsequent metamorphosis into identity politics, especially in the Anglo-American context and its various New World adoptions and adaptations. Michael Warner focuses particularly on this expansion of the Habermasian notion and its challenge by counterpublics.8 Such counterpublics, represented in Warner’s case principally by gay and queer interventions, frequently redefine the rules regulating the decorum of the private and public. This complex relationship requires therefore a plurality of perspectives which combine architectural as well as changing social notions of private versus public. These two perspectives are in turn intertwined and imbricated in the modernist shift in theatre from which we are only just emerging.

In pre-modernist European contexts, theatre is a space of social encounter and communication. The architectural structure of seats and boxes, camerini, foyers and sweeping staircases index a complex set of interlocking spaces of which the stage itself is only one, and perhaps not even the most important. This form emerged in Venice in the seventeenth century, where it corresponded to the needs of the new genre of commercialized opera aimed at a stratified society. It became established throughout Europe with variations during the eighteenth century and remained – again with variations – dominant until the beginning of the twentieth century. This was a theatre of light – performances were still not possible in complete darkness – and social communication and display. Sightlines were directed from box to box and parterre as much as they were towards the stage. Of course the stage remained the main focus of attention but the auditorium in its different sections was an equally important space if we think of the theatre as – at least potentially – a part of the public sphere along with newspapers and coffeehouses, clubs and political gatherings.

In the nineteenth century theatres were places where many people gathered – usually between 1,000 and 2,000 in number. In terms of their capacity to house large gatherings, they were rivalled only by churches and cathedrals. In an era pre-dating sports stadiums, theatres were perhaps the only architecturally fashioned public spaces in existence. In the New World we find in this period the emergence of town halls as new public spaces, which often doubled as places of performance. The inherent publicness of theatre made it a natural object of political control. This control – usually in the form of licensing and censorship – was directed in the first instance towards the performances onstage. However, the audience itself was always a source of potential unrest and worry for authorities as the temptation to address and incite such a large gathering was often too great to resist. The ability of theatrical representation to bypass the conventions of rational debate – the reasoned exchange of opinions formulated in writing between educated gentlemen, in other words the classical Habermasian public sphere – made it an extremely protean and unpredictable factor in public life.

This unpredictability and with it theatre’s social and political significance begin to diminish in the second half of the nineteenth century with the rise of the modernist movement’s calls for a theatre adhering to artistic principles. In this period, a crucial shift towards smaller audiences and a more intimate relationship between spectators and performers begins to develop. Auditorium and stage provide the model for the cinema, which developed its own spatial specificities out of the theatre, often occupying theatrical spaces as they became less profitable and vacant. Of central importance is the modernist turn to the smaller intimate space immersed in darkness following Wagner’s famous requirements for the Bayreuth stage. Wagner’s injunction to focus concentration on the stage and remove all other extraneous sensuous stimuli provided the model for most forms of art theatre until this day. Whether art-deco intimate, pseudo-Greek amphitheatrical, proscenium arch commercial or subsidized experimental black box, the modernist art-theatre model is predicated on the aesthetic, not the social experience. Its audience is ideally a highly concentrated decoder of signs and auto-reflexive observer of self-experience. Essential interiority and concentrated attention are central features of modernist spectating.9

This form starts its journey in the late nineteenth century – we can perhaps take André Antoine’s relatively intimate Théâtre Libre as a point of departure – and is disseminated throughout the world, partly on the coat-tails of colonial expansion, partly through processes of transnational modernization as local elites looked to Europe for models. Within the wider processes of modernization in the first half of the twentieth century the cinematic stage comes to be a synecdoche of the theatre itself. One of the many implications of this reduction of the theatrical medium to smallish darkened rooms was the virtual eradication of theatre’s many potential public functions. Once the doors are closed and the lights are down, theatre becomes an intimate private space where collective response is certainly felt and registered but is subsumed to the dominance of artistic production onstage. As a public sphere it becomes practically defunct, bar the occasional scandal, as the semiotic dynamics at work on the art-stage transform everything into a sign of a sign. Those things which resist recoding or remain, phenomenologically speaking, stubbornly en soi – children and animals for example – are discarded and/or expelled from the realm.10

The publicness of theatre is therefore a highly contingent phenomenon that we should not take for granted, but rather study more closely in relation to the private and the public spheres. As I shall argue in Chapter 5, the gradual abolition of censorship in the course of the twentieth century indexes this shift from public to private. Just as the advocates of naturalistic theatre defined the performances as clubs accessible only to private members, so too do theatres today claim for themselves under the auspices of artistic freedom the status of being a quasi-private realm. If, then, what happens between stage and auditorium is comparable to that of activities between consenting adults, theatre’s definition as a public sphere needs to be reassessed and modulated more precisely.

The relationship between private and public is today more than just an architectural function or aesthetic attitude; it is also related to wider questions of theatre’s place in society. The dichotomy between public and private also has economic and social dimensions that are equally conflictual. The definition of theatre as a modernist art form parallels two interconnected developments: the gradual but inexorable shift to public support of theatre, and the concomitant loss of its commercial (private) character, although the relationship between the two varies greatly between countries and cultures. A central thesis of this book is that we are poised on the brink of an axial shift in regard to theatre’s function within the private–public divide. This refers as much to economic and political concerns – debates over public funding and private engagement (sponsorship, patronage) – as it does to the spatial understanding of a theatre performance being intrinsically public.

Towards an agonistic public sphere

Since the public sphere is fundamentally a political concept, it is logical that discussion inevitably refers back to classical Greek models, whether it is the agora as the space of open debate, or the theatre of Dionysus with its apparent ideal equation of citizenry and audience. Habermas also sees the roots of the idea in the Greek polis:

In the fully developed Greek city-state the sphere of the polis, which was common (koine) to the free citizens, was strictly separated from the sphere of the oikos; in the sphere of the oikos, each individual is in his own realm (idia). The public life, bios politikos, went on in the marketplace (agora), but of course this did not mean that it occurred necessarily only in this specific locale. The public sphere was constituted in discussion (lexis), which could also assume the forms of consultation and of sitting in the court of law, as well as in common action (praxis), be it the waging of war or competition in athletic games.11

The normative power of the Renaissance model of the Hellenic public sphere was, Habermas argues, ‘handed down to us in the stylised form of Greek self-interpretation’.12 Apart from a laconic, Marxist nod to the ‘patrimonial slave economy’ as the foundation of this leisure-based political order, Habermas makes only oblique references to the classical model in his book. This is understandable as he is primarily concerned with a new form of public sphere, the rational–critical bourgeois variant that, according to his argument, only emerges in the eighteenth century and was no longer reliant on face-to-face communication but functioned through the print media. It is worth noting that in the above quotation theatre is not mentioned at all, although other performative phenomena are recognized as belonging to the public sphere, notably trials and games. The importance of the Greek legacy lies in the distinction between polis (wherever it may be enacted) and oikos, the domestic realm.

To what extent then were the performances in Greek theatres a constituent part of the public sphere is this nascent form? What is the relationship between the spatial realm of the theatron and the agora? We can justify this brief excursion into antiquity because of its model character and ‘normative power’ for post-Renaissance theorizations – although less so in its practical applications – of the public sphere. A considerable body of recent research has engaged at least implicitly with the concept of the public sphere in the context of Greek theatre.

Ever since Nietzsche’s emphatic visualization of the aroused Dionysian spectator in The Birth of Tragedy, and its many emulations in the 1960s, we tend to imagine that Greek citizens experienced each other in a state of collectivity and heightened community, if not downright Dionysian ecstasy. From revolutionary France to the student revolt of the late 1960s and their theatrical ramifications, we find idealizations of Greek theatre as an ideal–typical public sphere. The image of theatre as a collective gathering of citizens without regard to rank or education remains the most persistent model for understanding Greek theatre in its time and as a theatre reform model in our own.

If we examine the extant evidence and review recent research, there is enough testimony to suggest that Greek theatre festivals did indeed create a public sphere in some of the senses used in this book. We shall need to look at two key concepts – agōn and parrhêsia – as a means not just to understand Greek theatre but to formulate more precisely a concept of a theatrical public sphere. In their interlocking functions the two terms suggest that Greek theatre was much more than just an aesthetic experience (which will come as no surprise to most readers) but deeply imbricated in the wider complexities of the polis. We can also find support for the idea that representative, rational–critical and agonistic public spheres were at work in the complex dynamics of these performances and their institutional frameworks. To understand these dynamics however, and to locate the public sphere in Greek theatre, it is necessary to expand our perspective beyond the actual performances of the dramas and look at the cultural and institutional frames within which the plays were enacted.

The representative public sphere, which is based on the display of power before an audience, is primarily indexical in function. It assumes a direct visual connection between sign and signified, and attains thereby its political potency. Its symbolic signs are subordinated to the immediate power of optical proof. The anthropologist Victor Turner once made a useful distinction between ceremonies and rituals: ‘ceremony indicates, ritual transforms’.13 On the basis of this distinction, we must regard the theatre festivals, in particular the City Dionysia, as primarily ceremonial and indexical, rather than ritualistic, although the latter provided the residual traditional framework. Within the often described four-part structure – procession and sacrifice, pre-performance events, the performances themselves and some sort of follow-up14 – the second and fourth parts are primarily of interest, because they contain the framing context for an incipient theatrical public sphere. Before the performances took place, processions and proclamations were enacted in the theatre orchestra, which were primarily political and indicative. The Athenian allies from the many colonies constituting the Athenian Empire displayed their annual tributes. Ephebes (war orphans raised by the city) paraded in armour and took their specially reserved seats to watch the performance. Sometimes officials announced the names of recently freed slaves, thereby documenting their new status. All these events were demonstrated before a public, and attained thereby official recognition, analogous to the public demonstration before a court of law.

The festival concluded with another ceremony where the winners of the agōn were announced, the prizes awarded, and the festival itself evaluated. The final event was a meeting of the Athenian assembly, the central political organ of the city, which normally met at a different location, the Pnyx. All these post-performance meetings and deliberations underline the important discursive aspect of the festivals. This discursive and critical dimension was a direct result, however, of the agonistic framework. The performances were competitions and, as Rush Rehm has argued, this competitive frame determined audience response: ‘The festival’s competitions introduced a critical element into the audiences’ response, reinforcing their role as democratic citizens determining their city’s future.’15 In the concluding meetings, then, and this is a direct result of the agonistic mode, we are approaching something close to a concept of a rational–critical public sphere, although not separated out but rather imbricated in a more integrated set of cultural practices, which today we would see as being quite distinct from one another.

If we look more closely at the term agōn, we can see that it provided a cognitive framework closer to critical and discursive deliberation than to the highly affective dynamics of cathartic release at work in the performances themselves, at least in the tragedies. The comedies with their satirical parabases clearly operated in a different mode again. The agōn and its root word, agōnia, is a concept ubiquitous in discussions of Greek culture generally, and theatre in particular. The term is suffused with performative connotations: apart from competition, it also means assembly, action, debate, legal action and argument. The Liddell–Scott Greek–English Dictionary lists no fewer than seven different, although semantically related, meanings. We find it applied as a term for individual actors (characters are termed protagonists) and in an institutional context: the selection of plays to be performed took place in a ceremonial pro-agōn. All these forms indicate the all-pervasive theatrical nature of the agonistic principle. It is perhaps no surprise that nineteenth-century scholars also applied the term to describe a structural element of Old Comedy. The balanced debate characteristic of Aristophanic Comedy has also been termed an agōn, in which arguments are exchanged and the main dramatic issue is presented.

Even if we restrict ourselves to the emic uses of the term, i.e. those used by the Greeks themselves, we find an overarching principle linking theatrical performance and public life. If, as we have argued, the theatre festivals were seen as another variation on or of the polis, then the agōn is its connecting principle. It is both performative and cognitive inasmuch as the same overriding principle pertained in seemingly disparate activities. In this sense an agōn generates and reformulates publicity. Every public interaction is considered a political act and as such is placed in opposition to private acts (idiai). The fact that political assemblies in the narrower sense of the term were in fact conducted in the context of a theatre festival supports the argument made by scholars such as Simon Goldhill that institutions like the law courts, assemblies and theatre performances were all in a sense political. All the ceremonials described above promoted and projected (in the literal sense of the word) forms of citizen participation in the state: ‘To be in an audience is above all to play the role of democratic citizen.’16

The term agōn has undergone significant semantic movement since antiquity. Leaving aside the primary meaning of extreme physical pain (agony), the cognate term agonistic retains its competitive and combative overtones and can denote striving or straining for effect as well as eagerness to win an argument. In the arena of political theory, the post-Marxist theorist Chantal Mouffe’s theory of agonistic pluralism, as outlined in the introduction, not only implicitly establishes a link back to the original Greek concept but, because it places so much emphasis on affective and ‘passionate’ modes of expression, helps to establish a notion of the public sphere, amenable to the theatre. By integrating affect and the ‘passions’ into the public sphere, Mouffe prepares the ground for an extended notion of the public sphere, which is both theoretically and historically compatible with the medium of theatre. Despite her criticisms of Habermas, the agonistic principle she espouses is less antithetical to his concept than she supposes. The most important difference relates to the inclusion of less rationalistic modes of argumentative exchange. Although Mouffe scarcely engages with the theatre, except in a metaphorical sense, she recognizes the importance of performative protest as an example of an agonistic public sphere. In an essay entitled ‘Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces’ (Reference Mouffe2007) she defines ‘critical art’ such as that practised by ‘Reclaim the Streets’ in the UK or ‘The Yes Men’ in the USA as ‘art that foments dissensus, that makes visible what the dominant consensus tends to obscure and obliterate. It is constituted by a manifold of artistic practices aiming at giving a voice to all those who are silenced within the framework of the existing hegemony.’17 While Mouffe would probably only acknowledge a very small section of theatrical activity as ‘agonistic’ in her definition of the term, I would like to argue that, from a historical perspective, the agonistic, when linked to its original and more inclusive Greek meaning of the word, can be regarded as a principle providing a missing link between the rationalistic, consensus-oriented understanding of the public sphere where only certain kinds of speech acts are functional, and a concept where affective modes of expression are equally permissible.

Acting the truth: parrhêsia

Freedom of speech and the right to express one’s opinion without fear of recrimination are preconditions of any modern conception of a critical public sphere. This right also has its foundation in specific institutions of Greek political culture. Two concepts are of interest here: isêgoria and parrhêsia. The former refers to the equal right of speech to address the political assembly, whereas the latter denotes the right to criticize or, more generally, freedom of opinion. Isêgoria guarantees the right to speak and is therefore a formal principle, whereas parrhêsia regulates the content of what can be said. While both are evidently fundamental for a modern understanding of the public sphere – equality of access and freedom of opinion – they are equally crucial for understanding Athenian democracy. All citizens (i.e., not slaves, women, foreigners, children) have through isêgoria the right to speak and be heard. In this sense it seems to have been a fairly accepted right. A more contested concept is parrhêsia because it may refer ‘either (1) to a political (or otherwise social) situation in which one is free to speak one’s mind (“freedom of speech”), or (2) to the activity, attitude, or quality of an individual (“free speech”, “frankness”)’.18 It is particularly the second variation in Marlein van Raalte’s definition that was controversial, even in antiquity. What are the bounds of ‘frankness’? Where does parrhêsia end and libel and slander begin? In his famous lectures given at the University of Berkeley in 1983, Michel Foucault reinvested the concept of parrhêsia with contemporary meaning, which provided in turn an important reference point for recent debates on hate speech, freedom of opinion and the boundaries of the public sphere in multicultural societies. Foucault interrogates the concept in the context of what he terms ‘governmentality’, the interdependence of the modern sovereign state and the modern subjectivity of the autonomous individual. The act of parrhêsia is not just an abstract principle but, because it ultimately implies that the speaker is telling the truth, is fraught with risk: ‘Parrhêsia, then, is linked to courage in the face of danger: it demands the courage to speak the truth in spite of some danger. And in its extreme form, telling the truth takes place in the “game” of life or death.’19

In his reading of Euripides, to bring the discussion back to the theatre, Foucault argues that the practice itself had become problematic, reflecting in turn a crisis of Athenian democracy. Its repeated thematization in Euripidean drama, most notably in Ion, onstage in full view of the Athenian populace as it were, reflects a problematic relation in a key practice of the democratic system: ‘the crisis regarding parrhêsia is a problem of truth: for the problem is one of recognizing who is capable of speaking the truth within the limits of an institutional system where everyone is equally entitled to give his or her own opinion.’20

Foucault’s analysis of parrhêsia suggests very strongly that certain elements of the theatrical public sphere that we tend to associate with much later institutional developments were in fact already present in Greek theatre. This refers not only to the context of the festivals in which a number of cultural practices such as the theory and the institution of the assembly were carried out, but also to more fundamental questions of democratic institutions such as isêgoria and parrhêsia which are in turn reflected in the dramas enacted in the context of the festivals. Here we find an interlocking of the inside and the outside, of the audience as public, and the public as a public sphere.

What Foucault does not explicitly engage with is the institutional frame of parrhêsia enunciated onstage. While Euripides reflects on parrhêsia in his tragedies, he does not explicitly use the theatre as a place in which to make use of the right. This section’s heading (‘Acting the truth’) alludes to the ambivalent status of the theatre as a space for truth-telling. To contemporary ears, although this may have been quite different in antiquity, the phrase ‘acting the truth’ has an oxymoronic ring to it. But in Greek theatre the stage was used for parrhêsia. This role appears to have fallen to the dramatists of the Old Comedy, most notably Aristophanes, an author Foucault notably ignores. They rigorously tested the boundaries of parrhêsia in the theatre. In both his plays and his life Aristophanes demonstrated what could and couldn’t be said on the Athenian stage. In Archarnians, the comedy that repeatedly thematizes parrhêsia and isêgoria, the main character Dicaeopolis turns to the chorus and the assembled audience to assert his right of isêgoria and parrhêsia:

His exhortation encapsulates several of the crucial features of parrhêsia: the right of even lowly citizens to speak before the citizenry, the act of courage to utter such things, and the epistemological status of what is said, its fundamental truthfulness.

In an early essay on freedom of speech in Athens, Max Radin examined in considerable detail the dynamics of parrhêsia and its attendant dangers, especially for dramatists such as Aristophanes. Attacks on public figures on the stage were commonplace and the boundaries of libel ill-defined:

There was in Athens a stout politician named Cleonymus. Of him Aristophanes says [in various plays] that he was a perjurer, a catamite, a flatterer, an informer, a swindler, and at least five times, he calls him a ‘shield-thrower’, or its equivalent.22

Of these various derogatory epithets, the charge of ‘shield-thrower’ was the most heinous because it implied cowardice in battle. And, as Radin argues, parrhêsia was not limitless but became in fact subject to legal regulation. Under libel law certain words and phrases were ruled to be apórrēta, quite literarily ‘unsayable’, including the above-mentioned act of shield-throwing, along with murder and father- or mother-beating. Because Aristophanes continually tested the limits of libel by alluding to but necessarily using the forbidden words, it is clear that the stage and the law were already engaged in what was to become a protracted game of cat and mouse that continues to this day. The use of satire, parody and other comic devices bring to the fore the ludic aspect of the public sphere. The act of telling the truth evidently had both deadly earnest and risible dimensions.

The ancient Greek obsession with the truth, its conditions of utterance, its relevance to the democratic process of the polis, its erosion and finally its repeated treatment onstage all point to deeper inner connections between the theatre, the public sphere and fundamental civic issues of truth-telling. The issue remains as virulent as ever. The inner connection between theatre, truth-telling and the public sphere was brought home to South Africans in 1995 with the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up to work through the traumas of the apartheid regime. Over the roughly two years of its operation, South African citizens were exposed to and had a profound experience with institutionalized and mediatized truth-telling.23 The work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission demonstrated parrhêsia in action, its performative as well as propositional dimensions. Of the many truth commissions that have operated since 1974 to formally investigate and report on human rights violations, the South African one has engendered the most varied media responses: books, plays, films, both documentary and fictional, have emerged from and responded to its deliberations. Theatre productions such as Ubu and the Truth Commission, The Story I Am about to Tell, or Truth in Translation, Rewind: A Cantata for Voice, Tape and Testimony, all reveal quite different aesthetic approaches to the same fundamental situation: the giving of testimony in a public arena, that William Kentridge has termed a kind of ‘ur-theatre’.24 Whether the performers are identical with the testimony givers, as in The Story I Am about to Tell, or represented by puppets, as in Kentridge’s Ubu and the Truth Commission, each production throws up a number of ethical and aesthetic issues that have been intensely debated over the past years. The Truth in Translation project visited Northern Ireland, Rwanda, Bosnia, while The Story I Am about to Tell was expressly designed for ‘travel around and between communities small and large to spread awareness about the Commission and engage citizens in debate around the questions that it raised’.25 This self-description contains a textbook definition of a public sphere.

The unremittingly public nature of the actual testimony sanctioned what was said as parrhêsia. In the words of Juan Méndez, who launched Human Rights Watch’s (HRW) Americas Program: ‘Knowledge that is officially sanctioned, and thereby made “part of the public cognitive scene” . . . acquires a mysterious quality that is not there when it is merely “truth”.’26 Knowledge communicated within a public, one could almost add, theatrical, framework such as the Truth Commission redefines and revalorizes the truth, raising it from the status of being ‘merely truth’ to truth spoken under the conditions of public scrutiny, where staged truth becomes witnessed truth and is thus sanctioned as parrhêsia.

Protest and intervention

Periods of tumultuous change, such as transitions from dictatorships to democracy, are particularly conducive to both the exercise of parrhêsia, in order to expose the atrocities of the former regimes, and the use of theatre as a forum to publicize such deeds. The French Revolution, with its explosive mixture of deregulated theatres, revolutionary plays and festivals, impassioned political debates, public executions and street protests, provides an almost overdetermined example of an agonistic theatrical public sphere. Susan Maslan has drawn attention to the contradictory status of actual theatre in the context of the revolution. On the one hand, the restrictions of the ancient regime had been lifted, licensing procedures removed, and many new theatres had been established. On the other hand a number of the leading revolutionaries, most prominently Robespierre himself, were heavily influenced by Rousseau’s anti-theatrical tract, Lettre à d’Alembert (1758), which questioned the very institution of theatre, at least in its function and practice of staging fictional stories. Maslan traces the vigorous debate that emerged around the function and legitimacy of theatre that was caught between ardent advocates and equally impassioned opponents. Here we see not just particular plays engendering opposition or even riots, but a debate centring around the very institution itself. These debates highlight the fact that the auditorium was seen as a potential public sphere and crucible for the formation of public opinion. Depending on the point of view, its strength or respective danger lay in the ability of theatre to create a community, stoked by its much-feared capacity to whip up collective feeling and generate affective arousal. Theatre was able to do something print could not; ‘it could forge communities of sentiment’.27

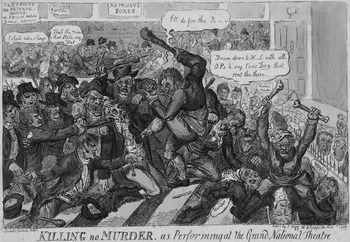

Although the French Revolution stands out as ‘protest theatre’ in almost all its imaginable forms, and despite the political rather than aesthetic orientation implied by such a concept, a theatrical public sphere is not, however, necessarily synonymous with ‘contentious performances’28 or vociferous protest. There exists nevertheless a long-standing, almost innate connection between dissidence and the public sphere. In classical Latin prōtestari means to declare or bear witness in public, and hence to testify. Although not etymologically linked to dissent, the semantic shift in the sense of a formal expression of disagreement emerged by the seventeenth century.29 The current understanding of protest as a public demonstration of disagreement is not registered in English until the nineteenth century.30 That the theatre itself could become a forum for protest had, however, long been recognized by authorities, who preferred terms such as ‘disturbance’, ‘disorder’ or ‘riot’ when the audience became unruly. When the ire of the public is turned against the theatre itself as in the famous Old Price Riots in Covent Garden in 1809, when spectators violently opposed a new pricing scheme, the theatre becomes institutionally a subject matter of the public sphere. As can be seen in George Cruickshank’s famous caricature, ‘Killing No Murder; as Performing at the Grand National Theatre’, dissent was articulated by direct corporeal intervention rather than through verbal means. The Habermasian ideal of achieving rational consensus by reasoned debate was still in an embryonic stage (Figure 2).31

2 Finding rational consensus during the Old Price Riots, Covent Garden Theatre, London, 1809

While regimes of censorship always implicitly acknowledge theatre’s potential to foment unrest and thereby try to stifle the stage’s function as a platform for articulating issues of public interest, the theatre has always endeavoured to bypass such restrictions. Whether through allegorical allusion or by impromptu asides, the stage finds ways to capitalize on its function as a public gathering. The question today, however, especially in those societies where there is little or no censorship, seems more to be whether it has any function at all. Whether in fact the directness of communication inherent in protest is compatible with the complexity and ‘enigmatic’ character of aesthetic experience (Adorno),32 remains a disputed question, particularly in the field of political theatre. It is certainly one of the reasons, the Piscatorian–Brechtian model in its overly simplified, ideologically unambiguous manifestations, has fallen out of fashion. The documentary theatre of the 1960s certainly had the capacity to engender public debates, if we remember the controversies surrounding plays such as Rolf Hochhuth’s The Deputy (1963), or the protests that frequently greeted works by Marxist writers like Peter Weiss in the polarized publics of Cold War Europe. Weiss regarded theatre as the more efficacious forum for public debate in the light of mass media controlled by capital. The mode of 1960s documentary theatre however provided very little capacity for genuine, two-way communication. This is a shortcoming it shares with more contemporary forms of politically inflected drama such as verbatim or testimonial theatre.

Can the theatre be refashioned as a forum for public debate? The concept of ‘forum theatre’ developed by Brazilian director and political activist Augusto Boal reflects this critical potential in its very name. In forum theatre a ‘model scene’ thematizing a social or political problem is performed before an audience in at least two versions. After the first version the spectators are given the opportunity to not just make suggestions for alternative solutions but to actually intervene as performers and replace the trained actors. The aim is to not just raise consciousness but also to activate the desire for real-life invention. Forum Theatre creates a virtual public sphere in as much as debate and discussion are initiated on an issue of interest to the participants, which in practice tends to be localized and specific. Closer to the public sphere are those forms that Boal groups under the term ‘theatre as discourse’ such as ‘invisible’ theatre. Here scenes from daily life are staged without the knowledge of passers-by who witness and ideally intervene in them. The scenes are supposed to transform an everyday space into a ‘public forum’ by engendering discussion on an issue.33 In both forms key aspects of the public sphere are virtualized or, to use Boal’s term, ‘rehearsed’ by dissolving the usual performer–spectator distinction.

A more complex virtual integration of the public sphere and theatrical performance was achieved by Peter Sellars in his project The Children of Heracles (2002–7). Designed as a protest against the treatment of refugees, in particular children, in Western countries, it varied a common structure in its several iterations. The version I saw in Amsterdam in 2004 during the Holland Festival consisted of a performance of the play by Euripides preceded by a panel discussion with local experts and a member of the local refugee community. Throughout the performance a chorus of young people drawn from a nearby refugee camp sit mostly silently onstage regarding the audience. After the performance Sellars engaged in a discussion with the public. Other versions concluded with a shared dinner in a local restaurant. In repeated interviews given in connection with the production Sellars emphasized the archetypal nexus between theatre and democracy in ancient Greece. Sellars argued that theatre was in fact an extension and even enhancement of democratic process. Although most commentary on the production has tended to focus on the ethical implications of using ‘authentic’ asylum seekers onstage, the more apposite question is the new format he developed. Aware of the aporia inherent in ‘spectacle-theatre’ (Boal), The Children of Heracles production combined different modes of discursive engagement with the issue of refugees, which the mass media have forfeited. In Joshua Abrams’s assessment, the production with its ‘interplay of logic and affect’ has almost the potential for reimagining and redefining ‘an ethical public sphere for the 21st-century’.34

The task is, however, a difficult one. In an interview given for Dutch television, Sellars was asked: ‘Are you an artist or an activist?’35 The question implied that engagement with the wider public sphere by artists requires a choice not a combination. The exclusionary ‘alternativelessness’ echoes one of the arguments of this book, namely that theatre in its contemporary versions has become successful as establishing itself as an art form and is thus ill-designed for activism or other instrumental ends. Sellars’s production enables the spectator in theory to switch between three roles: the informed listener (panel discussion), the aesthetic spectator (performance of the play) and the actively involved discussant (post-performance discussion). While all three are familiar, their combination in one production adumbrates one possible strategy for creating a public sphere inside the theatre.

Most protest theatre and performance is enacted in nontheatrical spaces and joins forces with activist performance, often blurring the distinctions between social art and activist politics. Particularly in the United States there has emerged a plethora of groups and initiatives, which use a broad range of contestatory tactics to engage with political or corporate opponents. They include Patriots against the Patriot Act, Billionaires for Bush, the Yes Men, the Church of Life after Shopping and the Clandestinely Insurgent Rebel Clown Army (CIRCA). Most of these groups emerged in response to the repressive atmosphere in American media politics following 9/11, where, in a striking confirmation of Peter Weiss’s thesis, most forms of dissent were effectively silenced in the mainstream media. Broadly speaking, the groups utilize various forms of subversive mimesis to simultaneously affirm and negate the objects of protests: politics, corporate exploitation or consumer society.36 Such activist collectives will not feature prominently in this book because the focus is, as already stated, on the institution of theatre and less on informal protest practices. The activities of such groups, which work on the streets or in the media, confirm indirectly the perceived political ineffectiveness of theatre. They use theatrical means to gain access to the public sphere in one way or another but seldom avail themselves of the theatre itself.

The political turmoil and climate of crisis following 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq by the ‘Coalition of the Willing’ in 2003 did in fact lead to a temporary revitalization of the theatre as a public sphere in the US and the UK. David Román notes: ‘Going to the theatre meant participating in a collective but fleeting effort to create a counterpublic space of emotion and affect that differed from the violent rhetoric of nationalism increasingly evident in the aftermath of September 11.’37 Marvin Carlson has written about the other coalition of the willing, Theaters Against War (THAW) initiated by an activist organization, Not in Our Name, which organized theatre events to protest against Bush’s War on Terror.38 The highpoint was a global event on 3 March 2003 whereby more than a thousand readings of Lysistrata took place simultaneously in fifty-six countries.39 In a recent survey of protest theatre Jenny Spencer speaks indeed of the ‘self-censoring silence’ of theatre artists, first in New York and then in the UK after the terrorist attacks of 7/7 before theatres finally began to organize themselves as forums for protest.40 Such events, even those on a global scale harnessing new technologies like Lysistrata, confirm ex negativo the problematic relationship between the theatre and the public sphere. If it needs a catastrophe on the scale of 9/11 or an American-driven war to activate such energies, then it must be asked what conditions pertain in the institutional everyday.

Institutional matrices

The institutional core of the public sphere comprises communicative networks amplified by a cultural complex, a press and, later, mass media; they make it possible for a public of art-enjoying private persons to participate in a reproduction of culture, and for our public of citizens of the state to participate in the social integration mediated by public opinion.

The classical formulation of public sphere theory sees the public sphere and institutions as tendentially antithetical entities. Although Habermas places the public sphere between the free market economy and the state, the citation above makes clear that the public sphere itself comprises institutions, both private and public, which interact to enable the communication that lies at its core. Most scholars have little difficulty in thinking of theatre as an institution – even if most are not particularly interested in that aspect of the medium – yet there has been little work done in actually defining the concept of institution in relationship to theatre.42 This reticence is partially due to a theoretical tradition focused on defining or isolating any smallest common denominator, applicable to all manifestations of theatre from the Greeks to the present, from classical nô to Vietnamese water puppets. The most famous articulation of this broadly phenomenological project is of course Eric Bentley’s relentlessly cited formula of A watching B while C looks on. And while even that basic equation is no longer consensual in today’s postdramatic, highly mediatized performances, it never really proved very useful for thinking about theatre in anything but the crudest cognitive terms.

If we are going to examine the public sphere and its relationship to the institutional aspects of theatre, then we have to review the term ‘institution’ and try to identify some of its dimensions. Even a quick survey of possible definitions immediately reveals an extraordinary range. The Oxford English Dictionary lists at least eight discrete fields. They show that there is no one single prêt-a-porter definition encompassing social anthropology, sociology, political economy and the arts. While a social anthropologist may recognize social behaviours such as shaking hands as an institution in a particular cultural context, most understandings of the term see more complex social interaction as a prerequisite for the concept.

There is broad agreement that institutions are at root ‘rules’. In the famous phrase of the economic historian Douglass North, institutions are ‘the rules of the game in our society or, more formally, the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction’.43 Rules and constraints figure prominently in most definitions and assume collective behaviour of some sort because individuals do not normally impose rules on themselves and of their own volition. Institutions form an intermediary level between individual actions and collective practice, which place constraints on the former and give regularity and predictability to the latter. For our purposes three main interrelated features can be identified: duration, legal status and supra-individual functionality. Durationality is a hallmark of institutions both in the colloquial sense of the word (something or someone is considered an ‘institution’) and in a stricter sense of existing over time. The notion of duration is determined to a large degree by a legal status that goes beyond just a deed of sale. In this sense a privately operated theatre is seldom an institution, although there may be exceptions to this. On the other hand, legal provisions may engender the creation of an institution in the sense of providing a secure juridical framework within which theatres may operate. In the latter sense we could argue that the Elizabethan public theatres collectively were an institution enabled and regulated by a series of laws such as the 1572 Act for the Punishment of Vagabonds. Similarly we can speak of the Athenian Dionysian festivals as providing an institutional framework, although we are not aware of a specific law enabling them. There existed rather a body of cultural practice of quasi-juridical status. Most importantly, all these examples point to practices that function independent of particular artists or entrepreneurs. In comparison to artist-centred operations, institutions, even theatrical ones, normally continue to function independent of whoever is running them.

The most complex research on institutions has emerged, not surprisingly, in the fields of sociology and political economy. Max Weber’s normative emphasis on institutions as a precondition for modernity set the tone for research in both disciplines and certainly reinforced the popular conception linking institutions with administrative bureaucracy on the one hand and reliable legal frameworks on the other. The most important development over recent decades has been a questioning of such Weberian precepts, a move that is encapsulated under the loose umbrella term ‘new institutionalism’. If older institutional theory placed its main emphasis on values, norms and a broadly understood belief in conscious human action and design underlying institutions, then new institutionalism emphasizes the importance of unconsciously embodied schemas and scripts that determine how institutions actually function and explain the stasis we normally associate with them. In the words of two leading theorists of this field, Dimaggio and Powell, ‘not norms and values but taken for granted scripts, rules, and classifications are the stuff of which institutions are made . . . institutions are macro-level abstractions . . . cognitive models in which schemas and scripts lead decision-makers to resist new evidence’.44 This neo-institutional definition emphasizes a structural tendency towards replication and stasis rather than innovation, to reinforcing the status quo rather than seeking the shock of the new. By its very definition the term institution is inimical to our preferred understanding of theatre as a bubbling cauldron of resistance, subversion and perpetual innovation.

To say that ‘institutions are macro-level abstractions’ is another way of demarcating the distinction between institutions and organisations. Here too most institutional theorists agree that the distinction must be drawn, even though the two terms are symbiotically interconnected. For an economic historian such as North, institutions are primarily to be understood in terms of legal frameworks that structure and constrain the actions of individual organizations or bodies such as firms, trade unions, churches, schools or universities: ‘they [organizations] are groups of individuals bound by some common purpose to achieve objectives . . . institutions are the underlying rules of the game and the focus on organisations (and their entrepreneurs) is primarily on their role as agents of institutional change’.45 Looking at this distinction we would be more inclined to subsume theatre under the category of organization or body. This certainly pertains to individual theatres. Even an ‘institution’ such as the National Theatre in London is an organization in the sense of being a ‘group of individuals bound by some common purpose’. However, at another level it is also part of an institutional framework or environment determined by an Act of Parliament and sustained financially, among other sources, by the Arts Council. Within this institutional environment it is interrelated with other institutions including government policies regarding the performance of the arts in a free market economy.46

If we turn now to the field of theatre and, more broadly, art (which is not to say that the two are coterminous), we can usefully maintain the distinction between institutions on the one hand and specific organizations or bodies on the other. Theorists of the avant-garde such as Peter and Christa Bürger differentiate quite emphatically between ‘institutions of ART and social organisations such as publishers, bookstores, theatres, or museums which mediate between individual works and the public’.47 In this distinction the institution of art is located on a higher level of abstraction and it is directly linked to ideas and beliefs pertaining to art’s function in society: ‘those notions about art (its functional determinants) which are generally valid in a society (or in individual classes or ranks)’.48 The central functional determinant for art’s institutional legitimacy is the autonomous status it has come to assume in bourgeois society. This is the result of a historical process that begins in the eighteenth century and which now determines the way modern societies perceive art and its function. Although its origins clearly lie in eighteenth-century Europe (and perhaps even earlier) this institutional model, with some local variations, can now be found throughout the world. Such a definition shifts our understanding of institutions away from a quotidian association with stasis and mechanistic bureaucracy (although the latter are not unknown in arts-related organizations) and locates it instead in the sphere of beliefs, ideas and norms. In this respect the Bürgers’ abstract definition comes close to neo-institutional theory with its emphasis on cognitive patterns and more generally the importance of ideas in the construction and sustainment of institutions.

With the distinction between institutions understood as ‘epochal functional determinants’ within a society and specific organizational forms we can look now more precisely at the institutional dimensions of theatre. As Loren Kruger argues in her study of the national theatre movements in England, France and the USA, the institution of theatre must be understood as an intersection of political, economic and aesthetic spheres: ‘a comprehensive theory of the institution of theatre cannot ignore the continued dialectic between economic and political constraints and aesthetic norms governing theatre practice, as well as the discourses that may represent one as the other’.49 While the present book does not purport to provide such ‘comprehensive theory’, it does argue that an investigation of the theatrical public sphere needs to take special cognizance of theatre’s institutional place in a society. As theatre moves from being a loosely structured organization to a fully-fledged institution, especially one enjoying public subsidy, so too does its function as a generator of and interlocutor in the public sphere change. As institutions, theatres sustain a public sphere of debate that goes beyond particular productions and performances. The appointment of artistic directors and questions of governance and funding attract today vigorous comment by those who may not even actually go to the theatre but who participate none the less in the various forums available. Theatre’s very institutionalized status can engender a vigorous public sphere because it is part of the cultural body politic of a community.50

How then can we reconcile the different notions of a theatrical public sphere outlined so far? The performance of passionate protest and the longue durée of institutional structures, agonistic affect and rational debate? Must they necessarily be seen as irreconcilable opposites? I have argued that agonistic passions and ludic critique can be integrated into the theatrical sphere without forfeiting theatre’s place as a forum for debate. By the same token, the argument can be and has been made that the stage itself can be regarded as a kind of ‘virtual’ public sphere. In her study of national theatres of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Loren Kruger develops a concept of the public sphere that mediates between the fictional issues presented onstage and the wider political and social debates engendered and represented by an institution such as a national theatre:

The relative autonomy of art and especially of performance by virtue of its symbolic character and its effective distance from general production inhabits a liminal space. Because it is not fully under the sway of the ruling order of things, this liminal space may represent the site at least of a virtual public sphere, in which the very symbolic character of the representation enables the entertainment of alternative social and political as well as cultural experience critically different from subordination to hegemony.51

The semiotics of performance do indeed place a special frame around anything said or done onstage. The liminal space created by performance means that any public sphere engendered is subject to particular rules and understandings. Whether one terms these ‘liminal’ or ‘virtual’ is a moot point. It is however easy to agree with Kruger that the public sphere created in the theatre by performance is of a different order from that outside in the world of ‘general production’ and the ‘ruling order of things’. It is, following Raymond Williams, ‘a site and discourse of subjunctive action’.52 Yet a concept such as virtuality or ‘subjunctive action’ means that we need to bracket off anything enacted within it. For this reason the stories enacted onstage are themselves of less intrinsic interest when defining a concept such as the theatrical public sphere, whether on a historical or theoretical level. As we shall see in the following chapters, while what happens onstage can of course be directly pertinent to studying the theatrical public sphere, it is by no means coterminous with it: our focus, therefore, must be wider. To study the theatrical public sphere we must negotiate the shifting boundaries between the private and the public, between the inside and the outside, between censorship and artistic freedom, between audiences at a performance and publics, who never venture anywhere near a theatre.

1 Johnson (Reference Johnson1820), 162.

2 Habermas (Reference Habermas2005), 15; my translation.

3 Habermas (Reference Habermas, Burger and Lawrence1989), 29.

4 Sennett (Reference Sennett1977), 91. Despite much criticism that has been levelled at the somewhat dichotomous distinction between the private and the public, recent gender-oriented research has begun to reassess its usefulness. In her study of women and theatre in Georgian London Gillian Russell argues that from a social–historical point of view it is necessary to historicize the very distinction between private and public in the eighteenth century, which differs in many respects from contemporary understandings. The distinction between home (private women) and not-home (public men) does not correspond for example with the semantics of private and public, as people at home, both men and women, were not necessarily in private (Reference Russell2007, 8).

5 Salvatore (Reference Salvatore2007), 252.

6 Held (Reference Held2006), 283.

7 Weintraub (Reference Weintraub, Weintraub and Kumar1997), 2.

8 Warner analyses the extremely complex semantics underlying the distinction between private and public by proposing a list of fifteen pairs of contrasting meanings plus three senses of private without a corresponding meaning of public (Reference Warner2002), 30–1.

9 Crary (Reference Crary1999).

10 See States (Reference States1985). The inexorable return of animals and children to the stage in the context of postdramatic theatre signals a clear rejection of the phenomenological and semiotic premises of modernist model. See Ridout (Reference Ridout2006).

11 Habermas (Reference Habermas, Burger and Lawrence1989), 3.

12 Habermas (Reference Habermas, Burger and Lawrence1989), 4. In this characterization, Habermas follows closely Hannah Arendt’sThe Human Condition (Reference Arendt1958), 12–13 and 24–5.

13 Turner (Reference Turner1982), 80.

14 See Rehm (Reference Rehm, McDonald and Walton2007), 185.

15 Ibid., 189, emphasis added.

16 Goldhill (Reference Goldhill and Easterling1997), 54.

17 Mouffe (Reference Mouffe2007), 4–5. This essay has been republished in an extended form in Mouffe (Reference Mouffe2013).

18 Raalte (Reference Raalte, Sluiter and Rosen2004), 279. The whole complex of isêgoria and parrhêsia is thoroughly treated in Sluiter and Rosen (Reference Sluiter and Rosen2004).

19 Foucault (Reference Foucault and Pearson1999a), n.p.

20 Foucault (Reference Foucault and Pearson1999b), n.p.

21 Aristophanes (Reference Aristophanes and Hadas1984), 34, emphasis added.

22 Radin (Reference Radin1927), 223–4.

23 See Cole (Reference Cole2010).

24 Kentridge (Reference Kentridge and Taylor1998), viii.

26 Hayner (Reference Hayner1994), 607.

27 Maslan (Reference Maslan2005), 31. On Rousseau and the public sphere, see also Primavesi (Reference Primavesi, Fischer-Lichte and Wihstutz2013).

28 Tilly (Reference Tilly2008).

29 This is also the origin of the term ‘Protestant’ as those who publicly declared their dissent towards the Roman Catholic Church.

30 The OED cites 1852 as the first usage in the modern sense of ‘protest meetings’ (Oxford English Dictionary online version).

31 See Baer (Reference Baer1992).

32 ‘All artworks – and art altogether – are enigmas’ (Adorno (Reference Adorno and Hullot-Kantor1997), 160).

33 Boal (Reference Boal1985), 139–47.

34 Abrams (Reference Abrams and Spencer2012), 40.

35 www.vpro.nl/programma/ram/afleveringen/17018915/items/17716422/. Last accessed 24 January 2013. Interview on 30 May 2004.

36 See for example Beyerler and Kriesl (Reference Beyeler and Kriesi2005) and Wiegmink (Reference Wiegmink2011).

37 Román (Reference Román2005), 246.

38 Carlson (Reference Carlson2004).

39 Elam (Reference Elam2003), vii.

40 Spencer (Reference Spencer and Spencer2012), 3.

41 Habermas (Reference Habermas and McCarthy1987), 319.

42 Notable exceptions include work on the national theatre idea, which bridges the gap between a history of ideas and specific institutional histories. For the former, see Kruger (Reference Kruger1992); for a combination of the former and the latter, see Wilmer (Reference Wilmer2004).

43 North (Reference North1990), 3.

44 Dimaggio and Powell (Reference DiMaggio, Powell, DiMaggio and Powell1991), 15.

45 North (Reference North1990), 5. North’s strict distinction between institutions and organizations is linked to a specific project of analysing the importance of institutional frameworks for economic performance in particular differential economic growth in different societies and historical epochs.

46 On the link between institutional change and economics in British theatre, see Kershaw (Reference Kershaw1999).

47 Bürger and Bürger (Reference Bürger, Bürger and Kruger1992), 5.

48 Ibid.

49 Kruger (Reference Kruger1992), 13.

50 An example of such institutionally motivated debate is the controversy surrounding the so-called ‘Culture Wars’ in the US in the late 1980s, which represent, according to David Román, ‘the last time that theatre and performance found themselves at the heart of national debate’ (Reference Román2005, 237).

51 Kruger (Reference Kruger1992), 17.

52 Ibid., 56.