What he has achieved was not only to the benefit of a national American music, but also a contribution to the music of the whole world.

After their long train ride from New York through Chicago and across the West, Arnold, Gertrud, and Nuria Schoenberg arrived at the Pasadena Train Station in mid September in 1934 and headed for a hotel. They found a room at the Hotel Constance, a seven-story structure on Colorado Boulevard in downtown Pasadena. The building was still standing into the twenty-first century, rising in neo-Italian Renaissance splendor, towering above everything around it. Built in 1928 near the end of the resort era, it belonged to the legacy of Pasadena's Eastern, health-seeker past.1 Perhaps the hotel's name reminded the Schoenbergs of the Europe they left behind. Within two weeks of their arrival, a friend from Vienna with whom Schoenberg had played string quartets in their youth, film composer Hugo Riesenfeld, found a furnished house at 5860 Canyon Cove that they could rent in his neighborhood in the Hollywood Hills, a little over two miles north of Paramount Pictures. They settled in, and obtained a car (see Figure 2.1). For the next 1½ years of the Schoenbergs’ life in California, Hollywood was their home.2

Figure 2.1 Arnold, Gertrud, and Nuria Schoenberg in front of their La Salle automobile, c. 1934.

Few institutions held a fascination for the exiles like Hollywood. In scholarship on the exiles, perhaps no other single institution in the West has garnered as much attention.3 “Arnold Schönberg and Igor Stravinsky,” wrote contemporary composer/conductor René Leibowitz, “the two most important composers of today…have settled down in Hollywood, which is about as far as a European can ‘go West.’”4 Although almost all seemed to hold it in contempt, many exiles nonetheless saw the entertainment industry as a lifeline during the Great Depression. One of the few places in the United States in the 1930s where American- and foreign-born artists had a chance of doing exceedingly well, Hollywood was also a rare site of religious toleration: a city where Jews and Gentiles intermingled relatively freely.5 The multiple advantages of living near Hollywood intrigued Schoenberg, and while he hardly had plans of becoming a serious film composer, he hoped to profit from the film industry in another way: by teaching music theory and composition to musicians in Hollywood. The film industry thus became an early and important source of income and connections, where he found not only students but also friends and colleagues.

This means that we should be careful in creating borders between classical and popular music, and between classical and popular musicians, in Southern California. Such borders increasingly had less of a place in the diversified environment of modern music in the region. Out of necessity, many art music composers used the film industry to support themselves and their families, which thus enabled them to do the art music projects or compositions they wanted to achieve. Although Schoenberg never completed a film score for a studio, it is impossible to discuss his life and work in Southern California without reference to Hollywood, either in terms of the works he created or the people with whom he associated. On a level perhaps even he would have been astounded at prior to his immigration, Schoenberg maintained ties to Hollywood until the end of his life.

Like many of the exiles, Schoenberg had a strong interest in the medium of film well before he immigrated to the United States. When talking pictures first appeared in 1927, he wrote on the power and potential of film as a means of communication, pointing to one of his idols, Charlie Chaplin, as an example of what filmmakers could, and should, achieve. “One should not consider the talking film to be simply a coupling of picture, language, and music,” he declared. “On the contrary, it is a completely new and independent instrument for innovative artistic expression.” The future was bright, he wrote, because “the application of overall standards will become the rule, standards that up to now could only be reached by exceptionally gifted personalities like Chaplin.”6

How did Schoenberg, the preeminent modernist composer, hope to achieve his goals in Hollywood? What network of students and colleagues in the entertainment world did he benefit from? And how did the presence of other émigré composers in Hollywood – among them Igor Stravinsky, Ernst Toch, and Hanns Eisler – shape modernism in Southern California? The film industry proved to be a major factor in enticing Schoenberg to the West Coast, although he insisted on meeting that industry on his own terms.

Hollywood

Look at a map of the city of Los Angeles. At its geographic center is not downtown, which is to the east, but Hollywood. Sprawling across the Santa Monica Mountains to the north and flat ground to the south, Hollywood in the 1930s was a prime example of Los Angeles's startling growth. From about 700 residents in 1903, when Hollywood was incorporated, its population grew to over 185,000 thirty years later. Crowded, bustling, and wealthy, by 1937 construction projects in Hollywood reached $56 million, more than any other city in the United States except New York and the city of Los Angeles itself.7 It was the era of the Great Depression, but it was hard to see it in Hollywood.

The Hollywood Hills, where the Schoenbergs lived, overlooked the descent to the Pacific Ocean 12 miles below. The Santa Monica Mountains separate the San Fernando Valley to the north and the Cahuenga Valley to the southeast; this location had long made the site attractive for settlement at least as early as the Tongva Indians, because the mountains protect against hot desert winds that come from the north, while harboring cool ocean breezes coming up from the south. Before World War II a rural sensibility still lingered, and flowered gardens and fruit orchards abounded. Adding to a Mediterranean-like environment were the small, white stucco houses and bungalows that dotted the hillside. In stark contrast, straddling the hills was the “Hollywoodland” sign, in deteriorating condition in the 1930s but still glowing at night with 4,000 light bulbs.8 When the Schoenbergs stepped out on their front porch, they knew they were a long way from New York and seemingly an eternity from Berlin.

Before it became the world center for the film industry, Hollywood was at its roots a deeply religious site. Its original founders, Harvey and Daieda Wilcox from Kansas, offered free lots in the 1880s to anyone who would build a church. Even in the 1930s there were far more churches than studios; almost seventy churches were still standing when the Schoenbergs arrived. Religious fervor was diverse and eclectic; the Hollywood Hills had long beckoned free thinkers, religious zealots, and artists alike. Only a few blocks west from where the Schoenbergs lived was the site of the former Krotona colony at Vista del Mar, an outpost of the Theosophical Society, where plays, concerts, and lectures regularly took place. In the 1920s, theosophist and composer Dane Rudhyar was drawn to this community, and he became a devoted admirer of the city's semi-rural existence.

Several religious-themed events drew thousands of people each year. From 1920 to 1951, the outdoor Pilgrimage Play, for which Rudhyar was commissioned to write a musical score, regularly depicted the life and crucifixion of Christ.9 Across the street from the theater was the Hollywood Bowl, where the Easter Sunrise Service began in 1922 and soon attracted a larger audience than almost any other annual event in Los Angeles – up to 50,000 people.10 To make the connection between Hollywood and Christianity clear, a large white cross, which still stands prominently on a hill, looked down on the theaters below. This was “holy land,” and performances at these venues were as far apart in sensibility from the grind of the film studios as cornfields in Kansas.

The studios reigned supreme, however. By 1920, the film industry had become one of the largest industries in Los Angeles, and six years later it was the fourth largest industry in the world in terms of net profits.11 During the 1930s, over twenty million Americans went to the cinema, or about a tenth of the country's population. The studios were in their Golden Era (about 1915 to 1945), making over 75 percent of all the films in the world, and 90 percent of all American films. With only one studio in 1911, there were nineteen studios by 1925, although by the 1930s these had been consolidated to the “Big Eight,” and of those only a handful were actually within the city boundaries of Hollywood itself. Schoenberg would eventually have contact with four of them: MGM, United Artists, Twentieth Century-Fox, and RKO Pictures.12 Hollywood had long since become a metaphor, a symbol of entertainment, and that symbol drew aspiring entertainers like moths to a flame. Musicians, actors, directors, writers – a vast creative pool migrated to the West Coast, longing for their place in the sun in a kind of second Gold Rush. With the onset of the Great Depression, the rush to Hollywood grew to a stampede, since few other places in the country allowed artists to make as much income in the 1930s. In seeking to apply their artistic talents for potentially lucrative contracts, the exiles were no different from anyone else.

Contacts

When the Schoenbergs first arrived in Southern California, they knew scarcely more than four people – composer Hugo Riesenfeld, composer Adolph Weiss, screenwriter Salka Viertel, and conductor Otto Klemperer – and three of them had connections to Hollywood. Riesenfeld studied composition with Schoenberg in Vienna in the early 1900s and played chamber music with him before immigrating to the United States in 1907 to work on musicals for Oscar Hammerstein.13 One of the earliest German émigrés in the film industry, he moved to Hollywood during World War I and then became musical director for United Artists after its creation shortly after the war. This proved to be an excellent opportunity for Riesenfeld to hone his craft of film music, and he became a pioneer in composing for silent films before transitioning readily to sound pictures in the late 1920s. As an indication of his success, he had a prominent home in the Hollywood Hills.14

Like Riesenfeld, Weiss was a former student of Schoenberg's and had become one of his foremost American proponents. Born in Baltimore, he had already played in the New York Philharmonic as an 18-year-old bassoonist before becoming one of the few Americans who studied in Schoenberg's Master Class at the Prussian Academy of the Arts in Berlin.15 After his studies with Schoenberg he returned to New York, where he taught John Cage, and then moved to Los Angeles around the same time as Schoenberg. Roughly the same height as his mentor, with dark, wavy hair, he found work as a woodwind player in the orchestra of Twentieth Century-Fox while continuing to compose serious music on the side. One critic, Paul Rosenfeld, described Weiss's music rather unsympathetically as consisting of “chromatic material [that] is not strictly autonomous, and [that] has a strong family likeness to that of Berg, Webern and the rest of the Viennese coterie.”16 As Schoenberg's only American friend in Southern California in the first months of the exile's arrival, Weiss became a frequent guest at the Schoenberg home and later the sponsor (godparent) of two of his children.17

By contrast, Salka Viertel was a vivacious exile who had a close friendship with Greta Garbo. Viertel had first met Schoenberg in Berlin through her brother Eduard Steuermann, a leading interpreter of Schoenberg's music. The wife of writer Berthold Viertel, she arrived with her family in Los Angeles in 1928 and soon came into contact with impresario Merle Armitage and architect Richard Neutra, among other likeminded artists, cultural figures, and actors. Originally an actress herself, Viertel had become a screenwriter on the suggestion of her friend, Garbo, who was on contract with MGM, and she followed Garbo to Hollywood to write screenplays for her, notably Queen Christina (1933), Anna Karenina (1935), and Two-Faced Woman (1941). Viertel was a magnet for the exiles, and her home in Santa Monica was a salon to welcome refugees from Europe, representing what Bahr calls “the importance of Weimar culture in Los Angeles.”18 She immediately began introducing the Schoenbergs to her wide network of friends.

The only figure in this group who did not have a direct connection to Hollywood was conductor Otto Klemperer, who had taken the reins of the Los Angeles Philharmonic the year before Schoenberg arrived. A giant physically and figuratively, the 6′ 7″ conductor towered over the 5′ 3″ Schoenberg, who hoped Klemperer would continue to be a promoter of his music.19 Like Viertel and Weiss, Klemperer had met Schoenberg in Berlin, and also had become an exile like Schoenberg from Nazi Germany. Having lost his position as music director of Berlin's Kroll Opera, Klemperer was traveling in Italy when an agent representing the Los Angeles Philharmonic discovered he had no job. She immediately offered him the orchestra's then vacant position of conductor. Desperate for work, he agreed, arriving in 1933 as one of the first exiled artists with an international reputation. Although the previous conductor, Artur Rodzinski (1892–1958), was a superb musician and effective music director, the orchestra had never quite had someone of the renown of Klemperer. He quickly set about making the orchestra a more distinguished ensemble with his command of the symphonic repertoire and ability to communicate his aims effectively. A recording of a piece by Johann Strauss Jr., Die Fledermaus, which the orchestra made with Klemperer in 1945, is indicative of their work together.20

Unfortunately, the relationship between Klemperer and Schoenberg became increasingly strained. Schoenberg had refused to attend a banquet in 1934 in honor of Klemperer as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, because he felt wronged in the invitation; as Schoenberg wrote to him haughtily, “I consider it unspeakable that these people [who govern the orchestra], who have been suppressing my works in this part of the world for the last 25 years, now want to use me as a decoration.”21 Nonetheless, other than Stokowski, Klemperer was one of the only conductors in the United States who could claim to have premiered several of Schoenberg's works. These included at least two pieces written in Los Angeles: the Suite for String Orchestra, and Schoenberg's arrangement for string orchestra of the Brahms's Piano Quartet No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 25, both of which Klemperer premiered in 1935 and 1938, respectively.22 The financial straits of the orchestra during the Depression severely limited its ability to perform contemporary works, however, which meant largely keeping to music in the public domain. Nonetheless, Klemperer had supported Schoenberg in the past and tried to do so in exile. Unfortunately, he apparently told Schoenberg in 1940 that his music had become foreign to him, for which Schoenberg never forgave him.23

Pauline Alderman and Julia Howell

Although social contacts certainly helped him to habituate to the region, one of Schoenberg's immediate needs was income, and that income came first from private students. Soon after arriving in Hollywood, Schoenberg placed an ad in local newspapers advertising his services. Surely there were talented, eager students with funds, he reasoned, who would like to study with a world-renowned composer and theorist? One of the first people to respond to the ads came not from the film studios but from the faculty at the University of Southern California (USC). Pauline Alderman had been at the USC music department for only four years, joining the faculty with the onset of the Depression in 1930. She wrote that she was stunned to see a newspaper ad in the fall of 1934 stating simply: “The distinguished composer, Arnold Schoenberg, has moved with his family to Hollywood and is accepting students.”24 That Schoenberg was living in Los Angeles seemed too good an opportunity to pass up, and Alderman became one of several students to sign up quickly for lessons.

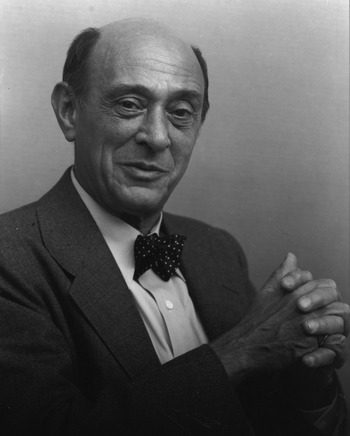

In her first meeting with the composer, she later claimed to being struck above all by Schoenberg's eyes. They were “large, very bright, piercing, but not intimidating.”25 He was short and stocky, she recalled, but seemed younger than his 60 years. Above all, he wanted to hear her opinions on American music education, and especially on college and university music departments in the area. She told him what she knew, equally eager to talk with this legendary figure, until they alighted on the subject of her visit: to give her lessons in composition and theory. Quick to recognize the financial possibilities, he suggested she bring together a group of three or four students who could pool their resources to pay his fee of $200 for the entire group for a set of five lessons.

The composition of the group still remains something of a mystery. We know that Alderman persuaded USC colleague and organist Julia Howell to join her. Howell specialized in music theory as an associate professor in the music department and unlike Alderman was a longtime member of the faculty; she was hired in 1920 and eventually rose to become head of the music theory division for twenty-eight years.26 Estimates of exactly how many students there were in the group varied from four to ten, but we are far clearer on what they studied. They began with Beethoven's 32 Variations in C Minor for piano, followed by Brahms's Third and Fourth symphonies.27 Schoenberg's dedication to the old masters was at the foundation of his teaching in Europe and remained so through all of his teaching in the United States.

One essential aspect of Schoenberg's pedagogy was his analysis of what he called “musical logic.” It was not enough merely to examine harmonic progressions; one searched rather for the very essence of each piece. As he later wrote in a textbook for American students, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, every piece has a logic that is inherent to the work. “The chief requirements for the creation of a comprehensible form are logic and coherence,” he argued.28 That internal logic was also central to his unfinished text, Der musikalische Gedanke (The Musical Idea), which he began writing in 1923 and continued to work on in exile, which we will discuss in the following chapter. “The possibility of connecting tones to one another,” he argued, “is based on the fact that they are related to one another.” Within this relation is the idea of a Gestalt, or motive, which is at the center of all forms of music. “In this way,” he emphasized, “the smallest musical gestalt fulfills the laws of coherence: the motive, the greatest common denominator of all musical phenomena.”29 It seems that he analyzed music as a kind of journey of discovery: to allow students to grasp how a composer created a work, and how that composer developed themes and motives to make the piece an integral whole. In essence, Schoenberg “played musical Sherlock Holmes,” Alderman explained, “to four voracious Dr. Watsons.”30

The first clear indication of Schoenberg's reception in Southern California arose out of this private course. After three months of study, Schoenberg suggested in February 1935 that Alderman organize a larger class, and once again she and Howell drew on their wide network in Los Angeles. The result is that twenty-five musicians crowded into the Schoenbergs’ cramped living room in the Hollywood Hills. One of the most advanced students of this group was a pianist of astonishing skill, Olga Steeb, who had studied in Berlin from 1909 to 1915 before returning to Los Angeles to open her own piano academy on Wilshire Boulevard. Of the twenty music schools in the city, hers was one of the largest, with its own building, studios, and an auditorium.31 During her studies in Germany she must have come across Schoenberg's music and perhaps even his pioneering treatise on music theory, Harmonielehre (Theory of Harmony), first published in 1911; now she finally had the opportunity to study with him in person. The group also included several students who would later achieve distinction in composition, among them Leslie Clausen, Simon Carfagno, and Edmund Cykler.32

One of the works Schoenberg focused on was Bach's The Art of Fugue. While none of his lecture notes have surfaced from this period, at the end of his life he wrote an essay on Bach that gives us some indication of his views of the work. “I have always thought highly of the teacher Bach,” he wrote, because “he possessed a profound insight into the hidden mysteries of tone-relations.” Of particular interest to Schoenberg was Bach's ability “to build in contradiction to the advice of theorists, on a broken chord, all the different themes of the Art of Fugue,” thereby yielding an astonishing inventiveness and skill. Indeed, it represented the culmination of a life's work, even if it remained unfinished at Bach's death.33 Since Schoenberg often wrote fugues and canons, the example of Bach was critical to his identity as a teacher and composer.

The first instance we know of when Schoenberg analyzed one of his own works in Southern California also occurred during this course. Although he rarely taught his own music in class, an analysis of a modern work seemed to balance well with Bach. He agreed to explore his Third String Quartet with them, written in 1927 on a commission by American philanthropist Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge. The twelve-tone piece is in four movements, which draws on a motive that Schoenberg claimed arose from a nightmare of a ship captain “nailed to the mast through his forehead by the mutinous sailors.”34 The culmination of the students learning about a modern piece was a live performance; a local ensemble, the Abas Quartet, performed the quartet at the end of the course, one of the first occasions it was performed publicly in Los Angeles.35

There was a problem in analyzing the work, however: there was no theory to teach this music, which may be a reason why Schoenberg was reluctant to present the twelve-tone method to students. What could he tell them? That he employed more pitches than in traditional music? Although five tones are “drawn into composition in a way not called upon before,” Schoenberg wrote in an essay titled “New Music,” “that is all, and it does not call for any new laws.”36 As one of the founders of the twelve-tone method, however, Schoenberg was expected to create those laws: to provide a coherent theory to explain this music.37 Despite this avoidance of twelve-tone music that his students longed to hear, out of this course did come an invitation to teach at USC, which we shall explore in the following chapter.

Oscar Levant and David Raksin

Along with these students, how did Schoenberg form a closer connection to the film industry in Hollywood? His association improved markedly through two film composers: Oscar Levant and David Raksin, both of whom had a strong interest in musical modernism. Private students were critical to Schoenberg's financial situation, since film composers were among the few who could more easily afford his prices. With European royalties from Schoenberg's compositions dwindling almost to nothing due to the rise of National Socialism and then the war, the private lessons took on even greater significance as a source of income for a young family.

Levant was one of the first Hollywood composers to take lessons with Schoenberg. As a gifted pianist and one of the country's leading interpreters of Gershwin's music, he came to Hollywood to write and arrange film scores for Twentieth Century-Fox. Levant also had a reputation as the “bad boy of Hollywood,” mainly in terms of his wit, which could be ruthless and so made him a favorite guest at Hollywood parties. Yet he also wanted to be accepted as a serious composer, and Schoenberg's lessons seemed to offer the perfect opportunity of achieving that. Beginning in April 1935 when Arnold was still living in the Hollywood Hills, and then continuing for the next two years, Levant remained in regular contact with his new teacher, and then intermittently after that time.38 Levant also urged his colleagues in the film industry to study with the renowned composer – when would they get such an opportunity again? – and so he became Schoenberg's main connection to the film industry. Schoenberg could scarcely have asked for a more loyal and advantageous contact.

Well before Schoenberg had even arrived in Hollywood, Levant had a growing interest in modern music. With fellow composers at Twentieth Century-Fox, Edward (Eddie) Powell and Herbert Spencer, both of whom later studied with Schoenberg, Levant listened to avant-garde works and read along with the scores.39 They took what Levant called “a communal approach,” which helped in “keeping abreast of developments elsewhere in the musical world.” They met at each other's houses, where they would “play records, break down the instrumentation of certain passages, discuss the technique of the writing and make notes on the effects that were introduced in the scores.”40 Essentially, it took them away from the daily grind of the film studios, and Schoenberg's arrival seems to have spurred their interest in studying modern music further.

Levant was eager to begin. The lessons took place regularly on Tuesday and Friday mornings, which he recalled were “at an hour which required a heroic uprising on my part.”41 Although the details of these lessons elude us, he studied German and Austrian composers with Schoenberg much like in the Alderman classes. Levant longed to learn some aspects of twelve-tone music, yet to little avail. Schoenberg consistently argued that students should approach twelve-tone music only after they had mastered the fundamentals, which of course almost no student in his view was able to do. Undeterred, Levant urged his friends to study with the master, and several complied. Both Spencer and Powell made the dutiful trek to Schoenberg's home in an effort to glean some of his “secrets,” although they, too, seem to have received little or no instruction in twelve-tone music.

Levant's experience with one of his compositions, a string quartet, is illuminating. He asked Schoenberg for his advice on improving the quartet, because Levant had tried assiduously to follow the twelve-tone method. When Schoenberg heard the finished work he allegedly remarked, “It could use a little of your humor.”42 The experience of actually performing the quartet revealed some of the exasperation students often felt in studying with Schoenberg. When Levant first brought up the idea of having it performed, Levant recalled, Schoenberg told him: “At the first playing, you will feel desperate [in despair].”43 Schoenberg was right; reviews of its premiere were not remarkable. Intent on getting his mentor's feedback, Levant pressed Schoenberg to arrange for a private concert. Schoenberg, in turn, invited his old friend Klemperer to hear the string quartet at a private performance at Schoenberg's house. Despite the honor, the evening did not go well. Unforgivably, Schoenberg interrupted the performance numerous times to talk about how earlier composers approached problems in writing string quartets, almost as if it was a lesson in composition. Crestfallen, Levant ruefully recalled that “because of this discussion, my string quartet was completely abandoned.”44 We have only Levant's memory of this event, since Schoenberg never referred to it in his writings, but the experience seems apt. Schoenberg was rarely supportive of his students’ efforts to write modern, twelve-tone music.

Nonetheless, Schoenberg did think enough of Levant's music to include one of his works in a concert funded by the Federal Music Project. At Trinity Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles on April 14, 1937, Schoenberg encouraged Levant to conduct his Nocturne; Schoenberg then led the orchestra in performing works by two of Schoenberg's best students then living in Los Angeles: Gerald Strang and Adolph Weiss. In a nod to his Vienna period, Schoenberg also included Passacaglia, Op. 1 by former student Anton Webern.45 The concert marked perhaps the peak of Levant's association with Schoenberg. Not long afterward, Levant left to work on Broadway shows and perform in New York, and the lessons ended, but the contact did not.

Levant continued to be of use to Schoenberg, who was anxious not to lose contact with his former student. One of the associations to which Levant belonged was the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP). Schoenberg had earlier asked Gershwin to arrange a membership for him, to no avail. With no royalties coming in from Europe, Schoenberg hoped that ASCAP might be able to help him obtain American royalties. He wrote to Levant in January 1939, giving him the titles of six works he had already published in America, and asking him if he could set up a membership with ASCAP. Levant replied in March of that year that he would see to it that a “speedy and effective entrance” to ASCAP happened. He called on the services of Max Dreyfus and Deems Taylor to complete the process, telling Schoenberg that he should hear the official reply by April 1939.46

As months went by, and still no word from ASCAP, Schoenberg became worried. In October 1939 he again wrote Levant, this time in a plaintive tone. It was a striking shift from his days of being dismissive of Levant's work. “Will you answer?,” he asked. “I want to know, whether I am good enough for the ASCAP-people. They need not hesitate to tell me so. I am not offended. But I want to have it black on white.”47 The exiled composer was well-used to disappointments, and seemed to prepare himself for another one. Fortunately, with Levant's insistence, Schoenberg finally became a member, much to his delight. At his first meeting with the association, he sat next to, of all people, a Hollywood songwriter. “You know, Arnold, I don't understand your stuff,” the songwriter allegedly exclaimed, “but you must be O.K. or you wouldn't be here.”48

***

Like Levant, film composer David Raksin tried to improve his composition skills in modern music by studying with Schoenberg. As one of Levant's colleagues at Twentieth Century-Fox and later the composer of the quintessential film noir score for Laura (1944), Raksin was a youthful and talented musician and arranger from Philadelphia when he arrived in Hollywood in 1935 at the age of 23. Unlike Levant, Raksin's background was almost entirely in popular music. His father owned a music store, and was an orchestra director at a major movie theater, the Metropolitan, where young David obtained some of his first professional experience. After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania, Raksin moved to New York to work in Benny Goodman's band, where Levant was the pianist. A band arrangement by Raksin of Gershwin's “I Got Rhythm” persuaded Levant to bring the young musician to Gershwin's attention, who in turn arranged a job for him at Harms/Chappell, a music publishing house in New York, where Raksin wrote and orchestrated songs.49

When the music director at United Artists, Alfred Newman, heard about the budding composer, he invited him out to Hollywood, where Newman assigned him to work with Charlie Chaplin on Chaplin's latest film, Modern Times. It proved to be a curious arrangement; Chaplin, who could not read music, evidently whistled the tunes in his head to Raksin, who hurriedly wrote them down, and then went home to orchestrate them. What might seem simple in fact was a real challenge, because Chaplin was often temperamental and always demanding.50

Chaplin was more than a comedian; he was a symbol, and few Hollywood actors were as much admired by the exiles as was he.51 His image as everyman, the tramp who scoffs at the upper-class, found a ready audience in deeply class-conscious Europe. Many exiles shared this admiration in seeing Chaplin as an innovator, as an artist unafraid to experiment and to explore. Adorno, who with Max Horkheimer starkly critiqued the “culture industry,” waxed almost poetic in describing him:

The one who comes walking is Chaplin, who brushes against the world like a slow meteor even where he seems to be at rest; the imaginary landscape that he brings along is the meteor's aura, which gathers here in the quiet noise of the village into transparent peace, while he strolls on with the cane and hat that so become him. The invisible tail of street urchins is the comet's tail through which the earth cuts almost unawares. But when one recalls the scene in The Gold Rush [1925] where Chaplin, like a ghostly photograph in a lively film, comes walking into the gold mining town and disappears crawling into a cabin, it is as if his figure, suddenly recognized by Kierkegaard, populated the cityscape of 1840 like staffage; from this background the star only now has finally emerged.52

Adorno's admiration for the film star matched Schoenberg's, and through Raksin Schoenberg was finally able to meet him. It seems Levant first told Raksin of Schoenberg's interest in Chaplin, asking if Raksin could arrange a get-together between the two legendary artists.53 Chaplin agreed to the meeting, although he knew very little about art music. The encounter, however, did not go well. Both Gertrud and Arnold Schoenberg came to the meeting, dressed in their most fashionable clothes, yet Chaplin behaved childishly, giggling incessantly and joking. The Schoenbergs were not amused; perhaps it was not what they expected from this famous actor, comedian, and director. They did agree, however, to have their picture taken with Chaplin and Raksin – the only ones in the photograph who are smiling (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Charlie Chaplin, Gertrud and Arnold Schoenberg, and David Raksin, 1935, at Charlie Chaplin Studios.

Raksin finally got up the courage to study with Schoenberg several years later. Always believing he was not yet ready, he had waited until Levant told him in 1938 that the “Old Man” was asking about him; Schoenberg had remembered that Raksin had asked earlier about taking lessons, and now seemed a good time to do so.54 Clearly, Schoenberg needed the money, and Raksin longed to perfect the craft of composition. Before taking him on as a student, Schoenberg asked to see some of Raksin's compositions, and the young man complied. Although Schoenberg saw some merit in these works, he allegedly told him at their first lesson: “First you must learn something about music.”55 So he gave the astonished Raksin many examples from other composers’ works, mainly Haydn and Mozart as well as Webern's Passacaglia, Op. 1. Despite the Webern example, Schoenberg stated at the outset that “I will not teach you composing with twelve notes.”56 The purpose was to see how earlier composers resolved particular musical problems, and so the lessons gave Raksin a connection to the past that he had scarcely known previously. Despite his studies at university, much of what he gleaned had come from work experience in student orchestras, theater orchestras, and now in Hollywood. Schoenberg's tutelage was an entirely different level of education, and Raksin was like a musical sponge.

The relationship seems to have been one of mutual respect. In an interview I held with him almost seventy years later, Raksin still recounted his experiences glowingly with Schoenberg as a teacher. “I think he was a very warm-hearted, wonderful, charming man,” he stated. “I know he appreciated my attitude towards him and I appreciated his towards me.”57 Once per week over a period of several years, Raksin made the trek to Schoenberg's house, sat down at the piano with him, and they studied scores together. One quality Schoenberg always demanded was truthfulness: “he would expect you to be forthcoming about your thoughts and feelings [and] responses,” Raksin recalled. The lessons were thus a kind of give and take, and it was this experience of being taken seriously that Raksin remembered with pride: “We'd sit there and we have a piece of music, and we analyze it and it's a hell of a wonderful way of learning, sitting in front of a piano with a great teacher.”58

George Gershwin

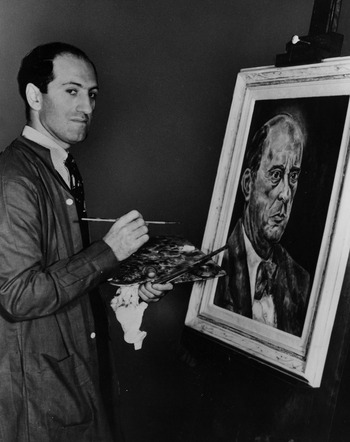

Schoenberg's association with Levant led him to one of his closest, if short-lived, friendships in Hollywood: with George Gershwin. Gershwin considered at one time taking lessons with Schoenberg but never did so; instead, the two merely became friends. They came from radically different backgrounds, yet they found they in fact had much in common, above all their interests in modern music, painting, and tennis. Such a friendship would have been inconceivable in Europe, where Schoenberg would have been mocked by colleagues for associating with figures in popular music. Yet in Southern California almost anything seemed possible, and Schoenberg's increasing interest in writing tonal music may also have been a factor. Levant probably introduced them at Gershwin's rented house on Roxbury Drive in Beverly Hills, where Gershwin, his brother Ira, and Ira's wife Lee had been staying since August 1936. Schoenberg had moved into Brentwood nearby the same summer, and he joined the songwriter's milieu of actors, writers, and musicians on a regular basis. Despite artistic differences, and their ages – Schoenberg was 62, Gershwin was 37 – the mutual respect for each other crossed artistic barriers.

One reason for the bond between the two composers was their common interest in painting. Schoenberg had tried to express his ideas in painting for several years in Vienna during an especially trying time during his first marriage to Mathilde. It was not a happy marriage, and his paintings were filled with anguish, especially when his wife had an affair with an artist with whom Schoenberg was taking lessons.59 Schoenberg briefly took up painting again in Los Angeles but for a very different reason. He and Gershwin both painted self-portraits as well as portraits of each other; one of Gershwin's self-portraits, which he gave to Schoenberg, was evidently one of the last paintings he ever created, and is still in the possession of the Schoenberg family (see Figure 2.3).60 As if to cement this bond, he paid Edward Weston to take several photographs of Schoenberg, and used one of the photographs for a portrait of his new friend (see Figure 2.4).61

Figure 2.3 Gershwin painting a portrait of Schoenberg, December 1936.

One thing was certain: they both loved tennis. At Gershwin's house, friends gathered together by the tennis court, making for much socialization and jovial mixing. As Levant describes it, the court was open “to all their co-workers from New York domiciled in Hollywood.”62 The regular visits for Schoenberg meant that there was an opportunity to be with people he rarely had a chance to meet otherwise. This social circle included songwriters Jerome Kern, Yip Harburg, and Harold Arlen, comedian Harpo Marx, and film composer and conductor Alfred Newman.63 On the Gershwin tennis court on May 26, 1937, Schoenberg first told his incredulous Hollywood friends about the birth that day of his son, Ronald; Schoenberg preferred to be playing tennis with his comrades rather than waiting nervously in the hospital.64 He reveled in the sport, in the attention, and in the friendship. While his tennis skills were limited, he was passionate about playing.

Gershwin's long interest in modern music provided a further bond, and his restless drive to study new methods in composing led him down several musical paths.65 One of his first teachers, Edward Kilenyi, had him study Schoenberg's ideas in composition and harmony, especially the idea of Stufenreichtum, or “step-wise” voice leading by whole- or half-steps. Gershwin later applied this approach in several compositions, such as Rhapsody in Blue (mm. 38–40) and the Concerto in F (mm. 53–72), as well as the bass line in “Do It Again” and the harmonies of “Nice Work If You Can Get It.”66 On a trip to Europe with Ira Gershwin in April 1928, he met with Schoenberg in Berlin, who gave him a signed photograph of himself, dated April 24, 1928.67 The visit formed part of Gershwin's interest in meeting with other European art music composers, including Maurice Ravel and Kurt Weill. Levant described Gershwin's knowledge of art music as “scattered,” yet Gershwin studied Schoenberg's scores along with the music of other modernists, among them Alban Berg's opera Wozzeck and his Lyric Suite, Stravinsky's The Firebird, and Maurice Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe.68 Although there is no record that Gershwin ever took lessons with Schoenberg, their friendship formed part of his strong interest in art music.

Ironically, one of the few known disagreements between Gershwin and Schoenberg arose out of Gershwin's interest in writing a string quartet. According to one version, Gershwin told Schoenberg that the quartet would be “something simple, like Mozart.”69 Perhaps he meant to imply that it would not be twelve-tone or even avant-garde but rather rigorously tonal and melodic in a more traditional sense. Schoenberg understood the remark differently, however – the classic problem of interacting with others in exile. “I'm not a simple man,” Schoenberg allegedly replied, “and anyway, Mozart was considered far from simple in his day.”70 Gershwin rushed to explain himself, but fortunately Schoenberg did not pursue the matter further. Perhaps he realized that he did not want to alienate this friendship as he so often did others.

Within this wider interest of exposing himself to different types of music, Gershwin took the opportunity to hear Schoenberg's music on several occasions. Long before he met his new friend, he had attended the American premiere of Pierrot lunaire, Op. 21 on February 4, 1923 in New York, with his brother Ira in tow.71 That same year Gershwin attended a concert by singer Eva Gauthier, who gave the American premiere of Lied der Waldtaube (Song of the Wood Dove) from Schoenberg's song cycle, Gurrelieder, based on poems by Danish writer Jens Peter Jacobsen on a medieval love tragedy that took place at the Gurre Castle in Denmark; Schoenberg conducted and recorded the work eleven years later in New York with the Cadillac Symphony.72 In 1928 while in Paris, Gershwin attended a concert by the Kolisch Quartet, which played the first movement of Schoenberg's Second String Quartet.73 When Schoenberg arrived in New York in 1933, Gershwin agreed to finance scholarships so that students could study composition with him at the Malkin Conservatory of Music.74 And when a Schoenberg Festival took place at UCLA's Royce Hall in January 1937, George and Ira went to the concerts; we'll consider this festival in further depth in the following chapter. Finally, George and Ira attended a concert that Schoenberg himself conducted: his tone-poem Pelleas und Melisande, which took place during the second half of a Federal Music Project concert on April 14, 1937.75

It is also possible that Gershwin helped his friend by financing the recording of all four of Schoenberg's quartets, which represented the first time that the complete set was recorded.76 Another figure from the film industry, Alfred Newman, was taking lessons with Schoenberg, and he arranged for the event to take place in the United Artists music recording studio, called Stage 7 (later renamed the Sam Goldwyn Studio) at the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Formosa Avenue.77 The recording artists were the Kolisch Quartet (Rudolf Kolisch, violin; Felix Khuner, violin; Eugene Lehner, viola; and Benar Heifetz, violoncello), then on tour from Austria and who had arrived in town to perform the quartets at the Schoenberg Festival. Between December 29, 1936 and January 8, 1937, the ensemble recorded one quartet each day they were in the studio. Since they had often performed the quartets, both under their original name of the New Vienna String Quartet and after 1927 as the Kolisch Quartet, they knew the pieces intimately. Accompanying the recording are remarks by Newman, members of the quartet, and Schoenberg himself, who expressed his delight at the quality of the recordings and the momentous event that the records represented. According to Newman, twenty-five sets were pressed, which cost about $70 each to purchase; among the few who could afford this price were those who worked in Hollywood, including Gershwin, David Raksin, Hugo Friedhofer, and Edward Powell.78 For all of Schoenberg's supposed admirers in Europe, no one was willing to arrange such a venture; Newman was, with Gershwin's help. This event helped reinforce a sense of belonging for Schoenberg in his new homeland, and it was on this occasion that he referred to himself for the first time as a “California composer.”79

Then, almost as suddenly as the friendship between Schoenberg and Gershwin began, it all ended. Although symptoms began appearing as early as November 1936, Gershwin increasingly complained of headaches in early 1937.80 No doctor, however, seemed aware of the seriousness of the headaches, and physical exams yielded nothing concrete. He had dizzy spells, and even briefly blacked out at a concert – one of two public appearances in Los Angeles – when playing his Concerto in F. It took place at the Philharmonic Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles, the city's main concert hall for classical music. Now deeply troubled by his condition, he met with neurologists, who catastrophically declared that he did not have a brain tumor and recommended rest.81 The headaches also worried Gershwin's friends, among them Levant, who assumed the dizzy spells resulted from “his dissatisfaction with working conditions in Hollywood, an expression of his yearning to be elsewhere.”82 When Gershwin collapsed on July 10, 1937, doctors finally operated on a brain tumor, to no avail; he died at the age of 38 of a cerebral hemorrhage on July 11, 1937, and millions mourned in stunned disbelief. Alfred Newman later spoke for many in describing the death as a “frightful and irreparable loss.”83 The voice of one of America's truly innovative songwriters and artists was stilled.

In admiration for a friend and beloved colleague, a memorial concert took place over the Mutual radio network, broadcast for a national audience on July 12, 1937, in which Schoenberg was able to express his heartfelt loss. Both American and émigré musical stars came out to pay their respects: José Iturbi, Otto Klemperer, Johnny Green, Oscar Levant, and others, and they performed some of Gershwin's music. When the announcer asked Schoenberg to say a few words, the composer gave a moving eulogy:

George Gershwin was one of these rare kinds of musicians to whom music is not a matter of more or less ability. Music to him was the air he breathed, the food which nourished him, the drink that refreshed him. Music was what made him feel and music was the feeling he expressed.

Directness of this kind is given only to great men, and there is no doubt that he was a great composer.

What he has achieved was not only to the benefit of a national American music, but also a contribution to the music of the whole world. In this meaning I want to express the deepest grief for the deplorable loss to music. But may I mention that I lose also a friend, whose amiable personality was very dear to me.84

Gershwin's friendship was in keeping with a remarkable aspect about Schoenberg's career in America: more of his friendships appeared to be with people outside the academy than inside. It is not too strong to say that he reveled in this new identity with Hollywood and with figures who shared a mutual fascination with film. When Merle Armitage produced a book in memory of Gershwin the following year, Schoenberg wrote one of the entries, explaining the closeness he felt to this most unlikely of comrades.85 Schoenberg's friendship with a popular American songwriter helped him to identify not only with Hollywood but with the United States, and so Gershwin's death meant more than merely a loss of a friend. It also meant the loss of a vital connection to American popular culture in which a representative of high culture had associated closely with a symbol of popular music.

Compositions

One way that Schoenberg tried to make his music more accessible to California audiences was to return to tonal keys. To the shocked surprise of his contemporaries, the composer chose to write his first American work in a style seemingly more relevant to Hollywood than to the avant-garde to which he had belonged. He had scarcely been in Hollywood more than a month before he began to compose this piece, and three of his friends, Martin Bernstein, Hugo Riesenfeld, and Otto Klemperer, had a role in its composition and premiere.

The result was the Suite for String Orchestra in G Major, which originally arose from his interaction with Martin Bernstein in Chautauqua, New York in the summer of 1934. A professor of music at New York University who was also a double-bass player in the Chautauqua Symphony Orchestra, Bernstein convinced him about the need for writing a work specifically for college students, something Schoenberg had never previously considered. As Schoenberg explained it, Bernstein told him of “the ambitions, achievements and successes of American college orchestras. I became convinced that every composer – especially every modern composer, and I above all – should be interested in encouraging such efforts. For here, a new spiritual and intellectual basis can be created for art; here, young people can be given the opportunity of learning about new fields of expression and the means suitable for these.”86

The idea seems to have been revived at the Hollywood home of Riesenfeld, who invited other émigrés to a Sunday tea. At this jovial gathering on October 14, 1934, the music critic for the Los Angeles Times, Isabel Morse Jones, reported that Schoenberg wrote down a melody for the nascent piece.87 Over the next two months he developed an entire work to help college students learn about modern harmonies and rhythms. Students were often scared away from the dissonant tones of much modern, atonal music, as Bernstein explained to him, so Schoenberg wrote it for a level that was not too modern.

With this piece Schoenberg thus meant to introduce students to the current possibilities of tonality: to provide a bridge for students into the modern repertoire. It was an astonishing goal, given the composer's consistent experimentation over the past two decades with atonality and the twelve-tone method. Although he had integrated tonality with twelve-tone works before, such as the Six Pieces for Male Chorus, Op. 35, the Suite for String Orchestra was clearly different.88 By avoiding what Schoenberg humorously referred to as “Atonality Poison,” students could develop “modern feelings, for modern performance technique,” with an emphasis on “modern intonation, contrapuntal technique and phrase-formation.”89 As he pointed out later in a letter to New York Times music critic, Olin Downes (1886–1955), the piece could “lead them to a better understanding of modern music and the very different tasks which it puts to the player.”90 Assured of its educational value, Schoenberg wrote to his friends in November 1934, while still in the midst of composing it: “This piece will become a veritable teaching example of the progress that can be made within tonality, if one is really a musician and knows one's craft: a real preparation, in matters not only of harmony but of melody, counterpoint and technique. A stout blow I am sure, in the fight against the cowardly and unproductive.”91 Since Schoenberg was teaching students privately while continuing his progress on the work, such an idea made pedagogical sense.

The reception, however, was not what we might expect for a steadfastly tonal work. Otto Klemperer gave the Los Angeles premiere in May 1935 of what the program referred to as the “Suite in Olden Style for String Orchestra.” It was broadcast live on local radio station KHJ, followed five months later by a performance with the New York Philharmonic. The New York Herald Tribune critic, Lawrence Gilman, was particularly savage in his remarks. “Only one thing more fantastical than the thought of Arnold Schönberg in Hollywood is possible,” he scoffed, “and that thing has happened. Since arriving there about a year ago Schönberg has composed in a melodic manner and in recognizable keys. That is what Hollywood has done to Schönberg. We may now expect atonal fugues by Shirley Temple.”92 It was a cutting blow, suggesting that Schoenberg's Hollywood connection had rendered his music simplistic and even backward – the kind of comment Schoenberg rarely heard, even among his enemies. Other critics were similarly baffled by the composer's supposed turnaround and as a result found little to laud in the work.

One of the few who seemed to have something positive to say about Schoenberg's experiment in educational composition was himself a student at the time of the Suite's appearance. Composer Milton Babbitt, who was studying with Martin Bernstein and had eagerly awaited the work's completion, was intrigued. “What for Schoenberg was a multilayered link to the past was for us a multiple, if passive, connection to a tradition that we inherited primarily through its extensions. If the Suite was an edifying compendium for us, it was Schoenberg's bridge between his old and new worlds, and he wasn't about to burn his bridges.”93 That bridge found little acceptance among American audiences – a harsh lesson for someone dependent on commissions for extra income.94

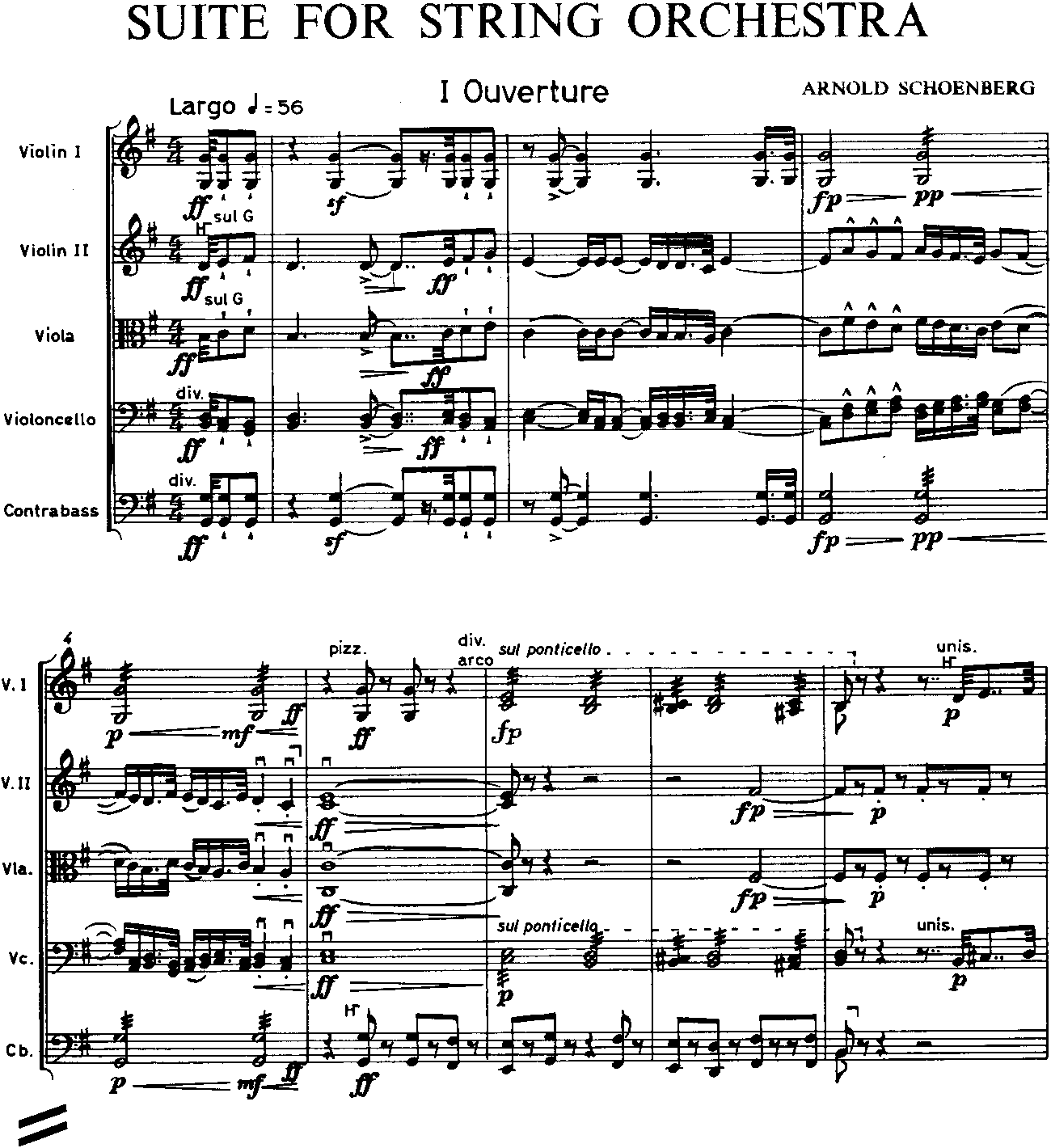

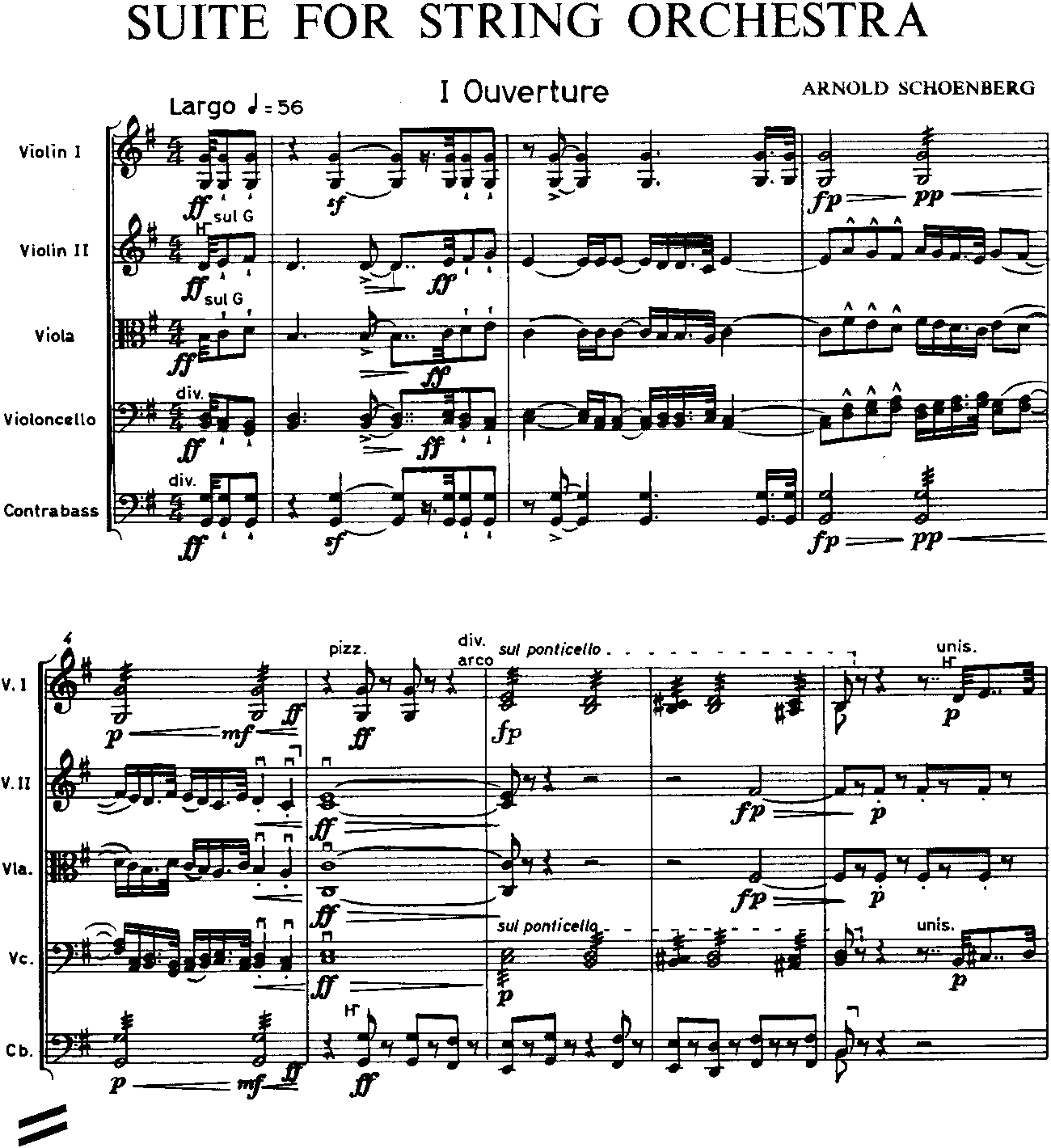

Thus, despite well-meant intentions, the Suite was ultimately more often performed by symphony orchestras than by student orchestras. Here Schoenberg was almost apologetic in his explanation to Downes: “Now, unfortunately,” he explained, “musicians to whom I showed the work when it was finished found it too difficult for pupils, but liked the music very much…And so it came to be that I agreed with the publisher's wishes to let it at first be a normal concert work and only later to develop its original purpose.”95 It was a curious transition, to be sure, especially given Schoenberg's interest in reaching out to new audiences. Scored for violins, violas, cellos, and contrabasses, the work showed a further nod to tradition in the titles for the five movements: Overture, Adagio, Minuet, Gavotte, and Gigue (see Example 2.1).

Example 2.1 Schoenberg, Suite for String Orchestra, mm. 1–9.

To Schoenberg's evolving sense of modernism, it became increasingly important not to leave the possibilities of tonality behind – a process he had already begun in Europe and continued to explore in exile. While that choice was scarcely accepted by his European colleagues, it came after much thought once Schoenberg immigrated to America. He continued to compose twelve-tone works for the rest of his life, including some of his most “experimental” works, such as the String Trio, Op. 45 and Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment, Op. 47. Yet he was also well aware of how Americans often viewed his music. “If people speak of me,” he once complained, “they at once connect me with horror, with atonality, and with composition with twelve tones.”96 Yet to Schoenberg, to be modern meant that one could now write both forms of music and not be restricted to only one type of composition. He addressed this belief in an article first published in the New York Times, titled “One Always Returns” (later reprinted as “On revient toujours”), in which he explained that both types of composition, tonal and twelve-tone, were acceptable because he liked writing in both styles.97 Modernism to Schoenberg in Southern California thus meant at times to embrace the past. If meeting aesthetic challenges meant not burning bridges but rather creating new ones (or at least revisiting old ones), then Schoenberg's work remains an example of reaching out with a peacepipe rather than with a cudgel.

***

The closest Schoenberg seems to have come to writing an actual film score came through negotiations with MGM producer, Irving Thalberg. Salka Viertel arranged the first encounter in October 1935, which she described in her autobiography.98 Like Chaplin, Thalberg was intrigued about Schoenberg, but unlike Chaplin, Thalberg wanted to hire him at a potential salary of $25,000. On the radio he heard one of Schoenberg's most famous pieces, Verklärte Nacht, and was struck by its beauty and grace. He had also evidently read the entry on the famous composer in the Encyclopedia Britannica, one of the very few composers in Hollywood who was listed. Thalberg agreed to the meeting at once, and Viertel personally brought Schoenberg to Thalberg's office.

Thalberg described to them a new movie his studio was filming, based on Pearl Buck's best-selling novel, The Good Earth. There is great commotion, he explained, and the heroine Oo-lan gives birth during an earthquake. This is where the music comes in, exclaimed Thalberg excitedly. “With so much going on,” Schoenberg allegedly interjected, “why do you need music?”99 Thalberg was taken aback; Schoenberg did not seem enthusiastic, and Thalberg was clearly unused to composers who did not show enthusiasm for his projects. The composer then added a startling demand: to have complete control of the music from beginning to end. “I would have to work with the actors,” Schoenberg explained. “They would have to speak in the same pitch and key as I compose it in.”100 Undeterred, Thalberg gamely pressed on, and handed Schoenberg a copy of the script, urging him to read it.

Despite his initial reaction, the composer was interested in the project. At home, he read the script and then created over thirty sketches for different scenes: an “agitated folks scene” in the form of a folk dance; “mood of a landscape” (Landscape Stimme [Stimmung]) using a Chinese pentatonic scale; themes for “Wang's Uncle,” “funeral – death” and love, and so on (see Example 2.2).101 A part of him somehow wanted to live and work in Hollywood and benefit from all that the city promised, while another part held the entire industry in disdain. Nonetheless, similar to his Suite for String Orchestra, he wrote the sketches in tonal keys, as if to mimic the style then prevalent in Hollywood.102

Example 2.2 Schoenberg, sketch for The Good Earth: “Wang's Uncle (Comical).”

Alas, a film contract did not come through. A follow-up call by Gertrud Schoenberg to Viertel took place the following day; she managed all of the family finances, and demanded $50,000 or double what the studio had originally offered. A studio like MGM could easily afford such a sum, yet whether it was the demand for more money or the artistic control that Schoenberg required, or a combination of both, the result was that there was no deal. Incredibly, Schoenberg still clung to the hope that there might be.

Several weeks after their meeting, he still heard no word from Thalberg. Although that in itself was an answer, Schoenberg agonized that perhaps he had made too many demands and asked for too much money. Worried, he wrote the executive a plaintive letter, a rare tone for the composer. “Maybe you are disappointed about the price I asked,” he conceded. “But even in case you are still considering to make me a proposition, I wanted to ask you to give me your decision or at least to write me a letter.”103 He received no reply; Thalberg ended up choosing MGM composer and arranger, Herbert Stothart, to arrange several folk songs for the film, and at any rate, the studio executive died shortly afterwards.

With time, Schoenberg put the encounter in perspective. In January 1936 he wrote to his longtime friend, Alma Mahler Werfel, then still living in Vienna. Herself a legend among artists in both Germany and Austria, she had been married to composer Gustav Mahler and architect Walter Gropius, and had counted artist Oscar Kokoschka among one of her many lovers. Now she was married to Austrian novelist, Franz Werfel. “I almost agreed to write music for a film,” Schoenberg explained, “but fortunately asked $50,000 which, likewise fortunately, was much too much, for it would have been the end of me.”104 It is a curious assertion, especially given his many sketches for the film. Yet it provided an advance warning; when the Werfels came to California as refugees four years later, they, too, confronted firsthand the challenges of dealing with studio executives.

The letter to Mahler Werfel tells us something more. Hollywood studios could have brought release from the hardship of material existence. Schoenberg brought himself to the point, perhaps for the first time in his life, of a willingness to forgo his integrity. “[T]he only thing,” he explained to her with regret, “is that if I had somehow survived it we should have been able to live on it – even if modestly – for a number of years, which would have meant at last being able to finish in my lifetime at least those compositions and theoretical works that I have already begun,” which included Moses und Aron and Die Jakobsleiter. It was an anxiety that haunted him till his dying day: how to finish, to bring to rest, the work that remains unfinished? “And for that,” he concluded,” I should gladly have sacrificed my life and even my reputation.”105

Exile composers: Igor Stravinsky, Ernst Toch, and Hanns Eisler

Schoenberg was hardly the only exile composer, nor the only modernist one, to be drawn to Hollywood. Indeed, musical modernism in Southern California changed dramatically when other prominent European exiles arrived on the West Coast, and to a great extent they sought out work in Hollywood. The film industry was naturally of interest to composers who were by no means from the avant-garde, such as Erich Wolfgang Korngold from Austria and Miklós Rózsa from Hungary, both of whom enjoyed great success and a rare degree of freedom in the industry.106 Yet during the 1930s and 1940s Hollywood studios seemed more open to modernist composers than in the past, or at least willing to try out their talents, whether foreign or native-born. American avant-garde composer George Antheil commented on this change of fortune, noting optimistically in 1936 that music “in the motion picture business is on the upgrade. It may interest musicians to know that I have been remonstrated with because I did not write as discordantly as had been expected.” As he claimed to hear from producers: “We engaged you to do ‘modernistic’ music – so go ahead and do it.”107 Modernist composers, whether avant-garde or no, appear to have provided the film studios with a cultural and intellectual cachet that the studios did not have previously.

Three figures in particular who had contact with Hollywood demonstrate this interest: Russian/French composer Igor Stravinsky and Austrian composers Ernst Toch and Hanns Eisler. To varying degrees, each had an association with Schoenberg and his music. Despite their very different styles of composition, they all had prominent reputations before their arrival in the United States, and they all sought to find their place in the musical landscape of Southern California while in exile. If we can speak of an emerging “LA School” of modernist composers, there is no doubt that it had a strong exile connection.

For much of the twentieth century, the modernist alternative to Schoenberg was Stravinsky. Although this rivalry was perhaps spurred on more by their respective followers than by the composers themselves, they did little to abate the differences between them. Schoenberg once referred to Stravinsky as “der kleine Modernsky” (the little modern one), whereas Stravinsky sniffed at Schoenberg's twelve-tone music as so much musical authoritarianism (although that perception was to change after Schoenberg's death, when Stravinsky adopted serialism). After attending an interdisciplinary arts festival in Weimar in 1923, Stravinsky wrote a friend that “I saw with my own eyes the gigantic abyss which separates me from this country [Germany] and the inhabitants of Central Europe as a whole.” Above all, he detested “the IMPRESSIONISMUS of Schoenberg,” and later went even further in proclaiming that “[a]part from jazz, I detest all modern music.”108 Although the statement may seem curious from one closely associated with musical modernism, there is no doubt that he felt increasingly estranged from the developments that Schoenberg and his school personified.

Stravinsky became an exile by choice. Since he was Russian-Orthodox rather than Jewish, and did not criticize fascist regimes (quite the contrary, he initially supported them, as Richard Taruskin and others have addressed), there is little chance that he would have been imprisoned or executed, yet he left Europe for the United States once war broke out.109 His arrival in Southern California in 1939 directly affected Schoenberg, because the battle lines between the two composers suddenly took on renewed force. A heated debate that first appeared in Europe in the early 1920s between the schools of twelve-tone and neoclassical music had thus transferred fully to the land of sunshine by the early 1940s.

Stravinsky had a major advantage over Schoenberg: his music was far better known and performed in America. Prior to his exile, Stravinsky had already made two American tours in 1925 and 1935 before permanently immigrating in 1939. Remaining in Los Angeles until 1969 – longer than any other city he lived in, including Paris – he developed a close circle of friends among the exiles, at first primarily Russian, then English and even German, thereby ironically joining Schoenberg's social network. Among his closest English friends were writers Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood, themselves benefiting greatly from Hollywood, and among the “Schoenberg circle” he enjoyed the company of Thomas Mann, Franz Werfel, and Otto Klemperer, all of whom had direct knowledge of the tensions between the two composers.110

Nor could it have helped matters that Stravinsky differed from most other exile composers in America in that he lived mainly from commissions and performances of his music, whereas many exiles had to find other ways of supporting themselves, such as through teaching. Indeed, Stravinsky abhorred teaching – one of his sole students was an elderly American composer, Earnest Andersson – and because his music was in great demand, he could charge $1,000 or more per performance, more than Schoenberg typically charged.111 In appreciation for his contributions to the country's musical culture, Stravinsky was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1949 (later called the American Academy of Arts and Letters), which was a recognition that Schoenberg never received. Further, whereas Schoenberg never signed a film contract, Stravinsky made an agreement with Walt Disney for the use of his piece Rite of Spring in the film Fantasia (1940), for which he reputedly received $6,000 as the sole living composer of the film's original soundtrack.112 Visiting the Walt Disney Studios in December 1939 with his friend, Russian émigré choreographer George Balanchine, Stravinsky heard the edited cut of his music and evidently approved of its use; the contract, at any rate, gave Disney full control over the score and worldwide distribution rights. A photographer from the Herald-Examiner recorded their visit to one of the other scenes of the film, “Dance of the Hours,” from Act III of the opera La Gioconda by Amilcare Ponchielli (see Figure 2.5). Although certainly no film composer, Stravinsky benefited from, and continued to seek out, contracts with Hollywood studios.113

***

By contrast, two Austrian exiles, Ernst Toch and Hanns Eisler, were products of Viennese modernism and culture. Both had ties to Schoenberg, both had Jewish roots, and both worked in Hollywood. What united them further was the desire to cross the barriers that seemed to separate popular music from art music. In part this approach was a product of exile and the need for income, and in Hollywood they struggled to circumvent the restrictions that the film industry placed upon them.

Unlike Stravinsky, Toch was not an exile by choice. Born in Vienna, he had been a rising star in Europe, and had experimented with the free use of dissonance since the 1920s. By all accounts a kind and modest man, his career took a very different direction after being forced into exile as a Jew, despite being fully assimilated and feeling little attachment to Judaism. Schoenberg played a role in his immigration; prior to fleeing Europe in 1934, Toch asked for and received a letter of reference from Schoenberg for Toch's first American position as a lecturer in music at the New School for Social Research in New York.114 He was invited to teach music courses and, as one of the most welcoming institutions in America for exiles, it became his professional home for his first two years in America.115

Toch left New York for Hollywood, however, with considerable help from George Gershwin. He arranged for Toch to gain membership to ASCAP, which was critical for obtaining royalties for his American works, since like Schoenberg his European royalties had evaporated. According to Toch's wife Lilly, Gershwin was “very fully informed about my husband's activities and even works,” and arranged for him to write his first film score with Paramount in 1935, Peter Ibbetson, starring Gary Cooper and based on a novel by French-born writer George Du Maurier.116 Although Toch earned the comparatively grand sum of $750 per week, the work proved frustrating; Paramount did not want Toch to orchestrate the score, even though he had superb orchestration skills. Nonetheless, the score was later nominated for an Academy Award and was even favorably reviewed by Olin Downes – a great compliment for any composer and certainly for one working in Hollywood.117 Toch subsequently toiled for three years in the film studios, writing background music that went largely uncredited. Although never satisfied with studio conditions, he attracted the attention of several young film composers who sought him out as a teacher, including Alex North, André Previn, and Hugo Friedhofer.118

Thus we have the conundrum of trying to place an art music composer in the category of film composer. Contrary to the belief that composers of art music had little place in Hollywood, Toch at first found modest success. A case in point concerns his work in Bob Hope movies; Paramount executives assigned Toch to write the score to a “comedy horror” film, The Cat and the Canary (1939), and were pleased enough with the result to hire him for a subsequent Bob Hope picture, The Ghost Breakers (1940). Toch increasingly endeavored to write not simply background music but to bring his modernist skills to the screen. In other words, he saw film scoring as an art form in itself. According to music critic Isabel Morse Jones, Toch's score for The Ghost Breakers seemed “ultra modern,” and his ability in “creating fear and suspense in an audience [was] amazing.”119 Two further scores, for Ladies in Retirement (1941) and Address Unknown (1944), like Peter Ibbetson were nominated for Academy Awards, so he received some recognition by the film industry for his work.

Why would a modernist composer of art music seek steady employment in Hollywood studios? The answer is simple: he wanted to work, and as an exile, he had few choices. Toch ultimately became disillusioned, however, although not for failing in the industry, but on the contrary, for succeeding. In writing to a friend he posed a dialectic. “Everything has become grotesquely improbable,” he wrote. “With every success that my film scores have, everything gets more difficult for me.”120 Unlike Schoenberg or Stravinsky, who never wrote an actual film score, Toch enjoyed considerable renown by producers and directors in that he could largely meet their demands. Yet he feared that he was unable to “play the game,” and searched longingly for other avenues for professional fulfillment.

To some degree he found it, like Schoenberg, in academia. Among those who worked in the film industry, Toch was surely one of the only exiled composers to have a doctorate, which he had received in 1921, and so a teaching position was readily within his reach. In 1940 USC gave him the Alchin Chair in composition (a temporary position with a renewable contract) for $1,500 per year – the same chair that Schoenberg previously held, which we shall consider in the next chapter. Although no princely sum, it was regular work that he evidently enjoyed, and he included both Schoenberg's and Stravinsky's music in his lectures. Aside from teaching theory and composition, he also lectured on “Music Direction for Cinema” for the Department of Cinema as one of the few lecturers to have personal insight into Hollywood.121

As an exile in academia, Toch shared some aspects in common with Schoenberg while forging his own path. A text on music theory, The Shaping Forces in Music, met with enough approval to go into at least two further editions.122 Although Toch invited Schoenberg to write the preface to the text (Schoenberg politely declined), he offered a distinct alternative to the twelve-tone method, which he came to disdain in favor of a neoclassical style that seemed more akin to Stravinsky's ideas. Like Schoenberg, Toch also explored aspects of Judaism in such works as the Cantata of the Bitter Herbs, Op. 65 (1938), on the exodus of the Jews from Egypt, and Folk Songs of the New Palestine (1938), a subject we'll take up in Chapter 5. This body of work ultimately resulted, like Stravinsky but unlike Schoenberg, in Toch being elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1957.123 As a composer who experimented with a variety of forms of composition, transitioning from film to academic work, Toch became an important contributor to the “LA School” of exile composers.

***

Similarly, Hanns Eisler saw film as only one outlet, if a vital outlet, for his talents. One of the last modernist composers in exile to come to Hollywood, he was a controversial figure in both Europe and America, largely due to his strong sympathies with socialist causes. He studied intensively with Schoenberg during the early 1920s in Vienna, and although they became estranged over their political differences, they re-established their friendship through correspondence even before Eisler moved to Southern California in 1942. Schoenberg thought highly of Eisler's talents, and in a letter to the director of the St. Louis Institute of Music in 1940 regarding a position for which Eisler applied, he placed Eisler first in a list of his “best pupils of 1919–1923.”124 Equally at home in both the twelve-tone method and in the tonal music demanded by the film industry, Eisler was by all accounts witty, popular among his colleagues, and supremely talented, making unique contributions to the modernist movement in Southern California before running afoul of the US government concerning his leftist past, a subject we will take up in Chapter 6.

Although alienated from Schoenberg's political stance, Eisler had learned much from his mentor. The son of a prominent Jewish philosopher and a Catholic mother, Eisler served in World War I before studying with Schoenberg in the Viennese suburb of Mödling from 1919 to 1923, precisely the time when Berg and Webern were exploring radically new approaches to composition.125 The three young composers were among the first Schoenberg protégés to experiment with the twelve-tone method. Eisler shared with Schoenberg the common experience of being veterans of World War I – although in contrast to Schoenberg, Eisler was wounded several times – and the absolute certainty never to allow such madness to happen again. The necessity of exploring new means of composition was in part a product of the war, and Eisler absorbed all that he could from his mentor in seeking to perfect his craft.

His work with Schoenberg proved beneficial. Although already proficient in counterpoint and harmony from his studies at the New Viennese Conservatory, he knew little about music history. Schoenberg immediately set out to fill the gap with his usual analysis of the works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms, “the cornerstones of his teaching,” as Eisler related.126 Group classes, meeting twice per week, were the norm. Eisler was deeply grateful for the lessons by Schoenberg, who taught the poor student for free. “I can say that it was really there that I first learnt musical understanding and thinking,” he recalled. “Honesty, objectivity, clarity and imaginativeness were also in evidence in the way Schoenberg performed music…What he taught ranged from the simplest technical information and a contempt for the commonplace, the trivial and empty musical formulae to the performance of masterpieces.”127 Schoenberg also oversaw Eisler's growth as a composer. A prominent future seemed assured with Eisler receiving Vienna's Künstlerpreis (Artist's Prize) in 1925 for his Sonata, Op. 1, a strongly atonal work reminiscent of Schoenberg's middle period.128

The relationship with Schoenberg, however, was complex. Eisler was one of the few students willing to challenge and even contradict his mentor. In a letter to Alexander Zemlinsky, from whom Schoenberg took lessons for several months as a young man, Schoenberg commented on this fact, stating “that [Eisler] was the only one of my pupils with a mind of his own, and who didn't blindly adhere to everything.”129 However, problems that arose between them broke out most heatedly over Eisler's increasing rejection of Schoenberg's political conservatism and even twelve-tone music itself. As Eisler later recalled, he sought “to avoid discussing politics with Schoenberg, because nothing came from it.”130 When Eisler left Vienna for Berlin in 1925, ironically the same year that he won the Künstlerpreis, he claimed the need to escape the rigidity and sterility of Viennese musical culture, and already was separating himself from Schoenberg's world.131