I don’t know if we felt liberated but we would even joke during work hours, we were happy. Was it the union support or were we just tired of being in that position? Things changed. We would not get scolded or threatened to have our daily wage taken away from us for talking. We felt free!

He helped me to build my union hall, he learned me how to talk.

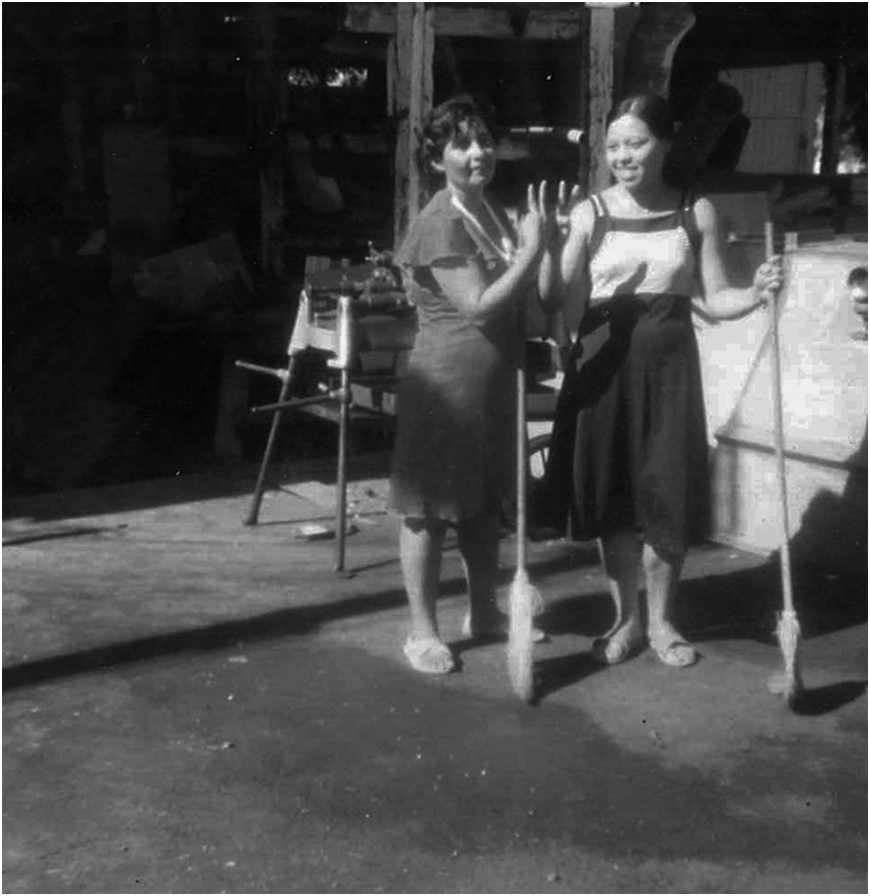

Gloria García was born and raised in a tiny seashore village on El Salvador’s eastern coast.Footnote 1 When she was 10, her father brought her and two sisters to Puerto El Triunfo. She immediately started work on a nearby cotton hacienda. She planted, pruned, and picked cotton for 25 cents a day. She recalls the unrelenting sun, the exhaustion, the prohibition against play, and her infected hands. Gloria’s father found work at the shrimp processing plant Pezca S.A. Her older sister also got a job there peeling chacalín (sea bob). Even though they paid little rent for their mangrove bark dwelling, they were barely making ends meet. Her dad eventually got Gloria a job in the plant, but they had to change her birth certificate so she appeared to be 14 instead of 12. The foreman complained that she was so skinny that she looked like she was nine. And the work was hard at first. After a day’s labor, her hands were cut, raw, and infected but it was better paid and less onerous work than on the cotton hacienda. She got to play on the Pezca baseball team against the other plants, Atarraya and Mariscos de El Salvador. She also went to night school the rest of the year and finished the sixth grade. Despite doing well at school, her work schedule was too intense and unpredictable to continue her education.

Over the next several years, Gloria became increasingly adept at peeling and eventually she gained a permanent position so that she wasn’t laid off at the end of the chacalín season like 40 percent of the labor force. She also got shifted around to various assignments, alleviating the boredom and allowing her to meet new people among the plant’s labor force of more than 500 workers. By the time Gloria was 18 in 1971, she had become accustomed to life and work in the plant and no longer suffered as much from pain and exhaustion. She was able to enjoy a minimum of leisure – occasionally taking the bus 10 miles with her friends to Usulután to the cinema. Sometimes on Fridays she could buy some clothes and makeup from the open market outside of the plant. Almost all her earnings, 18 colones (US$1.00 = 2.5 colones) a week, however, she turned over to her father.

As we shall see, Gloria’s frustration with managerial authoritarianism, low wages, and poor working conditions eventually led her to union activism. Her union participation marked her life dramatically. Her husband opposed her leadership role and left her to raise her two children as a single mother. In 1981, death squad threats and violence drove her into exile.

With the exception of her brush with death squads, Gloria’s experiences typified those of her fellow rural migrants to Puerto El Triunfo. Gloria and many of her female coworkers, over the course of but a few years, became active in a burgeoning union movement in the port allied with a left-wing labor federation. Their gendered experiences of mobilization, the main subject of this chapter, reflect the process of labor activism and radicalization of the Salvadoran worker and peasant movements whose militancy and courage in the face of violent repression received global attention. There are salient differences, however, to the local story. Most scholars argue that labor and peasant radicalization was a direct response to state repression.Footnote 2 Although in November 1977, the National Guard arrested four union leaders and held them for a couple of days, until 1980, there was virtually no other consequential anti-labor repression in the port. The transformation of the Sindicato de la Industria Pesquera (SIP) from a company union, tied to the pro-regime labor federation, into an integral part of a radicalized national labor movement was a largely endogenous process and not a response to state repression. Women’s struggles for full rights for seasonal workers (almost all female), for their own specific needs, and for dignity in the work place decisively shaped that process.

Yet the transformation of labor that challenged the shrimp companies and their oligarchic owners was a fraught, contentious, and incomplete process. The insurgent union leadership had to confront three major obstacles. First, the union had to challenge and at least neutralize the political conservatism of the majority of the workforce. Second, SIP activists had to overcome the ideological consequences of a highly gendered division of labor that marked the private and public lives of female workers and their accompanying apathy.

Female workers, the majority of the labor force, were vital to the union’s success. Their activism commenced along with a conscious effort to publicly voice their concerns and to overcome internal divisions. The male leadership also had to overcome their biases as women pushed hard to make their concerns those of the union. Third, the union leadership had to deal with the machista lifestyle and ethic of most of the fishermen and their opposition to the militancy of the insurgent SIP leadership. That opposition during the 1970s derived primarily from the pro-company orientation of Sindicato Agua. Moreover, their unique form of resistance to the companies by the 1980s would have an acutely negative impact on the plant workers.

In October 1971, Gloria witnessed the arrival in port of the 39 fishing boats administered by companies tied to Pezca S.A. There was a ceremony in which the captains and fishermen renounced their membership in the SIP and the union leader accepted their resignation. They then founded their own union that locally would be called SGTIPAC.Footnote 3 Many fishermen and plant workers believed that the general manager of Pezca, Francisco Varela, had engineered the whole operation on the basis of his friendship with a group of captains. He cajoled the captains into believing that they would receive special treatment from the company unavailable to them as members of SIP. That founding moment of labor/management complicity would condition their harmonious relations with the company until 1979. During that period, they never supported SIP job actions. At the founding of Sindicato Agua, there were no salient ideological differences between the unions, but that would change over the course of the decade as the SIP leadership began to work with the Federación Nacional Sindical de Trabajadores Salvadoreños (FENASTRAS), an independent, Left-oriented labor federation.

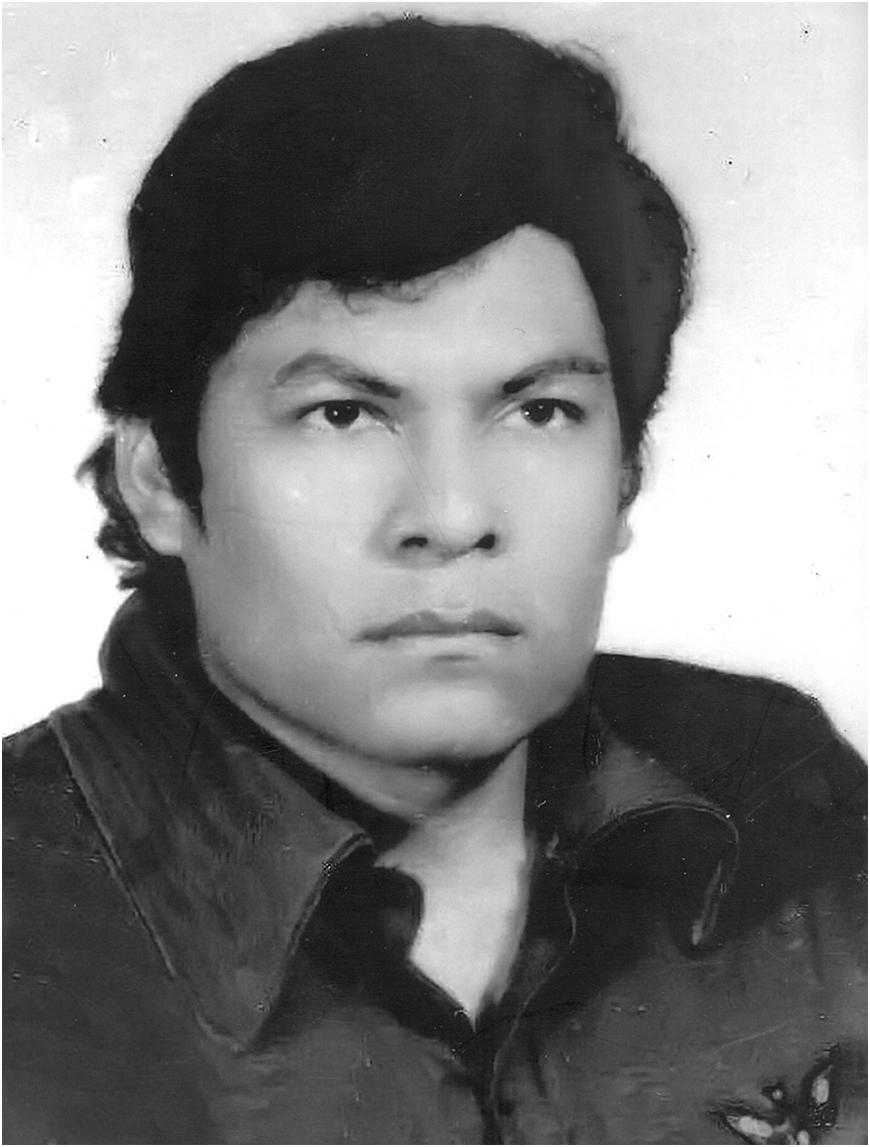

Figure 1.1 Pezca S.A. workers in 1970s

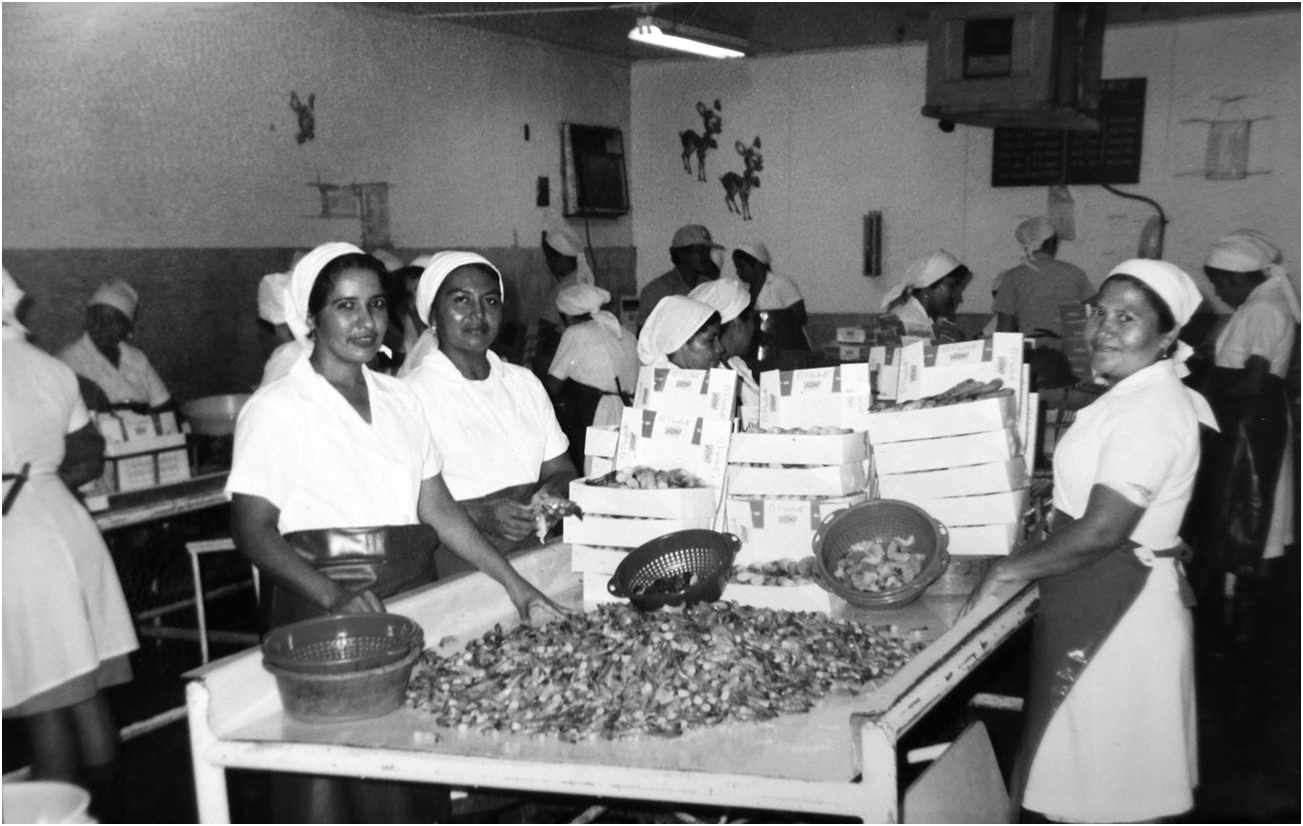

Throughout the remainder of 1971, the company took the offensive against SIP. Pezca refused to make any concessions during the contract negotiations. In December 1971, the union launched the first strike in the history of the company. At the same time, workers at Atarraya S.A., the second-largest processing plant, launched another strike; most of the port was paralyzed. The Pezca-affiliated fishermen in Sindicato Agua continued to work, significantly weakening the position of the plant workers. Their strike funds dwindled as SIP General (the district union) had to support the Atarraya workers as well. Both groups suffered through a Christmas with no money to buy toys for their children. The SIP general secretary, Manuel Muñoz, supported by others in the leadership, then pushed the rank and file to accept the deal that Pezca was offering. The company offered raises of only 5 centavos (US$0.02) a day for permanent workers and 3 centavos a day for eventuales (seasonal workers). The deal seemed laughable, but Muñoz, a respected leader and highly skilled carpenter, staked his reputation on it and most of the unionized workers saw no alternative. Almost immediately though, rumors swirled around the plant, suggesting that Muñoz had been paid off. To this day, Gloria believes that the raise was really 1 colon 3 centavos and that he pocketed the rest.

Regardless of the truth of the matter, Gloria and her friends were furious at the union leaders, the company, and the strikebreakers. She resolved to get more involved in the union. Up until then, she had belonged to the union but did not attend meetings and did not follow events closely; nor did most of the other young female workers. Gloria approached Noé Quinteros, 23, who had served on the strike committee and had seen close up what he also read as corruption. He was an eventual (seasonal worker) who also worked in the cold storage section in Planta II where they processed chacalín. Originally from the countryside in the remote, northeastern department of Morazán, Noé had arrived in the port in 1966 at the age of 18, when his father found work as a foreman on a nearby cotton plantation. He got work as an eventual in cold storage during the chacalín season. When the season was over, he worked as an extra on fishing boats, where his main job was to cut off the heads of thousands of shrimp a day. That experience soured him on life at sea. His brother also worked at Pezca and yet the family income was barely enough to sustain the family of nine. Enraged with the union leadership, Noé looked around for other allies. He saw that the Atarraya strike had worked out much more favorably for the approximately 200 workers. He approached one of their leaders, Evelio Ortiz Palma.

Ortiz Palma was a key union leader in Atarraya. He was a carpenter in the varadero (boat maintenance and repair area) section of the plant, made up primarily of skilled workers. That group formed most of the leadership of the Atarraya Local. Previously, he had owned a small carpentry shop in the nearby town of Jiquilisco. When the shrimp industry opened up, he hired on as a fisherman, attracted by the possibility of high wages. As a young man, he enjoyed the work and kept at it for two years, but when the captain recognized his carpentry skill, he was given a job at a boat repair facility.

For the next six years, Evelio worked as a carpenter in the maintenance facility five miles from Puerto El Triunfo on the other side of the Bay of Jiquilisco. There, he enjoyed a fair degree of work autonomy and got along well with the Dutch owner and management. When Atarraya absorbed the small shipyard, he moved to Puerto El Triunfo. He married a plant worker and moved out of the plant barracks and into a small house made of mangle (mangrove). They managed to get by. Shortly after the war with Honduras (the so-called Soccer War of 1969), Atarraya brought in José Noltenius as the new plant manager. Noltenius was from an elite background and introduced a new level of authoritarianism into management-labor relations in the plant. His different accent, intonation, and mannerisms caused Evelio and his workmates to believe that Noltenius was a Honduran. The new manager wanted to bring in his own workers, perhaps Salvadoran refugees from Honduras. In the war hysteria of the moment, it was easy to conflate the war with Noltenius and the anger and anxiety he caused in the plant.

Although a union existed in the plant, Evelio only began to become involved with the arrival of Noltenius. In 1970, Evelio helped spearhead a work stoppage that reinstated the workers who had been displaced by the arrival of the new manager and his crew. That year the membership elected him to the Junta Directiva of the Atarraya Local, and he “took the work real seriously.”Footnote 4 During the fall of 1971, Evelio, along with the Local leadership, initiated contract negotiations with the company. Around this time, they began to hear growing complaints from female workers.

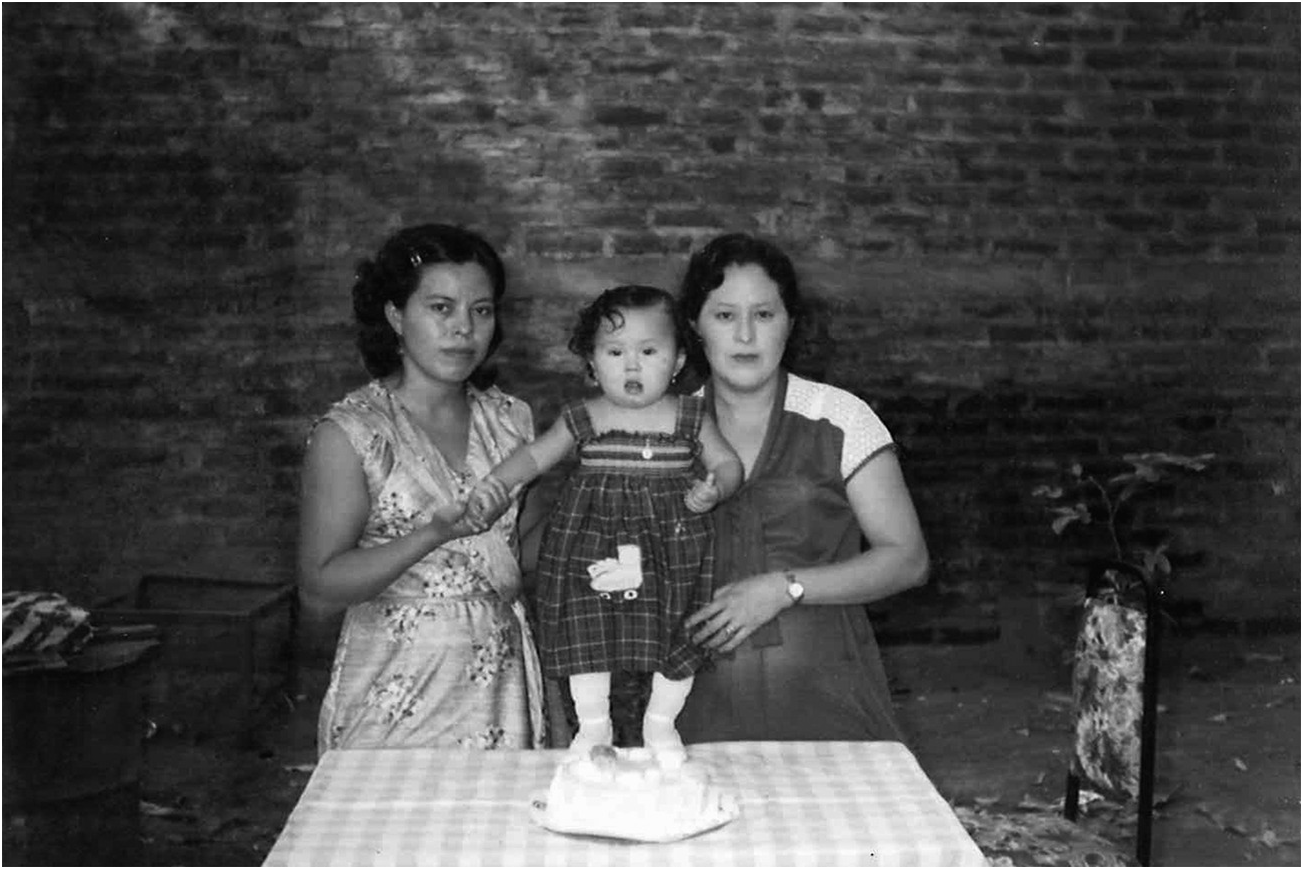

The women had many grievances against the jefe de personal, Rafael Villatoro. He was taking young women out of the plant and having them work as domestic servants at his home over the weekends. Even worse, he was abusing them sexually. Atarraya workers’ anger heightened even more as the company fired six union activists and used stalling tactics in contract negotiations. In December, the Atarraya Local launched a strike for increased wages and for an end to sexual harassment. The company used strikebreakers including fishermen but also employed other workers from the outside. One worker recalls Christmas that year:

We spent Christmas lulling our kids to sleep with no toys. The babies screamed but we had nothing to give them not even cold tortillas, just sugar water. All this while the radio blares FELIZ NAVIDAD. … the bosses’ servants walked by with their enormous gifts that they had gotten for their servility … and we got to savor our kids with distended stomachs and the sadness of life.Footnote 5

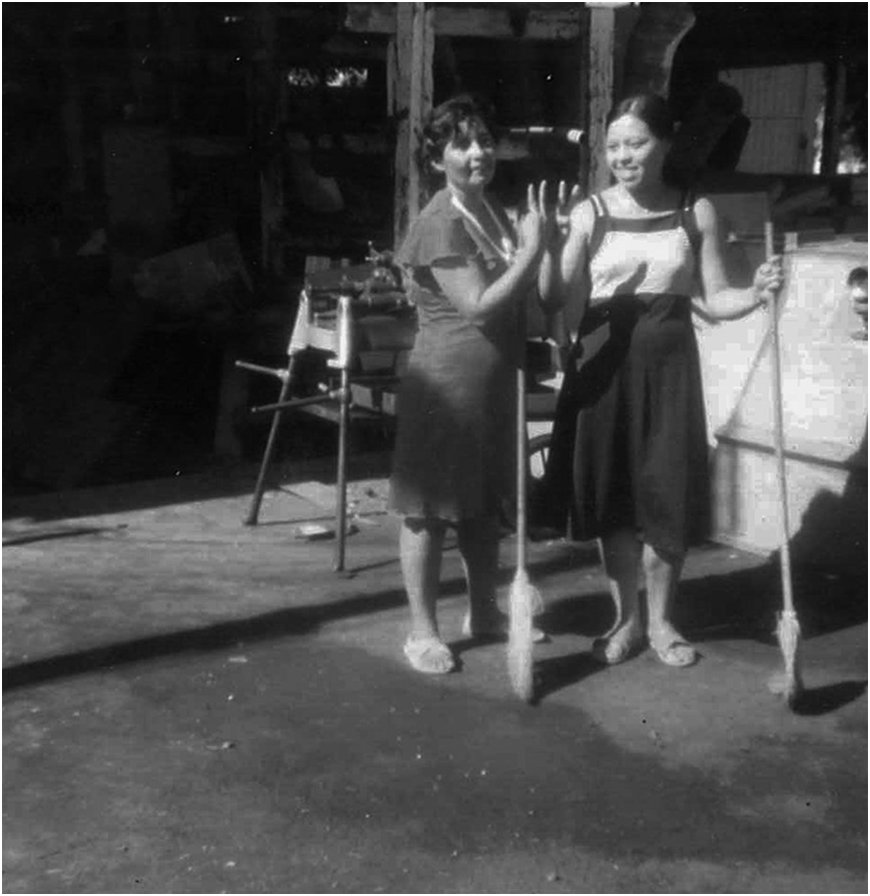

Figure 1.2 Women working in Atarraya S.A. in late 1960s or early 1970s

Despite the extreme and painful adversity, the unionized workers held on for 31 days until Atarraya ceded ground.Footnote 6

On January 21, 1972, SIP reached an agreement with management. The company resisted on the key issue of pay during the strike but promised to give jobs back to the six workers who had been fired for union activities and not to take reprisals against the “agitators.” Moreover, they agreed to remove the strikebreakers from the labor force. They offered raises that amounted to 68 centavos a day, or roughly a 20 percent increase. The company also granted the key demand to retire Villatoro because of the charges of sexual harassment.Footnote 7 Following the strike, female membership in the union soared, representing nearly 80 percent of total affiliates, far greater than their proportion in the workforce.Footnote 8

Figure 1.3 Female workers in Atarraya S.A. in late 1960s or early 1970s

Evelio had sat at the negotiating table with a younger union activist, Alejandro Molina Lara, age 28, who, at the time was second secretary of conflicts of SIP General. Molina Lara was a rising star, due to his rhetorical and negotiating skills and his courage. Originally from Usulután, the departmental capital, Alejandro Molina Lara was 22 in 1966 when he arrived in Puerto El Triunfo on a contract assignment to do some welding on a refrigeration tank. A foreman at Mariscos de El Salvador was impressed with his work and immediately offered him a job. Accustomed to the insecurity that plagued artisanal labor, the prospect of a reasonably well-paying steady job appealed to Alejandro. The port, though, was not a major attraction. Recall its nickname, Puerto El Tufo (Port Stink), as virtually no public sanitation existed outside of the packing plants. Most residents depended on public outhouses and many used the bordering mangrove swamps as toilets. Like many port laborers, Molina Lara commuted to work.

He thoroughly enjoyed his work as a welder on the docks; he was good at the job and management and the other workers treated him well. During his lunch break down by the loading dock, he would hang out with a panguero (who captained small boats between the dock and the shrimp boats). The panguero was a SIP activist. Although they maintained friendly conversations, Alejandro did not see the relevance of the union to his particular situation. Nevertheless, he did recognize the egregious situation of the majority of female packinghouse workers who lacked permanent status and any associated benefits; the company also denied them overtime payment. Despite his lack of interest in the union, company foremen observed those conversations with apprehension. Soon they began to threaten him with the loss of his job. Molina Lara knew that four years earlier, Mariscos de El Salvador had crushed the union. Although the union had legal standing, it had virtually no bargaining power. The harassment drove home to Alejandro the unequal power relations and reinforced in him elementary notions of social justice. In addition, he recognized that a position in the SIP leadership would offer him job security.Footnote 9 In 1968, he both joined the union and became a candidate for office. Presumably based on his rhetorical skills and charisma, he won election to the leadership of the Mariscos de El Salvador Local. No one could have realized at the time that he possessed rare leadership gifts that he immediately put to work successfully winning a contract negotiation.Footnote 10

Over the next few years, Alejandro helped spur an organizing drive, among the young female workers, the peladoras and empacadoras.Footnote 11 Women formed the majority of plant employees and thus necessary to any serious union mobilization. In 1970, 38 female workers in Mariscos joined the union.Footnote 12 This influx of young female workers doubled the size of the Mariscos Local. By 1972, virtually the entire workforce belonged to the union. Like Gloria, most of the young female workers hailed from large, deeply impoverished families in the countryside. For those who had started work in the 1960s and early 1970s, their experience, at first, was quite gratifying. They received their first pay, however small, and were able to purchase basic consumer goods about which they had previously only dreamed. The transition to industrial time was not easy and the labor along the conveyor belt was physically demanding – they were on their feet all day – and highly regimented. As they matured into adulthood, the young women came to resent numerous problems ranging from the degrading hiring practices to the working conditions that ruined their clothes and caused their feet to swell (they often had to work in water). They resented their hunger pains toward the end of the eight-hour shift, the lack of breaks, and the yawning pay differential with male workers.

Figure 1.4 Alejandro Molina Lara

Molina Lara met constantly with the new female workers, demonstrating a concern for their everyday problems, vowing to fight on their behalf. At the same time, he began to work with Noé Quinteros and Leonel Chávez, another Pezca worker, equally disaffected from the union leadership since the end of the disastrous 33-day strike in Pezca. They all agreed that the leadership either had sold out the strike or simply lacked the will and fortitude to keep the fight going. Within a year, the three activists won election to the key posts of SIP General.Footnote 13 Their prestige was not based on their job hierarchy as only Molina Lara was a skilled worker. Rather people admired their negotiating skill and their combative, optimistic spirit. As a direct result, increasing numbers of women joined the union and began to participate in meetings. Between 1968 and 1973, the attendance at SIP General meetings rose from an average of less than 200 to more than 500.

Insurgent Leadership

The new union leadership operated on somewhat favorable ground. Labor unions occupied an important space in authoritarian El Salvador. Labor protections, including the right to strike, were enshrined in the nation’s constitution. Nevertheless, unionized workers represented only some 5 percent of the economically active population during the 1970s, in part a reflection of the prohibition against labor organizing among rural workers and the size of the informal labor sector.Footnote 14 Unions did, however, legitimize the military regime specifically through the operation of a pro-government labor federation. Toward the end of the decade, union legality could also be used as an argument to answer Carter administration demands for democratization. Yet the military regime depended upon an alliance with various sectors of the oligarchy, which included industrial capital. The tension between the regime’s discursive support for union activity and its strategic alliance with business interests provided labor militants with a potent rhetorical weapon within their unions and in the broader society. Although management throughout the country often successfully resisted unions, militants could avail themselves of legal standing, however limited.

Despite the advantages of belonging to the pro-regime labor federation, in particular an open door at the Labor Ministry, Leonel Chávez, Alejandro, and Noé engineered the disaffiliation of SIP from the regime-dominated Confederación General de Sindicatos (CGS). At the 1972 congress, SIP militants joined 17 other unions in staging a walkout. The SIP militants promoted this action because they associated the CGS who advised Muñoz with the sellout of the Pezca strike.

The act of disaffiliation did not immediately represent the beginning of a political radicalization process. At that very moment, Alejandro was a councilman in Puerto El Triunfo as a member of the Partido de Conciliación Nacional (PCN), the party of the military regime. Believing he could improve the living conditions in the port, he had agreed to join the PCN ticket in the national and local elections of 1972, widely condemned as fraudulent. Although he was able to push through a major increase in the municipal tax paid by the shrimp companies, Alejandro quickly became disillusioned with the mayor and the PCN, whom he came to view as corrupt. Within a year, he resigned his position and recognized that the corruption of the PCN was tied to that of the regime-controlled CGS.Footnote 15

In the February 1973 union elections, Leonel Chávez won the post of Secretary General; Noé Quinteros became Secretary of Organization; and Molina Lara became the first Secretary of Conflicts. That same year Molina Lara pushed for a new contract at Mariscos de El Salvador so that its salary structure would match that of the other companies. He pursued a strategy that he would follow throughout much of the decade: Following the company rejection of the union demands, he attended Local meetings where he painstakingly presented statistics about productivity, world prices, and inflation to educate the workers about the necessity and potential limits to wage increases. Notwithstanding his efforts, Mariscos de El Salvador responded by laying off nearly its entire workforce.

Probably due to a loss of prestige caused by SIP’s failure to halt the layoffs in February 1974, Molina Lara lost the elections for secretary general to Evelio Ortiz by a vote of 260–190 with another 90 votes going to the former secretary general, Mercedes Muñoz.Footnote 16 Evelio Ortiz always maintained a degree of neutrality between the two main factions of the union, those aligned with Alejandro, Leonel, and Noé and those with Muñoz. He sympathized more with the insurgent faction but maintained a strong friendship with Muñoz. Although the image of Muñoz had been tarnished by the accusations of selling out the Pezca strike, he still maintained a base of support due to his affable personality, his reputation as a highly skilled worker (reputedly the best carpenter in the port) and to some degree to his rhetoric of worker-management harmony. Molina Lara only won election to Second Secretary of Conflicts.Footnote 17

The First Legal Strike in History

Operating from his relatively lowly position in the union hierarchy, Molina Lara led two initiatives. First, he pushed hard to block the introduction of deveining machinery in Atarraya, used for small shrimp and chacalines (sea bob). According to the SIP leader, the machinery had cost more than 200 jobs in Pezca S.A. He unsuccessfully argued that the machines were grossly inefficient.Footnote 18

Alejandro was far more successful in a new round with Mariscos de El Salvador, where he faced Rafael Guirola, a powerful oligarch. Among the four wealthiest in the country, Guirola’s family owned 52 coffee plantations and businesses worth approximately US$50 million.Footnote 19 Guirola rarely negotiated directly with the union but when he did so he remained diplomatic. He shared some other traditional oligarchical values, in particular the right to oblige subalterns to participate in the “don’s” rituals. His workers had to revere his patron saint, San Rafael on May 23; he paid workers double time if they worked on that sacred day. Similarly, Guirola named a sister shrimp processing plant, Pesquera San Rafael. Located in the port of La Unión, the plant processed shrimp during strikes in Puerto El Triunfo.

In March 1974, Mariscos de El Salvador responded to union demands for a contract renegotiation with the firing of 91 female production workers. Molina Lara mobilized his union base to stage protests and work stoppages and also denounced the move at the Ministry of Labor. Guirola did not respond to the ministry’s call for a meeting. From March until June, Molina Lara and Guirola parried continually. The company refused to take back all the workers and, in response, the union staged walkouts. Meanwhile, the SIP General offered significant monetary support to the fired workers. Indeed, in a telling sign of solidarity, workers in the other plants donated a day’s pay to help out the Mariscos workers.Footnote 20 On May 9, Molina Lara stated to the assembly of SIP workers: “The problem with this company is getting worse each day and now we have broken direct relations and have moved on to the conciliation stage.”Footnote 21

Molina Lara navigated the line between direct action and a scrupulous accordance with the Labor Code. Despite the selective work stoppages to protest the mass layoffs, Molina Lara followed each of the strike procedures outlined in the Labor Code: consecutive stages of negotiation, conciliation, and arbitration. Only after following all these stages could a strike be legally declared. A majority of the employees had to belong to the union and a majority had to vote for the strike. Guirola followed the practice of other employers by firing union activists so that fewer than 50 percent of the employees would vote for the strike, thus making it illegal.

At 4:00 PM on June 11, the Mariscos de El Salvador workers walked off the job, declaring a strike against contract violations and most specifically against the firings that they deemed part of an anti-union strategy. Within two weeks, the Juzgado Segundo de Primera Instancia de Usulután (a departmental court that dealt with labor issues) declared the Mariscos strike to be legal, the first such ruling in the history of the Salvadoran labor movement. This remarkable achievement was due in no small part to Molina Lara’s tactical brilliance, leading work stoppages, mobilizing broader support, while rigorously following every step specified in the Labor Code. Guirola’s arrogance surely was a major factor in the court decision. He simply refused to respond to the Labor Ministry at several key moments over the previous three months. Perhaps there was a political dimension as well. The military regime’s legitimacy was at a low point following the well-publicized electoral fraud of 1972. In addition, bowing to the concerns of the agrarian elite, the regime had expelled AIFLD in 1973, due to its promotion of a mild land reform program through its support for the centrist Unión Comunal Salvadoreña.Footnote 22 That expulsion drew protests from the US government and sectors of the international labor movement.

Regardless of the precise motives, the declaration of the strike’s legality proved an enormous boon to SIP. The right to strike was enshrined as an article of the Salvadoran constitution, and the Labor Code essentially placed the weight of the government on the side of the (legally) striking union, forbidding the use of strikebreakers and compelling the company to pay wages during the strike. Following the dictates of the code, the Labor Ministry ordered the National Guard to ensure that there would be no strikebreaking and ordered Guirola to pay wages during the strike and prohibited him from sending shrimp to his facility at La Unión.Footnote 23 The National Guard did not, however, carry out the orders, and Guirola managed to ship shrimp to his plant in La Unión before the labor inspectors arrived. Notwithstanding, Mariscos could only find a handful of strikebreakers (including among fishermen) and thus could not effectively operate during the strike. Rather than negotiate, let alone pay wages, Guirola unsuccessfully appealed the decision to the Supreme Court. His refusal to negotiate galvanized more gestures of solidarity from other unions in the port and elsewhere. After three months, Guirola bowed to the key demand to reinstate and provide back pay (before and during the strike) to all the fired workers. The back and strike pay also covered the losses of fishermen who could not deliver the product. Other concessions included vacation and scholarships for children and the promise not to send shrimp caught by fishermen who worked for Mariscos de El Salvador to the San Rafael facility.Footnote 24

This was a dramatic victory, one in which all SIP members could take pride: They had contributed generously to the strike fund.Footnote 25 The union leadership was so pleased that they contributed more than US$400 to throw a victory celebration.

Molina Lara’s prestige grew significantly as a result of the strike victory. In February 1975, he won the SIP general elections for secretary general, 243–97 besting Evelio Ortiz. This was Alejandro’s third try for the top office in the union. Well before the victory, Alejandro had a revelation:

I realized that I wasn’t at all intimidated by being around management or the company lawyers. I enjoyed being at their level. I was even superior to them because I represented the workers.Footnote 26

Moreover, he had an unflinching goal: to allow the workers of Puerto El Triunfo the possibility to enjoy a dignified life and dignified work. His emotional satisfaction was powerful. He had known psychologically that he was management’s equal for some time, but his experience at the helm of the Mariscos S.A. strike and his humbling of don Rafael Guirola had confirmed his intuition.

During the mid- to late 1970s, the three shrimp companies were highly profitable as the international prices soared higher than US$4.00 a pound and the fishing grounds were plentiful.Footnote 27 Before each contract renewal negotiation, Molina Lara carefully tracked the companies’ profitability and communicated the information to the union membership.Footnote 28 In each union meeting, he laid out the inconsistencies in the company’s argument against wage increases, while highlighting the deeply felt problem of double-digit annual inflation rate during the mid- to late 1970s. When a given company would not yield in one year, they built up their forces for the following year. Thus, in September 1975, Molina Lara reported on the failure of negotiations with the three main companies. Speaking before more than 300 members of the Pezca Local, he commented, “[W]e did the humanly possible but the company exhibited no understanding nor was there enough solidarity from the assembly to support our demands.”Footnote 29 He referred to a lack of unity among the rank and file over exercising a strike threat. Without such a threat, all three companies held their negotiating ground. Mariscos de El Salvador, granted a 6 percent raise to plant workers and 8 percent to fishermen despite an inflation rate of more than 19 percent in 1975.Footnote 30

Despite the setback, SIP continued to pressure the companies. In February 1976, after a 10-hour marathon negotiation session, Pezca conceded a 15 percent raise. Although Molina Lara was not satisfied, the rank and file accepted the raise that, combined with the 1975 raise and the decline in the rate of inflation (7 percent in 1976), in effect maintained their real salaries intact, at a time when the rest of the working class faced declining real wages.Footnote 31

Molina Lara (who won three consecutive elections for secretary-general) and the other union leaders engaged in painstakingly slow organizational work. Gradually, the male leaders were able to incorporate increasing numbers of female workers into the local and district leaderships and they became a more active presence in union meetings. By the end of the decade, more women than men spoke during union meetings. In 1977, SIP again fought for improved contracts in the three companies. Noé Quinteros and Leonel Chávez won office in the Pezca Local, opting to mobilize the rank and file and leave Molina Lara in full command of the SIP General Union. In a highly significant change, women won half of the Pezca Local positions. The combination of experienced leadership and female activists fomented greater militancy in the Local.

In 1977, the Pezca Local launched a drive around demands for improvements in salary and working conditions. In July, the company offered a 1.15 colones a day raise with a fixed two-year contract (typically parts of contracts could be renegotiated every year). Molina Lara spoke to the Local assembly of 173 workers and issued a “llamado a la conciencia” (call to conscience) as Noé called for “unity.” Molina Lara continued to negotiate as the Pezca Local inched toward a strike. On July 21, the entire Pezca workforce walked off the job for the first time since the failed strike of January 1972. This time they won a resounding victory with an immediate wage hike of 1.60 colones per day and a series of other major concessions by the company.Footnote 32 As a result of the strike, SIP workers joined the ranks of the country’s best-paid industrial workers, the majority of whom had seen their real wages decline dramatically over the previous few years.

Due to the perishable nature of the commodity the SIP unions possessed what Beverly Silver calls “workplace bargaining power … that accrues to workers who are enmeshed in tightly integrated production processes, where a localized work stoppage in a key node can cause disruptions on a much wider scale than the stoppage itself.”Footnote 33 Following Charles Bergquist, this power increases substantially when the industry is a key source of foreign exchange (shrimp ranked as the third-highest source in the 1970s).Footnote 34 Molina Lara had acute practical knowledge of the commodity chain and the production process. He was able to depend on the union’s overwhelmingly female rank and file to carry out work stoppages (or slowdowns) to respond rapidly to even the most minor problems that developed on the shop floor. Combined with a growing union membership and commitment, that is its “associational power,” SIP had the potential to transform the lives of its members and to carve out a relatively autonomous space of freedom in an authoritarian society.

Politics and Discord

Yet as can be discerned from the llamada de conciencia and the lamentations about the lack of solidarity, the achievement of worker unity was a fraught and incomplete process. The first impediment to unity was political. Throughout 1975, Molina Lara, formerly apolitical, had increasing contact with the independent Left-oriented federation FENASTRAS. In the federation, he began to relate to more experienced union militants, including those who belonged to the Salvadoran Communist Party (PCS) and to the Frente de Acción Popular Unificado (FAPU), a group to the left of the PCS. From both leftist organizations, Molina Lara gained access to people and some limited reading material (pamphlets) that allowed him and his friends to understand the situation of the laboring classes in the country and more specifically the alignment of political and economic forces that SIP needed to confront.Footnote 35 Leonel Chávez joined the PCS, and he frequently engaged with Alejandro in more or less private conversations about politics and labor. Chávez disagreed, at least in practice with Alejandro, Noé, Evelio, and Gloria García for whom it was imperative to keep politics directly out of the union. García recalls how she scolded Leonel Chávez for showing a Soviet film about housing in November 1977: “Aqui se pelea la cuestión laboral” (Here we are fighting about labor issues). He responded that he was showing it “para que se abren los ojos” (to open up eyes). The anti-political position of Gloria and Noé and many others hinged on an understanding that the union represented a rare democratic space but one that the government could easily shut down. Moreover, activists like Gloria and Noé came to believe in a form of militant syndicalism as the best way to achieve more power and improved lives for workers.

At the same time, there was an even more pragmatic side to the anti-political stance because the SIP leadership faced a difficult political reality. Although the opposition Christian Democratic Party (PDC) had strong support in the port, the majority of male workers and many female workers belonged to one of two right-wing parties: the official party the PCN or Partido Popular Salvadoreño.Footnote 36 Moreover, many workers belonged to the rightist, paramilitary group ORDEN (Organización Democrática Nacional). Given the strong pro-regime support from the union membership, SIP’s affiliation with the increasingly Left-leaning FENASTRAS was a source of potential conflict and concern.Footnote 37

This political concern became more palpable as national-level repression became pronounced. National Guard killings of protesting campesinos at Tres Calles in the department of Usulatán (Puerto El Triunfo’s department) and La Cayetana (San Vicente) had galvanized national attention. Similarly, on July 30, 1975 the National Police opened fire and killed at least a dozen protesting university students in San Salvador. On September 26, unknown assailants gunned down a Communist union activist, Rafael Aguiñada Carranza, the head of FUSS (a union federation in which the PCS was strong). Molina Lara joined others in pushing for a national strike of protest. In front of more than 300 SIP members, Leonel Chávez condemned “the constant blows against the labor and peasant movement by the fascists who want to dominate the people.”Footnote 38 Although the national strike initiative did not get off the ground, the SIP leadership did introduce national politics and a left language of denunciation into the union discussions as they attempted to organize the rank and file to participate in the protest.Footnote 39

Eventually, Molina Lara and his group were able to convince the rank and file to support the independent leftist federation on the grounds of its capacity to deliver solidarity when SIP needed it. Similarly, they developed a language of class solidarity phrased as a logical extension of union activity that had been sanctioned by the constitution. In other words, the constitutional acceptance of the right to organize and strike provided a discursive opening toward expanding notions of solidarity.Footnote 40

Molina Lara was careful to cover his right flank. In fact, during most electoral cycles he recruited an ORDEN member to serve on the SIP’s leaderships ticket. He thus co-opted a local branch of an organization that would become the nucleus of right-wing death squads. Molina Lara was able to turn the ORDEN member and many other rightists into good trade unionists in part by guaranteeing that politics would stay out of the unions.

Gendered Division of Labor

The high level of gendered labor segmentation within the three plants was another source of division. Those divisions often translated into sharp differences in perspectives and attitudes toward union organization. Only a minority of workers, both male and female, could count on salary and benefits for the entire year. A substantial sector of female workers, who classified and packed the shrimp were frequently laid off when the supply dwindled. Finally, there was an even larger group of workers who were employed as eventuales (seasonal or occasional workers) who had even less job security.Footnote 41 In the La Ballena processing plant of the Atarraya group, more than 70 percent of the workers were temporary.Footnote 42 In Pezca S.A. most eventuales, some 40 percent of the workforce, labored in Planta II. The permanent workers in Planta I often exhibited a marked degree of superiority toward those of Planta II. One female worker in Planta I recalls that the workers of Planta II were poorer, less educated, more country (“más rústica”), less reliable, and more rebellious.Footnote 43 Planta II women recall being treated with disdain by Planta I female workers. One Planta II who eventually became a SIP leader had to endure the nickname, “letrina” (latrine), a word uttered to her face more often than her name. She was called that because she had lived in a rancho by the public latrines, when private toilets were virtually nonexistent. Her father supplemented the family income by cleaning the latrines, hence her nickname. That level of intra-class derision was hard to overcome, but necessary to forge a united labor force.

In Pezca S.A., the largest and most modernized of the three packinghouses, employing more than 500 workers, Plant II was exclusively devoted to the smallest species of shrimp, chacalín, or sea bob. Previously discarded, the domestic market for chacalín emerged in the late 1960s thanks to the introduction of supermarkets in San Salvador; by the mid-1970s an export market opened as well.Footnote 44 In 1976, a typical voyage would net 2,333 pounds of chacalín and 1,800 pounds of the larger varieties of shrimp. The company paid fishermen 557 colones per ton for white shrimp (it fetched up to US$4.50 per pound in New York) and 191 colones per ton of chacalín.Footnote 45 During the season, from July to November, several hundred female workers peeled each chacalín by hand and then placed it on a conveyor belt that passed over a machine. When the chacalín reached a certain point, a rotating cylinder penetrated it, as a high-pressure stream of water removed the vein and rinsed the product that then dropped onto another conveyor belt. For the smallest of the chacalines, a special “peeling machine” peeled and deveined the product.Footnote 46 Female workers selected the undamaged chacalín and packed them to be frozen and then transported to the airport or to the supermarkets. Men operated all machinery in the plants. The machine operators and maintenance machinists earned as much as 50 percent more than the female workers and occupied the key positions in the union, during the 1970s.

Permanent workers processed the larger shrimp in a less labor-intensive fashion. The shrimp came through a classification machine (rated by the number it would take to make a pound) and then the workers would pick out the nondamaged shrimp to pack into five-pound boxes that would be frozen and stored.

From the companies’ vantage point, eventuales were disposable, interchangeable, and highly exploitable. At the start of the season, a whistle announced the arrival of the fishing boats and hundreds of women would jostle with one another at the plant gates, trying to get hired. The majority who lived in the countryside were at an extreme disadvantage because they had no information on the arrival of the first chacalín boat.Footnote 47 Although they performed more difficult work – as they had to shell each chacalín – the seasonal workers – mostly women – received roughly one-third less pay than did permanent workers who classified and packed the larger shrimp; the eventuales also did not receive overtime pay and did not have health insurance.Footnote 48

From the beginning of their tenure, Alejandro, Noé, Leonel, and others strove to transform the status of the female temporary workers both as an act of fundamental social justice and as a linchpin of a strategy to augment the power of the union. Their earliest focus was on ending the piece rate system and substituting it with hourly pay rates. Female workers overwhelmingly backed this measure. The union won this change in pay structure in each plant during the mid-1970s, thus modifying the work pace for the entire labor force. The SIP leadership also pushed hard against any management employees who behaved hostilely toward union militants. In virtually every job action, one of the demands was for the removal of a supervisor or foreman.

Molina Lara, as noted before, worked to organize the previously unorganized eventuales and to increase female participation in each of the union locals in the port. By 1979, five of the seven officers of the Pezca Local were women. The top posts in SIP General, however, still went to men. The typical explanation by male and female union activists at the time and in memory was that women were more militant and committed than male workers, but that they shied away from occupying leadership positions due to their domestic labor obligations.

In February 1979, a female Atarraya worker commented on the gendered dimension of the labor struggle in Puerto El Triunfo. She argued that the company fired the primarily female temporary workers whom the company treated like “machos de carga,” substituting new ones.

Among us, since we women are the majority in the plants and the authorities beat the men first, and the authorities are always around, in the sessions we women protest first. The men hardly speak out, but when we decide to struggle we form a unified front.Footnote 49

This is a novel enunciation of a position, at once proto-feminist and syndicalist. Echoing a common belief and practice in revolutionary movements, the female activist argues that women are more militant and courageous than men in part because the authorities are more likely to beat males.Footnote 50 Through speaking up, the women attempt to shield the men from physical harm. The statement also suggests the remarkable transformation in consciousness experienced by female workers over the previous decade. From apathetic workers, they are now visibly and vocally in the forefront of the class struggle in the port exemplifying the ideology and practice of solidarity. Female participation in large meetings did increase dramatically over the course of the decade. Whereas mostly male voices were recorded in the minutes earlier in the decade, by 1978, half of the speakers – often in front of more than 500 people – were female. Almost all their declarations encouraged militancy in defense of union demands and worker solidarity within the port and beyond.

The statement by the anonymous female militant also refers to the National Guard mentioned earlier. On November 18, 1977, shortly before the regime declared a state of siege to quell labor, student, and peasant unrest, Leonel Chávez organized the showing of a Soviet documentary. Before the film began, “The authorities arrived in trucks. We had to calm the children who began to cry from fear. We gathered up our courage. Then they entered with bayonets and went straight for the leaders. Everyone hit the floor because we could hear shots … they beat Alejandro so that blood poured from his ears and mouth. We thought they had killed him.”Footnote 51 According to various witnesses, the attackers destroyed as much of the union hall as they could and then carried off Alejandro, Leonel, Delia Cristina Hernández, and two other union leaders.Footnote 52

Immediately afterward, dozens of union members followed the National Guard to the departmental capital. Despite a government claim that the National Guard had uncovered “subversive propaganda,” union protests helped to free the union activists. Upon their return to the port, workers and their families broke out in a spontaneous fiesta. The beating and the repression only enhanced Alejandro’s reputation. As one female union militant commented,

Alejandro is our secretary general of everyone: he is our idol. Because if Alejandro says “I’ll be there” when we get off work at 10 pm he’ll be there … He orients us in our struggles: GO TO PEZCA’S GATE, THOSE WOMEN NEED OUR HELP.

Another female worker even penned a poem:

We of Puerto El Triunfo never have lost a strike; we always struggle together; We don’t let the deceitful bosses offend us, though they try to every day; Alejandro Molina Lara is our leader and he is a precious pearl that we found in the sea; all the workers of the fishing industry will die before they do him harm; we won’t allow his noble principles to fail.Footnote 53

Yet the dynamic between Alejandro and the predominantly female workforce was far more complex than the paean would suggest. Molina Lara and his male compañeros had to undergo a transformation, particularly with regards to their notions of women and femininity. They had to recognize female militant workers as women and not see them as stereotypes framed in derogatory language.Footnote 54 Moreover, they had to begin to treat women as intellectual and moral equals. Gloria García recalls, “Alejandro did improve quite a bit. But you know, in the end he always thought that he knew better.”Footnote 55 García’s statement is an implicit recognition that changes in social attitudes among even the most progressive males involved an incremental process.

Similarly, the insurgent leadership learned from the women very early in the game that they could not countenance any forms of harassment on the part of management; indeed, the Atarraya strike of 1971–72 pointed to the issue as capable of provoking mass mobilization. It is remarkable that women recall less than a handful of incidents of sexual harassment during the entire decade. Although consensual affairs took place among the workforce (and between rank and filers and union leadership), there were few, if any, cases of harassment (e.g., sexual aggression or unwanted advances). Women workers recognize the role of the union in militating against any form of sexual harassment in the plant. This contrasts sharply with the experience of female workers in other parts of Latin America.Footnote 56

During the mid- to late 1970s, as more and more women became active in the union, they began increasingly to attempt to exert informal control over the production process.Footnote 57 In effect, female and male workers neither required nor accepted interference from either the jefes de producción or management. That said, there were numerous minor skirmishes over that control. Mauro Granados, for example, often stood on the other side of a plate glass window to observe the workers. When he saw the women pop a candy in their mouths or engage in conversation among themselves, he would come down to scold them. Such managerial actions annoyed the female workers who, by the late 1970s would retaliate by talking back to their superiors and by calling them out in general assemblies. SIP’s record of ridding the plant of anti-union managers made those employees wary.

The female workers also developed concrete demands that the SIP leadership adopted. They fought for and, by the end of the decade, obtained the construction of a cafeteria. There had been many cases of women fainting on the job because they had to stand six hours without any food and at times eight hours given that the trip home for lunch was almost impossible to pull off within the allotted half an hour break. As Eloisa Segovia put it, “[T]he union gave us a chance to eat.”Footnote 58

That demand accompanied a series of others that if not specifically female in nature, fundamentally benefited that segment of the workforce. For example, they won the right to a first aid center on the premises that treated women who suffered large numbers of cuts from handling the chacalín. Similarly, by the end of the 1970s they had gained the right to four uniforms and three pairs of boots per year. In addition, they achieved the right to two coffee breaks. The union also procured 30 high school scholarships for their children. As part of the contract, they received a right to 5 pounds of shrimp and 10 pounds of fish a month. In the words of Carmen Minero, “Before we worked like burros and could only touch the shrimp, now we could eat it.”Footnote 59 Although these victories seem minor enough, cumulatively they amounted to a significant improvement in their working and home lives. Without the active participation of the female workforce, those demands might not have been even formulated much less achieved. Those victories also empowered and unified female and male workers as they recognized their collective agency in the everyday betterment of their lives and working conditions. The workers came to view the processing plant, if not as a place of joy, at the very least as their own space in which, within generally prescribed limits, they could work at their own pace, in their own way, with a reasonable degree of amusement. On the night shift, they often played games, even spraying each other with hoses.

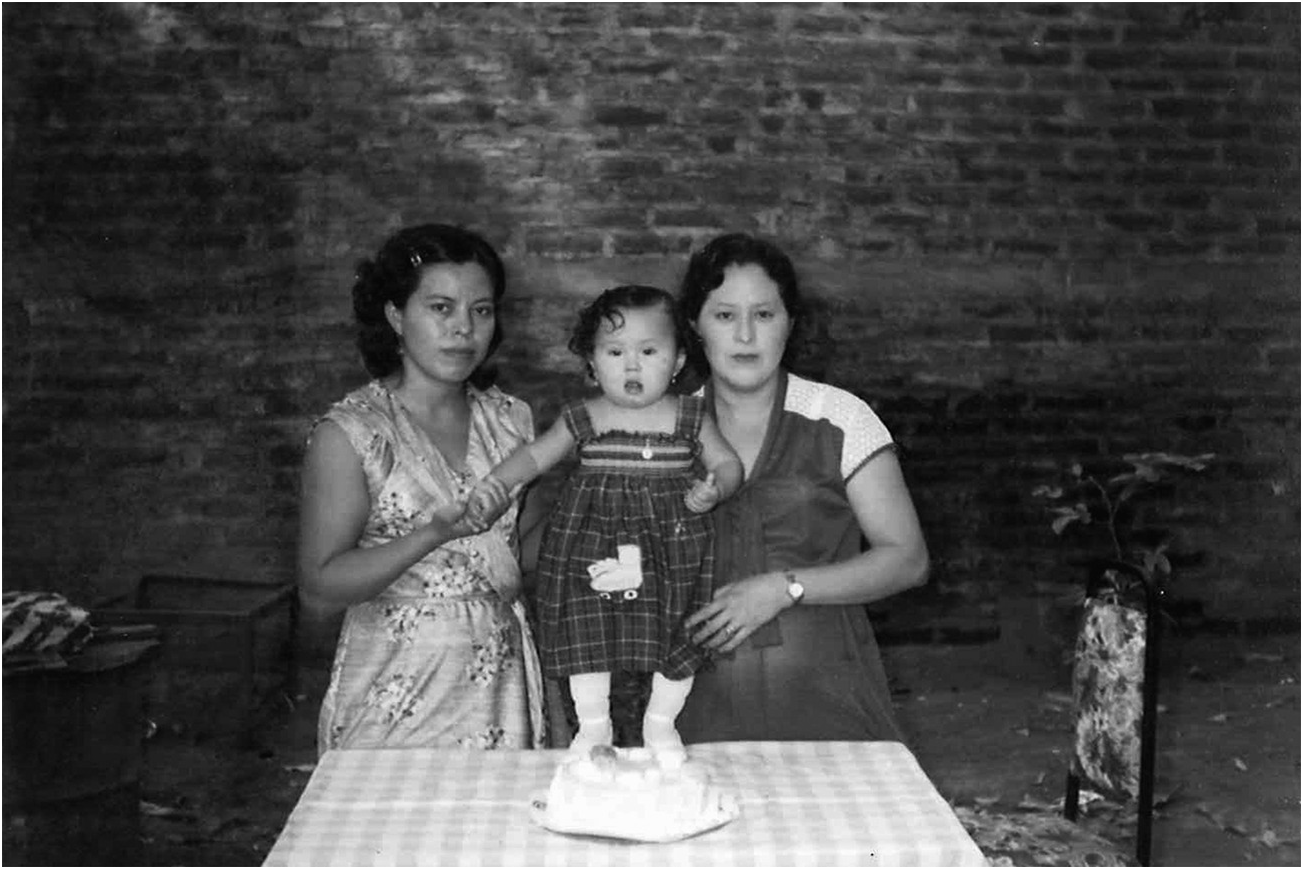

Figure 1.5 Gloria García with Pezca coworker

I don’t know if we felt liberated but we would even joke during work hours, we were happy. Was it the union support or were we just tired of being in that position? Things changed. We would not get scolded or threatened to have our daily wage taken away from us for talking. We felt free!Footnote 60

The sense of liberation was generally confined to the plant floor. Yet, female union participation also contributed to personal transformation. Union education seminars had a major influence on Gloria and her compañeras. She recounts: “I wasn’t always a talker. I was timid. It was when I went to the union educational seminars that I learned to talk. After that, no one could shut me up.”Footnote 61

Many female workers were single mothers, most of whom depended on extended family networks to care for their youngest children. According to former plant workers, single mothers saw less incentive to get married. Upon returning from work, however, the “second shift” of cooking, cleaning, and caring for children kicked in. The double shift was intensified for married workers, as they had to provide for their often quite demanding husbands or compañeros. Some testimony suggests that despite the significant increase in family income, female work put a great strain on marriage. For temporary workers, the strains were greater as there were changes in shifts and during the chacalín season, many worked the night or midnight shift. As Gloria García recalls, “The guy would get ticked because his wife didn’t have his food ready or his clothes washed because she was working. So he looked elsewhere … men always look for el plato ajeno”Footnote 62 (a different meal – woman).

Union activism placed even greater strain on families. Gloria recounts that when she was elected to the SIP leadership, her husband posed an ultimatum: “Either the union or me and the kids!” She responded, “Well you can go but you’ll leave the kids with me.”Footnote 63 He moved out. Other marriages also broke up over female union activism. It is difficult to chart the relationship between the development of class consciousness among women and the rise of gendered forms of consciousness that led to individual resistance against male patriarchy. Yet, in the case of Gloria and other activists, there seems to be a clear correlation.

There were also sharp limits to the union’s ability to accommodate the proto-feminist discourse that was emerging; no one challenged the notion that women had certain naturally endowed characteristics: more nimble hands to peel and sort shrimp and a predisposition to cook, clean, and nurture her family.Footnote 64 No women operated or repaired machinery. Finally, as noted, the most important three positions of SIP General remained exclusively male.Footnote 65

Figure 1.6 Gloria García with her sister, Concepción García and her sister’s daughter

Trouble at Sea

If SIP could overcome the effects of the gendered division of labor in the processing plants, they had much more trouble dealing with the machista lifestyle of the marineros (fishermen), rooted in the perils of work on the high seas. One former fisherman described that labor as like being in prison – others compared it to slavery.Footnote 66 Both metaphors indexed the fishermen’s absolute subservience to the captain and to their entrapment in a world of hard labor for 12 days and nights at a stretch.

Figure 1.7 Shrimp fishing boat

The boats usually plied the seas between 3 and 10 miles from the coast (although they often infringed the three-mile limit imposed for ecological reasons) and roughly 40 miles east and northwest from Puerto El Triunfo. Most trips lasted 12 days and involved at the very least 16 and often 20 hours of work a day. On each boat, the three marineros (fishermen) and the extra hand cast and hauled in the 65- to 75-foot nets on both sides of the boat every four hours.Footnote 67 They emptied the nets onto the deck and then they separated the fish, shrimp, and the chacalines. While two or three of the fishermen cast the nets again, the third one (and occasionally an “extra”) had the time-sensitive task of cutting off the heads of thousands of shrimp and then tossed them into the brine tank.Footnote 68 A mechanic (who earned 50 percent more than the others) was in charge of the maintenance of the motors. In addition, he helped with the nets and spelled the captain at the wheel. One of the marineros doubled as a cook.

When the boat arrived back at the dock in the Bay of Jiquilisco, the crew had to wait. At times, the marineros helped the dockworkers unload the shrimp and fish and earned an extra two dollars. Regardless, the rest of the crew had to wait until the product was weighed on the docks: The water and ice stuck to the shrimp was discounted. They were also allotted 20–25 pounds of fish that they received upon completing the voyage. The captain designated one of the marineros to guard the boat for 24 hours, receiving two dollars for his time. The crew would be paid, between 6 and 24 hours after docking and then would have to be ready to disembark again within 48 hours.

A ground crew was in charge of unloading the shrimp and cleaning the brine tanks. They shoveled the shrimp into metal tubs and loaded them onto pick-up trucks that transported the catch to the plant, where the shrimp were weighed again. The laborers who worked on the pier and in the varadero represented between 10 and 15 percent of the plant labor force. Because they tended to have much contact with the fishermen, SIP and Sindicato Agua (the breakaway union founded in 1971) vied to recruit these workers into their ranks. The situation was complicated by the “eventual” status that the companies accorded to the varadero workers. Moreover, the divisions between the unions were not so clear. Thus, for example, SIP represented the 59 fishermen who worked for Mariscos de El Salvador (1980) and most of the 90 fishermen (including captains) who worked for Atarraya.Footnote 69 The large majority of the roughly 200 fishermen who worked for the seven companies affiliated with Pezca S.A. belonged to Sindicato Agua. Legally Pezca S.A. was only a processing plant, but its owners also possessed controlling shares in the fishing companies. That arrangement helped the company and its stockholders deal with tax liabilities. It also gave the company an advantage in labor relations because it further divided the labor force.

There was also straight-out competition between the unions. During the late 1970s, SIP made inroads into the base of Sindicato Agua, largely due to the latter’s ineffectiveness in negotiation. In February 1976, for example, Molina Lara reported to the SIP assembly that 78 marinos had joined SIP because “el sindicato hermano” (brother union) refused to back up their demands.Footnote 70 The relations still seemed amicable as the “hermano” designation suggested. In December 1976, Molina Lara urged each of the 500 SIP members in attendance to help foster closer ties with Sindicato Agua. Similarly, another union official urged members to “make the fishermen conscious of the need for unity.”Footnote 71. Many plant workers and fishermen viewed Sindicato Agua as “patronalista” (pro company) and corrupt. Since its inception, Sindicato Agua relied on strong support from the captains linked to Pezca S.A. and, in turn, the clientelistic links between the captains and their crews.

Although the competition over membership was a source of discord between the unions, the machista lifestyle of the fishermen tended to especially alienate the female base of SIP, some of whom were married to or lived with marineros. In those family units, often the female belonged to SIP and the male to Sindicato Agua. Many fishermen rationalized their machista behavior in the port as a consequence of their work. The 12 days at sea, often harrowing and always exhausting, conditioned them to, as it were, fulfill the stereotypical image of fishermen in port. As one former marinero confessed: “[W]e were degenerates.”Footnote 72 The epitome of this degeneracy in many port workers’ memories was the frequent appearance of skiffs filled with prostitutes as the fishing boats entered the Bay of Jiquilisco just before arriving at the port. The prostitutes’ payment in shrimp only adds flavor to the tale of corruptionFootnote 73. Port residents, including their compañeras and kin, viewed the fishermen as inveterate womanizers and alcoholics (binge drinkers in our parlance). “We often didn’t even go home – we just went straight to the bars, the billiard parlors, and the whorehouses.” Another commented, “We felt we were owed the release.”Footnote 74 Such behavior was not well received by many female family members and plant workers. One former plant worker recalls with disdain: “Some captains kept four or five women.”Footnote 75

La Movida

The patrones de barco (captains) and the crew could indulge their vices due, in no small measure, to “la movida,” that is illegal sales to “pirate merchants” on the high seas or deserted beaches. This practice allowed marineros to earn from US$400 to US$800 a month (at times much more) in addition to the US$100 a month that they usually garnered during the late 1970s. The captain’s share reached US$2,000 on some voyages. This unique form of resistance arose as a form of “life insurance” in response to Pezca’s failure to indemnify the families of 10 fishermen lost at sea in in the cyclone of May 1977. In the words of one fisherman, “We thought, ‘if this is what our life is worth to the company, I’ll take an advance on my insurance.’”Footnote 76

For fishermen, there was a moral economic dimension, rooted in a sense of the asymmetry of risk and a calculus of economic justice. They risked their lives daily to fill up what had been “empty bins” when they set sail; the company only “risked” the cost of food and fuel.Footnote 77 Many fishermen justified the sales as a direct appropriation of the value of their labor and as a form of resistance against an inhumane and rapacious management.

Most fishermen claim that this form of resistance developed following the cyclone. Yet, Noé Quinteros and others stress that the practice originated before 1977. Archival evidence supports their argument. Artisanal fishermen known as murrayeros would come alongside the shrimp boats to receive gifts of murraya, or surplus fish of little value. Some murrayeros began to commercialize some of the shrimp catch. In June 1975, Leonel Chávez denounced the hiring of police agents, known as AVIC (Asociación de Vigilantes de Industria y Comercio) disguised as private security to deal with this very minor problem. In September 1975, Quinteros argued that the AVIC’s 47 agents (for 39 boats) absorbed 400 colones per month per agent in addition to their food expenses. Rather than waste the money, “[T]he company should raise salaries for the workers suffering from severe inflation.”Footnote 78 For Quinteros, la movida became a generalized form of resistance in direct response to management repression.Footnote 79

Regardless of the precise origin of la movida, in the words of Ruperto Torres, after the cyclone, “[T]here was an explosion of sales. Everyone wanted to shell shrimp.”Footnote 80 Until the late 1970s, packinghouse workers and their union leadership grudgingly accepted the practice, in part because of the shared outrage toward Pezca management following the cyclone. The extra income provided to spouses and kin of the fishermen mollified any opposition. Many came to justify the sales as a form of direct appropriation of the value of their labor or as a form of resistance. In the words of one female packinghouse union activist: “Well, once they had filled up the storage tank for the company, they should get what they produced.”Footnote 81 Yet there was clearly a darker dimension to “la movida.” High-level military officers figured among the merchants. A clear example of military complicity in the illegal activities occurred when a colonel fired two National Guardsmen because they had arrested the employees of a major “pirate” operation.Footnote 82

By the late 1970s, the companies began to urgently seek solutions to the problem of “la movida.” On one flank, they launched a publicity campaign.Footnote 83 They blamed the rise in local prices on the robbery, which curiously they did not pin directly on the fishermen. Rather, the National Guard and Treasury Police agents went after the putative buyers, harassing the local artisanal fisher population, arguing that the pirate merchants came from that sector.Footnote 84 Artisanal fishermen denounced “una verdadera cacería” (a true hunt) against them. The agents not only arrested some artisanal fishermen caught with shrimp, but they also extorted others, demanding the shrimp or cash.Footnote 85

The companies viewed the artisanal fishermen as a nuisance, especially when company fishing boats entered the prohibited three-mile fishing area reserved for artisanal fishermen or when they accidentally captured shrimp larvae in the mangrove estuaries of the Bay of Jiquilisco. The response of the artisanal fishermen to the repression eloquently announced an historical moment decidedly adverse to the owners. A group of fishermen arrived at an opposition daily, where they claimed that they represented 15,000 more who for generations had fished in the waters of Jiquilisco and off the coast. The “monopolies” along with the regime were intent on depriving them of their livelihood.

Who are the thieves? Those who believe that God created the sea and its products for all people or these businessmen who believe they have some kind of titles signed by who knows who that makes them the absolute owners of the sea.Footnote 86

This discourse of natural law may well have existed for generations as a “hidden transcript” among sea-faring folk on the Bay of Jiquilisco. Yet, in the context of heightened class tensions in the port, these fishermen could publicly enunciate this anti-monopolist discourse. There was interaction and some overlap between artisanal fishermen who resided in hamlets surrounding the Bay of Jiquilisco and the fishermen and workers of Puerto El Triunfo. Some Pezca marineros also fished in Jiquilisco as artesenales. Thus, the labor struggles surely had an impact on the artisanal fishermen as did peasant struggles that were sweeping the department of Usulután. For the companies, these ragged artesenales with their radical rhetoric added yet another dimension of increasingly bitter class antagonism.

* * * * *

The consciousness and practice of the Puerto El Triunfo working class changed substantially between 1970 and 1977. First, the level of participation in the unions increased dramatically, from less than 200 attendees at SIP General meeting to more than 500. Union local meetings witnessed analogous increases. The larger meetings naturally reflected the increase in the number of union members, primarily females, in the plants. Because Salvadoran law did not permit closed shops, increased union membership hinged on the persuasion of the unaffiliated.

The decade also witnessed a substantial increase in female activity in the unions. Indeed, women ascended to leadership positions especially in the locals and actively participated in union meetings, often pushing their male compañeros toward more militant positions. Victoriana Ventura, for example, exclaimed in a union meeting, “We have to be brave! Don’t let the bosses get their way! Don’t let them achieve their objectives!”Footnote 87 Their participation and militancy formed part of a process whereby female workers were able to articulate and win demands of particular concern to them like first aid dispensaries (for the chacalín peelers) and simultaneously exert growing control over the production process. Moreover, they were able to create democratic forms of sociability on the plant floor that gave them a daily glimpse of a different kind of society. Female workers, especially on the night shift, joked and played games. They exuded a new sense of power that kept management at a distance.

The sense of liberation did not translate into a full-scale transformation of the family. Husbands and fathers continued to exert strong patriarchal control and female workers often resisted those venerable chains, particularly around finances. Gender conflict reached a higher level of intensity with marinero spouses. Domestic violence occurred with some frequency.Footnote 88 A significant percentage of women either divorced or remained single, secure that their union wages and extended family would allow them and their families to survive with dignity.Footnote 89

The transformation of consciousness also involved an increasingly salient political element, though one that was largely circumscribed by a strong notion of syndicalism. As we shall see in Chapter 2, the conceptual key to the transformation lay in the terms interest and solidarity. Over the course of the decade, plant workers expanded the meanings of those terms so that increasing numbers of workers viewed state or management repression against unionized workers elsewhere in the country as an attack on their own self-interest. The contact of the union leadership with leftist organizations through their participation in the labor federation FENASTRAS spurred the broadening of those meanings. Moreover, they injected a militant syndicalist vocabulary into discussions among workers.

Deborah Levinson’s analysis of the Guatemalan labor movement in the late 1970s is appropriate for this brief moment in Salvadoran working-class history right before labor’s destiny became tied to the revolutionary movement. She writes:

Although they had no revolutionary program, trade unionists disclosed possibilities for exceptional, radical social being and action. They wanted to live beyond the real limits, and they pressed for the creation of a world of resistance that was no one else’s project or property, a countersociety always busy with the details of thoughtfully combating the barbarism that threatened it.Footnote 90

The struggles of the female port workers were similar to those in other countries in that they contributed dramatically to the defense of the union when under assault. As Greg Grandin writes, “In Guatemala, as elsewhere, during moments of crisis, the institutionalized segregation of the public from the private broke down and women carried what was often an aggressive defense of their communities.”Footnote 91 Female leaders like Gloria stuck with the union until death stared them in the face.

The experiences of Puerto El Triunfo were reflective of broader transformations in Salvadoran society and thus allow us to recognize the process of labor mobilization and radicalization in other parts of the country. The classic narrative of state repression radicalizing popular organizations holds true, only to a limited extent in the port. No doubt there was a slight radicalizing impact of the National Guard assault on union headquarters during the screening of the Soviet film in 1977. Yet, this was an isolated incident until December 1980. Rather, the transformation of the union responded primarily to endogenous factors, in particular the labor-management struggle over wages, working conditions, and labor rights. At the same time, the transformation was extremely uneven as significant sectors of the port unions remained politically conservative, sympathetic to management, and hostile to notions of solidarity and equality. And, a key sector of the labor force, the fishermen, remained apathetic at best in relationship to the SIP demands for solidarity.

The successes of SIP, measured by a growth in real wages and improved working conditions and benefits, would have been inconceivable without the emergence of an insurgent leadership group in the early 1970s and their openness to a form of proto-feminism that circulated among some female workers. Yet, the success of those leaders entailed, as we saw, the creation of new dependent relations, if radically different than the prior union leader-client relations. That dependency, in turn, created a sense of ambivalence among the rank and file about ideas and actions that came from the top down. At the same time, however, female workers increasingly joined the ranks of leadership injecting new concerns and ideas into the union discourse.

As we shall see in Chapter 2, 1978 and 1979 would mark the highpoint of labor mobilization and militancy when, proportionately, El Salvador ranked only behind Brazil in Latin America in terms of strike activity. Moreover, as a distinct sign of their militancy, Salvadoran workers occupied more factories than anywhere else on the continent. And the port workers played a major role. The newly mobilized women and the insurgent leaders in Puerto El Triunfo would have their mettle tested as they were thrust into a violent and rapid cycle of state repression and popular resistance.