Preface

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 April 2018

Summary

For much of the period before the end of the apartheid era the history of the South African press was the history of the white commercial press – the newspapers, magazines, and newsletters that were owned and controlled, produced, and consumed largely on behalf of those who ruled. And yet beneath the surface of this mainstream media lay hundreds of publications that sought to represent the anxieties and fears, interests and needs, hopes and desires of those who had no voice in white South Africa – the Africans, Coloureds and Indians who made up the vast majority of South Africa's population.

The first publications in African languages – produced by missionaries working in communities of Bantu-speaking Africans in the Northern and Eastern Cape – stem from 1836 or 1837. This was only 12 or 13 years after the first newspaper owned by a white colonist was published. For most of the period between the late 1830s and the early 1990s, however, the black non-commercial press, like the white commercial press, was a sectional press. Black publications were aimed at or intended for separate African, Coloured and Indian communities, just as the European community was the primary consumer of the mainstream white press.

The archive of periodicals representing these subaltern communities – arguably the oldest and largest in sub-Saharan Africa – was virtually unknown before the 1960s/70s, when a few scholars began to interview ordinary Africans who were not necessarily prominent politically, but had been active as church leaders, educators, journalists, literary authors, and businessmen and -women. These scholars were not so much interested in the publications where their African informants had expressed their views, but inevitably this entered into the conversation.

I shall never forget one of my first interviews, which was in 1964 with Gideon Sivetye at his home in Groutville, in the province of what was then called Natal. Sivetye was Chief Albert Luthuli's pastor, and Luthuli, president-general of the African National Congress (ANC), was then under virtual house arrest within a few hundred metres of where we were meeting. The South African authorities at the time had little interest in anonymous researchers meeting with clergy. As a young scholar who had virtually no training or experience in the art of interviewing, I tried to frame the conversation at the outset.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

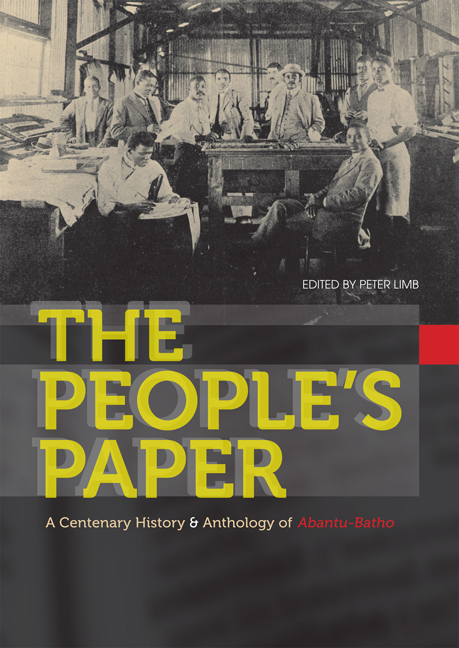

- The People’s PaperA Centenary History & Anthology of Abantu-Batho, pp. x - xiiiPublisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2012