The Rise of Gay Rights and the Fall of the British Empire

The Rise of Gay Rights and the Fall of the British Empire 1 - Democracy and Patriarchy

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2014

Summary

John Locke, the father of liberal constitutionalism, begins the great argument of the Second Treatise only after he has refuted Filmer's patriarchal defense of absolute monarchy in the First Treatise. It is a tribute to the power and influence of Locke's argument for liberal democracy in the Second Treatise that almost no one, except a few feminists, even read let alone remember the First Treatise. But the few feminists, such as Carole Pateman, who have taken the First Treatise seriously are, I have come to think, on to something. It may be that Locke never grappled with the degree to which even he did not take seriously the ongoing tension between democracy and patriarchy, even in his own argument. In Nathaniel Hawthorne's great novel, The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne certainly thought so, and in a recent book in part inspired by Hawthorne, The Deepening Darkness, Carol Gilligan and I have tried to clarify how and why the tension between democracy and patriarchy remains so unexamined in American politics, to sometimes catastrophic effect. My aim here, consistent with this larger argument, is to offer a historically informed account of the tension between democracy and patriarchy, including both its underlying personal and political psychology and how it may be and has been resisted.

Moral philosophers differ in their sense of the basis for ethics, some pointing to reason, others to emotion. There is reason to doubt that any basis for ethics can be valid that so rigidly enforces the gender binary (reason as male versus emotion as female) and is so false to the interdependent role of reason and emotion in our ethical lives. I offer human relationality as an alternative, more reasonable basis for the role ethics plays in human life. By human relationality, I mean our empathic capacity to read the human world, to enter into and interpret and give weight to the emotions and thoughts of humans, our own point of view as well as others. I believe its naturalistic basis can be seen in three remarkably convergent findings of the contemporary human sciences: neurobiology, the research on babies, and the evolutionary origins of mutual understanding.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

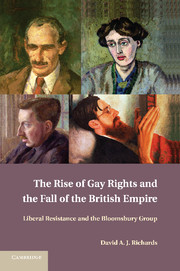

- The Rise of Gay Rights and the Fall of the British EmpireLiberal Resistance and the Bloomsbury Group, pp. 11 - 39Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2013