Book contents

- Politeness in Ancient Greek and Latin

- Politeness in Ancient Greek and Latin

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I Introduction

- Part II The Expression of Im/Politeness

- Part III Im/Politeness in Use

- Part IV Ancient Perceptions on Im/Politeness

- Glossary

- References

- Index Rerum

- Index Locorum

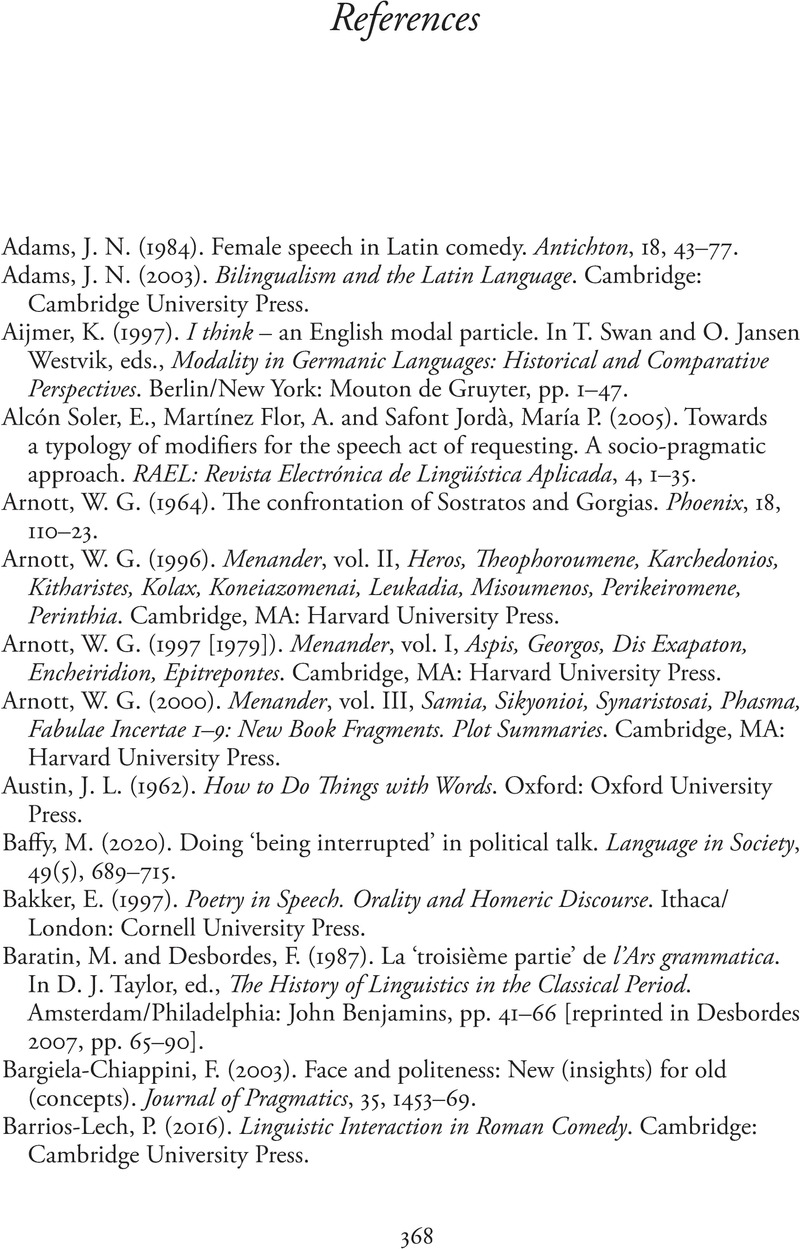

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 September 2022

- Politeness in Ancient Greek and Latin

- Politeness in Ancient Greek and Latin

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Contributors

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Part I Introduction

- Part II The Expression of Im/Politeness

- Part III Im/Politeness in Use

- Part IV Ancient Perceptions on Im/Politeness

- Glossary

- References

- Index Rerum

- Index Locorum

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Politeness in Ancient Greek and Latin , pp. 368 - 403Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022