Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Asian primates

- Part III African primates

- Part IV Neotropical primates

- Part V Broader issues

- 15 Economic aspects of primate tourism associated with primate conservation

- 16 Considering risks of pathogen transmission associated with primate-based tourism

- 17 Guidelines for best practice in great ape tourism

- Part VI Conclusion

- Index

- References

17 - Guidelines for best practice in great ape tourism

from Part V - Broader issues

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Asian primates

- Part III African primates

- Part IV Neotropical primates

- Part V Broader issues

- 15 Economic aspects of primate tourism associated with primate conservation

- 16 Considering risks of pathogen transmission associated with primate-based tourism

- 17 Guidelines for best practice in great ape tourism

- Part VI Conclusion

- Index

- References

Summary

Introduction

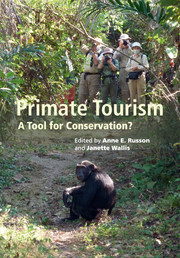

Tourism based on the viewing of great apes is increasingly promoted as a means of generating revenue for range states, local communities, and the private sector (e.g. GRASP, 2006). This is despite known risks from tourism, including disease transmission, which have caused concern among conservationists and prompted the International Union for Conservation of Nature to publish guidelines on best practices for great ape tourism (Macfie & Williamson, 2010). IUCN is one of the world’s most respected authorities on species conservation, and brings together governments, UN agencies, and NGOs to conserve biodiversity and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable.

Great apes are of high conservation concern because all species and subspecies are listed as Endangered or Critically Endangered (IUCN, 2013) and are protected throughout their range by both national and international laws. They are particularly appealing to human observers because they are behaviorally and physically so similar to people. However, their genetic closeness also makes great apes susceptible to human diseases for which they have no immunity (in this volume, see chapters by Dellatore et al.; Desmond & Desmond; Goldsmith; Muehlenbein & Wallis; Russon et al.).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Primate TourismA Tool for Conservation?, pp. 292 - 310Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2014

References

- 10

- Cited by