铁饭碗

The iron rice bowl

靠天吃饭

Relying on heaven to eat

上有政策,下有对策

Policy above meets counter-policy below

In 1968, aged eighteen, Ye Weili, an “educated youth” (zhiqing) from Beijing, was sent down to a poor village in Shanxi Province. As the child of two mid-level cadres, Ye’s schooling had been characterized by a high degree of gender equality, and at home domestic work was done by a maid, whom her parents were entitled to employ because of their work for the CCP. In the villages, Ye experienced very different forms of gender relations:

I was the only female laborer on my team regularly working in the field. Only occasionally would some unmarried young women join us (…). When we first arrived some villagers privately inquired whether any of us would consider taking a local husband, assuming a city girl would not fetch a big bride price. Once they realized that we were not interested, they left us alone.Footnote 1

The food too was different, both in kind and in quantity, from what she had been accustomed to under the urban rationing system:

What we ate every day at the zhiqing canteens was corn bread, millet porridge and preserved cabbages and carrots. At first food was rationed because there wasn’t enough of it (…). Later grain was no longer a problem, but there were hardly any fresh vegetables, let alone meat. Because of this poor diet, every time we went back to Beijing for a visit we would bring back foodstuffs such as sausages and dried noodles.Footnote 2

As her time in Shanxi wore on, Ye came to worry that she might never be permitted to leave the countryside. However, in 1972, universities across the country were finally able to begin enrolling new students – the first round of admissions since 1966. Ye was selected to become a “worker-peasant-soldier student” at Beijing Normal College, and she returned to the urban world. Social status had played an important role in her selection. Ye’s background as the daughter of middle-ranking party cadres had been displaced by a new, more favorable classification as a “peasant.” Ye, who graduated in 1976, would go on to leave China for an academic career in the United States.

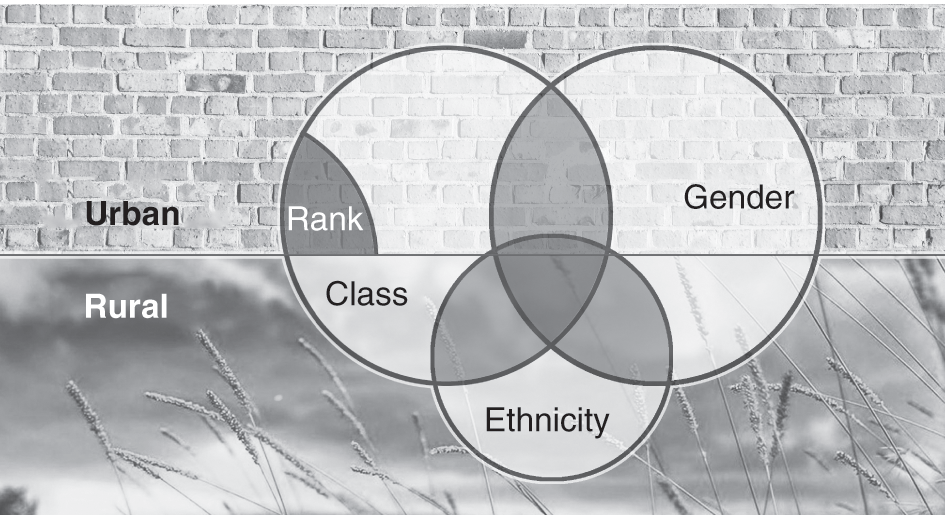

Ye’s story makes clear the importance of hierarchies – gender, age, class, urban versus rural – to understanding life in Maoist China. It is also obvious that these hierarchies and labels intersected with one another: the position of urban women in society differed from that of rural women, for instance. Furthermore, Ye’s experience shows that these social categories did not necessarily remain stable over time during the Mao era. In the countryside, Ye was excluded from the urban rationing system and could not be sure of ever returning to Beijing, let alone enrolling at university. We should keep in mind that labels that were important in one context might have no currency in another. Ye’s official ethnicity had little significance in Shanxi, where her fellow villagers, like her, came from the Han majority.

In this chapter, I characterize Maoist China as a society in transition. Unlike a capitalist society, social hierarchies were determined less by wealth and private ownership than by a series of official classifications. As suggested above, the four most important classifications (class status, urban/rural registration, gender and ethnicity) were never independent of each other.

By the early 1960s, almost every Chinese citizen was classified by the state according to the four major categories. The official distribution system for food and goods, along with access to information, higher education, employment, party membership and military service were all based on this complex system of classifications. This chapter also discusses informal modes of distribution of material goods that sat outside of official channels, such as theft or under-reporting. Finally, we consider the various waves of internal migration and show how they were linked to the classification system.

A Society in Transition

The fundamental dynamic driving Maoist China was the transition from a semi-colonial, underdeveloped country to state socialism. The stage was set for this transition by the twin victories of the 1940s. The triumph of the Allies over imperial Japan in 1945 and the Chinese communist revolution of 1949 freed China from its peripheral position in the global capitalist system, allowing the party to pursue one of its central goals: transforming a poor agrarian country into a modern industrial nation within a few decades. In the early 1950s, Cold War tensions and a US economic embargo kept China isolated from the Western world. American policymakers sought to cut off China’s supply of high technology and military hardware, compelling the PRC to “lean to one side” and seek closer links with the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc. However, in the late 1960s, Chinese concerns over the Soviet threat encouraged a rapprochement with the United States, setting the PRC on its way to becoming an internationally recognized state. This changing geopolitical background, however, did not result in China’s immediate integration into the capitalist world market. Once the attempt to create an alternative “socialist world market” with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe had stalled in the early 1960s, the PRC adopted a strategy of self-reliance, remaining mainly outside global production chains until 1978.

By 1957 China’s urban economy and population were mainly organized along state-socialist lines. State-owned and collective enterprises were embedded in a Soviet-style planned economy. Private accumulation of wealth through property ownership and exploitation of wage labor was prohibited from the socialist transformation in the mid-1950s until the beginning of the Reform era in the early 1980s. Leading cadres managed state-owned enterprises, but they exercised no rights of ownership and had no legal way to transfer profits from the work unit to their personal holdings. In place of the hiring and firing practices of a capitalist system, the permanent workforce in state-owned industries ate from the so-called “iron rice bowl” (tiefanwan), meaning that they “owned” their jobs and the associated social welfare benefits for life. Their labor was decommodified, with almost all employment being assigned by the state rather than sold on the open market.Footnote 3 Commodified labor did exist in the form of short-term contract work, but this practice remained marginal throughout the Maoist period.

By contrast, rural China under Mao was never more than semi-socialist. Attempts to eliminate private property and natural village boundaries failed spectacularly during the Great Leap Forward, forcing the CCP to allow mixed ownership structures in the People’s Communes and to distribute plots of land for private use to peasant families in 1961. Even at the height of the Cultural Revolution, this compromise with the peasantry never came under real attack in more than a few regions. Further socialization of land and the means of production proved impossible, and the peasant family remained an important unit of production and consumption. Nor was it possible to expand the socialist welfare state into the countryside. In general, the reach of the state remained far stronger in urban society than in the villages.Footnote 4 This was a critical point of difference between the PRC and the Soviet Union or the GDR (German Democratic Republic), where by the 1970s the whole population was integrated into the welfare state from birth to death. Chinese peasants, almost 80 percent of the population, never tasted the fruits of the “iron rice bowl.”

Marxism-Leninism and Equality

Critics of communism are fond of pointing out that in socialist states not everyone was equal. The ideology of communism, the argument goes, was little more than hypocritical cynicism, a rhetoric of convenience used by ruling cadres to dress up their dictatorship. This critique, however, fundamentally misrepresents Marxist theory. Marx and Engels themselves asserted that communism would not be delivered immediately following any revolution; instead, a transitional “dictatorship of the proletariat” would be necessary. The function of this dictatorship would not be to proclaim the equality of all people, but to create the conditions for the elimination of private ownership of the means of production, which would in turn render wage labor obsolete and dissolve class distinctions. It was only after these goals were achieved that the state as an instrument of class struggle would finally be extinguished.Footnote 5 Furthermore, Marx explicitly argued that the “bourgeois law” of distribution according to labor performance would continue to apply during the transitional period. Distribution according to individual needs was to be the province of communism, not the socialist state, and the achievement of such a system of distribution would have to await the development of appropriately advanced forces of production. Given the diverse needs of individuals, even this would not be an equal distribution, merely an equitable one.

Whatever their attitude to equality, communism’s founding theorists certainly never envisioned the “dictatorship of the proletariat” as requiring a one-party system. Nor could they have imagined the hierarchical system of ranks that would come to characterize Soviet-style Leninist parties. In contrast, Marx saw the Paris Commune of 1871, a decentralized grassroots democracy, as the best model for proletarian government.Footnote 6 The Chinese notion of a vanguard party that would first lead the revolution, then become a party-state after victory, was not a Marxist idea, but an import from the Soviet Union in the 1920s. It was this vanguard role that formed the justification for the special treatment and privileges afforded to CCP cadres after 1949. In another line of reasoning, the party claimed that such privileges were a necessary acknowledgment of the contributions and sacrifices of “old cadres” during the revolution. For the CCP, the vanguard party would be needed as an instrument of class struggle until the transition from socialism to communism had been completed.

The worldview of the CCP in the early 1950s was strongly influenced by Soviet Marxism-Leninism. However, during the Great Leap Forward in 1958 and later during the Cultural Revolution, Marx’s early writings such as “Critique of the Gotha Program” and “German Ideology” were widely discussed. Marx imagined a society in which the division between urban and rural, and between manual and intellectual labor, would be abolished. In his vision of communism, every citizen was to have a free choice of occupation according to their needs and skills, so that the same person could be a hunter in the morning, a fisherman at noon and a “critical critic” in the evening.Footnote 7 This focus on utopian thinking seems to me to make terms such as “fair wage” or “fair distribution” largely irrelevant in a Marxist context. These notions are more the province of traditional social democracy and Western welfare state. If we are to approach revolutionary regimes on their own terms we may need to abandon these notions, or at least recognize that they were not necessarily native to Marxist debate.

Marx’s ideas, especially the prospect of eliminating the city/countryside and intellectual/manual division of labor, had widespread currency in the second decade of CCP rule. Compared to its Soviet counterpart, the Chinese Party proved more interested in the “utopian” elements of Marx’s ideas,Footnote 8 but ignored his warning that the introduction of communism based on a backward means of production would only “generalize the dejection” that existed in pre-revolutionary society.Footnote 9

By comparison with other notable revolutions such as the French Revolution of 1789 or the Russian “October Revolution” of 1917, the Chinese revolution in 1949 was characterized by a high degree of mass participation.Footnote 10 This did not mean, however, that it was an organic, “bottom-up” revolution. Indeed, China in the 1940s experienced few spontaneous uprisings of workers and peasants compared to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Instead, the CCP expanded its power from its base in northern China via a civil war with Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalists (1946–1949) – in other words, through military conquest. The party built socialism from above, albeit with considerable mass support from below. Workers may have had more power on the shop floor after 1949, but the CCP’s dictatorial authority was always exercised in the name of the proletariat, never by the proletariat themselves. Workers had no democratic control over production.

Nevertheless, in the 1950s and 1960s the party leadership could count on millions of activists and “true believers” at the grassroots. Some scholars have argued that Mao was little more than a cynic, focusing on maintaining his own power to the exclusion of all else.Footnote 11 A desire for power, however, is not in itself incompatible with Leninist ideology, which sees taking and defending the apparatus of the state as key to effecting genuine political and social change. Allowing power to fall into the hands of “class enemies” or “revisionist elements” inside the party would inevitably lead, in this view, to a restoration of the old society. Neither Mao’s unceasing defense of the power of his so-called “proletarian headquarters,” nor the gruesome determination the CCP showed in eradicating its perceived enemies, necessarily prove that Mao and his followers were not genuine believers in the communist cause. Whatever his ultimate motivations may have been, no available archival evidence gives any sense that Mao did not believe in the communist agenda that he publicly espoused. That agenda, to be sure, was never realized, and people in Maoist China were very far from equal. That does not mean, however, that everything the CCP did under Mao was a cynical power play. The content of CCP policies mattered, and it is therefore necessary to ask questions about how those policies worked in practice and how the party dealt with the results.

The Intersectionality of Hierarchies in China

Intersectional approaches are well established in sociology. Current intersectional theory traces its roots to the 1970s, when feminists from minority backgrounds forcefully critiqued the mainstream movement for focusing on a binary opposition of “patriarchy” against “sisterhood.”Footnote 12 In their view, this simplified vision of gender relations failed to account for the race and class discrimination faced by women beyond the wealthy white communities of the Global North, forms of discrimination that were interwoven with gender prejudices in a complex tapestry of injustice. Gender, race and class, in other words, are intersecting qualities, and social hierarchies cannot be understood if each category is studied in isolation from the others. Class is gendered and gender has a class component; ethnic labeling tends to disadvantage the poorest the most. Industrial workers often draw their identities from particular definitions of masculinity: physical strength and a pride in manual skills. Light industry, by contrast, has historically been viewed as nimble, dexterous “women’s work.” From the 1980s, the textile, garment and electronics industries of developing countries were dominated by women.Footnote 13 These female workers were often (and continue to be) seen as easier to control than their male counterparts.

In approaching intersectionality in the Chinese case, I take account not only of systems of production and distribution, but also of reproductive labor, encompassing sexuality, child birth, child care and housework. This unacknowledged, unpaid “invisible labor” continues to be done, in large part, by women, and is existentially important to the functioning of societies across the globe. Much mainstream economic theory, however, either ignores the impact of this unremunerated labor, or else takes it as read that women are natural care givers for whom reproductive work is an automatic instinct. Orthodox Marxist approaches likewise discount care work as “non-productive,” in the sense that it fails to produce surplus value. My own research adds to the growing consensus that the invisible labor of reproduction is not only the province of gender studies, but is in fact an essential part of the wider socio-economic picture.

In a capitalist society, surplus value is extracted by ownership of the means of production, land and capital and through the control of wage labor. In modern societies, the state plays a significant but generally limited role in distributing the resulting wealth through taxation, subsidies, investment programs, social welfare, provision of education and so on. In Maoist China, the limitations on private accumulation of wealth made the state a far more important distributor of resources than in most contemporary societies. Distribution of goods, along with access to economic and political organizations, programs of affirmative action and the allotment of social capital, was based on a systematic categorization of the population.

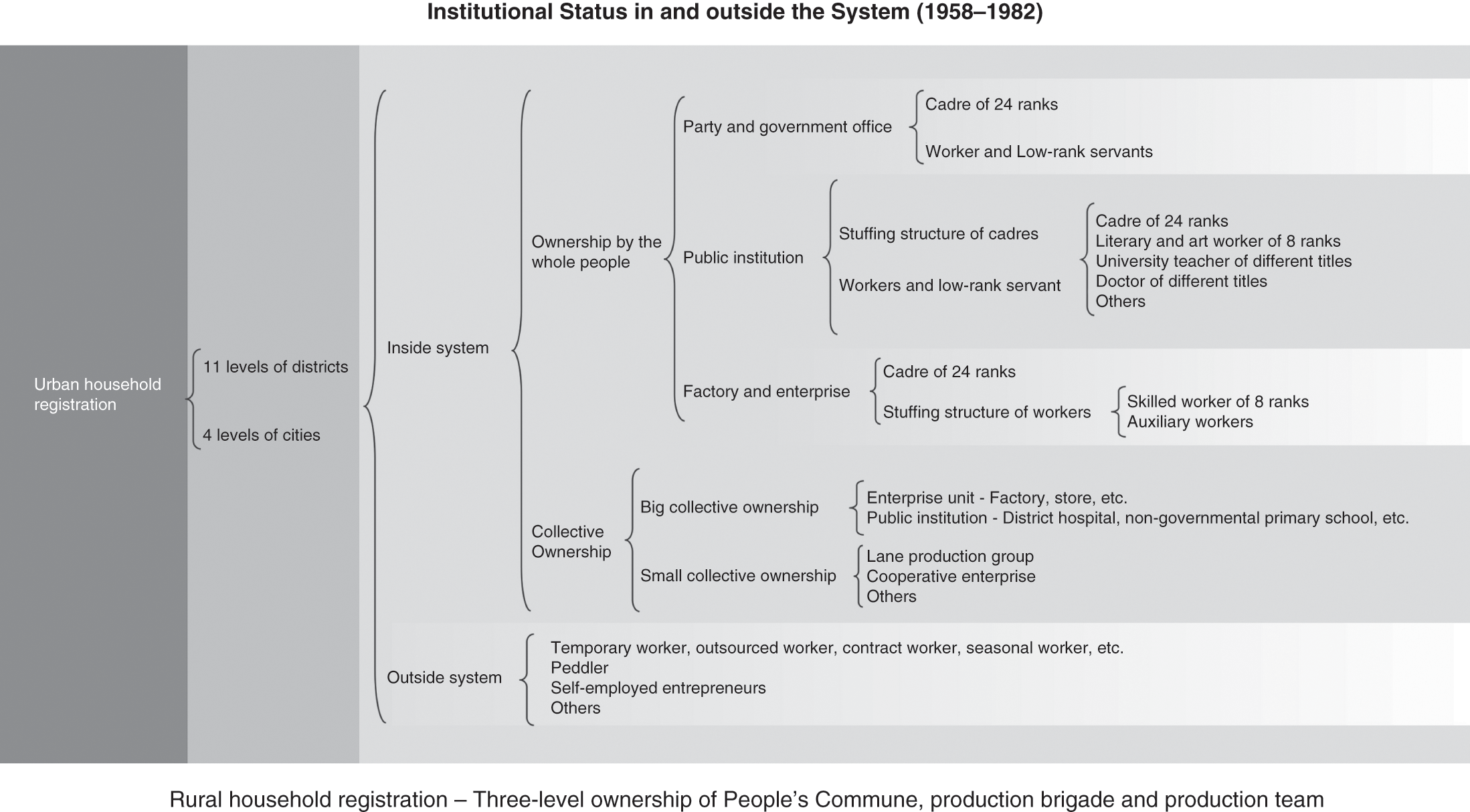

The most important division concerned participation in the urban welfare state, with every Chinese citizen labeled as either “inside the system” (tizhinei) and “outside the system” (tizhiwai). This division ran largely along urban/rural lines: anyone with a rural household registration fell “outside the system” (Figure 1.1). This included peasants in the urban suburbs, who retained their rural registrations but were counted in the urban population statistics in the 1950s. Some urban residents, such as temporary workers and small traders with no assigned work unit, also remained “outside the system.” Minimal welfare provision existed for those categorized in this way: outside the cities, even cadres were not paid by the state or entitled to welfare benefits unless they worked above the level of the People’s Communes. Inside the cities, meanwhile, a complex system of ranks governed wages and the distribution of goods.

Figure 1.1: Institutional status in and outside the system (1958–1982).

Beyond the urban–rural divide, every Chinese citizen was officially labeled in terms of class, gender and ethnicity. I therefore identify the following major types of classification:

household registration (agricultural versus non-agricultural)

“rank” (a sub-categorization assigned to urban residents)

class status (combining occupational status, family background and political labels)

gender (male versus female)

ethnicity (Han versus ethnic minority).

It is important to note that classification under these categories did not necessarily reflect the self-identity of the person concerned: some of China’s fifty-five recognized national ethnic minorities, for instance, were 1950s inventions that bore only a partial relationship to the autonyms used by people on the ground.

By the late 1950s, labeling according to these five categories was complete for almost the entire population, with the exception of some minority areas such as Tibet where the process would continue until the mid-1960s. Household registration, class and ethnicity were all closely linked to family. Ethnicity and family background were defined through the paternal line, while household registration was passed down on the mother’s side.

The Urban–Rural Divide (Household Registration)

The difference in the treatment of urban and rural areas in the early PRC was so stark that China under Mao is sometimes described as a “dual society.”Footnote 14 By 1958, almost every citizen in the country’s Han Chinese areas was classified with an agricultural or non-agricultural household registration (hukou).Footnote 15 People with urban status were entitled to buy food and important consumer goods at low prices using ration cards provided by the state. Most of the urban population was organized into work units (danwei) and entitled to social welfare and cheap housing.

This state-subsidized urban society was made possible by extracting resources from rural areas. Rural-registered peasants were organized into collectives and compelled to sell any agricultural surplus above a prescribed level to the state, which had a monopoly on sale and purchase and imposed consistently low prices. A rural hukou carried no entitlement to a state ration card, wages or social security, which were replaced in the collectives by work points (gongfen) that could be exchanged for grain. Almost every peasant was a member of an agricultural cooperative from 1956 and of a larger People’s Commune between 1958 and the early 1980s. Within communes, party branches were established on the level of the production brigade, and at the lower levels individual households were grouped together in small production teams from 1961 onwards.

For much of the Mao period only small amounts of currency circulated in the countryside. A production team’s income depended heavily on labor performance. The lack of an effective system of redistribution in rural areas meant that weather could have a serious impact on local collectives, and peasants in more developed areas typically ate better than those in poorer ones. In provinces such as Henan, the diet of the rural population would rely on sweet potatoes, widely regarded as “pig food” in the richer south, until the early 1980s. In addition, because minimum rations were not clearly defined, rural distribution was subject to far greater manipulation by local actors than was possible in the state-organized urban supply system. In times of crisis, rations might still be distributed, but the food was of poor quality and had little nutritional value. Rural welfare did exist in the form of initiatives like the “five guarantee household” program, which provided food, clothing, heating, medical care and burial. These, however, were locally financed and reached only a few percent of the rural population, mainly orphans and disabled or elderly people without family support. Beyond these protected groups, rural society was mainly self-reliant, with peasants receiving relief from central state funds only in the case of severe natural disasters. Some people in the countryside did escape rural registration: workers on state-owned farms and factories could often maintain their urban hukou.Footnote 16 Genuine upward mobility from rural to urban status, however, was very limited during the Mao era after 1962. It was much more usual for the government to downgrade the status of urban people and send them to the countryside, as in case of the “urban youth” exiled from the cities during the Cultural Revolution.

It is often argued that class was the most important category in Maoist China, but in terms of the distribution of basic goods and services such as food, clothing, housing or health care, class was actually less important than the urban/rural divide. The urban supply system ensured that a “capitalist” in Beijing would eat better than a “poor peasant” in central China, despite the latter’s far more favorable class status. Moreover, the “dual society” phenomenon was one of the major push factors for internal migration. The state attempted to control this migration, especially after 1962, by linking access to the supply system to legal residency in the cities. The limited options left open to peasants seeking an urban household registration included serving in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), passing the national university entrance examination or being recruited by an urban work unit as a permanent worker. All were a realistic prospect for only a vanishingly small segment of the rural population. Marrying a worker with an urban household registration was a dream for many women in the countryside, but this form of upward mobility was neutered by the fact that the hukou status of children was passed down through the maternal line.

For the vast majority of people, therefore, being a rural citizen meant exclusion from the socialist welfare state in an existence tied to village and land. The model of development during the Mao era was essentially to develop urban heavy industry through exploitation of the peasantry and extraction of rural resources at artificially low prices.Footnote 17 The urban–rural divide was the foundational division of Chinese society under Mao, the matrix on which class, gender and ethnicity intersected. To put it in more Maoist terms, the divide was an expression of the contradiction between the socialist and semi-socialist elements of Chinese society under the early PRC. (See Figure 1.2.)

Figure 1.2: Intersectional hierarchies in Maoist China.

This great divide, enduring though it has proved, did not go unchallenged. Despite the difficulties, people could try to change their status from rural to urban. The urban bias of the distribution system and exclusion of the rural population from the welfare state also came under occasional attack as unfair and unjust, particularly in 1956–1957 and during the early Cultural Revolution. In these periods the party leadership struggled to justify why expansion of the “iron rice bowl” was not possible, and some concessions for people “outside the system” were eventually made.

Urban Ranks

Geography played a key role in consumption and distribution during the Mao period. Four levels of administration existed within each of the Chinese provinces, from municipalities under the authority of the central or provincial government down through districts, counties and townships (see Figure 1.1). Below the county level even cadres were in most cases not on the state payroll but drew their salaries from local coffers. For those “inside the system” above this level, a scheme of subranks governed the distribution of resources, and here again spatial stratification was at work. The country was divided into eleven urban areas with varying wage levels to take account of differences in the cost of living, with Shanghai top of the pile.

Figure 1.1 highlights the role of another important division, that between state-owned and collectively owned enterprises. Workers in the state sector were entitled to much better welfare than in the collective sector and enjoyed a far higher degree of job security. The state-owned sector was divided into political work units (covering the party and the state apparatus), public work units (covering education and culture), and industrial work units. Within these three kind of units, employees were divided between cadres and workers, with university graduates considered professional cadres.

Figure 1.3: Diplomatic compounds in Beijing, Jianguomen, 1974.

Among industrial units, heavy industry received more resources than light industry, while state-owned enterprises were prioritized over those under collective ownership. Manual workers in key heavy industries received higher grain rations than those engaged in light or intellectual labor such as cadres or students.Footnote 18 These differences were justified mainly through Marxist-Leninist ideas of productivity, under which labor outside of industry and agriculture (such as housework) was regarded as non-productive. Differing rations were also an acknowledgment that manual labor was simply more calorie intensive than other forms of work. In 1955, cadres were divided into thirty ranks, with salaries and access to goods varying accordingly.Footnote 19 For instance, the two officials of the first rank (the chairman of the CCP and the prime minister) received a monthly salary of 560 yuan. The lowest rank consisted of service staff, who received 18 yuan per month. A number of scholars have therefore argued that the wage gap between top and bottom in the Chinese public sector was actually larger than in developed capitalist countries in the same period.Footnote 20

As well as formal position, length of service also played a role in the ranking system. Skilled “old workers” who had entered the workforce before 1949 received higher salaries than those who became members of work units later. This applied even to workers at the same level of seniority within an enterprise. To this day, “old workers” continue to receive more generous retirement benefits than their colleagues. For cadres, the year in which they joined the party was the key factor. “Revolutionary cadres” who had joined before the founding of the PRC were understood to have risked far more for the cause than those who entered the party after 1949, and this signal of political reliability meant deficiencies in their family background could be more readily overlooked.

As well as goods and services, rank also determined access to information. News on sensitive topics such as local protests, the underground economy or developments in other socialist countries was shared with only a select few. The so-called “internal reference” documents (neibu cankao), internally circulated news reports collected by the state-owned Xinhua News Agency, were received only by high-ranking cadres. Likewise, only people at the higher levels could read speeches and documents in full. For lower-ranking cadres, speeches by Mao and other leaders were often cut, while the ordinary reader would have access only to a newspaper summary.Footnote 21 Instructions and documents from the CCP Central Committee, its central decision-making body, were often circulated only at the provincial and county level but not below, with local cadres seldom gaining access to any central documents. In poorer parts of rural China, society remained almost completely paperless and peasants had little access to newspapers or books, leaving rural cadres to circulate instructions and propaganda orally or on blackboards. Many foreign non-fiction books were translated for “internal use” only. “Internal screenings” of Western movies were organized for cadres and party members, who were considered more capable of withstanding “bourgeois influence” than the general public and were trusted to watch for the purpose of information only.

This system of information control was effective but not flawless. Relatives of cadres would sometimes lend “internal books” to their friends, expanding their circulation beyond the government’s intended readership. Timely access to information about the twists and turns of central policies could save one’s career, and the regulation of information according to rank soon spawned a cottage industry of rumors and “news from the byways” (xiaodao xiaoxi) circulated by word of mouth.

Class Status

As intimated above, a person’s class status played only a limited role in the supply system. Class mattered far more, however, in terms of access to institutions such as universities, the army or Communist Party after 1949.Footnote 22 The categorization of classes began in rural China as part of the Land Reform campaign (1947–1952), where class labels determined whether an individual would be allotted land and a house or have their property confiscated. In urban areas, the state’s assignment of class labels was less systematic.

The system of class status was complex, generating labels based on three dimensions: the pre-1949 economic status of the family, called family origin (jiating chushen); the personal status of an individual based on current occupation (geren chengfen); and the individual’s political performance (biaoxian), including their attitude towards the revolution and the ongoing construction of socialism as well as their “social relations” (shehui guanxi). For people of bad family origins, it was important to “draw a line” and break with their problematic relatives. Party members were warned against forming friendships with “landlords” and other undesirable elements. Before the Cultural Revolution, members of the CCP or mass organizations like the Communist Youth League were seen as more politically conscious and reliable than the ordinary masses. The CCP in particular considered itself the vanguard of the proletariat and the Chinese nation, with membership restricted to only a small percentage of the population during the Mao era.

It is important to emphasize that the leadership of the CCP never clearly defined how the three elements (family origin, personal status and performance) were weighted when evaluating individuals’ class status. Cadres in some parts of the countryside made no distinction between family origin and personal status. In these areas, the son of a “rich peasant” could expect to receive the same label as his parents even if he was born after Land Reform. The class statuses themselves were a mixture of economic and political categories. In the cities, the most favorable categories were “revolutionary cadre,” “family of a revolutionary martyr” and “industrial worker.” At the other end of the spectrum sat categories such as “capitalist,” “rightist” or worse still “counterrevolutionary.” This last group was divided into “historical counterrevolutionaries” and “active counterrevolutionaries.” “Historical counterrevolutionary” might mean that a person had opposed the party before 1949 or had served as an official for the Nationalist government or in the Japanese occupied areas. Even somebody without historical problems could be labeled an active counterrevolutionary for recent actions or complaints. A cadre who had confessed to crimes while a prisoner in enemy territory would also be said to have “historical problems.” The various political campaigns of the Mao era added many new political labels for their targets, whether cadres, intellectuals or ordinary people.

In the countryside, “poor and lower middle peasants” were regarded by the party as its most reliable allies, while “middle peasants” who had more to lose from the collectivization of agriculture were to be neutralized. “Rich peasants,” “landlords,” “counterrevolutionaries” and “rotten elements,” meaning criminals, were viewed as enemies to be isolated. These foes, collectively known as “the four elements” (silei fenzi), were attacked in various campaigns and placed under “the supervision of the masses.” Cadres would frequently assign them undesirable or dangerous work such as cleaning out village latrines.

In this context, it was of little importance whether labels imposed by the state matched social and economic realities. Whether a middle peasant was really a middle peasant or rural residents identified with the Marxist-Leninist class system did not change the impact that these classifications had on their day-to-day existence. Class status was the primary factor determining access to or exclusion from the Youth League, the party, the army, public service and higher education. Those with a favorable class status often adopted the Maoist lexicon to bolster their social capital in negotiation with state agents or in struggles over resources.Footnote 23 The classification system thus became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. People in the various classes either adapted to it or else resisted the labels which they were assigned. A constructed “class” consciousness became a reality for many Chinese after 1949.

With no clarity from the party on the issue, the relative importance of the three elements of class status continued to shift over the course of the Mao period. People were born into their family origin, but it was the job assigned to them by the state that often did more to define their individual status in urban society. The impact of family labels on personal behavior was also limited by the fact that such labels were essentially set in stone. It was possible to petition the government for a change in family origin if it had been inappropriately assigned, but such changes were rarely granted. A more common way to improve one’s status was to use the opportunity of a new political campaign to display a good political performance. As the element of their political status over which people had the most control, performance was crucial to future prospects.Footnote 24

With the exception of the chaotic years of the early Cultural Revolution, it was the party and its organs that acted as the institutional gatekeepers regulating inclusion or exclusion from, say, university or the PLA. At the same time, party organizations were also the “referees” who approved changes in status and evaluated political performance. Hence, every Chinese citizen was dependent on the CCP, making it impossible, given the speed with which the political winds shifted and performance metrics changed, to ever feel entirely secure in one’s position. During the early Cultural Revolution, young people from families with an unfavorable class status demanded the right to participate in the movement, with some even questioning the system of class status as a whole (see Chapter 6). The ambiguity of class categories and their potential to produce conflict led the party leadership to produce several decisions during the Mao era clarifying labels and the meaning of the “class line.” Nevertheless, the importance of these labels in everyday life meant that they would continue to be a source of social conflict throughout Mao’s rule.

Gender

As with many other modern societies, the Chinese state has elected to categorize its citizens as either men or women. Third genders, like those now recognized across the Tibetan border in Nepal, have been ignored in official circles, as have gender, queer and other non-binary identities. Communist regimes have by and large struggled with queer issues just as much as more liberal political systems. By the time the CCP came to power, for instance, homosexuality had been recriminalized in the Soviet Union (where it had briefly been legalized by the Bolsheviks following the 1917 revolution). In the 1920s there was widespread support for gay rights in communist worker movements across the world, but this was largely abandoned following the rise of Stalinism. Maoist China did not specifically outlaw homosexuality, but gay people nevertheless could face severe and potentially crippling persecution.

Very little research has been done on homosexual or queer identities in Maoist China.Footnote 25 Our understanding of those beyond the gender binary is particularly scant: our view of the early PRC remains almost exclusively a cis one. Certainly Mao and his comrades seem to have had no conception that any alternative to binary notions of gender – or indeed to heterosexual identity – might be possible.

In the CCP’s Marxist-Leninist worldview, gender was subordinate to class. Only socialism had the ability to liberate women, and female peasants and workers were therefore expected to ally with their “class brothers” to fight class enemies. The party did criticize male chauvinism among laborers, but equally “bourgeois” feminism was seen as a plot to divide the working class along gender lines. The party-state declared a goal of “equality between men and women” and spoke of a “women’s movement,” but the leadership of the CCP never used “feminism” as a term of praise.

Over time, what it meant to be a man or woman under the CCP began to change. After the founding of the PRC, labor began to be re-divided along traditional gender lines. Party leaders such as Zhou Enlai defined child bearing as the “natural duty” of women, and it was taken for granted by the party and most of society at large that every “normal” person should be expected to marry and have children. When female revolutionary activists, some of whom had fought on the front line in the communist guerrilla forces during the Anti-Japanese War, came back from the revolutionary struggle, many felt that they did not know how to be women or how to (re)integrate into traditional family life.Footnote 26 Military service, however, was no longer open to them, as women were largely excluded from combat units when the PLA’s forces were regularized in the 1940s.Footnote 27

For politically active women there was often pressure to take positions, not as cadres in the regular party organs, but in the All China Women’s Federation or the various task forces working on family planning. This form of women’s work was considered less political than other kinds of activism, and like other mass organizations the Women’s Federation was under the leadership of the CCP and unable to openly contradict party policies. However, women did have some success in using official organizations to champion gender equality, especially when feminist demands could be cloaked in the language of class, making elements of gender contradiction less visible.Footnote 28

In some aspects of its work the CCP actively promoted the voices of women. Particularly in urban China, the party appreciated that female cadres were more likely than men to gain admission to people’s homes, particularly when the visit related to sensitive issues such as the new marriage law or family planning. For local home visits, the party therefore preferred to use female activists. In leadership roles, however, the picture was less rosy. No woman served as a provincial party secretary at any point during the Mao era, nor did any woman ever serve on the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the PRC’s most powerful political institution. Indeed the only woman to become a member of the Politburo at any level during this period was Mao’s wife Jiang Qing, between 1973 and 1976.

A key political role for women during the Mao era was to be one-half of a model “revolutionary couple.” In these couples, usually moving in elite political circles, the husband would generally hold the more senior position, but the wife also contributed to the revolution and the building of socialism. Among the most famous revolutionary couples were Mao and Jiang Qing, President Liu Shaoqi and his wife Wang Guangmei, Premier Zhou Enlai and Deng Yingchao, Minister of Defense Lin Biao and Ye Qun, founder of the Red Army Zhu De and Kang Keqing, and economic planner Li Fuchun and Cai Chang. Kang and Cai both served as chairwoman of the All China Women’s Federation, while Ye was a member of the PLA’s Cultural Revolution Leading Group. In political couples at the local level, a husband might serve as the party secretary while his wife acted as head of the local branch of the Women’s Federation.Footnote 29

After 1949, the CCP’s treatment of “invisible” domestic labor oscillated between extremes. A mid-1950s campaign to honor “socialist housewives,” for instance, was replaced during the Great Leap Forward by plans to “socialize housework” under the auspices of the collective. Exactly what, then, did Mao’s famous maxim that “women may hold up half of the sky” mean in practice? In industry, women do seem to have enjoyed greater opportunities under the CCP. Under the slogan “What men can do, women can do too,” women were permitted to take up jobs such as steel worker, mechanic or tractor driver that had traditionally been a male preserve. Heavy manual labor in the fields also became a less exclusively male job, and women were able to join political meetings. The slogan, however, seems to have been a one-way street. There was no parallel effort from the CCP to encourage men to take up housework, spin cloth or take care of children and the elderly. At least after the socialization of housework was abandoned in rural China, the CCP leadership appears to have been more interested in mobilizing women to boost the “productive” sectors of the economy than in encouraging a fair share of domestic work. It is possible to argue, as some scholars have done, that women fulfilled the function of a reserve labor force, to be mobilized as the party required. Millions of women were recruited into industry at the start of the Great Leap Forward in 1958, only to be demobilized in 1961 when the failure of economic development necessitated a downsizing of the workforce. The well-known campaign to mobilize “iron girls” (tieguniang) into special production teams for heavy labor in agriculture, promoted by the party during the Cultural Revolution, was partly related to a shortage of male labor in this sector.Footnote 30

As with so much in Maoist China, the gendered division of labor differed across the urban/rural divide. In urban work units, domestic labor was socialized to a much higher degree than in the countryside, with state-owned enterprises providing canteens, nurseries and kindergartens. The principle of “equal pay for equal work” was by and large adhered to. In terms of labor force participation, however, women tended to be most numerous in collective enterprises, where jobs were less attractive and secure.

In the countryside, most care work was done by women within the family unit. In Shaanxi and many other provinces prior to 1949, rural women would contribute to the income of the household by weaving and clothes-making, but their markets disappeared after the state monopoly for the sale and purchase of cotton was established in the 1950s. The CCP saw domestic weaving not as a form of manual labor (laodong) but as less valued housework (jiawu), and a permanent shortage of cotton meant that it became a challenge for rural women to clothe the family, let alone sell on the open market. In place of weaving, largely done during night hours under poor light,Footnote 31 the party mobilized rural women to work by day in the fields. Pay, however, was more unequal than in the cities. Adult women would usually receive seven or eight work points a day compared to the ten given to men, with men’s greater physical strength being the most common justification for the difference.

It is important to understand that in the countryside, the family was not only a unit of consumption, but also of production. The semi-socialist order that remained in place after 1962 provided plots for private use for every family. Although their harvest could not be legally sold at market, these plots were important for nourishing the family. The productivity of a family’s private plots and its ability to earn work points in the collective were both related to its ratio of strong, working-age people to children and the elderly. Family structure, particularly in terms of age and the gender balance, therefore had an important impact on income and levels of reliance on the production team.Footnote 32 As a result young and elderly women had different experiences of the social transformations of the early PRC. With the participation of women in manual labor outside the house and in political campaigns, the social control previously exercised by older women over the young weakened. The stereotypical Chinese mother-in-law, lording it over her hapless daughter-in-law, found her power under threat in the Mao era.

Ethnicity

As with gender issues, CCP ideology viewed ethnicity as secondary to class and class struggle. Building on orthodox Marxism-Leninism, Mao emphasized several times that the national question was at its root a class issue. In this reading, the Han chauvinism and local nationalism of the “old society” were both instruments of the ruling class to divide the laboring masses. Suppressed minorities, it followed, could only be liberated in alliance with Han workers and peasants. Socialism was the way to improve their life, and in a future communist society the importance of ethnicity and nation states would ultimately disappear.

The CCP rejected the Republican concept of a single Chinese nation (zhonghua minzu) divided into five races (Han, Manchu, Tibetan, Mongol and Hui). Instead, the PRC was founded as a multi-ethnic state. The concepts of ethnicity (also minzu) and local autonomy articulated by the CCP borrowed heavily from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), but several points of difference from Soviet practice emerged. Whereas Russians comprised less than 50 percent of the Soviet population, the Han made up over 90 percent of the Chinese. No union of republics or ethnic branches of the Communist Party were established in China. In contrast to the USSR, the Chinese constitution guaranteed local autonomy, but included no right of self-determination to declare independence. This reduced autonomy was perhaps related to the strategic importance of the non-Han areas, which cover more than one-third of the PRC’s territory and border India, Burma (now Myanmar), Vietnam, Russia and North Korea.

Today it tends to be taken for granted that China’s population consists of the Han Chinese plus fifty-five ethnic minorities. However, the emergence of the minorities is the result of a complex process stretching back several decades. The PRC began to label its citizens according to ethnic categories in the first half of the 1950s. The identity of large groups like the Han, Tibetans and Mongols was taken for granted, but for the multi-ethnic borderlands such as Yunnan and Guangxi in the south, the government decided to send teams of ethnographers and cadres to determine what classification scheme ought to be adopted. This determination was considered a necessary first step towards defining local autonomous territories and admitting the appropriate number of minority representatives into the People’s Congress. Most of the PRC’s efforts in ethnic classification spanned the years from the early 1950s to 1964. By 1953, the government had recognized thirty-eight groups as “ethnic minorities,” and a further fifteen new groups were added by 1964. After this period, only two new groups would be recognized.Footnote 33

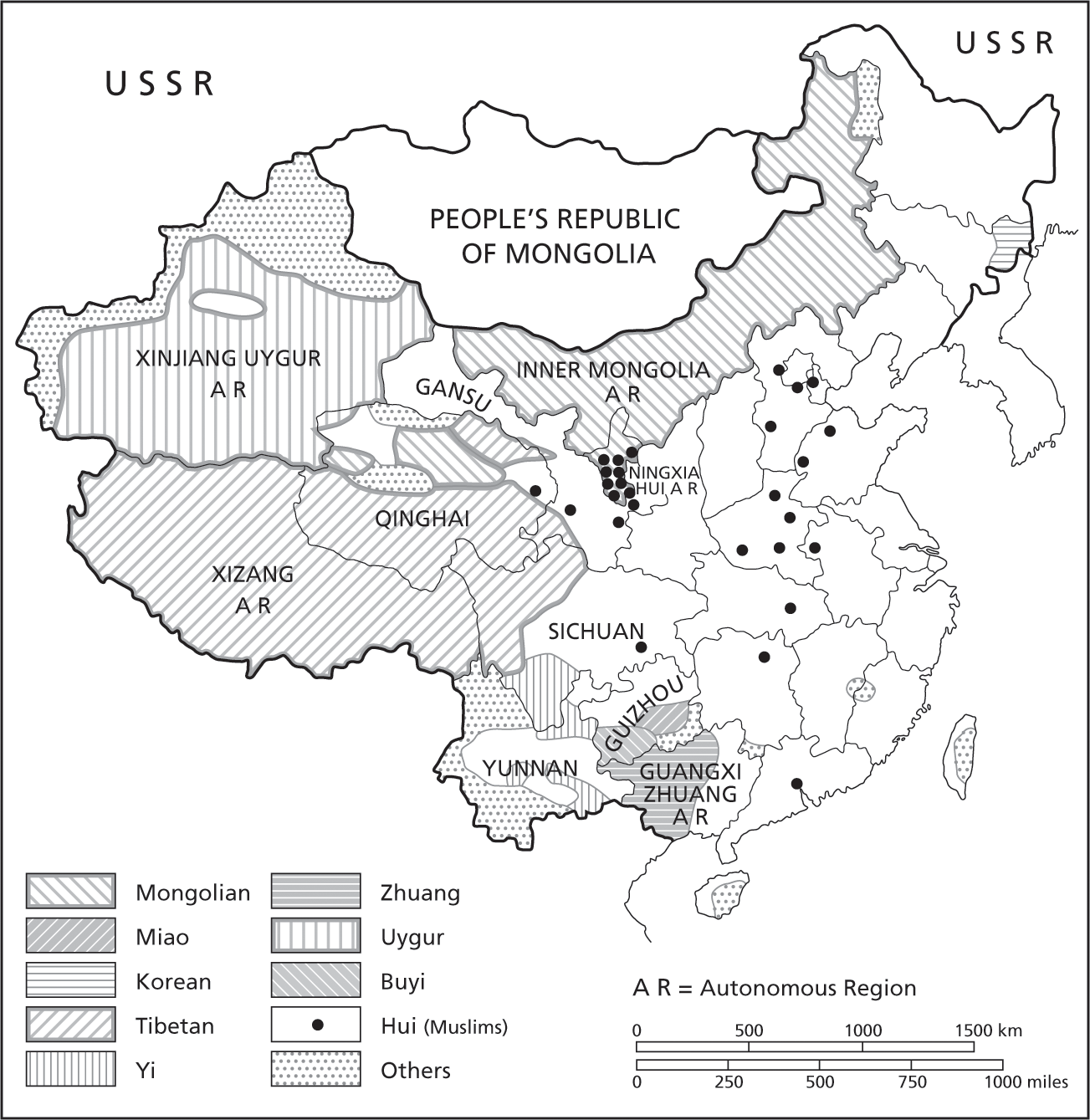

Map 1.1: Major ethnic groups in China

Especially in 1954, this classification was hastily carried out. The Soviet criteria for defining a nationality (common language, territory, economic life and common psychological make up, with tribal communities excluded) proved too complex to adhere to rigorously. As a result, the Chinese investigation teams relied heavily on linguistic criteria to classify nationalities, particularly in the western part of the country.Footnote 34

In contrast to class status and the urban/rural divide, however, classification according to gender and ethnicity caused only minimal conflict. Some ethnic groups did resent being classified inappropriately: a number of communities of “Tibetans,” for instance, considered themselves to be Mongolians, while the largest ethnic minority, the Zhuang, was something of a hodge-podge, encompassing numerous different self-identified groups.Footnote 35 Minor adjustments to the classification system continued after 1979, when the state recognized the last official minority, the Jinuo in Yunnan. In the early 1980s, the state launched a series of investigations into minority groupings in the western provinces, aiming to improve the accuracy of its labeling and to better distinguish between smaller ethnic groups such as the Dong and Miao or the Tujia and Man (see Chapter 8 for more detail).Footnote 36

The PRC’s classification system is premised on the notion that each person belongs to a single, specific ethnic group. It remains impossible in China to register a child as having a dual ethnicity such as “Han-Tibetan” when the parents are from two different groups. Nor is it possible to simply register as “Chinese” (unlike, say, socialist Yugoslavia, where people could eschew labels such as “Croatian” or “Serb” and register simply as “Yugoslavian”). Since the 1950s, China’s ethnic categorization system has been the foundation for affirmative action in higher education and for the training of minority cadres. It is the stated belief of the CCP that the GMD discriminated against minorities and that the Han’s “little brothers and sisters” needed support to develop after 1949.

The vast majority of minorities lived in poor, rural areas or in the western provinces as peasants and nomads. Most were therefore excluded from the state-subsidized urban economy. Moreover, the CCP considered minorities as generally more “backward” than the Han Chinese. The official party theory of historical materialism held that the history of mankind was marked by development through several stages, from primitive society through slavery, feudalism, capitalism and finally socialism. The minorities, the party asserted, were by and large still mired in slavery or feudalism, whereas the Han, had progressed to a “semi-feudal” society before 1949.

This perceived backwardness meant that minority regions would need more time to enforce the social change the party demanded. In Tibet and Mongolia, the CCP promoted a United Front with “patriotic” local elites in the early 1950s, leaving class labeling for a later period. Minority cultures and religions were always officially supported by the state. However, the relatively tolerant and gradualist approach of the early 1950s gave way to more assimilationist policies during the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution. The United Front’s work with the upper stratum of the minorities was replaced with a new program of class struggle. In language policy, the government from the 1950s onwards supported programs to create a written language in some previously oral minority communities. Existing scripts and terms were reformed to create languages that better fitted the necessities of modernization and the ideology of the CCP – Tibetan is a particularly well documented case. The top-down nature of these reforms is emphasized by the fact that most cadres in the minority areas were Han Chinese from other regions. By and large, these representatives of the state could not speak or understand local languages before arriving, and some made no effort to learn.

Although the fifty-six recognized ethnic groups had nominally equal standing, in practice a hierarchical binary existed, with minorities on one side and the Han on the other.Footnote 37 For the minorities, ethnic labels played a central role in everyday relations with the state, while for the Han ethnic status was important mainly as a mark of distinction against a minority “other.” The Han had no special representatives in the People’s Congress, and it was taken for granted that the leaders of the party-state, almost all Han, were well equipped to represent the interests of the Chinese nation as a whole and even to lead “autonomous” minority areas. No Tibetan ever served as the first party secretary of the Tibetan Autonomous Region, while one Uygur, Seypidin Azizi, served in the same position in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The CCP promoted the education of minority cadres, but only a few, such as the ethnic Mongol Wulanfu (Ulanhu in Mongolian), a party member since 1925, were considered reliable enough to serve in leading positions (in Wulanfu’s case as a vice-premier and alternate member of the Politburo).

Little research has been done on the question of how ethnicity and class status interacted with gender during the Mao era. There was clearly considerable crossover. In Tibet, for instance, the CCP used “Liberation of Women” as a slogan to promote class struggle. Poor rural women, whose status in their own communities was low, were recruited to work on state farms in the 1950s, becoming part of the state project to build a new Tibet.Footnote 38 In state media and films, meanwhile, exotic images of minority women in colorful ethnic costumes were already a staple. It seems to me that both the state and the Han majority viewed minorities in primarily ethnic terms, but issues of gender and class clearly cannot be overlooked.

Classification, Files and Registration

Classifying the population was a great bureaucratic challenge for the state. In the early PRC, every family had a household registration document, but identity cards (shenfenzheng) were issued only in the Reform era after 1984. The other most common identity document, the passport, was available only to the very few who were allowed to travel abroad as diplomats or students or to attend conferences. Every such trip had to be approved by the work unit or even by higher levels of government.

“Inside the system,” members of work units had a personal file (dang’an). To enter a work unit, the party or mass organizations, people had to complete forms covering family origin, individual status, gender, ethnicity and so on, and the unit could check these against the official record. Providing false or misleading information could lead to serious consequences if, for example, a “landlord who had escaped the net” was uncovered. Dang’an files included evaluations of political performance by superiors or party secretaries, as well as documents related to any “historical problems,” and a separate system of individual files, containing similar information, existed for CCP cadres.

During political campaigns, files were often rechecked to uncover hidden enemies. Individuals, however, had no right to access their own files, and therefore no way of knowing for certain how their superiors had evaluated them. In the early Cultural Revolution, control over personal files became a major source of conflict. Red Guards occupied archives to get access to the files of cadres, seeking to edit “black material” and attack them. Some Red Guards who had faced repression themselves demanded the deletion of negative information.

Prior to 1963, ordinary peasants had no personal files. During the Socialist Education Campaign, however, the Central Committee began creating class files for rural families.Footnote 39 Some forms included the class status of the head of the household, but in general the family, not the individual, was the main unit of analysis. The creation of these rural files was designed to allow the reinvestigation of class status and also the addition of new information about the “performance” of people during campaigns, along with any rewards or punishments received. Document 1.1, a family registration form from 1966, provides a good example. It draws a clear line between personal status and family origin. The lead householder and his wife were of “middle peasant” and “poor peasant” background, but both were assigned the personal status of “urban poor.” Their personal history is also recorded, although the form provides a cautionary tale of how an apparently incorrect class status might be given even with an abundance of information available. The form notes that the husband, Wang Yinquan, sold vinegar in several cities until 1963, while his wife and children stayed in their home village to farm their land. By the time the document was written in 1966, however, the husband had returned to the rural commune and retired. The label of “urban poor” reflected his personal history, not his current situation.

Wang’s past as a petty trader might have exposed him to suspicion. However, his political performance was evaluated favorably. His son, Wang Shuangbao, was a member of Communist Youth League, had served in the PLA and was educated to junior high school level. The younger Wang’s status, too, seems to have been rather haphazardly determined. He was listed as a student despite a “current occupation” as a soldier. His family origin of “middle peasant,” meanwhile, was apparently taken from his grandfather, in defiance of official regulations requiring that family origin was to be inherited from the father (whose rank, as we have seen, was “urban poor”). Local actors, the form suggests, often did not classify according to central standards. The creation of rural class files was also not universally enforced, with many ordinary rural people remaining essentially undocumented, at least in terms of class. However, in many villages, close family ties and a lack of social mobility or out-migration after 1962 meant that any bad class labels assigned during Land Reform were likely to be common knowledge.

Informal Channels of Distribution

Clearly official labels, and the distribution system for goods and services that they supported, were an important part of the Maoist economic system. However, this system faced a serious, unresolved problem: it could not satisfy the needs of people. During the famine of 1959–1961, not even survival was guaranteed in the countryside. Much of the population, but peasants especially, learned the hard way that they could not rely on the state.

In urban areas, the basic needs of the population were met in all except the famine years. If, however, an individual needed more than basic goods, he or she had to find alternative ways of acquiring them. In the GDR, this working around the system was referred to ironically as the “socialist way.” While personal relations play a certain role in distributing goods or jobs in all societies, people in socialist states were particularly skillful at navigating the informal distribution of public goods. Because self-interest and critiques of the system could not be openly expressed, much of this informal distribution happened below the surface. As the Chinese expression puts it: “Policy above meets counter-policy below.”

In the countryside, theft of grain and “concealing production to distribute privately” (manchan sifen) became widespread almost as soon as the collectivization of agriculture began in the mid-1950s. During the famine, many peasants “ate green” (chiqing), surviving on unripe crops taken from the field before the harvest. This and other practices for under-reporting production or land usually had to be covered up by cadres in the production team. These cadres, however, were not on the state payroll and often had relatives in the villages, making them potentially receptive allies. The Chinese scholar Gao Wangling calls these strategies “counter-actions” that were not meant to be resistance against the state, but survival strategies.Footnote 40 This is true from a peasant perspective, but theft and under-reporting did affect the state’s policymaking, reducing the amount that could be taken to feed the cities or for exports.

Peasants could try to get access to the urban rationing system through “blind migration” into the cities. This was relatively easy before 1961 but became challenging during the rest of the Mao era, when the household registration system was strictly enforced. In the cities, workers had fewer reasons to steal food or try to move away, and strike action over wages occurred on a large scale only before 1958 and during the early Cultural Revolution. Many workers and peasants did, however, try to reduce the workload that the cadres demanded. In socialist countries in Eastern Europe, people would say of the government that “they are pretending to pay us and we are pretending to work.” The Chinese equivalent was moyanggong, “feigning work.” One particular popular method was to shop for groceries – often requiring hours of queuing – during the working day.

Another widespread practice during the Mao era was “entering through the backdoor” (zouhoumen). This was a form of cronyism whereby a person would gain access to goods or a job thanks to personal connections to officials. During the supply shortages of the Great Leap in 1959, individuals would use this strategy to get much-needed food. Organizations could also “enter through the back door,” with work units tapping official connections to secure materials needed to fulfill their production quotas.Footnote 41 During the Cultural Revolution, “sent-down youths” seeking a way out of the countryside sometimes used the same tactic to enlist in the PLA or enroll as students (for more detail see Chapter 7). The CCP leadership criticized this informal practice many times, fearful of undermining the image of social justice and fair distribution. However, scarcity of resources, combined with the personal power of cadres to ignore formal rules, ensured “entering through the backdoor” never disappeared.

What exactly was the relationship of these practices to official power? There is no justification for glorifying all forms of informal distribution, as some have done, as “weapons of the weak.”Footnote 42 It was not only the weak who gained access to goods they were not entitled to, but also the powerful. Moreover it was CCP cadres, not ordinary peasants, who were in the best position to defraud the state. These cadres, as we have seen, were predominantly male and predominantly Han. The more powerful and senior of these cadres also tended to be older, drawn from the “revolutionary cadres” of the pre-1949 days. Unlike today, cadres could not transfer millions of US dollars to foreign bank accounts, but the archives of the anti-corruption campaigns of the Mao era include impressive accounts of fraudulent and illegitimate activities for capturing food and finances. During the famine, many rural cadres took advantage of special canteens to ensure that they remained well fed while others starved. For those outside the CCP’s protective umbrella, having a relative working as a cook in a public dining hall might be the difference between life and death.

Based on a case study in Anhui province, one scholar argues that survival in the villages during the famine was often decided by the strength of kin relationships.Footnote 43 Some observers suggest that personal relationships (guanxi) and the exchange of gifts and favors (renqing) helped ordinary people, both men and women, to receive goods through informal means. Other scholars, by contrast, claim that these systems were most profitable to powerful men.Footnote 44 More research is required before any definitive answer can be reached.

The Role of Internal Migration

Internal migration played a crucial role in both upward and downward social mobility and the remaking of territorial space in the Mao-era PRC. As we will see, state-organized and self-directed migration were often connected to the major state classifications (household registration, class status, gender and ethnicity). One of the most pressing questions of the Mao era was who was to be allowed to stay in the cities and enjoy the entitlements of the “iron rice bowl.” Following the large-scale demobilization of soldiers in the early 1950s, for instance, many veterans sought permanent employment in the cities. The central government’s insistence that they return to their home villages caused considerable frustration, with many questioning why their sacrifices for the nation did not entitle them to better treatment. Some veterans simply moved to an urban center without authorization (“blind migration”), while others protested openly.Footnote 45

The main destination for internal migration was the northern provinces of Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Ningxia, Qinghai and Heilongjiang. Between 1952 and 1982, the population of some of these regions doubled, far outstripping the nationwide increase of 50 percent in the same period. Much of this migration consisted of Han Chinese moving into the ethnic minority Autonomous Regions.Footnote 46 The government supported this development to “open up” underdeveloped borderlands and establish firmer control over the periphery: in Xinjiang and Tibet, two particular trouble spots, migration was encouraged by establishing a network of military farms.

Some Han Chinese migrated to the border regions voluntarily, either out of patriotism or poverty. Soldiers and cadres, meanwhile, could be ordered to go. These overwhelmingly male settlers and military personnel were supported by a government-organized “supply” of Han Chinese women from Inner China. Criminals and enemies of the regime were also sent to the western periphery: according to the official numbers, over 123,200 “criminals” from all over the country were sent to the labor camps and farms in Xinjiang in the 1950s.Footnote 47

In contrast to Stalin’s Soviet Union in the 1930s and 1940s, the Chinese government did not enforce policies to compel “unreliable” ethnic groups from the border regions to resettle in the hinterland. Nor did China experience the ethnic cleansing seen in other parts of the world. In some regions such as Xinjiang, however, government policy seems to have been designed to ensure Han Chinese would outnumber local ethnic groups (see Chapter 2). The ratio of Han Chinese to Mongolians in Inner Mongolia, for example, increased from 6:1 to 12:1 between 1958 and 1968.Footnote 48

The first major movement of population under Mao was a rapid wave of rural-urban migration. Spanning the years 1949 to 1960, this process saw large numbers of rural Chinese attempt to break into booming new industries in the cities. The earliest state-organized migration, meanwhile, was the sending of cadres from the “old liberated areas” of the north to “go down south” with the advancing PLA in 1949. The goal was to establish control in the “newly liberated areas,” where activists and party members were few. Incomplete statistics suggest that over 130,000 cadres were sent out, while 400,000 family members also went south with the army.Footnote 49 These people often struggled to communicate with local rural communities due to language differences. Between 1952 and 1958, more than 379,000 migrants, mainly from Shandong, went to Heilongjiang in the far north to open up uncultivated land or to work in industry. Major infrastructure projects such as the construction of reservoirs and hydroelectric power plants led to the displacement of about 5.68 million people in the first three decades of the PRC.Footnote 50

The Great Leap Forward also led to a massive wave of rural-urban migration in 1958. This was partly uncontrolled and unwanted by central authorities, partly a result of labor recruitment by work units to meet their ambitious new targets. During the famine, millions tried to escape to less badly affected regions, some to nearby provinces and counties, and others to Xinjiang or the north-east. In order to stabilize the economy and the distribution system in aftermath of the famine, the government sent over 26 million people from cities and towns to the countryside between late 1960 and 1963.Footnote 51 Between 1963 and the early 1970s, millions of workers, along with equipment, resources and factories, were transferred from the east coast to western China in order to build the so-called “Third Front,” designed to minimize industrial losses in the event of an attack on the coastal cities. In 1966, during the early Cultural Revolution, hundreds of thousands of people with a bad class status were deported from the cities and forced to settle in the countryside. Red Guards organized these deportations with the support of Public Security Departments in order to “cleanse” the cities of “non-proletarian elements.” According to official statistics, between July and October of 1966, 397,400 “ox ghosts and snake demons,” as these people were called, were deported from cities across the country.Footnote 52 Starting from late 1968, the government intensified its program of sending “urban youths” down to the countryside. Over the course of the Cultural Revolution, in excess of 16 million people were “sent down” in this way.Footnote 53

These numbers suggest it would be wrong to imagine Maoist China as a society with a static population. The factors underlying internal migration in the PRC, however, owed less to economics than to state policies. The state’s motives in instigating these migrations, and the popular responses to them, form a crucial part of the narrative of Maoist China. These and other social changes, and the classifications and conflicts that went with them, will be discussed in more detail in the following chapters.

Document 1.1 Class status registration form (1966).

First production team, Dingxing zhuang production brigade, Dong Village commune, Xin County, Shaanxi Province

| Name of householder | Gender | Male | Family Origin | Middle peasant | Family size | Population at home | 3 |

| Age | 63 | ||||||

| Wang Yinquan | Nationality | Han | Personal status | Urban poor | Population outside home | 1 | |

| Family economic conditions | During Land Reform | Before Land Reform, the household made vinegar in the towns. They could hardly make a living and went back home after Land Reform (in 1948 and 1949). They made a living afterwards with three rooms and eight mu of land that their elderly parents gave to them. | |||||

| During the advanced cooperative | During the advanced cooperative, the household possessed eight mu of land and three rooms. Nothing else. | ||||||

| At present | The household currently possesses three rooms and eight fen of plots for private use. Nothing else. | ||||||

| Major family social relations and their political appearance |

| ||||||

| Description of family history |

| ||||||

| Remarks | |||||||

Profile of family members

| Name | Wang Yinquan | Sun Hua | Wang Shuangbao |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relation to head of household | Head of household | Wife | Son |

| Sex | Male | Female | Male |

| Age | 63 | 52 | 22 |

| Nationality | Han | Han | Han |

| Family origin | Middle peasant | Poor peasant | Middle peasant |

| Personal status | Urban poor | Urban poor | Student |

| Education | Primary school | Illiterate | Junior high school |

| Religion | No | No | No |

| Commune member | Yes | Yes | No |

| Current occupation and duty | Commune member | Commune member | Soldier |

| Member of revolutionary organizations | None | None | Communist Youth League |

| Member of reactionary organizations | None | None | None |

| Rewards and punishments | Rewarded for making vinegar after liberation | None | Five-good soldier |

| Main experiences and political performance | At the age of 18, he went out and made vinegar till the age of 45. He made vinegar again from age 47 to 60. His political performance is very progressive. |

|