Book contents

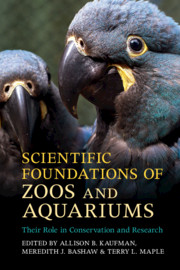

- Scientific Foundations of Zoos and Aquariums

- Scientific Foundations of Zoos and Aquariums

- Copyright page

- In Memoriam

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Programs and Initiatives

- Part II Captive Care and Management

- 7 Lear’s Macaw (Anodorhynchus leari) Ex Situ Breeding Program at São Paulo Zoo

- 8 Measuring Welfare through Behavioral Observation and Adjusting It with Dynamic Environments

- 9 Empowering Zoo Animals

- 10 Transforming the Nutrition of Zoo Primates (or How We Became Known as Loris Man and That Evil Banana Woman)

- 11 Tough Questions, Complex Answers

- Part III Saving Species

- Part IV Basic Research

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Index

- References

10 - Transforming the Nutrition of Zoo Primates (or How We Became Known as Loris Man and That Evil Banana Woman)

from Part II - Captive Care and Management

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 December 2018

- Scientific Foundations of Zoos and Aquariums

- Scientific Foundations of Zoos and Aquariums

- Copyright page

- In Memoriam

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Programs and Initiatives

- Part II Captive Care and Management

- 7 Lear’s Macaw (Anodorhynchus leari) Ex Situ Breeding Program at São Paulo Zoo

- 8 Measuring Welfare through Behavioral Observation and Adjusting It with Dynamic Environments

- 9 Empowering Zoo Animals

- 10 Transforming the Nutrition of Zoo Primates (or How We Became Known as Loris Man and That Evil Banana Woman)

- 11 Tough Questions, Complex Answers

- Part III Saving Species

- Part IV Basic Research

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Scientific Foundations of Zoos and AquariumsTheir Role in Conservation and Research, pp. 274 - 303Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019

References

- 1

- Cited by