Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Rewind, Replay

- 1 We’ve Got It Taped

- 2 Shrugging Off the Recession

- 3 Threats and Benefits

- 4 Regulation and Adaptation

- 5 Independent Spirit vs Corporate Muscle

- Conclusion: Video Legacies

- Select Bibliography

- Select Film/TV/Videography

- Select Periodicals

- Index

3 - Threats and Benefits

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 November 2022

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Rewind, Replay

- 1 We’ve Got It Taped

- 2 Shrugging Off the Recession

- 3 Threats and Benefits

- 4 Regulation and Adaptation

- 5 Independent Spirit vs Corporate Muscle

- Conclusion: Video Legacies

- Select Bibliography

- Select Film/TV/Videography

- Select Periodicals

- Index

Summary

The Video Explosion has created a confusing number of companies who are jostling for your business. Some offer excellent services or products, while others seem to spring up overnight only to disappear just as quickly.

Walton Video, ‘Aiming to be Britain's most Professional Team’,

Video Business supplement (June 1982)

By the beginning of 1982, the future of the video market was in the balance. Major distributors were making strong advances in software penetration: the top five rented titles of 1981, for example, were all major studio productions. Independent distributors, consequently, were feeling the pressure. However, for all that bigger organisations such as CIC – whose video release of Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) was the most rented title of 1981 – and the likes of Thorn/EMI and Warner – companies that, along with CIC, dominated that year's sales charts – media reportage around home video tended to focus squarely on the output of independents, specifically videos released within the horror, exploitation and sexploitation modes: what journalists and moral campaigners described as ‘video nasties’. Indeed, media reportage of grisly marketing campaigns conducted by comparatively small outfits such as Astra, VIPCO and Go to promote exploitation titles such as Snuff (Michael Findlay, 1976), The Driller Killer (Abel Ferrera, 1979) and SS Experiment Camp (Sergio Garrone, 1976), which included the foregrounding of violent imagery, suggestive taglines and claims as to the ‘strong uncut’ nature of the films, compounded the idea that video distributors were hellbent on operating beyond the realms of public decency.

The video nasties panic, leading to the eventual banning of thirty-nine videocassettes under the Obscene Publications Act 1959 (OPA), would spark significant changes within the video industry; namely the passing of the Video Recordings Act 1984 (VRA), which stipulated all videos must be certified by the BBFC prior to being released to the general public. Yet the video nasties panic was by no means the only problem, nor for that matter the most imminent, for the video business in 1982. When the panic was first initiated by the media in May, the most immediate threat to both distributors and dealers was the impending rationalisation of what, by this point, was a very crowded marketplace.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

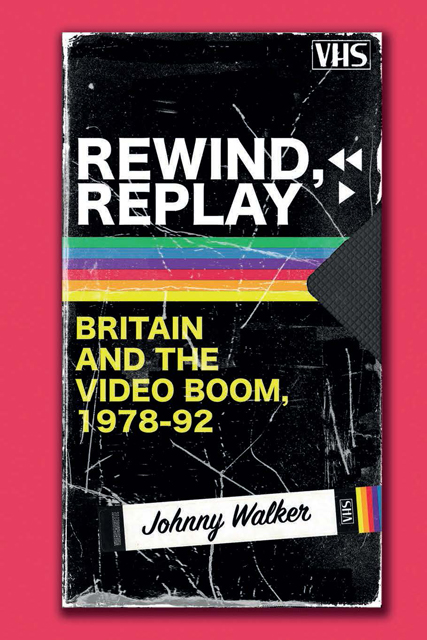

- Rewind, ReplayBritain and the Video Boom, 1978-1992, pp. 95 - 132Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2022