Book contents

- Philosophy and the Language of the People

- Philosophy and the Language of the People

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Early Humanist Critics of Scholastic Language: Francesco Petrarch and Leonardo Bruni

- Chapter 2 From a Linguistic Point of View: Lorenzo Valla’s Critique of Aristotelian-Scholastic Philosophy

- Chapter 3 Giovanni Pontano on Language, Meaning, and Grammar

- Chapter 4 Juan Luis Vives on Language, Knowledge, and the Topics

- Chapter 5 Anti-Essentialism and the Rhetoricization of Knowledge: Mario Nizolio’s Humanist Attack on Universals

- Chapter 6 Skepticism and the Critique of Language in Francisco Sanches

- Chapter 7 Thomas Hobbes and the Rhetoric of Common Language

- Chapter 8 Between Private Signification and Common Use: Locke on Ideas, Words, and the Social Dimension of Language

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

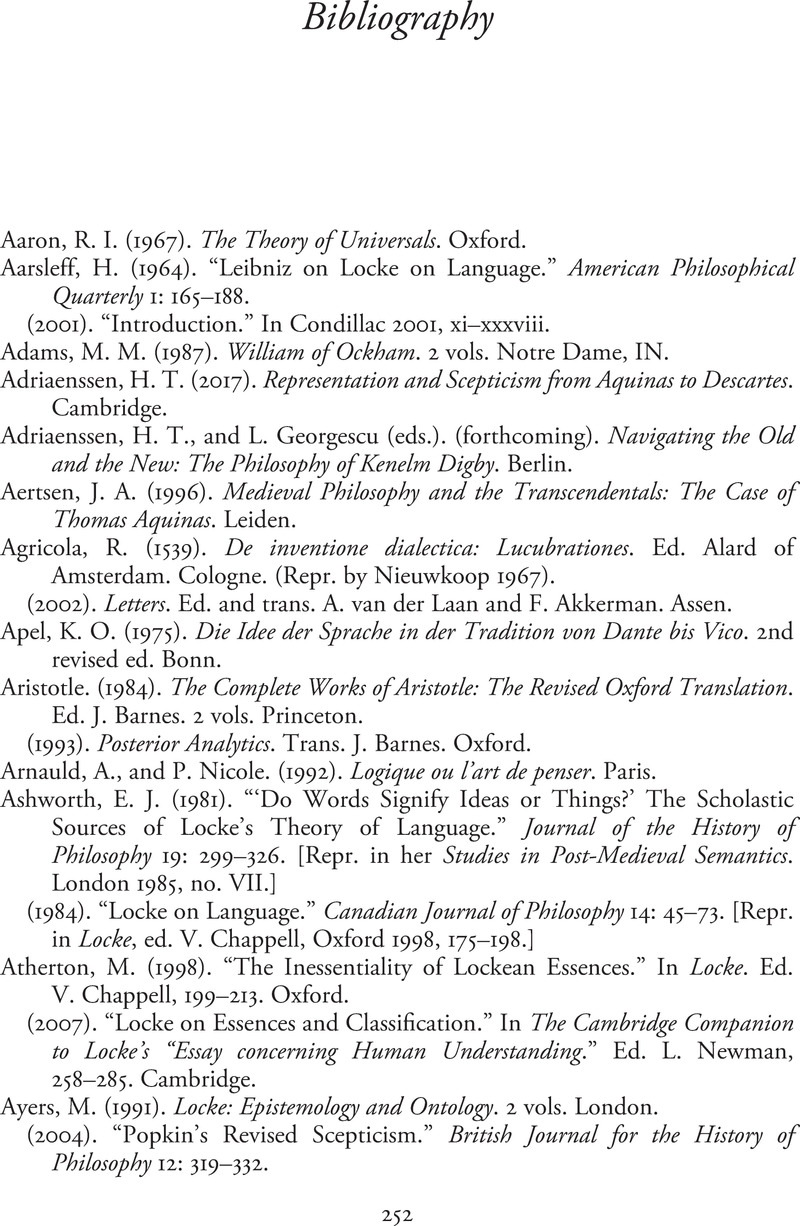

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 July 2021

- Philosophy and the Language of the People

- Philosophy and the Language of the People

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Early Humanist Critics of Scholastic Language: Francesco Petrarch and Leonardo Bruni

- Chapter 2 From a Linguistic Point of View: Lorenzo Valla’s Critique of Aristotelian-Scholastic Philosophy

- Chapter 3 Giovanni Pontano on Language, Meaning, and Grammar

- Chapter 4 Juan Luis Vives on Language, Knowledge, and the Topics

- Chapter 5 Anti-Essentialism and the Rhetoricization of Knowledge: Mario Nizolio’s Humanist Attack on Universals

- Chapter 6 Skepticism and the Critique of Language in Francisco Sanches

- Chapter 7 Thomas Hobbes and the Rhetoric of Common Language

- Chapter 8 Between Private Signification and Common Use: Locke on Ideas, Words, and the Social Dimension of Language

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Philosophy and the Language of the PeopleThe Claims of Common Speech from Petrarch to Locke, pp. 252 - 270Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021