Chapter 1 From sentimental sympathy to activist self-judgment

Defining sympathy

When immediate abolitionists started fighting against slavery in the 1820s, sympathy was regarded as a “natural” human practice, but scholars debated its nature. Physiologists and pathologists regarded sympathy as an involuntary correspondence among body parts or people, a communications system hardwired into human bodies. For them and for the abolitionists who read their work, sympathy meant “a relation between two bodily organs or parts (or between two persons) such that disorder, or any condition, of the one induces a corresponding condition in the other.”1 Neurologist Thomas Willis (1621–1675) had explained this phenomenon within individual bodies as early as 1664, in Cerebri anatome: according to him, a “sympathetic trunk” provided the core of each human body, with its roots in the brain and its tendrils sent into every nook and cranny of the body through a massive nerve-distribution system. This sympathetic trunk provided a means of communication or “sympathy of the parts,” without necessarily involving the brain or consciousness at all. As late as 1836, physicians still spoke of “the powerful sympathy that exists between [the stomach] and other organs” and referred to the “sympathy” between the digestive organs and the skin.

By the early nineteenth century, however, this physiological notion of sympathetic correspondences had drifted from the internal bodily sphere into the interpersonal sphere. Individuals were understood to be “similarly or correspondingly affected by the same influence,” or prone to “affect or influence one another.” Many abolitionists, then, viewed the performance of “fellow feeling,” wherein one person was “affected by the condition of another with a feeling similar or corresponding to that of the other,” as an involuntary aspect of being human. Most argued that sympathy produces only “corresponding” emotions, rather than a “conformity of feelings, inclinations, or temperament.”

Distinguishing among these competing nineteenth-century ideas about sympathy, especially as they circulated within specific performance settings, is crucial. So is refusing to elide nineteenth-century sympathy with empathy or the present-day idea of sympathy as “being thus affected by the suffering or sorrow of another”: for nineteenth-century practitioners of sympathy, pain was not necessarily a prerequisite.

Although early nineteenth-century female abolitionists regarded each other as engaged in disparate types of performances of sympathy, contemporary scholarship on them routinely collapses or erases these contradictory experiences and viewpoints. This is particularly true of black women’s performances of sympathy with the slave, because oftentimes early abolitionists are implicitly or explicitly figured as white. This chapter illuminates sympathetic abolitionist performances by differentiating among varied performances of sympathy, by distinguishing sympathy from empathy, and by historicizing specific, dialogic performances between black and white Garrisonian women as well as debates among black activists.

Lauren Wispe and Marjorie Garber have usefully offered brief histories of empathy, but without an interest in examining its roots in sympathy or discovering the ways in which sympathy haunts or might productively critique empathy and inter-subjectivity.2 Susan Leigh Foster has published an illuminating critique of sympathy and empathy as they anchor colonial expansion and alter notions of kinesthesia in the world of dance. But performance practices can be put to various, contradictory, and competing ends, and a number of women within Garrison’s wing of the anti-slavery movement deployed sympathy against the colonialist impulses it was meant to anchor.

As they gathered in homes, churches, and town halls to form literary and anti-slavery societies, these women rehearsed activist “conversations,” engaged in abolitionist “dialogues,” recited poems, gave speeches, and shared narratives. As they performed, they altered public sentiment, drew followers to the cause, collected signatures for anti-slavery petitions, disseminated testimonies to legislators, and attacked religious and political institutions. They calibrated their performance strategies as they practiced their conversations and dialogues and as they learned from predecessors like Frances Wright, whose anti-slavery scheme, grounded in the mathematical calculations of capitalism, failed quite publically in the late 1820s. Black and white Garrisonian women learned from each other, too, debating how to take advantage of and transform the mainstream practice of sympathy into the more efficacious performance of “metempsychosis” – a practice rooted in collective dedication to self-judgment and practical action rather than individual evangelical Christian suffering and redemption. Drawing on the liberal traditions of Quakerism and Unitarianism as well as the East Indian notions of transmigration or “metempsychosis” which surfaced in critiques of British imperialism, Elizabeth Chandler and Sarah Forten publically debated and refined one another’s approaches to performing anti-slavery through an exchange of poetry that was recited in abolitionist homes across the Northeast and Midwest in the early 1830s.

These women revised the sympathetic practice outlined in Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments. Smith followed fellow scholars Frances Hutcheson (1694–1746) and David Hume (1711–1776) in focusing on sympathy, reason, imagination, and spectatorship as the keys to ethical action. These men all considered themselves empiricists: they rejected the idea that morality could be defined from a transcendent position. In fact, their contemporaries attacked them for their relativity, because they refused to establish universal rules for ethical behavior and focused instead on the embodied processes of everyday life, the relationships among participants within a set of given circumstances.3

Modeling their understanding of sympathy on the involuntary “sympathetic trunk” that united body parts within the human body, Smith and his contemporaries viewed sympathy as the primary link among humans. Initially, they argued that sympathy was God-given: Francis Hutcheson, under whose guidance Adam Smith studied at the University of Glasgow, transferred the neurological idea of a sympathetic trunk into the sphere of the soul, contending that humans had a “sympathetick sense” in their souls that caused a “contagious” sympathy and naturally proved God’s goodness.4 This idea of the “contagion” of sympathy, if not its God-given status, lasted into the mid-nineteenth century – and traces of this idea still surface.

Intriguingly, the periperformative “contagion,” this outcropping from sympathy, suggests the anxiety that the elite associated with sympathetic practice: sympathy could quickly spread throughout a community, endangering the status quo instead of achieving its initial intent to place groups of people in hierarchical relation to one another. Alexander Gerard (1728–1795) argued that sensibility moved a reader to feel “as by infection” the passions of a literary work: embodied performance was particularly combustible. Hume agreed that moral actions were “more properly felt than judg’d of,” and thought “a mutual dependence on, and connexion with each other” led individuals to respond sympathetically to one other. This sympathetic response, in turn, precipitated “a reciprocal relation of cause and effect in all [our] actions.” Strikingly, this term “reciprocal” surfaces early and often within abolitionist coverage of interracial efforts: for instance, when the black and white women of the free produce societies in Philadelphia began to visit back and forth in 1830 and 1831, “reciprocal good feeling” emerged.5 This was not the “infectious” emotion of hysterical or contagious women, but the shared sense of usefulness among activists dedicated to a common goal. This was a radical “contagion” that threatened the state.

Enlightenment scholars posited that three interlocking qualities – sympathy, a love of oneself, and reason – enabled humans to “act suitably” in relationships with others. Present-day scholars often focus on only the first of these three practices within abolitionism, but to immediate abolitionists who performed resistance to state violence, they were interlocked and of equal importance. For them, sympathy was a public action with the potential to cause a “conjunction of Interest” and right an imbalance in a given community.6 Furthermore, sympathy, in their view, led individuals to act reasonably, to redress grievances. Like Hutcheson, they viewed humans as happy only if they responded in sympathy to one another, and only if they felt independently of their own self-interest, desiring both the general good and their own happiness.7 Another philosopher, Edmund Burke (1729/30–1797), viewed sympathy as a God-given, involuntary passion that united humans, but Garrisonians differed from Burke on many crucial issues: they did not embrace his notion that humans take pleasure in others’ pain or his idea that contemplating the painful effects of “blackness” led to the sublime. Contemporary scholar Marcus Wood has usefully critiqued the silent white consumers of sentimental British literature, excited to “sublime” terror through their imaginings of slaves’ pain: their voyeuristic excitement substitutes for a genuine political engagement. Garrisonian women ridiculed such consumers of sentiment and tied their sympathetic practice to economic and political acts.

They were more interested in Burke’s telling corollary: the idea that people want to bear witness only to suffering that they want to redress. Increasing the desire for redress was the key goal for these women. It was not enough to enter anti-slavery circles with a desire for “transient excitement, or for a display of benevolent feeling, or the indulgence of an amiable humanity,” but required an “exertion” to remedy the situation, despite the impossibility of “avoiding a participation in guilt.” Elizabeth Chandler’s 1829 essay “Indifference” reveals how American activists faced a different challenge than their British counterparts, whose reading public devoured romantic representations of the slave in Wood’s account: audiences in the United States did not want to think about slaves at all. Chandler recounts, with astonishment, that after she tells neighbors and friends “harrowing” stories of the wrongs against free blacks and the sufferings of slaves, they “turn coldly away and answer, ‘All this may be very true – but why do you tell it to us? The fault is not ours, nor the remedy in our power.’” And yet, Chandler continues, these auditors view slavery as “criminal” and wish for its abolition. The problem was that their desire for redress was insufficient to overcome their sense of indifference or helplessness.8

Metempsychosis, which involved self-judgment, was designed to intensify and activate that desire for redress through daily abolitionist engagement: initially through “conversation, not only in your stated meetings for its discussion, but while you are engaged in your daily occupations, or when you have gathered into a friendly circle around the evening hearth.” When Chandler’s listeners asked what more they could do than offer best wishes to abolitionists, she pressed them: “You can do a great deal more – you can give it your active exertions – and you must do so . . . form yourselves into societies . . . prevail upon your friends to do likewise . . . let the general attention be but thoroughly excited, let men be forced into the necessity of acting, and efficient remedial measures will soon be devised and adopted.” It was woman’s duty to respond sympathetically to the slave because that was the means of activating public sentiment for redress. Sympathy without action was unacceptable.9

To be fully human, Enlightenment theorists contended, was to be able to suffer. Suffering and sympathizing with one another, however imperfectly and with restraint, created community. Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), in An Introduction to the Principles of Reference Bentham1789, cast sympathy as a “bias to feel for individuals, subordinated groups, nations, humankind, creatures in general.” This “natural” sensibility for the downtrodden was tied to a desire to redress injustices. As Wood, Foster, and others have demonstrated, Bentham justified racial, gender, and class exclusions: in fact, he listed thirty-two different levels of sensibility or intensities of feeling, concluding that elite northern European men “naturally” possessed more of this precious commodity. He believed that a person’s “race or lineage” affected his ability to feel as well as his “moral, religious, sympathetic, and antipathetic biases”: this necessitated a strong government to order citizens’ sensibilities.10 His cartography of sensibility posits that the slave and Native American cannot feel as their “natural” superiors can, thereby justifying the colonizing projects of the British Empire.

And yet, in his footnotes, Bentham did break new ground in the thorny terrain of human rights discourse. He pointed to the French, who, through Louis XIV’s code noir, embraced the idea that “the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor.”11 This staked a claim – a puny claim, but an important one – for the bodily integrity of the enslaved. Building upon this idea of the “humane” treatment of slaves, Bentham also lobbied for animal rights. He justified rights for animals by arguing that an ability to suffer, rather than to reason or speak, should be the barometer of how one sentient being treats another.

To be ethical, for Bentham, meant to treat sentient beings – that is, beings like oneself, that suffer – with restraint. In attempting to prove both slaves’ and animals’ rights, he asked, “The question is not, Can they reason? Nor, Can they talk? But, Can they suffer?” Acknowledging fully the deeply problematic nature of this specific move – the way it likens slaves to animals, leads to testimonial demonstrations of torment, and fails to recognize the violence embedded in the law – one can simultaneously note its efficacy in spurring protections against bodily harm.12

Despite ranking all human beings into various categories of sensibility, then, Bentham established the grounds on which bodily integrity would be argued in the courts, and he also linked anti-slavery, animal rights, and (implicitly Christian) suffering with Hinduism in ways that permeated female abolitionists’ performances. He noted that Hinduism, unlike Christianity, fostered the ethical treatment of non-human subjects such as animals.13

Abolitionists took advantage of this aspect of Bentham’s thought: they renamed Smith’s sympathy “metempsychosis” to remind themselves and their audiences of the precariousness of their own situations, the fluidity of interconnectedness, the fleeting nature of a fragmented identity, and the fact that one’s treatment of others could boomerang to oneself.

In a devastating move, Dugald Stewart (1753–1828) in 1793 built upon Bentham’s assumptions about rank to transform fellow feeling from a physiological, soul-based, or more reasonable “sympathetic” responsiveness into the class-bound, passive practice of “benevolence.”14 The more neutral performance of sympathy among parts is fully transformed in Stewart into a hierarchical system in which well-situated individuals, “naturally” aware of right and wrong, feel morally obligated to offer “pity to the distressed.”15 But in Stewart’s philosophy, unlike Smith’s, humans are not born with a corresponding impulse toward self-judgment or justice; in fact, their reason prompts them to “withdraw . . . from the sight of those distresses which stronger claims forbid us to relieve” and “to deny ourselves that exquisite luxury which arises from the exercise of humanity.”16

An involuntary correspondence among humans that leads to a desire to redress grievances is transformed in Stewart into a sympathetic practice that the well-to-do quite reasonably and routinely ignore, despite a feeling of obligation. Bentham and Stewart recast the emotional practices of the earlier eighteenth century in ways that the most radical of the abolitionists abhorred. Activists fought against Bentham’s and Stewart’s theories in part by recuperating and redirecting some – but importantly not all – of the elements of the practice of sympathy outlined by Adam Smith earlier in the eighteenth century.

In the mainstream press that many female Garrisonians detested, early nineteenth-century political theorists built upon Smith’s theories of moral sentiment and Stewart’s concept of benevolence to argue that democracies depended upon a particular kind of sympathy. Each United States subject was responsible for identifying with others’ suffering, so that a union among diverse subjects could be forged. Born-again Christianity became central to this process, providing a model for suffering: citizens sympathized with the tortured body of Christ, and the greater the imaginary suffering, the greater the Christian redemption and the stronger the nation.

A particular concept of freedom is embedded within this anti-Garrisonian notion of Christian suffering and redemption: in fact, the Latin redemptio signifies being purchased out of slavery, being freed. This freedom meant, as Orlando Patterson explains, “the valorization of liberation or release from the power or control of another agent,” “the power to do what one wants,” and the power to share “in the public or communal power of one’s society.”17 In Patterson’s view, this unique linkage of religion and freedom through “redemption” drifted into Enlightenment rationales of governance and through them into the present-day arrangements of the state. This model of suffering and redemption also emerged as an aesthetic model: Edmund Burke argued that watching torture was a source of the sublime because it evoked the strongest possible emotions.

Evangelical and mainstream Christians held that women were particularly gifted at sympathetic identification, and that through their embodied, imaginative suffering a diverse nation could be forged into a unified one. As Cornelia Wells Walter (1813?–1898), a Bostonian newspaper editor and cultural commentator, explained, woman “was a solvent powerful to reconcile all heterogeneous persons into one society: like air or water, an element of such a great range of affinities that it combines readily with a thousand substances.” Through their suffering, sympathy, and fluid sense of themselves, women could negotiate difference and aggression within the budding nation and encourage sympathetic desire in its place. Their suffering bodies could create an evangelical Christian nation. This national project was so important that men were encouraged to become more like women in terms of sympathy; men’s fashion wardrobes even began to include corsets, so that their very bodies would more closely resemble women’s. Free black publications fostered this idea of womanhood as much as white ones, though the mainstream idea of the nation was implicitly white.18

Within this evangelical sympathetic nation-building, agency and subordination were dangerously intertwined: “‘benevolent’ caretaking” and “‘willing’ dependency” were often linked in a web sustaining capitalist democracy. Full citizens sympathized with and governed willing but partial citizens. These partial citizens tried to perform their humanity and their right to inclusion in body politic by sympathizing with those enduring greater suffering. Becoming a civilized citizen, then, meant embracing sympathetic desire instead of exercising a direct and aggressive power over others. Women’s bodies were poised to create this sympathetic, loving sameness that would establish American unity through what Lori Merish calls “sentimental ownership.” This practice habituated national subjects to various forms of ownership, including slavery and coverture, and it fueled capitalism by encouraging women to create their identities through consumerism at annual fundraising fairs.19

And yet, economists were beginning to discuss the financial drawbacks of a forced labor system embedded in slavery. As Steven Mintz explains, in Wealth of Nations (1776) Smith had argued that slavery was “economically inefficient” and “instilled a contempt for labor, a love of luxury, and a lust for domination.”20 This rationale for ending slavery and instituting wage labor in its place received widespread attention as abolitionist societies emerged. Between 1832 and 1834 abolitionist Harriet Martineau, to name just one anti-slavery advocate who heeded Smith’s logic, published thirty-four stories illustrating various contexts for “free” labor. These stories were widely read and admired, especially by those who styled themselves educated women. For instance, in her journal Louisa Lee Waterhouse (baptized 1772, d. 1863), wife of Harvard physician Benjamin Waterhouse (1754–1846), recorded a scene in which she taught her husband about wage labor and political economy through Martineau. She identifies her husband as “Dr.” and herself as “Mrs.” in the recreated dialogue, which closely resembles the anti-slavery “conversations” published a few years earlier in The Genius of Universal Emancipation and the Liberator. When Dr. Waterhouse admits in the course of an after-dinner conversation that he “could not explain Political Economy” despite reading Martineau, his wife gently corrects his idea that “money is the root of all evil” and teaches him instead that it is “a species of wealth, with which you may purchase even other species of wealth.” “Its aim,” she continues in her dramatic dialogue, “is to find out the best means of preserving & augmenting the nation’s wealth” by considering “the arrangements betwe(e)n Operatives & Capitalists.” Mrs. Waterhouse concludes by sharing a professorial overview with her husband: “Adam Smith wrote on the subject, under the head of Wealth of Nations. I(t) is now discussed under the head of Political Economy, & [has] become in a degree fashionable & interesting from Miss Martineau [sic] happy illustrations.”21 In this little domestic scene, the wife teaches the husband that carefully managed capitalism is the path toward a nation’s brightest future, and free enterprise, predicated upon individual wages and “freedom,” is a key to its success.

Performing free labor

Free labor’s purported glories, in fact, had already launched disparate anti-slavery initiatives, including a free produce movement within Wilmington, Baltimore, and Philadelphia’s Quaker communities and a capitalist farming scheme devised by gradual abolitionist and transplanted Scotswoman Frances Wright. These early initiatives signaled the serious limits of performing anti-slavery through reworkings of capitalism: slave produce boycotts had a limited effect, and Fanny Wright’s experiment in creating free laborers out of enslaved farm laborers in Tennessee failed utterly. However, the free produce movement did make Northerners aware of their complicity in Southern slavery, launch consumer activism in the United States, and teach leadership skills to women who later spearheaded female anti-slavery societies.22 It also enabled women to collaborate interracially. And Fanny Wright’s effort to merge gradual abolitionism with capitalist goals, disastrous as it was, provided women with a cautionary tale and catapulted them onto the anti-slavery stage with a keen awareness of the pitfalls of public performance.

Imagining a populace as much dedicated to austerity and conscience as themselves, early free produce advocates boycotted slave goods such as cotton, tobacco, and sugar and instead purchased only agricultural products grown through free labor. Their goal was to force slaveholders to realize that, as Adam Smith had argued, slavery was economically impractical. Elizabeth Chandler compared “slave produce” boycotts, which educated townsfolk about the “enormities of the slave system,” with colonial women’s tea boycotts, which warned patriots about British imperialism.23 Philadelphia often led the way in the boycotts, partly because of its large Quaker and free black populations. Not only was Philadelphia’s free black community larger than that of any other northern city in 1830, numbering around 15,000 people (a little less than 10 percent of the population), but it also boasted an “aggregate wealth of . . . $977,500,” most of it attached to the top 1,000 earners: this translated into an upwardly mobile, visible, and visibly growing group of “Afro-Americans who seemed to differ from upper-class whites only in the incidental aspect of color.”24 In 1829, just two years after men organized free produce associations in Philadelphia, Lucretia Mott and Mary Grew formed the first Female Association for Promoting the Manufacture and Use of Free Cotton. Within a year black and white Friends – Mott, Grew, Chandler, and Sarah Douglass among them – met and shopped together at Lydia White’s free produce store at 86 North Fifth Street. Women across the Northeast and Midwest gained important administrative as well as business skills in this consumer boycott: for instance, the Secretary of the Colored Female Free Produce Society sent detailed formal minutes to The Genius of Universal Emancipation, whose editor published them “partly to inform our white friends of the regular manner in which they transact their business.” Although free produce societies were typically segregated, as early as May 1831 Philadelphian women began to visit one another’s free cotton meetings, networking across racial lines and evincing “manifestations of reciprocal good feeling” that spilled over into the anti-slavery movement.25

By altering consumers’ habits in the North, free produce advocates tried to prove that Southern slavery was not profitable, but Frances Wright took a different tack. Starting in 1825, Wright, a Scotswoman steeped in Enlightenment moral philosophy, tried to demonstrate how to end slavery gradually through a free enterprise scheme. Well educated, idealistic, and in full possession of her estate, Wright fell in love with the idea of the American republic. During her first visit to the United States, she produced a play extolling republics. She traveled widely, writing celebratory letters that she later published as Views of Society and Manners in America (1821).26 Garrisonians regarded this book as naïve at best and dangerous at worst, because it lauded American democracy without qualification.

On a return visit to the United States in 1824, however, Wright witnessed slavery firsthand and quickly joined abolitionist ranks – albeit as a gradualist, colonizationist, and global capitalist. She developed her Plan for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in the United States without Danger or Loss to the Citizens of the South (Reference Wright1825) from the margins of the utopian culture of New Harmony, Indiana. Hoping to demonstrate how plantation owners could move toward a free labor that would perfect America and compete successfully with free labor in the East Indies and South America, Wright purchased slaves and settled them on “Nashoba,” a Tennessee farm. There, “all colors” were to be “equal in rank” and slaves could, within a prescribed number of years, earn their own freedom while attending school and preparing themselves for an independent future in a foreign country.27 Wright incorporated colonization as a “necessary” concession to political expediency, but argued that race prejudice was not natural: in fact, she viewed gradual “amalgamation” as the solution to slavery. Her Nashoba experiment was a financial, social, and moral disaster. Wright’s illness and subsequent absence, her sister’s public disavowal of the institution of marriage, her Scottish overseer’s openly defended cohabitation with a “quadroon” – and her horrifying failure to protect female slaves from sexual abuse and hunger – sealed Nashoba’s fate. She freed Nashoba’s thirty slaves, resettling them in Haiti. Thereafter, Fanny Wright was associated with blackness, amalgamation, and free love, but that did not deter her. After observing the frenzied backlash following Nashoba and the feverish revivals of the Second Great Awakening, Wright decided that “American negro slavery is but one form of the same evils which pervade the whole frame of human society . . . it has its source in ignorance.”28 Only a rational education, Wright concluded, could eradicate the ignorance at the root of America’s ills, including slavery.

Accordingly, starting in 1828 in Cincinnati, Wright delivered a series of public lectures on reason, to mixed audiences of men and women, blacks and whites. Everywhere she traveled, audiences associated her with abolition and “amalgamation,” even when she did not speak of either. Through her lectures, she advocated freedom writ large: freedom for slaves and women, free public education, a free press, and freedom from religion. She presented herself as a rational alternative to evangelical “ravings of zeal without knowledge,” charging that “the victims of this odious experiment on human credulity and nervous weakness, were invariably women.” Excoriating the “ineptness” of the press, she championed workers’ rights and envisioned an equal citizenry shaped through public schools that would be run as boardinghouse orphanages.29

At the very moment when individual white men began to test the possibilities of blackface minstrelsy in American theatres, then, Fanny Wright took on the “blackened” body that the press had given her, stood on the stages of many of the same theatres, and lectured. When churches, town halls, courthouses, and theatres closed to her, she spoke with “uncommon powers” in the streets, often to the working-class male audiences of minstrelsy as well as the respectable classes, including women.30 By January 1829 she drew crowds of two thousand spectators in New York’s Masonic Hall and in the upscale Park Theatre, which housed her lectures as well as a revival of her play Altorf. Her decision to appear as a public speaker shocked audiences and stoked their curiosity.

This was an important step for women, because if they could lambast slavery in front of a live audience, they could manipulate the performance situation in various ways: they could adjust to disparate audiences by gauging the house’s response to them, moment by moment. They could draw on the emotional excitement created by a large crowd, building a reform movement. And within abolitionist-only gatherings, they could engage in effective self-judgment by listening to diverse activists’ appraisals of their statements.

Wright’s first lectures, however, did not provide a useful performance model. Speaking in her own “masculine” person without a sponsoring host to protect her, Wright stood curiously alone, despite the twelve to forty male and female friends who typically ushered her onto the stage and the crowds that flocked to hear her speak. While she was “eloquent, bold and enthusiastic,” she was haunted by her brush with slaves: her hands struck some as “neither very white, nor well-turned, nor lady-like.” In these lectures and in those that followed across the East, Midwest, and South over subsequent years, Wright demonstrated the dangers of not adapting mainstream practices such as sympathy. Rejecting not only the Constitution and all forms of Christianity but also any notion of sympathy, Wright appealed to audiences through a call toward observable truths, in “the utter absence” of any “womanly sensibility.” Sometimes opening with a performance of the Declaration of Independence as her “Bible,” she warned audiences: “I am no Christian . . . I am but a member of the human family, and would accept of truth by whomsoever offered.”31 In an effort “to turn our churches into halls of science,” she transformed a Bowery church into a lecture hall. By linking abolition, woman’s rights, and labor issues together as she spoke, Wright imagined a broader coalition than later activists. Her newspaper, the Free Enquirer, edited with Robert Dale Owen (1801–1877), attracted the Working Men’s Party, which became known, derisively in many circles, as the “Fanny Wright ticket.”

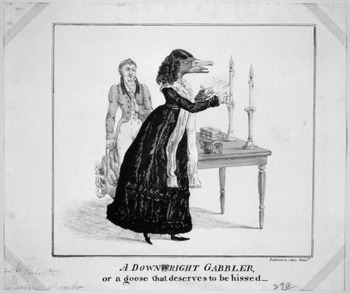

Wright tried to perform as a rational American, outside of the realm of evangelical sympathy, but her experiment failed in part because Americans did not associate a woman’s body with rationality and in part because they were wedded to sympathy. Even a balanced journalist such as the reporter for The New-England Galaxy and United States Literary Advertiser, who admitted that detractors who had not yet heard Wright speak would be “disappointed at first . . . in finding them of a higher style and less offensive and shocking in the language and more exterior manner, than they had expected,” dismissed her lectures as “mere flummery, too shallow and frothy to deserve or need refutation.” Less sanguine journalists read Wright through a pornographic lens, dismissed her as a “harlot,” or blackened her as a silly goose (see Figure 1). Her working-class followers, and even commentators like Walt Whitman, who genuinely admired her critique of labor conditions, could not stem the attacks on her character or the (often physical) attempts to silence her.32

1 J[ames] Akin, “A Downright Gabbler, or a Goose that Deserves to be Hissed.” Caricature of Frances Wright, Philadelphia, 1829.

A single example of these attacks must suffice here, to suggest the cultural anxiety that her abolitionist performances generated. William Leete Stone, editor of the New York Commercial Advertiser, covered her New York lectures in 1829, at first applauding her oratorical and acting skills, but quickly dismissing “her pestilent doctrines, and her deluded followers, who are as much to be pitied, as their priestess is to be despised.” Stone called her “a bold blasphemer, and a voluptuous preacher of licentiousness,” who, “casting off all restraint,” wanted to “reduce the world to one grand theatre of vice and sensuality.”33 By the time Wright delivered her fifth lecture in this series, she was physically attacked: a detractor burned a barrel of turpentine at the entrance to the hall, creating havoc and jeopardizing the lives of all those who dared to attend her talk.

Nonetheless, Wright’s early public lectures to racially diverse audiences of men and women inspired abolitionists and workers across the country.34 She provided a model of tenacity if not ideology or strategy for Garrisonian speakers, who learned from her reception that however much they might agree with her critique of evangelical suffering as the path toward citizenship or her critique of labor practices, they could not ignore the power of mainstream sympathy. They needed to organize sponsoring agencies within which they could radically revise and redirect fellow feeling as well as reason. But how could they revise the performance of sympathy to their own ends? That is where Adam Smith reentered the scene.

Adam Smith’s sympathy

In The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Adam Smith argued that reason alone is insufficient to prompt ethical action; moral judgment – particularly moral action – also requires emotional engagement.35 Smith explained how the multi-step performance of sympathy could lead to ethical behavior as well as nation-building. Anti-slavery women could see the limits of both Smith’s sympathy and his concept of nation-building, though they did not initially perceive the extent to which “free labor” led to the excesses of free-market capitalism.

While Hume examined the ways in which individuals respond sympathetically to others’ emotions, Adam Smith, quite usefully in the Garrisonian abolitionists’ estimation, focused instead on how humans respond sympathetically to each others’ circumstances in order to initiate ethical behavior. This shift from a mechanistic, passion-based focus on the emotions (so comfortable for evangelicals in the Tappanite wing of the anti-slavery movement) to a reason-based consideration of the “cause and context” of the situation (more likely to surface among Garrisonians) is key to understanding what the latter were trying to perform as they shared activist conversations, dramatic dialogues, poems, songs, and plays. Focused on the circumstances causing the slaves’ pain, anger, or joy, they hoped to prompt a corresponding critical feeling and self-judgment in their spectators. Importantly, in Smith’s view and in theirs, that emotion might not resemble the feelings of the slaves themselves.

No one can directly inhabit someone else’s body, Smith recognized, and so he argued that what one feels as a result of sympathy is one’s own emotion. In Smith’s scenario, “I consider what I should suffer if I was really you, and I not only change circumstances with you, but I change persons and characters” with you.36 The spectator’s feelings are not those of the sufferer but of the spectatorial “I,” and the self never encompasses the other, but only acts as if she has exchanged “circumstances” with the person in pain. Garrisonians did not think it possible to grasp fully each other’s feelings, let alone the slave’s. They did, however, see the task of many actors – performing as if one finds oneself in someone else’s material circumstances – as a key to anti-racist, anti-slavery activism. This meant finding out exactly what the material circumstances of slaves and free blacks across the South and North were – without reducing blacks to that materiality.

The first step in Smith’s performance of sympathy, central to Garrisonian practice, entailed the spectator’s trying to imagine herself in the other’s circumstances, though “our senses . . . never did, and never can, carry us beyond our own person, and it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations.” By emphasizing the imaginative effort to grasp “any” idea at all of others’ feelings, Smith and his followers emphasized the difficulty and limited success of that effort. Without an “immediate experience of what other men feel,” Smith cautioned, “we can form no idea of the manner in which they are affected, but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation.”37 The feelings one experiences are one’s own.

Smith continues, still emphasizing the limits of sympathetic practice: “By the imagination we place ourselves in his situation, we conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body, and become in some measure the same person with him, and thence form some idea of his sensations, and even feel something which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them.” Again, in this passage Smith stresses the imaginative effort to recreate not the other’s feeling but the other’s “situation.” He focuses on the individual’s effort to undergo the conditions, “as it were,” of the sufferer, but he emphasizes that that happens only “in some measure” and is “weaker in degree.” And the emotion felt is one’s own.38

Smith is keenly aware of the cultural differences in how individuals perform emotions, and though he calls non-Europeans “savages and barbarians” and represents their stoicism as nearly incomprehensible to Westerners, as Foster notes, he also clearly regards it as admirable: “there is not a negro from the coast of Africa who does not, in this respect, possess a degree of magnanimity which the soul of his sordid master is too often scarce capable of conceiving.”39 To possess magnanimity meant to have a “well-founded high regard for oneself manifesting as generosity of spirit and equanimity in the face of trouble,” as well as “greatness of thought or purpose; grandeur or nobility of designs, ambition, or spirit.” Smith contrasts this admirable magnanimity of “those nations of heroes” with the “brutality and baseness” of their European jailers, “wretches” who possessed no virtues at all.40

Others’ “agonies, when they are thus brought home to ourselves, when we have thus adopted and made them our own,” Smith continues in his analysis of sympathetic practice, “begin at last to affect us, and we then tremble and shudder at the thought of what he feels.” However, even when one’s body responds physically to the sympathetic tug, one feels only to a certain extent, for to imagine another’s pain “excites some degree of the same emotion, in proportion to the vivacity or dul[l]ness of the conception.”41 Smith’s delimiting words and phrases emphasize the difficulty, not the ease, of sensing someone else’s circumstances. This stress on the disjunction of feelings between abolitionists and imagined or real slaves deserves further attention.

Smith usefully limited the claims of this first step in the practice of sympathy. He did not see pain as “an experience which cannot be recovered by the victim but only by the spectator.”42 In fact, he viewed the spectator’s engagement as limited in a host of ways, and abolitionists like Sarah Forten acknowledged those limits in poems like “Past Joys”: black abolitionists in Philadelphia read her poem aloud to one another, publically acknowledging that the slave’s suffering “is a sorrow deeper far, / Than all that we can show.”43

In fact, Smith compares a sympathetic witness to another’s pain to a man’s witnessing a woman give birth: the man imagines the woman’s pain “though it is impossible that he should conceive himself as suffering her pains in his own proper person and character.” He cannot himself give birth, but must do his best to imagine what he would feel if he were in her circumstances. He cannot presume that he knows her feelings, because his feelings will, of necessity, be his own, and they will differ from hers, but they will be real, embodied feelings and they will activate him to alleviate her pain as best he can. Jeremy Bentham, who ranked people on the grid of sensibility, claimed that elite men felt more exquisitely than, say, women or slaves, and, focusing on this scene of human difference, he justified the act of colonizing them, but female Garrisonians revised this first step of sympathy, to try to derail its use within the processes of colonization.44 They focused audiences instead on the man-made “cause and context” of the slave’s injury or his resistance to that injury, enabling others to see the similarities as well as differences among persons inhabiting disparate circumstances.

As Elizabeth B. Clark demonstrates, radicals usefully redefined pain as stemming from a human breach rather than a divine act, thereby establishing a cultural basis for legal reasoning by analogy.45 There are limits to this accomplishment, as Berlant and Allen Feldman and others have shown: establishing a violent scene as the prompt for redressing human rights abuses curiously instates the legal, medical, and governmental apparatus as “post-violent,” presuming it to be benign, even protective, and then publically displayed suffering becomes necessary to authenticate abuse.46 But Garrisonian women revealed how this process worked: they refused to recognize the state as “post-violent.” They unveiled the mechanisms of legal power, named their own complicity, and worked to dismantle the laws that upheld slavery. The question of abolitionists’ culpability for forging a “free” but encumbered citizenry often surfaces in abolitionist scholarship: Spelman, Merish, and Sanchez-Eppler, for example, argue that sentimental attachments to the slave’s pain “reinforce the very patterns of economic and political subordination responsible for such suffering,” and Hartman explains how slaves came to be held responsible for their own rehabilitation through the “blameworthiness” of American individualism.47 Since Christianity anchors this notion of individual freedom, there is no space outside of complicity in this interwoven network.

One cannot ignore, however, the ways in which certain abolitionist performances, despite their coercive power, simultaneously and necessarily also created new, resistant, and even institutionally productive pathways through state-sponsored violence. Blending a radically revised Christian sympathy with Hindu metempsychosis, black and white Garrisonian women moved past Frances Wright’s individualism to create a real sense of emergency and hold the state responsible for the depredations of slavery – even as they collectively championed their outlier status.

After abolitionists imagined themselves in slaves’ circumstances, they tackled Smith’s second step to performing sympathy. In this step, the spectator and the one witnessed adjust to one another: the spectator raises her level of concern and the individual who feels joy or pain lowers her passion to the spectator’s pitch.48 Slaves were not physically present within early female anti-slavery society gatherings, but the same principle pertained: black and white women tried to “excite” themselves to a higher level of engagement and simultaneously tempered their imaginings of the slaves’ circumstances. This meant, of course, that when fugitive slaves escaped North, they had to negotiate through abolitionists’ muddled images of their material circumstances. Similarly, though, it meant that women had to keep raising their level of activism to reach the expectations of the newly freed.

The final step in Smith’s sympathetic practice is that the sympathizer imagines how an “impartial spectator” would evaluate his or her behavioral response to the person in distress or pleasure. In Smith’s view, we cannot judge our actions “unless we remove ourselves, as it were, from our own natural station, and endeavour to view them as at a certain distance from us.” We regard our behaviors as others of a different “station” or class “are likely to view them.”49 Although the well-educated Unitarian and Quaker women in the free produce and anti-slavery movements may have encountered Smith’s views in Dugald Stewart’s widely circulated 1822 edition of Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, they rejected Stewart’s effort to transform an active sympathy into a passive benevolence, partly by rejecting his gloss of this critical passage in Smith. Stewart refers to the impartial spectator as “mankind in general,” but for immediate abolitionists the spectator who judged their actions was a specific someone of a different “station”: a slave. Over and over again, Garrisonian women imagined slaves’ passing judgment on them. For them, the passage “we endeavour to examine our own conduct as we imagine any other fair and impartial spectator would examine it” meant judging one’s own behavior through the eyes of slaves, or, sometimes, through the eyes of a fiercer, more radical version of themselves.50 Their spectator, in fact, was a partisan rather than an impartial onlooker.

In Smith, spectators find fellow feeling “most accurate” when the sympathizer, in this case the abolitionist, “is conscious of the possibility of mistakes.” This consciousness of mistakes emerges as “inappropriate moral judgments are corrected by the community in conjunction with the moral actor him or herself.”51 As women performed their sympathy with the slave, then, they became conscious of missteps and corrected their judgments about proper moral actions in response to more radical members’ assessments. As they reached outside the abolitionist community through their “conversations” and dramatic dialogues, they extended the reach of this readjustment process, encouraging neighbors and townsfolk to correct their own mistaken judgments about how to act with regard to slavery.

This critical aspect of sympathy became more important to Smith over the years: in his fourth edition, he added to his title (The Theory of Moral Sentiments) the subtitle or An Essay towards an Analysis of the Principles by which Men Naturally Judge Concerning the Conduct and Character, First of Their Neighbours [sic], and Afterwards of Themselves. Only when the impartial spectator (in abolitionists’ adaptation of Smith, the partisan spectator, the slave) validates the sympathizer’s actions can he or she feel virtuous, according to Smith, so this self-judgment through the eyes of the slave paves the way to a sense of virtue and, eventually, a more expansive love of oneself, which deepens into a love of others. The trick for abolitionists was to avoid an inflated sense of virtue.

Garrisonians still had to contend with the fact that humans tend to feel the most for themselves or for those with whom they already share a connection, so that “the misery of one who is merely their fellow creature is of so little importance to them in comparison even of a small conveniency of their own.”52 However, over time and with practice, Smith contended and abolitionists hoped, most people gain enough information about the varied circumstances in which people live that they improve at sympathizing with others and recognizing their full humanity.

Yet, there are some people – and Adam Smith counted slave-owners among them – who are “insensible to all appeals of humanity” and who “fall outside the sphere of ethical conversation”; the state must intervene to thwart their immoral actions, Smith argued, or – if they are themselves the lawmakers – a rebellion must be launched.53 Garrisonian abolitionists imagined themselves in the throes of such a rebellion. They understood that the violence was embedded within Constitutional law and that slaveholders, at least those who held out against anti-slavery practices, were so “insensible” that a civil war might be necessary.

Sympathy is not empathy

The cluster of practices that comprise “empathy” were unknown to early nineteenth-century black and white abolitionists, but they have, rightfully, created uneasiness among present-day scholars about any circulation of affect. Exorcizing the confusion about the disparate genealogies moving from sympathy to empathy may aid in formulating new practices as well as clarify why sympathy cannot simply be collapsed into empathy in scholarly investigations of abolitionism. Though English psychologist Edward Titchener first translated Einfühlung as “empathy” in 1909, this German term, Einfühlung, had surfaced earlier, in 1873, when art historian Robert Vischer (1847–1933) had used it to describe the way in which viewers projected themselves into art objects.54 Beauty was not inherent in the art object, Vischer argued, but rather an effect of the museum-goers’ projections of themselves into the object. Here the relationship between the spectator and the other is reduced to a projection of the self onto an object, and the value of the interaction is not political action but the resignification of the viewer (instead of the artist) as the one who creates beauty. English critic Violet Paget (1856–1935), known by her pseudonym Vernon Lee, created havoc when she translated Einfühlung into English as “sympathy” in 1895, associating it with Titchener’s idea of a spectator’s projection onto an object and the lively sense we have “when our feelings enter, and are absorbed into, the form we perceive.”55 Lee not only moved a radically altered notion of sympathy into the artistic arena, but also introduced the idea of motor mimicry. She explained that museum-goers responded physically as well as emotionally to art objects, standing tall in response to Greek columns, for instance. German philosopher Theodor Lipps (1851–1914) then transferred Einfühlung from aesthetic to psychological discourse in 1903, arguing that viewers who see someone engage in an angry gesture, for example, not only mirror that gesture but also project themselves into the gesture. In these rewritings of sympathy into empathy, viewers project their very “selves” into art objects or isolated gestures and thereby gain access to beauty or self-knowledge.

In other words, sympathy, in Smith’s hands an effort to grasp someone else’s circumstances in order to build a responsive if hierarchical community, and in female abolitionists’ hands an imperfect effort to grasp the material circumstances of the slave in order to judge oneself through the slave’s eyes and build a responsive and more democratic community, transforms from a two-way street into a one-way process as it morphs into empathy.

The attendant dangers within this one-way empathetic practice – the dangers of projecting the self onto the other, of appropriating the other’s pain as if one has mastered it fully, and of subjecting the other to that mastery and voyeurism – are serious. Theorists immediately began to forge pathways through these dangers, even as they created others more worrisome. In 1909, Titchener built on Lipps’s theory, translating Einfühlung as “empathy” and describing it as an involuntary kinesthetic response, built upon real or remembered sensations. This usefully restored some of the two-way sensibility present in earlier theories of sympathy, and granted more power to the sufferer by defining empathy as an imitative and motor response to the one in pain. Titchener’s approach, however, dismantled Smith’s useful limits on fellow feeling by arguing that empathy enabled one to access another person’s consciousness.56 And he returned to Bentham’s earlier hierarchical system of sensibility, envisioning that empathy created a community of discriminating judgment, a “freemasonry among all men and women who have at any time really judged”: his theory thereby echoed Bentham’s earlier claim that “sensibility appears to be greater in the higher ranks of men than in the lower.”57 As Titchener’s empathy drifts into the twenty-first century, it is likely to be attached not to upper-class sensibility, but rather to individual personality and context: “the effect and degree of empathy varies according to individual predilection and personal interaction.”58 The route to this focus on individualism was circuitous.

In 1917 Edith Stein (1891–1942), a student of Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), usefully transferred the concept of empathy into the arena of phenomenology, grounding it in experiential knowledge and offering useful corollaries to Enlightenment notions of sympathy and antidotes to some of Titchener’s excesses. Like her mentor, Stein did not argue that the self merged with the other. Rejecting Titchener’s and Lipps’s lead, Husserl had contended, as Krasner explains, that “we are individuals encased in our own consciousness,” but that “in communicating and living in the world with others[,] we experience . . . ‘intersubjectivity’ . . . mediated through empathy.”59 Merleau-Ponty and Emmanuel Levinas circumvented Husserl’s “self-enclosed ego” by articulating an “embodied approach to intersubjectivity” that has received widespread attention, while the lesser-known Stein forged her own understanding of how empathy surfaced.

Stein defined empathy as both the comprehension and “experience of foreign consciousness,” but, like Smith and the abolitionists, contended that the “self” did not merge with the other. In fact, the self was aware of the other as someone with his or her own phenomenological experience of the world.60 Furthermore, empathy for Stein could only be the “non-primordial” or second-hand experience of the spectator which “announces” a “primordial” or firsthand experience through which the other person has lived.61 Gone is Adam Smith’s clarifying two-way awareness and adjustment; this is an emotional exchange which is viewed only from the point of view of the spectator, but, as in Smith and in abolitionist practice, there is a recognition that the one who witnesses suffering or joy does not experience the exact emotion that the sufferer or celebrant does. Stein’s witness, even in a situation of strong empathy, was always aware of what she called the “foreign psychic I,” but was also capable of creating a fluid, temporary “we” that retained individual mystery and difference.62 Stein, then, with Husserl as her foundation, solved some of the thorny problems of empathy that Bertolt Brecht, famously, later tried to solve through his “alienation effect,” a defamiliarization of the structures of power solidified through empathy.

Performing metempsychosis disparately

Female abolitionists did not perform this twentieth-century empathy, nor did they perform eighteenth-century sympathy: in fact, they ridiculed ladies and gentlemen who merely read sentimental tales of slaves’ suffering or Romantic-era poems about the slaves. In the abolitionist newspaper The Genius of Universal Emancipation, a satirist mocked a certain sentimental lady of this sort, comparing her sympathizing to the self-indulgent pastime of bowling: “Down Clara’s cheek the precious globules hop; / How beautiful, the precious fluid rolls; / There goes a tear, there starts another drop, / As if her sympathy would play at bowls.” Even mainstream critics lambasted this self-indulgent type: “the morbidness of her sensibility is a bar to the real exercise . . . [she] shuts her eyes and closes her ears to genuine distress.”63 Abolitionists themselves were made of much sterner stuff.

In her February 1831 column for The Genius of Universal Emancipation, a young white Quaker named Elizabeth Chandler coined the phrase “mental metempsychosis” to describe the emerging sympathetic practice of abolitionists.64 She advised her female readers to imagine themselves, in detail, in slaves’ material circumstances rather than their feelings, to spur themselves and others into action. As she penned her column, the mainstream press was representing the slaveholder as the most visible “body in pain,” suffering from the weight of an inherited institution. Chandler replaced that figure with the slave, an equally feeling – and judging – figure, thereby contesting the slave’s place as the lowest entrant in Bentham’s list of sentient beings. Instead of representing blacks as savages, she represented American slaveholders as brutes. But first, Chandler and her black and white friends within the Garrisonian movement had to separate themselves from the evangelicals.

Within mainstream Calvinist thought and evangelical Tappanite abolitionism, pain results from divine will and echoes the crucifixion, thereby modeling Christian forbearance. The slaves are figured as the children of Ham, destined to suffer for their ancestors’ sins but free to stretch out their hands to their deliverer, God. In liberal religious terms, however, that pain is reframed: Garrisonian Unitarians and Hicksite Quakers created mental metempsychosis to revise the role of pain in the cultural imaginary. Pain, for them, was no longer the result of divine Providence, but the result of human actions.65

In fact, Garrisonians viewed suffering as a breach in God’s law, the result of a man-made Constitution that encoded violence against all but the controlling elite. The slave body in pain, then, figured human error. Through metempsychosis, these abolitionists established the legal rights of slaves by analogy, as Clark notes: the slave, like oneself, is fully human and deserves the same rights as other individuals, including the right to his or her own body.66 This meant lobbying for slaves’ freedom of movement, right to marry, right to refuse sex, right to be free of physical abuse. The practice of metempsychosis also usefully enabled practitioners to imagine across racial, gendered, sexual boundaries, to envision a “common blood.” By focusing on bodies as well as souls, anti-slavery advocates tried to combat the abstract personhood underpinning the privileges of white male property-owners and to dislodge morality from specious Biblical arguments so that all could return to rational judgment and individual feelings corrected by those once on the margins.

Even when they were imagining themselves as slaves, anti-slavery women were fueled by wildly disparate objectives, so they generated different effects. The working-class and middle-class mill girls of Lowell, Massachusetts, sympathized with the slaves for entirely different reasons than the urban elite of Boston: the former helped create an incipient labor movement and the latter a Unitarian stronghold of reason. In Boston, women’s disparate religious affiliations led to friction and distinct differences in how women understood what actually happened during public enactments of metempsychosis. Unitarians, for instance, chafed at any mention of a “triune God” and brusquely viewed their anti-slavery performances as the rational path toward a logical equality crafted by human beings, while Presbyterians, who balked at any mention of the free will so dear to Unitarians, valued the Trinity and joined Congregationalists to decry non-conformity in general and Unitarians in particular. The Presbyterians and Congregationalists simply wanted to save slaves’ souls in an orderly fashion while keeping women and others in place.

Then, as now, the performance customs of women from different religious denominations signaled disparate investments. The 1827 rift in the Quaker community meant that even Friends experienced metempsychosis disparately, with the Orthodox Friends anxious about the more radical Hicksites. Joining Unitarians, Hicksite Quakers rejected the crucifixion and the divinity of Christ (as well as the clergy) altogether: they wanted to sideline suffering within abolitionism. For Hicksites, sympathy with the slave was simply a reasonable, conscientious response to a man-made problem. Wary of the limits of one’s childhood traditions and focused on the practical duties of the “inner light,” Hicksites practiced anti-slavery as a rational act. In fact, both Quakers and Unitarians were wary of emotional excess. Because of their emphasis on religious “enthusiasm” or warmth, Methodists and Baptists connected most directly with the emotional component of performing sympathy with the slaves’ suffering. However, as they were often working-class or lower-middle-class, they were also very likely to be as interested in the material conditions of the slaves as they were in the status of their souls.

Even when black and white women collectively imagined themselves as slaves, then, they were embodying disparate investments through those performances. And spectators were experiencing different reactions even if they were applauding the same abolitionist speech, listening to the same poetry recitation, or acting in the same anti-slavery play. They were perceiving the “stickiness” of emotions as they impressed upon bodies, slid and moved bodies, differently. As Maria Weston Chapman explained of female abolitionists, their “common cause” surfaced in “different vesture[s]”: “One is striving to unbind a slave’s manacles, – another to secure to all human souls their inalienable rights.” Some wanted to convert slaves to their own denominations, while others labored so that “the bondman may have light and liberty to form a system for himself.” Some wanted slaves “to hallow the Sabbath day,” while others wanted them to “receive wages for the labor of the other six.”67

Anti-slavery conversations

Early free produce “conversations,” published in the abolitionist press and performed in homes, churches, and society meetings, set the stage for performances of metempsychosis. Instead of performing as slaves, however, the black and white women of the free produce movement initially cast themselves as inexperienced but eager abolitionists. They created a variety of characters, always judged by a partisan spectator figured as a more engaged, well-informed activist. In the ladies’ or juvenile departments of abolitionist newspapers, they published these “conversations” to prompt certain kinds of speech acts among black and white families fighting against slavery. Sometimes borrowed from British journals, these descriptions of a thoughtful family’s abolitionist conversations reveal that activists’ evenings were dedicated to political discussions engaging not only the young adults but also the youngest members of the family.

While the conversations modeled free produce and abolitionism, the slaves in these columns always lived in the West Indies or in the South rather than the North. There was no acknowledgment that many slave women were still fighting to gain their freedom in the 1820s in the Northeast.68 There was, instead, an attempt to foster family-based performances, to critique privilege through these performances, and to transform privileged black and white middle-class American families and boardinghouse tenants into abolitionist activists. Both The Genius of Universal Emancipation and the Liberator served black as well as white readers, so it is instructive to consider black families’ readings of these dialogues. Black leaders, Sarah Forten’s father among them, helped fund the Liberator at its inception, and by Reference Ada1834, fully three-fourths of its readers were drawn from the black community.69 Many of the homes in which these performances took place were well appointed: among black Philadelphians, for instance, parlors were “‘carpeted and furnished with sofas, sideboards, cardtables, mirrors . . . and in many instances, . . . a piano forte,’ where, in prearranged formal visits, black women trained in ‘painting, instrumental music, singing . . . and . . . ornamental needlework’ visited,” and “their men – home from concerts, lectures, or meetings of literary, debating, and library association gatherings at their meeting halls – sometimes joined their women.”70

In 1831, Elizabeth Chandler published a column specifically titled “Conversation,” outlining how she hoped these family dialogues would not only energize participants but also prompt them to extend their efforts outside their homes, churches, and boardinghouses. Her column and those like it were read aloud at gatherings of different kinds, not just at literary society meetings but also in family homes, taverns, and lodges. To legitimize her column, Chandler prefaced it with John Milton’s warning that “Man over man, He made not lord.” She then touted the virtues of “frequent conversation” about anti-slavery: converts might “find their feelings still more deeply engaged,” while the uninitiated or recalcitrant would discover that anti-slavery conversations “open the door to an instructive discourse, awaken the dormant sensibilities, and perhaps arouse into action.”71

Noting that William Cowper (1731–1800) renamed his indictment of slavery “A Subject for Conversation [and Reflection] at the Tea-Table,” Chandler highlighted improvisational dialogue in mobile social settings. Each theatrically modeled dialogue prepares the listener “to receive, with attention, any future information relative to the system.” As Chandler advised, “it is better to risk the mortification of being listened to with repulsive coldness, than to fail of using every proper exertion.” In fact, Chandler argued that abstaining from slave produce was crucial because it fostered ever-changing conversations about anti-slavery.

Through these “conversations,” parents transformed their children and neighbors into activists, all the while entertaining them. In a typical Liberator “Conversation” published on September 24, Reference Ada1831, parents taught their young daughter Emma that West Indian planters had no right to enslave Africans.72 Imagine a black family gathered in a rural Pennsylvania parlor, reading an abolitionist “Conversation” aloud, in keeping with nineteenth-century customs. The mother assumes the role of Mother, a reasonable abolitionist who believes that West Indian blacks, as “‘fellow subjects . . . ought to share in all our privileges.’” Perhaps her husband passes the newspaper around, inviting the older children to read the youthful roles, with distinct voices for different parts. In this “Conversation,” the fictional parents calmly request that their son avoid castigating his younger sister for her ignorance about abolitionism. Instead, they counsel him to inform her gently about the importance of anti-slavery, for then she will come more willingly into the abolitionist fold.73 The author of this “Conversation” offers a performance model that works not only within the family, but by extension with neighbors and townspeople. This is not a performance of sympathetic suffering with the slave, but a reasonable transformation of uninitiated citizens into activists.

In the fourth installment of this same “Conversation” series, reading the newspaper aloud is directly incorporated into theatrical representation as the family educates itself and its neighbors about the economics of slavery. Perhaps a white teenage sister and brother, joined by a visiting neighbor, performed this conversation for extended family on a breezy September evening in Salem, Massachusetts, circa 1831. The fictional older sister, Helen (played by the actual sister), tells her family that in buying West Indian sugar “we bribe the Planters . . . and make it worth their while to keep the Negroes in slavery.”74 Her father (played by the brother) concurs, reading statistics from the newspaper to prove that governmental bounties support the price of slave-produced sugar. As a result, free labor sugar cannot successfully compete with slave products. Sugar, the girlish Helen replies, is also taxed to pay the press for its pro-slavery coverage, “so that,” her fictional father continues, “when we buy West Indian sugar, we actually assist in stifling the cry of the oppressed.”

Having mapped out labor issues and the press’s complicity with business interests, the actress playing Helen recites for the family, as if from memory, an anti-slavery poem warning the English to end slavery in their own colonies before asking other Europeans nations to follow suit. At that moment her boyfriend George (played by the visiting neighbor, let’s say) enters and discloses that he and his father both own Jamaican plantations with hundreds of slaves. He tries to enlist Helen’s family to protest the anti-slavery meeting planned for the following evening, but the young white abolitionist girl portraying Helen in this “Conversation” models the appropriate response for those gathered around the parlor. She judges herself as a partisan spectator, a more radical abolitionist, might, and as a result rejects her beloved suitor George because of his bloody ties to West Indian plantations. And the rest of the family (played perhaps by parents and siblings) teaches the clueless neighbor–suitor George that inheriting slaves is no better than kidnapping them. George and his father will be, they promise, treated with respect at the anti-slavery meeting, but they do not deserve that respect, because they themselves are directly responsible for the horrors of slavery, including, Helen calmly and directly tells George before she flees from him, “scourging women.” Instead of imagining herself as one of the “scourged” slave women, Helen exemplifies an ever more committed anti-slavery advocate: she breaks off her engagement because of her anti-slavery views.

Anti-slavery dialogues

Eventually, these conversations about slavery transmogrified into longer dialogues, ready-made for performing within diverse family circles and neighborly social gatherings. Envision two middle-aged women, black or white, performing Chandler’s “Tea-Table Talk” dialogue in their family’s parlor after dinner on a wintry night in 1832. The dialogue stars two cousins, “Helen” and “Maria.” Spectators watch Maria, perched in her upholstered chair by a side table, complain about the silliness of Helen’s free produce activism, her “disagreeable” and “singular” practice of declining to eat “almost anything” offered to her.75 Helen tries to reason with Maria, adjusting her posture and patiently offering the political, spiritual, and ethical reasons for her free produce actions. In fact, as the rational Helen explains, “it is wonderful to me how any female, who has even a partial knowledge of the horrors, can be willing to support such a system, or can receive the least enjoyment from the indulgence in comforts and luxuries which are purchased by the sacrifice of so many lives.” The scene closes with the mature Helen’s unflappable economic analysis: “allowing the labor of a slave for six or twelve years to produce all the various slave grown products which you may use during the course of your life, would not he who was so occupied be in effect your slave, during the time he was thus employed?” By the curtain, the newly initiated Maria has just consumed a cup of tea without sugar and found that “it was not so very disagreeable” – though she is still not quite convinced that she must give up sugar every day. Helen has convinced Maria to move, gradually, toward anti-slavery activism. These polite but straightforward dialogues modeled how to alter others’ behavior gently but firmly. And the focus was upon the potential abolitionist, not the suffering slave.

As the free produce and immediate abolitionist movement gained ground and as American women read more about Englishwomen’s accomplishments, abolitionist dialogues championed British strategies. Months before female anti-slavery societies organized in the United States, female literary societies could read aloud “Edna’s” playlet in which American women, guided by the reports of the “Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society in England,” embraced activism and “private benevolence” instead of relying on Congress to end slavery.76 Encouraged to act by their “transatlantic coadjutants” in England and Scotland, “Aunt Mary” and her abolitionist friends suggest that American women follow British women’s leadership and divide “the laity” into districts, so that they can go door to door, petitioning others to join them in organizing anti-slavery societies. This is exactly what women did within their female anti-slavery societies in the 1830s.

Sometimes the objectives of abolitionist dialogues morphed as they unfolded. “A Dialogue between a Mother and Her Children,” for instance, opens as an anti-slavery tract and closes as a call for a college for free black youth. Picture a free black family in, say, Trenton, New Jersey, performing this playlet aloud on their porch on a Sunday afternoon just before school begins in the fall of 1832. The children perch on either side of their mother on the sofa. Signed “Zillah” and likely penned by free black Sarah Douglass from nearby Philadelphia, this drama depicts a mother as she teaches her son Henry and her daughter Matilda not to waste bread, a precious commodity among older slaves “freed” and forced to earn a living on their own. Upon hearing a sad story about an older slave, the youthful Henry decides to send his gift money to this slave, but his mother replies that the slave is no longer alive; Henry had best save his money and send it to those “now preparing to build a College for our youth.”77 In this instance, the black abolitionist mother embodies not only anti-slavery activism but also free black philanthropy, in this case placing the free black community’s needs ahead of the slave’s. This performance of what Sarah Douglass later called a “compassion for the self” became central to women’s abolitionism.

In the August and September Reference Edna1833 issues of The Genius of Universal Emancipation, Chandler reprinted question-and-answer dialogues tailor made for the new abolitionist-run Sunday schools springing up around urban areas. Written by Lucy Jesse Townsend (1781–1847), a leading English abolitionist, these dialogues taught, in a sort of abolitionist catechism, all the relevant Biblical passages lambasting slavery.78

Children’s plays appeared in the anti-slavery newspapers, too, ready-made for evening parlor performances. For example, “Aunt Margery” starred in a series of little dramas in the April and May 1832 issues of the Genius. This dramatic character, perhaps embodied by a mother or grandmother, taught children the importance of using maple sugar instead of slave-produced sugar, revealing how slaves were affected by American habits of consumption.

In October 1833, Chandler published an important dialogue that would have fit nicely into the programs of literary societies. In this “Dialogue on Slavery,” Rachel convinces Mary, a colonizationist, of the ease, safety, and justice of immediate abolition. She asks Mary to trust her own reason against the arguments of the anti-abolitionists and asks a series of deftly phrased rhetorical questions. For instance, imagine an abolitionist in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the winter of 1833, playing “Rachel” to her neighbor’s “Mary.” Mary voices concern over whether or not slaves will be able to survive within a free labor system, to which Rachel replies, “Will they who toil patiently for others, not labor for themselves?”79 Through this rhetorical question, Rachel refutes the argument that slaves would not be able to make the transition to a free labor market. When Mary, ever cautious, asks the more radical Rachel if she has heard “Dr. Porter’s opinion” on the matter, Rachel models womanly independence for young abolitionists by responding, “I have; but it has had no influence over my own.” She reminds Mary that even though slaveholders seem intransigent about slavery, their “sentiments may be changed.” She argues that women may as well work toward immediate abolition, since Southerners do not seem any more likely to embrace gradual abolition and “they must yield something to the public feeling.” By the end of the dialogue, the “actress” playing Rachel has convinced her neighbor Mary to join the ranks of immediate abolitionists, thereby providing a model of action for Chandler’s readers: the Genius itself was a latecomer to immediate abolition.

Metempsychosis in a state of emergency